Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

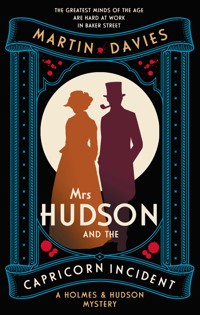

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Holmes & Hudson Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

It is spring in Baker Street, and London is preparing itself for the wedding of the year. It will be an international spectacle in which the young and popular Count Rudolph Absberg, a political exile from his native land, will take the hand of the beautiful and accomplished Princess Sophia Kubinova. A lot depends on the marriage, for it is hoped that the union will ensure the security and independence of their homeland. When the princess subsequently disappears in dramatic circumstances, members of the British establishment are quick to call on Mr Sherlock Holmes. He, in turn, needs the gifts of long-standing housekeeper Mrs Hudson and her able assistant, housemaid Flotsam, to solve this puzzling case on which rests the fate of nations. The continuation of the intricately crafted Holmes & Hudson series is a treat for fans of the great detective's original cases while they offer an inspired take on the rest of the famous Baker Street household.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

MRS HUDSON AND THE CAPRICORN INCIDENT

MARTIN DAVIES

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

London, May 1951

It’s easy not to notice how quickly London changes. So much of it is old and seems so permanent. But its avenues and alleyways are constantly renewing themselves, putting on new faces. Shops open and close, fashions alter, and the names in lights above the theatre doors are taken down and replaced with those of newer stars.

Yesterday I dined in a very fine restaurant not far from Somerset House. I was the guest of a former student, now an eminent academic at a university overseas, who talked at length about how good it felt to be home for a few days, to wander along Aldwych and up Drury Lane, to hear the rumble of lorries and the roar of the traffic, and feel himself back in old, familiar London.

I smiled and let him talk. He’s a clever and good-hearted young man, and it’s kind of him to spend an evening with an old lady like me. I felt no need to tell him I could recall a very different London, where there had been no Aldwych, where in its place there had been a tangle of seedy alleyways and dark courts, as grim and as dangerous as anything from Dickens. No need for him to know that only a few yards from the spot where we sipped our wine, I’d once stood in candlelight, in a 6smoke-blackened backroom off a stinking alleyway, surrounded by strangers, feeling certain those flickering candles would be the last lights I’d ever see.

Before we left the restaurant, while he settled the bill, I shut my eyes for a moment. Even after such a long time, if I listened carefully it wasn’t impossible to make out, behind the clinking glasses, the rattle of hansom cabs; strangely easy to see myself stepping out over cobbles with a bounce in my stride, on a bright May morning more than fifty years before…

CHAPTER ONE

Spring came late to London that year.

All through March and well into April a bitter east wind scoured the streets, numbing the fingers of the flower girls and mocking their little posies of daffodils and forget-me-nots. In the windows of the big shops, the displays of bright walking-costumes and fresh spring bonnets looked forlornly out of season, and on the Serpentine, the little rowing boats, which came out in time for Easter every year without fail, had all been hastily stowed away again to protect their fresh paint and polished brasses from the elements. Even by St George’s Day, the cabbies on their hansoms remained grimly gloved and muffled.

And then, quite suddenly, one morning in early May, winter was gone. Its hasty retreat took the city unawares, trapping its inhabitants under far too many warm layers, so that for one awkward afternoon even the most proper pedestrians could be seen dabbing and mopping, and perspiring far too freely, and smart ladies in furs began to turn an alarming shade of pink.

I remember that day well because I had ventured out especially early, in my warmest winter petticoats and thickest skirt, determined not to be fooled by the blue skies that for weeks had been promising a warmth they utterly failed to 8deliver. It was the day when Scraggs, the grocer’s boy, was leaving for the north – although, of course, by then he wasn’t actually a grocer’s boy any more, or indeed any sort of boy at all, but a tall and rather pleasing-looking young man, and the part-owner of a successful London store.

We were very old friends. When I’d first encountered him he had been a boy selling goods from a barrow, on a foggy night still vivid in my memory. I had been a homeless and desperate fugitive, perhaps a year or so younger than he was, and he had guided me towards refuge. So, yes, we were certainly old friends. And if more recently, when people mentioned his name to me, I would sometimes blush a little; and if from time to time, when I had a break from my chores, I would find him waiting for me by the area steps so we could walk together in the park; and if, on that particular morning, I thought I might make a little diversion by way of St Pancras station to see him off … Well, it didn’t do to dwell on such matters, not when life was so busy and there was so much to get done.

Even so, I admit I might have rushed things a little that morning. I certainly walked everywhere rather quickly, and had to bite my lip when old Mr Musgrave spent such a very long time weighing out the rice. I might even have run a few steps, just on the way into the station, to be sure I was there in time to say goodbye.

It wasn’t until after that – after I’d said my farewells and waved off the train, just as I was stepping out of the shadow of St Pancras – that the wind dropped, and a stillness descended, and for the first time that year I felt the warmth of the sun on my cheeks. By the time I was halfway to Baker Street, I was already uncomfortably hot, and my petticoats had begun to 9cling to my legs in a most unladylike manner.

Nevertheless, there was nothing for it but to hurry home despite the stickiness; I had chores to complete and a floor to scrub, and there really was no excuse for moping around on train platforms, not when the stair-rods were in such urgent need of dipping.

But somewhere on the other side of the park, church bells were ringing, and on the corner of Wimpole Street the newsboy’s cries seemed strangely in tune with their peals.

‘Fairy-tale wedding brought forward!’ he called cheerfully. ‘Read all about it! Read all about it!’

Looking back, it seems strange how little notice I took. Instead I paused to shrug off my heavy coat, and then hurried onwards with it bundled clumsily over my arm. I had things to do – and if perhaps there was something weighing on my mind as I made my way home that day, it was nothing to do with fairy-tale weddings.

The first warm breath of spring did little to lift the mood of my employer, Mr Sherlock Holmes. The final day of April had been a momentous one – the day the great detective revealed to the world the solution of the Seven Otters Mystery, a case so demanding mentally and so exhausting physically that for almost a week afterwards Mr Holmes and Dr Watson barely stirred from their beds. As was often the case after a particularly draining engagement, a period of recuperation was followed by a spell of lassitude and low spirits, and it was just such a mood that prevailed in Baker Street that day. In Mr Holmes, it manifested itself in much staring out of the window and some listless playing of the violin; in Dr Watson, it took a rather 10different form. He had become oddly fretful, as if struggling to remember how he had previously filled his days – constantly taking up his stick and gloves as if to set out on a good walk, then putting them down again and pouring himself a measure of brandy and shrub instead.

Downstairs, however, things remained as calm and serene as ever, and I found Mrs Hudson waiting for me in the kitchen, with a jug of spiced lemon water on the kitchen table and a Shrewsbury biscuit on a saucer next to it.

‘Because it occurred to me, Flotsam,’ she explained briskly, ‘that anyone out and about today in a coat as thick as yours must be in need of a cold drink. Especially if they happened to have come home by way of St Pancras.’

Mrs Hudson’s reputation for excellent housekeeping and for sound common sense had long been recognised in servants’ halls well beyond Baker Street, and on the fateful night when Scraggs had found me weeping in a gutter in barely enough rags to cover me, it had been to Mrs Hudson that he’d brought me – a decision that changed my life so utterly that my previous existence seems strange and indistinct to me now, as though all those ordeals were part of a dimly remembered story lived by someone else.

Under Mrs Hudson’s stern eye, I had been transformed in a surprisingly short time from a homeless orphan to a neat and tidy housemaid; and not content with teaching me the correct way to mop a floor and to polish silver, she insisted on all sorts of other education too, employing an array of acquaintances to tutor me in subjects not generally considered necessary, or indeed suitable, for housemaids. To my great surprise, I found myself learning Latin from the Irish knife grinder and 11French from a succession of different ladies’ maids. The task of teaching mathematics fell to the local costermonger; and history to various ancient butlers who, I often thought, must have witnessed a great deal of it personally. Before long, I had read every book I could find in Baker Street, and an elderly neighbour’s collection of novels from the previous century had been devoured with such appetite that a subscription was obtained for me at Mudie’s library.

‘You see, Flotsam,’ Mrs Hudson would tell me, if I ever questioned the need for Latin verbs or algebra or capital cities, ‘without an education a young girl is trapped below stairs as surely as if she were tethered to the broom cupboard. And there will always be plenty of people out there in the world who are certain they know much more about everything than you do. So it’s important that you, at least, know otherwise.’

The kitchen at Baker Street was below street level and remained pleasantly cool even during the hottest summers. That day it felt like a welcome refuge from the unexpected stickiness of the streets, and I discarded my coat without ceremony, then wriggled free from two further layers of wool, before falling upon the lemon water in a slightly improper state of undress. As I drank, Mrs Hudson rolled up her sleeves and began to wipe down the stove, her roundly muscled arms moving rhythmically, in long, even strokes.

‘So, tell me, young lady, did you in fact manage to say goodbye to Scraggs?’ she asked as she worked.

I told her that I had, and that he sent her his regards, and would send a note when he knew the date and time of his return – just in case, I conjectured casually, either of us felt inclined to meet his train. 12

‘But until then, ma’am, he’ll be a great deal too busy to write,’ I told her decidedly, ‘what with all his business meetings and things. And I suppose he’ll be out a great deal in the evenings, what with all the music halls and theatres up there. They say Vesta Tilley is performing in Manchester at the moment, and I know Scraggs is a great admirer of hers, so I imagine he’ll go to see her more than once. And there’ll be all sorts of different plays on too, and I imagine there’ll be a great many people wanting to spend time with him whenever he has a moment to spare.’

Mrs Hudson listened to this solemnly, her gaze firmly on the stove, and if I’d been secretly hoping that she might contradict me at least a little bit, I was to be disappointed, because any reply she intended to make was cut off by the jangling of the study bell.

‘That will be Mr Holmes again,’ she told me with a sigh, ‘and this time he’ll be impatient for the afternoon post. You had better take it up, Flotsam – it’s over there, by the door, so do up some buttons and find a clean apron, and jump to it. And let’s keep our fingers crossed that there’s something in those letters to interest the two gentlemen, or to get them out of the house for an hour or two at the very least. Because if you and I don’t have an opportunity to give that room a proper clean in the next day or so, Flottie, it won’t be Turkish jugglers or one-eyed publicans or dishonest dukes they’ll be worrying about this month, it will be rats.’

I found Mr Holmes pacing listlessly in front of the fireplace in the study, while Dr Watson watched him glumly from his armchair, a crumpled copy of The Times lying discarded at his feet. 13

‘Well, I’m dashed if I can find anything there to interest us,’ I heard him saying as I entered the room. ‘Only the latest on the hunt for Mrs Whitfield, the fraudster, the one who tricked the Count of Ferrara out of £10,000 in Monte Carlo last February. A few days ago Inspector Lestrade was telling me she’s still in America, but now the New York police are saying she sailed for Europe in May under the name Madame Emma St Aubert. Left her six Siamese cats behind, apparently, in the care of a one-armed Irish butler, which is why they didn’t notice till now.’

‘She has made fools of cleverer men than Lestrade, Watson,’ his friend observed loftily. ‘I like to think, however, should she ever be foolish enough to return to these shores, I could run her to ground in no more than a day. Two at most. Every great criminal has their flaws.’

‘Well, Holmes, apart from Mrs Whitfield, it’s just the usual litany of pub brawls and domestic shenanigans. Most of the column space is taken up with talk about this Rosenau wedding.’

‘Wedding?’ Mr Holmes seemed unimpressed. ‘Oh, yes. A minor affair, diplomatically speaking, but no doubt of interest to readers of magazines and the makers of expensive hats. Ah, Flotsam! Come in, come in. You have the post?’

He paused in his pacing but remained by the fireplace, signalling with a wave of his unlit pipe that I should take the tray to his friend. The fire in the study had been allowed to die down, but the sun was streaming through the open shutters, filling the room with a pleasant, golden light. Even so, with the windows closed it was perhaps a trifle stuffy, and as I placed the letter tray next to Dr Watson I couldn’t help but notice 14a distressing quantity of crumbs on the arm of his chair and rather more on the floor below. Mrs Hudson was quite right to think that a good clean was in order.

The doctor eyed the large pile of letters with enthusiasm.

‘It’s a good haul, and no mistake. Must be something for us here, eh, Holmes? Will you take a bundle for yourself?’

But his friend dismissed this suggestion with another swirl of his pipe.

‘You know how greatly most of our mail irritates me, Watson. When you have discarded the banal, the tedious and the frankly witless, we shall be lucky if we are left with even one piece of correspondence worthy of our attention. No, my friend, you shall read and I shall listen. But by all means feel free to give my share of the pile to Flotsam here, if you think that will help. She is generally less easily shocked than you are by some of our seedier correspondence.’

In any other house, in any street, in any city in England, a housemaid would have been astonished – and not a little alarmed – to hear such a suggestion being made, but I had long since understood that Mr Holmes was not a man to be governed by convention. Indeed, once he’d realised that I could open a letter, and read it, and make sense of its contents, he had been more than willing to put me to work in such a way whenever it added to his convenience. To the great detective, a quick mind was more important than good birth, and efficiency was everything. He would have had the ironmonger make his breakfast and the coalman wash his sheets if he thought either of those things would help solve a puzzle or assist him in bringing a criminal to justice.

So I made no protest, but seated myself in my employer’s 15armchair as directed, and meekly accepted a dozen or more crisp envelopes from Dr Watson. And of course any protestation on my part would have been a terrible falsehood, because I was thrilled to be employed in such a way, partly because each fresh envelope held the promise of a new mystery or a new puzzle, and partly because reading the post of Britain’s most famous detective was a great deal more enjoyable than dipping the stair-rods.

Even so, it was hard not to be a little disappointed by most of the letters I opened. As Mr Holmes had predicted, a great many of them concerned the most trivial things imaginable, and those that did not were quite simply rather odd. Judging by the grunts from the seat next to mine, Dr Watson was experiencing similar frustrations.

‘Good Lord, Holmes! This one here is from a man whose cat has developed a strange rash from walking through his neighbour’s onion patch. And there was another about a dog with a limp. It beats me why so many people mistake you for a veterinarian! Are you having any better luck, Flotsam?’

I confessed that I wasn’t. ‘There’s the usual letter from the lady in Cornwall, sir, the one who believes the Bishop of Truro has been kidnapped and replaced by an impostor. And one from a lady south of the river who is suspicious of her new neighbour’s gloves, which she considers to be too fine to be respectable. They have led her to conclude that the lady in question must in fact be a fallen woman of the worst kind, and that her so-called husband, far from being a dealer in woollen goods, must really be a disreputable aristocrat in disguise.’

Dr Watson chuckled. ‘We should introduce her to this gentleman here, who claims to have irrefutable evidence that 16his neighbour is the Buxton Forger, even though it’s at least two years since old Templeton was found with the press in his cellar and a barrel full of notes in the garden, and confessed to everything.’

And so it went on until there were only two envelopes left. The last letter I opened, a missive in violet ink on thick, creamy writing paper, was written in an elegant and feminine hand. It was little more than a note, really, and my eye quickly reached the signature at the bottom.

‘Why!’ I exclaimed. ‘This one is from Miss Mabel Love!’

Mr Holmes fixed me with that stern gaze of his, as if waiting for an explanation, and I found myself flushing, a little embarrassed by my own enthusiasm.

‘Popular actress, Holmes,’ Dr Watson explained, gently taking the letter from my hand so that he could study it more closely. ‘Romances and comedies and whatnot. I believe she’s all the rage at the moment, is she not, Flotsam?’

‘Yes, sir. She’s much admired. She dances too, and everyone was talking about how good she was in her pantomime over Christmas. She’s supposed to be very beautiful.’

‘Let’s see …’ Dr Watson continued to peruse the letter. ‘She asks if you could call on her, Holmes, about a matter causing her considerable anxiety. Doesn’t say what, though. Still, it’s a very courteous letter.’

But Mr Holmes was unimpressed, and I could see his gaze drifting towards the window. The energy that had animated him briefly upon the arrival of the post was ebbing from him now, and I resigned myself to an evening of much mournful violin music.

‘Really, Watson,’ he sighed. ‘The fact that this lady is a 17prominent and reputedly comely thespian clearly prejudices you in her favour, because there is nothing in her note to suggest that her particular anxiety is any more substantial, or any less fanciful, than those of our other correspondents. Still, you may call upon her if you wish. And be sure to take Flotsam with you.’

‘You feel I will need assistance, Holmes?’ The good doctor looked somewhat nettled.

‘On the contrary, my dear fellow, I know you to be more than capable of holding a conversation with an attractive woman without any assistance whatsoever. But judging from the colour in Flotsam’s cheeks, and by the way her usually very sensible voice became strangely idiotic when speaking the lady’s name, I conclude that an invitation to call on Miss Mabel Love would be very much to her liking. Now, if we have finished …’

‘Not quite, Holmes,’ the doctor corrected him. ‘There’s still one more.’

He sliced open the final envelope with a flourish of his paper-knife, and pulled from it a sheet of thin, densely written writing paper. As he did so, a small newspaper cutting fluttered to the carpet, and I leant forward in my chair to pick it up.

CHESTER TRAIN MYSTERY

A sensation was caused at Chester General station last evening on the arrival of the 3.30 p.m. train from Llandudno by the discovery, underneath the seat of a first-class carriage, of a lady’s dressing case. On the seat of the carriage were a lady’s hat, coat and satchel, all of very good quality. No person came forward to claim these items, and 18found with them was a hand-written note of a tragical and desperate nature. A search party was dispatched along the line, but failed to find any body.

Dr Watson took it from me, ran an eye over it, then returned to the letter.

‘It’s from an Inspector Hughes of the Flintshire Constabulary,’ he told us. ‘He’s asking permission to travel to London to consult you, Holmes. Seems a woman’s disappeared. And I don’t mean gone missing. From what Hughes writes here, he seems to think she has quite literally vanished into thin air.’

These words had a very noticeable effect upon my employer. It wasn’t so much that he changed his position – he remained leaning nonchalantly against the mantelpiece – but something in his face or in his eyes was altered, and I could tell that his attention, which had been so obviously wandering, was now fixed fully upon his friend.

‘And, Holmes, before you tell me that Inspector Hughes must be some ignorant country policeman with an over-active imagination, you should read his letter. He takes pains to place four incontrovertible facts before you.

‘Firstly, that the woman in question was helped into an empty first-class compartment at Llandudno station just moments before the train pulled away. Secondly, that she did not leave the train at Chester station, where it terminated, nor at any of the stations in between. Thirdly, that searchers found no traces of the woman on the train itself at Chester, nor of any corpse along the tracks. And fourthly, that it was impossible for anyone to have jumped or fallen from the train while it was in 19motion without leaving traces of such an action behind them.’

Outside, the warm spring sunshine still pressed against the windows, and now, finally, something of its reviving brightness seemed to have reached the occupants of the room. Mr Holmes still hadn’t changed his position, and his gaze was focused very intently on his pipe, but I could almost feel the intensity of his concentration, and perhaps even a sort of underlying joy at once again having a problem worth engaging with.

When, after a few more seconds, he did move from the mantelpiece, it was to take the letter and cutting from his friend. He read them in silence, nodding as he did so.

‘This cutting is dated only three days ago,’ he remarked when his examination was complete, ‘and the letter was written yesterday, so the inspector has wasted little time in contacting us. Which suggests, of course, that he is either hasty in his work, or that he is an unusually thorough man, and one who has understood with commendable alacrity the point at which traditional police methods have run their course.’

He lowered the papers for a moment and appeared to fix his gaze instead on an unfortunate burn mark on the opposite wall, one caused some months previously by a misguided experiment with Chilean saltpetre.

‘Let’s see … That line runs along the coast of North Wales …’

He considered for a moment.

‘We must reply to the inspector at once and urge him to call upon us without delay. Until he does, we simply do not have sufficient information to draw any firm conclusions.’ I watched him pause for a moment, the trace of a smile playing on his lips. ‘But I rather assume, Watson, that when we meet 20Inspector Hughes, if he is the competent fellow his letter suggests, that he will be able to confirm three significant pieces of information.’

‘And what are they, Holmes?’

‘Why, that the missing woman was somewhat taller than average. That on the afternoon in question, a strong wind was blowing across the Irish Sea. And that one of the search parties sent out to look for her body has discovered, or will discover, in a rural location and around twelve yards from the track, a pair of discarded boots in very good condition.’

‘But, Holmes!’ Dr Watson rose and took the letter from his friend’s hand, as if to check it was the same document. ‘You cannot possibly expect us to believe that you have discovered any of those things from the inspector’s letter?’

‘I don’t expect you to believe anything at all at this point, my friend, and yet I’ll wager I’m not far out. I think, to speed things up, a telegram is in order. Perhaps you would be good enough to wire Inspector Hughes this afternoon, Watson? And I suppose a note to Miss Mabel Love would be appropriate. As for the others, when time allows, perhaps the usual response. I have no doubt that Flotsam here will help with the correspondence. And now some sandwiches, I think, Flotsam, if you would be so kind. And perhaps a bottle of brown ale. We have maps to look at and railway timetables to study, and I feel a thirst coming on.’

It was good to see Mr Holmes in high spirits once more, and if he occasionally mistook me for a secretary instead of a housemaid, it was an error I was more than happy to leave uncorrected. I carried the tray downstairs that day pleased that the two gentlemen were finally occupied, and content that Mrs 21Hudson and I would be able to get to work on the stair-rods without any accompaniment from Mr Holmes’s violin.

But if I had learnt any lesson from my time in Baker Street, it was that a quiet afternoon was rarely followed by a quiet evening. It was nearly ten o’clock when our peace was shattered by a crisp, sharp rapping on the front door, and I found myself face to face with an elderly gentleman of ample proportions wearing the most extraordinary military uniform I’d ever seen, a disturbing confusion of scarlet and purple and gold, with a row of enormous medals pinned across the chest, and epaulettes so huge it looked as though he were trying to sprout wings. Behind him, in the empty street, stood an ornate carriage guarded by two footmen, their livery so colourful and exotic that they seemed to have stumbled out of a May Day pageant.

But those weren’t even the first things I noticed about our caller.

The first thing I noticed was that he looked white as a sheet.

CHAPTER TWO

General Septimus Octavian Nuno Pellinsky, Count of Kosadam, Hereditary Guardian of the Monks of St Stephen and Adjutant General to the House of Capricorn, had almost as many titles on his card as he had brass buttons on his uniform, and he was shown into Mr Holmes’s study with all the promptitude his dramatic presence seemed to demand. As well as that dazzling array of colours, he carried with him a strong scent of pipe tobacco, a hint of fashionable cologne and an undeniable air of grandeur. I have ushered more than one great statesman into Mr Holmes’s presence, as well as some of the highest-ranking lords and ladies in the land, but there’s no denying that few of them filled the room in quite the same way as General Pellinsky.

It was perhaps something of a relief to me that my employers seemed no less startled than I had been by the appearance of our visitor. Dr Watson, clearly taken aback by such great quantities of ribbon and braid, rose hastily from his armchair and for the briefest of moments appeared ready to stand to attention; and even Mr Holmes, though less obviously inclined to salute, lowered his pipe to his waist and noticeably hesitated before offering the usual words of welcome. 23

Introductions followed, however, and the general was offered a seat, then whisky and tobacco, and was made as comfortable as possible in an armchair slightly too small for him. Once I had moved the drinks tray closer to Dr Watson, there was no excuse for me to linger, so I bobbed a little curtsy and retreated, taking with me an empty beer bottle hastily retrieved from one end of the mantelpiece and some screwed-up pages of The Times, which Dr Watson, to amuse himself, had been shying at the wastepaper basket. No room containing General Pellinsky ever really looked tidy, though; his great frame still sat awkwardly in its seat, and his uniform clashed with the rug.

I didn’t retreat very far. My chores were done for the day, but there was no prospect of going to bed while our guest remained in the house, and little point in making myself too comfortable downstairs when the bell might summon me back at any minute. So instead of joining Mrs Hudson, who was writing letters at the kitchen table next to a rather fine glass of port, I retired to the silver cupboard, where there were always knives to polish and spoons to put away, and where a large, engraved plate of dubious taste, presented to Mr Holmes by the grateful son of an anxious archbishop, was sadly tarnished and awaiting some attention.

I must confess, however, that I was not entirely motivated by an urge to polish cutlery. The silver cupboard was not really a cupboard at all, but a very small room lined with deep shelves, and there was just enough space in there for a diligent housemaid who tucked in her elbows to get to work with a soft cloth. It also happened to be directly opposite Mr Holmes’s study, and positioned in such a way that if the study door was left only a 24little open, and if the door of the silver cupboard was not quite closed, anyone engaging with the soup spoons was afforded a surprisingly clear view into the other room. In addition, voices carried quite clearly between the two rooms, so that a young girl going about her chores in one couldn’t help but overhear a great deal of what was said in the other.

In my defence, it hadn’t taken my employer very long to discover this acoustic anomaly, and yet he had never seemed greatly exercised by it. While his visitors would no doubt have been appalled by the idea that their discussions might be overheard, Mr Holmes seemed to find a certain wry amusement in the possibility, believing firmly that the better Mrs Hudson and I understood his activities and requirements, the more efficiently we could cater to his needs. To Mr Holmes, discretion and confidentiality were quite different things, and I had seen for myself that clients were prepared to overlook a great many eccentricities if they contributed to a satisfactory outcome.

Whether or not General Pellinsky was one such client was hard to say, but his pale demeanour, and the distress in his voice, suggested that he was in no mood to quibble about the great detective’s unusual domestic habits. When he spoke, it was in the slightly too perfect English of one who is not a native speaker.

‘You will forgive me, sir …’ he began, and the words seemed to tremble a little. ‘You will forgive me for this untimely intrusion. Had it been possible, I would have deferred my visit until tomorrow, and to a more suitable hour. But, alas, duty dictates that I should lay this matter before you with the greatest urgency. Not a moment is to be lost. The situation I have discovered is … It is simply … Well, I can assure you, 25Mr Holmes, that if something is not done, and done quickly, my homeland faces utter humiliation and abject ruin, with consequences that will be felt – and deeply felt – from Vienna to St Petersburg, and even on these very shores.’

He paused as if for breath, and I heard Mr Holmes give that little click of his tongue that always betrayed his impatience.

‘Perhaps, General, you would be good enough to confirm for us precisely which homeland you refer to? Your card refers to the House of Capricorn, which I believe still rules over the Grand Duchy of Rosenau, but I confess your uniform confounds my knowledge of middle European military attire. I can tell only that you have travelled here today by way of Paris, where you first got wind of certain information. That information caused you to abandon an official engagement that had long been in your diary in order to travel to London with the greatest dispatch. Upon arrival here, you hastened to your consulate, where you were able to obtain further information – information that alarmed you so greatly that you felt obliged to call here without delay.’

Mr Holmes paused for the briefest of moments, as if to order his thoughts.

‘As for the cause of your perturbation, I can only speculate. But as the newspapers here are devoting an irresponsible amount of space to the forthcoming nuptials of the Rosenau heir, and as his marriage is considered vital to the future stability of the Grand Duchy, I assume that some obstacle has been discovered that might prevent the much-anticipated wedding from taking place. Am I right?’

It was, of course, not the first time I had known Mr Sherlock Holmes greet a visitor in such a way, but I confess that it still gave 26me a little thrill to hear it. Certainly, the effect of this speech on General Pellinsky did not disappoint, for that gentleman simply gaped for a full five seconds, then wiped his brow with a braided cuff and cleared his throat rather noisily.

‘I cannot begin to fathom how you have divined so much from my presence here tonight, Mr Holmes, but you are absolutely correct in almost every particular. You are, however, wrong in one crucial detail. No obstacle to the forthcoming nuptials has been discovered. It is still the will of the Archduke, and the expectation of the people, that the wedding should take place. Indeed, a great deal depends upon it. And if you have read the newspapers today, you will know that the date has been brought forward at the insistence of the Archduke himself, to precisely ten days’ time.’

‘We have read that, haven’t we, Holmes?’ Dr Watson confirmed sagely, his empty glass cradled gently in his hand. ‘Seems to be a great deal of excitement about it. You know, handsome foreign nobleman, beautiful foreign princess and all that. Childhood sweethearts, feuding factions united, and all of it taking place at a secret venue somewhere in the Home Counties. Just the sort of thing to appeal to the British public! But tell me, General, if no obstacle has arisen to prevent true love running its course, then what brings you here tonight?’

‘That, sir, is what I am about to explain.’

The visitor took a deep breath and cleared his throat for a second time.

‘You see, Doctor,’ he went on, and even from where I was standing I could see his pale cheeks flush as he spoke. ‘You see, Doctor, it appears we’ve managed to mislay the bridegroom.’ 27

At that hour of the night, the street outside was quiet, with few pedestrians and little traffic. In the brief silence that followed General Pellinsky’s dramatic utterance, I could hear the hoof-falls of a single dray horse plodding beneath the study window.

The silence in the room was broken by the sound of Mr Holmes rapping his pipe sharply against the mantelpiece, an action that I believe betrayed a degree of interest, since I knew for certain that his pipe was already quite clean of tobacco. The sound seemed to rouse Dr Watson, who rose from his armchair and stepped to the drinks tray, refilling the general’s glass as well as his own. It was as if the bald statement of our visitor’s problem had in some way broken the tension, and when Mr Holmes spoke, he sounded completely at ease.

‘Perhaps, General, if you were to tell your story from the beginning. The Grand Duchy of Rosenau is, I believe, one of those semi-independent states that have survived in various parts of the Balkans despite the recent upheavals?’

‘That is correct, sir.’

The general too seemed to have relaxed slightly, as though the confession of his difficulty had already lifted a little of the weight from his shoulders. He nestled deeper into his chair, took a deep breath and began to tell his tale.

‘Gentlemen, there has been a member of the House of Capricorn ruling in Rosenau since Rudolph the Valiant freed the town from Ottoman rule in the early eighteenth century. Although nowadays we style Rosenau a city – its cathedral is a fine and elegant building – it is, by the standards of your own country, no more than a modest if prosperous town, and as you suggested, Mr Holmes, its independence is more theoretical than real. The position of the Archduke is in many ways simply 28a pleasing anachronism in an increasingly perilous world.

‘Nevertheless, Mr Holmes, and I cannot stress this strongly enough, Rosenau is not without political and strategic significance, and it is the dangers arising from this that have led us into our current difficulties. As you may be aware, the town is evenly divided between German-speaking and Slavic citizens, and while the townsfolk themselves have lived in harmony with one another for centuries, there are certain groups and individuals who wish to fly their flag over Rosenau as part of a much wider struggle.’

General Pellinsky gave a little sigh – a surprisingly meek and mournful sound from such an imperious figure – and wiped his brow again before continuing.

‘Certain nationalist groups within the Hapsburg Empire would like nothing better than to see Rosenau take its place as part of a wider community of German-speaking states. Equally, a secret society inspired by radicals in Serbia see Rosenau as part of a wider Orthodox brotherhood, and is constantly plotting to abolish the duchy and merge it with its Slavic neighbours. Austria, of course, is broadly supportive of the former group, Russia of the latter, but both those nations are content so long as the ambitions of the other show no signs of bearing fruit.’

‘Tricky balancing act, eh?’ Dr Watson put in, nodding wisely. ‘And presumably a bit precarious?’

‘Indeed, sir. That balance has been successfully maintained for all these years largely through the House of Capricorn’s clever use of marriage. As the saying goes, Rosenau is defended not by battalions but by wedding breakfasts. I fear the phrase loses something of its cleverness in translation. Suffice it to say, the current Archduke, Quintus, is of German heritage through 29his father’s side, but his mother was a Slovene, and while the Archduke lives the balance is maintained.’

Mr Holmes said nothing, but Dr Watson was clearly enjoying this foray into dynastic manoeuvrings.

‘Quintus … Let me see … I think I read an article about him a few years back. Getting on a bit now, isn’t he?’

‘The Archduke is in rude health for a man of his age,’ General Pellinsky replied rather coldly, ‘but he is seventy-three years old, and none of his predecessors lived beyond the age of sixty. And significantly, he has no direct heir. His younger brother, who was expected to inherit the title, suffered a fatal stroke two weeks before Christmas, in a private box at the Folies Bergère. As a result, were the Archduke to die tomorrow, his passing would spark a constitutional crisis and would herald the downfall of the House of Capricorn.’

Mr Holmes, still in his favourite spot by the mantelpiece, raised an eyebrow at this. ‘How so? Even if the Archduke has no children, he must have other heirs.’

‘My thought exactly,’ Dr Watson agreed. ‘If you’ll forgive me for saying so, General, it all seems a bit melodramatic. The downfall of whatnot sounds like something out of a cheap novel, and not a very good one at that.’

The general puffed out his cheeks as if in an effort to remain calm. ‘I will not trouble you gentlemen with a detailed explanation of the constitutional arrangements pertaining to the Grand Duchy,’ he told them. ‘They are undeniably complex, and to the British public must seem every bit as fanciful as any of those Ruritanian fantasies that are currently so popular in your theatres. I shall simply say that the only viable heir to the Archduke’s title is the young Count Rudolph Absberg, whose 30wedding is due to take place in just over a week’s time.’

‘And whose whereabouts are now unknown?’ Mr Holmes did not seem displeased to discover that more was at stake than a wasted wedding feast.

‘Yes, sir. And that ceremony must take place. You see, Count Rudolph cannot succeed the Archduke unless he is married within six months of becoming the heir to the title, and married to the eldest daughter of one of the duchy’s pre-eminent Slavic families – in this case, precedent demands that it can only be the Princess Sophia Kubinova. The “princess” is purely an honorary title, you understand, traditionally bestowed upon the young woman first in line to marry the heir to the duchy.’

Dr Watson was pursing his lips. ‘I confess it is a little complicated, isn’t it, Holmes?’

‘On the contrary, Watson. Stated simply, Rosenau will cease to exist as an independent entity unless those two young people marry within the next month. If they do not, there is no heir, and the Archduke’s death when it comes will inevitably ignite a dangerous confrontation between two of Europe’s great powers. Is that a fair summary, General?’

Our visitor was nodding, and I couldn’t help but notice that every nod of his head made his epaulettes shake a little.

‘Very fair, Mr Holmes. Unfortunately, Archduke Quintus is not an even-tempered man. In fact he is the opposite, and there are few important families in Rosenau with whom he has not fallen out at one time or another. As a result, both Count Rudolph and the Princess Sophia have lived most of their lives in exile, while in Rosenau the Archduke conducts an unfortunate series of scandalous affairs with unsuitable women, the latest, I believe, being with an American widow 31not a great deal older than the Princess herself. The Count and the Princess have known each other since childhood, of course, and are excellent friends, and it is widely believed that their marriage was but a matter of time. But the death of the Archduke’s brother has left them with no choice but to marry by the eleventh of June, for the sake of their homeland.’

Dr Watson grunted. ‘Haven’t I heard that this Rudolph fellow spends most of his time over here?’

‘That’s right, Doctor. Count Rudolph is a confirmed Anglophile and keeps a hunting lodge in Sussex where he spends a very substantial part of every year. Princess Sophia attended a private school in Kent, but has lived for the last two years mostly in Paris and Antibes. After his brother’s death, the Archduke decreed that the wedding must take place within the required time frame, but as he had no intention of paying for it, he agreed to the couple’s request that it should be a private affair here in England.’ The general blushed slightly. ‘I believe his actual words were, “They can marry down a blasted coalmine for all I care, so long as I have an heir.”’

He paused and took a modest sip from his glass of whisky. ‘Now, the young couple are a pleasing pair who both understand their duty. They also understand that those radical groups I spoke of earlier would be more than delighted if their wedding did not take place. Therefore, as a precaution, it was agreed Princess Sophia would leave her apartments in a rather bohemian part of Paris and, for the weeks before the wedding, take up residence with her godmother, Lady Harby, in Eaton Square, where her safety might be more easily ensured. Count Rudolph asked permission to undertake a tour of the Alps before his marriage, and it was agreed that he could do so if 32it were done incognito. It seemed to me, Mr Holmes, that allowing him to disappear into the mountains was as good a way as any of making him invisible to a would-be assassin.’

Even from my slightly cramped position in the silver cupboard, I could see Dr Watson’s face brighten with a look of understanding.

‘Disappear into the mountains, you say? And now he has disappeared into the mountains, and you need us to find him?’

But General Pellinsky shook his head. ‘Not quite, Doctor. It was agreed that he would set out in early January, with a certain Captain Christophers, his closest friend, as his companion. Both young men are keen on winter sports, so we agreed a strict itinerary, meaning that I could contact them instantly if necessary, and Count Rudolph gave me his word that he would be here in London in early May, in plenty of time for the wedding.

‘Then, a week ago, Archduke Quintus decided that the wedding must be brought forward by two weeks. The Archduke, I regret to say, has a superstitious belief in astrology, a trait that runs through his family all the way back to Rudolph the Valiant, who attributed his defeat of the Turks to the correct alignment of various stars in the January sky.’

Dr Watson grunted again, and somehow managed to convey through his grunt the full extent of his derision. ‘Pah! Don’t believe for a moment that the Turks retreated because the moon was in Capricorn, or anywhere else for that matter. I’ve no time for any of that nonsense. Although,’ he added slightly sheepishly, ‘I did once have an excellent win at Epsom backing a horse called Aquarius on the advice of a young lady who did.’

Before General Pellinsky could make any reply, Mr Holmes 33intervened. ‘The change of date, of course, required you to contact Count Rudolph. And I take it this proved impossible?’

‘Indeed!’ The old gentleman leant forward a little in his chair, and there was no mistaking the anguish in his words as he continued. ‘You see, sir, I have been wantonly deceived, and as a result, the fate of the Grand Duchy hangs by a thread.’

‘You were unable to locate him at any of the addresses on the itinerary?’

‘I was, Mr Holmes! For the very good reason that neither man had been within a hundred miles of the Alps.’ He gave a little snort, one that put me in mind of a wounded warhorse, then charged onwards. ‘It has taken a good deal of effort to piece together their movements after they ostensibly set out for the mountains, but it seems clear now that they travelled directly to London, and from there to Kemblings, the Count’s hunting lodge, where they deposited their bags.

‘The next morning the two of them rode out together, but only Christophers returned. It turns out that Captain Christophers is something of a favourite with the staff there, and he assured them that his friend was safe and well and off on an adventure of his own.’

Dr Watson allowed himself a low chuckle. ‘I daresay the young fellow’s out on a spree. Wouldn’t be the first bachelor to fancy living it up a bit before tying the knot, eh, Holmes?’

But his friend was not smiling. ‘Are we to take it, General, that even though their deception has been exposed, this man Christophers is still refusing to reveal his friend’s location?’

In reply, the general shook his head, and I was struck again by just how pale he looked. ‘It is a little more complicated than that, Mr Holmes. It would appear that Captain Christophers, 34and Captain Christophers alone, knows the whereabouts of his friend. But a fortnight ago Christophers went riding in the rain and came back to Kemblings shivering and soaked to the skin. For a few days he seemed to be recovering, but three days ago he was struck with a brain fever and is even now lying delirious in his bed.’

‘You mean he is unable to give you any information at all?’

The general hesitated. ‘I believe he is trying to tell us something. We have someone by his bedside day and night in case he becomes lucid even for a moment. But he drifts in and out of sleep, and when awake he mumbles and raves.’

The general met Mr Holmes’s eye. ‘Only four words have emerged clearly, sir, and he has repeated each of them more than once. Sometimes together but more often separately, so it is impossible to tell whether or not in his mind they are related.’

‘And those words are …?’

I held my breath, a small silver milk jug gripped in my hand as firmly as a drunkard grips his tankard.

‘Simply these. One location, repeated often: Piccadilly. One colour: white. One object: bridge. And perhaps the word he utters most frequently, a name: Herbert.’

CHAPTER THREE

The interview with General Pellinsky continued for another thirty minutes or more, but nothing the general added subsequently seemed to me to help a great deal in solving the puzzle of those four words. He was able to tell Mr Holmes very little about the Count’s acquaintances in Britain, other than the names of two London clubs that the missing bridegroom belonged to – Sharp’s and the Dampier Club, both of them fashionable establishments, popular with well-connected young gentlemen. But otherwise he could only repeat that his agents had interviewed local people, railway officials and everyone connected to the Rosenau Consulate, but no one had been able to provide any clue about the young man’s location.

‘And of course, Mr Holmes,’ the general repeated more than once, ‘all enquiries must be conducted with absolute discretion. No one must know that we are not currently aware of the young man’s whereabouts. The news would be succour to those who wish to tear Rosenau apart, and would, quite frankly, make us a laughing stock across Europe. Also, think of Princess Sophia’s reputation! The humiliating prospect of the whole world knowing her husband-to-be has vanished just days before he is supposed to marry her!’ 36

‘But you have informed the Princess?’ Mr Holmes asked pointedly. ‘And you have surely alerted the British authorities? You cannot hope to keep such a matter hidden from the public view for more than a day or two, and without the help of the various police forces, your chances of locating Count Rudolph in time for his wedding are, frankly, minuscule.’General Pellinsky looked distinctly embarrassed at this, and puffed out his cheeks not once but twice before replying. ‘I have not yet shared the news with Princess Sophia, Mr Holmes. My hope is that, with your assistance, Count Rudolph can be located promptly, and that no one but ourselves, my trusted agents and the Count’s own staff need ever know about this unfortunate interlude.’

Mr Holmes listened to this solemnly then began to pace the length of the hearth rug, pausing only to lean his pipe against a book about eighteenth-century stranglers, which had been left on one end of the mantelpiece. The general watched him anxiously, but no one spoke until Dr Watson could contain himself no longer.

‘Well, Holmes? What do you think? Can we help the general?’