Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

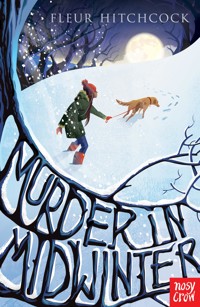

Murder and mayhem disrupt a family Christmas by the sea - a perfect thriller to keep you gripped this festive season! George and his family are celebrating Christmas by the sea. But when a body washes up on the beach, George can't stop thinking about the strange lights he saw on the cliff top... Neither can his cousin, Isla. Together, they follow the clues, and as they draw nearer to the truth, they step further into danger. On land, or at sea, someone is desperate to stop them, whatever it takes. And that someone may be closer to home than they realise...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 227

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

iii

For Lal, my big sister, who told me about the golden ammonites, and who may take issue with the geography.

iv

Prologue

The pale painted boards of the deckchair hut shone through the scribbles of snow falling on the shore. Something else showed through too, something grey, drifting in and out in the surf.

Only the sea crows saw it.

The Christmas trees leaning from the buildings became brighter, the amusement arcade music became louder and a single dog walker stopped and peered towards the unfamiliar object caught in the tide.

She paused, and eventually, her dog at her side, 2walked over the shingle and stopped. She examined the thing at her feet.

She’d taken it for a bird, but it wasn’t a bird.

What she’d thought were seagull wings was a grey hoody with white sleeves.

And, lit by the pretty lamps behind her, was a body, drifting in and out, in and out.

Chapter 1

White sludge is collecting on the windscreen wipers. The excited me is hoping it’s snow, the sensible me is reckoning it’s chubby rain. “Sleet”, Dad calls it. Whatever it is, the car chucks it off the side and we wind on south through the waterlogged lanes, heading for Christmas.

It’s a touch early to call it Christmas; right now we’re on our way to Grandpa’s birthday – he’ll be seventy – but we’re staying on for Christmas.

“Sheesh!” Dad yanks the steering wheel over and we skim the hedge as a silver van overtakes us in the 4shortest of straight stretches. “Total maniac!”

I clear a small circle on the glass and stare sideways at the wet countryside. It would look amazing covered in snow. “Dad? What’s it like when the sea’s covered in snow?”

“Pass,” he says. And then he says. “It wouldn’t be. It’s salty.”

Dad’s a scientist. An environmental one. We have only come by car because I begged. Otherwise it was the bus. And the train. And another train. And another bus. Apparently it would have done wonders for our family’s carbon footprint. I feel guilty, but it is Christmas.

“I wonder if they’ve got a tree yet?” he says as we whizz past a track entrance with a hand-painted sign offering Christmas trees and turkeys. I imagine a massive tree covered in coloured lights, baubles on every branch.

“We’re halfway through December. Grandpa and Queenie will have done that – won’t they?”

Dad nods and reaches for the radio button. “All I want…” he sings in off-key falsetto, and I join in, “…is yooooooooou.”

My heart lifts. It’s lovely being with Dad. Just 5Dad. It hardly ever happens any more and it won’t last much longer so I’m determined to make the most of it.

We yowl all the way along the twisty-turny road until we come to three vehicles half blocking the way. In front of the nearest car is the van that nearly killed us. The front wheel is in the ditch.

The third car is untouched. Two women glare through the windscreen.

By the van, there are two men shouting at each other and a woman in the middle waving her arms at them.

“Do you think they’re all right?”

Dad slows the car and nearly stops. I wind down the window so I can see better.

“I don’t think it’s anything a tow truck won’t fix.”

“But they might kill each other.”

“Nah, not in Somerset.”

I take a good look at all the people. The man leaning on the bonnet of the van, arms crossed, bearded, is radiating aggression. He’s wearing a heavy jacket with loads of pockets, which makes him look bigger, but the man hiding behind the door of the car is small and mean-looking and I 6reckon he’d probably win in a fight. The woman’s obviously with the van driver; they’re wearing the same boots. She looks like my maths teacher from school. Hair tied back, neat, She’s touching the big guy’s sleeve, trying to calm him down, and there’s a third man, much younger, with a blue and maroon football scarf, sitting in the van flicking through his phone.

When we’re nearly past, I take a picture on my phone. Not sure why.

“Karma,” says Dad. “Gonna be a right pain getting that wheel out of the ditch.”

We wriggle past and we sing and I Google-Map-read all the way to Lyme Regis, where the sludge on the windscreen definitely changes to snow. For a second. I’d swear.

Chapter 2

The snow has definitely stopped. We park in a big car park at the end of the seafront, miles from the house and I drag Tina (my stepmum)’s borrowed orange suitcase along the lumpy tarmac. It’s got a wheel that points the wrong way, jamming it in every crack in the path.

Although I have stolen her suitcase, we have left Tina behind with her sister. She’s having a baby on the first of January and she says she doesn’t want to share an uncomfortable rented house with Dad’s family when she’s the size of a Zeppelin and only 8wants to eat cheese and watch TV. She might also be being sensitive to me. I can’t work it out, but I’m happy it turned out that way.

She’ll come here for actual Christmas though, Zeppelin or not.

“When’s Edwin coming?” I ask, lifting the suitcase and carrying it. They’re embarrassing things. Everyone looks at you, even if they’re not orange. I should have taken something smaller.

“Tonight, I think. Depends on flights.”

Edwin is my totally excellent uncle. He lives in America. We haven’t seen him for a year, but we video call quite a lot, when he’s got time. He’s very busy.

Dad turns and loads his huge floppy backpack on me and takes my suitcase in exchange. “So there’s me and you, Grandpa and Queenie, Edwin, and Charlotte and … thingy and doodah.”

We’re two halves of a stepfamily joining together. Queenie’s not Dad’s mum. She’s his stepmum. She’s pretty good. She’s made a massive effort with me. Me and Dad both have stepmums but Dad only got his in the summer when Grandpa and Queenie got married. Charlotte is Dad’s new 9stepsister. Queenie’s daughter. I don’t really know her. She writes vegan recipe books and is obsessed with food, although the food can be weird. Her children are Storm, a wild toddler. He’s fun and very good at LEGO. And Isla, same age as me, not fun.

The thought of Isla dents my Christmas joy. I’ve tangled with her before. She’s home educated and she’s honestly clever enough to be on UniversityChallenge. She’s terrifying and a child genius. I will have to avoid being with her on our own. In an ideal world, it would be me and Dad, Edwin and Grandpa. Like Christmases used to be, but, as Dad says, things change.

“Will we all fit in the house?”

“It’s got an annexe. I think Edwin gets to stay in that.”

We bump out of the car park. The harbour and the Cobb on our right, the town rising up on our left.

“Is it one of these?” I say, as we pass the amusement arcade and trek along the seafront towards the amazing old houses facing out to sea.

“Yup!” he says. “The house is called Wintertide. 10The rent’s an absolute fortune, but Queenie paid for most of it. Edwin and I chipped in the rest. Now, which one is it?”

“Grandpa’s worth it,” I say, waiting while Dad checks his phone.

“Here,” he says, pointing up at a white-painted house with tiny square-pane windows and a big old front door looking straight out to sea. “Magic, isn’t it?”

Queenie welcomes us inside through a cloud of perfume and kisses, and we follow her up the winding stairs to our tiny room at the top.

“Charming,” says Dad, without a trace of irony. “Look at the angles on those roofs.” He waves at the view of walls and slate. “Just lovely.”

Luckily, it’s two single beds. I’d been imagining sharing the bed with Dad. He’s not small and he snores.

I sit on my bed; it’s under the window and kind of cute. I wonder how it’s going to work when Tina comes for Christmas. Where will I go? I’m sure Queenie’s thought about it. She’s the kind of person who does, but still…

“Where’s the Wi-Fi?” says Dad. “Never any 11signal here. Better check in with Tina. Go and find the router, George, love. I’ll stow this lot.”

I leave Dad unpacking and head off to search the house for the router. It gives me the excuse to push open all the other doors. There’s a big room at the front – Grandpa and Queenie. Another room to the right – Charlotte and Storm. I can tell it’s Storm by the collection of dinosaurs tucked up in bed. A bathroom. And then a tiny room with a little oval window looking out to sea and a high bed tucked up above a chest of drawers. Something like a cabin on a boat. Some orange trousers and a pink sweater are folded neatly on the chair. Isla. We have so little in common. She wears orange, the colour of Tina’s suitcase, and I wear black. And I have to admit that I am miffed that she has this excellent room.

As I stand in the doorway I hear feet pad on the stairs and before I can clear the landing, Isla appears.

She tilts her head and stares at me with her clear brown eyes. It’s not an accusation but I feel pretty uncomfortable. I mean, I am in her room.12

“Looking for the router,” I say, aware that it sounds feeble.

“Downstairs.” She points. “Hello,” she says. “I’m Isla – remember?” Her slight frown stretches into a smile. “We met before?”

“Mm,” I mumble, and duck off down the stairs before she can interrogate me. Of course we’ve met before – and last time I couldn’t think of anything to say either. I’m just so bad at her.

Luckily, things after that are a whirl. Hot drinks, instructions about fridges and meat that I do not pretend to understand, and then Dad and me and Queenie are sitting in the amazing front room, looking out to sea, heavy winter skies over steely grey sea, inside the house all cosy and warm.

“Cream on that?” says Queenie, holding out a hot chocolate.

“Of course he wants cream.”

I turn. “Grandpa!”

“George!” Grandpa drops his coat over the sofa and reaches out to hug me.

“Grandpa.” I feel the warmth of his arms and sink into them. Grandpa has always been there. He’s a rock. A totally solid being in my life, and 13he’s funny and wise.

“Thank you, lad – I know it’s a lot to drag you from your friends, especially at this time of year.”

“Oh, no, Grandpa, I wouldn’t miss this.” I laugh. “It was brilliant that school closed early.”

“Dodgy concrete?”

“Yup,” I say, remembering the moment when a huge lump of plaster fell in the middle of assembly, just missing Mr Pease, who was halfway through an exceptionally boring talk about tree stumps which was supposed to make us understand something about aspiration. I think. “Very dodgy.”

“Neeeeowwww!”

Storm. Holding a small aeroplane he charges into the room, circles it and charges out again, racing up the stairs.

“Oh, message from Tina – give me a moment,” says Dad.

Tina again. He could give it a few hours off – couldn’t he? I know the baby’s going to be a big thing in our lives, but quality time with Dad is kind of why I was looking forward to being here. Soon it’s going to be four of us at home. I’ll be so much older than the baby, I might as well be an uncle.14

I mean, it’s going to be years before the baby can even play Mario Kart.

Leaving Dad on his phone, I explore the rest of the house. It turns out there’s a basement – four dark rooms: a cobwebby toilet, a huge wet room, a room that smells of mushrooms and mice heaped with coal and old newspapers, and the fourth, windowless, painted pale pink with a vase of fake flowers and the saddest single bed in the world. Is this where I’ll be when Tina comes?

I also find the giant Christmas tree. It’s leaning in the wet room, all fresh and springy and smelling of pine. Or that could be someone’s shampoo.

I head back up to Dad. But guess who’s coming down? Isla, carrying a bag of toiletries – and we stand facing each other on the stairs.

“You’re going to have to talk to me eventually,” she says, dragging a comb through her bird’s-nest hair.

I open my mouth. Anything I can think of saying is going to be stupid. So I close it again.

“Please yourself,” she says and whisks on past me to the spidery depths below.

Chapter 3

“When are we putting up the tree?” I ask a little later.

“You could give me a hand with getting the stand, and the decorations, George,” says Queenie. “They’re in the car.”

Charlotte is making something complicated in the kitchen. It seems to involve a blender that goes off every minute or so. It’s actually maddening.

“Haven’t you done with that?” calls Queenie.

“Sorry,” Charlotte says. “I’ve the cashews to go.”

“Why don’t you two do the tree together?” says 16Dad, typing yet another message. He means me and Isla.

Isla is sitting at the end of the kitchen bench reading a book the size of a brick. She doesn’t look up.

“I don’t mind doing it on my own,” I say. “Or you could help me, Dad.”

“White lights?” says Isla.

Queenie pinches her lips and smiles to herself.

I don’t say anything. I prefer coloured lights. The pine fronds and the coloured lights together is one of my earliest memories. Looking up at the red and green reflecting from a bauble reminds me of being very small and feeling very safe, tucked between Dad and Edwin, with Grandpa telling stories about every decoration as Dad hung them on the tree.

“Come on, let’s do it now,” says Queenie, touching my elbow.

I put on my coat and we step out on to the promenade. It’s not quite dark when you’re outside, but it’s very cold. The wind weaves its way down my neck.

“Ooh, bitter,” says Queenie. She stops by the 17door that’s next to our front door and lifts the mat. There’s a key lying underneath. “Annexe,” she explains. “Just checking, in case Edwin arrives in the night.” We stomp along to the small car park at the end. “Ignore Isla, she’s … tricky, and, just so you know, we’ve got coloured lights.”

“Yes!” I fist pump. “I don’t know why it’s so important to me,” I say.

“Funny, isn’t it? It’s important to me too – my father used to fix the lights every Christmas. He’d swear over them and struggle with the precious little bulbs; they were painted with colour then. They never worked until the last minute, and sometimes they smelled alarmingly fishy, but there’s something about the dark green and the warm yellows. Lovely!”

She unlocks the boot of her car and I lift out a heavy iron lump. It has Treesploshed in red paint across the bottom of it in Grandpa’s writing. I’ve seen it every year since I can remember. I think of it in Grandpa’s cottage, the tree jammed up against the window. It’s funny seeing it out here in the open. It’s also funny not to be in Grandpa’s cottage just up the hill, but there wouldn’t be room for all of 18us. I clutch it to my chest. While Queenie looks in various boxes to find the ones full of decorations, I look out to sea.

Pretty spiral street lamps shaped like ammonites line the promenade, and beyond is the darkness of the water.

At the far end, the walled harbour with the aquarium where I once saw a sea mouse with Grandpa is outlined in white lights, as if someone’s drawn a neon building on the landscape.

Off to the left, the lights of the pub and then the black cliffs of Charmouth. And out there, bobbing in the dark, is a fishing boat.

It’s as if the world cuts off at that point. There’s nothing beyond. Except. Up to the far left, where there’s really nothing at all, nothing but the sky, there’s a light.

I stare at it. It’s moving, and then there’s a second one next to it. “What’s…”

As I look, the first light falls. “Whoa!”

And then it disappears.

“Did you see that?”

“What, darling?” Queenie slams the boot.

“That – up there? A light – it’s like it fell out 19of the sky.”

She wrinkles her nose and peers. “What are you looking at? Oh, yes.” Then the second light vanishes. I stare but I don’t see it again.

“Did you see it at all?” I ask.

Queenie rearranges the boxes of decorations so they fit under her arm. “Not your falling light. The other one was probably someone on the golf course, with a powerful torch.”

“What, like someone dropped one off the cliff?”

“Hmmm,” she says. “A Christmas mystery, eh?” She begins to walk back towards the house. “Look! Snow!”

“Oh, wow!” I say, tilting my face upwards. I can feel the icy dots pinging off my cheeks.

“Isn’t that wonderful!” she says, laughing her full-throated laugh. “The final ingredient!”

We half run, half walk back towards the house. By the time we reach the front door and drag the others out on to the pavement, it’s a proper blizzard.

“Yay!” yells Dad, and for a few minutes we dance outside, feeling the snowflakes on our faces and watching them bucket down around the ammonite lamps that line the promenade. It’s so pretty, and 20it does that weird snow thing of silencing the world so the amusement arcade music sounds like it’s a million miles away and the sea seems totally still.

“Food!” shouts Charlotte from the door, and with the promise that we’ll have a snowball fight after supper, we pile indoors.

The food is unappealing. Isla’s favourite, apparently. Something white in something white. With peas. Queenie takes a mouthful and swallows carefully.

“Quite nice, actually,” she says, and we all dive in.

It’s OK. Luckily Grandpa has made a chocolate sponge pudding, which is sensational, and I pile in to that. Looking sad, Charlotte refuses it for her herself and Storm, but Isla demolishes a massive plateful.

We sit at opposite ends and I listen to everyone’s conversation. I should manage to get on with Isla, I just don’t know where to start. Right now, she’s telling Dad that the planets aren’t the colours we think they are, and that the breed of sheep called Soay don’t live on the Isle of Soay, they come from St Kilda’s. I can’t imagine that she’s going to want 21to discuss Marvel movies, or D&D, or Bristol City’s new striker.

“That was delicious,” announces Queenie. “Top marks, cooks. Now, tree?”

While everyone argues about the position of the tree, I lug the stand from the hall. Dad collects the tree from the wet room and together we slot it into the stand and thread the lights through the branches. It’s massive. It almost reaches the lumpy old ceiling above us.

“Don’t forget water,” says Charlotte, stroking the branches and turning her back while licking the spoon from the chocolate sponge. “It’s a living thing.”

There’s a blissful half hour as Dad and I thread the baubles on to the tree, taking them from both boxes – Queenie’s and Grandpa’s – while listening to the burble of conversation behind us.

“Remember this one?” says Dad, holding up an embroidered turquoise goat. “It’s not a Christmas decoration, but you insisted.” He laughs and hangs it near the top.

“It is a decoration, Dad – you’re just old with a closed mind,” I reply.22

We laugh and plunge our hands back into the boxes.

Underneath the “good” decorations, I find the odder ones. This tree is tall; we’re going to have to use everything. At the bottom of Grandpa’s box there are little clip-on birds with threadbare brush tails, and tarnished baubles that have lost their string with starbursts of gold cut into the side of them. In Queenie’s, I find some straw figures that she says Charlotte made when she was six. They might be part of something much more sinister but placed in the branches are almost cute.

“Ready?” says Queenie, plugging in the lights behind the curtain.

I nod and she switches on, and for a moment I just stare. It’s lovely. It does all the Christmas things.

“Liiiiights. Tree!” shouts Storm, running towards it, then he stops and gazes with a huge smile on his face. “Pretty!”

“Yes, Storm,” says Queenie, wiping a tear. “Christmas lights. Aren’t they the best?”

She gives me and Storm a Queenie hug, all perfume and hairspray. “You’ve done a beautiful 23job, George. Now, snowball fight! I’ll do the washing up,” she whispers.

“Don’t think you’re going anywhere,” says Grandpa from the bay window of the sitting room. “Look, down there.”

I run to crouch on the window seat alongside him looking towards a blue flashing light that’s appeared at the end of the promenade. Two silhouettes with big torches are walking towards us. The snow, still falling fast, is blurring the view. Police? Here? Now?

“They’re heading to the beach.”

Torch beams play on the shingle, catching the splots of snow and confusing the scene.

Suddenly, Grandpa straightens up and begins to lower the blind.

“Why?” I say. “It was just getting interesting.”

“Exactly,” he says. “Now, who’s for a game of ludo?”

Chapter 4

Luckily, this house has an upstairs.

Dad gets there first and we stare out of Queenie and Grandpa’s bedroom window.

It’s a light show. Blue reflects off every surface outside and, fractured by the snow, bounces back into the room. A white tent goes up. Bright white lights appear on the beach. Blue tape seals off the railings from gawkers, but here we have front-row seats. This is not what I was expecting. I don’t know what’s going on, but I want to know.

“What’s in that tent?” asks Dad, checking his 25phone and peering into the blizzard outside.

“I give up,” Grandpa calls up the stairs. “You can come and watch from down here.”

We run down and everyone kneels on the window seat, noses pressed to the glass. Except for Isla.

I’m guessing that gawping at the police isn’t enough of an intellectual challenge.

Storm watches and then races off around the room. “Nee-naw, nee-naw,” he sings.

Grandpa, holding a mug of tea, starts a running commentary.

“Another crew’s turned up. Forensics, I think. Or possibly more CID. I wonder what it is – shall I go and ask?”

“Maybe it’s an unexploded bomb. They’re always turning up on beaches,” says Queenie.

“The army would be here,” says Grandpa. “Oh, there’s a downtrodden bloke walking towards us. Plain clothes. Ready, all?”

There’s a knock at the door. A police officer but not in uniform. We peel away from the window, everyone looking at the floor, as if we shouldn’t have been looking out. But it’s human nature to take an interest, isn’t it? And I am interested. At the 26back of my mind, I’m wondering if it has anything to do with the light I saw falling.

The man introduces himself as Detective Chief Inspector Parsons. He’s old – not as old as Grandpa, but much older than Dad. He sinks slowly on to the sofa as if he hasn’t sat down in months.

“Right,” he says. “Right. Now.”

“Would you like a cup of tea?” asks Dad. “You must be frozen.”

Grandpa sits down opposite the police officer. Dad hovers uncertainly near the kettle and in the end decides to switch it on, so the room fills with the sound of the kettle heating up.

I perch on the arm of Grandpa’s sofa, waiting. The man shakes off his jacket. “Lovely and warm in here,” he mutters, before launching into a string of questions. “Do you live here then?”

“It’s a holiday cottage,” says Queenie, “but we live in the town. Can we help?”

“For Christmas?”

“Ten days. My dad’s birthday,” chips in Dad. Grandpa points at himself. “And Christmas.”

“Not what you need then, bodies washing up 27on the beach, oh, no, sir.” DCI Parsons clears his throat.

“Bodies?” says Grandpa.

“Shouldn’t have said that,” says DCI Parsons, but he glances up to see everyone’s reactions.

“Oh dear,” says Charlotte.

“Well, one,” corrects the DCI. “Did any of you see anything? Anything at all?”

“Yes!” I interrupt the murmur in the room. “I saw a light that fell!”

Everyone turns to stare at me.

Even Isla puts her book down and fixes me with her gaze, like a robin eyeing a worm.

“When we went to get the decorations – Queenie and me. I saw a light fall off the cliff. Or, out of the sky.”

“Not a firework, laddie?” says Grandpa.

I shake my head. “No. It fell too fast.”

“I didn’t see the falling light,” says Queenie, “but I did see a light up there.”

“Where?” asks Grandpa.

“Golf course?” she says.

The policeman tilts his head. “How – too fast, laddie?”28

“Well, like someone dropping something. A firework sort of pauses, before falling.”

Dad nods his head. “Right, that.”

“How long ago?”

Queenie and I look at each other. “Three hours? Maybe?”

DCI Parsons writes something in his notebook. “That tallies. Anyway, thank you for your time. Sorry to disturb your birthday trip, sir.” He stands and runs his fingers through his six strands of hair before jamming an old man’s hat on top.

“Who is the poor soul?” asks Queenie.

“And who was the poor soul who found them? Awful!” says Grandpa.

It’s the DCI’s turn to shake his head. “No idea at this stage – that’s all … you know … in the future. And a dog walker – she’s receiving counselling. She thought… Yes… Anyway…”

I wonder what she thought, but I’m not going to ask.

“Anything we can do to help?” says Grandpa, seeing him into the hallway.

“Could the lights I saw be connected?” I ask, cramming alongside Grandpa.29

The DCI turns in the doorway. “Thank you for your help,” he repeats, and he steps out into the snow.

“Right,” says Grandpa, coming back into the room rubbing his hands. “Monopoly, anyone?”

Feeling somehow fobbed off, I join in with the game. No one mentions the body on the beach. Or my falling light. They just go on as if nothing has happened. So I do too, although I keep on thinking about it.