Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

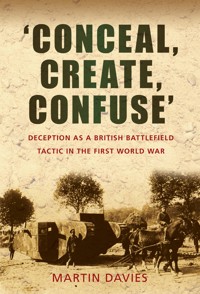

This is the story of the British Army's endeavours during the Great War to deceive the enemy and trick him into weakening his defences and redeploying his reserves. In this year-by-year account, Martin Davies shows how Sir John French and Sir Douglas Haig actively encouraged their Army commanders to employ trickery so that all attacks should come as a 'complete surprise' to the enemy. The methods of concealment of real military artefacts and the creation of dummy ones were ingenious enough but the real art lay in the development of geographically dispersed deception plans which disguised the real time and place of attack and forced the enemy to defend areas threatened by fake operations. Some of these plans, such as disguising mules as tanks and creating dummy airfields bordered on the farcical but were often amazingly effective. The driving force behind the deception plans was GHQ and the Army commanders, further dispelling the myth of 'Lions led by Donkeys'. Evidence shows that the British Army employed deception to advantage in all their theatres of operation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 453

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘CONCEAL, CREATE, CONFUSE’

‘CONCEAL, CREATE, CONFUSE’

DECEPTION AS A BRITISH BATTLEFIELD TACTIC IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR

MARTIN DAVIES

To Teresa, Rachael and Hannah

First published 2009

By Spellmount, an imprint of

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2016

All rights reserved

© Martin Davies, 2009

The right of Martin Davies to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978-0-7509-7908-5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Maps

Preface

Introduction

1

The No-Man’s-Land Conundrum

2

The Tools of the Trade

3

The Western Front 1914: Local Necessities

4

The Western Front 1915: Laying the Foundations

5

The Western Front 1916: The Reality of Deception

6

The Western Front 1917: Reaping the Rewards

7

The Western Front 1918: The Learning Curves Coincide

8

1915–1918: Other Theatres, Similar Stories

9

Deception, GHQ and the Army Commanders

10

The Effectiveness of Deception

End Notes

Bibliography

List of Maps

Map 1

Deception Plan at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, March 1915.

Map 2

Deception Plan at the Action at Hooge, August 1915.

Map 3

Deception Plan at the Battle of Loos, September 1915.

Map 4

German Deceptions to Conceal the Preparation for Verdun, February 1916.

Map 5

Deception Plan for the First Day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916.

Map 6

British Deception Plan for the Somme from the German Perspective, June–July 1916, p. 111.

Map 7

Deception Plan for the Third Battle of Ypres, July 1917.

Map 8

Deception Plan for the Battle of Cambrai, November 1917.

Map 9

Deception Plan for the Battle of Amiens, August 1918.

Map 10

British First Army Deception Plans for the Battles of the Scarpe, Drocourt-Quéant Line and Canal du Nord, 1918.

Map 11

The Final Hundred Days and the Breaking of the Hindenburg Line by the British First, Third and Fourth Armies, 1918.

Map 12

Deception Plan to Cover Landings at Gallipoli, April 1915.

Map 13

Deception Plan to Cover Landings at Gallipoli, August 1915.

Map 14

Deception Plan for the Third Battle of Gaza (Beersheba), October 1917.

Map 15

Deception Plan for the Battle of Megiddo, September 1918.

Preface

My interest in the use of deception arose from two disparate pieces of information. The first involved the periods of silence used by the British at Gallipoli in 1915 just prior to the evacuation. The artillery, machine gunners and riflemen were under orders not to fire or move around during those periods for the three weeks before the evacuation, but as the Turks send out patrols to investigate the unusual silence they were fired on. In this way, when the troops were evacuated and the trenches truly fell silent, the Turks were reluctant to investigate, which enabled the troops to embark in safety. The other piece of information came from F. Mitchell’s book on tank warfare. As a Tank Commander in the 1st Battalion, Tank Corps near the River Selle in 1918, he had witnessed the Royal Engineers constructing dummy tanks from canvas and wood, which were then strapped to the backs of mules. The two approaches, one brilliant in its simplicity, the other bordering on the ridiculous, were effective under the prevailing circumstances. From these examples it appeared that the British Army was comfortable with the use of deception but, with a few notable exceptions, the consensus has been that the British Army failed to exploit deception as a major weapon throughout the war. However, close examination has shown that this was not the case and beginning in 1914, the imagination of various officers and men was channelled into weakening enemy defences by creating illusions of attacks and concealing the real attacks so that the enemy commanders became confused as to the best deployment of their artillery, defenders and reinforcements.

As acknowledged in the photograph captions, some of the images are reproduced with the kind permission of the Royal Engineers Museum, Gillingham and I would like to thank Miss Charlotte Hughes for her assistance. For the photographs reproduced with the kind permission of the Tank Museum, Bovington I would like to thank Mr Stuart Wheeler for his assistance.

Martin Davies

Woolaston, Gloucestershire

Introduction

Hold out baits to entice the enemy. Sun Tzu

Military deception and ruses have formed a key part of offensive and defensive operations in conflicts throughout history, as military commanders sought to gain an advantage over their enemies by any means possible. As early as 500 BC Sun Tzu, the military strategist, stated that

All Warfare is based on deception … Hence, when able to attack, we must seem unable. When using our forces, we must seem inactive. When we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away. When far away, we must make him believe we are near. Hold out baits to entice the enemy. Feign disorder, and crush him.

Over 2,000 years later, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the military theorist, Carl von Clausewitz, concluded that ‘to take the enemy by surprise … is more or less basic to all operations for without it superiority at the decisive point is hardly conceivable.’

Although not necessarily institutionalised, battlefield deception has been used throughout history by various armies. Instances have ranged from the mythical Trojan horse at the siege of Troy to the successful feint retreat employed by William of Normandy at the Battle of Hastings (Senlac Hill) in 1066. The aim of these ruses was to gain even a small competitive advantage which in all great games could make the difference between victory and defeat.

Deception will never overwhelm enemy defences. However, deception can confuse those defences as to the time, the place and the troops involved in offensive operations so that defences are less prepared and reinforcements poorly deployed, both of which should increase the chances of a successful offensive operation. For these reasons, deception plans target the enemy’s decision-making processes at all command levels and strive to influence the actions of all military units.

Military decisions rest on discrete activities: the gathering and evaluation of intelligence, the assessment of possible actions and finally the issuing and carrying out of orders based on the final judgment. This simplified view of decision-making applies in both offensive and defensive operations. Although these activities have always existed, they were only formally recognised, explained and documented in the early 1950s, by Colonel John Boyd (1927–1997) of the United States Air Force. Boyd, who served first in the US Army Air Corps and then in the US Air Force from 1951–1975 as a fighter pilot, only ever described his theory on decision-making in a short essay and with slide presentations.1 Today his theory is universally accepted and is used as the basis for training programmes within the military, the police and corporate businesses.

During the Korean War (1950–53), Boyd observed that the technically inferior American F-86 Sabre Jets were more than a match for the North Korean MiG-15 aircraft with a kill ratio of at least ten-to-one. Boyd concluded that during aerial combat, decisions taken were the result of the pilots going through four distinct phases, which Boyd termed Observe (O), Orientate (O), Decide (D) and Act (A) – he coined the term OODA Loop for the whole process; later generations have also called them Boyd Cycles in recognition of his work. Boyd argued that the American pilots were successful because the bubble canopy of the Sabre Jets, compared with the semi-enclosed cockpit of the MiGs, enabled them to observe more, and more quickly, than their Communist counterparts. As a consequence, the OODA Loops of the Americans exhibited a shorter cycle time, or a higher ‘operational tempo’, which enabled the Americans to act on observations faster than the North Koreans and consequently achieve a higher ‘kill’ rate.

From the specialised environment of aerial combat, it was quickly realised that all military decisions, and probably all decisions taken in life, whether taken consciously or subconsciously, had to follow the same four phases. In military terms, if intelligence could be gathered, processed and acted upon faster than the enemy, an immediate advantage would ensue. Further, as these decision-making processes existed at every level throughout an army, from the Commander-in-Chief down to the private soldier, it was important that enhanced operational tempo was present throughout. This need was one of the driving factors behind the development and equipping of the ‘fighting platoons’ in 1917 and was used to great effect by the British Army in 1918 to maintain pressure on the German units during the retreat throughout the Final Hundred Days.

Although General Headquarters (GHQ) and the Army Commanders during the First World War would not have recognised the term ‘OODA Loop’ and the individual phases, they would have recognised the decision cycle that this represented. Intelligence would have been gathered (Observe phase) and evaluated (Orientate phase), decisions would have been made regarding the intelligence (Decide phase) and finally orders would have been issued and implemented (Act phase). These decision-making processes within any army are the DNA of its chain of command and are the key elements, along with the actual offensive actions, in the successful execution of military operations. These are also the elements that deception plans target. To disrupt these processes, belligerents have consistently employed two principal approaches.

The first approach is to shorten the time taken from receipt of intelligence to the issue of orders in response. The term ‘operational tempo’ has been latterly applied to this approach. The speeding up of the decision-making processes results in the enemy making decisions based on ‘old’ intelligence as the situation has changed from that upon which his information was originally based. Throughout history, the great commanders have always recognised a developing situation on the battlefield (Observe) and immediately acted on it (Orientate, Decide, Act). This was relatively straightforward where commanders could be present on the battlefield and where chains of command were comparatively short. However, increasing operational tempo becomes more difficult as army chains of command become longer and the nature of the interactions more complex. Intelligence has to be gathered and assessed and decisions have to be made within the command chain and then communicated and implemented often by a variety of units, each with their own unique perspective on the battlefield. In the British Army, after December 1914, there was a hierarchy of command from Army down through corps, division, brigade, battalion, company, section and platoon. At each level within the chain of command, there were separate OODA Loops. Each of these Loops derived its intelligence from information (orders) disseminated to it by the command structure above it in the chain, from battlefield reports emanating from the command structures below it and locally from its own observations regarding the situation. For success, the OODA Loops had to be synchronised, which was difficult as the margin for disruption was great. As the war progressed, the British Army introduced a command structure that to a certain extent de-synchronised the OODA Loops, with the introduction of a devolved command structure on the battlefield, especially at brigade level, and with the introduction of the ‘fighting platoons’, which had the ability to take battlefield decisions based on local conditions. There was of course a similar vulnerability in the German Army’s chain of command and this was something that the second approach to disrupting the decision-making processes tried to exploit.

The second approach, which is arguably easier to implement and achieve, was to create false intelligence and feed it into the enemy’s OODA Loops. The deception was specifically targeted at the evaluation, or Orientate, phase, which would determine subsequent military actions. Although deception at first sight seemed to be aimed specifically at the Observe phase, ‘letting-them-see-what-you-want-them-to-see’, it was in reality targeting, in a more subtle manner, the Orientate evaluation phase so that the enemy would interpret the false intelligence ‘correctly’, make the ‘desired’ decision and take the ‘desired’ action. Addressing only one of the phases would weaken the effectiveness of the deception and therefore it has to be designed to influence both the Observe and Orientate phases so that subsequent enemy actions are appropriate for the ‘deception intelligence’ but inappropriate for the actual situation. Boyd in 1987 recognised that the Orientate phase of the OODA Loop is the crucial element as it dictated the end result of the decision cycle. A plethora of false intelligence could be generated, each element of which in isolation would be credible, but when evaluated together, inconsistencies would immediately discredit all the intelligence at the Orientate phase. To address both the Observe and Orientate phases in this manner means that deception plans have to be complex affairs and not simple activities conducted in isolation by various units throughout the army. This approach does assume that the enemy Orientate phase is functioning correctly and there were examples on both sides throughout the war when the Observe phase gathered intelligence which was incorrectly evaluated during the Orientate phase and resulted in serious casualties and loss of territory.

The fact that deception must target multiple phases of an OODA Loop meant that deception intelligence had to be plausible, consistent and predictable, i.e. ‘logical’, for the enemy’s own assessment. The complexity of deception lies in the fact that the plans must deceive the enemy commanders as well as the enemy’s intelligence service. The plan should be so convincing that friendly soldiers, who are not privy to the deception, must believe it and be seen to be reacting to it rather than to the actual situation. On the Western Front where raids across No-Man’s-Land were commonly undertaken as a means of gathering intelligence from captured soldiers, British troops who believed the deception often told the ‘truth’, which gave increased credibility to the deception activities.

Military historians have frequently been dismissive of the British Army’s approach to deception during the First World War. It has often simplistically associated deception with concealment (camouflage) and the deployment of dummy artefacts (canvas tanks, dummy heads). But this is a naive approach which was not systematically adopted by the British Army during the war, as this would only have targeted the Observe phase at a local level. There is clearly evidence for the deployment of canvas tanks and dummy heads and the extensive use of camouflage, but these were just indications of something happening on a much grander scale. This was summed up in the British Army’s military pamphlet SS206, published in 1918, which insightfully stated, ‘deception, not concealment, is the object of camouflage’. Modern military planners base their deception plans on ten maxims or principles which were identified during a study by the United States Army in 1988.2 These principles highlighted the complexity of deception plans far beyond the simple deployment of dummy tanks and will be discussed in detail in Chapter 10. From September 1914 until August 1918, the static nature of the warfare on the Western Front and the close proximity of the enemy required something more sophisticated to mislead the Germans and the deployment of their critical reserves necessary for the all important counterattack. Plausibility, consistency and predictability require complex strategic and tactical planning as well as a disciplined implementation.

The characteristic of plausibility was satisfied if the plan, and consequently the intelligence generated by it for the consumption of the enemy, was rational. During the build-up to the Fourth Army’s attack on the Somme on 1 July 1916, the Third Army also built up men and supplies and fired bombardments in their sector. General Erich von Falkenhayn, the German commander, considered the Third Army activity to be reasonable – plausible – as he believed that an attack on the British Third Army front in July 1916 was a rational act. As a consequence, Germans reserves were held behind the Third Army sector on 1 July as Falkenhayn at first believed that the Fourth Army operation was only a feint designed to draw those reserves away. Interestingly, his army commanders, General von Below and Crown Prince Rupprecht, did not agree with his assessment.

The consistency element of the deception plan demanded that all units that were involved in the deception must be observed to be reacting to it, rather than the real plan, and in a manner that was characteristic of the British Army. Before the war, each of the major protagonists had acted as official observers at each other’s annual manoeuvres. As a consequence, through this and other mechanisms, they knew the behavioural patterns of each other’s armies. The consistency of deception planning can again be illustrated in the build-up to the attack on 1 July 1916 where the activities of the Fourth and Third Armies were indistinguishable from each other. There was little difference in the activities of the Third and Fourth Armies in June 1916 to indicate that either or both of the armies did not mean to attack. It is essential that the deception plan and the real plan are consistent with each other. As such, a deception plan must be almost as secure as the real plan and the enemy must be made to work hard to gather the intelligence regarding it. It is vital that there are no discernible differences between real and false intelligence and all intelligence must be seen to have been gathered either as a lapse in security or as a result of clever intervention or significant effort on the part of the enemy. At no point should any obvious facilitation be made to ‘feed’ the enemy with deception plan intelligence. Hence the security surrounding both the real and false intelligence must be equally secure or, more dangerously, equally lax. If the latter approach was employed, which could be the case for instance when it was impossible to hide the preparations for a real attack, the enemy OODA Loops were presented with a volume of intelligence, both real and false, that swamped the Orientate phase. This stalled the loop whilst the real and false intelligence was evaluated. The aim was to confuse the enemy so that when the real offensive began, together with the supporting demonstrations, their indecisiveness would be of sufficient duration to afford a tactical advantage. The Allied landings at Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli Peninsula in August 1915 demonstrated this admirably. The Allies were only opposed by three Turkish battalions while further north at Bulair, three Turkish divisions were held in position by a feint attack by the Royal Navy. After the feint attack was exposed for what it was, the 7th and 12th (Turkish) Divisions were transferred south to bolster the defences around Suvla Bay. This deception followed Magruder’s Principle, a key element of all successful deception plans, which will be discussed later.3 The fact that the Allies failed to seize the initiative on the ground to overwhelm the initial paltry defences and gain the high ground was a basic failure of offensive operations and not of the deception plan.

The final characteristic, predictability, means that the deception plan must create a situation that the enemy can relate to, one in which they might have adopted the same tactical approach for real, if the roles had been reversed. This was one of the key factors in the success of General Sir Edmund Allenby’s deception at the Third Battle of Gaza (October 1917). Part of the plan played on the belief of General Kress von Kressenstein, the German officer in command of the Turkish forces, that the attack on Beersheba could only be a feint, as a full-scale attack did not align with his preconceived tactical assessment of the situation. At Gallipoli in both April and August 1915 the deception plans initiated against Bulair and the Asiatic coast targeted the troop deployments of Field Marshal Otto Liman von Sanders, the Turkish commander. Von Sanders considered Bulair and the Asiatic coast as strategic Allied targets and as a consequence deployed significant numbers of troops to protect these areas. The Allies targeted them with their deception plans, having no intention of attacking them. Deception plans must be placed within the same strategic and tactical context as the real plans. Both of these examples exhibit plausibility and obey Magruder’s Principle, which exploits the existing beliefs of the enemy commanders. Magruder’s Principle will be referred to on numerous occasions, as it was one of the elements of deception planning that the British got right from the beginning of the campaign.

It is by using the qualities of plausibility, consistency and predictability as criteria that the enemy’s Orientate phase is targeted. Creativity and discipline are prerequisites. However, the deception still relies on the ‘correct’ interpretation of the intelligence by the enemy and this becomes the ‘uncontrollable’ element in all deception plans. When deception plans are executed, there are a number of potential outcomes, which range from the plan being accepted wholesale by the enemy, to their penetrating the plan and using it to their advantage. Consequently, it is important that when executing a deception plan, intelligence is gathered continually through observations and prisoner information, and the situation is continually monitored to ensure that the enemy has indeed been duped by the deception; a failure to gather real intelligence in this respect could result in significant casualties.

For real success, an army should attempt to disrupt the enemy’s decision-making processes through the operational tempo and deception, as deception planning becomes especially effective with an enhanced operational tempo. The time available for intelligence evaluation by the enemy is decreased which diminishes the likelihood of detection. The British Army strove to achieve this throughout the war but as increased operational tempo involved a multitude of disciplines including firepower, offensive tactics, logistics and transportation, this was arguably only fully realised in the last four months of the conflict.

There have been a number of modern publications on the subject of deception in warfare but in the main these have concentrated on events from the Second World War until the present day. Those few considering the First World War have tended to concentrate on the ‘headline’ events where deception was famously used – at Gallipoli in December 1915, at Gaza in October 1917 (the ‘Haversack Ruse’) and at Amiens in August 1918. As David French pointed out in 1994 regarding the First World War:

Little has been published about the way in which the British used deception as a way of masking their intentions from their enemies … perhaps because it runs … counter to the notion that the British Army was led by ‘donkeys’ who were too lacking in subtlety to devise such measures.4

What is apparent from a review of the information sources, including the Official Histories, is that the British Army systematically used deception to support its military operations throughout the war. It was introduced as early as December 1914, five months after the start of the war, with the first truly integrated deception plan implemented at Neuve Chapelle in March 1915. A failure to use deception to support offensive operations would have indicated that the British Army was unimaginative and naive in its approach to military operations. Further, if deception was practised but was not analysed for its effectiveness, then the army command and control structures would not be following a learning curve. This would tend to contradict the arguments of those historians who have identified the existence of distinct learning curves for various facets of the British Army during the war. It would support the notion that the war really did see lions being led by donkeys! On the contrary, there is evidence that the use of deception in support of operations originated from GHQ and the various Army Headquarters, rather the lower level units, as deception was seen as a key element in successful offensives. From Neuve Chapelle (March 1915) through to Cambrai (November 1917) and Amiens (August 1918), the Army Commander’s instructions at the start of the offensive planning process were adamant that attacks must come as a complete ‘surprise’ to the enemy! It is important to note that the British Army rarely used the word ‘deception’ or its derivatives but employed von Clausewitz’s favoured term, ‘surprise’.

The Lessons of Three Conflicts, pre-1914

At the British Army’s military training establishments at Sandhurst, Camberley and Woolwich, the young officers were routinely given case studies to analyse and appreciate based on past conflicts including the American Civil War (1861–1865), the Second Boer War (1899–1902) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). British military observers were present throughout most of the latter conflict and subsequently published their findings. In September 1909, Lord Kitchener was feted on a tour of the battlefields in Manchuria. All three conflicts provided striking examples of the military advantages that could be gained through the use of deception and the disadvantages of its neglect. For the Confederate Army at Corinth (1862) and the British at Mafeking (1899-1900), it is difficult to envisage a successful outcome to the operations without the use of deception. Hence at the start of the First World War, the British Commanders should have been aware of the potential of deception and well acquainted with previous examples, especially as a significant number of the brigade commanders had served in the Boer War.

The American Civil War, the first of the modern conflicts characterised by man-power, technology and finance, lasted from 12 April 1861 until 9 April 1865. 3,277,000 men were mobilised of whom 29.6 per cent became casualties. Whilst the United States Army outnumbered the Confederate States Army by approximately two-to-one, the Confederacy inflicted almost twice the number of battlefield casualties on the Union in a war of attrition that the CSA could never win. In general, the Confederacy made good use of deception to redress deficiencies in materials and manpower, something that would prove to be directly applicable to the British Army in the First World War.

In September 1861, six months after the start of the war, the Confederate guns that had been trained menacingly on Washington were overrun and found to be no more than painted logs to which old wagon wheels had been fixed. The guns, subsequently termed ‘Quaker Guns’ set the pattern for deception which the South perpetrated to make up for their lack of men and materials. Interestingly, the ruses carried out by the Confederacy had relevance not only for the First World War but also for subsequent conflicts. The term ‘Quaker Gun’ would have been recognised by First World War officers.

In 1862, Major-General George B. McClellan (known as ‘Little Mac’), Commander-in-Chief of the Union forces on the York-James Peninsula, was in command of 120,000 men but was unaware that he faced a much smaller Confederate force of 8,000 troops. The latter was commanded by John Bankhead Magruder, a consummate showman whose deception inventiveness was limitless. McClellan believed that the strength of the Confederate force was greater than it was, but in reality Magruder defended a thirteen-mile front with too few men and far too few guns. Magruder played upon McClellan’s belief. The initial deception was simple enough in that Magruder mixed real guns with Quaker Guns; but to confuse enemy intelligence he elaborated. He continuously moved around his units, conveying the impression that his force was greater than it was, he played loud band music at night indicative of a relaxed garrison while he himself rode around conspicuously with a colourful entourage sending out the clear message that he and his troops were everywhere. To finish off the deception, Magruder had a single infantry battalion march continuously along a heavily wooded road to the side of which was a single gap in the trees, clearly visible to the Union troops. The Confederate soldiers marched in a circle all day long conveying the impression that they were an extremely large force. This latter ruse was utilised to great effect fifty years later at ‘C’ beach at Lala Baba on the Gallipoli peninsula in December 1915; and by General Sir Edmund Allenby, Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, at Gaza in October 1917 and again at Megiddo in September 1918, which played a significant role in the defeat of the Turks. A variation on this ruse was also used on the Western Front at Arras in November 1917 using six tanks in support of the preparations for the tank battle at Cambrai, thirty miles south east. By ‘re-cycling’ the tanks, the British led the Germans to believe that a large concentration of tanks was present in the Arras area preparing for a major offensive. The Germans shelled them, failing to spot the real build-up of over 400 tanks in front of Cambrai.

In a review of deception since 1914 published by the United States Army Military Intelligence in 1988, Magruder was recognised as one of the innovators of deception and as a result one of the ten principles of a good deception plan has been attributed to him. Magruder’s Principle states that if the enemy has a pre-existing belief – in the original scenario McClellan thought that Magruder’s force was greater than it was – then this should be exploited by the deception plan rather than trying to change that belief.

A further useful example from the American Civil War that would find an echo in the First World War was the retreat of the Confederate Army in May 1862. Just like the British Army at Gallipoli in 1915, the CSA needed to retire under direct enemy observation with the minimum casualties. Both the Confederate Army and the British Army extracted themselves using similar techniques, although the Confederacy used trains and the British used ships.

Major-General Pierre G.T. Beauregard had to evacuate his wounded troops first and then his fighting troops from the town of Corinth in the face of a strong Union force. Corinth had a railhead and Beauregard arranged for trains as the means of extricating his troops. As the empty trains arrived, Beauregard had the band play and a regiment of troops cheer as if reinforcements were arriving. However, when the ‘empty’ trains left, initially full of wounded, all was silent. In this way not only did Beauregard safely evacuate the wounded but he also conveyed the impression that his garrison was growing significantly, making a Union attack less likely. Beauregard elaborated upon this by sending ‘deserters’ through to the Union lines to spread disinformation and confirm the build-up of troops within Corinth. A variation of this ruse was perpetrated at Anzac and Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli peninsula in December (see chapter 8).

Beauregard’s real challenge came when it was time to evacuate his front line troops. The troops left the trenches silently at night leaving behind drummer boys who kept the fires going and sounded reveille in the morning. They were supported by the band which moved around. An empty train went continuously back and forth during the day and was always greeted enthusiastically on arrival. The British at Gallipoli used a variation of this.

After the Confederate Army had left, the Union soldiers, alerted by the silence, eventually moved forward, only to find Quaker Guns manned by dummy straw soldiers. At Gallipoli, the problem of ‘silence’ in the trenches was overcome by ‘conditioning’ the Turkish troops in the preceding weeks to accept the idea that silent trenches could still be full of troops.

In the last major conflict involving the British Army prior to the First World War, the Second South African War (Boer War) (October 1899-May 1902), deception was routinely practised. Due to the mobile nature of the guerrilla warfare in the latter stages, deception developed to meet needs at a local level and hence was tactical rather than strategic.

At the siege of Mafeking, Colonel Robert Baden-Powell and his small force were surrounded and outnumbered ten-to-one by over 8,000 Boer troops lead by Commandant-General Piet Cronje who besieged them from 16 October 1899 until 17 May 1900. For 217 days Mafeking was cut off from the outside world and at the mercy of the Boers. Interestingly, one of the last pieces of mail to leave Mafeking, before the siege was laid, was the final manuscript of Baden-Powell’s magnum opus, Aids to Scouting.

Baden-Powell decided that deception and trickery could be the key to his survival. He developed an integrated deception plan whilst issuing instructions to his garrison to deceive the enemy at every possible turn. Baden-Powell’s plan was aimed specifically at conveying two messages to the Boers, that the British garrison was bigger than it really was and that the British defences were more formidable than they really were.

At the outset, a series of fake outpost forts were set up around a five-and-a-half mile perimeter, a distance too large for a small garrison to man effectively thus conveying the impression that the British were a greater force than Boer intelligence had led them to believe. This also enforced the Boers’ belief that the British knew what they were doing. Baden-Powell created one of the forts, a mile-and-a-half away, from a large mound of earth, buildings and trenches. The fort was adorned with two large flag poles to give the impression that this was Baden-Powell’s headquarters; this site was extensively shelled by the Boer artillery.5 The false headquarters created the impression that Baden-Powell was in command of the fort line and not managing operations from back in Mafeking itself. This ruse is similar to that which Sir Douglas Haig would perpetrate at Neuve Chapelle in March 1915 and Sir Henry Rawlinson on the Somme in 1916 to mislead the Germans with respect to the sectors to be attacked.

Baden-Powell also made full use of the numerous Boer spies within Mafeking itself by planting dummy minefields, laid in view of the Boers and their spies. To create these minefields, natives carried boxes (filled with sand) around the town to the sites of the minefields with strict instructions not to drop them! For authenticity, one of the minefields was tested and after all the inhabitants had been ordered indoors, ‘for their own safety’, a dynamite charge was set off.

Further, after Baden-Powell had observed the Boers high stepping over their barbed wire defences, he constructed fake barbed wire (string tied to wooden pickets) and ordered the British troops to simulate avoiding non-existent barbed wire by exaggeratedly stepping over it when moving between trenches. Both the ‘barbed wire’ and the ‘minefield’ presented formidable obstacles to any attackers. The type of deception was the forerunner of the dummy trenches used throughout the First World War and which Haig instigated as early as 29 October 1914 at Gheluvelt, as part of the First Battle of Ypres (10 October–22 November 1914).

Recognising that the town was vulnerable to attack by night, one of Baden-Powell’s engineers created a ‘searchlight’ made from an acetylene torch and a biscuit tin mounted on a pole. This was shone from one of the forts towards the Boers before moving on to the next fort. The Boers assumed that any night attack would have to be made in the full glare of searchlights which would make any attack hazardous. The use of searchlights as a means of concealing the truth was used to great effect during the Dardanelles Campaign both during the attack at Chunuk Bair in August 1915 and during the evacuation from Anzac Cove in December 1915.

Baden-Powell’s engineers next developed a megaphone from a biscuit tin that could convey messages and orders up to 500 yards. Baden-Powell would issue orders to fix bayonets and prepare for attack which would result in a hail of retaliatory rifle fire from the Boers, who were subsequently targeted by British snipers as they disclosed their positions! This tactic was a direct ancestor of the famous ‘Chinese Attacks’ used on hundreds of occasions throughout the First World War by the British Army.

Finally, to fool the Boers into thinking he had a much larger force, Baden-Powell resorted to the tried and trusted trickery that had served the Confederacy so well forty years earlier and would serve the British Army equally well fifteen years later. He moved his men and the few available cannons around from place to place and with the aid of dummy soldiers, simulated a large force.

The overall impression worked well as the Boers never tried to invade the town although they launched an eventually abortive attack on 12 May. This attack was broken up by Major (later General Sir) Alexander Godley, the officer who would be responsible for a simple but effective ruse at Gallipoli in 1915. In the main the Boers were content to shell Mafeking from a distance, for fear of the British Army’s massive armaments. Given the prominence that the Siege of Mafeking held in the British consciousness, it cannot have gone unnoticed within the Army that the successful outcome was due almost entirely to bluff and deception. Both the future commanders-in-chief in the First World War, Field Marshal Sir John French, as a cavalry commander, and Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, as one of his staff officers, played prominent roles in the Boer War. This wealth of Boer War experience extended down the chain of command. Analysis of the ‘Donkey Archive’ at the Centre for First World War Studies at the University of Birmingham,6 shows that in 1914, 62 per cent of the brigade commanders had seen active service in South Africa during the Boer War with a further 15 per cent having seen active service in other theatres.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) existed despite evidence from the Russo-Japanese war in Manchuria (1904–05) that industrial nations would wage ’industrial’ wars and that expeditionary forces were inappropriate for these ‘heavyweight’ conflicts. The Manchurian War in many respects represented a blueprint for the First World War as trench warfare had developed, with the key defences of barbed wire belts and machine guns with interlocking fields of fire. The development of rifles and ammunition after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) increased their effectiveness with the introduction of new rifle magazines that raised the rate of fire, smokeless powder cartridges and increased ranges. This in turn forced the artillery to dig in and adopt bullet shields or deploy farther back so that they could not be targeted by the enemy infantry and to introduce new methods of indirect firing where the target could not be directly seen. Through indirect firing at the Battle of Sha-ho (11–17 October 1904), the Japanese artillery, firing from reverse slope positions, silenced the Russian artillery and machine guns. The Japanese had employed a system of artillery observers who did have line-of-sight and were in communication with their guns.

One of the other lessons that emerged from this conflict was the judicious use of deception. In general and where possible, the Japanese employed deception, while the Russians more or less expressed contempt for its use. Geoffrey Jukes has speculated that without the skilful use of cover, camouflage and deception, the enormous Japanese casualties incurred in attack would have been even higher.7

At the Battle of Yalu (25 April–2 May 1904), the Russian Army and the Japanese First Army faced each other on the opposite banks of the Yalu river. The Japanese carried out their preparations under the cover of darkness or through the careful use of natural features to hide their intentions from the Russians. Disguised as local fishermen they were able to determine the locations of the majority of the Russian troops, guns and positions. The Russians, on the other hand, made no attempt to conceal any of their preparations. Furthermore, the Japanese found that the water level in the river was relatively low but then implemented a deception plan to conceal this fact and to force the Russians into revealing those remaining artillery positions that the Japanese had not already detected. The Japanese, in full view of the Russians, commenced the construction of a ‘decoy’ bridge across the Yalu’s main channel. The Russians expended a lot of ammunition and revealed all their artillery positions trying to destroy the bridge. This plan followed one of the principles of all good deception plans, Magruder’s Principle, in that had the situation been reversed, this is where the Russians would also have built a bridge to get their army across the river. Meanwhile, the Japanese, hidden from Russian observers, used the premises of an abandoned timber company to build nine short portable bridges which were subsequently rushed into position across the narrower channels immediately prior to the attack.8 At Tel el Fara in Palestine 1917, the British Army constructed a fake bridge as a decoy target for Turkish aircraft to divert their attention from the real railway bridge, which was built without interference.9 A similar ruse was also perpetrated at Le Hamel on the Western Front in July 1918.

This pattern was reproduced throughout the Russo-Japanese war and was noted by the foreign observers. The Japanese concealed their artillery, the Russians did not. The negligence of the Russians was inexcusable; in dry weather, every time their guns fired, great tell-tale clouds of dust were thrown up, something which could have easily been remedied by dampening the soil around the gun positions with water from nearby rivers.

On rare occasions, the Russians did employ deception and fooled the Japanese because the apparent Russian moves fitted in with Japanese expectations. At the Battle of Sha-ho, believing that the Japanese would expect an attack on the flat plain, General Aleksey Kuropatkin, Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Armies, in line with Magruder’s Principle, advanced on to the plains with bands and banners. This ostentatious display was believed by the Japanese, given the Russian’s previous behaviour in the war and their own pre-conceptions of the situation.

Kuropatkin surprised the Japanese by launching an attack on his left flank through the mountains. With his expectations set, Field Marshal Oyama, the Japanese commander, refused to believe that the mountain attack was anything more than a feint and that the main attack would still come across the plain.

After the war, British officers studied the conflict and concluded that there were lessons to be learnt, particularly about concealment, the use of camouflage and the cover of darkness to prepare for an offensive. Barrett published an article in which he described how once the Russians guns had detected a Japanese battery and they came under fire, the latter often fell silent and moved to a new location, leaving behind remnants to simulate a burnt-out position.10 This ruse was perpetrated on the British by the German artillery at the Battle of Loos (September 1915) while the British used a variant to target German batteries at Amiens in August 1918.

Modern Armies and Deception

Despite evidence of the advantages of deception, it does not necessarily automatically feature in the planning of modern military operations. As late as 1983, military personnel in the United States Army were advocating that deception should be incorporated into every tactical organisation and should be reflected in unit training.11 So there was no guarantee that the British Army during the First World War would automatically employ it. Armies do not necessarily learn the lessons of history as they can often seem irrelevant in the face of significant technological advances. The United States Army conducted a series of studies of the use of deception to determine whether it was relevant to modern operations. One such study, made in 1988, examined engagements since 1914, although the overwhelming majority of examples used to support the conclusions within the document came from the Second World War, with no actual examples quoted pertaining to the First World War.

Nevertheless, the United States Army document is effective as a field guide in the use of battlefield deception. The study concluded that deception has made a significant contribution to military operations and deception enhanced the instances where surprise was achieved. The authors estimated that since 1914, warning of an imminent attack was transmitted to the enemy in about 78 per cent of all encounters but if this was accompanied by deception the warning was ignored and surprise was achieved. With the close proximity of the Germans across No-Man’s-Land on the Western Front, an imminent attack would have probably been detected in almost 100 per cent of instances! Even those times when the German High Command thought that an attack was not likely, for example at Amiens in August 1918, the troops at the local level had detected the tell-tale signs. In this case the German commanders chose to ignore the evidence because the intelligence generated by the British deception plan indicated that the attack would be 100 miles farther north. It is the abundant mixture of real and false intelligence that can temporarily paralyse the enemy’s OODA Loops so that countermeasures against detected attacks are not necessarily implemented in a timely manner.

The ten principles or maxims to a degree were based on the principles laid down by Sun Tzu, but were subsequently reinforced from a study of a number of conflicts including the First World War. Through deception the enemy had to be distracted, his intelligence collection and analytical capabilities had to be overloaded, illusions of strength where there was weakness and weakness where there was strength, the enemy had to be conditioned to patterns of behaviour and above all, the enemy expectations had to be confused with regard to Size, Activity, Location, Unit, Time and Equipment, known as SALUTE. Without knowing it, the British Army followed these maxims in its deception planning, as will be evident from the studies of particular battles in the following chapters.

The British Army pre-1914

In the fifty years prior to the First World War, France, Germany, Russia and the United States had fought continental-style industrial wars and France and Germany maintained a significant military presence through the use of conscription. In contrast, during the same period Britain had been engaged in colonial wars including the British-Zulu War (1879), the War in the Sudan (1881–1899) and the Second Boer War (1899–1902). These conflicts distracted command from the realities of British engagement in a continental war despite the study of the industrial conflicts at Sandhurst and Woolwich. Even as late as September 1914, military discussions mulled over flanking manoeuvres and the dominant role of infantry compared with artillery. Although machine guns were acknowledged as weapons capable of volume-fire, as a factor they were considered of no real significance, even though the British cavalry had adopted them in 1908 as a key element within its offensive arsenal. Further, despite the evidence from the Russo-Japanese War, at which the British were observers, the development of artillery tactics and trench warfare were not seriously considered.12 This blindness can be seen in the development of the British Expeditionary Force itself, which was developed as a rapidly deployable force designed for short, frantic engagements. Major-General J.M. Grierson had identified five strategic situations in which the British Army could become embroiled and it was on the basis of this analysis that Richard Burdon Haldane (later Viscount Haldane) proposed a set of reforms which resulted in a special army order issued by the War Office on 12 January 1907 for the reorganisation of the Regular Army, which included the creation of the BEF. The five strategic situations were a war with Russia in defence of India, a war against the United States in defence of Canada, a war against France, a war with France as an ally against Germany and finally a Third Boer War. In four of the five scenarios, the BEF would have had to engage a continental-style industrial army. This was likely to lead to a longer term engagement and not the short, decisive action that the BEF envisaged. In 1906, Haldane had dismissed the idea of a mass army as untenable, pointing out that Britain had a greater expeditionary force that either France or Germany.13 However, Haldane did propose that a Territorial Force of over one million men should be created. As a consequence, on the declaration of war on 4 August 1914, the British Army was ill-prepared for the industrial scale of the conflict it was about to enter.

Nevertheless, within seven months after the declaration of war, the British Army, having recognised the long-term and ‘industrial’ nature of the war, was actively engaged in offensive operations, against entrenched positions, which were supported by the use of deception plans that already followed the aims and maxims subsequently identified over 70 years later. This use of deception, particularly on the Western Front, has not been recognised and a number of publications have actually pointed up the Army’s lack of deception planning. For instance, Michael Handel stated that the British Army almost ignored deception because the British were confident that straightforward military might would be sufficient to overwhelm the enemy.14 Handel concluded that any deception plans were solely as a result of their implementation at a local level by local commanders and were extremely rare at a strategic level. This view was supported by Roy Godson and James Wirtz who recognised that deception was attempted but due to the close proximity of the enemy across No-Man’s-Land, it was difficult to conceal the concentrated build-up of men, artillery and materials.15 This problem was compounded by the fact that the advances in camouflage that might confuse aerial reconnaissance would not necessarily confound spies on the ground. This view is sustained by Michael Occleshaw in his book on military intelligence, which cited the ‘Haversack Ruse’ example at Gaza/Beersheba (October 1917) as a use of deception that could never be repeated on the Western Front. He concluded that the primary reason for this was that the armies were separated by No-Man’s-Land, and as a result deception on the Western Front was not a significant factor.

The above points are valid; but all of these issues were recognised by the BEF and its commanders, probably as early as December 1914. Based on references within the British, Canadian and Australian Official Histories, there is evidence that in the realm of deception, plans were being laid after seventeen weeks and the Western Front was as active as any of the other fronts in this regard and probably led the way. Almost immediately, as the opposing trench lines formed, the British Army on the Western Front recognised the limitations imposed by No-Man’s-Land and the potential for behind-the-lines spies. Straightaway the problem of how Allied offensive operations could be conducted without the Germans immediately being privy to all the preparatory activity and consequently making suitable defensive preparations that would counter any operation – whilst inflicting serious casualties – was recognised. The conundrum was not resolved in 1914 as the British Army had its attention focussed on other more pressing matters. By December 1914 however, there were signs that Sir John French had started to develop a potential solution to the problem. By March 1915 at Neuve Chapelle, the British were using dummy and camouflaged military artefacts, and providing a torrent of false intelligence that simply overwhelmed the enemy’s decision-making processes. The flow of false intelligence was often achieved simply by GHQ instructing units across wide sections of the front to start preparations for an offensive. Even fake preparations would involve camouflage to conceal them from the Germans, in the knowledge that spies would detect at least some of the activities and report back. The camouflage used for fake preparations was necessary not only to conceal the false nature of the preparations but also because the German artillery would target them and casualties had to be kept to a minimum! The deception plans at Neuve Chapelle were already complex in nature. As General Sir Douglas Haig prepared a deception plan to support the offensive of the First Army against Neuve Chapelle, Field Marshal Sir John French instructed the Second Army, commanded by General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, to simulate preparations for an attack against the Ypres Salient and Lille. The Germans were apparently faced with imminent offensives on both the First and Second Army fronts, so where should they deploy their reserves? Unbeknown to the Germans, the British had neither the manpower nor the artillery to simultaneously conduct offensives on both fronts. Despite the successful deception, in 1915 offensive operations had yet to mature into an approach that could overrun complex trench lines and resist the predictable counterattacks.

By the end of 1915 and the Battle of Loos, the British approach to deception planning was relatively mature although it would be refined through experience and as new technological advances, particularly tanks, became significant factors. Charters and Tugnell thought that the First World War was something of a watershed for the British Army as it used deception on the battlefield to support military operations.16

The use of deception plans throughout the First World War can be attributed to the approach of both Sir John French and Sir Douglas Haig at the start of 1915. The solution which resolved the No-Man’s-Land conundrum consisted of the three basic elements of Conceal, Create and Confuse (deception’s 3C). The Conceal element followed the lead of the French Army who had begun their work on camouflage by setting up a school in September 1914. Throughout 1915 the British Army relied on French expertise and manpower to develop camouflage techniques. The British themselves introduced the all-important second element of Create by the time of the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. It was evident that camouflage alone was not the answer as it could be easily penetrated. Therefore the British Army introduced the second element to create a wealth of false intelligence. This intelligence coupled with that which the Germans gathered by penetrating camouflaged artefacts gave them a problem – the separation of the real from the false. This it was hoped would ‘paralyse’ the decision-making processes long enough to Confuse them when the attack came. It was anticipated that the indecision, if only for a brief period, would be sufficient to enable the attackers to cross No-Man’s-Land and capture the first line of trenches. Subsequent trench lines would not benefit from this type of deception although at Bazentin Ridge on 14 July 1916, British pilots transmitted fake wireless messages which indicated that the second line had been captured, in the hope the Germans would not reinforce this line and would fall back to their third line. In the event, the Germans failed to pick up the messages and subsequent reinforcements forced the British to retire.17