Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Old Street Publishing

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A John Russell WWII Spy Thriller

- Sprache: Englisch

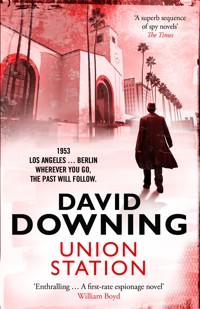

'Enthralling … A first-rate espionage novel' WILLIAM BOYD 1953. Stalin is dead and John Russell's days as a double agent for the USSR and the USA are behind him. Now the British journalist lives a quiet life in Los Angeles with his actress wife, Effi, and their daughter, while around them the McCarthy-era hearings are closing in on Hollywood. But someone is following Russell. Is it because of his research into American firms that collaborated with Nazi Germany? Or his earlier espionage work? Or something else? The answer takes John and Effi back to Berlin, now a city divided, where the fight for Stalin's succession is on. The latest chapter in the John Russell series, David Downing's Union Station is a superbly evocative Cold War thriller.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 587

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ipraise for david downing

‘Excellent and evocative... Downing’s strength is his fleshing out of the tense and often dangerous nature of everyday life in a totalitarian state’

The Times

‘One can only marvel at his talent for infusing such a rangy cast of characters with nuance and soul’

New York Times

‘Think Robert Harris and Fatherland mixed with a dash of le Carré’

Publishing News

‘Tight, intelligent plots full of moral ambiguities, and a cast of shadowy characters for whom deception is as natural as breathing’

Marcel Berlins

‘Epic in scope, Downing’s “Station” cycle creates a fictional universe rich with an historian’s expertise, but rendered with literary style and heart’

Wall Street Journal

‘In the elite company of literary spymasters Alan Furst and Philip Kerr’

Washington Post

ii

UNION STATION

DAVID DOWNING

viiFor the father, mother and brother with whom I grew up, in what now seems a far kinder Britainviii

UNION STATION

Contents

Abbreviations

BOB: The Berlin Operations (or Operating) Base of US intelligence, which by 1953 was a wholly CIA concern

CPSU: The Communist Party of the Soviet Union

DDR: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, known in the West as East Germany

DEFA: Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft–East German film studio sponsored by the Soviets in the first few years after the war

GRU: Soviet military intelligence

MfS: East German security police, aka the Stasi

MGB: The Soviet Ministry of Security from 1946 to ’53, successor to the NKD and precursor of the KGB

RIAS: “Radio in the American Sector” radio station

SED: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (Socialist Unity Party), formed in 1946 by a merging of the communist KPD and socialist SPD in the Soviet sector of occupied Germany. After 1950, East Germany’s ruling partyxii

Prelude

March 10, 1953

“So which magazine are you from?” Stephen Brabason asked. Not, John Russell thought, that the actor really cared. He just wanted to emphasise how many other interviewers were paying court to him that day.

“I work for a couple of newspapers,” Russell told him. “One in England, one in Germany.”

“Oh,” the actor said, sounding almost interested. “Do you speak German?”

“I do. I lived there for a time. Immediately after the war,” he added, because letting on that he’d also been there for most of the inter-war years rarely elicited a positive response. “And I know you have a lot of fans in that country,” he said ingratiatingly.

Brabason let slip the smile which had launched quite a clutch of B movies, and, of late, a smattering of As. Russell was at a loss as to how or why. Having watched the latest, a sub-Hitchcock murder mystery in which Brabason played the second male lead and heroine’s saviour, Russell knew the man was only capable of playing one character, albeit in a stunning variety of costumes. And having now met the man, it was the clear that the character in question was Brabason’s idealised version of himself.

The actor was finishing work on a romantic weepie called Her Decision, which centred on a couple taking in the heroine’s dead sister’s children after she and her husband have both been struck by the same bolt of lightning. Russell, invited to a prerelease 2screening, had followed Effi’s advice and kept an eye out for the decision in the title, and been suitably impressed by the accuracy of her prediction that he would wait in vain. “So what drew you to Her Decision?” he asked Brabason. Apart from the money and the fact that his agent had urged him to do so.

The actor thought about his reply, which said something for his professionalism, if not the film.

“Was it the chance to work with Meredith Kissing?” Russell asked. Any on-screen chemistry between the two was notable by its absence, but that, according to Russell’s actress wife, Effi, was because both leads were more interested in partners of their own gender. A common enough Hollywood occurrence, but not one that received much of an airing in the press.

“Well, she’s an absolute sweetheart, of course. And we do work well together.”

“Would you say the story is about redemption?” Russell asked. “Risible redemption” had been Effi’s verdict when he outlined the film’s plot to her.

“Well, yes, I can see that,” Brabason agreed, reaching for his cigarettes and offering the packet.

Russell declined. “Your character feels partly responsible,” he suggested helpfully.

“For his nephew’s death, yes. And it forces him to go the extra mile.” The actor offered up his smile again, this time through a suggestive cloud of smoke.

Russell remembered Effi and their adoptive daughter, Rosa, imagining the conversation in the writers’ room as they came up with the ludicrous denouement, and stifled a laugh. Get a grip, he told himself, not for the first time in his short career as a Hollywood reporter. “What was your own childhood like?” he asked.

The actor had a two-drag think. “Fine,” he said tentatively. “Normal,” he added with rather more enthusiasm. “We weren’t poor, but we certainly weren’t rich. Just average Joes in an average 3town. To answer your earlier question, I think that’s why I’m drawn to characters like Martin in Her Decision. They’re the backbone of America.”

Russell wondered how many average American Joes became the pirates, trapeze artists, and brain surgeons Brabason had played, but saw no point in asking. How could he get anything that his readers might find interesting out of this man? “How did you get to Hollywood?” he asked, for want of anything better.

“By bus,” Brabason said, with what actually looked like a genuine smile. He tapped ash into the ashtray. “I’d done some acting in high school, and the drama teacher knew someone who knew someone out here and I was invited to come for a screen test. So I sat on a Greyhound for two days, and when I got here I passed the audition.”

The man was good-looking, Russell conceded, though less so in the flesh than on screen. And older.

“The parts were small to start with, but they got bigger and bigger. And I like to think I improved as an actor.”

“And do you think your films have got better?” Russell asked, knowing it was a loaded question. The man hadn’t yet made one that anyone would remember. His entire output ranged between poor and mediocre.

“In what way?” Brabason asked.

“Well, the better an actor gets, the more he needs the scope that complex characters and psychological themes provide.”

“More complex than Her Decision, you mean,” the actor said, surprising Russell. “We can’t all be Laurence Olivier. Or, God help us, Marlon Brando. And lots of people like simple stories with straightforward characters who just get on with the job.”

“They do,” Russell agreed. “So can I ask you about some of your other films and characters?”

He did so, and the actor’s answers and anecdotes, though rarely enlightening, were soon copious enough to fill out a 4thousand-word piece. “And the future?” Russell asked in conclusion. “Any new projects your fans would like to hear about?”

There was one, a war movie about a bunch of GIs island-hop-ping their way across the Pacific. It was an ensemble piece, according to Brabason, and less gung ho than the usual fare. “It’s actually a damn good script,” the actor said, as if he couldn’t quite believe it.

Russell thanked him for his time, and made his way out through the Culver Studios complex. “Nice, isn’t he?” the blonde receptionist said as he handed in his pass.

Walking across the car lot, Russell had to admit that Brabason had been hard to dislike. If his physical and mental attributes were hardly exceptional, his luck certainly had been, and who could blame him for that? Effi might not agree, but making bad movies wasn’t a crime.

The sun was still losing out to the clouds, the temperature noticeably higher than it had been an hour ago, but still cool by LA standards. For Russell, who’d lived all but the last three years of his life in more temperate climates, it felt extremely comfortable. Rain was expected later that day but would probably be over before he had time to raise his convertible’s roof.

He let himself into the blue Frazer and worked his way out of the lot and onto Washington Boulevard, thinking ahead to lunch. His favourite diner was out on the coastal highway, a drive that would have felt long in Berlin but here seemed almost inconsequential. A walk on the beach before he ate would make the food taste even better.

He drove west on Washington, then north through Venice and Santa Monica and onto the road that followed the coast. The beaches to his left were sparsely populated, and it was hard to pick out a horizon between the dull grey sea and sky. He passed the Casa del Mar Hotel, outside which some hopeful starlet in a shiny dress was having her picture taken by a posse of 5cameramen, and was soon on the open highway, joining a two-way procession of huge gleaming trucks spewing out dark exhaust. The traffic thinned out a little after the intersection with Sunset, and a few minutes later he was pulling into the diner’s lot. The smell of bacon almost sucked him in, but three years in Los Angeles had taught him that lengthy walks were the only way for his body to survive a way of life built around motoring.

He crossed the highway and walked down through an area of shaded picnic tables to the sandy beach. The tide was neither in nor out; the only people in sight were around two hundred yards away, walking eastward with a couple of dogs. Russell started off in the other direction. Even under such a dull sky, it felt like a beautiful spot: on one side the ocean stretching into the distance, on the other the wooded mountains rising behind the highway and its narrow strip of houses and small businesses.

As he walked, he went back over the interview. It would make for an adequate article, but nothing more—he would never win acclaim as a film critic. During his life in Germany he had always liked the cinema, but—as he now realised—the films on offer in Berlin had covered a much broader spectrum than those on show in LA. He had grown up with everything from art films to escapist trash and had learned that any genre could be handled badly or well. Here in Hollywood the palette seemed much more restricted, much more focused on appealing to the lowest common denominator. And according to Effi, things were getting worse rather than better: actresses who’d flourished with noir were being returned to their prewar boxes; more and more writers were relying on self-censorship to avoid falling foul of the dreaded McCarthy.

And then there was the context. Russell and his son, Paul, had often enjoyed a Western in prewar Berlin, but watching them here in LA it was harder to get past the role they seemed to play in American life, reinforcing myths and outright lies about the country’s history. 6

When Effi and he had decided three years earlier that she should accept a film offer from a Hollywood studio, they and their adopted daughter had come out to LA for what they assumed was only a few weeks’ well-paid work for his wife and an extended vacation for himself and Rosa. But one film had led to another, and a school was found for a reluctant Rosa, which brought on her English in leaps and bounds. Not wanting to sit around all day admiring the newly refurbished Hollywood sign, and thinking it might be fun to interview Hollywood stars and attend lavish receptions, Russell had asked Solly Bernstein—his long-term agent in London, and the man for whom his son and daughter-in-law now worked—to find him work as a Hollywood/ California correspondent. Solly had duly obliged, fixing Russell up with the two papers he’d mentioned to Brabason.

It had been fun for a while, but after six months or so the vacuousness at the heart of it all had begun to wear on him. After more than thirty years of wars, revolutions, and other horrors, he found it impossible to take Hollywood seriously. A job was a job, but he wasn’t learning anything useful, and that, he realised, was important to him. It wasn’t as if they needed the paltry money he was making—Effi was earning more than enough for all of them, and then some.

Early in 1952 she had stepped into the part of the housekeeper in Please, Dad, a popular radio show about a widower and his two children and had quickly become an audience favourite. There were already rumours that the show was destined for television in the season starting that fall, and Effi, unlike the current children and neighbours, looked the right age for the part. By the end of that year the TV version had been running for three months, and she was fast becoming a household name among the increasing number of US citizens who owned a TV set.

Rosa meanwhile had grown more accustomed to American life and discovered more than a few things she liked about it: the 7sunshine, the food, the sea, new friends. If she was missing Europe she was hiding it well.

And all of them, Russell knew, felt safer here. Five years had passed since his showdown with Stalin’s enforcer Lavrenti Beria, but it still felt like dangerously unfinished business. Barring a life on the moon, he, Effi, and Rosa were about as far away from Moscow and Beria as they could get, and that was how he liked it.

He should count his blessings, Russell thought, because there were certainly plenty of them. Probably more than he deserved.

A particularly noisy truck rumbled past, making him realise how accustomed he’d grown to the steady stream of traffic a hundred yards to his right. Above it, skimming the mountain slope, two large birds were soaring and swooping in search of prey. To his left, a couple of small white boats were sailing close to shore, and out beyond them what looked like a sizable freighter was heading out into the Pacific. Way up ahead, someone was walking towards him. Behind him there were only empty sands.

Someone on one of the white boats was shouting something to someone in the other, barely audible above the wash of the incoming tide. The trucks were still lumbering by. He was surrounded by people, but only as extras, as part of the scenery. Out of reach.

“In a lonely place,” Russell murmured to himself. A film he and Effi had seen and loved during their first few months in LA. Bogie at his best. And the wonderful Gloria Grahame.

The approaching walker was now about three hundred yards away. A man, it looked like, and one wearing a longish coat. A raincoat perhaps—they were not uncommon. It seemed too bulky for that, though, and overcoats really were unusual, even in LA’s so-called winter. There was something about the figure that made Russell think of Russia.

He resisted the sudden urge to turn and run. He’d been thinking about Beria, and here he was imagining that this might be the Soviet leader’s agent, when there was no reason on earth why his 8enemy should have decided, after five long years, that killing his blackmailer had become a safe thing to do.

Almost in spite of himself, Russell was still walking, and the gap between him and the now-obvious overcoat had reduced to fifty yards. He could make out the man’s face under his hat; the Latin colouring and thin lips brought Jacques Mornard to mind, but Trotsky’s assassin was still in a Mexican prison. Or was he?

Twenty yards. The man had both hands in his overcoat pockets, and there was a faint smile on his face, a sheen of moisture above the upper lip. He wasn’t Hispanic, Russell realised, as the right hand emerged from its pocket with something shiny, and his own stomach dropped through the floor.

The “something shiny” was a long-stemmed pipe. “Good morning,” the stranger said cheerily with an English accent.

“Good morning,” Russell echoed, feeling the cold sweat on his back.

The man was already past him.

Turning his head, Russell saw the pipe slipped back into its pocket. Had his imaginary Soviet agent been as anxious as he had? Had pulling the pipe out been a nervous reaction?

And only a Brit would wear a thick overcoat on a day like this.

Once his non-assassin was a decent distance away, Russell turned back in his wake towards the diner. He felt decidedly shaky, and more than a little foolish, but was inclined to forgive himself. This particular apparition had not been sent to kill him, but the enemy was real and certainly had no shortage of agents, as Russell knew only too well.

His own decade-long career in espionage had begun on the first day of 1939, when Soviet agent Yevgeny Shchepkin had recruited him to write articles for the Soviet press extolling the plusses of Nazism. It had, he hoped, ended in late 1948, when he and Shchepkin had secured their release from their perilous roles 9as double-double-agents for both the Soviets and the Americans with the help of a film showing Stalin’s enforcer Lavrenti Beria engaged in rape and murder. After hiding their copies of the film, they had threatened Beria with exposure if anyone close to them died a suspicious death. His acceptance of the deal had cut their ties with the Soviets, and shorn of these, they were no use to the Americans. Russell was free, and Shchepkin would have been, too, if he hadn’t already been terminally ill.

And so far the deal had held. Russell had destroyed his copy of the film at Shchepkin’s suggestion, but the Russian’s copy was still presumably wherever he had left it. Russell could see no reason why Beria would take the risk of reneging on their bargain. But people made mistakes, let emotion override reason. People went mad, got terminally ill. Such a possibility, and the fear that went with it, might seem fainter with each passing year, but it was still there at the back of Russell’s mind, as the last fifteen minutes had made abundantly clear. And maybe Stalin’s death the previous week would shake things up in ways that Russell couldn’t anticipate. Beria might be stepping into Stalin’s shoes at this very moment and imagining himself beyond accountability for even the worst of crimes.

Only Beria’s death would truly free them, Russell thought, as he patiently waited for a gap in the traffic to re-cross the highway. Though perhaps they’d need to ram a stake through his heart as well.

The diner’s lot had thinned out a little in the lull between breakfast and lunch. One reason Russell liked the place was the shelf of newspapers just inside the door, which reminded him of Berlin coffee houses and provided, on this occasion, a choice between the LA Times and Examiner. He took the Times, not because he preferred its right-wing opinions, but because it reflected the views of the current city establishment, and thereby offered a surer indicator of the way things were going, at least in business and politics. 10

There were a couple of empty booths on the city side, which sometimes boasted a distant view of downtown, but today only offered a highway and beach fading into greyness. The menu was happily unchanged, and as he pondered the choice between meat loaf, turkey club, and the all-day breakfast, the waitress arrived with the first instalment of his bottomless coffee. She looked like a teenager, and probably was one. “The club sandwich,” he decided.

“Chips or fries?”

“Fries.”

She almost skipped back towards the kitchen, stopping to top up a couple of coffees en route.

Russell skimmed his way through the paper, finding as usual that violence in varying forms haunted most of the stories. The numbing procession of traffic deaths felt like a minor war, and few days passed without several people succumbing to a knife or a gun. The Korean War carried on exacting its daily toll of deaths, though the respective numbers—thousands on the communist side for every ten in the United Nations—seemed more like propaganda than reporting. More unusually, but well in tune with the times, a schoolteacher suspended for hitting a pupil who “refused to look him in the eye” had just been reinstated.

The anti-communist theme was not restricted to the Korean War coverage. On the contrary, it turned up all over the place, from the latest doings of Senator McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee to a city scheme for putting school textbooks on public display before they were board-approved. This would allow Brabason’s “Average Joes” to decide whether the tomes in question were subversive. One of the books involved was The Robin Hood Stories, and Russell found himself wondering whether it was possible to conceive of Errol Flynn as a socialist.

Rather like McCarthy, the latest rabies scare was also refusing 11to disappear. Three dogs and one cat had joined the ten other pets who had tested positive and were presumably now on death row. Or more likely already ashes. Russell congratulated himself and Effi on resisting Rosa’s plea for a dog.

In what he supposed was better news, “a noted nutrition expert” at the Harvard University School of Public Health had urged all Americans to eat steaks and ice cream for breakfast, and tiny but frequent meals through the rest of the day. Russell thought that a few hours off-campus might rid the “expert” of his delusion that everyone could afford to eat steak, at breakfast or any other time.

His own meal arrived, the piled-high sandwich held together by toothpicks. Even jettisoning the third layer of bread it was enormous, but he ploughed bravely on, pleasure holding the guilt at bay.

Over a refilled coffee he reluctantly went back to the paper, and the news that might actually affect him. Yesterday had seen Stalin’s funeral in Moscow. There was a lengthy article describing the ceremony, one unusually free of ideological insults, as if even the LA Times recognised that someone of real significance had passed away. A psychopathic shit to be sure, but no one could doubt his influence. He had played a not insignificant role in making and then defending the most thoroughgoing revolution of the century, and then played a pivotal role in betraying most of what it stood for. He had caused or decreed the death of millions of innocent Soviet citizens, and after a shockingly incompetent start had efficiently deployed his own implacable brutality to save the world from the Nazis.

Of late Stalin had reportedly become less predictable, and Russell guessed that the Politburo colleagues he’d left behind were probably wetting themselves with relief. They weren’t saying so, of course. According to the Times, Georgi Malenkov, now first among equals if the order of speaking was anything to go by, was 12still hailing “our teacher and leader, the greatest genius of humanity.” He was also suggesting a meeting with Eisenhower, which Stalin had neglected to do, and saying he considered it his “sacred duty” to continue a “peace policy” that the genius had apparently been keen on. Beria had spoken next, which felt ominous to Russell, and had also stressed how devoted he was to peace. So, surprise surprise, was third-placed Molotov.

On the very next page they were all there in photographs, carrying the coffin, lining the tomb, saying their pieces. Russell stared long and hard at Beria, now looking considerably fatter but every bit as vicious as he had when projected onto their Berlin apartment wall four years earlier. It wasn’t over, he thought, without knowing why.

Looking up he saw sundry Americans sat in the booths and at the counter, talking, eating, and drinking, going about their lives. Moscow was closer than they thought, and not in the way Joe McCarthy meant. Russell didn’t think Beria would have any more time for Robin Hoods than the senator did.

GERHARD STRÖHM WOKE UP IN his Moscow hotel bed feeling decidedly hungover. He had never been much of a drinker, and hadn’t imbibed a great deal the previous evening, but was still willing to bet that he felt worse than his fellow German delegates, all of whom had happily kept pace with their Soviet hosts. Party leader Walter Ulbricht and state president Otto Grotwöhl had been knocking them back like there was no tomorrow, and Neues Deutschland editor Rudolf Herrnstadt hadn’t been far behind. At the end of the evening only Ströhm and Wilhelm Zaisser, the Minister of State Security, had managed to navigate their way through the elevator doors at the first attempt.

He rubbed his eyes and lay there listening to the sounds of vehicles down on Gorky Street. It was almost eight, but he felt reluctant to get up. 13

His mind went back to the previous day. The funeral, the huge crowds, a city close to bursting with incoherent emotions.

Ströhm was still trying to make sense of his own feelings. Like almost everyone else he had found himself weeping when the coffin was lowered into the mausoleum. The sense of loss was immense, overpowering, and the fact that it also seemed ludicrous made no difference at all. Like the old Bolsheviks brought to trial in the thirties, despite all they knew and guessed, they all shared a mad yearning to believe. They knew the size of the hole Stalin had left, and maybe they’d been weeping because deep down they knew that neither filling that hole nor failing to do so would make things any better. For both better and worse, Stalin was irreplaceable.

And here they all were, stuck on this tragic ship, which had sailed with such great intentions, but which now, despite all denials, was not only utterly lost but lacking any compass or map. In circumstances such as these, what could even the best–intentioned new helmsman do?

He shook his head, hoping to shake out the pessimism, and went to run a bath. At least the water was hot at the National—a Greek comrade he had spoken to the previous day had lamented the lack of such at the Metropol. And the shortage of pillows.

Ten minutes later Ströhm was on his way down to breakfast. Sequestered in one corner of the ornate dining room like a gang busy planning a robbery, the leaders of the SED—the East German Socialist Unity Party—were already well into breakfast, sifting through the slices of dubious cold meat. Herrnstadt and Zaisser nodded welcomes, but Ulbricht and Grotwöhl ignored him. As expected, all his colleagues looked fresher than he did, which, considering their levels of consumption the night before, said a lot about what they were used to. People said that living in Karlshorst—the Berlin suburb where the Soviets had planted their conqueror’s colony—was just like living in Russia, and its 14privileged German occupants had certainly adopted the drinking culture.

Ströhm spread some toast with Georgian cherry jam and looked around the room. Though undoubtedly elegant, it reeked of the past. There was nothing modern about Moscow, the only things pointing you towards the future were the idealised workers on their huge billboards. The Revolution was living in the past. Literally so.

He found himself wishing he was back in his Friedrichshain apartment with Annaliese, Markus, and Insa. Then again, if it hadn’t been for them, he probably wouldn’t have been here in Moscow, because over the last five years his wife and children had been his only persistent source of hope. Just by being there, they had provided the strength and reasons he needed to keep on trying; left to his own devices he might have just given up.

It was 7:30 a.m. in Berlin, and he could picture the scene there, Annaliese fussing around as she made sure that Markus and Insa had all they needed for their day at the Party crèche, before dropping them off and walking across to the State Hospital and her job as a ward sister.

“What are you smiling at?” Ulbricht asked him out of the blue, as if the buried Stalin was still quite capable of detecting one man’s lack of respect.

“I was thinking how enormous the crowds were yesterday,” Ströhm said innocently. “Few leaders could expect such an outpouring of love when they die.”

“True,” Ulbricht said curtly, and Ströhm saw Herrnstadt repress a smile. All of them knew there’d be dancing in the street if Ulbricht dropped dead.

Half an hour later they were all on a bus, heading out through the city to visit a collective farm. Ströhm suspected that the trip had been arranged to keep them occupied ahead of the Soviet-satellite meetings that afternoon, and in such a way that the different 15delegations were kept apart, allowing them no chance to gang up on their mutual masters. With the Bolshoi shut until evening, a collective farm or model factory were the only obvious options.

If the view from the window was any guide, the route had not been chosen with a desire to impress—Moscow’s suburbs and the surrounding countryside still looked desperately poor. Ströhm suspected that the “tourists”—those foreign delegations who were not yet in power—would be seeing Russia’s better side, and why not? Why not let them keep their illusions if it made them more determined to succeed at home? So few in the West had any idea how much the Soviet Union had lost in the war, so why gift them a true picture of how long the recovery was taking?

Despite being under several inches of snow, the collective farm did look clean, efficient, and well-organised. Tractors gleamed and peasants smiled, the latter keen to explain how their life had been transformed. There was a table replete with snacks, and, God forbid, tumblers of vodka. Ströhm hadn’t yet seen one of the new collective farms back home, but those who had were given to sadly shaking their heads.

The return drive through a picturesque snow shower was pleasant, but for Ulbricht’s snoring in the front seat, which gave the bus’s groaning engine a run for its money. Ströhm fantasised about enlisting the others to carry their leader off the bus and dump him in a snowdrift.

Back in the city, another meal was waiting, and that was barely finished when the limousine arrived to carry four of them—Herrnstadt, as the editor of the Party’s paper Neues Deutschland, was meeting with his Soviet counterparts—the short distance to the Kremlin. Once inside they found themselves in a queue of delegations, each parked in a room off a long corridor, and periodically shuffled forward like a game of musical chairs. Their own appointment was for 2:30 p.m., but it soon became apparent that the wait would last several hours. 16

They went through their briefing notes, but not with any sense that they needed to. The four of them were there to listen, not to put forward ideas of their own. Any speaking would be purely reactive and would probably involve explaining why last time’s instructions had not been followed with either more rigour or more flexibility.

Ströhm set about putting himself in a positive frame of mind. He told himself that was the least he could do, given that his country’s future was at stake. He told himself that he needed to give the Soviets more credit, to recognise their real achievements made over the last eight years, despite the devastation wrought by his own countrymen in the war. Almost everywhere west of the Volga they’d more or less had to start from scratch, rebuilding the factories, the dams, the cities they’d raised with such titanic effort before the war. Economically, they’d had an impossible job, and yet they’d somehow made a fist of it. Credit where credit was due.

Politically … well, that was a different matter. He could see that there’d been no real alternative to “the Party knows best”—a planned economy was bound to inhibit free discussion. And the Party often had known best. What democratic government would or could have taken a snap decision to move industries employing thousands of people five hundred miles to the east, out of reach of Hitler’s tanks? And it was not as if the Party was trampling on a democratic tradition. It was still, in Ströhm’s most wishful thoughts, trying to make one possible.

But he was not a Russian. The CPSU might know best when it came to the Soviet Union, but he had never believed it knew best when it came to Germany. For almost a decade Moscow’s stooges—himself included—had wielded some sort of power in eastern Germany, but only at the discretion of the Soviets. And in that time things had slowly gone from bad to worse. Bringing communism to eastern Germany had always been 17a near-impossible task after the Red Army had raped its way through Berlin, and that was the start. It wasn’t long before looting the country for reparations and creating “necessary sacrifices” like the lethal Wismut uranium facility had turned widespread resentment into utter loathing.

The easiest option was to tell yourself there was nothing you could really do, and just enjoy the not inconsiderable perks. Many had taken that path, but not all. There were still those like himself, at all levels of the Party, who were prepared to try to make the best of what would probably be a once-in-a-lifetime shot at fulfilling their political dreams. But there weren’t that many of them anymore, and with each new shortage, each new stink of corruption, there were fewer people prepared to give them a hearing.

Maybe Stalin’s death would loosen things up and give the different national parties the chance to try different ways. Ströhm wasn’t privy to what went on in the minds of the Soviet leaders, but the noises they were making seemed encouraging, and he would love to believe that over the next few months some transformative vision would emerge from a new collective leadership.

Or not. For the moment, here they all were, queuing up to receive their marks for recent performance. A gold star for some, black marks for others. A grudging “could do better” for the Poles, an acerbic “last chance to pull up your socks” for the Hungarians.

Ströhm sighed and stared at the obligatory portraits of Lenin and Stalin. Lenin had made mistakes, but Ströhm still liked to think he’d been a decent man. It was hard to think that about Stalin. A necessary one, perhaps, but necessary to whom? And for what?

It was almost five before they were finally ushered into the seat of power, a nondescript committee room almost entirely filled by a long table and its dozen chairs. The air was full of smoke, and it 18took Ströhm a few seconds to identify Georgy Malenkov, Lavrenti Beria, Nikolai Bulganin, and Nikita Khrushchev sitting in a row on the far side of the table. Molotov, they were told, was ill. Ströhm had met Malenkov and Bulganin on several occasions, Beria on only a few, which had suited him just fine. The man gave him the creeps. He had never met Khrushchev but had heard he was blunt to the point of rudeness, and a good deal smarter than he liked to appear.

There was no sign of a stenographer, but the room was presumably equipped with hidden recording devices.

The DDR delegation took up the facing seats, Ulbricht and Grötewohl flanked by Zaisser and Ströhm, who, as the SED Central Committee’s liaison with its CPSU equivalent, was the most junior member of the delegation.

The “discussion” lasted about twenty-five minutes, which seemed rather short when the future of German socialism was at stake, but at least it offered some hope. Malenkov did most of the talking, occasionally deferring to Nikolai Bulganin on matters of detail. Khrushchev looked vaguely belligerent, Beria slightly amused, but neither said much. The gist of the CPSU’s general “advice,” as gradually became apparent, was for the SED to take its foot off the accelerator pedal. “Across the board,” Beria insisted, mixing metaphors.

Whether this “advice” constituted a real change of direction on the new Soviet leadership’s part, or just a pause to consider the alternatives to the current orthodoxy, was not clear to Ströhm. Or, he suspected, to the Soviets themselves.

There was one specific instruction. The previous year, the principal border between West Germany and the DDR had been hardened, making it almost impossible for would-be emigrants to cross. This had predictably funnelled those who wanted out towards the only border left open, the one between the Soviet and Allied sectors in Berlin. So Ulbricht had asked the Soviets if they 19could close that border too, and a couple of months before Stalin’s death they had given their provisional approval. Which they were now rescinding. The outflow of skills and talent would continue.

The Germans had their orders.

The limousine was gone, leaving the four of them to trudge back across Red Square and down the slope to the National. Nobody said a word, but Ulbricht and Grötewohl looked the most unhappy, which probably had to be good news.

There were still four hours before their night train left from the Belorussian Station, and Ströhm was pleased to find his Soviet counterpart Oleg Mironov waiting in the lobby. Mironov spent most of his time in Karlshorst, ostensibly attached to one of the Soviet intelligence apparats, and the two of them had met regularly since Ströhm had secured his current position. A guarded friendship had gradually formed as the two men discovered they harboured not dissimilar hopes for the future.

“Let’s take a walk,” Mironov suggested, and Ströhm readily accepted. “The river, I think,” the Russian decided, once they were back on the sidewalk. “My father used to say that times of change were times to take shelter,” Mironov remarked, “but the open air seems safer to me. Not that I’m planning to reveal any secrets,” he added with a smile.

“And is this a time of change?” Ströhm asked, staring up at the Kremlin wall to his right.

“Oh I think so. It has to be. I mean some things are going well—everyone knows we’ll soon have a hydrogen bomb—but the problems are mounting, particularly in the satellites. I rather suspect that Rudolf Slánský will be the first of many.”

The Czech party leader, having lost favour with both the Soviets and his own Politburo, had been tortured into making a transparently false confession and hanged the previous December. “Ulbricht?” Ströhm asked. 20

“I’d say he’s on borrowed time. He’s too rigid, too stuck in the past. He learnt all his tricks under Stalin, and I doubt he could learn any new ones.”

Saint Basil’s Cathedral was behind them now, the river a hundred yards ahead. “How is your father?” Ströhm asked, thinking it politic to change the subject.

“Mmm. I went to see him a few days ago. He’s cantankerous as ever, and getting a bit funny in the head, I think. He is almost eighty, so it’s not surprising, but if he does go completely gaga, I’m a bit apprehensive about what he might come out with.”

“Orlaya didn’t make the trip?”

“No. My wife prefers Karlhorst.” Mironov grimaced. “I can never wait to get back home myself,” he added. “I’ll miss you, of course,” he added with a grin. “But there’s something corrosive about lording it up in someone else’s country. No matter how well-intentioned you might be.”

Ströhm let that go. “Do you think your new leadership will solve a few problems?” he asked.

“Who knows? I wouldn’t be in their shoes. I mean, it’s all so devilishly difficult. Our economy is almost sclerotic—the heart keeps pumping, but there’s too many blocked arteries. We can’t get rid of them because they’re intrinsic to any integrated planning system, but if we don’t find a way to get around or through them the blood will just stop flowing. It already has in some sectors. We’ve done wonders with steel and construction and power, but agriculture is a total mess. And people have more sophisticated wants than they used to. Our soldiers in Berlin—forgive me for bringing them up, but while they were doing terrible things to your women they were inside thousands of houses, and they saw how Germans lived, all the things they had. It was like a storybook to them, and when they came home they spread the story. We’re proud that we can match the West in technology and culture, but until we can get rid of food 21queues and turn out a decent washing machine for every Soviet family, we’ll never get people to believe that the future is ours.”

Remembering how pleased Annaliese had been with hers, Ströhm could hardly disagree.

“This year’s going to be a real rollercoaster ride,” Mironov went on, with almost indecent enthusiasm. He looked around, making sure their stretch of towpath was empty. “Stalin’s gone. And yes, there are feelings of sadness and loss. But there’s also a sense of relief—haven’t you felt it?”

“I have.”

“And relief comes with expectations. The new leadership is going to have to do something different. They can’t shut the doors any tighter, so they’ll have to open them up. The tricky part is knowing by how much—open them too wide and everything will fall apart. Another thing my dad once said to me: the hardest thing to do in a heavy wind is keep a door half-open.” He looked at Ströhm. “And that’s exactly what we have to do.”

THE MEETING BROKE UP, THE final final changes having been inserted in the script. They would run through it on the sound stage next morning, whereupon the star Eddie Franklin would doubtless insist on those few last-minute revisions he always dubbed “the final nails.”

If, unlike some of her fellow cast-members, Effi Koenen had experienced little difficulty in making the leap from radio to TV, that was probably because her experience as an actor in pre- and postwar Germany had been so wide. She had done everything from burlesque to movies, from live theatre to musicals. When she had worked on the radio incarnation of Please, Dad, she’d been known for acting at the mike rather than simply speaking her lines, not because she wanted to impress anyone, but because that was what live theatre had taught her to do. Having also made twenty-plus films, she 22understood why actors who’d only worked in that medium found it hard to get things right in the very limited number of takes a live studio recording allowed.

Effi knew she was good in the part, but whether the part was making the best of her talents wasn’t so clear. Housekeeper Anna—“Mrs. Luddwitz”—with her no-nonsense willingness to say what she felt in any given situation, was a role she could probably play in her sleep. But working on the show was enjoyable, and though she found its star somewhat lacking as a human being, she had to admit he made a good comedy foil. And the two children they’d brought in for the TV series were an absolute delight. Effi had expected a pair of spoilt Hollywood brats, like the two who’d been in the radio show, and who, much to everyone’s relief, had been deemed to look too old when the television version was first considered.

“You happy with it?” Beth Sharman asked, falling into step beside her.

The thirty-ish writer had joined the two who worked on the radio version when the TV series was given the go-ahead and was now Effi’s best friend on the set. “One of your best, I think.”

“We’ll be up there with Lucy yet.” I Love Lucy, which was made in the same studio, had conquered America over the past eighteen months. Lucy herself had even sent McCarthy packing the previous September.

“Sorry to burst your bubble,” Effi said, pleased with her use of the English phrase. After three years in America she was virtually fluent, and her normal slight German accent was less noticeable than the one she put on for Mrs. Luddwitz, but there were always stray new phrases to learn. “Lucy and Desi are timeless,” she told Beth. “You’ve heard of Everyman? Well, they’re Every-Marriage. They could spin it out forever. Whereas our little set-up is too specific for global conquest.” 23

“You’re probably right. We’re doing okay, though.”

They had reached the outside world, which looked as grey as it had that morning.

“Are you going straight home?” Beth asked.

“I’m picking Rosa up from school in an hour or so. Would you like to get a coffee somewhere? Or even a drink.”

“Now you’re talking.”

Effi’s car was fortuitously placed on the end of a row—getting in and out of parking spaces had never been a forte. She’d been driving on and off for more than a decade but still didn’t like it that much. LA was better than Berlin—the streets were wider, the drivers mostly slower, and her car had automatic transmission—but she only drove when she needed to, never for pleasure. “Where shall we go?” she asked, once they were side by side on the Buick’s bench seat.

“How about the Blue Angel?”

“Good choice.”

The mile drive passed without incident. Effi liked the bar on Fairfax for two reasons. One was the palm-filled garden at the back, which today lacked the sunlight it needed; the other was an unusually wide selection of German wines, which a then-doting patron had introduced when Von Stroheim and Dietrich teamed up in Hollywood more than twenty years before.

The bar was almost empty ahead of the post-work rush. “A glass of Riesling, please,” Effi answered Beth’s query. The writer ordered herself a Manhattan, and the two of them took a table overlooking the garden of sun-hungry palms, their fronds swaying in the breeze.

“You ever smoke?” Beth asked, lighting one of their sponsor’s products.

“Only in movies. The first time I was asked to, I coughed so much the audience would have thought I had consumption. I was playing a woman with two sons in the Hitlerjugend—the 24Hitler Youth—and they thought I should have habits the boys could disapprove of. Standard Goebbels fare.”

Beth laughed, but then grew serious. “I’ve been wanting to ask. Didn’t that bother you? Tell me to mind my own business if you want to.”

Effi took a sip of wine to consider. “At the time? Not really. Not at first, anyway. The films were such obvious propaganda that few of us were able to take them seriously. Later, yes, some regrets. When I agreed to take one role, John and I had one of our few real falling-outs. He was right—I should have turned it down—but then he was making the same compromises as a journalist that I was as an actor. They were difficult times, and we quickly got over it. I don’t say this as an excuse, but I think it’s hard for Americans to imagine what it was like in Germany then. You dared to put up a fight, and that was the last your friends might see of you. People just disappeared, and the next thing you knew they’d died in a camp. Always of pneumonia, though by the time they told you that the body was already burnt or buried.” She looked out of the window. “Seems unreal here, doesn’t it. And of course it is. It wasn’t like HUAC putting you on a blacklist and stopping you from working. I know that’s terrible, but at least no one dies. Or hardly anyone,” she added, thinking of Mady Christians, the Austrian actress whose early death from a cerebral haemorrhage had followed relentless Committee harassment.

Beth made a face. “You’re right that few people die, but any sense of national sanity might. HUAC often feels like a bad joke—I mean, I keep asking myself who could actually believe this shit. But they do, and it keeps getting closer to home.”

“Laura?” Effi asked. Laura Fullagar played the housekeeper next door, whose over-the-fence conversations with Mrs. Luddwitz produced some of the show’s better moments.

Beth sighed. “There are rumours. Believable ones. She makes no secret of what she thinks of McCarthy.” 25

“Neither do you. Neither do I.”

“But I was never a party member and couldn’t give them a single name of anyone who was. I’m assuming—hoping—that you could say the same.”

“I was never in a party, full stop. I wasn’t interested in politics. John was in the KPD—the German communist party—in the twenties, but he left long before I met him. I certainly couldn’t tell HUAC anything, but then I wouldn’t if I could.”

“Easy to say.”

“I suppose so,” Effi conceded. And easier if you were forty-four and other things were now more important than your career, she thought. “Are you certain that Laura was in the Party?”

“No, but I’d be surprised if she wasn’t. Before the war she was very close to Dick Moran, and he was named in the Red Channels pamphlet.”

“Hell.”

Beth drained her glass. “It’s like some terrible disease,” she said. “You know it’s around, and you know that some people are going to catch it, and you just hope it won’t be you or one of your friends.”

“And on that note,” Effi said, checking her watch, “I’d better be going. Can I drop you anywhere?”

“No, thanks. I think I’ll walk over to Crossroads of the World and buy some new clothes while I still have a salary. I’ll see you tomorrow,” she said, as they reached the car.

Effi drove up Fairfax and took a right onto Santa Monica Boulevard. Rosa’s school was about two miles from their rented house on Melrose, and often she chose to walk, but Effi was pleased when she didn’t. Almost seventeen, her adoptive daughter would soon be of an age to strike out on her own, and Effi was keen to make every moment count.

Driving alone she found it easier to concentrate, which according to John was proof of an open heart. When they’d first come to 26LA, expecting only to stay a few months, she and John had hired a governess-type woman to keep up Rosa’s education, but once it was clear that they’d be there for at least a year, a place had been found for the girl in one of the Hollywood schools which mostly catered for the children of the town’s entertainment industry. Serving such a rich clientele, these schools all had good teachers and facilities, but this particular institution came with the added attraction of an enthusiastic arts mistress. Given Rosa’s proclivity for turning the world into drawings, this was more or less essential.

Effi was early—these days she almost always was. After decades of others complaining about her lack of punctuality, she seemed to have gone to the other extreme. As everyone said, there was nothing like children for turning your life upside-down.

Rosa had found school a bit difficult at first, but then adapted faster than Effi had dared to hope for. Her English had improved dramatically, and was now as good, if not better, than Effi’s—Russell sometimes joked she spoke his own language better than he did after thirty years in Germany. She made a few friends, and if most of them seemed to be fellow outsiders, then that was probably not unusual for a school in Tinseltown. Her artistic talents, already formidable, only grew more extraordinary, and when the art teacher left to have a family, Rosa discovered an evening class which seemed, unusually for LA, to welcome people from all parts of the city’s diverse population. Perhaps living under Hitler had made Effi more sensitive to racial prejudice than most, but LA left a lot to be desired in that department, and in odd moments Effi had found herself reminded of Berlin during the Nazis’ first few years in power. Rosa’s instincts, she thought, were much the same—her latest interest was Negro music, which white Americans called “race music,” as if they’d been spared the burden of belonging to one themselves.

Rosa, Effi thought, was all right. Despite a personal history distressing enough to break most children, she had exceeded all 27her parents’ expectations. She was kind and clever and immensely talented. She had always seemed at ease with herself and was increasingly at ease with others. Rosa was fine, Effi told herself again. It was John she should be worrying about.

He had enjoyed the novelty of their first year in Hollywood, and endured the second because he thought it would be the last. But then both she and Rosa had prospered, Effi professionally and their daughter as a person, and John had put their interests above his own. She had loved him for that but was enough of a realist to know that there might be a price. These last few months she’d been reminded of the last winter before the war, when he’d been reduced to writing about pets and postage stamps as Europe slowly caught fire.

That hadn’t ended well. Ten years of ad hoc espionage, of playing Russian Roulette with Nazis, Brits, Americans and, of course, the Soviets. He needed to be reporting on—or at least writing about—things that interested and concerned him. Something he could get his teeth into. Given that the conditions of his residency forbade him from taking paid employment here in the US, that wouldn’t be easy. But surely not impossible. She should be encouraging him to get on with the book he’d already been commissioned to write, before some young disciple of Shchepkin’s waylaid him in a bar with a new siren song he couldn’t resist.

A bell was ringing inside the school, and only a few seconds had passed when the kids began flooding out. Rosa appeared after several minutes, walking alone, looking out for the car. She waved and smiled when she saw it, and patiently waited for a gap in the traffic to cross the street.

Several friends had remarked how much Rosa resembled Effi, some of them knowing the girl was adopted, others not. It was true that they shared a similar mouth and colouring and were both raven-haired and slimly built. But Rosa’s eyes were darker, and her movements less graceful than Effi’s—it was as if, in John’s 28words, a lack of physical fluidity was the price she was still paying for her survival.

“Hi, Mom,” she said in an exaggerated American accent as she climbed into the car.

“Oh, pulleeez!” Effi retorted with a grin.

“Are we going straight home?” Rosa asked in her normal voice.

“That was the plan. I was actually going to cook.”

Rosa made a face. “Cook what? Couldn’t we go out for Chinese?”

The idea was not unwelcome. And John would be happy. “I suppose so,” she said. “But we can’t eat out all the time.”

“Why not? If we can’t afford it, who can?”

“It’s not good for us?” Effi said automatically. She was sure it wasn’t, though she wasn’t sure why. She remembered John’s ex-brother-in-law, Thomas, telling his daughter, Charlotte, that people should learn how to look after themselves before they let others do it for them. It had been over a Sunday lunch in Dahlem before the war, and Lotte was well into her twenties by now. Effi wondered if she enjoyed cooking.

They found John already at home, making the most of a late emerging sun on their back porch. Like half of Hollywood he was reading John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, but unlike most he was less than impressed. “All the characters are either pure evil or close to perfect,” he had said when Effi asked him how he was finding it. “Does that sound realistic? And after three hundred pages I still haven’t met anyone with a black face. Does that sound like America?”

“It sounds like Melrose Avenue,” Rosa said pointedly.

“Touché,” Russell conceded with a grin. “How was school?”

“Mostly boring.”

“We were thinking Chinese,” Effi interjected.

“Never a bad idea,” Russell agreed. “Are we driving to Chinatown or walking round to Wong’s?” 29

“A walk will do us good.”

“Okay.”

It was getting dark by the time they arrived at the restaurant, streaks of orange in a still-cloudy western sky. The food at Wong’s was not the best, but it was good enough, and the staff were friendly. They ordered most of their usual dishes, plus the obligatory new one that Rosa insisted on. The eggplant concoction she picked that evening was better than many previous choices.

“So how was Stephen Brabason?” Effi asked as they walked slowly back. Rosa as usual was walking slightly ahead of them, looking this way and that like a reconnaissance scout.

“Nicer than I expected,” Russell said. “Pity he’s such a hopeless actor.”

“Eddie Franklin’s opposite,” Effi remarked.

“Is he giving you trouble?”

“No, not really. But we—the show—may have a problem.” Switching into German, she repeated what Beth had told her about Laura Fullagar.

“That’s a shame,” Russell said, following her lead. “For her and the show. She’s good.”

“Yes. And she has a child to support on her own. Her husband was killed in the war.”

Rosa had dropped back alongside them. “I really don’t get it,” she said. “What are they all so upset about? Do they think there’s some dark plot to destroy the American way of life? Or are they expecting the Russians to sweep across the ocean and turn them into slaves? I mean, really. How stupid can they be?”

“They are,” Effi said.

“What they’re upset about—the people funding and running this scare campaign—is the prospect of losing markets in Europe and Asia,” Russell said. “Which they will rightly see as a curb on their freedom, and wrongly claim is a curb on everyone else’s.” 30

“That does make more sense,” Rosa said thoughtfully.

But not something you should say in school, Effi stopped herself from saying. Rosa was usually as uninterested in politics as her own younger self had been, and Effi was pleased to see this wasn’t from lack of caring.

“The land of the free,” Russell noted wryly. “It’s probably a good thing I can’t work here. At least they can’t take my job away.”

Effi squeezed his arm. “Speaking of work, how is your book research going?”

EIGHT WEEKS LATER

Several Dead in Plovdiv

T