0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

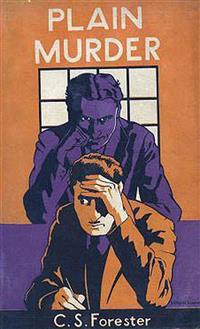

An excellent story, told in style: Three advertising men decide to kill a colleague to avoid dismissal and the grim prospect of joblessness.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Plain Murder

PLAIN MURDER

PLAIN MURDER

books by

C. S. FORESTER

novels

PAYMENT DEFERRED

THE SHADOW OF THE HAWK

BROWN ON RESOLUTION

PLAIN MURDER

DEATH TO THE FRENCH

THE GUN

THE PEACEMAKER

THE AFRICAN QUEEN

THE GENERAL

THE HAPPY RETURN

A SHIP OF THE LINE

FLYING COLOURS

THE EARTHLY PARADISE

THE CAPTAIN FROM CONNECTICUT

THE SHIP

THE COMMODORE

LORD HORNBLOWER

travel

THE VOYAGE OF THE “ANNIE MARBLE”

biography

NELSON

plays

U. 97

NURSE CAVELL

(with C. E. Bechhofer Roberts)

omnibus

CAPTAIN HORNBLOWER, R.N.

miscellaneous

CHAPTER I

THE three young men sat together at a marble-topped table in the teashop. Their cups of coffee stood untasted before them. The saucer under Reddy’s cup was half full of coffee, slopped into it by an irritated waitress who missed the usual familiar smirk which Morris wontedly bestowed upon her when he gave his order. Reddy had not noticed this bad piece of service, although normally it would have curled his fastidious lip. He flicked nervously at the ash of his cigarette and looked across the table at the other two, first Morris with his scowling brow, his woolly hair horrid with grease, his eyelid drooping and his mouth pulled to one side to keep the cigarette smoke out of his eye, and then Oldroyd with his heavy face wrinkled with perplexity.

“He knows about it all right, then,” said Morris bitterly.

“Certain of it,” said Reddy. “I couldn’t have made a mistake. What would he have said that about Hunter for if he didn’t know?”

“It means the sack,” said Oldroyd. “It does that.”

“Tell me something I don’t know,” sneered Morris. “God damn it, of course it does. We know what Mac’s like as well as you do, if not better. The minute he comes back from Glasgow old Harrison’ll go trotting in there, and five minutes after that Mac’s buzzer will go, and Maudie will come and fetch us in to get the key of the street. Mac won’t ever let that by, silly old fool he is, with all his notions about ‘commercial honour’ and stuff like that.”

Morris ended by making a noise in the back of his throat indicating profound disgust; he flung himself back in his chair and filled his lungs deep with cigarette smoke.

“And we’ll be looking for a job,” said Oldroyd. “I’ve been out before and I know what it’s like.”

There was a north-country flavour about his speech: his I’s were softened into Ah’s.

“Know what it’s like? D’you think I don’t know too?” said Morris. “ ‘Dear Sir, In reply to your advertisement in to-day’s “Daily Express” ’—bah, I’ve done hundreds of ’em. God, you’re lucky compared to me. I got a wife an’ two nippers, don’t you forget. An’ a fat chance we’ve got of finding another job. ‘Copies of two recent testimonials.’ What sort of testimonials do you think old Mac’s going to give us? Sacked for taking bribes! We’ll be starving in the streets in a fortnight’s time. Jesus, it’ll be cold. I’ve had some. And all I made out of that damned show was three quid—three measly quid, up to date. Just because that blinking fool, Cooper, couldn’t keep his mouth shut.”

He glowered round at the other two, and so evident was the fiendish bad temper which possessed him that they did not dare remind him of the other factors in the situation which oppressed them with grievances beyond the immediate one of prospective dismissal—they dared not remind him that the whole scheme for extracting bribes from Mr. Cooper was of his devising, nor that they had only shared three pounds between the two of them; their rogue’s agreement gave half the spoils to Morris and divided the other half between Reddy and Oldroyd.

Morris’s rage frightened Reddy even more than did the prospect of dismissal; never having been unemployed, and always having had a father and mother at his back, Reddy did not appreciate fully the gnawing fears which were assaulting the other two—hunger and cold were only words to him. Reddy knew his father would be pained and hurt by his ignominious dismissal, but his mother would stand up for him. It might be long before he could buy himself another new suit; it might even mean giving up his beloved motor-bicycle, although such a catastrophe was too stupendous to be really possible; those were realities which lay in the future, while across the table to him was reality in the present—Morris mad with fury, his thick lips writhing round his cigarette and his thick, hairy hands beating on the table.

That may have been Reddy’s first contact with reality in all his twenty-two years of life, for that matter. He was in touch with emotions and possibilities which he had only read about, inappreciatively, before that. It was strangely fascinating as well as terrifying. Morris had always exercised a certain fascination for him, possibly through the contrast of his virility and coarseness compared with his own frail elegance, but now in the hour of defeat the spell was stronger still. Certainly at the moment Reddy felt no regret at having allowed Morris to seduce them into the manipulation of correspondence which had left a clear field for the tenders of the Adelphi Artistic Studio, and had earned them six pounds in secret commissions and their approaching dismissal.

The blind ferocity in Morris’s face changed suddenly to something more deliberate and calculating.

“By God,” he said, leaning forward and tapping the table, “if we could get Harrison out of this business it’d be all right for us.”

“How do you mean?” asked Oldroyd blankly.

“I don’t know,” said Morris. “But if we could——Get Mac to fire him instead of us, or get him out of the way some other way somehow. One of us would get Harrison’s job then—eight quid a week, and pickings if you kept your eyes open. And we wouldn’t be on the street, either. God! If only we could do it! Can’t one of you two dam’ fools think of anything?”

“No,” replied Oldroyd, after a blank interval of thought, adding, for the sake of his wilting self-respect, “And not so much of your dam’ fools, either.”

“Dam’ fools? Of course we’re all dam’ fools to be in this blasted mess. But we won’t be dam’ fools if we get out of it again. Golly, it would be grand if we could!”

“No,” said Oldroyd heavily, “there isn’t any way out. We’ve just got to take what’s coming to us, haven’t we, Reddy?”

Reddy nodded, but he was not really in agreement. He was still gazing fascinatedly at Morris’s distorted face.

“Don’t be a fool and give up the game before you have to,” expostulated Morris, looking sharply round at Oldroyd. “Mac won’t be back at the office until Wednesday. We’ve still got to-morrow to do something about it. Harrison can’t do anything to us on his own. We’ve still got a chance.”

“Fat lot of chance we’ve got!” said Oldroyd.

The time which had now elapsed since Reddy had first told the story of his interview with Harrison had given him time to recover some of his fatalistic composure; so much of it, in fact, had returned to him that now he was able to turn his attention to the nearly cold coffee before him. He gulped it down noisily and replaced the cup with a clatter on the saucer. Morris sipped at his.

“God! I can’t drink that stuff,” he said, and pushed the cup away.

Reddy did not even taste his. Morris looked up at the clock.

“Look at the time! I’ll have to bunk to get the 6.20. Give us our tickets, please, miss. So long, you fellows. Keep your pecker up, Oldroyd, old man. We’re not dead yet.”

And with that he was gone, forgetting his own exasperation for the moment in the flurry of hurrying out, paying his bill, and scrambling through the traffic in the Strand over to Charing Cross Station. It only returned to him while standing in a packed compartment in the train, crawling along through the first fog of the year; by the time he reached home he was in a bad enough temper to quarrel for the thousandth time with his wife.

CHAPTER II

STANDING in the railway carriage he constituted what a catholic taste might term a fine figure of a man—big and burly in his big overcoat, with plenty of colour in his dark, rather fleshy cheeks. His large nose was a little hooked; his thick lips were red and mobile; his dark eyes were intelligent but sly. The force of his personality was indubitable, he was clearly a man of energy and courage. But no cautious man would say it was an honest face; there was shiftiness to be read there, unscrupulousness, perhaps, and there was in no way any indication of intellect. And at the moment, as it had been when young Reddy had been so impressed, it was marked by every sign of violent bad temper. Nor was that bad temper soothed by the crowded state of the train, nor by the delays caused by the fog. Morris was stimulated to viciousness by the time he reached his station.

He elbowed his way out of the carriage, showing small regard for other people’s toes and other people’s ribs; he forced his way along the crawling queue which was passing through the ticket collector’s gate, and then he crossed the main road and strode in a fury of bad-tempered haste up the tremendously steep hill to his house. It was an incline which would have tested the lungs of a man in good training when taken, as Morris did it, at five and a half miles an hour; Morris, a little too fat and quite out of condition, was gasping by the time he reached the top. That was nothing unusual, however. Morris was nearly always bad-tempered when he was going home, and he usually took that hill too fast in consequence.

At the top he was in the heart of the New Estate, as every one about called it, despite the fact that it was already five years old. From the point of vantage at the top of the hill one could look round and down at hundreds of little houses of white stucco, red roofed, pitiful little places, terraces and crescents and squares; pitiful because they represented an attempt on the part of the County Council to build houses (which could be rented at prices not much too expensive for artisans, without imposing too great a burden on the rates) bearing the hallmarks of advanced civilization at a cost which utterly precluded them. They were semi-detached houses, each couple standing proudly in its own plot of land, but pathetic because if the houses had been big enough to be really habitable they would have filled their particular plots to overflowing. They had casement windows, which were quite pretty, save for the objection that to clean the outside of the hinged window one needed to climb up to it with a ladder from without, for to do it from within called for the services of some one with an arm nine feet long. The boilers were scientifically arranged so that the sitting-room fire heated the water, but by the time three people and their furniture were established in the house there was not an atom of space left in which to store this coal for the sitting-room fire.

Morris had meditated on these facts often enough before, and they had ceased actively to annoy him, but perhaps they contributed to the feeling of irritation which so often urged him up the hill faster than he ought to go. To-night, perhaps, faced with the prospect of dismissal and starvation, he was not so much affected by them. He looked neither to the right nor to the left as he strode up the hill; he swung round at the very summit, for the corner house here, looking out across the Estate and the valley of the Mead clear to London, twelve miles away, was where he lived; had been his home for four years now.

A stride from the front door took him into the middle of the hall. He hung up his hat and coat and another stride took him into the sitting-room.

“Isn’t that kid in bed yet?” was Morris’s way of saying good evening to his wife. “It’s seven o’clock.”

“She’s company for when you come back late like this,” retorted Mrs. Morris. There never was a speech yet to which Mrs. Morris had not a ready and devastating answer. That was one of the reasons of the quarrels between the two.

“Late?” demanded Morris. “Call this late? Only luck I wasn’t a dam’ sight later. Kept at the office, fog on the line, it might have been ten by the time I got here. What’ve you got for my tea?”

“Nice bit of haddock,” said Mrs. Morris, cautiously defensive. Food was a matter of so much interest to her husband that she had always to be ready to defend herself from his charges of feeding him insufficiently or unsuitably.

“Haddock? I’ll have it now. No, put that kid to bed first.”

Molly, his daughter, was kneeling on a chair at the table scribbling on a piece of paper with a pencil. At any moment she might come and ask him to draw a horse for her, or a cat, or an engine. Molly had never learnt that her father had no desire whatever to draw horses for her.

There had once been a time, earlier in their married life, when symptoms of bad temper on her husband’s part had had a subduing effect on his wife, spurring her to haste in obeying his wishes, causing her to walk on tiptoe about the room, to give him soft answers, to be in evident awe of him. But that had passed now. Mary Morris had learnt to “stand up” for herself, as she put it: to counter commands with refusals, anger with defiance. Perhaps this had been partly because she did not love her husband so much now; certainly one cause was that she did not respect him so much now that she knew him better; but the main reason, perhaps, was that a quarrel did at least import some spice of variety into an otherwise drab life.

“No,” said Mary, “let her stay up. She isn’t doing any harm.”

“Seven o’clock is late enough for a kid her age. Bedtime, Molly.”

Molly looked round at him and then went on scribbling. As far back as her memory went there had been no need for instant obedience to one parent when the other was in opposition, and that was the usual state of affairs.

“Did you hear me, Molly?” thundered Morris.

This was a little more serious. Molly looked up to judge her mother’s attitude before she went on scribbling again.

“God bless my soul!” said Morris, turning towards her.

But before he reached her her mother had darted in between them.

“Don’t you touch her,” she said, drawing up her skinny figure undismayed before his overbearing bulk. “Don’t you dare touch her. She’s to go to bed when I say. I’m her mother.”

“Yes, you’re her mother, you——”

The quarrel was well started now, on a familiar opening gambit. It developed on familiar lines; it ended half an hour later in a familiar stalemate, long after Molly had grown tired of scribbling. She had merely climbed down from her chair to play her usual obscure game of houses beneath the table, wherein the footstool represented nor merely the entire household furniture, but visitors and tradesmen and, when necessary, the mistress of the house as well. The quarrel which raged over her head meant entirely nothing to her; it was as familiar a part of her world as was the hearthrug or the sideboard. The quarrel eddied round the sitting-room; it continued with long range indirect fire through the open door when Mrs. Morris went into the kitchen and Morris flung himself into the armchair; it died away when Mrs. Morris’s dropping shots only called forth grunts and wordless noises of disgust from her husband; it seemed over when Mrs. Morris reached below the table, brought Molly out, and started her up the stairs. Thereupon it promptly flared up again when Morris called some jeering remark after her. Mrs. Morris could not possibly leave her husband the last word; she bounced down the stairs again and flung open the sitting-room door. Molly played on the stairs for five minutes before her mother returned and bustled her up to bed.

When Mrs. Morris finally descended she found her husband sitting at the fireside silent and morose. She cooked his supper for him, put it on the table, and said, “It’s ready.” He heaved himself up to the table, ate and drank without a word, and went back in silence to his armchair. He was so subdued and depressed, in fact, that Mrs. Morris credited herself with a victory unusually decisive in the recent argument, and felt a little pleased glow of achievement in consequence, which lasted her all the rest of the evening while she washed up and while she sat mending beside the fire.

Morris sat opposite her, chin in hand. He did not feel any urge that evening to listen to the wireless; he did not want to look again through the morning paper, nor even to put the advertisements in the latter through his usual critical examination. His sanguine temperament had led him to forget his troubles during his argument with his wife, but they returned with new force while she was upstairs putting Molly to bed. When, over his cup of coffee, he had described to Oldroyd so rhetorically the certainty and the unpleasantness of unemployment, he himself had not been so much affected by the prospect he was describing. Fear had been overlain by the irritation caused by the failure of his scheme for raising secret commissions. But fear came into its own now. Morris had no illusions regarding the fate of a city clerk dismissed with disgrace. His throat shut up a little, he felt a difficulty in breathing, as he realized in all its horror the imminence of dismissal, of tramping streets looking for work, of standing elbow to elbow with seedy out of works scanning the “Situations Vacant” columns of the newspapers in the Free Library. He had tasted cold and hunger before, and he shrank with terror, even he, big burly Charlie Morris, from encountering them again. He felt suddenly positively sick with fear. Terror rippled down his skin even while he hunched himself closer to the fire’s comfortable warmth. All men have their secret fear; Morris had discovered his only now that it was too late to save himself by mending his ways. He cursed himself for a fool even while he blanched with fear.

Soon he knew panic; he felt a positive impulse to get up from his chair and run away from these perils which were menacing him. If running away could have saved him he would have run all night through the darkened streets. Morris hitched his chair nearer to the fire instead.

The wailing of his two-year-old son upstairs brought an interval of distraction. John always cried for attention at ten o’clock; his parents had come to look upon it as the signal for bedtime. Mrs. Morris put away her mending and hastened upstairs to him. Morris sat on by the fire for a moment, but habit came to his rescue. He got up from his chair, locked the back door, turned out the gas, passed into the hall, locked the front door, and made his way upstairs to bed.

This mechanical routine, and that following of undressing, had at least the effect of saving him from mad panic. And the chill of the sheets drove every thought from his mind for a time when he got into bed. So it was almost with pleasure that he encountered it—usually his thick body shrank from the cold welcome. He turned on his side; his wife came in and pottered about the room, the shadow of her skinny, half naked figure fell across his face as she passed by him, but he did not open his eyes. Then the light went out and Mary climbed in beside him. The bed lost its chill; Mary turned on her side away from him and lay quiet. He was nearly asleep when the appalling realization of the future surged up again in his mind, and he was instantly broad awake again. Never before had worry kept him awake; the novelty of the experience redoubled its effect. Almost at once the bed seemed to become far too hot. Mary’s body through her nightdress felt positively feverish to his touch as he came into contact with it when he turned in desperation to his other side. Now it was irritation as well as fear which was disturbing him. Why had he been such a cursed fool as to try that stunt for screwing money out of the Adelphi Studio? He might have known that little rat, Cooper, would go straight away and complain to Harrison. God, it was lucky that Campbell hadn’t been there. He’d be on the street now in that case. There was still to-morrow to do something about it.

Desperation now had its effect of driving him into considering action. If only he could think of some way out of the mess! Pleading with Harrison wouldn’t be any use. He knew Harrison. And Campbell too. Campbell was a kindly old soul, but he would not forgive bribery. Every one in the office knew that Campbell had refused a five-thousand-pound agreement with the Elsinore Cork people because they had wanted him to split the commission with them. Poor fool, Campbell. But Campbell was all right. He owned the business. No one could give him the sack, and he drew eight hundred a year out of it. Harrison got six quid a week—eight perhaps. Morris didn’t know. He had wanted Harrison’s job himself—might have got it, later on, if this blasted business hadn’t happened. God, if only something would happen to Harrison—to-morrow. He’d be all right then. But what could happen to Harrison? He might be ill—but he would come back sooner or later. If he were to die—be run over in the Strand to-morrow morning—things would be different. Morris would get his billet then, most likely. Ah, but Harrison wouldn’t be run over. Morris turned irritably over to his other side again as he realized how impossible was the thing he was longing for.

But perhaps it was at that moment that Morris took his first step on the path that lay before him. With Morris to desire something urgently was to start planning how to bring it about. Turning this way and that in the fever-hot bed, his mind working faster and faster but more and more inconclusively, Morris did not notice how often the idea of Harrison’s death came into his mind. A seed of rapid germination was being planted there.

Long after midnight his irritation and his anxiety turned to loneliness and self-pity. He put his hand out to Mary’s thin body. She turned towards him, later, in response to his caresses, and, half asleep, returned with her thin lips the hot kisses Morris thrust upon her with his thick ones. Their arms went about each other in the darkness.

CHAPTER III

THE Universal Advertising Agency in James Street, Strand, would in the eyes of an unsympathetic person hardly have seemed important enough to rouse the emotions which surged so strongly in the breasts of the young men who composed three-quarters of its creative staff. It occupied a first floor office. The reception room which one entered from the main door was furnished lavishly in good reception room taste (for what that recommendation is worth), and the next room, which was Mr. Campbell’s, displayed painstakingly all the latest devices in office equipment which could conceivably find a place in a managing director’s private room. Representatives of big businesses were ushered in here—men possibly with an advertising appropriation of a hundred thousand pounds to dispense—and it was necessary that they (who, ex officio, must know how a business should be run) should be suitably impressed with the efficiency of the Universal Advertising Agency.

But big business never penetrated beyond Mr. Campbell’s office. The next room, wherein were materialized the rosy visions which Mr. Campbell poetically called up before the eyes of big business, was in striking contrast. There was not an armchair, nor a dictaphone, nor a desk of enamelled steel to be seen. Bare boards were all that composed the floor, blotched with ink—Mr. Campbell’s polished parquet and rugs stopped short at the threshold of the communicating door. Most of the space was occupied by half a dozen chipped and battered wooden tables, littered with papers and dog-eared files. Even these tables were allotted to the staff in a manner which displayed no decent attention to the rules of seniority. The centre one of the three under the long window was given over to the staff artist—the long-legged, weedy, lugubrious Mr. Clarence—where he had the best of the light to assist him in his eternal task of lettering and rough sketching. As Mr. Clarence said, his rough sketches might not perhaps be as good as Goya’s finished work, but his lettering was better than any lettering which Sargent had ever exhibited; Goya and Sargent were people for whose work Mr. Clarence had a very sincere admiration—a fact which constitutes a measure of how much Mr. Clarence enjoyed his daily duties of lettering out “Morish Marmalade” and “Sleepwell Mattresses.”

On Mr. Clarence’s right sat Mr. Oldroyd; on his left sat Mr. Reddy. Behind them sat Mr. Morris, but, as has been said, the decent rules of precedence were abruptly interrupted at this point by the fact that beside Mr. Morris was the table of Shepherd, the office boy. Not that Shepherd was much at his table, because most of his time was occupied in journeys to studios, and printing offices, and newspaper offices, arriving everywhere, as Shepherd observed with fifteen-year-old pathos, half an hour late, without gaining his due credit for the fact that anyone not as efficient as Shepherd would have arrived half an hour later still.

Behind Mr. Morris was the seat of power. Symbolically, perhaps, or perhaps so that he could better supervise the work of his juniors, Mr. Harrison’s chair and table were set on a low dais. It was here that the main decisions were reached; it was here that Mr. Harrison held those conferences with representatives from commercial art studios which might result in the launching upon a surfeited world of some new mythical character, some Doctor Healthybody to advise the taking of Perfect Pills perhaps, or Sunray Toilet Soap Girl to declare that Ultra-violet Soap abolishes wrinkles. It was from this dais that Mr. Harrison would step down with fitting solemnity to enter Mr. Campbell’s office to obtain his approval of the final idea.

On this particular morning Mr. Harrison’s frame of mind was peculiarly disturbed. There was no important work to occupy him; a glance at the ruled and dated sheet pinned to his desk assured him that all the advertisements which the office were responsible for sending out that week were either despatched or were in process of final composition on the tables of Morris, or Oldroyd, or Reddy. There were no callers. Mr. Campbell—“Mac,” as Mr. Harrison thought of him—was in Glasgow and not due to return until to-morrow. Mr. Harrison was free to make up his mind as to the action he would take on Mr. Campbell’s return. Mr. Harrison set his lips and stared thoughtfully at the bent backs of his subordinates.

Reddy—his fair hair was illumined by the light from the window—was a good boy, although he had no brains. He would never have thought of the scheme which had been put into practice, which had resulted in the disappearance of the New Commercial Art Company’s suggestions, in the consequent commissioning of the Adelphi Art Studios for a whole series of drawings, and in the payment of six pounds in secret commissions to the three young men before him. Reddy could be excused, perhaps, on the grounds that he had been led astray by the others.