9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

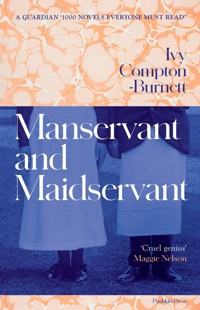

Horace Lamb runs an austere household with tyrannical force and cruel thrift. His five children shiver through the winter and learn that a fire is not a thing to be taken for granted. Hierarchies are more lightly enforced in the servants' quarters, where Bullivant and Mrs Selden attempt to rein in their young charges. When Horace suddenly turns attentive and caring, the real difficulties begin: the taut order of the household slackens, setting loose old grievances.Her own favourite among her novels, Manservant and Maidservant is Ivy Compton-Burnett at her witty, lacerating best. A ruthless satire of power struggles and petty economies, it exposes the violence and cruelty at the core of Victorian family life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

‘Here her wit was at its sharpest, her characterisations most memorable, her dramatic sense at its peak… inexhaustible; each new reading prompts fresh insights’

Penelope Lively, author of Moon Tiger

‘A brilliant novel of the family as tug-of-war, recounted in her hallmark style: repartee we associate today with the plays of Harold Pinter’

Guardian, 1000 Novels Everyone Must Read

‘Dark, hilarious, evil… I have all twenty of her novels and I’ve read nineteen. If I read the one that is left there will be no more Ivy Compton-Burnett for me and I will probably have to die myself’

John Waters

‘Hilarious, harrowing… [like] Jane Austen on bad drugs’

Francine Prose

‘Absolutely sui generis… Her remorseless humor and savagery are a unique cocktail. There’s no middle ground with this novelist—you’re either bewildered by her or you become an addict’

BOMB

‘Each new novel is a fresh shock treatment—individual, complete and stunning’

New York Times Book Review

MANSERVANTand MAIDSERVANT

Ivy Compton-Burnett

PUSHKIN PRESS

Contents

MANSERVANTand MAIDSERVANT

Chapter 1

“Is that fire smoking?” said Horace Lamb.

“Yes, it appears to be, my dear boy.”

“I am not asking what it appears to be doing. I asked if it was smoking.”

“Appearances are not held to be a clue to the truth,” said his cousin. “But we seem to have no other.”

Horace advanced into the room as though his attention were withdrawn from his surroundings.

“Good morning,” he said in a preoccupied tone, that changed as his eyes resumed their direction. “It does seem that the fire is smoking.”

“It is in the stage when smoke is produced. So it is hard to see what it can do.”

“Did you really not understand me?”

“Yes, yes, my dear boy. It is giving out some smoke. We must say that it is.”

Horace put his hands in his pockets, and caused an absent sound to issue from his lips. He was a middle-aged man of ordinary height and build, with thin, wrinkled cheeks, eyes of a clear, cold blue, regular features unevenly set in his face, and a habit of looking aside in apparent abstraction. This was a punishment to people for the nervous exasperation that they produced in him, and must expiate.

“Has that fire been smoking, Bullivant?”

“Well, sir, not to say smoking,” said the butler, recoiling before the phenomenon. “Merely a response to the gusty morning. A periodical spasm in accordance with the wind.”

“Will it put soot all over the room?”

“Only the lightest deposit, sir. Nothing to speak about,” said Bullivant, keeping his eyes from Horace, as he suggested his course.

Bullivant was a larger man than his masters, and had an air of being on a considerable scale in every sense. He had pendulous cheeks, heavy eyelids that followed their direction, solid, thick hands whose movements were deft and swift and precise, a nose that hardly differentiated from its surroundings, and a deeply folded neck and chin with no definite line between them. His small, steady, hazel eyes were fixed on his assistant, and he wore an air of resigned and almost humorous deprecation, that suggested a tendency to catch his masters’ glance.

Mortimer Lamb liked Bullivant; George, his subordinate, disliked and feared him; and Horace merely feared him, except in his moods of nervous abandonment, when he feared nothing and nobody.

George was an ungainly, overgrown youth, whose garb still indicated a state of juvenile usefulness, who shuffled, started and avoided people’s eyes, but managed to present a pleasant appearance, and could not avoid presenting a pathetic one. He made every movement twice under Bullivant’s eye, as though doubling his effort proved his zeal, and the former continued to observe him until he went with a suggestion of flight on some errand to the kitchen. Bullivant relaxed his bearing and turned to Horace almost with a smile, being an adept at suggesting a facial movement without executing it.

“It is to make them do it, sir, not to do it yourself. I should never call doing things myself the harder part.”

“Then why don’t you do them yourself?” said Mortimer, in a reckless manner.

Bullivant turned his eyes on him, and Horace turned his eyes away.

“I cannot understand anyone’s choosing the harder part,” said Mortimer, on a humbler note.

“Well, sir, we have to think of the future, when our own day will be done,” said Bullivant, taking his revenge by including Mortimer in this prospect, and just drawing back before an eddy of smoke.

“I do not have to. I should not dream of doing such a thing.”

“We must not think that the world stops with us, sir, because it stops for us.”

“Bullivant, you did not think I meant you to do things yourself, did you?”

“Does that chimney want sweeping?” said Horace, not pretending to abandon his own line of thought.

“No, sir, not until the spring,” said Bullivant, in a tone of remonstrance.

“Might it be as well to light the fire earlier?” said Mortimer, not looking at his cousin.

“Well, sir, for one morning like this, there may be a dozen with the grate drawing as sweet——” Bullivant broke off before his simile developed, and again recoiled.

“There must be some obstruction in the chimney,” said Horace.

“Well, sir, if that is the case, it is not for want of enjoinder,” said Bullivant, referring to his latest encounter with the sweep, and keeping his face immobile in the face of another gust. “George, ask Mrs. Selden to retard the breakfast. There is a matter that calls for investigation.”

George despatched the errand and returned. Bullivant made a dumb show of his requirements, as though spoken directions would be beneath himself and difficult for George. The latter, after a moment of tense attention, disappeared and returned with a pole, which he proceeded to thrust up the chimney.

“Is the fire too hot?” said Horace.

“No, sir,” said George, with simple truthfulness.

“It seems to lack most of its natural characteristics,” said Mortimer.

Horace kept his eyes on the operations, as if he did not hear. George conducted them with no result, became heated without aid from the fire, and finally glanced at Bullivant. The latter took the pole, gave it an easy, individual twist, and caused a dead bird to fall upon the hearth. George looked as if he were witnessing some sorcery, and Bullivant returned the pole to him without word or glance, but with an admonishing gesture with regard to some soot upon it.

“Well, the grate is not at fault,” said Horace, as if glad to exempt his house from blame.

“The bird is a jackdaw,” said Mortimer. “A large, black bird. Did you put it there, Bullivant?”

Bullivant indicated the bird to George with an air of rebuking omission, and when the latter had borne it away, turned gravely to Mortimer.

“So far am I, sir, from being connected with the presence of the fowl, that I was not confident, when I took matters into my own hands, of any outcome. I merely hoped that my intervention might lead to a result.”

“The mistress is late,” said Horace, “but she prefers us not to wait for her.”

“That is understood, sir,” said Bullivant. “She has spoken to me to the effect.”

He moved to a door and returned with an air of having met the situation. When George reappeared with the dishes, he took them from him and set them on the board, turning the implements for serving to the convenient angle, as though people accustomed to full attendance might not be certain of their use. When Horace had served them, he replaced the covers, and gave the coffee pots a suggestive adjustment.

“The ladies do not mind their breakfast cold,” said Horace.

Bullivant just raised his shoulders over feminine indifference to food, and motioned to George to place a dish by the fire. He kept his eyes on him, as he was intercepted by smoke, to see he gave no signs, and frowned as he gave somewhat dramatic ones.

“So the jackdaw was not responsible,” said Mortimer. “We were too ready to blame what could not defend itself.”

“Yes, sir, I think it was,” said Bullivant, in a low, smooth tone, as though willing to keep the matter between Mortimer and himself. “A proportion of soot has been dislodged, and is having this momentary result.”

“Well, ham is supposed to be smoked,” said Mortimer.

“How do you mean? Supposed to be?” said Horace. “Is it not smoked?”

“Yes, I should think so by now, my dear boy. I meant that a little extra smoking would do no harm.”

“Will you have coffee?” said his cousin.

“Why, is there tea?”

“No, I asked if you would have coffee.”

“Well, I must have it, mustn’t I?”

“How do you mean? Must? There is no compulsion.”

“Of course there is. To have one or the other in the morning.”

“We have given up having our choice, sir,” said Bullivant, in an easy and distinct tone.

“Then you will have coffee?” said Horace.

“Yes, yes, so I must, my dear boy. So I will.”

Bullivant walked on a wide circuit to Mortimer’s place, and set the cup at his hand, meeting his abrupt stirring of it as his natural behaviour.

“I have lived in this house for fifty-four years,” said Mortimer. “Fifty-four years to-day. I was born in eighteen hundred and thirty-eight.”

“Do you mean it is your birthday?” said Horace.

“No, no, not that, my dear boy, nothing like that. Just that I was born in this house fifty-four years ago.”

“Many happy returns of the day,” said Horace.

“May I also offer my congratulations, sir?” said Bullivant, his tone striking a subtle degree of initiative and intimacy.

“Thank you very much. It is unusual to have all one’s experience under one roof. And I have really had none outside it. I cannot imagine anything happening to me anywhere else, or anything happening to me at all. Not that I mean anything; I do not much like things to happen, or I should not much like it. I am content to live in other people’s lives, content not to live at all. Whatever it is, I am content.”

Mortimer Lamb had a short, square figure, a round, full face, rounded, almost blunted features, a mobile, all but merry mouth, and dark, kind, deep-set eyes, that held some humour and little hope. He would have been disappointed not to have a profession, if he had thought of having so expensive a thing. He gave his time to helping Horace on the place, or rather gave part of his time, and did nothing with the rest. His chief emotions were a strong and open feeling for his cousin, and a stronger and necessarily less open feeling for his cousin’s wife.

“I also was born in this village, sir,” said Bullivant, “and have also spent the major part of my life under this roof.”

“And where were you born, George?” said Mortimer.

“In—in the institution—in the workhouse, sir,” said George, with a startled eye, giving Bullivant an almost equal glance, in recognition that the worst had come to pass.

“Well, but in what place?” said Mortimer, as if this were the point of his question.

“At the workhouse in our town, sir.”

“And were you brought up there?” said Mortimer, while Bullivant gave a slight shrug, in acceptance of George’s past being thus in keeping with him.

“Yes, sir, until I was old enough to work.”

“And were you unhappy there? That is, were you happy?”

“No, sir. Yes, sir. Not unhappy,” said George, causing Bullivant’s shoulders to rise again over his finding the experience to his mind.

“So it was not like Oliver Twist?” said Mortimer.

“No, sir, not often, sir,” said George, evidently used to the question. “It was only no home life, sir.”

“And did they teach you there?”

“We went to the local school, sir, with other boys.”

“And was it all right for you there?”

“We were scorned up to a point, sir,” said George, in simple comprehension.

Bullivant glanced at George, but went no further, as though he himself knew where to stop.

“Well, we carry no sign of our history,” said Horace.

Bullivant gave George another glance, feeling this was a point on which opinions might differ.

“You can keep your own counsel,” said Horace. “You owe no one your confidence.”

“I have never sailed under false colours, sir,” said George, causing Bullivant to frown at the needless personal touch.

“What made you think of being a house servant?” said Horace.

“I was put out as houseboy, sir, because a place offered, and then one keeps on with it.”

“Do you regret it?” said Mortimer.

“No—no, sir,” said George, with a glance at Bullivant, who did not countenance belittlement of the calling.

“So you have no home in the neighbourhood?” said Mortimer.

“No, no home at all, sir.”

“He has places to go to, sir,” said Bullivant, in a tone that deprecated exaggerated concern. “The lad has met with kindness. He is on his feet.”

“The ladies are on the stairs,” said Horace, as though the private lives in question at the moment were hardly George’s.

Bullivant pointed sharply to the hearth. George, in concordance with his master’s view, sped to lift the dish and place it on the board. Bullivant himself walked forward and drew out a chair.

“Good morning,” said a rather deep voice, as the mistress of the house entered and took the seat opposite to Horace, something in their way of meeting without words showing them husband and wife. “There is nothing to justify my being late. The morning is no damper and colder for me than for anyone else, though I felt it must be.”

“It was for us it was that,” said Mortimer. “But we were glad to bear it for you.”

“This room is never damp. It could not be in its situation,” said Horace, who saw in his family house the perfection he had not found in his family. “And cold is too strong a word.”

“What word should be used?” said his wife, with her glance about the wide, bleak room coming to rest on the grate.

“A slight contretemps with the fire, ma’am,” said Bullivant in a low tone, bending towards her.

Charlotte Lamb was a short, broad woman of fifty, ungraceful almost to ungainliness. She had iron-grey hair, so wiry that it appeared unkempt, though it was not always so; clothes that were warranted to defy any usage, but hardly did so in her case; a rather full colour, features somewhat poorly formed, and eyes of a strong, deep blue, that showed anger, mirth or emotion as occasion called; and occasion called a good deal.

Horace had married her for her money, hoping to serve his impoverished estate, and she had married him for love, hoping to fulfil herself. The love had gone and the money remained, so that the advantage lay with Horace, if he could have taken so hopeful a view of his life.

Horace had inherited a house and land, and Mortimer had inherited nothing, save an unspoken right to live under the family roof. Horace’s father, who was uncle and guardian to Mortimer, had assured the young men on his deathbed that he left no debts. They had expressed at the moment their appreciation of the inheritance, and had found later that his description of it was just. Mortimer took what money was given him, without even formal gratitude, feeling it enough to harbour no grievance. Horace saw the possession of money with a rigid and awed regard, that in the case of his wife was almost incredulous. That the money belonged to Charlotte rather than to anyone else, was a problem he had never solved, though the solution was simply that she came of a substantial family and was the only surviving child. He laid his hands on the balance of her income, and invested it in his own name, a practice that she viewed with an apparent indifference that was her cover for being unable to prevent it. She had put off remonstrance until it had become unthinkable. Horace held that saving the money, or rather preventing its being spent, was equivalent to earning it, and he pursued his course with a furtive discomfiture that clouded his life, though it could not subdue his nature.

“Has the fire been smoking?” said Charlotte, unconscious of the effect of her words.

“Yes, but not of its own accord. There was a jackdaw in the chimney,” said Mortimer.

“A what?”

“A jackdaw. Bullivant brought it down.”

“How did he know it was there?” said another voice, as an elderly woman entered the room, and paused with an air of humour and weight.

“There was palpably an obstruction, ma’am,” said Bullivant, as he placed a chair.

“Was it a dead jackdaw?”

“Yes, and a stage beyond that,” said Mortimer. “George did what was necessary. I don’t know what it was.”

George paused in readiness to supplement the account.

“No, George, no. Not before the ladies,” said Bullivant, making a gesture with his hand.

“And did the fire stop smoking then?” said Miss Lamb.

“Well, it had formed the habit,” said Mortimer. “It did not break it all at once.”

“Some soot had been dislodged, ma’am, and caused the later ebullition,” said Bullivant.

Emilia Lamb was aunt to Horace and Mortimer, and had also spent her life in the house. She was a tall, large woman of seventy-five, with a marked, individual face, a large, curved mouth, grave, pale eyes, obtrusive hands and feet, and the suggestion of imperfect control of movement, that accompanies unusual size. She was seen as a rare and impressive personality, and as she saw herself as others saw her, had one claim to the quality of rareness.

“It is a very cold day,” said Charlotte, looking again at the grate. “They say there is no smoke without flame, but it does not seem to be true.”

“A jackdaw might lead to the one rather than the other,” said Mortimer.

“Why was it a jackdaw rather than any other bird?” said Emilia, bending her head with her slow smile.

“I don’t think another bird would have done. There was a good deal of smoke. A sparrow would have been no good.”

“Breakfast seems to get later and later,” said Horace, looking at the clock.

“No, it keeps to its time,” said Charlotte. “It is Emilia and I who do that. In the winter eight o’clock might be the middle of the night.”

“Many people get up earlier.”

“Yes, those who do all manner of work.”

“At what time do you rise, Bullivant?” said Mortimer.

“Well, sir, the foundations of the house have to be laid.”

“And you, George?” said Mortimer.

“Well, sir, there is no hardship here, that I did not get used to in the workhouse.”

Horace glanced up in question of this word for George’s experience, and the latter, in relief that his secret was out, moved about rapidly, without encountering anyone’s eye.

“George was born in the town,” said Mortimer. “The workhouse is on the market square. We are all natives of the place.”

But a silence ensued, and Bullivant, feeling that George was unsuitably the cause of it, put something into his hands and motioned to him to withdraw.

“So that was George’s start in life,” said Charlotte.

“Yes, ma’am,” said Bullivant, in a tone in which regret and acquiescence had an equal part.

“I had not heard of it before.”

“No, ma’am. I thought the boy had his feelings about it, and of a nature to be respected. He drew no veil over it with me.”

“I wonder how it has served him as a background for his life,” said Emilia.

“Oh, well, ma’am, it has to serve some people.”

“What happened to his mother?” said Mortimer.

Horace looked a question.

“Well, George had to be born of woman, my dear boy, even in a modern institution.”

Bullivant gave a slight, involuntary sound, and answered as if it had not occurred.

“I have understood that his mother died in his infancy, sir.”

“Poor George!” said Emilia.

“Oh, well, ma’am, he knew nothing better.”

“That is what I mean.”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Bullivant, in submission to her feeling.

“How about the father?” said Mortimer.

Bullivant did not lift his eyes and busied himself with something on the table.

“Well, so much for the parents,” said Mortimer, finding himself speaking for Bullivant’s ears, or rather for the ears of the women as Bullivant regarded them. “The only problems for George concern himself.”

“He would have no problems, sir,” said Bullivant, as though George would hardly be up to these.

“What made you engage him?” said Horace.

“Well, sir, the lad wished to better himself. And I was not averse to a piece of plastic clay. It takes one’s own mould. It is better than having someone who knows everything and can learn nothing. And the first can hardly be said of George.”

“And you find he shapes, do you?”

“Oh, well, sir, shapes!” said Bullivant, lifting his shoulders and then glancing at the women and lowering his voice. “But we have to think of our wages, sir.”

“He takes the rough work off you, doesn’t he?” said Mortimer.

“Well, sir, I give him what chance I can,” said Bullivant, piling some china on a tray and bearing it to the door on one hand, in illustration of his personal standard.

“It is true that George is underpaid,” said Charlotte, “though it is not like Bullivant to refer to it almost aloud. And he has lived down the workhouse stigma by now.”

“We knew nothing about the workhouse,” said Horace.

“Bullivant knew,” said Mortimer, “and kept it in his heart.”

“We cannot ask Bullivant about it,” said Charlotte, “because he is not paid quite enough himself. Of course we do not dare to pay him much too little. We only oppress the weak.”

“From him that hath not, shall be taken away,” said Emilia.

“Not everyone would engage a man of Bullivant’s age,” said Horace. “I remember him in George’s stage when I was a child. He must be years older than I am.”

“His years of service here have put him beyond serving anywhere else,” said Mortimer. “It must happen, if we give it time. The same thing is true of me, though I have not his footing in the house. And talking of time reminds me that to-day is my birthday. If there is any money to spare, Charlotte, do not give it to—to anyone but me.”

Bullivant, whose return had determined this conclusion, resumed his duties without sign of having heard it. This was no indication that he had not done so, but he did not concern himself with the material affairs of the family. Such things, as they managed them, were beyond his range, and so outside his interest. He knew that Mortimer was dependent on his relatives, but did not know the unusual nature of the situation, saw it indeed as another form of private means, and had no idea how it differed from other forms.

“Mrs. Selden is hoping to see you this morning, ma’am,” he said to Emilia.

“I will come to the kitchen at the usual hour.”

“It is good of you to relieve Charlotte of the housekeeping,” said Horace.

“I have done it since the day of your birth and your mother’s death. A habit is formed in that time.”

“There is no time left for me to form it,” said Charlotte. “And I admit the housekeeping does not attract me. It seems so frugal and spare and plain. And if my children are to be unwarmed and poorly fed, it shall not be my arrangement for them.”

“We are all very well,” said Horace.

“But hardship is known to mean that people are never ill.”

“You had a letter that seemed to trouble you, Charlotte. Can I be of any help?”

“My father is feeling his age, and wants me to go and see him. And he lives on the other side of the earth.”

“Does he ask you to pay him a visit?”

“No. He says it is my duty to do so.”

Charlotte’s father had made over money to her, in view of the expense of her family, and his son-in-law could not ignore his claim.

“I could take you, if both of us could leave the children.”

“It is I who cannot do that, and I who shall have to. That is the beginning and the end.”

“We will all do our best,” said Emilia, who had heard with grave eyes. “But the news is not good.”

“Bullivant, are you going to be all day, lifting that cloth off the table?” said Horace.

Bullivant took up the cloth by the corners to preclude the escape of crumbs, and bore it to the door, his manner acquiescing in the occasional propriety of his absence.

“We must not think Bullivant has no sense of hearing,” said Horace.

“I thought you did think so,” said Mortimer. “But he will not accuse you of it on this occasion.”

“He has so much, that it is no good to reckon with it,” said Charlotte.

“Now I do not know why I should be belittled and left out of account, as if I were a nonentity in my own house,” said Horace, taking enough advantage of Bullivant’s absence to explain his desire for it. “What children have a better father? Do I ever forget them for a day? Do I ever spend time or money on myself? Do I ever think of the life I could lead, if I had no family?”

“Why could not Bullivant tell you, my dear boy?” said Mortimer. “Why should he be the one to go?”

“Why should I not be granted the position that is mine?”

“It is assumed that it goes without saying,” said Emilia.

“That is a dangerous line to take. You might estrange anyone by acting on it.”

“Why, so we might,” said Mortimer. “So it appears we have.”

“What is my life but sacrifice of myself?”

“What is anyone’s life?” said Charlotte. “We all owe so much to each other, that no life can be anything else.”

Horace fixed his eyes on her face with a conscious, questioning look that repelled and angered her.

“A woman is not the creature that cannot bear to be stared at,” she said.

As Horace withdrew his eyes, they happened to fall on the grate, and he was carried away on a more instinctive emotion.

“Now how often have I forbidden this piling up of a fire, that is to be of no use until the afternoon? I have said it and said it until I am weary of the words. What a waste of fuel that might be of use to somebody! What a coarse and common thing to do! It savours of ostentation, of display for its own sake. I could not have believed that anyone in this house would stoop so low. Now who was it who did the thing? It must have been somebody.”

“Why, so it must,” said Mortimer. “You might have thought of that.”

“It was Bullivant,” said Emilia, keeping her mouth grave.

Horace walked to the bell and stood with his hand upon it, and withdrew it only as steps approached the door.

“Who made up the fire, Bullivant?”

“Either George or myself, sir.”

“But which of you?”

“Well, there were various dealings with it this morning, sir. I could not definitely say who was the last to be in contact.”

“You were seen to make it up,” said Horace, in a deepening tone. “Miss Emilia can bear witness to it.”

“Then it was I, sir,” said Bullivant, turning to Emilia with a slight bow, in acknowledgement of her aid to the position.

“But what possessed you to go counter to my wishes? Have you not heard me say a hundred times that this fire is to be low in the morning? What moved you to build up this great, showy pile?” Horace, who had removed some coal from the grate, restored it to show its previous condition.

“Well, sir, the ladies remarked upon the cold, and I felt I had perhaps overstressed economy in postponing the putting of the match until so late. And I hoped by some extra attention to redress the balance.”

“I thought you did not remember making it up.”

“It has been recalled to me, sir,” said Bullivant, with another bow towards Emilia, who would have felt inclined to return it, if she could have accepted his view that she had served him.

“But there was no need to overdo things like this.”

“No, sir, overdo is perhaps the word. But there were matters to contend with in various shapes this morning.”

“And one of them took the shape of a jackdaw,” said Emilia, with a smile, but disappointed of an answering one from Bullivant.

“See that it does not occur again,” said Horace.

“No, sir, the circumstances would hardly repeat themselves,” said Bullivant, in an acquiescent tone, as he went to the door.

“You informed against your aunt, my dear boy,” said Mortimer. “And she informed against Bullivant. He comes out better than either of you.”

“Oh, he was going to blame it all on to George, a helpless orphan from the workhouse,” said Horace. “There is not much to choose between us.”

“It was a bad hour for George, when he told the truth about himself,” said Mortimer. “It was sad to see him thinking that honesty was the best policy.”

“Well, he cannot learn too soon that it is not,” said Charlotte. “He should leave the workhouse training behind.”

“Honesty does not involve a complete lack of reticence,” said Horace.

“George thinks that is what it does,” said Emilia.

“There are things he could reasonably keep to himself.”

“He was asked a question and answered it truthfully,” said Mortimer. “We know we should not ask questions, but the reasons given are wrong. I asked him where he was born.”

“Why did you want to know?” said Horace.

“I don’t know, my dear boy; I don’t think I did want to. But Bullivant had told us where he was born, and I had told people where I was; I don’t know if they wanted to know. So when George did not tell us, I asked him. I think it was just to include him as a fellow creature. And then the poor lad had to confess that he was not one. It was sad to see him thinking how much credit the confession did him.”

“I wonder who began this treating of people as fellow creatures,” said Charlotte. “It is never a success.”

“Once begun, it is a difficult thing to give up,” said Emilia.

“We shall lose interest in it, when the novelty wears off,” said Mortimer. “It seemed such an original idea.”

“We can see how unnatural it is, by what comes of it,” said Charlotte.

“I wonder if George regards us as fellow creatures,” said Emilia.

“I believe he does,” said Mortimer. “But I do not think Bullivant would approve of it.”

“Are you really thinking of leaving us, Charlotte?” said Horace.

“I am thinking of visiting my father, which will involve my doing so.”

“And we can do nothing,” said Mortimer. “Only count the hours to your return.”

“That will hardly be of help to her,” said Horace.

“I think it will be a little help, my dear boy. It is nice to be missed.”

“We had better not tell the children until just before she goes,” said Emilia.

“They should face the truth,” said Horace. “It is a sounder preparation for the future.”

“We can never prepare for that,” said his wife. “We know too little of it. And facing things is not a good habit; it causes needless suffering.”

“Coming events very seldom cast their shadows before them,” said Emilia. “But in this case we see the event itself. Perhaps they should be told while it is still ahead. Then they will be spared the shock.”

“Of course that is how it is,” said Horace, as if this had been his thought all the while.

“It was not the account you gave,” said Charlotte.

“Well, no, it was not, my dear boy,” said Mortimer.

Horace rose and left the room in an abstracted manner, and Emilia glanced at the other pair and followed.

“So you are deserting me, Charlotte,” said Mortimer.

“I am deserting the children and am thankful to leave you with them.”

“I will serve them because they are yours. But I wish I were your child.”

“I do not wish it. I have enough children. I often wonder how much harm I have done. Would it be better for them, if they had not been born?”

“The change for them is coming. Your return must be our sign. If we hesitate longer, we shall lose our time and theirs. We must break from Horace and live apart and at peace. We will marry, if he makes it possible. It will be easier for him after this break in his life; the parting will smooth the way. How we find ourselves considering him! Is it a sign of some nobility in us?”

“Not unless there is a touch of nobility in every human creature, as I have heard it said.”

“Is there something in Horace that twines itself about the heart? Perhaps it is his being his own worst enemy. That seems to be thought an appealing attribute.”

“The trouble with those who have it,” said Charlotte, “is that they are bad enemies to other people, even if not the worst.”

“Will he be able to remain in this house, without your income?”

“He can live in a corner of it, with Cook and Bullivant.”

“That will bring back his early days. And of course home is where Bullivant is. But still, the poor boy! A poor thing but mine own.”

Bullivant returned to the kitchen and to conversation with the cook. The latter was engaged in supervising her underling, a work in which she and Bullivant were equally versed.

“Fire too large, Mrs. Selden,” he said, taking a seat with a view of George in the distance, in order to maintain this usefulness. “And the master as heated as the fire, if you ask my opinion.”

“As seems to increase in frequency,” said Cook. “Was it you or George?”

“Myself, as I freely admitted, Mrs. Selden.”

Mrs. Selden was really Miss Selden, but Bullivant followed the address of the cook observed in formal house holds, deprecating the modest fashion of basing it on her calling. George did the same, whether by reason of precept or example was not known. Cook showed indifference on the matter, and thereby showed her dignity as dependent on itself.

“More can be asked of no one than admitting it,” she said. “It is at once the most and the least that can be done. Miriam, are you attending to your work or listening to me?”

Miriam, who was doing the latter, gave the start she was accustomed to give when addressed, and proved the bracing effect of the words by proceeding to do both.

“It emerged about George and the workhouse this morning,” said Bullivant, lifting one knee over the other. “All of it out in the open! And where was the need? It had better have remained where I had consigned it, in oblivion.”

“How did it transpire?” said Cook.

“There was talk about our places of birth, and we all made our contribution,” said Bullivant, with a note of complacence. “The master and Mr. Mortimer and I had spent the major part of our lives under this roof. With George, as we know, it has been otherwise.”

“And what was made of it?”

“Nothing much on the surface, Mrs. Selden. But I suspect there was consternation beneath. But, as I hinted to the master, wages such as ours can hardly preclude slurs of the venial kind.”

“And how did George bear himself under the ordeal?”

“As well as could be asked of him,” said Bullivant, craning his neck as the name recalled its possessor. “They were not circumstances calculated to bring out any latent advantage in him, if such there be. But he was equal to owning the truth.”

“It is to his credit that he did not have recourse to invention.”

“Well, Mrs. Selden, the boy would hardly have it in him.”

“Miriam, are you working this morning or observing an occasion of leisure?” said Cook.

Miriam started and resumed her employment.

“I suppose all this about George is highly interesting to you,” said Cook, with a note of belittlement that Miriam could not explain.

“The world is new to you, is it not, Miriam?” said Bullivant.

Miriam remained transfixed for a moment, her habit when addressed by Bullivant. She was a stolid-looking girl of sixteen, on whom the plumpness incident to this age had fallen in excessive measure. She had a round, red face, large, startled eyes, round, red arms, a mouth that, as it was generally open, may also be described as round and red, and a nose that must be described in this manner. Mortimer had met her on the stairs and asked if she enjoyed her life, and had not suspected that her reply that she did not know, was a true one. She had no standard by which to form her judgement. Cook showed her no unkindness, and Bullivant was almost kind, though he would hardly have noticed if she had appeared with another face, and had no idea how much she would have liked to do this. Cook acted towards her as her conscience dictated, and Bullivant felt that she was female and was not George.

Two housemaids, whose duties lay upstairs, completed the household, and seemed to have little to do with the others, as they accepted no dealings with George and Miriam, and were permitted none with Bullivant and Cook.

“Are you a native of this district, Mrs. Selden?” said Bullivant, with courteous interest.

“Well, I was born in the county, though in a part that would make this section look very bare. It was on the more luxuriant side.”

“And you, Miriam?” said Bullivant, after a moment of humming with some tunefulness.

Miriam did not reply.

“Did your family live about here?” said Cook, translating for her benefit.

“I don’t know,” said Miriam.

“Did they know?” said Bullivant, smiling.

“You must know where you were born,” said Cook.

“No. I was six months old when they took me.”

“When who took you?”

“The orphanage. They could tell I was about that.”

“The orphanage beyond the town?” said Bullivant.

“Did you not know she had passed her life under those conditions?” said Cook. “Something of that nature seems to emerge?”

“Dear me, so we are all natives of the district,” said Bullivant, who had an example to guide him in the circumstances.

“Surely they told you as much as where you were born,” said Cook, who was without this advantage.

“No, I was found.”

“On a doorstep?” said Bullivant.

“Yes,” said Miriam.

“On a doorstep where?” said Cook.

“The orphanage,” said Miriam, looking surprised by the idea that there might have been a choice of such resting-place.

“But your parents must have given you your name.”

“No. It was the name of the baby who died, the one whose place I took.”

“Dear, dear, a sad little tale,” said Bullivant, on a musical note.

“Well, the name does as well as any other,” said Cook. “What is your other name?”

“She can’t have one clearly, Mrs. Selden,” said Bullivant, in a lower voice.

“Yes, I have. It is Biggs, the baby’s name,” said Miriam.

“Miriam Biggs,” said Bullivant, as if he hardly congratulated the baby. “Well, I expect you like your first name, do you not?”

“No.”

“And why do you not like it?” said Bullivant, who had felt it was rather above its bearer. “What kind of name do you like?”

“A name like Rose,” said Miriam, with a sort of glow in her voice.

“Well, perhaps you would like to be called a lily as well,” said Cook.

Miriam’s eyes showed that this was the case.

“What resemblance do you bear to either of these blossoms?” said Cook, causing a slight, sensitive recoil in Bullivant.

Miriam had not words to explain that she would appreciate a single point in common.

Cook, recalled to the matter of appearance, stepped to a glass to smooth her hair, and glanced at her tight, shiny forehead, the nose that rose towards it, her sallow complexion and clear, shrewd, grey eyes, with the encouraged air that tends to result from such a survey, as though people are relieved to find no feature as yet missing.

A look that can only be described as roguish, flitted over Bullivant’s face. It occurred to him to ask Mrs. Selden what blossom she resembled, but he was deterred by propriety and a regard for their future relation, if not by the consideration that he resembled no blossom himself.

“You were well and happy at the orphanage, Miriam?” he said.

“I am always well,” said Miriam, on a rather unexpected note.

“And do you not like that?”

“No, not much.”

“And what is your reason for desiring poor health?” said Cook.

“I have never had an illness,” said Miriam, on a wistful note.

“Well, let me tell you that it is not an object for aspiration,” said Cook, in a tone of some personal affront. “I have been laid prostrate more often than most, and am in a position to testify.”

“I should like to have a real illness. It seems as if it might pull me down and make me different.”

“But your recovery would build you up again,” said Bullivant, as if the question of stoutness or the opposite were a light one.

“I presume that you would not wish your indisposition to become a chronic state,” said Cook. “I should never call my recovery, even from the most lenient of my onsets, complete. And it adds to what has to be contended with.”

“And we are none of us the worse for a covering on our bones,” said Bullivant.

“We can’t all belong to the lean kine,” said Cook, veiling by the phrase her pride in being of these.

“Do not aspire to be ill until you must, Miriam,” said Bullivant.

“And some constitutions do not tend to illness,” said Cook, almost in a tone of threat. “They are not susceptible.”

Miriam could not dispute this.

“And I like to see a good, wholesome girl,” said Bullivant, bringing no comfort to Miriam, who had been told before that she gave people this pleasure, and had found it increased their demands of her rather than their opinion.

“What an amount of charity origin there is in the house!” said Cook. “It is my first contact with it. My family looked down on no one, but we had our bounds.”

“Our wages, Mrs. Selden, our wages,” said Bullivant, in a low tone that seemed designed to elude the ears of Miriam, and did elude her attention.

“Well, they did not teach you much at the orphanage,” said Cook, surveying the latter’s handiwork.

“We learned from books until we were sixteen,” said Miriam, in an explanatory tone.

“And were you a promising scholar?” said Bullivant.

“In which case the promise has hardly led further,” said Cook.

“No, I didn’t get on,” said Miriam, in a tone of assent.

“Now you know the next thing to be done, after the times you have been told,” said Cook.

Miriam knew, as the result of this method, and left the room to accomplish it.

“I always say that not the least thing I have done, is the number of girls I have trained,” said Cook.

“I say the same, Mrs. Selden, both of you and of myself.”

“Boys are not the same demand.”

Bullivant shook his head and rose, under the necessity of acting on the opposite assumption. He did not pursue George with success, for the latter presently edged round the door, saw Cook by herself, and looked round to assure himself that his eyes had not deceived him. Then he betrayed the turmoil of his spirit by taking Bullivant’s chair, while Cook looked on with an equivocal eye but without prejudice. She could always feel that George was male and was not Miriam.

“My secret is out, Mrs. Selden.”

“Well, as long as you had no recourse to deception, you have no reason to bow the head.”

“There was one that spoke to me like a father, and that was Mr. Mortimer.”

“I always said a heart beat under that exterior.”

“But I did not like the master’s eye.”

“The eye may be colder than the heart,” said Cook.

“This will always stand in my way, Mrs. Selden. It will prevent my advance.”

“It might tend to militate against it. But you are leaving it behind,” said Cook, who supposed that George was satisfied with his progress.

“People are fortunate to be born into a respected place.”

“I admit that my family would eat bread for respect,” said Cook.

“I could feel to you as to a mother, Mrs. Selden,” said George, on an impulse.

“Then behave to me as a son and hand me those forks,” said Cook, regarding this as the right way to meet excess of feeling. “What with Mr. Mortimer your father, and me your mother, your orphan days are numbered, as far as I can see. And an ill-assorted pair Mr. Mortimer and I should be, as regards worldly station, if not in other points. It was an arbitrary combination.”

There was a pleasure in Cook’s tone, for which George could hardly claim the credit. He was spared the demand of the situation by the entrance of Bullivant, who fixed on him eyes of concentrated feeling.

“Are you the mistress or Miss Emilia, George, that you elect to spend your morning in an easy chair?”

George rose and sped to the fulfilment of his own character, and Bullivant succeeded to the chair, without specifying which of these ladies he personified.

George gained an adjoining scullery, where Miriam was employed at the sink.

“Now get along with your business and leave the place clear for something better. And don’t let me have to tell you twice, because I don’t speak a second time to such as you.”

Miriam recognised an enjoinder to haste, and slightly accelerated her movements.

“And don’t be all day getting hold of what I say,” said George, continuing to prove he was right in regretting his origin, “because I have other things to do, and higher people to listen to me.”

Miriam took this speech to repeat the first, and paid it no heed.

“Whom am I to understand that you are addressing, George?” said a voice from the door, where Bullivant stood with his head thrown backward, so that he seemed to look down on his hearers.

“Miriam,” said George, with a note of triumph, supposing that Bullivant assumed him to be addressing some other person.

“And when have you heard the master or Mr. Mortimer address a woman in that manner?”

George cast his mind over his employers’ deportment, and waited for more enlightening words.

“Miriam,” said Bullivant, in a distinct tone, “will you have the goodness to be as expeditious as possible, in order that George may succeed you at the sink? There are matters requiring his attention, when those that claim your own, are disposed of. I am much obliged to you, Miriam.”

There was a pause while Miriam recognised the same injunction in these words as she had in George’s.

“May I never again, George, be called upon to witness such an exhibition of unmanliness. A woman of whatever standing is always a woman, as the dealings of the master and Mr. Mortimer would prove. There are things that stamp a man as unworthy of the name, and no one of us, of whatever origin, need emerge as that. I will leave you to mention your regret to Miriam.”

Bullivant retraced his steps; Miriam resumed her work; George stood in silence broken by no contrite word.

“I have finished now,” said Miriam, in her usual tones, disregarding an interlude that stood apart from life. “You can have my place.”

George took it and found himself framing with his lips some words that he did not utter: “I am much obliged to you, Miriam.”

Miriam stood doing nothing, her natural state when she was not urged to modify it, and George was seized by one of his sudden impulses.

“I shall always be rough, Miriam.”

“Well, a good deal of the work to be done is rough,” said Miriam, feeling that George had his place in the scheme of things.

“I should like to rise above it.”

“There would be nobody to do it, if everyone rose,” said Miriam, who was more articulate with her equals, and saw George as among these.

“But he who does high things, has people as much indebted to him, as he who does low ones. Wouldn’t you like to rise?”

“No, not very much,” said Miriam, who saw the height of her calling as exemplified in Cook.

“You might rise by marriage,” said George, seeking some means of elevation that had no personal basis.