5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Old Street Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

In July 1939 Russell returns to Berlin as the newly-appointed Central European correspondent of an American newspaper. With his communist past, German son and English-American parentage he's the perfect catch for any of Europe's warring espionage services, and none will take no for an answer. Through the long Berlin summer, through trips to Prague, Warsaw and Moscow tracking Europe s descent into war, Russell seeks to satisfy his secret masters, protect his girlfriend Effi and his son Paul, and retain some sense of his fragile integrity. And if this wasn't difficult enough, a friend needs his help in finding the missing Jewish niece of an employee. With a whole continent headed for self-immolation, saving just one person shouldn t be so difficult...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

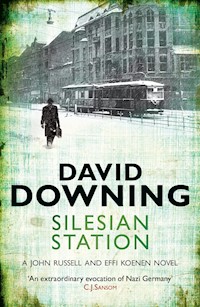

Silesian Station

David Downing

For Nancy

Contents

Title PageDedicationA safer lifeInto the cageA leap in the lightRehearsalsThe Ostrava freightLeafleteersSilesian angelsThe wave of the pastJewish ballastRuinsPraiseCopyright

A safer life

Miriam Rosenfeld placed the family suitcase on the overhead rack, lowered the carriage window and leaned out. Her mother’s feelings were, as ever, under control, but her father was visibly close to tears.

‘I’ll visit as soon as I can,’ she reassured him, drawing a rueful smile.

‘Just take care of yourself,’ he said. ‘And listen to your uncle.’

‘Of course I will,’ she said, as the train jerked into motion. Her mother raised a hand in farewell and turned away; her father stood gazing after her, a shrinking figure beneath the station’s wooden canopy. She kept looking until the station had been dwarfed by the distant mountains and the wide blue sky.

Her great-grandfather had come to this part of Silesia almost sixty years earlier, driven west by pogroms in his native Ukraine. He had been a successful carpenter in a small steppe town, and his savings had bought the farm which her parents still owned and worked. Seduced by the vista of looming mountains, his had been the first Jewish family to settle within ten miles of Wartha. Mountains, he’d told his son, offered hope of escape. The Cossacks didn’t like mountains.

Miriam dried her eyes with the lace handkerchief her mother had insisted she take, and imagined her parents riding back to the farm, old Bruno hauling the cart down the long straight track between the poplars, the dust rising behind them all in the balmy air. It had been a wonderful summer so far, the crops ripening at an amazing speed.

Her father would need extra help now that she was gone, but where would they get it? Other westward-bound Jews had been less obsessed by memories of the Cossacks, more interested in the joys of city life. The Rosenfelds were still the only Jewish family in the area, and hiring non-Jewish help was no longer allowed.

Her father’s younger brother Benjamin had hated life in the countryside from an early age. He had left for Breslau when he was fifteen, but even Silesia’s capital had proved insufficiently exciting, and after two years in the trenches Benjamin had settled in Berlin. During the 1920s he’d had a bewildering variety of jobs, but for the last six years he had worked in a printing factory, earning enough money to buy smart clothes and the exciting presents which distinguished his yearly visits. He had seemed less self-satisfied on his last visit, though. His own job was secure enough, he said, but many other Berlin Jews – most of them, in fact – were not so fortunate.

For those whose world barely stretched as far as Breslau, some of Uncle Benjamin’s stories were hard to take in. The Rosenfelds had never married non-Jews, but they were not particularly religious, and kept the Jewish traditions that they followed very much to themselves. Miriam’s father had always been well-liked by neighbouring farmers and the merchants he did business with, and it had come as something of a shock the previous year when the local government inspector, an old friend of the family, told them about new regulations which only applied to Jewish-owned farms. On a later visit he had given them a blow-by-blow account of events in Breslau during the first week of November – two synagogues burned, seven Jews killed. He wanted them to know that he was talking as a friend, but perhaps they should think about emigration.

They thanked him for his concern, but the idea seemed preposterous. A depressing letter from Benjamin detailing similar events in Berlin gave them momentary cause for concern, but no more than that. Benjamin wasn’t talking about emigrating, after all. And how could they sell the farm? Where would they go?

Life on the farm went on in the usual way, up with the light, at the mercy of the seasons. But beyond its boundaries, in the village and in Wartha, it was slowly becoming clearer that something important had changed. The younger men – boys, really – not only lacked the civility of their parents, but seemed to delight in rudeness for rudeness’s sake. They were only children, Miriam’s father claimed; they would surely grow up. Her mother doubted it.

Then a group of boys on their way back from a Hitler Youth meeting intercepted Miriam on her way home from the village shop. She wasn’t frightened at first – she’d been at school with most of them – but the mockery soon turned to filth, their eyes grew hungry and their hands started tugging at her hair and her sleeves and her skirt. It was only the sudden appearance of one boy’s father that broke the spell and sent them laughing on their way. She hadn’t wanted to tell her parents, but one sleeve was torn and she’d burst into tears and her mother had dragged the story out of her. Her father had wanted to confront the boys’ parents, but her mother had talked him out of it. Miriam heard them arguing late into the night, and the following day they announced that they were writing to ask Uncle Benjamin about finding her a job in Berlin. Things might be bad there, but at least she’d be with other Jews. There was always strength in numbers.

She hated the idea of leaving, but no amount of pleading would change their minds. And as the days went by she noticed, almost reluctantly, the depth of her own curiosity. She had never been further than Breslau in her seventeen years, and had only been there on the one occasion. The massive square and the beautiful town hall, the masses of people, had left her gasping with astonishment. And Berlin, of course, was much, much bigger. When Torsten had taken her to the cinema in Glatz she’d seen glimpses of the capital in a newsreel, the huge stone buildings, the fields for just walking in, the swerving automobiles and gliding trams.

Uncle Benjamin eventually replied, sounding doubtful but promising work at the printing factory. The date was set. Today’s date.

Away to the south, the line of mountains was growing dimmer in the heathaze. She took a deep gulp of the familiar air, as if it were possible to take it with her. A new life, she told herself. A safer life.

The train clattered purposefully on. The fields grew larger as the land flattened out, lone trees and small copses stationed among them. Red-roofed villages with solitary church spires appeared at regular intervals. A black and white cat padded along between rows of cabbages.

It was really hot now, the sun pulsing down from a cloudless sky. The platform at Münsterberg seemed almost crowded, and two middle-aged women took the corridor seats in Miriam’s compartment, acknowledging her greeting but ignoring her thereafter. At Strehlen the sounds of a distant marching band could be heard, and the station seemed full of uniformed young men. Several took up position in the corridor of her coach, smoking, laughing and talking at the top of their voices, as if the world deserved to hear what they were saying. Two older men – businessmen by the look of them – took the seats opposite and next to Miriam. They raised their hats to her and the other women before they sat down. The one at her side had eaten onions for lunch.

Half an hour later they were rolling into Breslau, dirt tracks giving way to metalled roads, small houses to factories. Other railway lines slid alongside, like braids intertwining on a thickening rope, until the train rattled its way into the vast shed of glass and steel which she remembered from her first visit. The onion-eater insisted on getting her suitcase down, joked that his wife’s was always a great deal heavier, and tipped his hat in farewell.

Torsten’s face appeared in the window, with its usual nervous smile. She hadn’t seen him since he’d taken the job in Breslau but he looked much the same – unruly hair, crumpled clothes and apologetic air. The sole children of neighbouring farms, they had known each other since infancy without ever being close friends. Their two fathers had arranged for Torsten to ensure that no harm befell her between trains.

He insisted on taking her suitcase. ‘Your train’s in an hour,’ he said. ‘Platform 4, but we can go outside and get some lunch and talk.’

‘I need the ladies’ room,’ she told him.

‘Ah.’ He led her down steps and along the tunnel to the glass-canopied concourse. ‘Over there,’ he said, pointing. ‘I’ll look after your suitcase.’

A woman at one of the wash-basins gave her a strange look, but said nothing. Outside again, she noticed a nice-looking café and decided to spend some of her money on buying Torsten coffee and cake.

‘No, we must go outside,’ he said, looking more than usually embarrassed. It was then that she noticed the ‘Jews not welcome’ sign by the door. Had there been one by the ladies’ room, she wondered.

They walked back down the tunnel and out into the sunshine. Several stalls by the entrance were selling snacks and drinks, and across the road, in front of a large and very impressive stone building, there was an open space with trees and seats. As Torsten bought them sandwiches and drinks she watched a couple of automobiles go by, marvelling at the expressions of ease on the drivers’ faces.

‘It’s better outside,’ she said, once they’d chosen a seat in the shade. The large stone building had Reichsbahn Direktion engraved in its stone facade. High above the colonnaded entrance a line of six statues stared out across the city. How had they gotten them up there, she wondered.

‘Is it all right?’ Torsten asked, meaning the sandwich.

‘Lovely.’ She turned towards him. ‘How are you? How’s your new job?’

He told her about the store he worked in, his boss, the long hours, his prospects. ‘Of course, if there’s a war everything will have to wait. If I survive, that is.’

‘There won’t be a war, will there?’

‘Maybe not. My floor boss thinks there will. But that may be wishful thinking – he comes from Kattowitz, and he’s hoping we can get it back from the Poles. I don’t know.’ He smiled at her. ‘But you’ll be safe in Berlin, I should think. How long will you be there for?’

She shrugged. ‘I don’t know.’ She considered telling him about the incident with the boys, but decided she didn’t want to.

‘Could I write to you?’ he asked.

‘If you want to,’ she said, somewhat surprised.

‘You’ll have to send me your address.’

‘I’ll need yours then.’

‘Oh. I don’t have a pencil. Just send it to the farm. They can send it on.’

‘All right,’ she said. He was a sweet boy, really. It was a pity he wasn’t Jewish.

‘It’s nearly time,’ he said. ‘Have you got food for the journey? It’s seven hours, you know.’

‘Bread and cheese. I won’t starve. And my father said I could get something to drink in the restaurant car.’

‘I’ll get you another lemonade,’ he said. ‘Just in case there’s nothing on the train.’

They reached the platform just as the empty train pulled in. ‘I’ll get you a seat,’ Torsten shouted over his shoulder as he joined the scrum by the end doors. She followed him aboard, and found he’d secured her a window seat in a no smoking compartment. Other passengers already occupied the other three corner-seats. ‘I’d better get off,’ he said, and a sudden pang of fear assaulted her. This was it. Now she really was heading into the unknown.

He took her hand briefly in his, uncertain whether to shake or simply hold it. ‘Your uncle is meeting you?’ he asked, catching her moment of doubt.

‘Oh yes.’

‘Then you’ll be fine.’ He grinned. ‘Maybe I’ll see you in Berlin sometime.’

The thought of the two of them together in the big city made her laugh. ‘Maybe,’ she said.

‘I’d better get off,’ he said again.

‘Yes. Thanks for meeting me.’ She watched him disappear down the corridor, reappear on the platform. The train began to move. She stretched her neck for a last look and wave, then sat back to watch Breslau go by. The rope of tracks unwound until only theirs was left, and the buildings abruptly gave way to open fields. Farms dotted the plain, so many of them, so big a world. A few minutes later the iron lattice of a girder bridge suddenly filled the window, making her jump, and the train rumbled across the biggest river she had ever seen. A line of soldiers were trotting two-by-two along the far bank, packs on their backs.

Cinders were drifting in through the toplight, and the man opposite reached up to close it, cutting off the breeze. She felt like protesting but didn’t dare. The compartment seemed to grow more stifling by the minute, and she found her eyes were closing with tiredness – anxiety and excitement had kept her awake for most of the previous night.

She woke with a start as the train eased out of Liegnitz Station, and checked the time on her father’s fob watch. It was still only three o’clock. She’d tried to refuse the loan of the watch, but he had insisted that the sun and the parlour clock were all he really needed. And she could always send the watch back when she’d bought herself one of those smart new ones that people wore on their wrists.

Fields and farms still filled the windows. Two of her fellow passengers were asleep, one with his mouth wide open. He suddenly snorted himself awake, eyes opening with annoyance, then closing again.

Feeling thirsty, she reached for the bottle Torsten had bought her. She felt stiff after her sleep, and the sight of a man walking past the compartment encouraged her. She would look for the restaurant car, and buy herself a cup of tea.

A young soldier standing in the corridor told her the restaurant car was three carriages ahead. The train seemed to be going faster now, and as she walked along the swaying corridors she felt a wonderful sense of exhilaration.

The restaurant car had seats either side of a central gangway, booths for two on the right, booths for four on the left. She took the first empty two-seater and examined the menu. Tea was thirty pfennigs, which seemed expensive, but a cup of coffee was fifty.

‘A cup of tea, please,’ she told the young man who came to take her order.

‘No cake, then?’ he asked with a grin.

‘No thank you,’ she said, smiling back.

As he walked away she noticed a woman in one of the four-seaters staring at her. She said something to the man facing her, and he turned to stare at Miriam. The woman said something else and the man got up and walked off in the direction her waiter had taken. A minute or so later he returned with a different waiter, a much older man with a bald head and bristling moustaches. The set of his mouth suggested an unwelcome task.

He came over to Miriam’s table and lowered his head to talk to her. ‘Excuse me, miss,’ he said, ‘but I need to see your identity papers.’

‘Of course,’ she said. She pulled them out of her shoulder bag and handed them over.

He scanned them and sighed. ‘I’m sorry, miss, but we’re not allowed to serve Jewish people. A law was passed last year. I’m sorry,’ he said again, his voice dropping still further. ‘Normally, I wouldn’t give a damn, but the gentleman back there has complained, so I have no choice.’ He shrugged. ‘So there it is.’

‘It’s all right,’ she said, getting up. ‘I understand,’ she added, as if it was him that needed reassurance.

‘Thank you,’ he said.

As he turned away, the woman’s face came into view, a picture of grim satisfaction. Why? Miriam wanted to ask. What possible difference could it make to you?

Another passenger looked up as she left the car, an older woman with neatly-braided grey hair. Was that helplessness in her eyes?

Miriam walked back down the train, grasping the corridor rail for balance. Was this what life in Berlin would be like? She couldn’t believe it – Uncle Benjamin would have moved somewhere else. In Berlin Jews would live with other Jews, have their own world, their own places to drink tea.

Back in her seat, the glances of her fellow-passengers seemed almost sinister. She took a sip from her bottle, conscious that now she would have to ration her consumption. Torsten had known, she thought, or at least guessed. Why hadn’t he warned her? Embarrassment or shame, she wondered. She hoped it was shame.

She resumed her watch at the window. Silesian fields, meandering rivers, village stations that the train ignored. It stopped at a large town – Sagan, according to the station sign. She had never heard of it, nor of Guben an hour later. Frankfurt, which she remembered from a school geography lesson, was the first thing that day to be smaller than expected.

The last hour seemed quicker, as if the train was eager to get home. By the time the first outskirts of Berlin appeared, the sun was sinking towards the horizon, flashing between silhouetted buildings and chimneys, reflecting off sudden stretches of river. Roads and railways ran in all directions.

Her train ran under a bridge as another train thundered over it, and began to lose speed. A wide street lay below her window, lined with elegant houses, full of automobiles. Moments later a soot-stained glass roof loomed to swallow the train, which smoothly slowed to a halt on one of the central platforms. ‘Schlesischer Bahnhof !’ a voice shouted. Silesian Station.

She pulled down her suitcase, queued in the corridor to leave the coach, and finally stepped down onto the platform. The glass roof was higher, grander, than the one at Breslau, and for several moments she just stood there, looking up, marvelling at the sheer size of it all, as passengers brushed by her en route to the exit stairs. She waited while the crowd eased, watching a strange locomotive-less train leave from another platform, and then started down. A large concourse came into view, milling with people, surrounded with all sorts of stalls and shops and offices. She stopped at the bottom, uncertain what to do. Where was Uncle Benjamin?

A man was looking at her, a questioning expression on his face. He was wearing a uniform, but not, she thought, a military one. He seemed too old to be a soldier.

He came towards her, smiling and raising his peaked cap. ‘I’m here to collect you,’ he said.

‘My uncle sent you?’ she asked.

‘That’s right.’

‘Is he all right?’

‘He’s fine. Nothing to worry about. Some urgent business came up, that’s all.’ He reached out a hand for her suitcase. ‘The car’s outside.’

Into the cage

John Russell lifted his glass, reluctantly tipped the last drops of malt down his throat, and placed it ever so gently down on the polished wooden bar. He could have another, he supposed, but only if he woke the barman. Twisting on his stool, he found an almost depopulated ballroom. A threesome at a distant table was all that remained – the blonde torch singer who had been making everyone nostalgic for Dietrich and her two uniformed admirers. She was looking from one to the other as if she was trying to decide between them. Which she probably was.

It was gone three o’clock. His twelve-year-old son Paul had been asleep in their cabin for almost five hours, but Russell still felt too restless for bed. A turn round the deck, he told himself, a phrase which suggested ease of movement, not the obstacle course of couples in thrall to passion which usually presented itself at this hour. Why didn’t they use their cabins, for God’s sake? Because their wives and husbands were sleeping in them?

He was getting obsessive, he thought, as he took the lift up to the boat deck. Four weeks away from his girlfriend Effi and all he could think of was sex. He smiled to himself at the thought. Thirty more hours at sea, five from Hamburg to Berlin.

It was a beautiful night – still warm, the slightest of breezes, a sky overflowing with stars. He started towards the bow, staring out across the darkly rolling sea, wondering when the French and British coastlines would become visible. Soon, he guessed – they were due to make their stop at Southampton before midday.

He stopped and leant his back against the railings, gazing up at the smoke from the twin funnels as it drifted across the Milky Way. He hoped Effi would like her presents, the red dress in particular. He had gifts for Paul’s mother Ilse and her brother Thomas, things that could no longer be found in Hitler’s never-ending Reich, things – as the popular phrase had it – from ‘outside the cage’.

He sighed. Nazi Germany was everything its enemies said it was, and often worse, but he would still be glad to be back. America had been wonderful, and he had finally managed to swap his British passport for an American one, but Berlin was his home. Their home.

He turned to face the sea. Away on the distant horizon a tiny light was flashing at regular intervals. A lighthouse, presumably. An extremity of France. Of Europe.

It really was time for bed. He walked back down the starboard side and slowly descended seven decks’ worth of stairs. As he let himself into their cabin he noticed the folded sheet of paper which had been pushed under the door. He picked it up, backed out into the corridor, and studied it under the nearest light. It was a four-word telegram from Effi’s sister Zarah: ‘Effi arrested by Gestapo’.

Light was edging round the porthole curtain when he finally got to sleep, and two hours later he was woken, accidentally-on-purpose, by his son. ‘It’s England,’ Paul said excitedly, wiping his breath from the glass. The Dorset coast, Russell guessed, or maybe Hampshire. The town they were passing looked large enough for Bournemouth.

Sat in the bathroom, he wondered whether it would be quicker to leave the ship at Southampton. One train to London, another to Dover, a boat to Ostend, more trains across Belgium and Germany. It might save a couple of hours, but seemed just as likely to add a few. And he very much doubted whether the Europa carried copies of the relevant timetables. He would just have to cope with twenty-four hours of inaction.

At breakfast the elderly couple who had shared their table since New York seemed even more cheerful than usual. ‘Another beautiful day,’ Herr Faeder announced, unaware that his upraised fork was dripping egg yolk onto the tablecloth. ‘We’ve been really lucky on this voyage. Last year we were trapped in our cabins for most of the trip,’ he added for about the fourth time. Russell grunted his agreement, and received a reproachful look from Paul.

‘I can’t wait to get home, though,’ Frau Faeder said. ‘I have a feeling this is going to be a beautiful summer.’

‘I hope you’re right,’ Russell said amicably. The Faeders probably came from another planet, but they’d been pleasant enough company.

Once they’d hurried off to claim their favourite deck chairs, he poured himself another coffee and considered what to tell Paul. The truth, he supposed. ‘A telegram came for me last night,’ he began. ‘After you were asleep.’

His son, engrossed in chasing the record for the largest amount of jam ever loaded onto a single piece of toast, looked up in alarm.

‘Effi’s been arrested,’ Russell told him.

Paul’s jaw dropped open. ‘What for?’ he eventually asked.

‘I don’t know. The telegram just said she’d been arrested.’

‘That’s…’ He searched for an adequate word. ‘That’s terrible.’

‘I hope not.’

‘I expect she said something,’ Paul volunteered after a few moments’ thought. ‘That’s not very serious. Not like murder or treason.’

Russell couldn’t help smiling. ‘You’re probably right.’

‘What are you going to do?’

‘I can’t do anything until we get back. And then…I don’t know.’ Kick up a fuss, he thought, but better not to tell Paul that.

‘I’m sorry, Dad.’

‘Me too. Well, there’s nothing we can do now. Let’s get up on deck and watch the world go by.’

As Herr Faeder had said, it was a beautiful day. The Europa, as they discovered on reaching the bow, was in mid-Solent. ‘That’s Lymington,’ Paul said, after consulting his carefully-copied version of the large chart below decks, ‘and that’s Cowes,’ he added, pointing off to the right. Many small boats were in view, a couple of yachts to the south, white sails vivid against the darker island, a flurry of fishing craft to the north, sunlight flashing off their cabin windows. Only the squawking gulls disturbed the peace.

‘I had a wonderful time,’ Paul said suddenly. ‘The whole trip, I mean.’

‘So did I,’ Russell told him. He smiled at his son, but his heart ached. He knew why Paul had chosen this moment to say what he had, and what he might have added had he been a few years older. His son was a German boy in a German family, with an English father and an American grandmother, and he was growing up in a Germany that seemed bound for war with one or both of those countries. For four happy weeks the boy had been able to step outside the competing inheritances which defined his life, but now he was going home, to where they mattered most.

And though Paul would never say so, Effi’s arrest could only make things worse.

They spent most of the day outside, watching the to-ings and fro-ings at Southampton, the warships anchored in The Nore roadstead off Portsmouth, the freighters in the Channel. The setting sun was colouring the white cliffs gold as they passed through the Straits of Dover, the lights brightening on the Belgian coast as darkness finally fell. They went to bed earlier than usual, but despite hardly sleeping the previous night Russell was still wide awake. He lay there in the dark, wondering what had happened, where Effi was. Maybe she’d already been released. Maybe she was en route to the new women’s concentration camp at Ravensbrück. The thought brought him close to panic.

The Europa docked at Hamburg soon after ten the following morning. It seemed an eternity before disembarkation was underway, but the queue at passport control moved quickly enough. Russell was expecting a few questions about his passport – he’d left the Reich four weeks earlier as a UK citizen and was now returning as an American – but the German Consulate in New York had assured him that his resident status would be unaffected.

The officer took one look at Russell’s passport and one at his face before calling over his supervisor, an overweight man with a large boil above one eye. He too examined the passport. ‘You are travelling directly to Berlin?’ he asked.

‘Yes.’

‘The Berlin Gestapo wish to interview you. About a relative who has been arrested, I believe. You know about this?’

‘Yes.’

‘You must report to Hauptsturmführer Ritschel at the Prinz Albrechtstrasse offices. You must go straight there. Understood?’

‘I need to take my son home first.’

The man hesitated, caught in the familiar Nazi dilemma – human decency or personal safety. ‘That would be inadvisable,’ he said, reaching for the best of both worlds.

‘I’m back,’ Russell thought.

There were no questions about his passport, no search through their American purchases at customs. The taxi-ride to the station reminded Russell of his last visit to the city, when he’d been reporting on the launching of the battleship Bismarck, and the wonderful sight of Hitler struggling to contain himself as the ship refused to move.

Arriving at the station, he bought what seemed the most likely newspaper, but could find no reference to Effi’s arrest. He didn’t know, of course, how long ago she had been in custody. There were forty minutes until the next DZug express left for Berlin, so he parked Paul and the bags at a concourse café table and found a public telephone. Without a full address he had to almost beg the operator for Zarah’s number, and the telephone rang about a dozen times before she answered.

‘Zarah, it’s John.’

‘You’re back? Thank God.’

‘I’m in Hamburg. I’ll be in Berlin this afternoon. Is Effi all right?’

‘I don’t know,’ Zarah almost wailed. ‘They won’t let me see her. I’ve tried. Jens has tried.’

That was bad news – Zarah’s husband Jens was a ranking bureaucrat and ardent Nazi, with all the influence that combination implied. ‘What has she been arrested for?’

‘They won’t tell me. Two men from the Gestapo came to the house, told us that she had been arrested, and that I was to let you know by telegram – they even told me what ship you were on. They said not to tell anyone else.’

‘Has there been anything in the newspapers?’ Russell asked, suspicion growing.

‘Nothing. I don’t understand it. Do you?’ she asked, more than a hint of accusation in her voice.

‘No,’ Russell said, though he probably did. ‘I’ll be back in Berlin about four,’ he told her. ‘The Gestapo want to see me the moment I arrive. I’ll call you after I’ve seen them.’

He hung up and rang a more familiar number, that of Paul’s mother and stepfather. Ilse picked up. Russell briefly explained what had happened, and asked if she could meet the train at Lehrter Station. She said she would.

He walked back across the busy concourse, feeling both relieved and depressed. The whole thing was a set-up, aimed at him. Why else keep it quiet? Effi might have said something out of turn and been reported – it was hardly out of character – but when it came down to it the Gestapo were more than capable of simply making something up. Whichever it was, they had their leverage against him. Which was good news and bad news. Good because it almost certainly meant that he could secure Effi’s release, bad because of what they would want in return.

Paul was looking at the newspaper. ‘The Führer revealed that the new Chancery would have another purpose from 1950,’ he read aloud, ‘but declined to say what that would be.’

A lunatic asylum, Russell guessed, but he didn’t think his son would appreciate the joke.

‘Can we go up to the platform?’ Paul asked.

‘Why not.’

The D-Zug was already standing there, a long red bullet of a train. Paul placed a palm on its shiny side, and Russell could almost hear him thinking:

‘This is what Germans can do.’

They finished lunch an hour into the journey, and Russell slept fitfully for most of the rest. Ilse and her husband Matthias were waiting on the Lehrter Station concourse, and both seemed really pleased to see Paul. Russell thanked them for coming.

‘Do you want a lift?’ Matthias asked.

‘No thanks.’ The idea of them all drawing up outside the Gestapo’s Prinz Albrechtstrasse HQ for a family visit seemed almost surreal, not to mention unwise.

‘I hope it’s all right,’ Paul said. ‘Send Effi…tell her I want us to visit the Aquarium again.’

‘Yes, call us,’ Ilse insisted.

‘I will. But don’t tell anyone else about her arrest. The Gestapo don’t want any publicity.’

‘But…’ Ilse began.

‘I know,’ Russell interrupted her. ‘But we can always make a stink later, if we need to.’

Goodbyes said, Russell deposited his suitcases in the station left luggage and hailed a cab. ‘Prinz Albrechtstrasse,’ he said, ‘the Gestapo building.’ The cabbie grimaced in sympathy.

It was usually a ten minute ride, but the evening rush hour was underway and the bridges across the Spree were choked with traffic. The eastern end of the Tiergarten was crowded with walkers enjoying the late afternoon sunshine. ‘The summer before the war,’ Russell murmured to himself. Or maybe not.

The traffic thinned after the Potsdamerplatz traffic lights, and disappeared altogether as they swung into Prinz Albrechtstrasse. The cabbie took Russell’s money, joked that he wouldn’t wait, and drove off towards the Wilhelmstrasse. Staring up at the grey, five-storey megalith, Russell could see his point.

He’d been in worse places, he told himself, and even managed to think of a couple. Pushing his way through the heavy front doors, he found himself surrounded by the usual high columns and curtains. A great slab of a desk stood in front of a flag which could have clothed half of Africa, always assuming the locals liked red, white and black. Behind the desk, looking suitably dwarfed by his surroundings, a man in official Gestapo uniform – not the beloved leather coat – was reading what looked like a technical manual of some sort. He ignored Russell’s presence for several seconds, then gestured him forward with an impatient flick of a finger.

‘My name is John Russell, and I have an appointment with a Hauptsturmführer Ritschel,’ Russell told him.

‘For what time?’

‘I was asked to come here as soon as I reached Berlin.’

‘Ah.’ The receptionist picked up the telephone, dialled a three-figure number, and asked if Hauptsturmführer Ritschel was expecting a John Russell. He was. Another call produced a uniformed Rottenführer to escort Herr Russell upstairs. He followed the shiny boots up, wondering why the Gestapo rarely wore their uniforms out of doors. A need for anonymity, he supposed. And Heydrich probably liked to economize on laundry bills.

The stone corridors were infinitely depressing. So many offices, so many thugs behind desks.

Hauptsturmführer Ritschel looked the part. A shortish man with thinning fair hair, a face full of ruptured blood vessels and eyes the colour of canal water. There were beads of sweat on his brow, despite the wide open window and a shirt open at the collar. His leather coat was hanging on the door. ‘Herr John Russell?’ he said. ‘How would you like to see Fraulein Koenen?’

‘Very much.’

‘You may have five minutes. No physical contact.’ He turned to the Rottenführer. ‘Take him down and bring him back.’

This time they took a lift. The floors were numbered in the usual way, which seemed somewhat incongruous in the circumstances; basement, in particular, seemed a less than adequate description of the cell-lined corridor which awaited them. The silence of the grave was Russell’s first impression, but this was soon superseded. A woman sobbing behind one door, a restless shuffle of feet behind another. A man’s voice intoning ‘shut up, shut up, shut up’ as if he’d forgotten he was still speaking.

Oh my God, Russell thought. What had they done to her?

The Rottenführer stopped outside the penultimate door on the right, pulled back the sliding panel for a brief glimpse inside, and drew back the two massive bolts. The door opened inwards, revealing Effi in the act of getting her to her feet. As she spotted Russell behind the Rottenführer her face lit up, and she almost jumped towards him.

‘No physical contact,’ the Gestapo man said, spreading his arms to keep them apart.

They stood facing each other. She was wearing grey overalls that lapped around her wrists and ankles, making her look more waif-like than ever. Her black hair looked tousled and unusually dull. She tucked one strand behind an ear. ‘I never liked grey,’ she said.

‘How long have you been here?’ Russell asked.

‘Three nights and three days.’

‘Have they hurt you?’

She shook her head. ‘Not my body, anyway. But this is not a nice place.’

‘Have they told you why you’ve been arrested?’

Effi smiled ruefully. ‘Oh yes. That bitch Marianne Schöner informed on me. You know she never forgave me for getting the part in Mother. According to her, I said that Hitler had achieved the impossible – he’d surrounded himself with midgets yet still managed to look small.’

‘But you didn’t say it?’

‘I probably did. It’s not bad, is it? No, don’t answer that – they’ll have you in here too.’

It was his turn to smile. She was scared and she was angry, but there was still fire in her eyes. ‘They’ve only given us five minutes. I’ll get you out of here, I promise.’

‘That would be good.’

‘I love you.’

‘And I you. I had much better plans for your homecoming than this.’

‘They’ll keep. Paul sends his love, wants to go to the Aquarium with you again.’

‘Send him mine. Have you seen Zarah? Does she know I’m in here?’

‘She’s frantic with worry. They wouldn’t let her see you.’

‘Why not, for God’s sake?

‘I think this is aimed at me.’

She gave him a surprised look.

‘There’s nothing in the papers, nothing to stop them simply letting you go if they get something in return.’

She rubbed the side of her face. ‘Why didn’t I think of that? Oh I’m sorry, John. I should learn to keep my mouth shut.’

‘I wouldn’t want that.’

‘What do they want from you?’

‘I don’t know yet. Just some favourable press, perhaps.’ He glanced at the Rottenführer, as if inviting him to join the conversation.

‘That’s five minutes,’ the man said.

She reached out a hand, but before he could respond the Rottenführer was between them, hustling him out of the cell. ‘Try not to worry,’ Russell shouted over his shoulder, conscious of how fatuous it sounded.

Back upstairs, Hauptsturmführer Ritschel looked, if possible, even more pleased with himself. Russell took the proffered seat and implored himself to remain calm.

‘Your passport,’ Ritschel demanded, holding out a peremptory hand.

Russell passed it across. ‘Has Fraulein Koenen been formally charged?’ he asked.

‘Not yet. Soon, perhaps. We are still taking witness statements. Any trial will not be for several weeks.’

‘And until that time?’

‘She will remain here. Space permitting, of course. It may be necessary to move her to Columbiahaus.’

Russell’s heart sank, as it was supposed to.

‘After sentencing it will be Ravensbrück, of course,’ Ritschel added, as if determined to give a thorough account of Effi’s future. ‘And the sentence – unfairly perhaps – is bound to reflect Fraulein Koenen’s celebrity status. A National Socialist court cannot be seen to favour the rich and famous. On the contrary…’

‘Effi is hardly rich.’

‘No? I understand that her father gave her an apartment on her twenty-fifth birthday. Do many Germans receive that sort of financial help? I did not. And neither, as far as I know, did anyone in this building.’

It was a hard point to argue without free access to all Gestapo bank accounts, which Russell was unlikely to be granted. ‘The court may not share your presumption of guilt,’ he said mildly.

‘You know what she said?’

Russell took a deep breath. ‘Yes, I do. But people have always made jokes about their political leaders. A pretty harmless way of expressing disagreement in my opinion.’

‘Perhaps. But against the law, nevertheless.’ He picked up the passport. ‘Let’s talk about you for a moment. Why have you become an American citizen, Herr Russell?’

‘Because I’m afraid that England and Germany will soon be at war, and I do not wish to be separated from my son. Or from Fraulein Koenen.’

‘Do you feel emotionally attached to America?’

‘Not in the slightest,’ Russell said firmly. ‘It’s a wholly vulgar country run by Jewish financiers,’ he added, hoping he was not overdoing it.

Ritschel looked pleasantly surprised. ‘Then why not become a German citizen?’

‘My newspaper employs me as a foreign correspondent – if I ceased to be foreign I would no longer be seen as a neutral observer. And my mother would see it as a betrayal,’ he added, egging the pudding somewhat. It seemed unwise to mention the real reason, that being a foreigner gave him a degree of immunity, and some hope of getting Paul and Effi out of the country should one or both of them ever decide they wanted to leave.

‘I understand that you wish to keep your job, Herr Russell. But just between ourselves, let’s recognize this “neutral observer” nonsense for what it is. The Reich has friends and enemies, and you would be wise – both for your own sake and that of your lady friend – to make it clear which side of that fence you are on.’ His hand shot out with the passport. ‘Hauptsturmführer Hirth of the Sicherheitsdienst wishes to see you at 11am on Wednesday. Room 47, 102 Wilhelmstrasse.’

Russell took the passport and stood up. ‘When can I see Fraulein Koenen again?’

‘That will depend on the outcome of your meeting with Hauptsturmführer Hirth.’

Standing on the pavement outside, Russell could still feel the movement of the Europa inside him. A black-uniformed sentry was eyeing him coldly, but he felt an enormous reluctance to leave, as if his being only a hundred metres away might somehow help to protect her.

He dragged himself away, and started up the wide Wilhelmstrasse. The government buildings on the eastern side – the Finance, Propaganda and Justice ministries – were all bathed in sunlight, the Führer’s digs on the western side cloaked, rather more suitably, in shadow. At the corner of Unter den Linden he almost sleep-walked into the Adlon Hotel, but decided at the last moment that an encounter with his foreign press corps colleagues was more than he could handle on this particular evening. He felt like a real drink, but decided on coffee at Schmidt’s – if ever he needed a clear head it was now.

The café was almost empty, caught in the gap between its workday clientele and the evening crowd. After taking his choice of the window-seats Russell, more out of habit than desire, reached across for the newspaper that someone had left on the adjoining table. Hitler had opened an art exhibition in Munich, accompanied by the Gauleiter of Danzig and Comrade Astakhov, the Soviet chargé d’affaires. This interesting combination had watched a procession of floats, most of which were described in mind-numbing detail. Sudetenland was a silver eagle, Bohemia a pair of lions guarding the gateway to the East, as represented by a couple of Byzantine minarets. The Führer had gone to see The Merry Widow that evening, but ‘Miss Madeleine Verne, the solo dancer’ had failed to show up.

Who could blame her?

Russell tossed the newspaper back. He didn’t feel ready for re-immersion in Nazi Germany’s bizarre pantomime.

At least the coffee was good. The only decent cup he’d had in America was in the Italian pavilion at the World’s Fair.

Zarah, he reminded himself. The telephone in the back corridor was not being used, and he stood beside it for a few seconds before dialling, wondering what he was going to say. Not the truth, anyway. She picked up after the first ring, and sounded as if she’d been crying.

‘I’ve seen her,’ he said. ‘She’s fine. They’ve told me to come back on Wednesday, and they’ll probably release her then.’

‘Why? I don’t understand. If they’re going to release her, why not now?’

‘Bureaucracy, I think. She has to receive a formal warning from some official or other. They didn’t give me any details.’

‘But she will be released on Wednesday?’

‘That’s what I was told,’ he said. There was no point in her spending the next two days in a state of high anxiety. If the Sicherheitsdienst was playing sick games with them, she’d find out soon enough.

‘Thank you, John,’ she said. ‘They won’t let me see her, I suppose.’

‘I don’t think so. They won’t let me see her again until then. I think it’s probably better to just wait.’

‘Yes, I can see that. But she’s all right.’

‘She’s fine. A little frightened, but fine.’

‘Thank you.’

‘I’ll ring you on Wednesday. Effi will ring you.’

‘Thank you.’

He jiggled the cut-off switch and dialled Ilse’s number. ‘Paul’s in the bath,’ his ex-wife told him.

‘I’ve seen Effi and she’s all right. Can you tell him that?’

‘Of course. But…’

‘I think they’re going to let her go on Wednesday.’

‘That’s good. You must be relieved. More than relieved.’

‘You could say that.’

‘Paul seems to have had a wonderful time.’

‘He did, didn’t he? I hope he doesn’t find the transition too difficult. It’s a bit like coming up from the ocean floor – you need to take your time.’

‘Mmm. I’ll watch for signs. What about this weekend? Are you…’

‘He’ll want to catch up with all of you, won’t he? I’d like to see him, but maybe just a couple of hours?’

‘That sounds good, but I’ll ask him.’

‘Thanks, Ilse.’

‘I hope it all goes well.’

‘Me too.’

He went back to the rest of his coffee, ordered a schnapps to go with it. He supposed he should eat, but didn’t feel hungry. What would Heydrich’s organization want from him? More to the point, would it be something in his power to give? The Sicherheitsdienst – the SD, as it was popularly known – had started life as the Nazi Party’s intelligence apparatus, and now served the Nazi state in the same role. It thrived on betrayals, but the only person Russell could betray was himself. No, that wasn’t strictly true. There was the sailor in Kiel who had given him the Baltic fleet dispositions, not to mention the man’s prostitute girlfriend. But if the SD knew anything about Kiel, he wouldn’t be drinking schnapps in a café on the Unter den Linden.

So what did they want him for? As an informant, perhaps. A snitch in the expatriate community. And among the German press corps. He had a lot of friends and acquaintances who still wrote – with well-concealed disgust in most cases – for the Nazi press. Effi might be asked to report on her fellow thespians.

Or maybe they were more interested in his communist contacts. They certainly knew about his communist past, and after the business in March they probably had a highly exaggerated notion of his current involvement. They might want to use him as bait, luring comrades up to the surface.

The latter seemed more likely on reflection, but who knew what the bastards were thinking?

He paid the bill and stood out on the pavement once more. Where to go – his rooms in Hallesches Tor or Effi’s flat, where he’d been spending the majority of his nights? Her flat, he decided. Check that everything was all right, make sure the Gestapo had remembered to flush.

When it came down to it, he just wanted to feel close to her.

He walked through to Friedrichstrasse and took a westbound Stadtbahn train. There was a leaflet on the only empty seat. He picked it up, sat down, and looked at it. ‘Do you want another war?’ the headline asked him. The text below advised resistance.

Looking up, he noticed that several of his fellow-passengers were staring at him. Wondering, he supposed, what he was going to do with the treasonous missive now that he’d read it. He thought about crumpling the leaflet up and dropping it, but felt a sudden, unreasoning loyalty to whoever had taken the enormous risk of writing, producing and distributing it. A minute or so later, as his train drew into Lehrter Station, he placed the leaflet back on the seat where he’d found it and got off. The attractive young woman sitting opposite gave him what might have been an encouraging smile.

He collected his suitcases from the left luggage, took another train on to Zoo Station, and walked the half-kilometre to Effi’s flat on Carmerstrasse. Everything looked much as he’d last seen it – if the Gestapo had conducted a search then they’d tidied up after themselves. So they hadn’t conducted a search. Russell sniffed the air for a trace of Effi’s perfume but all he could smell was her absence. He leaned against the jamb of the bedroom door, picturing her in the cell. He told himself that they wouldn’t hurt her, that they knew the threat was enough, but a sliver of panic still tightened his chest.

He stood there, eyes closed, for a minute or more, and then urged himself back into motion. His car should be here, he realized. He locked up and carried his cases back down. The Hanomag was sitting in the rear courtyard, looking none the worse for a month of Effi’s erratic driving. It started first time.

Twenty minutes later he was easing it into his own courtyard on Neuenburgerstrasse. He felt less than ready to face Frau Heidegger and the inevitable deluge of welcome home questions, but the only way to his room led past her ever-open door. Which, much to his surprise, was closed. He stood there staring at it, and suddenly realized. The third week of July – the annual holiday with her brother’s family in Stettin. Her sour-faced sister would be filling in, and she had never shown the slightest interest in what was happening elsewhere in the building. Frau Heidegger was fond of claiming that the life of a portierfrau was a true vocation, but her sister, it seemed, had not heard the call.

He lugged the suitcases up to his fourth floor rooms, and dumped them on his bed unopened. The air seemed hot and stale, but throwing the windows wide made little difference – night was falling much faster than the temperature, and the breeze had vanished. There were two bottles of beer in the cupboard above the sink, and Russell took one to his favourite seat by the window. The beer was warm and flat, which seemed appropriate.

None of it was going to go away, he thought. Effi might be released on Wednesday, but they could always re-arrest her, and next time they might feel the need – or merely the desire – to inflict a little pain. If Effi left him – God forbid – there was always Paul. Some sort of pressure could always be applied. The only way to stop it was to leave, and that would mean leaving alone. They would never let Effi out of the country now, and Ilse would never agree to Paul going. Why should she? She loved the boy as much as he did.

If he left, they’d all be safe. The bastards would have nothing to gain. Or would they? They’d probably find jobs for him to do in Britain or the US. Do you care what happens to your family in Germany? Then do this for us.

He needed to talk to someone, he realized. And there was only Thomas, his former brother-in-law, his best friend. The only man in Berlin – on Earth, come to that – whom he would trust with his life.

He went back downstairs to the telephone.

Thomas sounded happy to hear from him. ‘How was America?’ he asked.

‘Wonderful. But I’ve run into a few problems since I got back.’

‘How long have you been back?’

‘In Berlin, about six hours. I’d like a chat, Thomas. Can you find me a half hour or so tomorrow morning if I come to the works?’

‘I imagine so. But wouldn’t you rather have lunch?’

‘I need a private chat.’

‘Ah. All right. Ten-thirty? Eleven?’

‘Ten-thirty. I’ll be there.’ Hanging up, he realized he hadn’t even asked after Thomas’s wife and children.

Back in his room he sat in the window, taking desultory swigs from the second bottle of beer. The roofs of the government district were visible in the distance, a barely discernible line against the night sky. He thought of Effi in her cell, hoped she was curled up in sleep, cocooned from the evil around her.

The Schade Printing Works were in Treptow, a couple of streets from the River Spree. As Russell parked the Hanomag alongside Thomas’s Adler, a ship’s horn sounded on the river, a long mournful sound for such a bright morning. Russell had only managed a few dream-wracked hours of unconsciousness, and the coffee he’d grabbed at Görlitzer Station had propelled his heart into an unwelcome gallop for longer than seemed safe.

The main print room was the usual cacophony of machines. Thomas’s office was at the other end, and Russell exchanged nods of recognition with a couple of the men on his way through. Both looked like Jews, and probably were. Schade Printing Works employed a higher percentage of Jews than any business in Berlin, largely because Thomas insisted that he needed all his highly-skilled workforce to fulfil his many contracts with the government. The irony was not lost on his Jewish workers, much of whose work involved printing anti-Semitic tracts.

A smiling Thomas arose from his desk to shake Russell’s hand. ‘God, you look terrible,’ he half-shouted over the din. ‘What’s happened?’ he added, seeing the look in his friend’s eyes.