Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

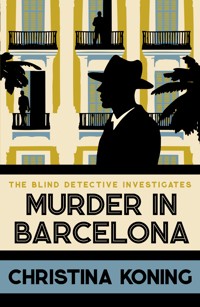

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Blind Detective

- Sprache: Englisch

'With vivid characterisation and a keen ear for dialogue, Christina Koning has all the qualities of a first-class mystery writer.' - DAILY MAIL First published as Twist of Fate under A. C. Koning. Summer, 1937. Frederick Rowlands' peaceful holiday in Cornwall is derailed when a film star is found dead in his hotel. The suspicious nature of Dolores La Mar's death points to murder and Rowlands soon finds himself caught up in the police investigation. When his old flame, Secret Service agent Iris Barnes arrives, it transpires that the killing has links to the political turmoil of the Spanish Civil War. Rowlands and Barnes begin to follow a treacherous trail of Republican revolutionaries which leads them to the dark streets of Barcelona, where they discover that their Cornish murder is more connected to the city than either of them realised. As Europe inches closer towards international conflict, will Rowlands and Barnes make it out of Spain alive?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 468

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

MURDER IN BARCELONA

CHRISTINAKONING

For James and Marina

Contents

Chapter One

‘I must say I’m terrified,’ said Cecily Nicholls. ‘I mean – what do you think film stars eat?’

‘Not very much, from what I can gather,’ was her brother’s reply. ‘Aren’t they always banting?’

‘Worse and worse,’ said Mrs Nicholls. ‘What am I going to feed them?’

‘I should give them just what you give everyone else,’ said Frederick Rowlands, from his seat in the big bay window with its panoramic view of the sea. Not that he could see the view, of course, but he could hear the soft swishing of the waves as they fell against the shore, and smell the faint tang of salt and ozone. ‘Delicious home-cooked food, made with fresh produce from local farms and fishermen. They’ll eat it up – quite literally!’

‘I hope you’re right,’ said his hostess. ‘Honestly, I’m beginning to wish I’d never accepted this booking.’

‘I can’t think why you did,’ said Jack Ashenhurst mildly. ‘Since it’s giving you such a headache.’

‘Bookings are down this year,’ his sister reminded him. ‘And we’ve had several cancellations. People just don’t have the money to spare.’

‘I realise that. But surely, the regulars …’

‘The Pollards have cried off. Her mother’s ill. And Colonel and Mrs Rutherford have booked for two weeks, instead of their usual three.’

‘All right, all right, I get it,’ said Ashenhurst, with a groan of comic despair. ‘So these film people are really our saviours, in a way?’

‘I suppose so.’ Mrs Nicholls didn’t sound convinced. Ashenhurst did his best to rally her, ‘Come on, old thing! We’ve had large bookings before. Remember that time they held the regatta off Lizard Point? We were booked solid for ten days.’

‘It isn’t the numbers as such,’ said his sister. ‘It’s … Here, I’ll read you what Miss Brierley’s letter says.’

‘Who’s Miss Brierley when she’s at home?’

‘She’s secretary to Miss La Mar. Dolores La Mar,’ she added, as if this ought to mean something to him. ‘The sultry temptress with the dark brown voice.’

‘Never heard of her.’

‘Jack! Surely even you …’

‘She was in Spurned Lovers, opposite Marcus Mandeville,’ put in Edith, who had been sewing name tags on her youngest daughter’s gym kit. ‘I thought she was rather good, actually. Fred enjoyed it, too – didn’t you?’

‘Leave me out of it,’ laughed her husband. ‘I’m not a good judge of actresses, these days.’

‘Well, this one sounds like a prima donna,’ said Mrs Nicholls. ‘Listen to this: “On days when she is filming, Miss La Mar will require breakfast at six a.m., consisting of two soft-boiled eggs, one slice of thinly buttered toast, which must be hot, and a cup of very weak tea without milk (lemon is preferred). Her bath should be drawn at half past six, and a fire (laid the previous night) lit in time for her to dress (her maid will assist her with dressing, and must therefore be allocated a room next to Miss La Mar’s). She will require a cup of hot, strong coffee without milk or sugar while she is waiting for the car to arrive at seven a.m. When she returns from a day’s filming, she will require the water to be hot for her bath, and a fire to be lit in her room, as per instructions. On days when she is not called until later, she will rest in her room, or on the terrace set aside for her exclusive use, until such time as shooting is set to begin. She must on no account be disturbed during these hours as she will need peace and quiet in order to learn her lines and to get into the right frame of mind for the day’s filming schedule …” There’s more,’ she added gloomily. ‘But you get the general idea.’

‘I’ll say! She sounds like a perfect tyrant,’ said Dorothy Ashenhurst, coming in at this moment. Her brother begged to differ.

‘I should have said it was all fairly routine stuff myself,’ he said. ‘Most actresses need to prepare, and as for the stipulations about breakfast, I have to say I agree with her. Nothing worse than cold toast and weak coffee.’

‘Oh, we all know that you’re familiar with the film star type,’ laughed Jack Ashenhurst. ‘What was the name of that glamorous femme fatale you got so pally with in Berlin?’

‘I suppose you mean Magdalena Brandt,’ was the reply. ‘And I was hardly pally with her. We met a few times, that’s all.’ Which wasn’t quite the whole truth, but Rowlands had found it expedient to say as little as possible on the subject of his relations with the lovely star of the German cinema.

‘Even so, it’s given you an insight into how these film types behave,’ said his friend. ‘I vote we assign special duties as regards Miss Dolores La Mar – or whatever her name is – to Fred.’

‘Thank you very much,’ said Rowlands. ‘But I’ll have you know that I’m here on holiday. I’m going to do nothing for the next two weeks but eat, sleep and go for an occasional gentle stroll with my wife along the clifftops, if it’s all the same to you.’

But in that fervently expressed wish he was, as it turned out, to be disappointed.

Rowlands was two days into his annual holiday, having joined his wife and daughters at the Cornish hotel run by his friend and brother-in-law, Jack Ashenhurst. The holiday had become something of a fixture in the Rowlands’ family calendar – a welcome break from London and the pressures of working life, as well as a chance to escape, if only for a time, from greater worries. The news from Germany was as disturbing as ever, but it was Spain which had been most in the news, these past few weeks – displacing even the coverage of the coronation, which had taken place in May, and which had itself dislodged the abdication scandal from the front pages.

As he had been packing his suitcase for the holiday, Rowlands had heard the news on the wireless about the bombing of Madrid by Falangist artillery. Given that the Nationalists were being openly supported by Hitler, who’d authorised the bombing of Guernica by the Luftwaffe a few months before, things were starting to look very nasty indeed, he thought. ‘A penny for them,’ said his wife, who had left her seat on the far side of the hotel lounge and now stood beside him. For a moment, she rested her hand on his shoulder.

‘You wouldn’t want to know,’ he replied, keeping his voice light. But Edith knew him too well to be fobbed off.

‘I thought we’d agreed that you’d put work out of your mind for the next few weeks,’ she said. ‘Leave worrying about finances to Sir Ian.’

In his capacity as Secretary to St Dunstan’s, the institute for the war-blinded, of which he had been a member since being invalided out of the army in 1917, Rowlands was all too familiar with the claims being made on the organisation’s resources – at present stretched to the limit because of building the new centre at Ovingdean. ‘I wasn’t thinking about work – or not only that,’ he said. Because of course the question of whether – or rather, when – there would be another war was one in which he and his fellow St Dunstaners took a passionate interest. For men of their generation, who had been through one war, the prospect of another was intolerable. Some of them had sons who’d be of an age to fight, if it came to that. Not for the first time, Rowlands thanked his stars that he had daughters.

‘Well, whatever it is, try and forget about it while you’re here,’ said Edith. ‘You’ll do no good to anyone, fretting about what you can’t change.’

‘Just as well not everybody thinks like that,’ muttered Rowlands’ sister, who never could let an opportunity pass for making a political point. ‘Otherwise the Republicans would have been crushed by those Fascist bullies a long time ago.’ Rowlands groaned to himself. Dorothy had never outgrown the revolutionary zeal to which she’d adhered as a girl. Not that she was alone in idealising the Republican cause, or in hero-worshipping those who’d gone to fight for the International Brigades. Edith could be no less stubborn when it came to defending her own point of view.

‘You surely can’t believe that a few hotheads playing at soldiers can make that much of difference?’

‘Hotheads! These are men – and women, too – who are prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice for what they think is right.’

‘And what of their families?’ said Edith. ‘Do they have to make the ultimate sacrifice, too? Some of your brave soldiers are little more than children. How would you feel if Billy decided to run off to Spain?’

‘Happily, that’s an academic question,’ put in Jack quickly. Six years of being married to Dorothy had made him adept at heading off contentious topics. ‘If we’re expecting these film people the day after tomorrow, hadn’t we better make sure everything’s ready for them? Dottie, you’re in charge of allocating rooms. Ciss,’ – this was to his sister – ‘you’d better run through the week’s menus again with Mrs Jago. I’ll handle the drinks side of things. I gather these people like their cocktails, so I’d better check that there’s plenty of gin. Come on. We’ve no time to sit around jawing about the problems of the world. We’ve a hotel to run.’

They were just sitting down in the hotel lounge for a preprandial glass of sherry on the day in question when a powerful motor car – a Rolls-Royce from the sound of it, thought Rowlands – drew up in the courtyard outside. A moment later, Danny, the Ashenhursts’ adopted son, rushed into the room, followed by his brothers, Billy and Victor. ‘Dad …’ he said excitedly.

‘I know, old man,’ said Jack, getting to his feet. ‘This will be the new lot of guests. And do try not to run,’ he added as the three boys clattered out into the hall to inspect the arrivals, or rather, the vehicle in which they had arrived, thought Rowlands, smiling to himself. Walter Metzner, who at sixteen perhaps considered himself too grown-up to get excited about a car, joined the adults in the room at that moment, with the Rowlandses’ three girls.

Voices were heard in the hall, Jack’s amongst them, as he welcomed the arrivals to Cliff House. ‘But this is charming!’ cried a woman – the famous Dolores La Mar, Rowlands assumed. ‘Quite remote and rustic, don’t you think, Horace?’ A moment later, the lady made her entrance in a cloud of Joy, followed by some of the other members of her party. ‘Why, you didn’t tell me there’d be young people!’ she exclaimed from the doorway (‘Where she stood looking like Theda Bara, draped from top to toe in mink,’ said Edith afterwards). Miss La Mar’s remark was evidently addressed to her secretary – Miss Brierley, of the letter – since it was she who replied, with some embarrassment, ‘Oh! I didn’t know … That is … I didn’t think to enquire.’

‘I’m sure the young people will keep to their own part of the hotel,’ said Cecily Nicholls quickly. ‘And we’ve agreed that the tennis court nearest your windows should be out of bounds.’

‘But this is too bad!’ cried the actress. Rowlands wondered whether her accent was American or something more exotic. ‘For the young people to be kept from their amusements on my account. Come, introduce me,’ she added, with the faintly peremptory note that showed she was used to having her commands obeyed.

‘Well, I’m Cecily Nicholls, and this is my brother Jack Ashenhurst, whom you’ve met, of course …’

‘I meant the children,’ interrupted Miss La Mar, with the mixture of playfulness and steely determination to have her way which Rowlands guessed was her modus operandi. ‘It’s the children I want to meet.’ Then, with a cooing laugh, to mitigate her rudeness, ‘There’ll be time enough for the rest of us to get acquainted. Horace – my husband – will tell me who you all are, won’t you, my sweet?’

‘Rather,’ said the man Rowlands assumed must be the film star’s husband, stepping forward to shake hands with Ashenhurst, and then with Rowlands. ‘Name’s Cunningham,’ he said. ‘How d’you do?’ From this brief contact, Rowlands received the impression of a man no longer young, but still upright and vigorous. A force to be reckoned with in spite of his seeming reticence. Although anyone would seem subdued beside the ebullient Miss La Mar. This must be the Horace Cunningham whose name appeared with some regularity in the financial columns of the newspaper, thought Rowlands, not that he himself took much of an interest in those, but Edith had inherited some shares from her father, and so her daily reading aloud of the paper sometimes took in what was happening in the City and on Wall Street. Cunningham was in steel, wasn’t he – or was it railways? Probably both, thought Rowlands, his attention momentarily diverted from the comedy that was being played out in the hotel lounge.

‘Such charming girls!’ Dolores La Mar was exclaiming as Rowlands’ daughters were presented to her. ‘What are your names, dears?’ When she was told, she gave another little cry. ‘Margaret! How perfectly sweet! Now, let me guess … you’re the clever one. And you,’ – this was to Anne, the Rowlands middle child – ‘you must be the pretty one. Which leaves you’ – this was ten-year-old Joan – ‘as the pet of the family. Am I right?’ She gave a gurgling laugh. ‘Of course I am.’

What a performance, thought Rowlands, not without a certain grudging admiration at the way the prima donna was getting them all to eat out of her hand. Although he and Edith had never encouraged such labels – the ‘pretty one’, forsooth! All his daughters were beautiful, to his mind, and clever, too. He didn’t need some superannuated starlet to tell him so. Having disposed of the Rowlands girls, Dolores La Mar had moved onto the Ashenhursts’ three sons and their cousin. ‘Now, don’t tell me … you must be the eldest, to judge from your height.’ She must be addressing Billy, who had put on a growth spurt recently, Rowlands knew. ‘What a tall young man! You must be six foot.’

‘As a matter of fact,’ said Walter Metzner, in his clear, almost unaccented English, ‘I am the eldest. My cousin is one year younger.’ Miss La Mar paid no attention to him, however, but turned her attention to the youngest member of the group.

‘I’d say you were related – this tall chap and yourself. You have a look of one another.’

‘He’s my brother,’ said Victor Ashenhurst. ‘I’m nine,’ he added proudly. ‘But I’m tall for my age.’

‘I can see that,’ said the actress, with her throaty laugh. ‘Well, perhaps you two tall fellows … and you,’ she added off-handedly to Danny, ‘will be terribly kind and bring in my luggage? There’s rather a mountain of it, I’m afraid. But I’m sure such big, strong boys will be up to it.’

‘My dear, Carlos will manage perfectly well,’ put in Cunningham. ‘Young Quayle can give him a hand,’ he added drily. But the boys were already out of the door, with their cousins in hot pursuit.

‘It’s a wizard car,’ Danny Ashenhurst could be heard enthusing. ‘A Phantom III with Mulliner coachwork – latest model. I saw one just like it in Practical Motorist – only midnight blue, not silver-grey.’

A brief silence fell. ‘Well,’ said Mrs Nicholls. ‘You’ll want to see your rooms, I expect. We’ve put you in the Blue Room – that’s the one with the best view of the sea,’ she added. ‘Your maid is in the dressing room next door, and Miss Brierley …’ But Dolores La Mar wasn’t interested in these arrangements.

‘Oh, Brierley will see to all that, won’t you, Brierley?’ she said to this factotum. ‘What I’d really like at this minute is a very dry martini. Travelling always gives one such a terrible thirst, don’t you find?’

‘I … ah … I’ll just fetch some ice,’ said Jack Ashenhurst, disappearing from the room. Another slightly awkward pause ensued before Miss La Mar went on, ‘I must say, this is all perfectly delightful. When Hilly – that’s my wonderful director, Hilary Carmody – told me the location shots for Forbidden Desires were to be filmed in Cornwall, I pictured something wild and dangerous. But this …’ She must have made some gesture to encompass the view from the window, ‘Is so peaceful.’

‘It does get quite wild during the winter months,’ said her hostess. ‘And I think the scenery along this coast is generally considered quite rugged.’

‘Oh, I leave all that sort of detail to Hilly,’ said the other with a laugh. ‘My job is just to turn up and deliver my lines.’

‘Which you do marvellously well, darling,’ said a voice from the doorway. ‘I say – I don’t suppose there’s one of those for me?’ Because Ashenhurst had by now returned with the ice and was busy measuring gin into a cocktail shaker before adding a dash of vermouth.

‘I hope a twist of lemon will do?’ he said to Miss La Mar once this operation was complete. ‘The local shop doesn’t stock olives.’

‘That’ll do fine.’ She took the drink from him without further ceremony and turned her attention to the newcomer. ‘I was wondering where you’d got to, Larry. You’ve been an age.’

‘I was helping to bring in the suitcases,’ was the affronted reply. ‘At least … I would have helped, but your chauffeur chappie said he could manage. And then a perfect horde of little boys rushed up and insisted on carrying things.’

‘I shouldn’t have thought you’d object to that, darling.’

While this inane chatter was going on, Ashenhurst was engaged in distributing drinks to the rest of the party. Cunningham refused a cocktail but said he’d have a whisky. Miss Brierley requested a sweet sherry. Only when these two had received their drinks, did he turn to the man to whom Dolores La Mar had been talking. ‘A dry martini, I think you said?’

‘Ooh, yes please! Laurence Quayle’s the name, by the way,’ added this ebullient young man. ‘But do call me Larry. Everybody else does.’

While these introductions were going on, Rowlands turned his attention to the man standing next to him. ‘Did you have a good journey down, Mr Cunningham?’

‘Not too bad, thanks,’ was the reply. ‘Of course, one can’t get up much speed after one descends into these Cornish lanes, but I’ve a competent driver, so …’ He let the sentence tail off, but the implication was clear. A man of his standing and financial worth needn’t trouble himself overmuch with what he paid others to do.

They were joined at that moment by the star, perhaps curious to inspect the man to whom she had not yet had cause to speak. It was possible, thought Rowlands with a certain wry amusement, that she was as yet unaware of how impervious he and Ashenhurst were to her more obvious charms. Of course, other things – not least a woman’s voice – could be powerfully seductive. So far, he had not found Dolores La Mar’s voice especially so. There was something too studied about her manner – hardly surprising in an actress, he supposed. Although he had known another actress whose voice had enchanted him even as he knew she was using it to get her own way. But then few women – whether actresses or not – could compare with Magdalena Brandt.

It seemed that Miss La Mar had picked up that at least one of those present had failed to succumb to her charm. ‘And you are?’ she said, addressing Rowlands in what he described to himself as ‘honeyed tones’. He introduced himself.

‘This is my wife, Edith,’ he added since the latter had now joined them. But the film star showed little interest in Edith.

‘You know,’ she murmured, still holding Rowlands’ hand in hers, ‘you look very familiar. Have we met?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Strange. I could have sworn …’

‘You might have seen Fred in pictures,’ put in Jack Ashenhurst, with a laugh. Rowlands could have clouted him.

‘Really?’ Suddenly she was interested. ‘You mean you’re an actor?’

‘No, no. My brother-in-law was joking.’

‘But you were in a film,’ insisted Ashenhurst. ‘You can’t deny it, old man.’

‘It was a very small, non-speaking role in a German production,’ said Rowlands with a shrug. ‘I’m not sure the film was ever released.’

But this was evidently enough to establish his credentials with Dolores La Mar. ‘I might have known you were an actor, with a face like yours,’ she said. ‘Rather distinguished. A good profile, too. I must ask Hilly if we can use you.’

‘No, please don’t …’ Rowlands started to say, but – as was her wont – she cut across him.

‘Only I will give you one tip – you must learn to look at the person you are addressing.’

Rowlands smiled. ‘I assure you, I would if I could,’ he said.

‘Well!’ was Edith’s muttered comment when, a few minutes later, their little party – summoned by the banging of a gong – was making its way towards the dining room. ‘Talk about vamping.’

‘Shh. She’ll hear you.’

‘She’s too busy listening to the sound of her own voice for that!’

‘Even so. Ah, good evening, Colonel … Mrs Rutherford.’ For he had heard that couple approaching – guests of long-standing at Cliff House Hotel.

‘Evening,’ was Colonel Rutherford’s gruff reply. He was retired Indian Army, with all that that implied about his bearing and manner. ‘By Jove! Who is that rather splendid gel?’

‘That’s Dolores La Mar.’ Then when this failed to elicit a response, Rowlands added, ‘She’s a film actress.’

‘Is she, by Gad? Handsome piece, saving your presence Milly.’ This was to his wife, whose only comment was a sniff. ‘Can’t say as I think much of that pansy she’s talking to. Actor, too, I shouldn’t wonder.’

‘I should think you’re right,’ said Rowlands. He and Edith and the girls took their places at their usual table next to the south-facing window where they were joined by Billy and Walter, while the Colonel and his lady made their way to a table in the bay window, exchanging murmured greetings with the Simkins family: Daphne and John, and their twin sons Jonathan and Rory, who were already seated. The Simkinses, too, had been coming to Cliff House for some years so that the boys had almost become members of the Ashenhurst–Rowlands tribe – a state of affairs made more interesting by the ‘understanding’ which had grown up between the eighteen-year-old Jonathan Simkins and Rowlands’ seventeen-year-old daughter, Margaret. Although in Rowlands’ opinion, she was too young for any such engagement, unofficial or otherwise. She still had her exams to do, and there was Cambridge Entrance looming, too.

At the big table along the far wall, the actors and their entourage had taken their seats, with Dolores La Mar at the centre, facing into the room. Her remarks were therefore impossible to ignore since, like all those of her profession, she had developed the art of projection. ‘Come and sit by me, Larry,’ she was saying. ‘Horace, you’re on my other side. I like to keep my men close by,’ she added, with what Rowlands suspected was her trademark gurgling laugh. ‘Brierley, you can sit next to Larry.’ It crossed Rowlands’ mind that by placing the secretary between Laurence Quayle and Dorothy, who was at the near end of the table, the actress was effectively preventing his good-looking sister from receiving any share of the young man’s attentions.

Not that it would bother Dorothy in the slightest: she’d made no secret of her disdain for ‘these acting types’, as she called them. ‘People who make a living out of pretending to be somebody else – what sort of job is that?’ she’d said when the question of how the film party was to be accommodated had been discussed a few days before.

‘I must say I think that’s rather unfair on actors,’ Jack had objected mildly. ‘They give pleasure to a lot of people.’

‘To say nothing of the way they – or rather, the films in which they act – can communicate ideas,’ put in Rowlands slyly. ‘I’m sure your friends in the Soviet Union would agree.’

‘They’re not my friends, as you call them,’ said his sister. ‘And I hardly think the kind of romantic tosh most of these film companies put out can compare with films designed to educate the masses.’

‘Propaganda, in a word,’ said Rowlands cheerfully. ‘No, thank goodness Elstree hasn’t so far stooped to that!’ To which the erstwhile champion of the Russian political experiment’s only reply was a contemptuous snort. Of late, Dorothy’s enthusiasm for the Communist regime had been noticeably less strident. Perhaps even she was beginning to realise that there was a difference between ideology and reality? Now, as the soup course was served (fifteen-year-old Jenny Penhaligon having being trained by her aunt, Mrs Jago, the hotel’s cook, in the niceties of waiting at table), Rowlands could hear his sister making a determined effort with Miss Brierley.

‘I hope you’re enjoying the soup? I made it myself, you know.’

‘Oh yes, it’s very nice.’

‘I always think a chilled soup is best on a summer’s evening, don’t you?’

‘Oh, yes.’ Rather a nervous young woman, thought Rowlands, although working for someone like Dolores La Mar would be enough to make anyone self-conscious. Further along the table, the conversation had turned to the whereabouts of the rest of the party.

‘I can’t think what’s happened to Hilly and Eliot,’ said Dolores La Mar. ‘They set out at the same time as we did.’

‘Yes, but in a far less powerful motor car,’ said Laurence Quayle. ‘You’ve grown so accustomed to the Rolls, darling, that you’ve forgotten what it’s like to rely on a car whose top speed barely reaches forty miles per hour.’

‘I’m glad to say I’ve never had to set foot in such a rattletrap,’ was the reply. ‘Why Hilly doesn’t get himself a better car, I can’t imagine.’

‘It isn’t Hilary’s car. It belongs to Miss Linden, as you well know,’ said Quayle, in the same tone of indulgent amusement with which he had received all the prima donna’s salvoes. ‘And she can’t afford anything better – not while she’s still earning the pittance Management pays her.’

‘She’s paid what Management thinks she’s worth,’ said Miss La Mar, a shade testily. ‘When she’s worked her way up to having her name at the top of the bill, she can think about trading in that horrible little car for a better one.’

‘Oh, we all know you’re the Rolls-Royce sort,’ said Quayle silkily. ‘Lucky for you that Horace here is so “oofy”, isn’t it, darling?’

‘I’ll have you know,’ said the actress, her voice rising, ‘that I was earning top rates long before I married – isn’t that so, Horace?’

‘Certainly, my dear.’

‘So you see it’s all nonsense about my relying on Horace’s money … Yes, yes. Take it away.’ This was to Jenny Penhaligon, who – nervous no doubt at her proximity to the star – was making a bit of a performance about collecting up the empty soup plates.

‘Won’t you have some of this lobster salad?’ Dorothy was saying to Miss Brierley. ‘It’s Mrs Jago’s speciality.’

‘Thank you, but I never eat fish,’ said the secretary, with a nervous little laugh. ‘The soup will do for me.’

‘But surely you’ll need more than that?’ said Dorothy. ‘I can have Cook make you an omelette, if you like.’

‘Oh, Brierley’s one of the nuts and beans brigade,’ sang out Dolores La Mar from along the table. ‘Never eats anything remotely edible, as far as I can tell. It’s why she looks so washed-out.’ Before she could elaborate on this theme, there came the sound of a car pulling up outside, followed by the slamming of car doors. A moment later, the late arrivals made their entrance.

‘Please don’t get up,’ said one of them – his deep, warm tones identifying him as a leading man, if ever there was one, thought Rowlands. ‘We’re abominably late, I’m afraid’.

Chapter Two

‘It’s all my fault,’ said another voice – a young woman’s – sounding cheerfully unrepentant. ‘I took a wrong turning after St Austell, and then my map-reader got us even more lost.’

‘I did not,’ said the Leading Man, with dignity. ‘You managed that perfectly well by yourself.’

‘Children, children!’ said a third member of the party. ‘Cease this unseemly squabbling at once, or our kind hostess will regret that she ever agreed to have us. Hilary Carmody,’ he added, to Cecily, who had risen with the others. ‘You must be Mrs Ashenhurst.’

‘Actually that’s me,’ said Dorothy. ‘This is Mrs Nicholls, my sister-in-law.’

‘Delighted to meet you both,’ was the affable reply. ‘So which of you gentlemen is Mr Ashenhurst? Since I seem fated to get people’s names mixed up this evening.’ Introductions were duly performed, and then the newcomers, consisting of Carmody, the leading man (whose name, it transpired, was Eliot Dean) and the young lady who’d been driving – a Miss Lydia Linden – took their seats on the opposite side of the table to Dolores La Mar and her consorts.

‘Well, you took your time,’ she said, addressing Dean, apparently, for he seized her hand across the table and kissed it.

‘Darling,’ he said. ‘Did you miss me so very much?’

‘Oh, we all miss your sparkling wit, don’t we, Horace?’

‘I couldn’t possibly comment,’ said Cunningham drily. ‘May I give you some wine, Miss Linden?’

‘Rather. I say, what scrumptious grub! I’m absolutely starving.’

The conversation was necessarily suspended while those still in need of a first course were hastily served, and those awaiting the boeuf en daube which was to follow it had their plates changed.

‘At last!’ said Dolores La Mar, not quite sotto voce. ‘Something hot.’ Fortunately the dish, when it came, was of a quality to silence even the most difficult to please, and for the next few minutes an appreciative silence reigned. When at last the talk at the big table resumed, it was of the arrangements for the rest of the film crew – cameramen and lighting technicians – for whom room could not be found at the Cliff House Hotel.

‘I always recommend the Paris Hotel if we’re full,’ said Ashenhurst. ‘They should be able to accommodate your people quite satisfactorily.’

‘The Paris Hotel?’ This was Miss La Mar. ‘I must say, I’m surprised that the budget stretches to that! And why wasn’t I given the choice? The Paris Hotel sounds rather more my thing than … well.’ She let the comment hang in the air. Really, thought Rowlands, half-amused and half-annoyed on his friends’ behalf. She really doesn’t care what she says, or whom she offends. It was explained to the actress that the Paris Hotel was in fact a decidedly rustic inn, named after a ship which had been wrecked on that rocky coastline at the end of the previous century.

‘So you see, it wouldn’t be at all your thing, darling,’ said Laurence Quayle fondly. ‘Unless you fancy roughing it with the locals.’

After dinner, the film party and their hosts retired to the lounge for coffee, leaving Jenny Penhaligon and her cousin Sally Trelawny (also drafted in for the summer season) to clear the tables. The Rowlands family followed suit. Even ten-year-old Joan was given permission by her mother to stay up an extra half-hour in order to share in the excitement of having real-life film stars on the premises. Although Joan’s taste in films ran more to Queen of the Jungle and King Solomon’s Mines than to the romantic productions in which, Rowlands supposed, Dolores La Mar and her colleagues displayed their talents.

His elder daughters seemed suitably captivated, however. ‘I think Miss La Mar’s frock is so elegant,’ breathed Anne, provoking the tart reply from her mother that she didn’t imagine oyster-coloured satin was the most practical wear for scrambling about the cliffs with a sketch pad (Anne’s favourite pastime, during these past weeks). Margaret, too, seemed somewhat overawed by the new arrivals, or by one of them in particular.

‘I must have seen every one of Eliot Dean’s films,’ Rowlands heard her say to Jonathan Simkins. ‘He was marvellous in Chance Encounter. But I think Strange Destinies is my favourite.’

‘He looks a lot older in the flesh than he does on the screen,’ was the disgruntled reply. ‘I suppose one’s seeing him without all that make-up.’ Rowlands suppressed a smile. Poor young Simkins was evidently feeling the pangs of jealousy. On the far side of the lounge, the prima donna was holding court on the chaise longue.

‘Come and sit by me, Eliot. Horace can sit over there, next to Brierley. You don’t mind do you, Horace? Eliot and I have things to discuss, and it’ll only bore you.’

Her co-star accordingly seated himself on her right-hand side. ‘Delightful spot, this,’ he said, presumably having taken in the view from the windows. ‘I shouldn’t mind a walk later, along the clifftops. Blow away the cobwebs after that infernal drive. There’s going to be a magnificent sunset, from the look of it.’ It really was a beautiful voice, thought Rowlands. Mellifluous, and yet indisputably masculine. If this was what star quality sounded like, he supposed Eliot Dean had it. ‘Ah, thank you,’ said the leading man to Dorothy, who’d just handed him a cup of coffee. ‘What do you say, Liddy? Fancy a walk?’

‘I don’t mind,’ was the reply. ‘Thanks. Two sugars, please.’ At least this one wasn’t watching her figure, thought Rowlands. ‘Yes, I’ll go with you,’ went on Miss Linden – for it was she. ‘Just as long as you don’t expect me to go very far. I’m simply longing for my bed.’

‘You can’t go to bed yet! It’s not half past nine. I thought you young people were supposed to be fresh air fiends.’

‘I can’t think where you got that idea,’ said Laurence Quayle, from the floor at Miss La Mar’s feet. He gave an affected little shudder. ‘This young person prefers his creature comforts. Catch me striding about on clifftops! No thank you very much.’

‘It’s funny,’ said Dean. ‘But I never think of you as young, Quayle. Although you can’t be more than – what? Twenty-five?’

‘I’m twenty-two. Yes, I suppose one must rather lose touch with what it’s like to be young once one enters middle age,’ said Quayle sweetly.

‘Middle age! I’ll have you know I’ll be thirty-five next birthday.’

‘Precisely,’ said Laurence Quayle. Rowlands wondered if the animosity implicit in his remark was real or put on for effect. It was hard to tell with actors.

‘I wouldn’t mind a walk,’ said Jonathan Simkins in an undertone to Margaret, who had been helping her aunt hand round the coffee cups, and now joined her family at the near end of the lounge. ‘Coming, Megs?’

‘No, thanks. Walter’ll go with you, won’t you, Walter? He was saying he felt like a breather.’

‘Ja, I will come with you. There will be a fine view of the moon in conjunction with Venus and Jupiter across the sea tonight, I think. The moon will be full tomorrow night and so …’ But Jonathan evidently didn’t care a hang about the moon, or Jupiter – at least, not if he had to see them with Walter Metzner rather than with his preferred companion.

‘I suppose,’ he said bitterly to Margaret, ‘you’d rather stay stuffed up in here?’

‘Yes,’ she said. Because across the room, Eliot Dean was getting his own back on his adversary.

‘If you’d like to give me a game of tennis tomorrow after breakfast, Quayle, I’ll show you who’s middle-aged and who isn’t,’ he said with a laugh.

‘You forget,’ said Hilary Carmody. ‘Tomorrow after breakfast we’ll be shooting your first scene with Dolores.’

‘Yes, but that’ll take ages to set up. You know how particular Joe the Sparks is with his lighting. Plenty of time for me to thrash young Quayle here in straight sets, and still be in time for my cue.’

‘Speaking of which,’ said Dolores La Mar, perhaps feeling that she had been out of the conversation long enough, ‘can I implore you, Eliot dear, not to come in with your line quite so quickly after, “If you want to know, I’ve come to get away … from everything.” There should be a pause there before you say, “Have you?” The line’s supposed to resonate.’

The pause which followed this remark was worthy of the West End stage-trained actor Eliot Dean had been before he’d turned to making films, thought Rowlands. ‘Isn’t that,’ said the actor at last, ‘rather up to Carmody to decide?’

‘Oh, leave me out of it,’ was the director’s cheerful reply. ‘But I don’t think we ought to be talking shop on our first evening, do you? Very tedious for Mr and Mrs Ashenhurst and their guests.’

‘Not at all,’ said Ashenhurst courteously. ‘As you may have gathered, we lead a rather quiet life here. Any change from that is very welcome, especially for the younger folk. Wouldn’t you say so, Danny?’

‘Rather,’ agreed his adopted son, with some enthusiasm. As well as having a fondness for motor cars, Daniel Ashenhurst was a devoted cineaste, with a predilection for cowboy films and adventure stories. If Eliot Dean was not exactly in the league of Tom Mix, he at least belonged to the same world as the one inhabited by that veteran of a hundred westerns. For that alone, Danny was prepared to give him the benefit of the doubt. But this reminder that the younger members of the party were still present was enough to call forth a summons from Edith to her youngest daughter that it was time to go to bed (‘But Mummy …’) and the same injunction from Dorothy to Victor, who looked half-asleep already, she said.

‘You’d better go, too, Danny,’ she added, to that gentleman’s mortification. ‘You know you’ve got to be up at six to feed the chickens. It’s almost ten o’clock.’

‘Goodness, what frightfully early hours one keeps in the country,’ drawled Laurence Quayle. ‘Why, in London one would only just be getting ready to go out.’

‘Then thank heaven we’re not in London,’ said Dean, getting to his feet. ‘I’m off for my walk. Coming, Liddy?’

‘All right.’

After this, the party began to break up – somewhat to Rowlands’ relief. One could have too much of a good thing, he thought, always supposing that the actors were a good thing. As Ashenhurst had said, it made a change from the quiet tenor of their life in Cornwall. The question was: having come here to escape London life, with all its noise and bustle, did he and his family really want such a change?

Next morning, Rowlands rose early, as was his custom during these summer months. Never a heavy sleeper, he usually found himself awake by the time the birds began to call, whether it was in his suburban street at home or, as now, beside the sea. The fact that they were gulls not sparrows made not the smallest bit of difference. Leaving Edith asleep, he made his way from their bedroom, in what was called the ‘old wing’, along the passage to the bathroom, which they shared with three other rooms. This part of the building – once a farmhouse – was sixteenth century, with the low ceilings and sloping floors common to that delightfully irregular architectural period. He was used to it by this time, but when he’d first started coming here, he’d taken a few headers down the stairs. Even now, he was careful to tread warily in case a loose board might trip him. Not so the young woman – for he guessed it was a woman – who came hurtling around the bend in the corridor, almost ending up in his arms. ‘Oh! Lo siento!’ she cried, revealing herself to be the Spanish maid. ‘Sorry … so sorry.’

‘Don’t mention it,’ he said. ‘I say, I hope you’re not hurt?’ but she had already turned and fled in the opposite direction. Evidently the sight of a strange Englishman in a dressing gown was too much for her, thought Rowlands wryly. After he’d washed and dressed, he descended the stairs to the hotel kitchen. Here he found Mrs Jago supervising her ‘girls’: ‘Now remember, Sal – she wants ’em soft-boiled … Morning, Mr Rowlands.’

He returned the greeting. ‘Is there a cup of tea to be had?’ he asked, guessing that this would have been the first thing to have been attended to, Mrs Jago sustaining herself throughout the day with cups of this refreshing beverage.

‘There is indeed, Mr Rowlands, sir. If you’ll sit yourself down, I’ll pour you one directly. Not out of that pot,’ she added darkly, evidently alluding to the smaller vessel, designed for one person, that was even now being placed onto the tray with the other breakfast things for Sally or Jenny to carry upstairs. ‘The tea in that pot’s as weak as water. Not but what it wasn’t asked for as such,’ said Mrs Jago, still in the same tone of dark foreboding. ‘Notions!’ she concluded, with a proper scorn for all such faddiness. ‘All right, Jenny, you can take’n up now, there’s a good girl. She said six o’clock and six o’clock it’ll be to the minute. Now then, Mr Rowlands,’ went on the cook, turning her attention to the more serious business of pouring out – this time from the large earthenware pot that stood at the centre of the table – ‘here’s your tea. And a good strong cup it is.’

Rowlands nodded his thanks and took a sip of the powerful brew. ‘Anyone else about?’

‘Just Master Danny. And didn’t he look pasty-faced this morning! Late nights,’ said Bessie Jago, in the tone of one who had seen the ruinous effects of these on many others, ‘don’t do a growing boy any good. I told’n, I said, “Master Danny,” I said, “you want to watch yourself, staying up till all hours …’’’

‘Well, at least he got up in time to feed the chickens,’ said Rowlands, to stem the flow. Recalling his own days of having to perform the same task, at the same early hour, made him grateful that those days were over. He’d never been cut out to be a chicken farmer.

‘There was that foreign woman, too,’ said Mrs Jago, setting down her teacup with a meaningful sniff. ‘Eye-talian, or some such.’

‘Spanish,’ said Rowlands. ‘You mean Miss La Mar’s maid, I suppose?’

‘Is that what she is? All I know is she came in here, quarter to six it was, wanting to know was the water really hot for Miss Whatsername’s bath.’ Another disdainful sniff. ‘Told her it wasn’t my job to see to the boiler. That’s Pengelly’s job, that is.’

‘I expect,’ said Rowlands, doing his best to soothe these ruffled feathers, ‘she didn’t know who else to ask.’

‘No doubt,’ was the reply. ‘All I can say is, Mr Rowlands, that we never had this kind of thing before. People asking for tea – plain boiled water, more like – and baths to be hot at six in the morning.’

‘Everything all right?’ said Cecily Nicholls, appearing in the doorway at that moment. ‘Ah, good. I can see you’ve got everything in hand, Mrs Jago.’

‘Yes, well … As I was saying to Mr Rowlands here …’

‘There’ll be five for early breakfast,’ went on Mrs Nicholls, cutting short this threatened outburst. ‘That’s poached egg on toast for Miss Brierley, and the rest of them bacon and eggs and all the trimmings, except for one lot of kippers – that’s for Mr Quayle. But I’m sure you’ve made a note of all that already, Mrs Jago.’

‘Yes’m.’

‘Good. Then it’s just the coffee at seven for Miss La Mar – and any of the others that want it. I said we could provide flasks, but so far only Mr Dean has taken me up on that.’

‘The tall gentleman – yes,’ said Mrs Jago, adding with a slight unbending of her manner, ‘Saw’n in Day of Reckoning. Ever so good, he was.’

‘Then that’s all settled,’ said Mrs Nicholls. ‘I knew I could rely on you. Breakfast at eight for everyone else, of course … If you can spare a moment, Fred,’ she went on when these arrangements had been dealt with, ‘there’s something on which I’d like your advice.’ She took his arm – managing to do this without making him feel he was being dragged along, as was sometimes the case with those well-meaning souls who imagined that being blind meant you’d lost the use of your other faculties – and the two of them went out onto the terrace at the back of the hotel. This was deserted at that hour, the sun having yet to move round to that quarter. ‘I thought you looked as if you needed rescuing,’ said Rowlands’ companion when they were out of earshot. ‘Bessie Jago is a treasure – we couldn’t manage without her – but she does run on sometimes.’

‘She obviously feels that Miss La Mar’s crowd have overstepped the mark as regards the behaviour proper to hotel guests,’ said Rowlands, with a smile.

‘Yes, although I can’t imagine why she should be getting so up in arms. We’ve had people down from London lots of times.’

‘But not film people.’

‘No, but we had that theatre crowd from the Minack two seasons ago, and she was as nice as pie about them. I really don’t know what’s got into her.’

Rowlands hesitated a moment. ‘Maybe,’ he said, ‘it’s the foreign element she objects to.’ He related Mrs Jago’s remarks about Dolores La Mar’s Spanish maid. ‘Some people are suspicious of foreigners, you know.’

‘I can’t have that,’ said Mrs Nicholls firmly. ‘It was bad enough just after the war, with some people not wanting to have anything to do with Germans. But at least there were reasons for that.’ She herself, she didn’t need to say, having had such a reason – the loss of her husband of two weeks to a German bullet. ‘I’d better speak to her, I suppose. Although the last thing I want is for her to give notice when we’re in the middle of our busiest time.’

‘I’d leave it a few days, if I were you,’ said Rowlands. ‘Things have a habit of settling down. Was there anything you wanted to ask me about?’ he added as they reached the end of the terrace and descended the steps that led to the lawn beneath. ‘Or were you just offering me an escape route?’

‘As a matter of fact, there was something.’ Cecily Nicholls was silent a moment as the two of them began to stroll along the path that led around the side of the hotel to the front drive. ‘It’s actually rather beastly. I haven’t said anything yet to Jack. He’s got a lot to deal with at the moment, and I didn’t want to worry him …’ Again she paused. Rowlands knew better than to press her. People generally said what was on their minds if you gave them the chance. ‘The fact is, there’s been a letter. It was addressed to Jack, as it happens, but naturally I open all his correspondence – at least,’ she corrected herself, ‘all his business correspondence. Anything that looks personal I leave to Dorothy, of course.’

Rowlands nodded his appreciation of this point, and she went on, ‘I’d assumed that this was just something of that kind – a business letter, or a circular. It was just a cheap envelope, with a single sheet of paper …’ She broke off.

‘What did it say?’ asked Rowlands.

‘It said: “Those who harbour traitors will die”, I thought it was a joke at first – some silly game the boys were playing. Traitors and death threats.’ Mrs Nicholls gave an uncertain laugh. ‘It sounds like something out of a bad film, doesn’t it?’ They had by now come round to the front of the hotel.

‘When did this letter arrive?’ asked Rowlands.

‘Yesterday. By the second post.’

‘Have you mentioned it to anyone else?’

‘No. That is … I asked Danny if he knew anything about it and he said no. He’s a truthful chap, as a rule, and so …’

‘I’m sure he had nothing to do with it,’ said Rowlands. ‘But I’m glad you told me.’

‘Yes, so am I. These things are rather nasty, aren’t they?’

‘Very. But try not to worry. When the moment’s right, I’ll have a word with Jack.’ Further conversation was cut short by the sound of the Rolls drawing up in front of the main entrance. Presumably this was to take Miss La Mar to the shoot, thought Rowlands. The driver got out, and began to polish the windscreen, to judge from the squeaking of chamois leather on glass.

‘Well,’ said Mrs Nicholls, ‘I’d better get on, I suppose. Are you coming in, Fred?’

‘I’ll take another turn around the garden before breakfast,’ he said. Although his real reason – he could not have said why – was to get acquainted with the only member of the film party he hadn’t yet met. ‘Fine morning,’ he accordingly said to the man, still busy with his polishing. The answer to this was a non-committal grunt. ‘You’re out and about nice and early,’ went on Rowlands, not deterred by this. Again, the reply was terse.

‘She wants it so. L’actriu.’ Rowlands guessed he meant Dolores La Mar, although the word – presumably ‘actress’ – he’d used was unfamiliar … some kind of dialect, perhaps?

‘Of course,’ he said; then, aware it was rather a clumsy change of subject, but not sure otherwise how to engage the attention of this taciturn type, ‘You’re from Spain, aren’t you?’

‘Catalunya.’

‘Lot of trouble in your part of the world recently.’

‘Trouble!’ The chauffeur gave a scornful laugh. ‘Sí, there has been much trouble, like you say. They will not rest, els feixistes, until they have killed us all.’ Again, the unfamiliar word – Rowlands guessed this must be Catalan. Los fascistas would have been the Spanish version. He was turning away with a polite murmur of commiseration when the man said, ‘Cigarette?’ thrusting the pack towards him.

‘Thanks.’ Although Rowlands would have preferred one of his own brand. But he interpreted this gesture as a sign that he had been accepted, if somewhat conditionally, by the other. As he bent his head to allow the chauffeur to light his gasper, trying not to cough as he inhaled the smoke from the rough-tasting tobacco, he reflected that it was hardly surprising if the fellow’s manner was a bit off-putting. Knowing that your country was in the process of being torn apart by fanatics would be enough to sour the temper of any man.

For the next few moments, they smoked their cigarettes in silence, the Catalan evidently being in no mood to enlarge upon his earlier remarks. And no wonder, thought Rowlands, if things were as bad as all that. Even though he tried to keep abreast of things as far as possible – listening to the news on the wireless and getting Edith to read the main stories aloud to him from the newspaper each day – it wasn’t easy to stay as up to the minute as he’d have liked. ‘When were you last in Catalonia?’ he asked.

‘Four months ago,’ was the reply. ‘I left just after Guernica … You know what happened there?’

‘Yes. Terrible business. One wouldn’t have thought even the Germans capable of such an atrocity.’

‘As you say, it was terrible. And it was the Francoists who were responsible, murderers that they are, even if it was the Luftwaffe who dropped the bombs.’ The chauffeur spat, suddenly, upon the ground. ‘After that,’ he said, ‘we knew it was impossible to stay. But Caterina – that is my sister, you understand – had heard of a job in London, working for l’actriu, and so we came here.’

‘Ah, that must have been your sister I met just now,’ said Rowlands, gesturing vaguely with his cigarette in the direction of the hotel. But the other made no reply, because at that moment the front door opened and Dolores La Mar came out, deep in conversation with someone. It was immediately apparent from the tone of this that all was not well, as far as the actress was concerned.

‘But darling,’ she was saying in a petulant voice as she descended the short flight of steps to the drive, ‘I really don’t see what the difficulty is … Surely you can make whatever changes to the script you like? You’re the director, aren’t you?’

‘I was, when I last looked,’ replied Hilary Carmody, for it was he. ‘All right, Casals’ – this to the chauffeur – ‘you can take us down to the village. The camera crew should have finished setting up by this time.’

‘Only I do feel that the sub-plot with the girl weakens the whole film,’ went on Miss La Mar as she made her leisurely way towards the Rolls, the passenger door of which was now being held open for her by Casals. ‘I mean, the audience isn’t going to be interested in the girl. She’s nothing but a minor character. It’s the love affair between Desirée and Edward they’ll be interested in.’

‘Darling, if we’re to get you into make-up, and ready for your first scene with Eliot, in time to take advantage of the morning light – which is what I particularly want for this scene – then we’re going to have to get a move on,’ said Carmody, good-humouredly. ‘I do see your point about Lydia’s character, but …’

‘I don’t see why she has to be in the picture at all,’ said the actress, getting into the car. ‘As for having Eliot – I mean Edward – fall in love with her, that’s patently absurd. Edward’s supposed to be in love with me – that is, Desirée. The audience won’t like it if he comes across as fickle.’

‘But darling, he only falls for Laura after Desirée’s death.’

‘And that’s another thing,’ said Dolores La Mar. ‘I mean, does she really have to die? It seems like such a miserable ending.’

‘That’s the story we’re working with, I’m afraid,’ said the director, going round to the other side of the vehicle and getting in beside her.

‘And as I said, the story can be changed,’ was the retort. Casals shut the door on this remark, and any further conversation was cut off from Rowlands’ hearing. Casals got into the driver’s seat and a moment later, there came the sound of the Rolls driving away. At once, Rowlands dropped the remnant of his acrid-tasting smoke on the gravel and ground it out with his heel. Time for breakfast, he thought. He’d better go and see if Edith and the girls were down.