7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

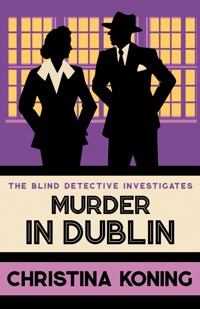

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Blind Detective

- Sprache: Englisch

'With vivid characterisation and a keen ear for dialogue, Christina Koning has all the qualities of a first-class mystery writer' - DAILY MAIL Dublin, 1939. As the Second World War looms ever closer, blind war veteran Frederick Rowlands travels to the neutral territory of Ireland at the behest of Celia Swift, whose husband, Lord Castleford, has been receiving mysterious death threats. When a body is discovered, Castleford finds himself being accused of a murder he did not commit. As Castleford's trial begins, Rowlands must fight to save his friend's reputation - and his neck from the gallows. As a country teeters on the knife-edge of war and a man's life hangs in the balance, will the Blind Detective identify the true killer in time?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 450

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

3

MURDER IN DUBLIN

CHRISTINA KONING

For Eamonn

Contents

Chapter One

It was getting on for ten o’clock at night when the Liverpool ferry docked at North Wall Quay after what had been as smooth a crossing of the Irish Sea as one could have hoped to enjoy, thought Frederick Rowlands. It was of course high summer, he reminded himself as he lit a cigarette; he supposed it might be a very different story in the depths of winter when storms would make the crossing a far less pleasant experience.

Standing by the ship’s rail, he savoured the first few moments of arrival in a strange city as around him the business of disembarking passengers and unloading cargo began. ‘I always think this is the best way to approach Dublin,’ said his companion, who was standing next to him, close enough so that he could catch the scent of her hair, and the perfumed smoke of the Turkish cigarettes she favoured. ‘With the lights of the buildings along the waterfront shining on the river, and the loafers on the quayside, and the feeling one has – here, more than in London, I feel – of having arrived in the heart of things … although I imagine,’ she added, as if it had just occurred to her, ‘it isn’t the same for you.’

‘Not exactly the same,’ he replied, offering her his arm as the two of them started to move towards the gangplank, across which groups of foot passengers were already making their way. ‘But I can picture it, from what you’ve said. The lights and the buildings. The loafers, too – one finds them in every port. Then there’s the smell of the place – or rather, that of the warehouses along this stretch of the river. Coffee, and pepper, and beer – there must be a brewery nearby. And the sounds of the voices. Is that Irish they’re talking, those fellows?’ She said that it was. ‘I knew it was a language I hadn’t heard before although heaven knows I met enough Irishmen during the war …’ But she was only half-listening.

‘Now, where’s O’Driscoll got to?’ she murmured, looking out for the servant who was to meet them. ‘He should be here. I wired before we left Liverpool.’

They had, by this time, reached the quayside where a crowd of those meeting the ferry jostled against those who were getting off; there seemed to be no particular organisation. ‘Perhaps,’ said Rowlands, feeling himself pushed this way and that, and doing his best to protect his companion from the same, ‘we should find a quieter spot to wait until this crush clears?’

But just then there came the clatter of hurrying footsteps along the cobblestones. ‘Milady! Oh, milady! I was afeared I’d come too late and missed you.’

‘You certainly might have been earlier,’ said his mistress. ‘But no matter. Where have you left the car?’

‘Over the way, milady. Was it a good journey, now?’

‘Not bad.’

‘And the sea as calm as a millpond,’ said the man, sounding as satisfied as if he’d arranged this himself. ‘Would there be any luggage, milady?’

‘Yes. There are my two bags and one of Mr Rowlands’. See to it, will you? And then let’s waste no more time. We’ve had a long journey.’

‘To be sure,’ was the reply. ‘Patsy’s after collecting the luggage now. Hi there, Patsy! Over here with the bags, now! Car’s this way, milady. Just a few steps,’ added O’Driscoll in an encouraging tone. Within a few minutes, the travellers were seated in the back of the Bentley, with O’Driscoll taking his seat next to the silent Patsy, whose functions evidently included that of chauffeur. ‘Merrion Square, is it, milady?’ enquired the former. Being assured that it was, he conveyed this fact to the latter. Then they were moving, at a steady but not excessive speed, along the river – ‘The Liffey,’ murmured the woman beside him to Rowlands – and across O’Connell Bridge. Trinity College soon appeared on their left, so Rowlands’ companion told him, after which it was more or less a straight line to their destination where they arrived in little more than ten minutes.

‘Here we are,’ she said as they drew up in front of a house about halfway along the far side of the square. As he got out of the car, Rowlands had a sense of a freshness in the air that came from the presence of trees, and of a fountain playing softly somewhere. There was something else – the quiet that hung about the wealthier parts of cities where the raucous sounds of the poorer streets seldom, if ever, penetrated.

Rowlands followed the mistress of the house up a short flight of steps, to a door that already stood open. A sensation of warmth and light met him as he entered the spacious hall. A smell of fresh flowers and polished wood, with a faint, underlying scent of something else – fine cigars, he thought, wondering if he was shortly to meet the man whose indulgence they were. Invisible hands, like those in one of the fairy tales his girls had once loved, divested him of his coat. ‘Baths first, I think, don’t you?’ said his hostess, preceding him up the stairs. ‘And then we’ll see what Mrs Keane has left for us. You needn’t dress,’ she added. ‘Half an hour, shall we say? John will show you to your room.’

Left to his own devices in the room to which he had been conducted by the servant, Rowlands took a few moments to familiarise himself with its layout, something which had, of necessity, become habitual in the more than twenty years since he had been blinded by an exploding shell at Passchendaele. Having first ascertained the position of bed and fireplace (in which a fire had been lit against the evening chill), and finding that his suitcase had already been brought up, he undressed, and having put on his dressing gown, took his sponge bag and found his way across the corridor to the bathroom that served this end of the house. Here, a bath had already been drawn; he got into it gratefully, finding the water as hot as he could have wished.

It had been almost twelve hours since he had met, at Euston station, the woman at whose behest he was here. As he let the tensions of the day slip away, in the warmth of the pleasantly scented water, he reflected on what had led up to that meeting, and why it was that she had sought him out after so long.

Two days ago, if you’d mentioned her name to him, it would have conjured memories already almost a decade old: memories of a dangerous sweetness that threatened his carefully maintained peace of mind. He’d had news of her over the years, of course. A woman who occupied the place she did in society, and who, moreover, had been briefly notorious, couldn’t expect to disappear entirely from public awareness although her marriage six years before, to an Irish peer, had seemed to guarantee her removal from the epicentre of London society. There’d been nothing in these occasional snippets of information, concerning her appearance at a Dublin ball, or a race meeting, perhaps, that might have pointed to her sudden reappearance in Rowlands’ life.

He’d stayed at work later than usual on that particular evening because, with Edith and the girls away in Cornwall at the start of the summer holidays, and Edith’s mother seen off that morning on the train to visit friends in Scotland, there was no special reason to hurry home. Miss Collins had already left, taking the letters for posting with her, and Rowlands was making notes in his careful script – guiding his hand by means of a ruler so as to avoid going off the page – to remind him what needed to be addressed with his secretary the next day. Absorbed in this task, he wasn’t aware that anyone had come into his office until the intruder spoke: ‘I hope I’m not disturbing you? I asked at the house and they said you hadn’t yet left.’

For a moment, Rowlands found himself unable to utter a word. Was it really her – or was this merely a soft-voiced hallucination, come out of the past to torment him? ‘Lady Celia,’ he managed at last. ‘I …’

‘You don’t seem awfully glad to see me, Mr Rowlands.’

‘I’m just surprised, that’s all. It must be seven years …’

‘Eight,’ she said. ‘Almost to the day. It was at that party in Richmond where the girl was attacked. Awful business. I drove you home after the police had finished with us, didn’t I?’

‘You did,’ said Rowlands, for whom every detail of that night was etched in memory. ‘And I am glad to see you,’ he added. The obvious question, which was what it was that had brought her there, hung in the air between them. But if she sensed this, Celia Swift evidently wasn’t in any hurry to answer it. ‘So this is where you work?’ she said. ‘Rather nice to be right in the middle of Regent’s Park.’ For this indeed was where the St Dunstan’s HQ was located. ‘It took me quite a while to track you down. I had to ask at the other place – Gerald’s old office, you know.’

‘Yes.’ The mention of his late CO, Gerald Willoughby, briefly transported Rowlands back to his former place of work where he’d been for seven years until disaster intervened, a disaster in which Lady Celia (Celia West, as she was then) had been intimately involved. ‘I came there once, if you recall.’ He did, all too vividly. Because it had been then that he’d come to realise the power she had over him. It was a power she was exercising at that moment as she moved about the room. It had to do with her voice, her scent – musky, exotic – with the languor of her movements, the rustle of her silk dress. One might have called it seductive, except that it seemed artless.

Pausing for a moment in her restless wandering, she fiddled with the objects upon his desk: a paperknife; a painted jar that one of his girls had made, containing pencils; a wave-smoothed stone, picked up on Brighton beach. ‘I was hoping,’ she said at last, ‘that you’d have dinner with me.’ She was staying at the Savoy: ‘We can get a bite to eat in the Grill,’ she said. ‘Then we needn’t dress.’ It was all the same to Rowlands, although he rather wished he’d been wearing his best suit instead of the one he wore to the office; he reminded himself that while he was in Celia Swift’s company, no one would be looking at him anyway.

In the taxi on the way from Regent’s Park, their conversation had necessarily been confined to pleasantries. She enquired after the health of his wife and family; he reciprocated by hoping that she herself was well. ‘Never better,’ she replied with an airiness that made him think she wasn’t being entirely frank. Then, changing the subject: ‘I remember your daughters. Dear little things! I’ve a boy of my own now, you know.’

He hadn’t known, and said that that was good to hear. ‘Yes, he’s quite a jolly little chap. Just turned five. Ned – that’s my husband – is keen to start him off with his first pony, but I think he’s too young.’ A brief silence ensued.

‘I haven’t seen you since your marriage,’ said Rowlands, deciding to follow up on this conversational opportunity. ‘It must be very different, living in Ireland … I mean after London.’

‘Oh, it is. Although I’ve only just begun to realise how different.’

Before he could discover what, if anything, she meant by this cryptic remark, they arrived at the hotel. Greeted by the manager in that fashionable establishment’s lofty entrance lobby, they were conducted by another factotum to the restaurant. From the subdued murmur of conversation that met them as they walked in, Rowlands judged that the place was far from full. It was still early, of course. A waiter led them to a table on the far side. ‘I believe the steaks are good here,’ said Lady Celia as they were seated. Rowlands said that, in that case, he’d have the steak. ‘We’ll have a bottle of Burgundy to go with it,’ said his hostess to the waiter. ‘And I’ll have the fish.’ She waited until the man had brought the wine, poured it, and left them to their own devices before she spoke again. ‘Tell me … how’s your sister?’ Rowlands, who’d been wondering for the past hour what her reason was for inviting him here since he assumed it couldn’t simply be for the pleasure of his company, was nonetheless taken aback. ‘My sister?’ he echoed, recalling the circumstances under which the two women had last met – circumstances no doubt highly uncomfortable to both. ‘She was very well when I last saw her. She … she married again, you know. Seems very happy.’

‘I’m glad,’ said Lady Celia. She took a sip of wine and set down her glass. ‘And the child? I forget his name …’

Rowlands had the feeling this wasn’t true. ‘William,’ he said. ‘Known as Billy. He’s not such a child any more. He’s seventeen.’

‘I suppose he must be,’ she said drily. ‘You know there was money left to the boy … in my late husband’s will?’ She seemed reluctant to mention him by name.

‘Yes,’ said Rowlands. ‘I believe I did hear something about that.’ Was this why she’d sought him out? ‘But I don’t think she – my sister – cares about the money,’ he added, wanting to disabuse her of the idea that he, or his sibling, might harbour such mercenary designs.

‘Perhaps not. But I do,’ replied Celia Swift impatiently. ‘That is … I don’t care about it. I don’t want it. It’s his. The boy’s.’

‘Lady Celia—’

‘I’ve been to see my solicitors,’ she said, cutting across him. ‘It’s one of the reasons I came to London. Ned, my husband, agrees with my decision. He says it’s my money, to do with as I please. I’ve put it in trust for the boy … for William,’ she said. ‘He’ll get it when he’s of age.’

Somewhat stunned by this information, Rowlands did not at once reply. ‘What about your own boy?’ he wanted to say, but did not.

She must have read his thought, however, for she said, ‘I don’t need, or want, his money.’ Rowlands knew it was her late husband, Leo West, of whom she spoke. He thought he understood the reason for this. After the shocking events that had ended her marriage to the wealthy entrepreneur, she would doubtless regard the money as tainted.

Their food arrived, and for the next few minutes they occupied themselves with the agreeable business of consuming it, or rather, Rowlands did. Lady Celia merely pushed her food around her plate. He remembered her figure as slim and girlish; he guessed she hadn’t changed in that respect. She would have kept the same graceful form he had once, briefly, held in his arms, just as the same delicious scent – a heady mixture of expensive perfume and Turkish cigarettes – clung to her skin and hair. What was different was a new hardness in her voice. She pushed her plate away, and lit a cigarette. ‘That wasn’t the reason I wanted to see you,’ she said. ‘Or not the only reason.’

He hadn’t finished eating, but he put down his knife and fork, and waited to hear what she had to say.

‘That was the reason I gave him – Ned, I mean – for my coming to London. Setting up the trust, and some other business I had to see to. The sale of some property …’ She broke off as if the subject bored her. ‘No, it was something else I wanted to ask you about,’ she was saying. ‘The truth is, I need your help, Mr Rowlands … or may I call you Frederick? You helped me once before when no one else did.’

Rowlands waited. His companion seemed to be nerving herself for what she had to say. Even so, it was a shock when it came: ‘I think someone’s trying to kill my husband,’ she said. ‘In fact, I’m sure of it. You must help me prevent it.’

There had been letters, she said: vaguely threatening in tone at first, latterly of increasingly violent language.

‘Have you kept them?’

‘Only the most recent ones. Ned threw the first couple in the fire.’

‘Can you give me an idea of what they said?’

‘Well …’ She lit another cigarette. ‘Shall we have our coffee in the lounge? We can be more private there.’ When they were settled in a corner of this vast apartment, whose atmosphere of hushed opulence was made more so by the luxurious thickness of the carpet, Lady Celia resumed her tale, which sounded all the more luridly fantastical by contrast with these civilised surroundings. ‘To begin with, as I said, the letters contained vague threats. “We know how to deal with your kind.” “Go home, English scum.” That kind of muck. Then they got more specific. “You’ll be sorry you ever set foot in Castletown and your English whore with you …” I don’t think,’ she added wryly, ‘that they approve of me, either.’

‘Who are they? Do you have any idea?’

‘Ned thinks they’re IRA malcontents, or they could just as well be Blueshirts. That’s the Protestant lot,’ she explained. ‘They’re all as mad as each other. The one thing on which they agree is that they hate the English. Unfortunately for Ned, he’s only a quarter Irish, on his mother’s side, and I haven’t a drop of Celtic blood.’

‘But …’ Rowlands refused her offer of a Turkish cigarette, preferring his own. ‘Why now?’ he said when it was lit.

‘Haven’t you heard?’ was the faintly mocking reply. ‘There’s going to be a war. And Ireland’s keeping out of it if de Valera has his way. Ned says it’s a golden opportunity for them to rid themselves of the enemy.’

‘The enemy?’

‘Us. The British.’

‘And you believe these letters are part of a campaign to force you and your husband out?’ said Rowlands.

‘I do,’ she said. ‘It’s not just letters, either. One might ignore those, although it’s not very pleasant to know one’s hated. But it was when they killed Ned’s favourite dog that I really started to worry. Oh yes,’ she said, seeing his horrified expression. ‘Shot the poor beast in cold blood and left him for Ned to find. He says it was probably an accident – some farmer letting loose at what he thought was a stray – but I don’t believe it. Especially not when another letter came the next day. “You’ll be next, my lord,” it said. If that isn’t a death threat, I don’t know what is.’

‘Have you informed the police?’ said Rowlands. ‘Surely they—’

‘The Gardai are as mixed up in politics as all the rest,’ said Celia Swift crisply. ‘Ned did talk to the local man, Sergeant Flanagan, who said he’d look into it, but I don’t imagine he’ll exert himself overmuch. To be blunt, Frederick, they want us gone. We’re the oppressors, in their view. The sooner we, the English, get out of Ireland, the better, in their estimation.’

Rowlands was silent a moment, reflecting on what she had said. ‘I still don’t see how I can be of help,’ he said, at last. ‘I’ve never set foot in Ireland … and my knowledge of its politics is shaky, to say the least.’

‘I’ve come to you because you stood up for me, all those years ago,’ she said. ‘You saved me from the gallows. Now I want you to save my husband from being murdered. Please, Frederick. You’re my only hope.’

Having bathed and changed his shirt, Rowlands made his way back to the entrance hall where the obliging John was waiting to conduct him to the library. Here he found Lady Celia seated in front of a good fire. ‘There’s a chair directly opposite mine,’ she said. ‘And there are sandwiches and coffee … unless you’d prefer a whiskey?’

‘Coffee’s fine.’

She poured them each a cup. ‘Black or white?’

‘Black, please.’

She placed the cup on a low table at his side, and handed him a plate of sandwiches. ‘Mrs K’s made enough to feed an army. I hope you’re hungry.’

He was, as it happened. It seemed a long time since they’d lunched on the train to Liverpool. The sandwiches were ham, and very good. He had eaten two before his hunger abated. Celia Swift seemed content to watch him eat while she sipped her coffee and smoked a cigarette. ‘I’m so glad you agreed to come,’ she said. ‘It makes me feel so much safer to have you here.’ Although what good his being there would do was debatable, thought Rowlands. A blind man, with little knowledge of the country in which he had just arrived.

‘I don’t know what you expect me to achieve that the police can’t,’ he said. He pushed away his plate, and lit a cigarette. ‘And …’ He hesitated.

At once she picked him up. ‘What?’

‘Just that … I don’t imagine your husband will take kindly to having a man he’s never met interfere in his business,’ he said. ‘I mean, surely he must have his own ideas about all this?’

‘Oh, Ned just dismisses it as some kind of nasty prank,’ she replied. ‘As for what he’ll think of you,’ she went on. ‘He’ll think what I’ve told him to think, which is that you’re an old friend I happened to run into in London and that you’ve had considerable experience of this kind of thing.’

‘You told him that?’

‘Don’t look so alarmed. It’s true, isn’t it?’

‘Well …’

‘Ned’s much more likely to listen to you than he is to take notice of what a mere wife might say,’ said Celia Swift. ‘I want you to convince him to take these threats seriously, that’s all.’

Rowlands doubted whether anything he could say would make the slightest difference, but he held his peace. He was here now, wasn’t he? He might as well go along with what she’d proposed. ‘Will we see Lord Castleford tonight?’ he asked.

The answer was in the negative. ‘He’s at the estate. We’ll see him tomorrow with all the rest of the crew. I’d better put you in the picture about Ned’s family,’ said Lady Celia.

Edward Swift was the younger son of an earl. His elder brother, John, had been killed at the Somme, and so the title had passed to Edward, on the death of his father. The latter had been married twice – the boys’ mother having died when Edward was an infant – and there was another son, Jolyon, by the second marriage, to Eveline, the much younger daughter of a local landowner. ‘I wonder what you’ll make of our dear Eveline?’ said her daughter-in-law, with a faintly satirical edge to her voice. The Dowager Lady Castleford had been given a home by her stepson, to which, naturally enough, her own son was frequently invited. ‘Jolyon lives with us most of the time,’ said Lady Celia. ‘At least … it feels as if he does, he’s about the place so often, with that wife of his.’ The couple had a young son, Reginald. ‘He’s two years younger than our boy, and so he’s not much company for him. Besides which …’ She left whatever comment she’d been about to make unsaid.

In addition to these people, she went on, there was ‘Cousin Aloysius, a retired canon. I’m not sure what relation he is to Ned exactly, but he’s a dear old boy. The best of the lot, in my opinion. You’ll also meet Robert Butler – he runs the estate – and his wife, Elspeth. She’s rather a starchy sort, but she means well. And there’s Sebastian Gogarty, who’s been cataloguing the Castleford library for the past few weeks. Now,’ she said as if the subject held no more interest for her, ‘I want to hear all about your girls,’ which was no hardship to Rowlands, whose three daughters were the delight of his life.

And so he told her about Margaret, midway through her studies in mathematics at Cambridge; and about Anne, who was currently torn between following her sister to St Gertrude’s College, or pursuing a career in fine art; and finally about Joan, the youngest, whose preoccupations at present were those of any healthy schoolgirl: hockey, the games mistress, and getting enough to eat. ‘You never saw such an appetite!’ said her father fondly. ‘I think she’ll end up being the tallest of the three.’

Chapter Two

They set off for Castleford after a leisurely breakfast; the journey would take no more than an hour if they went at a comfortable pace, said Lady Celia. They’d take the road that passed through Dundrum. ‘It’s quite a pretty little place although Enniskerry beats it by a mile – or so we think,’ she said, meaning herself and her spouse, Rowlands supposed. ‘Of course, we can’t compete with Powerscourt. That’s frightfully grand, you know. We prefer our place even if it is a bit of a barracks. All the houses of that era are. But we like it. It’s a working farm too, you know.’ Rowlands said he was glad to hear it. ‘Oh yes,’ went on this surprising convert to the joys of the rural life. ‘We produce all our own butter and eggs. And we’ve one of the best flocks of Blackface sheep in the county. Prizes at all the local fairs.’

As she chattered on, it struck Rowlands that her enthusiasm cloaked a deeper anxiety. It was as if she were trying to convince him, and herself, that she had made the right choice in abandoning the whirl of London life for the seclusion of the Irish countryside. Although, as the powerful car rolled smoothly along through the verdant scenery of County Wicklow, ‘it really is greener here. I thought it was a myth before I came’ … he wondered what choice she had had. A series of unfulfilling affairs with dubious playboys (he’d met one or two of them); living off the interest from the money her (detested) husband had left her; the vague notoriety of belonging to the fast set: an ageing beauty, with no one to care whether she lived or died. Except that one man had cared – too much for his own good. At the thought of his late employer and friend Gerald Willoughby driven half-mad by a hopeless passion for the beautiful Celia West, Rowlands shook his head to dispel the memory. As for his own sad case …

‘What did your wife say when you told her you were coming to Ireland?’ said Lady Celia as if she’d guessed the way his thoughts were tending.

‘I told her I’d got some business to see to, and that I’d join her and the girls in Cornwall next week,’ he replied, not quite answering the question.

‘Well, I’m grateful to her for sparing you,’ she said. ‘If you could just convince my husband to take this matter seriously, I’d feel that our “business” had been concluded successfully.’

‘But … Lady Celia … I still don’t understand. Why should Lord Castleford pay attention to anything I might say? He doesn’t know me from Adam.’

‘He knows you saved my life once,’ she said in a low voice, although the glass screen separating those sitting in the back of the car from the driver’s compartment was closed. ‘That’ll be good enough for him. And the fact that you’re a detective—’

‘I’m not a detective.’

‘—who’s worked with the police on numerous occasions,’ she went on, ignoring his protest. ‘Ah, here’s the lodge, and Nancy coming out to open the gate for us.’

Rowlands surmised that this must be the lodge-keeper’s child, for as the Bentley slowed down to a crawl, and began to move through the open gates, Celia Swift wound down the near-side window, and spoke to the child. ‘Here’s sixpence for you, Nancy.’ To which the little girl gave some reply unintelligible to Rowlands, but which seemed to satisfy his companion, for she laughed. ‘Droll little thing! She always looks at me as if I were going to bite her. Maybe I will, one day. Her cheeks are so very round and red.’ Settling back into her seat, she went on: ‘The approach to Castleford is really very pretty. Would you like me to describe it?’

‘Please,’ he said.

‘All right. In the distance you can see the Wicklow Mountains – they’re famous, you know. On a day like this, you can see for miles across the valley. Of course,’ she added, ‘the same can’t be said when it’s raining … which it does rather a lot, in Ireland. There’s a river at the bottom of the valley – hence Castleford. That part of the demesne is quite wooded … and the park itself has some fine oak trees. An avenue of lime trees leads to the house, which is set on rising ground. It was built by Ned’s great-grandfather, and is in the Palladian style, if you know what that is?’

Rowlands said that he did.

‘That’s more than I knew before I came here.’ She laughed. ‘But then I’m ignorant about lots of things. My father believed that educating girls was a waste of money. The house is rather a good example of its kind,’ she went on, like a dutiful child reciting a lesson. ‘It’s built of Wicklow granite, faced in ashlar. Rather grey and austere until one gets used to it. There are two symmetrical wings on either side of a central pedimented section. It’s called a breakfront,’ she added. ‘Each wing has three sash windows on each floor – there are two floors – except in the breakfront, which has three floors, with three windows on the second and third floor, and two arched windows on the ground floor. There are steps leading up to the front door, and pillars on either side of it, going up to the roof of the pediment, which is triangular, like a Greek temple, or so Ned says. There! I’ve told you all I can about the outside. You’ll have to wait to hear about the rest.’

Rowlands said he looked forward to that.

The car drew up on a gravel sweep in front of the house, to a chorus of barking dogs. ‘The reception committee,’ said Celia Swift as they got out. ‘Down, Juno! Down, Jess! Down, Jason! They’re quite well-behaved as a rule,’ she added apologetically to Rowlands, who found himself the centre of attention from the beasts, one of which, he guessed – from its size and shaggy coat – to be an Irish wolfhound. Lady Celia confirmed this supposition. ‘That’s Jason. The brother of Jasper – the one that was shot. He still misses him, poor beast … Ah, here’s Ned,’ she cried as the master of the house appeared at the top of the steps. ‘Darling, I want you to meet Frederick Rowlands, one of my oldest friends.’

More than a little startled at this description of himself, Rowlands held out his hand. ‘How do you do, my lord?’

‘Ned Swift. No need for the handle,’ was the reply as they shook hands. From this brief contact, Rowlands got an impression of a strongly built man, of around his own age and height. His hand, though well-shaped, had the slightly roughened texture of a hand used to outdoor work. ‘Good to meet you. My wife’s spoken about you quite a bit.’

This was even more startling. ‘Has she?’

‘Indeed she has.’ There wasn’t a trace of an Irish accent, which was hardly surprising, thought Rowlands, given that, from all Lady Celia had told him, the family was of English origin. ‘Come in, why don’t you?’ Lady Celia linked her arm companionably through Rowlands’ as they mounted the steps, and crossed a broad stone terrace before passing through the open door into a lofty entrance hall. Rowlands’ impression was of warmth and light – no doubt an effect of the sunshine that streamed in through the door, and the two tall arched windows, of which his hostess had spoken.

‘We’re very proud of the floor in this room,’ she said. ‘It’s Irish oak.’ Which would explain the absence of the usual chill to be found in houses of the grander sort, whose halls were floored with marble, thought Rowlands. ‘It was installed in 1824 when the family were expecting a visit from George IV. He was staying at Powerscourt – that’s our grand neighbour, you know. But he didn’t turn up.’

‘Too busy enjoying himself with his mistress, the dirty dog,’ put in Swift.

‘The decorations are … what do you call it, Ned? Greek Revival? That’s it. There are fluted Ionic columns on either side of the door that leads to the main staircase and—’

‘I’m sure your guest doesn’t want to hear all this stuff, Celia,’ interrupted her spouse.

‘Sorry! I was only trying to give him a picture.’

‘Actually,’ said Rowlands. ‘I was enjoying it very much. Lady Celia might not have mentioned the fact that I’m blind. So I’m grateful for any description of my surroundings even if it might strike others as odd to hear them described.’

‘In which case, I’ll say nothing more,’ said Swift, opening a door. ‘Carry on with your tour, Celia.’

But his wife said she felt too self-conscious to continue. ‘Although the morning room is one of the best rooms in the house,’ she said. ‘It used to be the music room, and so the mouldings on the ceiling are all of harps and flutes and violins. It gets the morning sun, so we often sit here before lunch if we’ve nothing better to do. Do take a seat, Frederick. There’s a sofa straight ahead of you, in the sunny spot by the window.’ She must have touched a bell, because a moment later the door opened.

‘Yes’m?’

‘We’ll have our coffee in here, Mary.’

‘So you were in the war?’ said Swift, throwing himself into a seat adjacent to Rowlands’.

‘Yes. Royal Field Artillery.’

‘I was in the Irish Guards. You were at the Somme, I suppose?’

‘That, and Ypres,’ replied Rowlands. ‘It’s where I got my Blighty one.’

‘Bad show,’ said Swift.

‘It was – for a lot of people,’ agreed his guest. ‘I made it home.’

‘If you’re going to talk about the war, I’m leaving you to it,’ protested Lady Celia. ‘Since I’m not allowed to describe the room, I don’t see why you men should swap war stories.’

‘You’re quite right, my dear,’ said her husband. ‘We’ll leave it until after dinner. Do you ride, Rowlands?’

The sudden change of topic was disconcerting. ‘I have ridden,’ admitted Rowlands after a moment. ‘When I was a boy, on my great-uncle’s farm in Norfolk. But not since.’

‘I thought, as you were in the war …’

‘I was a gunner,’ said Rowlands. ‘The only horses I and the other men in my battery had to deal with were the poor broken-down beasts that drew the limbers.’ It was generally the officers who rode, he recalled, but did not say.

‘To be sure,’ said Swift as if he’d suddenly remembered this, too. ‘But if, as you say, you used to ride as a lad, you’ll find it comes back to you – wouldn’t you say, Celia?’

‘Oh, don’t drag me into it!’ she said. ‘As you’ll have gathered, Frederick, my husband doesn’t consider a day well spent unless he’s ridden ten, or preferably twenty, miles. Put it on the table, would you, Mary?’ she added to the parlourmaid, who had just returned with the tray. She busied herself with pouring out as her husband pursued his theme.

‘The fact is, one never forgets how to ride. It’s instinctive. Put you on a quiet animal, with a companion to ride alongside you, and you’ll be fine,’ he said to Rowlands, who was beginning to realise that, for Swift, the subject was indeed a passion.

‘Your coffee cup’s on the low table in front of you,’ said Lady Celia. ‘And there are some of Mrs Malone’s ginger biscuits.’

‘If you’d care to, we can walk over to the stables before lunch, and I’ll show you the horse I’ve got in mind for you,’ Swift went on, picking up his own cup, and stirring sugar into the coffee.

‘I’d like that,’ replied Rowlands, thinking it best to go along with his host’s obsession. He could always find some excuse later.

At that moment, the door opened, and somebody stuck his head in. ‘Aha!’ said a voice. ‘I thought I smelt coffee! Hello, Celia. So you’re back, are you?’

‘As you can see,’ she replied. It seemed to Rowlands that there was a distinct coolness in her tone.

‘And who are you?’ said the newcomer, evidently addressing Rowlands.

The latter was about to supply his name when Swift intervened: ‘Sorry. Ought to have introduced you. This is my brother, Jolyon Swift.’

‘Half-brother, if we’re being precise,’ said the other, pouring himself a cup of coffee.

‘Half-brother, then. Jo, this is Frederick Rowlands, a friend of Celia’s.’

‘Oh, so you’re the man, are you? Celia’s been very secretive about you! All we knew was that she’d picked you up on her London jaunt. Positively mysterious, we all thought, didn’t we, Neddie?’

‘Leave me out of it, will you, Jo?’ said Swift, with an edge of impatience. ‘And cut the fooling. You’re making our guest feel uncomfortable.’

‘Not at all,’ said Rowlands. ‘And there’s no mystery about it. Lady Celia and I had a mutual friend, at one time. He was my commanding officer during the war. After his death, we – Lady Celia and I – kept in touch, that’s all. When she was last in London she was kind enough to look me up.’

‘Oh,’ said Jolyon Swift flatly as if he’d suddenly lost interest in the topic. ‘This coffee’s cold. Can’t stand cold coffee. Ring for some more, would you, old girl?’ It struck Rowlands that any man who could bring himself to address the exquisite Celia Swift as ‘old girl’ was either being very stupid or deliberately provocative. He suspected the latter.

Her Ladyship evidently thought so, too, for she said languidly, ‘Don’t be a bore, Jolyon. The bell’s there. Ring it yourself.’

‘I assumed,’ he replied, ‘that you’d prefer to give the order yourself since you’ve asked us – Henry and me – not to “give extra work to the servants”, as you put it. But heigh-ho, it shall be as you wish.’

He must have pressed the bell, for after a brief interval, the door opened again. ‘Yes’m?’

‘Bring Mr Swift some coffee, will you, Mary?’ said Lady Celia. ‘Will Henry want some, do you think?’ she added to her brother-in-law.

‘No idea,’ was the reply. ‘Haven’t seen her all morning.’ From which Rowlands gathered that the person referred to was female. This proved to be the case a moment later when a young woman, accompanied by a small child, entered.

‘There you are!’ she exclaimed ill-temperedly. ‘I’ve been looking for you all over.’

‘Well, you’ve found me, my angel,’ said Jolyon Swift. ‘We were just debating whether or not you’d like some coffee, and here you are, to clarify the matter.’

‘Oh, don’t be such an ass! Of course I want some.’

‘Bring some coffee for Mr and Mrs Swift,’ said Lady Celia to the maid, who disappeared on this errand.

‘And you’ve brought Reggie with you – what joy!’ cried the irrepressible Jolyon. ‘Henry, I must introduce you. This is Mr Rowlands, Celia’s Man of Mystery. And this, Rowlands, is my adored wife, Henrietta, and the son and heir of my heart, Reginald Castleford Swift.’

‘Delighted,’ said Rowlands, wondering why the honeyed words should have left such a sour aftertaste. At the mention of his name, the child, whom Rowlands guessed to be about two or three years old, set up a whining noise, of which the only distinguishable words were ‘Mama’ and ‘bikkie’.

‘Don’t pester,’ said his mother wearily. ‘You know Nurse said not before lunch. He wants a biscuit,’ she added superfluously. When the chant of ‘bikkie, bikkie’ grew more insistent, Mrs Swift relented: ‘All right. Just one.’ With which the child, seizing his booty, ran triumphantly from the room, to general relief, Rowlands suspected.

‘You spoil him, Henry,’ said her husband, taking a biscuit from the plate and biting into it. ‘If he goes on like this, he’ll turn into a greedy, selfish little beast.’

‘Like his father,’ was the tart retort. From which Rowlands deduced that the Jolyon Swifts were the sort of couple who enjoyed sparring in public.

Ned Swift evidently decided he’d had enough, for he got to his feet. ‘I’m off to the stables,’ he said. ‘Coming, Rowlands? I can show you the mare I’ve got in mind for you.’ Rowlands readily agreed, although privately he was dubious about the idea of getting on a horse again after so long. Even if he managed the first part successfully, he wouldn’t be able to see where he was going, so what would be the point? But it would be good to get out in the fresh air, on such a glorious day, and besides, against his expectations, he was starting to warm to Swift. ‘Are you coming too?’ said the latter to his wife, who replied that they should go on ahead, as she had things to see to. The dogs had been waiting patiently in their baskets for just such an eventuality; they now rose as one and followed the two men out.

‘Ever been to Ireland before?’ said Swift as they crossed the hall, and passed through a door to one side of the staircase (a double sweep, Rowlands was later to discover). Rowlands said that he had not. ‘Hmm. You’ll find it quite a change from London. The people are good-hearted. But it can take a while for an outsider to be accepted.’ It was more or less what Lady Celia had said. Rowlands, who had no expectation of staying long enough to be ‘accepted’, gave a non-committal grunt. A corridor led to the back of the house, past kitchen and scullery – from which agreeable smells of luncheon being prepared were issuing – to a boot room. ‘What’s your footwear like?’ was the earl’s next question. ‘Good enough’ – on seeing Rowlands’ well-polished and well-mended brogues – ‘but I’ll find you some gumboots. It’s pretty dry underfoot today, but you know what stable-yards are … You don’t use a stick, I notice.’

‘My wife is always telling me I should.’

‘Well, take this one,’ was the reply. A stout hawthorn walking stick was pressed into Rowlands’ hand. ‘You won’t need it for the stables, but we might walk up afterwards to take a look at the home farm.’

They passed the open door of the kitchen, and Swift put his head in. ‘Morning, Mrs M,’ he said, interrupting a dressing-down the cook was giving to one of her staff on the unsatisfactory polish this unfortunate had given to the knives.

‘Morning, my lord. And a fine one it is to be sure.’

‘This is Mr Rowlands. He’s from England. He’ll be staying with us for a few days.’

‘And doesn’t he look as if he needed some good Irish food and country air, the poor cratur,’ said the woman after a glance at the newcomer. Rowlands smiled at this, but didn’t think it required a reply. It had been a busy few months at work, and he’d been looking forward to his two weeks’ holiday in Cornwall; evidently, he looked as if he was in need of it. After a further exchange of pleasantries, the two men exited through the back door onto a cobbled yard.

‘Celia tells me you’re a detective,’ said Swift, whose conversational style seemed to be that of getting straight to the point.

Rowlands met this with equal directness. ‘Yes, of a kind. I don’t work in any official capacity, of course. But I have assisted the police, from time to time.’

‘Hmph. You know, you’re wasting your time if you think there’s anything here for you to detect,’ said the Irish lord as, accompanied by the dogs, they strolled across the yard. ‘My wife’s got some notion into her head that someone’s out to get me. But it’s all rot.’

‘Those letters were real enough,’ said Rowlands.

‘Ah, she told you about those, then?’ Swift didn’t sound too pleased.

‘Yes. And then there was what happened to the dog.’

‘That was an accident. Jasper was an excitable creature. He must have got out, and one of the local farmers thought he was worrying sheep. Whoever it was mightn’t have known it was my dog.’

‘But the note …’

Swift made a scoffing sound. ‘The Irish are a dramatic people,’ he said. ‘I should know – I’m part-Irish myself. That note, like the letters before it, was just somebody making a drama out of a perfectly ordinary, if regrettable, occurrence. In my view, the best thing to do with such things is to ignore them.’

They passed through a gateway. That they were now in the stable-yard proper was evident to Rowlands, from the smells of newly raked straw and fresh horse-droppings; of leather tack and warm horseflesh, familiar from his boyhood days. The sounds, subdued but unmistakeable, were those that human beings adopt when conversing with horses: the low crooning of a stable hand to the beast whose coat he was engaged in brushing; the soft clicking of a tongue by which a rider signalled to his mount that it was time to ‘walk on’. Swift led the way to the far side of the yard where the stables were, greeting this employee and that one en route: ‘Morning, Davy, morning, Mike. How’s the brown mare’s foot coming along?’

‘Grand, me lord. Sure, she’ll be lepping fences again in no time.’

‘Well, make sure you keep that poultice on until the thing’s healed.’ They reached the first of a row of loose boxes. ‘This is Lady Molly, the horse I had in mind for you,’ said Swift. ‘She’s as gentle as a lamb, aren’t you, old girl?’ He leant in to pat the mare’s nose, murmuring sweet nothings as he did so. ‘Give me your hand,’ he said to Rowlands; when the other did so, he found something in his palm: a sugar lump. ‘Always carry a few in my pocket for the beasts.’ Rowlands offered this tribute to Lady Molly and she took it delicately between her lips and crunched it with her strong teeth. He stroked her face, feeling the soft puff of her breath on his cheek. He could tell from the quiet way she submitted to his caress that this was an even-tempered creature. ‘I think you’ll do very well together,’ said Swift.

They moved along the row, coming to a halt in front of a stall three places along from the one occupied by the mare. ‘Now this,’ said Swift, ‘is another kettle of fish altogether. Name’s Lucifer. And doesn’t he live up to it, the devil! Proud as can be, aren’t you, my lad?’ He reached a hand in to pat the stallion’s neck, and there came a snorting and stamping of hooves as the high-mettled beast responded to this presumptuous contact. ‘Six-year-old. Thoroughbred. Came first in his class at the County Wicklow trials. Good jumper, too. Careful!’ he added as Rowlands reached out a hand to the horse. ‘He’s got a bit of a temper.’ This Rowlands had just discovered for himself, for as his hand touched Lucifer’s nose, the beast gave an indignant snort, and jerked his head away. ‘Behave,’ ordered his master. ‘Don’t you know a friend when you see one?’

‘Fine animal,’ said Rowlands, stepping back a pace to allow Swift to take charge.

Just then, one of the grooms came hurrying up. ‘Ah, me lord,’ he said. ‘I was just after giving himself a nice warm mash. Quiet him down a bit. Were you after taking him out, now?’

‘Not until first thing tomorrow, I think,’ was the reply. ‘He’s had one good ride already today. Rowlands, this is Mr Pheelan, my head groom. Pheelan, Mr Rowlands will be taking Lady Molly out this afternoon. You might get her ready. He’ll need a lead rein.’

‘Very good, my lord.’

‘I’ll lend you some clothes,’ Swift went on as he and Rowlands resumed their stroll. ‘We’re more or less the same size. And I’ve a spare pair of boots I think might fit you.’ Resigned to the inevitable, Rowlands nodded. It’d be good to get up on a horse again although he doubted whether he’d be able to go very far. But he was fast learning that, with these people, one was hardly worth noticing if one didn’t ride.

‘How many horses do you have here?’ he asked as, after a few more words with the head groom on matters of a technical nature relating to the type of reins, bits and saddles best suited to an inexperienced rider, they continued their walk.

‘Six, at present. That is, the two you’ve just met and two more, one of which is Celia’s horse, Delilah, and the other a gelding – Duke Humphrey. I’ll be riding him when we go out later. My brother doesn’t care for riding although he was brought up to it, the same as I was. The other two horses belong to a neighbour, who stables them here. In my father’s day, we kept a dozen hunters, as well as what he liked to call “good, quiet, ladies’ horses”, and ponies for the children. I’m thinking of getting a little pony for my boy, you know. Celia isn’t keen. But I think one has to start them young.’

Chapter Three

There was still an hour to go before lunch, said Swift. If Rowlands was interested, they could stroll up to the home farm. He wanted a word with his cowman, and it was a pleasant enough walk. The dogs would appreciate it, too. Rowlands said he’d be happy to come along, and the two set off across the fields. ‘You’ll need your stick now,’ said Swift, pausing to light cigarettes for them both. It was a glorious day, Rowlands thought, savouring the feel of the sun on his face, and the sweet smell of hay and wildflowers arising from the meadows on either side of the path. After they had been walking for a few minutes, Swift said as if there had been no break in the conversation: ‘Yes, I think Celia’s got herself worked up about nothing. The fact is, Rowlands, my family have lived in this part of Ireland for two hundred years. We’ve seen famine and revolutions come and go. Of course, there’s some resentment against us – the English, I mean – and why wouldn’t there be? We’ve treated the Irish abominably over the years. Now they’re getting some of their own back. Inevitably, some of the nationalist crew are getting a bit carried away.’

‘That’s one way of putting it,’ said Rowlands drily. ‘So you think it’s all a lot of … what did you call it? Dramatics.’

‘I do,’ replied Swift. ‘Listen,’ he went on earnestly. ‘I know these people. I don’t mean the Irish in general, I mean the people who live on or around this demesne. I’ve known them all since I was a child, and they know me. I can’t believe any of ’em would wish me ill. I grant you, there may be a few hotheads – young fellows who fancy themselves as “soldiers” for the Republican Army – but that’s all just hot air. Why, I could name you a few names, if it would make any difference … except that it wouldn’t. Taking these threats seriously is the best way of encouraging them, don’t you see? If … call him Paddy, or Mike … thinks he’s made an impression, he’ll be much more likely to keep on with his foolish tricks. Ignoring them’s the only way.’

Rowlands guessed that the unusual length of this speech was indicative of how seriously the speaker meant what he said. And so he held his peace as, having scrambled over a stile, they found themselves on the rough track that led to the farm. Swift was obviously the type who would only become more entrenched in his position, the more one tried to persuade him he was wrong. Rowlands began to see why Lady Celia, despairing of convincing her husband of the seriousness of the threats against his life, had called in reinforcements.