26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

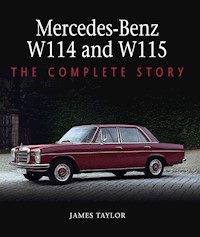

The W114 and W115 models were enormously successful for Mercedes-Benz, and their sales in nine years of production between 1967 and 1976 almost equalled the total of all Mercedes passenger models built in the 23 years between 1945 and the time of their introduction in 1968. There were many reasons for this success, but perhaps the most important was that Mercedes expanded the range to include a simply vast amount of variants including four-cylinder and six-cylinder petrol engines, four-cylinder diesels; saloons, coupes and long-wheelbase models. With around 200 photographs, this book features the story of the design and development of the W114 and W115 ranges. It gives full technical specifications, including paint and interior trim choices; includes a chapter on the special US variants; gives production tables and model type codes and explores the Experimental Safety Vehicles developed from these cars. Finally, there is a chapter on buying and owning a 114- or 115-series Mercedes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 262

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Mercedes-BenzW114 and W115

THE COMPLETE STORY

OTHER TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV and Spider

Aston Martin DB4, DB5 & DB6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Austin Healey 100 & 3000 Series

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupés 1965-1989

BMW Z3 and Z4

Citroen DS Series

Classic Jaguar XK: The 6-Cylinder Cars 1948–1970

Classic Mini Specials and Moke

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Ford Consul, Zephyr and Zodiac

Ford Transit: Fifty Years

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta Road and Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar F-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 and 2, S-Type and 420

Jaguar XJ-S

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Jowett Javelin and Jupiter

Lamborghini Countach

Land Rover Defender

Land Rover Discovery: 25 Years of the Family 4Å~4

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

MG T-Series

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Cars of the 1990s

Mercedes-Benz ‘Fintail’ Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class

Mercedes-Benz W113

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126

Mercedes-Benz W201

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes SL & SLC 107 1971–2013

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos 1974–1996

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera: The Air-Cooled Era

Porsche Carrera: The Water-Cooled Era

Porsche Water-Cooled Turbos 1979–2019

Range Rover: The First Generation

Range Rover: The Second Generation

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley: The Legendary RMs

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover P6

Rover SD1

Saab 99 & 900

Shelby and AC Cobra

Subaru Impreza WRX and WRX STI

Sunbeam Alpine & Tiger

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire & GT6

Triumph TR6

Triumph TR7

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

Mercedes-BenzW114 and W115

THE COMPLETE STORY

JAMES TAYLOR

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

enquiries@crowood.com

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© James Taylor 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 825 2

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The W114 and W115 models were very important to Mercedes, as the first model range of which the company built more than a million examples. They earned huge respect around the world and were in many ways the first really modern Mercedes, ushering in an age of solid, dependable saloons that continued with the W123 and W124 models for nearly another three decades. They made stylish coupés more affordable than ever before and they fulfilled extremely valuable roles as taxis and as the basis of ambulances and other essential vehicles. Not for nothing were they a common sight in police livery in their native West Germany.

These were the Mercedes saloons that earned my personal respect when I was younger. I still remember vividly conversing with the French taxi driver who collected me in one sometime around 1975 and proudly informed me that the car we were in had covered over 200,000km (124,275 miles) and was in his opinion likely to be good for the same again. It was his second example of the breed. Stylish it was not – but if it was that reliable, I could see why he thought so highly of it.

In preparing this book, I am pleased to acknowledge the help of Mercedes-Benz Classic and the Daimler-Benz Media site, both for information and for the majority of the illustrations. Thanks, too, go to the press office of Mercedes-Benz UK, which provided a great deal of information and many pictures of when the cars were new. Over the years, I have picked up a lot of information from members of the Mercedes-Benz Club in the UK and from its excellent publication, the Gazette, and I have made full use of the material available in German about the W114s and W115s.

Special thanks go to the many photographers who have made their work available for use through WikiMedia Commons, and to Magic Car Pics, who supplied a number of excellent pictures. Lastly, I am very grateful to Pierre Hedary of the Mercedes-Benz Club USA, who kindly agreed to check my chapter on the US models for errors and ended up checking most of the book. Whatever mistakes it still contains can only be my responsibility and I would be very pleased to hear about them through the publisher.

James TaylorOxfordshireMay 2020

TIMELINE

1961

Initial consideration of a new medium-sized Mercedes range

1964

First prototypes on the road

1966

Styling signed off

1967, December & 1968, January

Press launch

1968, March

Public launch at Geneva Show; six modelsFirst long-wheelbase models built

1968, September

Introduction to USA

1968, October

Coupé introduced as 250C and 250CE with injected petrol engine

1970, July

2.8-litre engine for 250 models in some markets

1971–1972

Experimental Safety Vehicles based on W114 saloons

1972, May

280 models replace 250 types

1973, October

Facelifted (Series 2) range introduced

1974, July

Introduction of 5-cylinder diesel engine (240D 3.0 in Europe, 300D in USA)

1976, December

Last W114 and W115 models built

CHAPTER ONE

SETTING THE SCENE

By the time Mercedes released its fourth generation of post-war medium saloons in 1968, the company had become one of the leaders of the global motoring scene. Hugely respected in Europe during the interwar years, it had taken a more global view after the end of World War II and had gradually built up a worldwide sales and service network that other manufacturers could only envy.

Yet the reputation that Mercedes cars enjoyed in the 1960s had not been easy to attain. It had been achieved through top-quality engineering and through steady expansion into countries around the world, for by the end of World War II, Mercedes-Benz and its parent company, Daimler-Benz, had been broken almost beyond repair. As a leading German engineering company, Daimler-Benz had inevitably been drawn into providing war materiel for Hitler’s Third Reich and, equally inevitably, its factories had been a key target for the Allies who were determined to prevent Hitler’s brand of fascism from spreading beyond Germany. The Daimler-Benz Board in 1945 famously and sadly admitted that the company had, by that stage, ‘practically ceased to exist’.

With its bombed factories in ruins and some irretrievably lost to the Russian Occupation Zone in the east, the company could only make a cautious start. Besides, the whole of what was now West Germany was subject to management by the Allied Control Commission, which was tasked with promoting economic and social recovery, but also with ensuring that German industrial output should not be allowed to exceed roughly half of its 1938 level. The Daimler-Benz factories that were still able to function were initially permitted to undertake repair and maintenance work on existing vehicles; only later did actual assembly of new ones begin. The exception was the Mannheim truck plant, which had remained relatively undamaged and here production of 3-ton trucks resumed during 1945. Such vehicles were more necessary to rebuild the economy than cars.

Miraculously, however, the production lines for the pre-war 170V saloon had survived the bombing. There was no call yet for saloon cars, but it was not difficult to adapt the chassis, engine and front panels of the 170V as the basis of a light commercial vehicle. So that was what began in November 1945 to roll from the assembly lines at the Untertürkheim and Sindelfingen factories in Stuttgart that had been primary targets of Allied bombing. Production was slow to build up. In 1946, just 214 vehicles were built; in 1947 the total was 1,045, but by 1948 recovery was more obviously under way and 1,304 were built in just under six months up to 20 June that year. They took several different forms, to meet demand – there were delivery vans, pick-ups, personnel carriers (for the new West German police) and ambulances.

Mercedes started car production in 1946 with vans and pick-ups based on this pre-war saloon model. The car pictured is a 170Va, which was still in production up to 1952.

Demand was for vehicles to help the recovery of the West German economy and Mercedes shrewdly bought the rights to a design for a multi-purpose agricultural type that used one of its engines. It was called the Unimog and its descendants are still in production more than seventy years later.

As the post-war difficulties began to ease, the Allies granted approval for Daimler-Benz to begin car manufacture again. There had been neither time nor finance to develop anything new, so the first saloons to emerge in May 1947 were almost carbon copies of the pre-war models. But conditions in West Germany continued to improve and at the Hanover Fair in May 1949 Daimler-Benz was able to unveil not only its first all-new post-war truck (the L3500), but also two new saloon cars. Based on the 170V, these expanded the range by adding a diesel engine (in the 170D) and a more roomy and substantial body with a more powerful engine (in the 170S). Cabriolet and coupé body options were added for the 170S, then in 1951 came a new 6-cylinder engine that created the 220 models in essentially the same structure. That same year, Mercedes-Benz introduced its first post-war luxury model – the big 6-cylinder 300 limousine that would become synonymous with West German officialdom during the 1950s.

The L3500 truck was Mercedes’ first new post-war design and made a major contribution to the company’s recovery. The one pictured is a preserved 1952 example used as a brewer’s dray.

These cars established a shape for the Mercedes range that would endure for a further decade and a half. There would be a medium-sized saloon and a big luxury saloon, and from 1954 the range was expanded to include sports cars as well, which of course depended on running gear initially developed for the saloon models. The old 170s and 220s gave way in 1953 to the second post-war generation of saloons, with modern unitary construction bringing them the nickname of ‘Ponton’ models (the word is German for pontoon, with the construction being reminiscent of a pontoon bridge). They had a range of engines that began with 1.8-litre 4-cylinder petrols and diesels and ran all the way up to 2.2-litre 6-cylinder petrol types. The 6-cylinder cars needed a ‘long-nose’ body shell, but had fundamentally the same design as the 4-cylinder types and in 1958 embraced ultra-modern fuel injection (earlier seen in the 300SL sports models) with the 220SE model.

Mercedes got back to building big luxury models for business leaders as soon as it could. This is the 300 model (internally coded W186) of 1951. There would be coupé and cabriolet derivatives later.

The monocoque Ponton models replaced the old pre-war designs from 1953 as the mainstream saloons. This is a late model, built in 1959 for a British buyer and close to the top of the range when new. It is a 220S model with a 6-cylinder engine.

Several factors had made this huge expansion of the Mercedes car range possible. One, of course, was the booming West German economy (the Wirtschaftswunder, or ‘economic miracle’) that had brought prosperity back to the country in the decade after the war. The other was a determined focus on export sales. Although the Daimler-Benz success in this area had largely been dependent on its truck and bus sales, with car sales following, in the USA the cars had made their own success story. Thanks to the entrepreneurial spirit of American importers, notably Max Hoffman on the east coast, Mercedes came to the attention of the rich and famous in North America. The 300SL and 190SL sports models of 1953 and 1954 were created largely for them and it was these and the glamorous coupés and cabriolets that established a lasting image for the Mercedes marque in the USA.

Sports cars followed Mercedes’ determination to get back into motorsport. This is the legendary W198 300SL ‘Gullwing’, so-called because of its upward-opening doors.

The importance that Mercedes attached to the American market became very obvious when the company introduced its third generation of medium-sized saloons in 1959. These were distinguished by discreet but unmistakable tail fins in the American idiom of the period; in the design stages, they had been larger than they became in production, being toned down for fear of upsetting European buyers who were less enthusiastic about the American fashion for fins and chrome. These cars, known to English speakers as ‘Fintail’ models (the Germans call them Heckflossen), directly replaced the Pontons with a similar range of engines. However, from 1961 they were also made available with the 3-litre 6-cylinder engine from the bigger luxury saloons – and that would have further consequences later on.

By the early 1960s, Mercedes had identified that there was a growing demand for luxury family saloons that were more expensive than its existing 6-cylinder models, but nonetheless not as grand or formal as its large 300 limousines. So in 1965, a new model was introduced to meet that demand. Cautiously based on the Fintail platform and running gear, this was available only with 6-cylinder engines of 2.5-litres and above, with a more spacious and substantial-looking body that developed the more rounded look introduced for the coupé and convertible derivatives of the Fintails. It was known as the S Class – the S supposedly standing for Super – and its arrival placed a new and very clear limit on the upper end of the medium-sized saloon range.

The 300SL was an exotic supercar, but in 1954 there followed an affordable sports roadster. The 190SL drew its 4-cylinder engine from the Ponton saloon range.

So it was that when work began at Stuttgart in the mid-1960s on a new medium-sized range, it was constrained by the need to offer less prestige than the S-Class models and by the need to offer engines that were no larger than the 2.5-litre size available in the entry-level S Class. But it was also free to develop in its own way without the constraint that the same basic design had to cater for a very different area of the market in addition to its core customers. That, at least, was the starting point. The position would change as time went by.

Mercedes was well attuned to the likes of US buyers by the mid-1950s and in 1957 introduced this roadster version of the 300SL to meet them.

The Fintail models replaced the Pontons as the mainstream saloon range from 1959 and the more expensive variants took the design of their vertically stacked headlight units from the 300SL roadster. This one is a 1966 230S with a 6-cylinder engine that was sold in Britain.

Top models of the Fintail range had a new 3-litre 6-cylinder engine with fuel injection, as in this 1962 300SE. The rear view shows where the Fintail name comes from and displays the extra chrome fitted to these expensive variants.

MERCEDES-BENZ DIESEL ENGINES

Mercedes-Benz was a pioneer in the field of diesel engines for passenger cars, having introduced its first such model – the 260D with a 2.6-litre engine – in 1936.

The company persisted with its diesel technology, adding a diesel-engined 170D to the range in 1949, then making a 180D model available when the new Ponton saloons were introduced in 1952. Diesel Fintails followed in 1961 and by 1968 the company had sold 360,000 of them. Few other companies were taking diesel passenger cars very seriously at the time. Mercedes diesel car engines were never very powerful, with Mercedes petrol engines of the same capacity always having much higher outputs. However, they were frugal, reliable and durable, and these characteristics made them favourites with taxi drivers all over the world where the diesel Mercedes was sold. By 1968, if there had been no diesel variant of the W115 saloons, Mercedes’ global passenger car sales would have been very substantially affected.

MERCEDES FACTORIES

Mercedes-Benz passenger cars were made by a division of the Daimler-Benz company, which had been established in 1926 when the two leading car companies in Germany merged for mutual benefit. The company had always had its headquarters at Stuttgart in southern Germany, but over the years had also opened several factories in other parts of Germany, as well as overseas.

The design headquarters, the body plant and the main car assembly lines were located in Sindelfingen, a small city some 15km (9 miles) from Stuttgart. Production of engines, transmissions and axles was the responsibility of a second factory at Untertürkheim, in the outer suburbs of Stuttgart, although this was supported by some other smaller plants in the same region. Also at Untertürkheim was the research and development division, which had its own banked test track.

Daimler-Benz also had several other factories in West Germany, which were devoted to the production of trucks and buses.

Mercedes in Britain

Mercedes-Benz models were rare in early post-war Britain, although small numbers – generally of the more glamorous types – had been imported during the interwar years. After 1945, foreign car imports were only a trickle until the 1954 relaxation of import restrictions that had been designed to protect the domestic car industry and Mercedes-Benz did not attempt to gain a foothold before that date. Early imports focused on the more expensive types; at the 1955 London Motor Show, for example, there were examples of the 6-cylinder 220 saloon and convertible, the 300SL and 190SL sports models and the 300 limousine. Mercedes-Benz (GB) Ltd did quote a price for the 180 Ponton saloon, but at £1,694 0s 10d inclusive of taxes it was more expensive than some domestic models with engines of 3-litre or larger capacities and simply stood no realistic chance of success.

One result of this focus on the more expensive models was that Mercedes became associated with glamorous and expensive cars in Britain during the 1950s. Few Britons were aware that there were any ‘cheaper’ Mercedes, let alone the fact that vast quantities of them were exported to undeveloped countries around the world where they were much prized as rugged, reliable and long-lived taxis. Mercedes-Benz (GB) traded on its luxury image, of course, and in Britain there was always a distinct hint of superiority and exclusivity attached to the Fintail models, whatever their engine size.

By the time the fourth-generation medium saloons that are the focus of this book came on to the scene, there was therefore a very clear expectation in Britain that they would be solidly built in the Mercedes tradition, supremely reliable and superior in many respects to the domestic product. What changed, albeit gradually, was the notion of exclusivity. As the new cars reached Britain in greater numbers, that was gradually eroded – although Mercedes-Benz (GB) did a magnificent job of maintaining the illusion that Mercedes cars were as exclusive as they had ever been. Even now, half a century later, the illusion still lingers.

Mercedes in the USA

The importers’ determined focus in the early 1950s on the glamorous end of the Mercedes range helped to build a similar image of exclusivity in the USA. American commentators were almost invariably impressed by the attention to detail and the superb build quality of Mercedes models, which they contrasted with the distinctly shoddy products that sometimes came from their own domestic manufacturers. This contrast also contributed to the image of Mercedes-Benz superiority and of course the company sat back and enjoyed the sales that followed.

In the beginning, sales were not enormous. By early 1957, only 6,432 Mercedes cars had been sold in the USA since an agreement had been signed with importer Max Hoffman in 1952. Keen to play for higher stakes, Daimler-Benz terminated the contract with Hoffman and signed a new one with the Studebaker-Packard Corporation. However, that company ran into trouble early in the new decade and in 1964 was obliged to close down its US factory (although some production continued in Canada). So in 1965 Daimler-Benz set up two new wholly-owned subsidiaries to handle sales and service in North America. Mercedes-Benz of North America Inc. was based in Fort Lee, New Jersey, and Mercedes-Benz of Canada Ltd in Toronto. Over the next few years, these subsidiaries oversaw a major expansion of car sales.

Despite the glamour, Mercedes also had a rather conservative image in the USA. This had arisen partly because the company did not make highly obvious annual model changes in the American fashion, but also because it tended to rely on tried and tested engineering that had been in production for several years. So expectations in the USA were quite high when the W114 and W115 saloons were introduced in 1968.

Safety Engineering

From the start of the 1960s, Mercedes also developed a formidable reputation for engineering safety into its cars. The focus on safety began several years before Ralph Nader’s 1965 book, Unsafe at Any Speed, prompted the US car industry to take safety seriously and the first crash test in the history of the brand took place on 10 September 1959. The car used for the test was an example of the soon to be introduced Fintail saloons and it was rammed head-on into a solid wall in order that the engineers could see exactly how the structure behaved on impact and how the (dummy) driver was thrown about in the crash.

Safety had been central to the conception of the Fintail saloons. In business terms, Mercedes expected it to represent a feature that other manufacturers did not have and one that would give them an edge in the marketplace. They could not, of course, have envisaged how Federal legislation would turn safety into a requirement just a few years later.

Central to the safety engineering for the Fintail models was the concept of the ‘crumple zone’, in which controlled deformation of the front and rear elements of the car absorbs the energy of an impact while the passengers are protected from it in a rigid central section of the body. The concept was developed by an Austro-Hungarian inventor, Béla Barényi, as early as 1937. He joined Mercedes-Benz in 1939, but it was not until 1952 that his ideas were patented and partially implemented in the body structure of the Ponton saloons. Full implementation, however, came in 1959 with the Fintail models.

The Fintail range was developed to include two-door coupé and cabriolet models, which had entirely different bodywork from the saloons. This is an early coupé, showing the hardtop style that would become a Mercedes staple in the years that followed.

The SL roadster for the 1960s was the Pagoda model, seen here with its hardtop in place as an early 230SL model.

It became clear that there would be buyers for a separate range of saloons, priced higher than the Fintails. They were developed from the Fintail platform, but were visually more akin to the big coupés. This is a W109 300SEL, the top model with extended wheelbase and air suspension.

Nevertheless, there was more to the Mercedes concept of safety engineering than that. Protecting the occupants in a collision was described as ‘passive’ safety. A second element in making the car safer was ‘active’ safety, which depended upon the optimization of controls and the driver’s environment to prevent accidents from happening in the first place. All this received widespread publicity and was taken as read by the middle of the decade, when other companies were obliged to play catch-up according to Federal legislation. By the time of the W114 and W115 models, however, Mercedes was able to claim a moral advantage over its competitors, with the company having many more years of experience in engineering for safety.

Rational Engineering, Rational Marketing

Very much characteristic of Mercedes cars by the mid-1960s was a sense of logic about them. Design solutions typically appeared to have been thought through carefully before being implemented on production – as indeed they had been. Some people find that this approach creates relatively characterless cars; others that it actually creates the very distinctive character of a Mercedes-Benz. One way or another, that same approach continued to be apparent right through into the 1990s, at which point marketing appeal began to take an increasingly important role in design.

Marketing nevertheless had an important role in the 1960s as well, but it was rather different. What the marketing people at Mercedes did was to decide on a core or minimum specification for each range of the company’s cars, then add features from the list of those drawn up by the designers to give each model a level of equipment appropriate to its price. This led to some models having a very low level of standard equipment, sometimes with a long list of very expensive options. Mercedes was at times accused of making everything worth having into an extra-cost option and it is hard to argue with that perception. It also meant that some options remained very rare indeed. That same approach would colour the showroom specifications of the W114 and W115 models throughout their production life.

Overseas Assembly

Lastly, Mercedes had set up not only an impressive overseas sales and service network for its products, but in some countries it had established assembly plants. Typically, these were used to get around prohibitive import tariffs in some countries; a local assembly operation was nevertheless permitted because it offered work for the local labour force and provided training in skills that had not previously existed in the country.

These assembly plants were fed with what were in effect kits of parts – Completely Knocked Down or CKD – that had been manufactured in Germany. The degree of preassembly depended on the skills available in the country of assembly, so the kits were not always the same from one country to the next. In some cases, locally manufactured components were added into the mix – items such as glass, tyres, batteries, or paint – thus providing a further boost to the economy of the host country. In a very few countries, local skills were of an order that allowed that country’s engineers to tailor the basic German product for a specific customer requirement. By the time of the W114 and W115 models, overseas assembly from CKD had attained a very sophisticated level, as Appendix I reveals.

By the late 1960s, the Mercedes passenger-car range looked like this. The mainstream saloons were the W114 and W115 saloons that are the focus of this book. Above them came the W108 and W109 S-Class cars and the big W111 coupés and cabriolets. Right at the top of the range and intended for heads of state and the very wealthy were the W100 600 models; seen here are a white saloon and a black long-wheelbase limousine derivative.

MERCEDES-BENZ MODEL AND ENGINE CODES

Mercedes had a well-established system of project codes by the time it started work on the W114 and W115 saloons. New car projects were allocated a code beginning with W, which stood for Wagen (German for ‘car’). This was followed by a three-digit number, apparently chosen largely at random. Nevertheless, runs of numbers were sometimes used and the W114 and W115 codes were part of an unusually long sequential run, although the cars were by no means developed or introduced in numerical order. Note that the initial code was varied for the 107 range, R standing for Roadster:

R107SL roadster (1971)W108S Class (1965)W109S Class with long wheelbase and air suspension (1966)W1104-cylinder (short-nose) Fintail (1961)W1116-cylinder (long-nose) Fintail (1959)W1126-cylinder Fintail with air suspension (1962)W113Pagoda SL sports model (1963)W1146-cylinder New Generation (1968)W1154-cylinder New Generation (1968)W116second-generation S Class (1972).Engine codes always began with M (for Motor, always petrol-powered), or OM (Ölmotor, or diesel engine). These also typically had a three-digit identifying number. So among the engines used in the W114 and W115 models were the M180 and the OM615 types.

CHAPTER TWO

DESIGN

It is more or less standard practice in the motor industry to begin thinking about the eventual replacement for a new model as soon as that model reaches the showrooms. That, according to official versions of Mercedes-Benz history, was exactly what happened with the cars that would be introduced in 1968 to replace the Fintail saloons. The Fintails were introduced in two stages, with 6-cylinder models arriving in 1959 and 4-cylinder variants following in 1961, and it was in 1960 that Fritz Nallinger at Mercedes prepared his first ideas for the range that was to replace them.

Nallinger was a long-time Mercedes employee. He had joined the company in 1922, four years before Daimler and Benz had merged to create Daimler-Benz and the Mercedes-Benz passenger car marque, and had gradually risen through the ranks. He became a member of the Executive Board in 1941 and, now in his early sixties, was the company’s Technical Director, its chief engineer with responsibility for the development of new products. His thoughts on the company’s new mainstream saloon range were coloured by his experience in overseeing Fintail development and by changes in the demand for Mercedes-Benz saloons.

Fritz Nallinger was the Technical Director. This picture shows him as a younger man, in 1940.

On the one hand, Nallinger could see very clearly that it was wasteful of resources to develop one version of a design to suit 4-cylinder engines and another to suit 6-cylinder engines. This was the way the Fintails had been developed, but Nallinger determined that their replacements would have a single basic design that would suit both 4-cylinder and 6-cylinder engines with a minimum of differences between them.

He also realized that the ‘luxury’ version of the Fintails, which would reach the showrooms in 1962 and featured air suspension, represented only the start of a new development. He therefore developed a far-sighted new strategy that would see these models replaced by a separate luxury range, priced above the mainstream saloons. It would be this part of the strategy that would be implemented first, as the W108 S-Class saloons were developed in the early 1960s to be launched in 1965.

The finished product, as seen in a sketch from the styling studio. The signature is that of Paul Bracq, who led the styling teams on the W114 and W115 project.

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: