1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Diamond Book Publishing

- Sprache: Englisch

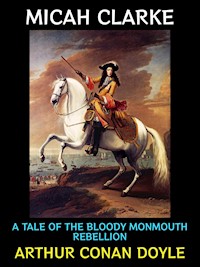

Narrated by the character for whom the title is named and set in the late 1600's, Micah Clarke describes the battle of peasants against the existing king of England in the hopes that they can replace the monarch with his brother who feels he has been unjustly denied the throne. Micah Clarke, a young, innocent peasant joins forces with other peasants, among the Puritans, to fight for this pathetic duke's cause. It was attempt by Conan Doyle to present the story of the Puritans in a more favorable light than generally thought of in England at the time the book was written – a historical romance about the Monmouth rebellion and 'Hanging Judge' Jeffries told by a humble adherent of the Duke of Monmouth – the whole story of the rising in Somerset, the triumphant advance towards Bristol and Bath, and the tragic rout at Sedgemoor (1685).

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Arthur Conan Doyle

Micah Clarke Preview

A Tale of the Bloody Monmouth Rebellion

Table of contents

CHAPTER I. OF CORNET JOSEPH CLARKE OF THE IRONSIDES

By

Arthur Conan Doyle

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I. OF CORNET JOSEPH CLARKE OF THE IRONSIDES

CHAPTER II. OF MY GOING TO SCHOOL AND OF MY COMING THENCE

CHAPTER III. OF TWO FRIENDS OF MY YOUTH

CHAPTER IV. OF THE STRANGE FISH THAT WE CAUGHT AT SPITHEAD

CHAPTER V. OF THE MAN WITH THE DROOPING LIDS

CHAPTER VI. OF THE LETTER THAT CAME FROM THE LOWLANDS

CHAPTER VII. OF THE HORSEMAN WHO RODE FROM THE WEST

CHAPTER VIII. OF OUR START FOR THE WARS

CHAPTER IX. OF A PASSAGE OF ARMS AT THE BLUE BOAR

CHAPTER X. OF OUR PERILOUS ADVENTURE ON THE PLAIN

CHAPTER XI. OF THE LONELY MAN AND THE GOLD CHEST

CHAPTER XII. OF CERTAIN PASSAGES UPON THE MOOR

CHAPTER XIII. OF SIR GERVAS JEROME, KNIGHT BANNERET OF THE COUNTY OF SURREY

CHAPTER XIV. OF THE STIFF-LEGGED PARSON AND HIS FLOCK

CHAPTER XV. OF OUR BRUSH WITH THE KING’S DRAGOONS

CHAPTER XVI. OF OUR COMING TO TAUNTON

CHAPTER XVII. OF THE GATHERING IN THE MARKET-SQUARE

CHAPTER XVIII. OF MASTER STEPHEN TIMEWELL, MAYOR OF TAUNTON

CHAPTER XIX. OF A BRAWL IN THE NIGHT

CHAPTER XX. OF THE MUSTER OF THE MEN OF THE WEST

CHAPTER XXI. OF MY HAND-GRIPS WITH THE BRANDENBURGER

CHAPTER XXII. OF THE NEWS FROM HAVANT

CHAPTER XXIII. OF THE SNARE ON THE WESTON ROAD

CHAPTER XXIV. OF THE WELCOME THAT MET ME AT BADMINTON

CHAPTER XXV. OF STRANGE DOINGS IN THE BOTELER DUNGEON

CHAPTER XXVI. OF THE STRIFE IN THE COUNCIL

CHAPTER XXVII. OF THE AFFAIR NEAR KEYNSHAM BRIDGE

CHAPTER XXVIII. OF THE FIGHT IN WELLS CATHEDRAL

CHAPTER XXIX. OF THE GREAT CRY FROM THE LONELY HOUSE

CHAPTER XXX. OF THE SWORDSMAN WITH THE BROWN JACKET

CHAPTER XXXI. OF THE MAID OF THE MARSH AND THE BUBBLE WHICH ROSE FROM THE BOG

CHAPTER XXXII. OF THE ONFALL AT SEDGEMOOR

CHAPTER XXXIII. OF MY PERILOUS ADVENTURE AT THE MILL

CHAPTER XXXIV. OF THE COMING OF SOLOMON SPRENT

CHAPTER XXXV. OF THE DEVIL IN WIG AND GOWN

CHAPTER XXXVI. OF THE END OF IT ALL

CHAPTER I. OF CORNET JOSEPH CLARKE OF THE IRONSIDES

It may be, my dear grandchildren, that at one time or another I have told you nearly all the incidents which have occurred during my adventurous life. To your father and to your mother, at least, I know that none of them are unfamiliar. Yet when I consider that time wears on, and that a grey head is apt to contain a failing memory, I am prompted to use these long winter evenings in putting it all before you from the beginning, that you may have it as one clear story in your minds, and pass it on as such to those who come after you. For now that the house of Brunswick is firmly established upon the throne and that peace prevails in the land, it will become less easy for you every year to understand how men felt when Englishmen were in arms against Englishmen, and when he who should have been the shield and the protector of his subjects had no thought but to force upon them what they most abhorred and detested.

My story is one which you may well treasure up in your memories, and tell again to others, for it is not likely that in this whole county of Hampshire, or even perhaps in all England, there is another left alive who is so well able to speak from his own knowledge of these events, or who has played a more forward part in them. All that I know I shall endeavour soberly and in due order to put before you. I shall try to make these dead men quicken into life for your behoof, and to call back out of the mists of the past those scenes which were brisk enough in the acting, though they read so dully and so heavily in the pages of the worthy men who have set themselves to record them. Perchance my words, too, might, in the ears of strangers, seem to be but an old man’s gossip. To you, however, who know that these eyes which are looking at you looked also at the things which I describe, and that this hand has struck in for a good cause, it will, I know, be different. Bear in mind as you listen that it was your quarrel as well as our own in which we fought, and that if now you grow up to be free men in a free land, privileged to think or to pray as your consciences shall direct, you may thank God that you are reaping the harvest which your fathers sowed in blood and suffering when the Stuarts were on the throne.

I was born then in the year 1664, at Havant, which is a flourishing village a few miles from Portsmouth off the main London road, and there it was that I spent the greater part of my youth. It is now as it was then, a pleasant, healthy spot, with a hundred or more brick cottages scattered along in a single irregular street, each with its little garden in front, and maybe a fruit tree or two at the back. In the middle of the village stood the old church with the square tower, and the great sun-dial like a wrinkle upon its grey weather-blotched face. On the outskirts the Presbyterians had their chapel; but when the Act of Uniformity was passed, their good minister, Master Breckinridge, whose discourses had often crowded his rude benches while the comfortable pews of the church were empty, was cast into gaol, and his flock dispersed. As to the Independents, of whom my father was one, they also were under the ban of the law, but they attended conventicle at Emsworth, whither we would trudge, rain or shine, on every Sabbath morning. These meetings were broken up more than once, but the congregation was composed of such harmless folk, so well beloved and respected by their neighbours, that the peace officers came after a time to ignore them, and to let them worship in their own fashion. There were Papists, too, amongst us, who were compelled to go as far as Portsmouth for their Mass. Thus, you see, small as was our village, we were a fair miniature of the whole country, for we had our sects and our factions, which were all the more bitter for being confined in so narrow a compass.

My father, Joseph Clarke, was better known over the countryside by the name of Ironside Joe, for he had served in his youth in the Yaxley troop of Oliver Cromwell’s famous regiment of horse, and had preached so lustily and fought so stoutly that old Noll himself called him out of the ranks after the fight at Dunbar, and raised him to a cornetcy. It chanced, however, that having some little time later fallen into an argument with one of his troopers concerning the mystery of the Trinity, the man, who was a half-crazy zealot, smote my father across the face, a favour which he returned by a thrust from his broadsword, which sent his adversary to test in person the truth of his beliefs. In most armies it would have been conceded that my father was within his rights in punishing promptly so rank an act of mutiny, but the soldiers of Cromwell had so high a notion of their own importance and privileges, that they resented this summary justice upon their companion. A court-martial sat upon my father, and it is likely that he would have been offered up as a sacrifice to appease the angry soldiery, had not the Lord Protector interfered, and limited the punishment to dismissal from the army. Cornet Clarke was accordingly stripped of his buff coat and steel cap, and wandered down to Havant, where he settled into business as a leather merchant and tanner, thereby depriving Parliament of as trusty a soldier as ever drew blade in its service. Finding that he prospered in trade, he took as wife Mary Shepstone, a young Churchwoman, and I, Micah Clarke, was the first pledge of their union.

My father, as I remember him first, was tall and straight, with a great spread of shoulder and a mighty chest. His face was craggy and stern, with large harsh features, shaggy over-hanging brows, high-bridged fleshy nose, and a full-lipped mouth which tightened and set when he was angry. His grey eyes were piercing and soldier-like, yet I have seen them lighten up into a kindly and merry twinkle. His voice was the most tremendous and awe-inspiring that I have ever listened to. I can well believe what I have heard, that when he chanted the Hundredth Psalm as he rode down among the blue bonnets at Dunbar, the sound of him rose above the blare of trumpets and the crash of guns, like the deep roll of a breaking wave. Yet though he possessed every quality which was needed to raise him to distinction as an officer, he had thrown off his military habits when he returned to civil life. As he prospered and grew rich he might well have worn a sword, but instead he would ever bear a small copy of the Scriptures bound to his girdle, where other men hung their weapons. He was sober and measured in his speech, and it was seldom, even in the bosom of his own family, that he would speak of the scenes which he had taken part in, or of the great men, Fleetwood and Harrison, Blake and Ireton, Desborough and Lambert, some of whom had been simple troopers like himself when the troubles broke out. He was frugal in his eating, backward in drinking, and allowed himself no pleasures save three pipes a day of Oronooko tobacco, which he kept ever in a brown jar by the great wooden chair on the left-hand side of the mantelshelf.

Yet for all his self-restraint the old leaven would at times begin to work in him, and bring on fits of what his enemies would call fanaticism and his friends piety, though it must be confessed that this piety was prone to take a fierce and fiery shape. As I look back, one or two instances of that stand out so hard and clear in my recollection that they might be scenes which I had seen of late in the playhouse, instead of memories of my childhood more than threescore years ago, when the second Charles was on the throne.

The first of these occurred when I was so young that I can remember neither what went before nor what immediately after it. It stuck in my infant mind when other things slipped through it. We were all in the house one sultry summer evening, when there came a rattle of kettledrums and a clatter of hoofs, which brought my mother and my father to the door, she with me in her arms that I might have the better view. It was a regiment of horse on their way from Chichester to Portsmouth, with colours flying and band playing, making the bravest show that ever my youthful eyes had rested upon. With what wonder and admiration did I gaze at the sleek prancing steeds, the steel morions, the plumed hats of the officers, the scarfs and bandoliers. Never, I thought, had such a gallant company assembled, and I clapped my hands and cried out in my delight. My father smiled gravely, and took me from my mother’s arms. ‘Nay, lad,’ he said, ‘thou art a soldier’s son, and should have more judgment than to commend such a rabble as this. Canst thou not, child as thou art, see that their arms are ill-found, their stirrup-irons rusted, and their ranks without order or cohesion? Neither have they thrown out a troop in advance, as should even in times of peace be done, and their rear is straggling from here to Bedhampton. Yea,’ he continued, suddenly shaking his long arm at the troopers, and calling out to them, ‘ye are corn ripe for the sickle and waiting only for the reapers!’ Several of them reined up at this sudden out-flame. ‘Hit the crop-eared rascal over the pate, Jack!’ cried one to another, wheeling his horse round; but there was that in my father’s face which caused him to fall back into the ranks again with his purpose unfulfilled. The regiment jingled on down the road, and my mother laid her thin hands upon my father’s arm, and lulled with her pretty coaxing ways the sleeping devil which had stirred within him.

On another occasion which I can remember, about my seventh or eighth year, his wrath burst out with more dangerous effect. I was playing about him as he worked in the tanning-yard one spring afternoon, when in through the open doorway strutted two stately gentlemen, with gold facings to their coats and smart cockades at the side of their three-cornered hats. They were, as I afterwards understood, officers of the fleet who were passing through Havant, and seeing us at work in the yard, designed to ask us some question as to their route. The younger of the pair accosted my father and began his speech by a great clatter of words which were all High Dutch to me, though I now see that they were a string of such oaths as are common in the mouth of a sailor; though why the very men who are in most danger of appearing before the Almighty should go out of their way to insult Him, hath ever been a mystery to me. My father in a rough stern voice bade him speak with more reverence of sacred things, on which the pair of them gave tongue together, swearing tenfold worse than before, and calling my father a canting rogue and a smug-faced Presbytery Jack. What more they might have said I know not, for my father picked up the great roller wherewith he smoothed the leather, and dashing at them he brought it down on the side of one of their heads with such a swashing blow, that had it not been for his stiff hat the man would never have uttered oath again. As it was, he dropped like a log upon the stones of the yard, while his companion whipped out his rapier and made a vicious thrust; but my father, who was as active as he was strong, sprung aside, and bringing his cudgel down upon the outstretched arm of the officer, cracked it like the stem of a tobacco-pipe. This affair made no little stir, for it occurred at the time when those arch-liars, Oates, Bedloe, and Carstairs, were disturbing the public mind by their rumours of plots, and a rising of some sort was expected throughout the country. Within a few days all Hampshire was ringing with an account of the malcontent tanner of Havant, who had broken the head and the arm of two of his Majesty’s servants. An inquiry showed, however, that there was no treasonable meaning in the matter, and the officers having confessed that the first words came from them, the Justices contented themselves with imposing a fine upon my father, and binding him over to keep the peace for a period of six months.

I tell you these incidents that you may have an idea of the fierce and earnest religion which filled not only your own ancestor, but most of those men who were trained in the parliamentary armies. In many ways they were more like those fanatic Saracens, who believe in conversion by the sword, than the followers of a Christian creed. Yet they have this great merit, that their own lives were for the most part clean and commendable, for they rigidly adhered themselves to those laws which they would gladly have forced at the sword’s point upon others. It is true that among so many there were some whose piety was a shell for their ambition, and others who practised in secret what they denounced in public, but no cause however good is free from such hypocritical parasites. That the greater part of the saints, as they termed themselves, were men of sober and God-fearing lives, may be shown by the fact that, after the disbanding of the army of the Commonwealth, the old soldiers flocked into trade throughout the country, and made their mark wherever they went by their industry and worth. There is many a wealthy business house now in England which can trace its rise to the thrift and honesty of some simple pikeman of Ireton or Cromwell.