18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

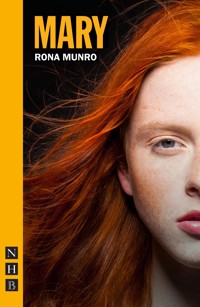

'She made some very poor decisions. You tried to warn her. You love her yet, and that's a credit to you, but you need to think about what's best for Scotland...' It's 1567. James Melville is an intelligent, charismatic and skilled diplomat – and also one of the most loyal servants of Mary Stuart, the troubled Queen of Scots. It's a time of political turmoil, and the shocking crimes he has witnessed have shaken him. Now he needs to decide who's guilty, who's innocent, and who is too dangerous to accuse. Change is coming, but at what price? Mary is an explosive political thriller, and part of Rona Munro's breathtaking theatrical exploration of Scottish history. It is the sixth instalment of The James Plays Cycle which began with James I, II and III, performed by National Theatre of Scotland, including a run at the National Theatre in London, and which won the Evening Standard and Writers' Guild of Great Britain Awards in 2014, and James IV, co-produced by Raw Material and Capital Theatres in association with National Theatre of Scotland, in 2022. Mary received its world premiere at Hampstead Theatre, London, also in 2022, directed by Roxana Silbert.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Rona Munro

MARY

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Original Production Details

Author’s Note by Rona Munro

Mary

About the Producer

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Mary was first performed at Hampstead Theatre, London, on 31 October 2022, with the following cast:

JAMES MELVILLE

Douglas Henshall

AGNES

Rona Morison

THOMPSON

Brian Vernel

Director

Roxana Silbert

Designer

Ashley Martin-Davis

Lighting

Matt Haskins

Composer and Sound

Nick Powell

Movement

Ayse Tashkiran

Casting

Helena Palmer CDG

Assistant Director

Marlie Haco

Author’s Note

Rona Munro

This play, Mary, is the sixth instalment in the cycle of plays I’ve written about the medieval Stuart monarchs of Scotland: The James Plays. At the time of writing this introduction, the fourth instalment, James IV: The Queen of the Fight, has just started a Scottish tour, produced by Raw Material and Capital Theatres. The next instalment, chronologically, would cover the reign of James V, but while that play (Katherine) is now completed, Mary was written first and has already found a production, at Hampstead Theatre.

The reason this story was more urgently in my imagination was that I had already, years ago, done extensive research into the stories of the reign of Mary Queen of Scots. I already had a strong and, I’d claim, well-informed opinion about the events at the end of her reign. It’s not an opinion all historians share but, if you sift through original sources and eyewitness accounts of the time, I struggle to see how you can draw any other conclusion. I think Mary Queen of Scots was raped by James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, to force her into a marriage that briefly gave him power but ultimately destroyed them both.

What happened between Mary and Bothwell is a story that has, I think, great contemporary resonance. Women’s narratives have often been twisted to serve other interests and destroy their true experience. History gaslights women because, until very recently, history was written by men. At the time what happened to Mary was spun as a story of unwise lust and passion, a love story between Mary and Bothwell that confirmed she was unfit to rule. It’s easy to see why it was spun that way in 1567, as it very much served the interest of those grabbing for power. What’s less forgivable, to me, is how some later historians have bought into that version of events without re-examining them with empathy and with the greater cultural understanding we now have on the nature of consent.

There are probably thousands of versions of Mary’s story and everyone, including me, has used her as a vivid vehicle for their own favoured narrative. The story of how powerful women, or indeed any woman, can be manipulated, abused, and terrorised by sexual violence has been told many times, and should be told many more. However, there’s another story I don’t feel I’ve seen so often, the story of why decent, caring, moral men – the majority of the male population, I’d say – still tolerate and enable that violence. James Melville was, I think, such a man. I believe he did love Mary, but he allowed the events we see in the play. I wanted to try to tell the story of that moral journey. For me, that has the greatest contemporary resonance. What Mary faced is not nearly as different from what any woman might face now as we might like to imagine.

I used Melville’s memoirs to get a sense of his character and to tell the story, in its details, as he tells it. However, the character of Melville in the play amalgamates the experience of other men who were originally loyal companions to Mary, and I’ve used other eyewitness accounts to provide the details of the narrative.

Agnes and Thompson, the two other characters in the play, are fictional. However, their goals and attitudes reflect two contrasting interest groups in Scotland at this time of upheaval: one that is quite hard-line, informed by the potential of the religious revolution; one which is more pragmatic, and about maintaining power for the men who already have it.

What happened to Mary, though unarguably rape, in my opinion, may not have been as brutal as I describe, but Bothwell’s assault was witnessed – and what I describe reflects what happened to her, over and over, in all imaginations after that assault was made public.

Whatever your opinion on the necessity of reform of the Church in Scotland at this time, or whatever egalitarian good we can claim from that Reformation, it came at this price.

I don’t ever presume to have answers, only relevant questions, but I do think that cost bears examination.

There is a poem I wrote to be used in the first production. It tries to echo songs we know existed at the time: apparently sweet, melodic ballads that were actually vicious slanders aimed at Mary. A mermaid was another word for a whore. Earl Bothwell’s family crest carried a hare. So this song, ‘The Mermaid and the Hare’, carries that subtext. Its use is optional in any production but included for interest.

The hare rins oer the bonny green,

Tae spy the siller sea,

The mermaid stands ahint the wave –

‘Cam oer the strand tae me.’

‘I cannae swim yon siller sea,

Nor you walk oer the green.’

But she has rin frae sea tae strand –

A hare micht wed a queen.

Glossary of Scots Words

Siller – silver

Ahint – behind

Strand – beach

Rin – run

Mich – might

Characters

JAMES MELVILLE, a courtier and officer of Scottish Government, mid-thirties to mid-fifties

THOMPSON, a servant of court and government, mid-twenties

AGNES, a servant of the royal household, mid-twenties

This ebook was created before the end of rehearsals and so may differ slightly from the play as performed.