5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Old Street Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

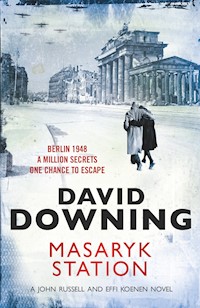

THE HEART-STOPPING FINAL INSTALMENT OF THE BESTSELLING STATION SERIES Europe, 1948. The continent is once again divided: into the Soviet-controlled East, and the US-dominated West. John Russell and his old comrade-in-espionage Shchepkin need to find a way out of the dangerous, morally murky world they have both inhabited for far too long. But they can't just walk away: if they want to escape with their lives, they must uncover a secret so damaging that they can buy their safety with silence. In this dazzling conclusion to the series, Downing ratchets up the suspense with a superb plot involving psychopathic mass murderers, a snuff movie that leads to the highest ranks of Soviet power, and Russell and his girlfriend Effi's last-ditch attempt to gain freedom.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR DAVID DOWNING

‘Outstanding’Publishers Weekly on Lehrter Station

‘Think Robert Harris and Fatherland mixed with a dash of Le Carré’ Sue Baker, Publishing News

‘A wonderfully drawn spy novel … A very auspicious début, with more to come’The Bookseller on Zoo Station

‘Excellent and evocative … Downing’s strength is his fleshing out of the tense and often dangerous nature of everyday life in a totalitarian state’The Times on Silesian Station

‘Exciting and frightening all at once … It’s got everything going for it’ Julie Walters

‘One of the brightest lights in the shadowy world of historical spy fiction’Birmingham Post

‘An outstanding thriller … This series is a quite remarkable achievement’Shots magazine

For Sacha

Abbreviations

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Abbreviations

February 11, 1948

Crusaders

A Walk Into The Future

Stefan Utermann

Sasa

Bearers of light

Merzhanov

Janica

Mordechai’s advice

Sacrificial wolf

Historical addendum

Series acknowledgements

About the Author

Also By David Downing

Copyright

February 11, 1948

They were on their way to bed when the two Russians arrived, but the lateness of the hour was apparently irrelevant: she and her sister were to come at once. She asked if they knew who she was, but of course they did. Refusal wasn’t an option.

Their destination was also secret. ‘Very nice house,’ the one with some German told them, as if that might make all the difference. He even helped her into the fur coat. Nina looked terribly scared, but the best she could do was squeeze her younger sister’s hand as they sat in the back of the gleaming Audi.

Soon the car was purring its way eastward along a dimly-lit and mostly empty Frankfurter Allee. The men in the front exchanged an occasional word in Russian, but were mostly silent.

Like thousands of others she’d been raped in 1945, but only on the one occasion. The three soldiers had been too excited by her house and possessions to do more than satisfy their immediate lust.

And now, she feared, it was going to happen again. In a ‘very nice house’.

She could feel her sister quivering beside her. Nina had only been twelve in 1945, tall for her age, but luckily still with the chest and hips of a child, and so the soldiers had left her alone. She had blossomed since, but was still a virgin. This was going to be so much harder for her.

They were leaving the city behind, driving through snow-covered fields. Three years after the war, the road signs caught in the headlamp beams bore Cyrillic script, and she had only the vaguest idea where they were. Not that it mattered.

They turned off the road up a tree-lined drive, and swung to a halt before a large three-storey house. There were soldiers on guard either side of the door, and another inside who gave them both a curious look. There was only one man in civilian clothes and he had a classic Russian face. This was an enemy camp, she thought. There wouldn’t be anyone there to whom they could appeal.

They were hustled upstairs and down a richly-carpeted corridor to a door at its end. One of their escorts tapped on it lightly with his knuckles, then responded to words from within by pushing it open and ushering them inside.

It was a large room, with several armchairs and a large four-poster bed. A fire was burning in the grate, and several electric lamps were glowing behind their shades, although the light was far from bright. She had never been in a brothel, but she imagined the better ones looked like this.

And then she saw who it was, and her heart and stomach plummeted.

He was wearing a dressing-gown, and probably nothing else. The smile on his face was only for himself.

After calmly locking the door, he walked to a table holding several bottles, poured himself a tumblerful of clear liquid, and gulped half of it down. As he turned back to them the fire briefly glinted in his spectacles.

‘Zieh dich aus,’ he said. Take off your clothes.

‘No,’ Nina almost whispered.

‘We must do as he says,’ she told her sister.

Nina stared back at her. There was fear in her eyes, and pleading, and sheer disbelief.

‘Take me,’ she begged him. ‘She’s only a girl, take me.’

If he understood her – and she thought he did – all it did was increase his impatience.

They slowly stripped to their underwear, pausing at that point without much hope.

He gestured for them to continue, and then stared at their naked bodies. She watched his growing erection strain at the dressing gown, then finally break free. Nina’s gasp made him smile. He took two steps forward, grabbed her wrist, and tugged her towards the bed.

Nina jerked herself free and ran for the door, which rattled loudly but resisted her attempt to pull it off its hinges. As he crossed the room in pursuit, she tried to block his way, but he grabbed her by the arm and casually threw her aside.

Nina grabbed a convenient ashtray, and hurled it in his direction. She didn’t see where it struck him, but the grunt of pain as he doubled over left little room for doubt.

For a few brief seconds the world stood still.

Then he gingerly walked to his desk, and took a gun from the drawer.

‘No,’ she screamed, scrambling towards him.

He lashed out with the barrel, catching her across the cheek as it knocked her to the carpet.

Nina had sunk to her knees, and now he stood before her, his penis dangling in front of her face. He lifted her hair with the gun, and slowly moved around her, his erection returning.

She thought he would force the sobbing girl to take him in her mouth, but what could she do to step in that wouldn’t make things worse?

And then he had the barrel of the gun in the nape of Nina’s neck, and his finger was pulling the trigger. There was no explosion, just a coughing sound, an almost derisory spurt of blood, a silent Nina crumpling on to the carpet.

She tried to speak, to rise from the floor, but both were beyond her.

He came across the room, gun in hand. Expecting to die, she felt almost disoriented when he pulled her up by her hair, and threw her face down on the bed. There was cold metal in the back of her neck, but his hands were wrenching her legs apart, and she knew there was one last thing to endure before she joined her sister.

And then he was ramming himself inside her, urgently pumping away. It only lasted a few seconds, and once he was out again, she lay there waiting for an end to it all, for the blackness the bullet would bring.

It didn’t come. After several moments his hands reached down for one of hers, and cradled it around the butt of the pistol. At first she didn’t resist, and by the time she realised the implication, he had taken it back again.

‘You’re too famous to kill,’ he said in explanation.

Crusaders

The Russian was almost certainly lying, but John Russell had no intention of sharing this suspicion with his British and American employers. If there was one thing he’d learnt over the last few years, it was never to divulge any information without first thoroughly assessing how much it might be worth in money, or favours, or blood.

The British major and American captain who shared command of the Trieste interrogation centre seemed less inclined to doubt the Russian. A kind reading of the situation might have them lacking Russell’s suspicious nature, although one would have thought that a necessary qualification for intelligence officers. Being about half Russell’s age and coming from two different realms of Anglo-American privilege, they certainly lacked his experience of European intrigue. But a third explanation for their naivety – that both were essentially idiots – seemed by far the most likely.

The Brit’s name was Alex Farquhar-Smith, and Russell would have bet money on a rural pile, minor public school, and Oxford. At the latter he had probably spent more time rowing than reading, and only been saved from a poor Third by a timely world war. The Yank, Buzz Dempsey, was a Chicago boy with a haircut to suit his name, and a brashness only slightly less annoying than his English colleague’s emotional constipation. Usually they spent most of their working hours getting up each other’s noses, but today they were both too excited.

The source of their exhilaration was the tall, rather elegant, chain-smoking Soviet major sitting on the other side of the table. ‘I have some information about the Red Army’s battle order in Hungary,’ Petr Kuznakov had casually mentioned on arriving in Trieste the previous day, as if unaware that such intelligence was the current holy grail of every American and British officer charged with debriefing the steady stream of defectors and refugees from Stalin’s rapidly coagulating empire. That had made Russell suspicious, as had the Russian’s choice of Trieste. Had his superiors calculated that the chances of encountering real professionals would be less in such a relative backwater? If so, they’d done their homework well.

The Russian lit another cigarette and said, for the fourth or fifth time, that the MGB would be frantically looking for him, and that he would be of no use to ‘the great world of freedom’ if his new friends allowed him to be killed. Surely it was time to move him somewhere safe, where they could discuss what sort of life they were offering in exchange for everything he knew?

Russell translated this as faithfully as he could; so far that day he had seen no potential benefit in concealing anything specific from the two English-speakers.

‘Tell him he’s quite safe here,’ Farquhar-Smith said reassuringly. ‘But don’t tell him why,’ he added for the third time that morning, as if afraid that Russell had the attention span of a three-year-old.

He did as he was told, and was treated to another look of hurt incomprehension from Kuznakov. Russell had a sneaking feeling that the Russian already knew about the tip-off, and the two Ukrainians in the Old City hotel. He said he was worried, but the eyes seemed very calm for a man expecting his executioners.

With that thought, the telephone rang. Dempsey answered it, while the rest of them sat in silence, trying in vain to decipher the American’s murmured responses. Call concluded, they heard him go outside, where the half-dozen soldiers had been waiting all morning. A few minutes later he was back. ‘They’re on their way,’ he told Russell and Farquhar-Smith. ‘They’ll be here in about ten minutes.’

‘Just the two of them?’ Russell asked, in case Dempsey had forgotten.

‘Yeah. You take Ivan here out to the stables, and we’ll come get you when it’s all over.’

‘But don’t tell him anything,’ Farquhar-Smith added. ‘We don’t want him getting too high an opinion of himself.’ He gave the Russian a smile as he said it, and received one back in return.

They deserved each other, Russell thought, as he escorted the Russian across the courtyard and down the side of the villa to the stable block. There were no horses in residence; all had been stolen by the locals three years earlier, after the Italian fascist owner’s mysterious plummet down the property’s well. A horsey odour persisted, though, and Russell took up position outside the entrance, where the sweeter smell of pine wafted by on the warm breeze, his ears listening for the sound of an approaching vehicle. Kuznakov had asked what was happening, but only belatedly, as if remembering he should. There was watchfulness in the Russian’s eyes, but no hint of alarm.

In the event, the two Ukrainians must have parked their car down the road and walked up, because the first thing Russell heard was gunfire. Quite a lot of it, in a very short time.

In the enduring silence that followed, Russell saw the look on Kuznakov’s face change from slight trepidation to something approaching satisfaction.

The birds were finding their voices again when Dempsey came to fetch them. The two would-be assassins were lying bloody and crumpled on the courtyard stones, their British killers arguing ownership of the shiny new Soviet machine pistols. Neither of the dead men looked particularly young, and both had tattoos visible on their bare forearms which Russell recognised. These two Ukrainians had fought in the SS Galician Division; there would be other tattoos on their upper arms announcing their blood groups. Strange people for the MGB to employ, if survival was desired.

There was no sign that Dempsey and Farquhar-Smith had worked it out. On the contrary, they seemed slightly more respectful toward their Soviet guest, as well as eager to continue with the interrogation. Not that they learned very much. Over the next three hours Kuznakov promised a lot but revealed little, teasing his audience with the assurance of a veteran stripper. He would only tell them everything when he really felt safe, he repeated more than once, before casually mentioning another cache of vital intelligence which he could hardly wait to divulge.

It was almost six when Russell’s bosses decided to call it day, and by that time the four of them could barely make each other out through the fug of the Russian’s cigarette smoke. Outside, the sky was clear, the sun sinking behind the wall of pines which lined the southern border of the property. Leaving Farquhar-Smith to sort out the nocturnal arrangements, Russell and Dempsey roared off in the latter’s jeep, and were soon bouncing down the Ljubljana road, city and sea spread out before them. There was already an evening chill, but the short drive rarely failed to raise Russell’s spirits, no matter how depressing the events of the day.

He had been in Trieste for two months now, having been loaned out by the American Berlin Operations Base – ‘BOB’ for short – for ‘a week or two’, after the local Russian interpreter’s wife had been taken ill back home in the States. At this point in time, all the American intelligence organisations in Europe – and there were a bewildering number of them – had only three Russian speakers between them, and since Russell was one of two in Berlin, a fortnight’s temporary secondment to the joint Anglo-American unit in Trieste had been considered acceptable. And by the time news arrived that his predecessor had died in a New Jersey highway pile-up, a veritable flood of interesting-looking defectors had stumbled into Trieste with stories to tell, and Russell had been declared indispensable by Messrs Farquhar-Smith and Dempsey. A replacement was always on the way, but never seemed to arrive.

In truth, Russell wasn’t altogether sorry to be away from Berlin. He missed Effi, of course, but she was currently shooting another movie for the Soviet-backed DEFA production company, and he knew from long experience how little he saw her when she was working. The German capital was still on its knees in most of the ways that counted, and over the previous winter the threat of a Soviet takeover had loomed larger with each passing week. Having failed to win control of the city through political chicanery, the Russians had opted for economic pressure – exploiting the Western sectors’ position deep inside the Soviet Zone, and their consequent reliance on Russian goodwill for all their fuel and food. Until a couple of weeks ago, it had all seemed little more than gestures, but on April Fool’s Day – a scant twenty-four hours after the US Congress approved the Marshall Plan – the Soviet authorities in Germany had upped the stakes, placing new restrictions on traffic using the road, rail and air corridors linking Berlin with the Western zones. This had continued for several days, until a Soviet fighter had buzzed an American cargo plane a little too closely and brought them both down. Since then, things had got back to normal, although no one knew for how long.

Berlin’s intelligence outfits would still be in a frenzy, and that was something worth missing. His American controller Brent Johannsen, though a decent enough man, was handicapped by his ignorance of Europe in general and the Soviets in particular, and his misreading of the latter’s intentions could be downright dangerous to his subordinates. Russell’s Soviet controller Andrei Tikhomirov was usually too drunk to bother with orders, but in January he and Yevgeny Shchepkin had been farmed out to one of the new K-5 whizkids, a young Berliner named Schneider, who seemed to think the best way to impress his Russian mentors was to behave like the Gestapo.

No, Effi might be calling him home, but Berlin most definitely wasn’t.

Trieste was a monument to failure, a city crowded with people who only wanted to leave – it often reminded Russell of a film called Casablanca, which he’d seen during the war – but the food and weather were a huge improvement on Berlin’s. And the ‘Rat Line’ story Russell had been working on for over a month was making him feel like a journalist again. Over the last three years he had almost forgotten how much he enjoyed digging up such stories, sod by clinging sod.

‘This okay?’ Dempsey asked him, breaking his reverie. The American had stopped outside a tobacconist’s about halfway down the Via del Corso. ‘I need a new pipe,’ he added.

In the distance there was some sort of demonstration underway – in Trieste there usually was. Yugoslavs wanting the Italians out, Italians wanting the Yugoslavs out, everyone keen to see the backs of the Brits and the Yanks.

Russell thanked Dempsey for the lift, and took the first turning into the Old City’s maze of narrow streets and alleys. His hostel was on a small plaza nestling beneath the steep slope of St Giusto’s hill, a Serb family business which he had judged much cleaner than its Italian neighbour. The supply of hot water was at best sporadic, and his clothes always came back from washing looking remarkably untouched by soap; but he liked the proprietor Marko and his ever-cheerful wife Mira, not to mention their seven or eight children, several of whom were almost always guaranteed to be blocking the staircase with some game or other.

There was no one at the desk, no post for him in the pigeonhole, and only one daughter on the stairs, twirling hair between her fingers and deep in a book. Russell worked his way round her and let himself into his home away from home: a room some five metres square, with an iron bedstead and faded rug, an armchair that probably remembered the Habsburgs, and, by day, a wonderful view of receding roofs and the distant Adriatic. The bathroom he shared with his mostly Serbian fellow-guests was just across the hall.

Russell lay down on the over-soft bed, disappointed but hardly surprised by the lack of a letter from Effi – even when ‘resting’, she had never been a great correspondent. To compensate, he re-read the one from Paul, which had arrived a few days earlier. As usual, his son’s written language was strangely, almost touchingly, formal. He was marrying Marisa on Friday the 10th of September, and the two of them hoped that Effi and his father would do them the honour of attending the ceremony at St Mary’s in Kentish Town. Solly Bernstein, Russell’s long-time British agent and Paul’s current employer, would be giving the bride away, Marisa’s parents having died in a Romanian pogrom. Solly also sent his love, and wanted to know where the new story was.

‘I’m working on it,’ Russell muttered to himself. London, like September, seemed a long way away.

He looked at his watch and heaved himself back up – he had a meeting with a source that evening, and was hungry enough to eat dinner first. There was still no one on the desk downstairs, and the drunken English private hovering in the doorway was looking for a less salubrious establishment. Russell gave him directions to the Piazza Cavana, and watched the man weave unsteadily off down the cobbled street. Removing his trousers without falling over was likely to prove a problem. The restaurants on the Villa Nuova were already doing good business, with some hardy souls sitting out under the stars with their coats buttoned up. Russell found an inside table, ordered pollo ai funghi, and sat there eating buttered ciabatta with his glass of Chianti, remembering his and Effi’s favourite trattoria on Ku’damm, back when the Nazis were just a bad dream. An hour or so later, he was back in the Old City, climbing a narrow, winding street toward the silhouetted castle. A stone staircase brought him to the door of a run-down delicatessen, whose back room doubled as a restaurant. There were only four tables, and only one customer – a man of around forty, with greased-back black hair and dark limpid eyes in a remarkably shiny face. He wore a cheap suit over a collarless shirt, and looked more than ready to play himself in a Hollywood movie.

‘Meester Russell,’ the man said, rising slightly to offer his hand, after wiping it on a napkin. A plate with two thoroughly stripped chicken bones sat on the dirty tablecloth, along with a half-consumed bottle of red wine.

‘Mister Artucci.’

‘Call me Fredo.’

‘Okay. I’m John.’

‘Okay, John. A glass,’ he called over his shoulder, and a young woman in a grey dress almost ran to the table with one. ‘You can close now,’ Artucci told her, pouring wine for Russell. ‘My friend Armando tell me you interest in Croats. Father Kozniku, who run Draganović’s office here in Trieste. Yes?’

Russell heard the woman let herself out, and close the door behind her. ‘I understand your girlfriend works in the office,’ he began. ‘I’d like to meet her.’

Artucci shook his head sadly. ‘Not possible. And I know everything from her. But money talks first, yes?’

‘Always,’ Russell wryly agreed, and spent the next few minutes patiently lowering the Italian’s grossly inflated expectations to something he could actually afford.

‘So what you know now?’ Artucci asked, lighting a cigarette which smelled even worse than Kuznakov’s brand.

Russell gave him a rundown. The whole business had come to his attention while on a fortnight’s secondment to the CIC office in Salzburg the previous year. The Americans, having decided not to prosecute a Croatian priest named Cecelja for war crimes, had started employing him as a travel operator for people they wanted out of Europe. As he investigated the latter over the next few months, it became clear to Russell that Cecelja, far from working alone, was just one cog of a much larger organisation, which was run from inside the Vatican by another Croatian priest named Krunoslav Draganović. Using a whole network of priests, including Father Kozniku here in Trieste, Draganović was selling and arranging passage out of Central and Eastern Europe for all sorts of refugees and fugitives.

The Americans called the whole business a ‘Rat Line’, but Russell doubted they knew just how varied the ‘rats’ had become. In addition to those thoroughly debriefed Soviet defectors whom the American CIC was set on saving from MGB punishment, Russell had so far identified fugitive Nazis, high-ranking Croat veterans of the fascist Ustashe, and a wide selection of all those East European boy’s clubs which had clung to Hitler’s grisly bandwagon. The Americans were paying Draganović $1,500 per person for their evacuees; but the others, for all he knew, were charity cases.

Artucci listened patiently, then blew out smoke. ‘So, what are your questions?’

‘Well, first off – are Draganović and his people just in it for the money? Or are they politically motivated, using the money they get from the Americans to subsidise a service for their right-wing friends?’

‘Mmm,’ Artucci articulated, as if savouring the question’s complexity. ‘A little of both, I think. They like money; they don’t like communists. All same, in the end.’

‘That’s not very helpful,’ Russell told him, putting down a marker.

‘Well, what I say? I no see inside Draganović mind. But Croat people he help – they kill for fifteen dollar. They only see fifteen hundred in dreams.’

‘Okay. So, as far as you know, have the Americans only bought exits for Soviet defectors and refugees? Or have they shelled out for Nazis and Ustashe as well?’ This was the key question in many ways. If the Americans, for whatever twisted political reasons, were helping certain war criminals escape Europe and justice, then he had a real story. Not one his American bosses in Berlin would want published, but with any luck at all they would never know the source. For over a year now, Russell had been using a fictitious by-line for the stories which might upset one or both of his Intelligence employers, and the elusive Jakob Brüning was becoming one of European journalism’s more respected voices. As far as Russell knew, only Solly and Effi were aware that he and Brüning were one and the same.

Artucci was pondering his question. ‘Is difficult,’ he said at last. ‘How I say? All these people – the Americans, the British, Draganović and his people – they all have agenda, yes? This Rat Line just one piece. I don’t know if Americans pay Draganović for Nazis or Ustashe to escape, but they all talk to others. Here in Trieste. And British, they talk to Ustashe, give them guns. And everyone know they help Pavelić escape, everyone. Why they do that, if not to please his Križari, the men they want to fight Tito and the Russians?’

He was probably right, Russell thought. It was hard to think of the Ustashe as acceptable allies in any circumstances – they had routinely committed atrocities the Nazis would have shrunk from – but, as Artucci said, the Allies had indeed spirited the appalling Ustashe leader Ante Pavelić away to South America. And what were the Americans’ current alternatives? When it came to potential allies, they were understandably – if somewhat foolishly – reluctant to put their faith in Social Democrats, which only left the parties of the tainted Catholic right. Nazi collaborators, fascists in all but name, but reliably anti-Communist. Everyone knew the Križari – the Croat ‘Crusaders’ – were Ustashe in fresh clothes, but as long as they took the fight to Tito, they had nothing to fear from the West.

Asked for names, Artucci grudgingly provided two – young men from Osijek with lodgings near the train station, who had been hanging around Kozniku’s office for the last week or so. They were waiting for something, Artucci thought. ‘And they pester my Luciana,’ he added indignantly. He offered to provide more names on a pro-rata basis, provided Russell could guarantee his anonymity. ‘Some of these people, they think murder is nothing.’

But he didn’t seemed worried as he walked off into the darkness, Russell’s dollars stuffed in his money-belt and a definite spring to his step. Russell gave him a start, then headed down the same street. Artucci was probably less informed than he thought he was, but he might well have his uses.

Reaching his hostel, Russell decided it was too early to shut himself away for the night, and continued on towards the seafront. Halfway along one narrow street, he became aware of footsteps behind him, and carefully quickened his pace before glancing over his shoulder. A man was following him, though whether deliberately was impossible to tell. There was no sign of hostile intent, and the footsteps showed no sign of quickening. Keeping his ears pricked, Russell kept walking, and eventually the man took a different turning. Russell sometimes got the feeling that putting the wind up strangers was a hobby among Triestinos.

He ended up, as usual, in the Piazza Unità. The city’s social hub boasted a well-kept garden with bandstand, and five famous cafés established in Habsburg times. Russell’s favourite was the San Marco, where writers had traditionally gathered. According to legend, James Joyce had worked on Ulysses at one corner table, from where he was frequently collected by his furious mistress, the exquisitely-named Nora Barnacle.

The café was about half-full. Russell ordered a nightcap, filched an abandoned Italian newspaper from an adjoining table, and idly glanced through its meagre contents. Nothing looked worth a laborious translation. When the small glass of ruby-red liquid arrived he sat there sipping and thinking about the next day. Another eight hours of Kuznakov and his cigarettes, of Farquhar-Smith and Dempsey and their stupid questions. Russell didn’t know which he loathed the more – the Army intelligence types thrown up by the war, who had no idea what they were doing, or the new professionals now making their mark in Berlin, who were too dead inside to know why they were doing it.

Russell was nursing an almost empty glass when the door swung wide to reveal a familiar figure. Yevgeny Shchepkin looked round the room, betrayed, with only the faintest curl of his lips, that he’d noticed Russell, and took a seat at the nearest empty table before removing his hat and gloves. A waiter hurried towards him, took his order, and returned a few minutes later with a cup of espresso. Taking his first sip, the white-haired Russian made eye contact for the first time. As he lowered the cup a slight movement of the head suggested they meet outside.

Russell sighed. He hadn’t expected to see Shchepkin here in Trieste, but the Russian had a habit of appearing at his shoulder, both physically and metaphorically. He rarely brought good news but, for reasons he never found quite convincing, Russell was fond of the man. Their fates had been intertwined for almost a decade now, first in working together against the Nazis, and then in a mutual determination to escape the Soviet embrace. His family in Moscow were hostages to Shchepkin’s continued loyalty, while Russell was constrained by Soviets threats to reveal his help in securing them German atomic secrets. As far as Stalin and MGB boss Lavrenti Beria were concerned, Russell was a Soviet double-agent, Shchepkin his control. As far as the Americans were concerned, the reverse was the case. All of which gave Russell and Shchepkin some latitude – helping ‘the enemy’ could always be justified as part of the deception. But it also tied them into the game they both wanted out of.

After paying his check Russell wandered out into the square. A British army lorry was rumbling past on the seafront, offering material support to the Union Jack that fluttered from the top of the bandstand. The sky was clear, the temperature still dropping, and he raised his jacket collar against the breeze flowing in from the sea.

Shchepkin appeared about five minutes later, buttoning up his coat. Russell had a sudden memory of a very cold day in Krakow, and the Russian scolding him, almost maternally, for not wearing a hat.

They shook hands, and began a slow circuit of the gardens.

‘Have you just come from Berlin?’ Russell asked in Russian.

The Russian nodded.

‘How are things? In Berlin, I mean.’

‘Interesting. You remember the big shake-up last September? Someone at the top had the bright idea of merging the MGB and the GRU, so KI was set up. It felt like a bad idea then, and things have only gotten worse. These days nobody seems to know who they’re accountable to, or who they should be worrying about. Different groups have ended up trying to snatch the same people from the Western zones. Some of our people in Berlin recruited KI staff as informers without knowing who they were.’

Shchepkin was always exasperated by incompetence, even that of his enemies. ‘And the wider picture?’ Russell asked patiently. He hadn’t had the trials and tribulations of the Soviet intelligence machine in mind when asking his question.

‘Serious,’ Shchepkin said. ‘I think Stalin has decided to test the Americans’ resolve. It won’t be anything dramatic, just a push here, a push there, nothing worth going to war over. Just loosening their grip on the city, one finger at a time, until it drops into our hands.’

‘It won’t work,’ Russell argued, with more certainty than he felt. He didn’t doubt the Americans’ will to resist, just their ability to work out the how and when.

‘Let’s hope not,’ Shchepkin agreed. ‘We might both prove surplus to requirements if Stalin gets his way. But…’

A shot sounded in the distance, several streets away. This wasn’t an uncommon occurrence in Trieste, and rarely seemed to have fatal consequences.

‘You were saying?’

‘Ah. Your absence has been noticed, even by Tikhomirov. And young Schneider misses you greatly,’ he added wryly. ‘He suspects you’re prolonging your stay here for no great reason.’

‘You can tell Schneider I’m prolonging my stay here to avoid seeing him –’

‘I don’t –’

‘– but the real reason is, they won’t let me go. So many of your countrymen are turning up here uninvited, and I’m the only person they have who can talk to them.’

‘I see. Well, maybe I can do something about that. A local volunteer, perhaps?’

‘It would help if your people stopped planting fakes among the real defectors. Kuznakov will probably keep me busy for the next week.’

‘Ah, you spotted him, did you?’ Shchepkin said, sucking in his thin cheeks and sounding like a gratified teacher. ‘You didn’t give him up, though? He’s an idiot anyway, and I can tell my people you helped smooth his passage. We need every success we can get.’

‘We do? I thought we were doing rather well.’

‘Well, Tikhomirov and Schneider don’t agree. They know that building your credit with the Americans requires the occasional sacrifice of one of their own, but they still don’t like doing it, and they need the occasional reminder that your uses extend to the here and now.’

‘All right. But getting back to the original topic – the Americans are sending me to Belgrade in a couple of weeks, so Berlin will have to wait at least that long.’

Shchepkin was interested. ‘What do they want you to do there?’

‘They’re still deciding. As a journalist, they want me to sound out who I can, find out how real the row is between Tito and Stalin. But if past experience is any guide, they’ll also have a list of people they want me to contact. Potential allies – if they have any left, that is.’

Shchepkin was silent for a few moments. ‘There’s not much difference between journalism and espionage,’ he said eventually, sounding almost surprised.

‘One is illegal,’ Russell reminded him.

‘True,’ Shchepkin acknowledged. ‘Needless to say, we’d like copies of any reports. And there may be people we want you to see. I’ll let you know.’

‘Sounds ominous. If Tito and Stalin really have fallen out, then my Soviet “Get out of jail free” card won’t be worth much.’

‘Your what?’

‘It’s a board game called Monopoly,’ Russell explained. ‘If you land on a particular square, you end up in jail. But if you already have a “Get out of jail free card” you’re released straight away.’

‘Fascinating. And what’s the object of this game?’

‘Bankrupting your opponents by buying up properties and charging them rent each time they land on one.’

‘How wonderfully capitalistic.’

‘Indeed. But returning to the point – I won’t be much use to Berlin if I’m stuck in a Belgrade prison.’

‘I’ll bear that in mind,’ Shchepkin said, with a smile. They had completed one circuit, and were halfway through a second. Away to their left, two British warships were silhouetted against the sea and sky. ‘I was in Prague a few days ago,’ Shchepkin said, surprising Russell. The Russian rarely volunteered information about himself or his other activities.

‘Not much fun?’ Russell suggested. The Communists had taken sole control only six or seven weeks earlier, and shortly thereafter the pro-Western foreign minister Jan Masaryk had allegedly jumped to his death from a window in the Czernin Palace. According to Buzz Dempsey, the borders had been effectively closed ever since, as the Party relentlessly tightened its hold.

‘You could say that,’ Shchepkin said.

‘I expected better of the Czechs.’

‘Why?’

‘You know your Marx. An industrial society, rich in high culture – isn’t that supposed to be the seed-bed of socialism?’

‘Of course. But the Czechs have us to contend with, the peasant society that got there first. And the more civilised the country, the tighter we’ll need to screw down the lid.’

Shchepkin was right, Russell thought. It was the same everywhere. In Berlin his friend Gerhard Ströhm was continually complaining that the Soviets were destroying the German communists’ chances of creating anything worthwhile.

‘Look,’ Shchepkin said, ‘I understand your reluctance to come back to Berlin…’

‘You do?’

‘I know what you were doing before you left; and you’re probably doing the same thing here. Neither side has been choosy about who they recruited, and they’re getting less so with each passing month. Both have taken on a fair proportion of ex-Nazis. To retain your credibility as a double-agent, you have to offer up people on both sides – American agents to us, our agents to the Americans. But as far as I can tell, every last one you’ve betrayed has been an ex-Nazi. You’re still fighting the war.’

‘And what’s wrong with that?’ Russell wanted to know.

‘Two things,’ Shchepkin told him. ‘One, eventually each side will start wondering just how committed you are to fighting their new enemy. And two, you’ll soon be running out of Nazis. What will you do then?’

‘Whatever I have to, I suppose. I was hoping you’d conjure us out of all this before I reached that point. Three years ago you talked about uncovering a secret so appalling that it would work as a “Get out of Stalin’s reach” card. Didn’t some innocent birdwatcher accidentally take a photo of Beria pushing Masaryk out of his window, which we could use to blackmail the bastard?’

‘It was three in the morning.’

‘Pity.’

They both laughed.

‘We’ll meet again on Thursday,’ Shchepkin decided. ‘Here at the same time.’

It was almost midnight, but Russell still felt more restless than sleepy. He walked north up the seafront, passing groups of huddled refugees, and one suspicious stack of crates guarded by a posse of Jews – more guns for the Haganah’s war with the Arabs. Hitler had been dead for almost three years, but so many of the conflicts his war had engendered were still unresolved. A line from a long-forgotten poem came back to Russell: ‘War is just a word for what peace can’t conceal.’

* * *

It was snowing in Berlin: not hard, just a light flurry to remind the city that spring wasn’t fully established. Effi was near the back of the people gathered round the grave in the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, among a crowd of others who had worked with the dead woman – directors and writers, producers and cameramen, other actors. She had shared three film-sets with Sonja Strehl, and one theatre run back when they were both in their twenties. Effi hadn’t seen Sonja for years, and had never known her well, but still she found it hard to imagine the woman committing suicide. Sonja had always seemed so positive. About life, work, even men. And no doubt about the children she’d eventually had, the boy and girl now standing by the open grave, looking like all they wanted to do was cry.

‘Are you coming back to the house?’ Angela Ritschel whispered in Effi’s ear.

‘For a little while.’ They were working on the same film out at Babelsberg and, like the rest of the cast, had grudgingly been given the afternoon off to attend the funeral.

‘She was good, wasn’t she?’ Angela said, a few moments later.

‘Yes,’ Effi agreed. She’d been remembering Sonja backstage at the Metropol, frantically searching through a pile of bouquets for a note from the man she currently fancied. The look on her face when she’d found it.

If truth be told, Sonja hadn’t had much of a range as an actor. But she could make demure look sexy, light up a screen with joy in life, weep until you had to weep with her. And maybe that was enough. People had paid to see her, which had to mean something, Effi thought.

The service was apparently over, the crowd of mourners breaking up. There were two cars for close family, but the rest of them had to walk down Oranienburger Strasse to the house on Monbijou Platz, past the still-closed S-Bahn station and the wreckage of the old Main Telegraph Office.

Inside Sonja’s house, her father was greeting the guests, looking suitably heartbroken. Two of the ex-husbands were there, but not the father of her children – he had been killed entertaining the troops at Stalingrad.

There was a table groaning with food, supplied by her recent Soviet employers, and enough unopened bottles of vodka to induce the traditional Russian stupor. Fortunately, the Americans had also deemed it politic to send their respects in liquid form, so Effi chose a small glass of Bourbon to wash down the Russian hors d’oeuvres. Angela had wandered off, and Effi scanned the crowd for another familiar face. She caught the glance of Sonja’s first husband, the actor Volker Heldt. He and Effi had worked on a DEFA project only the previous year.

He walked across to join her. ‘A good crowd,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ Effi agreed. ‘Don’t look now, but who’s the man leaning against the wall in the grey suit? He keeps staring at me.’

‘Who wouldn’t?’ Volker said gallantly, taking his time to look around. ‘Oh him – he stares at everyone. He’s one of the Russian culture people. MGB most likely. It was their police who found her, you know.’

‘I didn’t. I still can’t believe she killed herself.’

‘Oh, I don’t think there’s any doubt, despite what some people are saying.’

‘How did she do it?’

‘Sleeping pills. And there’s no doubt she bought them. She paid a fortune for them on the black market.’

‘Did she leave a note?’

‘No, and that was strange. But she’d only just broken up with her last boyfriend – the one almost half her age – so who knows what was going through her mind. And anyway, what reason would the Russians have for killing her?’

‘Is that what people are saying?’

‘A few. Like Eva here.’

The blonde joining them had done the costumes on several of Effi’s films. Eva Kempka was in her forties now, and thin enough to look a little stretched. She had been married once, but according to Berlin’s cinematic grapevine, had since changed her sexual proclivities.

‘What are you accusing me of?’ Eva asked Volker, with more than a hint of disdain.

‘Of believing the Russians killed Sonja.’

‘I’ve never said that. I just don’t believe she killed herself.’ The way she said it made Effi think there’d been some emotional involvement, either real or unrequited.

‘Well, maybe not you,’ Volker admitted, ‘but there are a lot of people out there who think the Russians are behind every mysterious happening. Good or bad. And the Russians are really not that smart.’

‘Yes, but Sonja was…’ Eva began, then, for some reason, suddenly stopped.

‘Sonja was what?’ Volker asked.

‘Nothing,’ Eva said quickly. ‘And you’re right about everyone blaming the Russians for everything. But they are in control. They closed down all the help stations on the autobahn yesterday – it took a friend of mine eleven hours to reach Helmstedt.’

‘Are they still closed?’ Effi asked. She had the feeling that Eva had only just realised that she was talking to one of Sonja’s ex-husbands, and was eager to change the subject.

‘I don’t think so,’ Volker answered her. ‘But they could be again tomorrow, and there doesn’t seem much we Berliners do about it. Appealing to the Americans is a waste of time – they’re too scared of starting another war.’

‘A good thing to be scared of,’ Effi argued. ‘But we can’t complain about what the Russians have done for our business – if it hadn’t been for them, there wouldn’t have been any new German films. The Americans would have been happy to sell us theirs, and make the occasional one here using their own crews and actors.’

‘Like Foreign Affair,’ Eva suggested.

‘Exactly. Marlene was the only German with a decent part.’

‘True,’ Volker agreed, ‘but things seem to be changing over the last few months. Last year the Americans were only interested in propaganda, while the Soviets were encouraging thoughtful movies, but these days the roles seem almost reversed. I’ve no idea why.’

‘Neither have I,’ Effi said, having just noticed that the grey-suited Russian was listening intently to their conversation, a dark frown on his face. Actually, Russell had explained it all in a recent letter: the Russians, having interpreted the American Marshall Plan as a declaration of hostilities, were busy battening down every hatch they could, including the cinematic ones.

Another group called Volker away, and Eva seemed to breathe a sigh of relief. But instead of returning to the subject of Sonja, she asked Effi what she was working on.

‘Another film with Ernst Dufring… I agree that the Soviets are becoming less open, but they haven’t stopped people like him making thoughtful films. Not yet, at least.’

‘What’s this one about?’

‘It’s the history of a family, and one woman in particular – Anna Hofmann. The film’s named after her. She starts off as a serving girl in an officer’s family around the turn of the century, has a family of her own, loses her husband and son, and ends up making a dress for her granddaughter’s graduation – they’re the only two left. But it’s not depressing, not really. And it asks a lot of questions.’

‘And who do you play?’

‘The woman in middle age. It’s not a big part, but it’s a good one. Anna Jesek wrote the screenplay, and some of the lines are heavenly. What about you?’

‘Oh, nothing at the moment. No one’s making period dramas – I guess the Nazis made too many – and films set in the last few years are pretty easy to clothe. Any old rags will do.’

‘I suppose so.’

‘So what’s next?’

‘No idea. I’ve got an audition at the American radio station – they’re planning a serial about ordinary Berliners which sounds interesting. And DEFA have offered me a film which doesn’t, although I haven’t seen the script yet.’

‘Will the Russians be happy to let you go?’ Eva wondered.

‘They don’t own me.’

‘No, but they can make life difficult for people.’

‘Well, if they do, I just might take an extended holiday. I need to spend more time with my daughter anyway.’

‘I didn’t know you had one.’

‘We adopted Rosa after the war. Both her parents had been killed.’

‘How old is she?’

‘Eleven and a half.’

‘A difficult age.’ Eva opened her mouth to say something else, closed it, and then took the plunge. ‘Look, I don’t want to talk about it here, but the Russians were making life difficult for Sonja, and I just have to tell someone what I know. Could we meet for a coffee or something? I know you’re busy, but…’

‘Of course. But why me? I hardly knew her.’

Eva smiled. ‘I don’t know. I’ve always thought you were more sensible than most actors.’

A back-handed compliment if ever she’d heard one, Effi thought an hour or so later, as she waited for the tram to carry her back across town. But a coffee with Eva would be pleasant enough. She wondered if the woman had had an affair with Sonja, and what secrets she had to tell. Nothing dangerous, she hoped.

There was no point in worrying about possible problems in the future when she had enough on her plate already. Rosa might be almost twelve, but she could act anything from age six to sixteen. Most of the friends Rosa had made in their neighbourhood were a lot older, and though none of them seemed like bad children, some were definitely on the wild side, with no obvious signs of parental control. At school, where her marks remained high, Rosa’s friends seemed mostly the same age as she was.

Effi’s sister, who looked after Rosa when Effi worked early or late, insisted there was nothing to worry about, and she was usually right about such things. But these days Zarah’s attention was so focused on her new American lover that she wouldn’t have noticed a visit from Hitler. And bringing Rosa back to Berlin had always felt risky to Effi, as the girl had lost both her parents here.

By this time the number of people waiting for the tram exceeded its capacity, but the only alternative was a six-mile walk. Two Soviet soldiers were standing on the far pavement, ogling a young woman in the queue. She was aware of their attention, Effi noticed, and was looking worried. The soldiers hadn’t yet said or done anything, but they didn’t need to – the legacy of the mass rapes which followed the capture of the city was still very much in most women’s minds. And even now, there was nothing to stop those two men walking across the street and simply taking the girl away. The Soviets had no compunction about abducting people from other sectors, and this was their own.

Effi walked over to the young woman, and stood between her and the soldiers. ‘Try to ignore them,’ she urged.

‘That’s easy to say,’ the girl said. ‘I have to get the tram here every day after work, and most days they’re there.’

‘Well, if they haven’t done anything yet, they’re probably too nervous,’ Effi encouraged her. ‘But you could try another way home.’

‘I could. But I don’t see why I should have to.’

‘No,’ Effi agreed.

Two trams arrived in tandem, and sucked up most of the waiting crowd. Effi stood in the crowded aisle, catching glimpses of the still-ruined city, asking herself how long it would be before rebuilding started in earnest, before the foreign occupiers all went home, before it was safe for a woman to walk the streets. She knew what John would say: ‘Don’t hold your breath.’

She got off on Ku’damm, and walked up Fasanen Strasse to the flat which Bill Carnforth had procured for Zarah. It was on the first floor of the middle house in an undamaged row of five, had four spacious rooms, and was only a few minutes’ walk from Effi’s own apartment on Carmer Strasse.

Zarah was cooking dinner, wearing one of her prettiest dresses. Like most Berliners she had been on a forced diet for several years, and in her case the benefits had almost outweighed the cost – she looked better than she had since her twenties. Through the living room door Effi could see Lothar and Rosa hunched over their homework.

‘How was it?’ her sister asked.

‘Depressing. Are you going out with Bill tonight?’

‘I hope so. I’ve cooked you and Rosa dinner in the hope that you’ll babysit Lothar.’

‘Oh all right.’

‘I won’t be late.’

‘I said all right.’

‘I don’t know why you don’t both move in while John’s away. There’s plenty of room.’

‘I…’ Effi pushed the door to. ‘I don’t want to move Rosa again. And John should be back soon.’

‘Have you heard from him?’

‘No, but they can’t keep him down there for ever.’

* * *

Waking up alone, Gerhard Ströhm remembered that Annaliese was on early shift that week. She must have left at least an hour earlier, but her side of the bed was still warm.

He clambered out, walked to the window and drew back the makeshift curtain. The previous evening’s snow had melted away, and the sun was shining in a clear blue sky. Maybe spring had arrived at last.