7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Blind Detective

- Sprache: Englisch

First published as Game of Chance under A. C. Koning. 1929. Blinded war veteran Frederick Rowlands has escaped the bustle of London to establish a secure life for himself and his family in the countryside. But everything is about to change when an old friend, Chief Inspector Douglas, asks for his assistance in tracking down the killer of a beautiful dancer. That there is a link between the murder and St Dunstan's, the institute for blind ex-servicemen of which Rowlands himself is a member, is only one of the puzzling features of the case. Transported back into the whirl of London in order to unravel the mystery surrounding the dead woman, the Blind Detective is caught up in a deadly game of chance. A series of breathtaking twists and turns force him to confront his past, and to risk everything - including own life - in the process.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 526

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

3

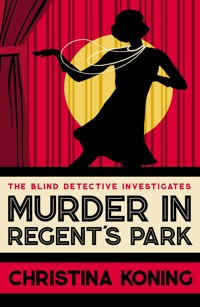

MURDER IN REGENT’S PARK

CHRISTINA KONING

In memory of my mother, Angela Vivienne Koning (1921–1991), who knew the original of the ‘Blind Detective’ rather better than I did.

Contents

Chapter One

A fox had got into the henhouse. There was blood on the snow, the girls said. When he realised what must have happened, he warned them away, not wanting them to see the worst of it. But it was too late, of course. Anne’s cries of distress when she saw the carnage – the soft, feathery bodies with heads torn off in what seemed a wanton fury of destruction – told him all he needed to know about how bad it was. ‘Go back to the house, both of you,’ he said, his anger at the senseless waste of it making him uncharacteristically stern. ‘At once, do you hear? Tell your mother on no account to let Joanie out of the house until I’ve finished clearing up here.’ His youngest daughter’s fondness for the ‘chook-chooks’ being uppermost in his mind as he began the melancholy task of disposing of the corpses.

From the silence which reigned over the entire field, he knew there was little chance that any of the flock had survived the onslaught. The irony was that it was in order to make the hens more secure that he’d built the large hut, whose door – he didn’t need to check – now hung open, a conduit for slaughter. Which of his two elder children had been careless enough to leave the thing unlatched was something else at which he could make a pretty good guess. Dreamy Anne, always with her head in the clouds, was the most likely culprit. Although, later that day, Margaret would come to him with a confession that it was she who’d left the door open. That was one thing about his children: they stuck up for one another – Anne, on one memorable occasion when they were visiting Edith’s brother in Richmond, having jumped fully clothed into the river in order to share the scolding her elder sister was about to receive for having got her feet wet.

Not that it mattered who was guilty – or not guilty – of the oversight, Frederick Rowlands thought grimly as he shovelled bodies into sacks. The sharp tang of blood, mingled with the perennial stink of chicken manure, was mercifully deadened by the extreme cold; even so, it was a disagreeable task. To say nothing of the loss of income it signified. Even if he’d been the sort of father to exact retribution (which he was not), he doubted whether the mild punishment of stopping his middle daughter’s pocket-money for a week would quite cover the cost of the disaster.

Nor was it the first setback they’d had in the two years since they’d moved from London to the wilds of Kent. First there’d been Dorothy and Viktor’s departure – which had been unavoidable, of course, but had left him running the farm alone; then there’d been that outbreak of Fowl Pest last spring which had decimated the flock, and from which, nine months on, they’d only just started to recover. Well, they could forget about any sort of recovery now. With what had happened that morning, they’d be lucky if they could make it to the end of the month without having to sell up.

No, it wasn’t what you’d call the best start to the year, he thought, as he finished tying up the mouths of the sacks with twine. There! That would keep the rats out until he’d time to build a bonfire to dispose of the bodies. It might be possible to salvage some that weren’t too badly mauled for eating purposes. He’d see what Edith thought about that; he supposed she’d have heard the news from the girls by now. Walking back towards the house, he braced himself for a tirade of recrimination. But his wife seemed uncharacteristically subdued. Perhaps it was the sight of his face as he walked in the door. ‘Is it bad?’ she merely asked.

‘Very bad,’ he replied. Having fallen down in this respect in the past, he now made it a point of principle not to keep things from Edith. ‘In fact,’ he went on, trying to keep his voice light, ‘I’d say it’s about as bad as it can be.’

‘Are we ruined, then?’

‘Oh, not quite that.’ He blew on his fingers, feeling the life come back into them. He had a dread of chilblains, his hands being – for him, more than for most others – essential tools of perception. ‘There’s still the tea shop.’ Although this, as they both knew, was a seasonal enterprise only. In the bitter January weather, with snow on the ground a foot deep, they were unlikely to sell many teas, or indeed, fancy cakes – even if they still had the eggs with which to make them.

‘Yes.’ She didn’t waste time, as some women might have, in pointing out this obvious fact. ‘Come and sit by the fire,’ she said. ‘You look half-dead with cold.’

‘I could certainly use a cup of tea.’

‘I was waiting for you,’ she said. ‘It’s just made. Here you are.’ She handed him his tea, then took a thoughtful sip of her own. ‘We could always sell something,’ she said. ‘My pearl necklace, for instance.’

‘We’re not selling your pearl necklace.’

‘I never wear it. And they’re quite good pearls, I believe. A cousin of Mother’s brought them back from China. We need the money,’ she added.

‘There are other ways of getting it.’ Although he couldn’t, at that moment, think of any. ‘I’ll write to Major Fraser after lunch. Perhaps he can suggest something.’ Even as he said it, he knew this was unlikely. The Major had his hands full enough as it was, trying to raise funds for the new rehabilitation centre, without being asked to solve a former inmate’s financial troubles. Still, it was worth a try. Because even though more than a decade had passed since Rowlands’ days at St Dunstan’s Lodge, still the organisation to which he knew he owed everything – his health, his sanity, even his marriage – kept a watchful eye on the vicissitudes of its members’ lives.

He was just threading the paper into the typewriter, and thinking of what he was going to say (but how on earth did one begin a begging letter?), when there came a ring at the door. ‘If it’s the Boy Scouts, I’ve already given,’ he sang out. But it couldn’t have been the Scouts, after all, because somebody had come in. There were voices in the hall: Edith’s, and another, which seemed vaguely familiar. The vicar’s, perhaps. There was a new chap at All Saint’s, wasn’t there? He must be doing his rounds. Funny weather to choose; still, you couldn’t fault a man for being keen. He adjusted the paper, then typed the date – Tuesday 1st January 1929 – and the address. ‘Dear Major Fraser,’ he began. ‘I expect you’ll be surprised to hear from me, after all this time …’

The door of the sitting room opened. Why was the vicar coming in here? He started to get to his feet, forcing a smile, although the last thing he felt like at that moment was engaging in polite chit-chat about the state of the church roof. But as it turned out, he didn’t have to. ‘Och, don’t disturb yourself,’ said a voice. It was, after all, one he knew. ‘I can see you’re busy just now. But if you could spare me a moment or two, I’d be grateful.’

‘Inspector.’

‘You look surprised to see me.’

‘I am, a little. What brings you here? Nothing untoward, I hope?’ As he said it, a dreadful thought occurred to him. He felt the blood drain from his face. ‘It isn’t … anything to do with my sister, is it?’

‘Och, no. Rest assured, it’s nothing that concerns her. Wherever she might be,’ added the policeman drily. ‘No, it’s you I’ve come to see. The fact is, I thought you might be able to help me.’

‘I can’t imagine how.’ Rowlands’ heart was still beating rather too fast. He took a breath to calm himself. ‘Please sit down, Inspector.’

‘It’s Chief Inspector, now,’ said the other, seating himself, with a groaning of springs, in one of their rather less than comfortable armchairs. ‘Not that you were to know unless you’ve been following my career in the newspapers.’

‘I can’t say I have. Well, congratulations.’

‘Thanks. You’re looking well, Mr Rowlands. Country life obviously suits you.’

Rowlands couldn’t suppress a grimace. ‘Well, it did suit me, up until now. Quite how much longer my wife and I will be able to keep on living here is anybody’s guess.’ At once he regretted saying so much; the man had that effect on him, evidently.

‘Oh?’ said Douglas. ‘And why might that be?’

Rowlands explained about the loss of the chickens.

‘Unfortunate,’ said the policeman, clicking his tongue. ‘But it’s an ill wind, as they say. Because there’s something I’d like you to do for me, Mr Rowlands. And while I can’t promise that it will solve your present difficulties altogether, I can make it worth your while.’ Before he could elaborate, or Rowlands could respond, there was a knock at the door, and Edith came in, carrying a tray. ‘I thought you might like some tea,’ she said. ‘And perhaps a little something after your journey.’

‘Scones,’ said Chief Inspector Douglas, with relish. ‘How very kind of you, Mrs Rowlands. Here, let me …’ He must have taken the tray from her because there was the sound of its being set down, rather too firmly, on the little bamboo side table. ‘Well,’ said Edith brightly. ‘I’ll leave you both to it.’

‘Charming lady,’ said Douglas as the door closed behind her. ‘You’re a fortunate man, Rowlands.’

‘I know.’

‘I’ll be Mother, shall I?’

‘If you like.’

Their visitor busied himself with pouring out the tea. ‘How do you like yours?’

‘What? Oh, just as it comes.’

‘That’s just how I like mine, too. Can’t abide stewed tea, mind. It has to be fresh and strong.’

‘Yes. Look here, Inspector … Chief Inspector, I mean. I’d like to know what this is all about.’

‘All in good time,’ said the other. ‘Why don’t you drink your tea, while it’s hot? Here you are.’ There was the faint percussive sound of a full cup settling into its saucer.

‘Just put it down on the table, would you?’

But Douglas appeared not to hear this simple request. ‘Here,’ he said again. ‘Take it.’

Exasperated at this small failure of communication – did the man understand nothing? – Rowlands held out his hand. If half his tea ended up on the carpet, it wouldn’t be his fault. But into his outstretched fingers came not the curved edge of one of his wife’s best porcelain cups but a straight, sharp edge that might have been that of a knife but was not; it was as thin, certainly, but lighter and less substantial. He knew what it was at once. His fingers went to the raised marks – really no more than pinpricks – in the upper left and lower right-hand corners. ‘The ace of hearts,’ he said.

‘Quite right,’ said Douglas, his satisfaction at the success of his ‘trick’ only too evident from his tone of voice. ‘I always said you were a sharp one, Mr Rowlands. Your tea’s in front of you, by the way. On the low table.’

‘Thank you. Perhaps now you’ll explain,’ said Rowlands, ‘what all this is about?’ He held up the playing card, between finger and thumb.

‘Willingly,’ replied the Chief Inspector. He took a sip of tea. ‘Lovely,’ he said. ‘Hot and strong. You’ll have to forgive my little subterfuge, Mr Rowlands. I had to prove something to myself, and you’ve helped me to do so. As to that particular card – not eighteen hours ago, it was found in the hand of a murdered woman.’

‘Christ!’ The card fell from Rowlands’ hand to the floor.

‘You might very well invoke our Saviour’s name, Mr Rowlands,’ said Douglas, with grim humour. ‘Although there’s precious little of His goodness and mercy in this sorry business, I’m afraid.’

Rowlands was still trembling with the horror of it. ‘You had no right,’ he said. ‘Supposing one of my girls had come in …’

‘Ah, I made sure to tell your wife we weren’t to be disturbed,’ was the reply. ‘I’m sorry for giving you such a shock. But it’s told me something else I needed to know.’

‘I can’t imagine what.’

‘Can’t you?’ said Douglas. ‘Well, perhaps you will when you know a wee bit more.’ He bent down, with a little grunt of effort, and picked up the card. ‘This,’ he went on, ‘is, as you perceived, a playing card. The ace of hearts, as you rightly said. A card of a particular kind, Mr Rowlands.’

‘A braille card,’ said Rowlands, impatient with what seemed to him an unnecessary spinning-out of the perfectly obvious.

‘Indeed. Which is how you came to identify its value and suit so quickly. But it’s also, we’ve discovered, in the nature of a calling card.’

Rowlands was silent.

‘Aye,’ said the policeman, helping himself to a buttered scone and biting into it with some relish. ‘A kind of message, if you like.’

‘I don’t follow.’

‘No, I don’t suppose you do.’ The Chief Inspector sighed, although whether the sigh was on account of human iniquity or because the scone he had just eaten was so delicious, was hard to tell. ‘Let me put you in the picture. That card you’ve just identified was found in the hand of one Winifred Calder – known as Winnie – called herself a dancer, late of Camden Town. About half past twelve last night, the woman with whom she shared rooms – name of Violet Smith, also a dancer – came back to find the place in darkness. Her first thought was that Winnie must’ve run out of shillings for the meter – but then she switched on the electric light and found the girl lying on the bed. She’d been strangled. Dead no more than an hour, the doctor reckoned.’

‘Have you any idea who did it?’

‘Not as yet,’ replied Douglas. ‘Although at first sight, it looked like a routine affair. Woman no better than she should be quarrelling with a boyfriend. The usual thing. But then we found this, your little ace of hearts, and it set us thinking.’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘I can see that it did.’ A thought occurred to him: ‘Can you describe the card?’ he said. ‘I thought we’d been over all that,’ replied Douglas. ‘It’s a braille card. The ace of hearts.’

‘I know. I just wondered if there was anything else distinctive about it.’

The Chief Inspector must have taken the card out of his pocket once more, for he said after a moment, ‘Nothing particularly distinctive, that I can see. The face is red and white; the reverse side’s red and black. That’s to say, there’s a border of red, surrounding a border of white, patterned with black dots. There’s something that looks like a flaming torch in the centre. Why? Is it important?’

‘No,’ said Rowlands. ‘It’s not important at all.’

‘I suppose you like to get an idea of the look of things, do you?’ said the other.

‘That’s right.’

‘I wonder,’ went on the Chief Inspector, ‘if your wife would mind if I lit my pipe in here?’

‘I’ve a better idea,’ said Rowlands. ‘If you’ve finished your tea, why don’t we take a walk into the orchard? We can speak more freely there.’ Because suddenly the room seemed airless, as if the terrible event which had been alluded to had sucked the atmosphere from it.

‘A fine idea,’ said the Chief Inspector, getting to his feet. ‘You’ll need to put a muffler on, though. It’s awful cold outside.’

Beneath their trudging feet, the snow had a brittle, icy feel. Rowlands wondered if it would snow again tonight. He sniffed: it was certainly cold enough. Beside him, Chief Inspector Douglas puffed away on his pipe; its pungent smoke hung on the still air. From a mile or so away across the fields, a dog barked. Otherwise it was utterly silent.

‘Aye, it’s been a bitter winter,’ said Douglas. ‘And no sign of a thaw yet.’ Rowlands made a sound indicative of agreement but said nothing more. ‘I take it,’ the policeman said at last when they had taken a turn around the orchard, ‘that you’ve worked out why it is I’m here?’

‘I imagine that it’s to do with that card. You have a notion that the perpetrator of this murder must be a blind man – otherwise why would he leave such a “calling card”, as you call it?’

Douglas laughed delightedly. ‘There!’ he said. ‘Didn’t I just say you were a sharp chap? Yes, that is what we’ve surmised although it begs the question, how did he manage it? Not so much the killing itself – there’s always the element of surprise in these cases, you know – but getting away unseen. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you that a man with such an affliction would tend to make himself conspicuous, rather than otherwise.’

‘No,’ said Rowlands, thinking wryly that being conspicuous was exactly what most blind men spent their lives trying to avoid.

‘So if we take it that our man is blind – and of course it might just be a trick of his to make us think so; what you might call a “blind” in itself,’ said the policeman, evidently pleased with this turn of phrase, ‘then it’s a question of checking the movements of each and every blind man who might have been in the vicinity of Camden Town between the hours in question – say ten and midnight. There were a lot of people out last night, of course, seeing the New Year in, and so it makes our job all the harder.’

‘I can see that it would. But I still don’t understand …’

‘… where you come into all this?’ The Chief Inspector came to a standstill, and stamped his feet. ‘Brr,’ he said. ‘Chilly. I think we may be in for another fall tonight. It seems to me, Mr Rowlands,’ he went on, ‘that you’re exactly the man to help us. Seeing as how a man in your situation must number amongst his acquaintance a large number of the kind of men we think we might be looking for – blind ex-servicemen, I mean …’

‘The answer’s no,’ said Rowlands.

‘… and seeing,’ the policeman continued as if Rowlands had not spoken, ‘that you’ve a particular interest in keeping things dark, as it were, with regard to your sister’s whereabouts.’

‘You said you didn’t know where she was,’ protested Rowlands. There was a sick feeling in the pit of his stomach. ‘You promised.’

‘I promised nothing,’ was the sharp rejoinder. ‘You know as well as I do that the police don’t strike bargains. What I said, if I remember rightly, was that we didn’t at present have the resources to go after her. Given that we’re at full stretch, as it is, without diverting valuable time and manpower to chasing off to South America, or wherever it is.’ Although he would of course know perfectly well where it was that Dorothy had fled, Rowlands thought bleakly. The dreadful events of two years before were doubtless as fresh in his mind as they were in Rowlands’. It struck him all at once that the place they were standing, beside the stump of the fallen apple tree, was the exact spot where he’d heard Dorothy’s confession, all those months ago. A blighted spot, he thought with a shiver.

‘Feeling the cold?’ enquired Chief Inspector Douglas. ‘We can’t have you catching a chill. Yes, the unpleasant truth of the matter, Mr Rowlands, is that I only have to say the word for your sister to be taken up. The fact that she hasn’t been so far is for the reason I’ve just given, and – well, because it’s suited me to leave her free. But it doesn’t mean that I mightn’t take a very different view if you can’t see your way to helping me.’

‘That’s blackmail.’

‘An ugly word,’ said Douglas. ‘I prefer to call it persuasion. And I’m not asking you to work for nothing, you know.’

‘That makes it worse. You’re asking me to … to spy on people I know. To be a paid informer.’

‘I’m asking you to talk to a few people, that’s all. To keep your ear to the ground, so to speak, and let us know if you hear anything of interest connected with this murder. You do know quite a lot of people in your situation, don’t you, Mr Rowlands?’

‘If by that you mean blind men, then yes, I do know quite a few. Some of them are my friends. But I suppose that counts for nothing with you.’

‘On the contrary,’ said Douglas. ‘It counts for a great deal. With a man like you, Mr Rowlands, one always knows where one stands. I’d call you a man of principle.’

‘A man prepared to compromise his principles, don’t you mean?’ They had by now arrived back at the house. A smell of roasting chicken, emanating from the vicinity of the kitchen, suggested that Edith was doing what she could to salvage something from that morning’s catastrophe. Troubled as he was by the conversation he had just had with Douglas, Rowlands couldn’t suppress a smile. That was his wife all over – always looking for ways of turning a bad situation to advantage. And it did smell rather good … although whether he’d feel the same once they’d been eating chicken for a week, he couldn’t say. It crossed his mind to invite Douglas to join them for dinner, but he decided against it in the same moment. After what had passed between them, to have the man sitting at his table, eating his food, and drinking his drink, would be hard to bear. As if he half-guessed this thought, Douglas murmured something about needing to make tracks. ‘No rest for the wicked,’ he said. ‘Nor for those in pursuit of ’em, like myself. Well, good day to you, Mr Rowlands. I’ll be in touch.’

‘All right.’ It seemed churlish not to offer his hand, and so he did so.

It was warmly clasped. ‘Good man,’ said the Chief Inspector. ‘I’m proud to be working with you. Oh, I know you’re feeling bad about this now,’ he added, resting his free hand for a moment on Rowlands’ shoulder. ‘But it will seem quite different when you’ve had a chance to think things over.’

‘So what did he want?’ asked Edith. It was later that evening; the girls had been put to bed and the news on the wireless listened to. Unemployment was up. Manufacturing down. They weren’t the only ones who were having a bad start to the year, Rowlands thought. Now his wife sat knitting in her chair by the fire, and he sat drumming his fingers and trying to concentrate, without much success, on the book he was reading. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The British Campaign in France: a heavy book, in every sense. He was still only halfway through the first volume, with another four to go. Braille books took up a great deal more room than the ordinary kind. But even if his reading had been the most frivolous of thrillers, he’d still have found himself distracted. He sighed, and laid the weighty tome aside. Two years ago, he’d have fobbed Edith off with some lame story or other. Now he said: ‘He wants me to spy for him.’

‘Oh?’ She didn’t sound as shocked as he’d expected at this bald statement of fact. ‘Well, it wouldn’t be the first time.’

‘No.’ He didn’t need to point out that, on the occasion referred to, he’d resisted all Douglas’s attempts to make him ‘peach’. Things were different now. ‘You’d better tell me what it’s all about,’ she said. ‘That is, unless he’s said not to.’

‘He hasn’t.’ As briefly as he could, he outlined the salient facts. When he’d finished, she was silent for a moment. ‘So they think it was a blind man who did it?’ she said at last. He shrugged. ‘So it would appear. Although it seems rather a long shot to me.’

‘Yes. I suppose the card couldn’t have got into her possession – the girl’s, I mean – by accident?’

‘Unlikely. It was in her hand when she was found. One assumes it must have been put there after death, because … Well, let’s just say the possibility that she was clutching it all the while that she was being murdered seems rather a slender one.’

‘I see that.’ Her needles clicked. ‘How beastly it all is,’ she said.

‘Yes. You know, I rather wish you hadn’t asked me about it.’

‘Oh, I wanted to know,’ Edith said. ‘I believe one should face these things. I must say,’ she went on, in a reflective tone, ‘it does seem extraordinary that the police don’t have anything else to go on, apart from this … playing card. I mean – what about fingerprints?’

‘He’d have worn gloves.’

‘Surely somebody must have heard or seen something?’ she persisted.

‘Well, if anybody did, I’m sure the police will track him down.’

‘Or her.’

‘What? Oh yes, I see what you mean,’ he said. ‘Although it might prove a bit tricky, finding this “him” – or “her”. Given that it was New Year’s Eve. An awful lot of people would have been out and about.’

‘All the more chance that one of them saw something,’ said his wife.

‘Perhaps.’ He hesitated a moment, then made a decision. ‘There is one other thing,’ he said. ‘That card. It wasn’t just any card.’

‘It was a braille card, I know.’

‘Not only that. The design on the back was a flaming torch.’

‘Then that means …’ She broke off. In her excitement, she let her needles fall. ‘Fred, are you sure?’

‘The Chief Inspector described it to me.’

‘Did you tell him what it meant?’

‘No. I wanted to think things over first. Because if it’s someone at the Lodge …’

‘You don’t really think it could be, do you?’

‘I don’t know,’ he replied.

‘I mean, you can buy those St Dunstan’s cards everywhere.’

‘That’s true enough,’ he said. ‘But you must see how bad it looks. If I’m to take this on – this sleuthing business – there’s a chance I might find out things I’d rather not find out. I suppose,’ he added, ‘it’s a chance I’ll have to take.’

Chapter Two

A brief paragraph about the Camden Town murder appeared in the newspaper next day; Edith read it to him at breakfast after the the girls had been sent upstairs to clean their teeth. To the information Rowlands already had, it added not a great deal more. A Miss Winifred Calder, aged twenty-two, had been found dead from strangulation in the early hours of Tuesday morning. The body had been discovered by her friend, Miss Violet Smith (stage name: Violetta L’Amour), who worked as a dancer at the Hippodrome Theatre, and had been returning from an after-show party. ‘Winnie was a very quiet sort,’ Miss Smith was quoted as saying. ‘Kept herself to herself, really.’ She had known Miss Calder only a few weeks, she said, when the former had answered an advertisement to share furnished rooms. ‘It was awful,’ she said. ‘Finding her like that. Still warm she was. I don’t think I’ll ever get over it.’

Rowlands supposed that the police would already have got whatever there was to be got from the loquacious Miss Smith; still, a visit to Camden Town wouldn’t go amiss, if only because it would give him a better idea of the lie of the land. His memory of most parts of London was good – it was, after all, the city in which he’d spent most of his life; even so, it wasn’t until he’d walked around a bit and got the smell of the place, so to speak, that he’d know what he was about. A reply to his letter had come by the evening post. The Major would be happy to see him: would midday on Thursday suit him? He replied by return that it would. It would give him time, he thought, to visit the scene of the crime; Camden being conveniently close to Regent’s Park.

So it was that he found himself on the half past eight train to Charing Cross, hemmed in by the well wrapped up bodies of a carriage load of City workers. He hadn’t been part of such a crowd for a very long time; funny to be back in it now. Very little seemed to have changed in the eighteen months he’d been away: there was still the same dull shop being talked by some; the New Year’s Day football results chewed over by others. There was the rattle of newspapers being read and the phlegmy sound of noses being blown. A smell compounded of stale tobacco, body odour and woollen overcoats. He wasn’t sorry to be out of it all, and yet in a strange way, he rather missed it.

In Camden High Street, the snow had turned to slush, churned up by the feet of passers-by along the pavement, and in the road itself by the constant traffic of heavy goods vans, trams, buses, taxis and drays, each bringing its own particular brand of noise and stink. But then that was the nature of the district – a rackety place, in Rowlands’ opinion. From the boozy gaggle of drinkers awaiting opening time on the pavement outside the Old Mother Red Cap to the market traders bawling their wares in Inverness Street, there was always somebody creating a disturbance. Just now, as he approached the bridge that ran over the canal, an altercation was in progress. A butcher’s boy pushing a handcart had chosen to cross the street at the same moment that a lorry full of coal had come thundering out of Hawley Crescent, nearly crushing boy and handcart in so doing. Now both parties voiced their opinion of the other in no uncertain terms.

‘You fucking eejit. You could’ve killed me!’ shouted the youth with the handcart as Rowlands drew level with him, so that for an instant he thought it was he who was being thus addressed.

‘Shouldn’t ’ave been in the fucking way, then, should yer?’ was the no less vehement reply.

‘I’ll get the coppers onto you, I will!’ retorted the butcher’s boy. ‘That’s ten shillings’ worth of beef you’ve gone and spoilt. Look at it! All over the street.’ This had evidently been the fate of the handcart’s load. ‘Didjer see what happened?’ the lad then demanded of Rowlands.

‘I’m afraid not.’

The other made a sound indicative of disgust.

‘Dust it down – it’ll be as good as new,’ jeered the coalman from the safe elevation of his truck. ‘Go lovely with a bit o’ mustard on Sunday, that will.’

Behind them – to judge from the impatient honking of horns and shouts of ‘Get on with it!’ – a queue of traffic was building up. Rowlands left them to it and made his way, with a degree more caution than usual, along the icy street. Falling over was bad enough, but to walk slap bang into a coal truck – or have one crash into you – just because you hadn’t been paying attention … well, you’d have only yourself to blame, that was all. Because paying attention was what you had to do at all times. Stopping and listening at the lights wasn’t the half of it. It meant keeping all your wits about you – all your senses, too. Equipped as he was with one fewer than most people had, still he tried to make the most of those that remained. In the dozen years which had passed since a piece of shrapnel had taken away all but a fraction of his sight, he’d had to learn ways of coping. You had to develop a kind of inner eye, he thought; a preternaturally sharp awareness of all that was going on around, that drew on sense impressions – smell, sound, touch, taste – and memories.

Fortunately, he’d always had a good memory: it was what had got him through school, and later through those evening classes at the Working Men’s College in St Pancras, which in turn had enabled him to leave the factory for the job at Methuen. It had been Harry who’d encouraged him, of course. ‘With brains like yours, you ought to train for a teacher – or a solicitor’s clerk,’ his brother had said. ‘You could do a lot better than this job, at any rate.’ Although he hadn’t minded working at The Lamp, which was the local name for the Swan Edison factory. It was called that, because that was what it made; later, it would turn out shells for the war effort. He’d started on four shillings a week, sweeping up under the trestle tables where the women sat, assembling lamps. Later, he’d moved to the factory floor with the rest of the men.

His task was collecting the waste that fell from from the machines that made the electric bulbs. Little airy things of spun glass they were, with a glowing thread at the heart. When he was sixteen, he was given a machine of his own to operate. It was exacting work, but not as punishing to the nerves and muscles as working in a factory that made heavy machinery. This, though demanding enough, was classified as light rather than heavy industry. And of course what it produced was light itself. It was something he’d found quite magical. That, thanks to the little bulbs of glass with their tungsten filaments he and his fellow workers turned out by the thousand each day, you could make the sun come out, banishing darkness at the touch of a switch.

Yes, if it hadn’t been for Harry he’d never have got the job in the first place. And it was Harry who, when he’d turned eighteen, had persuaded him it was time to move on. And so he, Fred, had started at the College, two nights a week, studying book-keeping and copy-editing. At twenty, he’d got a job checking proofs at Methuen, earning three pounds a week. When the war came, he’d just been promoted to Senior Copy Editor. It had been a good job – one he’d hoped to return to, although of course after what happened, there was no question of that. But it had occurred to him since that the work, exacting as it was, had helped to develop his ‘eye’ for detail – for the small error that, in a page of otherwise perfect text, threw the whole into disharmony.

Now he stood at the junction of Camden High Street and Kentish Town Road, waiting for the lights to change. He could tell that this was imminent from the sound of idling engines – a Talbot’s, he rather thought, and a Vauxhall’s, amongst others. A church clock – St Michael’s? – struck the half-hour. He’d better get a move on if he were to be at Regent’s Park by midday. He drew a breath of the icy air which tasted faintly of coal smoke. Someone in one of the houses nearby was frying bacon. Lovely smell. His mouth watered. The house he was looking for was the one on the corner – one of a terrace, he seemed to recall, at the entrance to Jeffrey’s Street. If he hadn’t already known it, he’d have guessed this was the place, from the fact of there being a policeman standing outside it. He discovered this when he attempted to approach the front door and found his way barred by a large, serge-clad body.

‘Sorry, sir. You can’t go in there,’ said a voice. A young man’s voice, Rowlands thought: no more than eighteen, at a guess. Rowlands assumed a perplexed expression.

‘This is Number Three, The Laurels, Kentish Town Road, isn’t it?’ he asked.

‘It’s Kentish Town Road, right enough. As to the rest of it, I couldn’t say,’ replied the other. ‘Only you can’t go in here, sir – not unless you live at this address, and I reckon you don’t, sir. Those are my orders,’ he added, with a touch of pride. ‘No unauthorised persons is to enter without permission. Didn’t you see the notice?’

‘No,’ said Rowlands. He gave an apologetic shrug. ‘I can’t, you see. Or not well enough to read notices, anyway.’ As the truth of this dawned upon the young policeman, he became all stammering confusion. ‘I’m … I’m ever so sorry, sir. I never …’

‘That’s quite all right, Constable. It is “Constable”, isn’t it, not “Sergeant”?’

‘Oh yes, sir,’ said the other, sounding pleased as Punch at the idea that he might have been taken for his superior officer. ‘I only joined up a month ago. Still a probationer, in fact.’

‘They give you all the difficult jobs, I shouldn’t wonder,’ said Rowlands.

‘Not half, sir.’

‘Standing about in the cold all morning being one of them, I suppose?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Been here long, have you?’

‘Since half past six. My relief comes at midday,’ said the constable. ‘And won’t I be glad,’ he added fervently.

‘Yes, it’s pretty cold still, isn’t it?’ observed Rowlands, drawing the cigarette pack from his pocket. ‘And not even a warm drink or a smoke to keep you going.’ He fumbled for his matches and proceeded to light up, turning his back to the wind to do so. ‘Beastly windy on this corner! Quite a job to light up. I say,’ he went on when the gasper was finally lit, ‘you wouldn’t care for one, would you?’ He held out the pack. The young policeman hesitated a moment.

‘Thank you, sir,’ he said at last. ‘But we’re not supposed to smoke on duty.’

‘Of course. Rules is rules, eh?’ Rowlands exhaled a lungful of aromatic smoke. ‘If you like,’ he went on casually, feeling a rotter for what he was about to suggest, ‘I could keep cave while you go around the corner and have your smoke out of the wind. Anyone comes along, I’ll sing out.’

‘Well …’

‘Old trick from my army days,’ said Rowlands. ‘Two of us out on patrol at a time. Not supposed to smoke either. Danger the enemy’d see the light, you know. A lighted cigarette made a good target. So what we’d do was this: one of us’d light up while the other held his waterproof cape out as a kind of shelter. Cut off the wind, you see, and prevented Fritz from taking a sighting. Then if the one doing the shielding spotted an officer approaching, he’d give his Pal a nudge. Rules,’ he added, drawing deeply on his Churchman’s, ‘are sometimes made to be broken.’

‘Perhaps just the one, then, sir,’ said the young man, his resolve now utterly broken down by the enticing smell of the tobacco. ‘There’s only two left in the pack,’ said Rowlands, handing it to him with the box of matches. ‘Keep the other one for later, why don’t you?’ Muttering his thanks, the policeman walked off around the corner into Jeffrey’s Street. Rowlands waited until the sound of his footsteps had died away before trying the front door. It was unlatched, as he’d hoped – the to-ings and fro-ings of police officers over the past few days having made this a necessity, he guessed. Nothing stirred as he reached the first floor landing, although he supposed from what the policeman had said that there must be other tenants in the place. Perhaps they were all out. Just as he had the thought, a door creaked open.

‘’Oo’s that?’ demanded a voice. Elderly. A woman’s. He turned his head towards the voice.

‘Good day,’ he said pleasantly. ‘I’m looking for Miss Smith.’

‘’Er!’ was the reply. ‘You won’t find ’er. She’s gorn off. Staying with friends,’ the old woman said scornfully. ‘“Friends”! I know what sort of “friends” they are. If you ask me,’ she went on, although he hadn’t said a word, ‘it should’ve been ’er what got it in the neck, and not t’other one. Coming an’ going at all hours. It ain’t decent,’ she shouted after him as, with a murmured apology, he pushed past her. Under other circumstances, he’d have let her ramble on, because there was usually something to be gleaned from even the most inconsequential talk, but just now he hadn’t time. Leaving her muttering balefully to herself on the landing below, he climbed the short flight that led to the attic floor. There were two doors; the first was locked. The second opened easily.

If Rowlands had been in any doubt as to whether he’d come to the right place, the first breath he took would have convinced him. It wasn’t just the stuffiness of the air, as of a room too long closed up, but something else – something harder to define. Perhaps it was no more than the knowledge of what had taken place in that room, three nights before, that made the hairs on the back of his neck stand up on end – he couldn’t say. Only that he felt a powerful sense of unease … no, it was more than that. It was fear. From his days as a gunner, he recalled the way that, after the gun was fired, one’s ears rang for minutes afterwards with the roar of it. It was like that now; only instead of waves of sound, what reverberated from the walls of this mean little dwelling was the echo of a woman’s terror.

He knew – from what particular source he couldn’t have said – that strangulation was not a quick death. It could take as long as three minutes while the victim fought, and gasped for air, and lost consciousness momentarily, before waking to fight some more. From the waves of fear and pain he could feel in the room, he conjectured that Winnie Calder had struggled more than most. Bile rose in his throat. He forced himself to take a step into the room, then another, feeling his way cautiously between the various items of furniture with which the flat was cluttered. Here was a deal table, with one, two, three chairs – none of them matching. Had they sat here, Winnie and her killer, on either side of the table, to consume whatever it was the bottle contained, that had been left standing at its centre? He picked up the bottle, unscrewed the cap, and sniffed. Gin. Of the glasses from which the two had drunk – as surely they had drunk? – there was no sign; they’d been taken away as evidence, he assumed.

In front of the gas fire was a divan, piled with women’s clothes; his exploring fingers found a pair of stays. He dropped them hastily. A smell of stale perfume and sweat rose from the dropped garments. Among the limp heaps of art silk undergarments, and not-quite-fresh blouses, he found a silk stocking, missing its fellow. Had that been the instrument of Winnie Calder’s destruction? His skin crawling, he moved towards where he guessed the bedroom must be. He knew from what the Chief Inspector had said that it was there that the body had been found. But even if he had not been told, he would have known it. Because here, the feeling of terror was at its most intense. You could almost taste it, he thought, with a shiver of disgust. Had she led him inside, poor unsuspecting Winnie, only to find there was no way out, and that this was to be her tomb?

His fingers fumbled behind him at the door. The key, as he had guessed, was on the inside of it. And so the murderer had gone about his business, safe in the knowledge that he would not be disturbed. Were someone to return unexpectedly, all he had to do was to wait until the coast was clear before letting himself out. Winnie Calder and Violet Smith must have had some sort of arrangement as to which had the use of the bedroom, Rowlands thought. Whoever had ‘company’ would lock the door – just as the killer had done – leaving the other to make her bed on the divan. Which was no doubt what Violet – or Violetta L’Amour, as she’d called herself – would have done if the bedroom door had not stood open. He pictured the scene: Violet stumbling tipsily up the attic stairs at midnight, and finding the flat in darkness. Grumbling to herself as she fumbled for the light switch, ‘Might’ve left a lamp on for us’, then seeing the door of the bedroom ajar: ‘Win! You awake? I’ve had such a night, you wouldn’t believe.’ Opening the door. ‘Winnie! Wake up! I want to talk. Don’t be a spoilsport, Win …’ Reaching to switch on the bedside lamp. Then the sight that met her eyes …

He’d reached the foot of the bed: an iron bedstead it was, with a cheap horsehair mattress. It had been stripped, of course. Fighting back the waves of nausea which threatened to overwhelm him, Rowlands forced himself to stand there, in that place of horror, and bring his thoughts to bear on what had happened there. The desperate, near-silent struggle which had taken place on this bed between a woman about whom he already knew too much and a man of whom he knew nothing. Or almost nothing. He knew that the man had climbed the stairs, as he himself had done, a few minutes earlier; that he’d sat at the rickety table and drunk gin from a greasy bottle, and then – having taken a silk stocking from the slatternly heap on the divan – had followed the girl into the bedroom and locked the door behind him. That he’d moved swiftly and surely across the room, to where the girl was undressing, or perhaps already lying on the bed. That, without giving her time to react, he’d slipped the stocking around her throat. Had twisted it until it tightened, into a ligature.

Rowlands found he was trembling with the sheer effort of making himself stay in the room. He could feel sweat on his upper lip. He gripped the rail of the bedstead so tightly he felt his knuckles crack. The place was in darkness when she got back … It was Violet Smith he meant. Yes, the flat had been in darkness; he remembered that Douglas had said so. Didn’t that suggest that the man who’d done this dreadful thing had been accustomed to moving about in the dark? That he was in fact a blind man? He did not want to believe it – and yet the implication was all too obvious.

A floorboard creaked. He felt his blood turn to ice. There was someone in the flat – he was sure of it. Hardly daring to breathe, he stood frozen to the spot, straining his ears to catch the faint sounds from the next room. The sounds of someone breathing. Of someone moving quietly around. The wild thought that it must be the murderer, returned (as murderers were said to do), possessed him. He drew a deep breath. Murderer or not, he’d meet the fellow face-to-face. Suiting the action to the thought, he turned to face the door, which he’d pulled shut behind him, and which was now slowly opening. There was a moment’s startled silence. Then: ‘What the devil are you doing here?’ said a voice.

Rowlands breathed again. ‘Hello, Chief Inspector,’ he said innocently. ‘I was just taking a look around.’

‘So I see,’ said the other drily. ‘I suppose you know that members of the public are strictly forbidden to enter a building where a crime has taken place until the police have finished with it?’

‘Yes, I realise it’s a bit irregular.’

‘“Irregular” isn’t all it is. There’s the small matter of corrupting an officer of the law to take into account.’

‘I hope you won’t be too hard on him,’ said Rowlands. ‘Coming up here was entirely my own idea. He’d not the faintest notion of what I was up to.’

‘I don’t doubt it,’ replied the policeman. ‘He needs to be a bit sharper, in my view. Silly young fool. I’ve already torn him off a strip for deserting his post.’

‘Oh come now,’ said Rowlands. ‘It was only for a moment.’

‘It need only take a moment for a crime to be committed,’ said Chief Inspector Douglas grimly. ‘I must say, Mr Rowlands, this wasn’t what I was expecting from you. I rather hoped by now you’d have got on with that bit of investigation we talked about.’

‘As a matter of fact, I was just on my way to Regent’s Park Lodge,’ said Rowlands.

‘Good.’ replied the Inspector. ‘I can give you a lift, as it happens. I’ve a car waiting.’ Ushering Rowlands ahead of him out of the door, he closed it behind him. They descended the stairs to the cramped hall, which had the smell of dust, boiled cabbage and bad drains, that houses of this kind often had. The Inspector opened the front door, and the noises of the street rushed in – a dog barking, a child crying, a dray rumbling past – sounds that seemed to Rowlands, after the oppressive quiet of the flat, to speak of life, and warmth, and welcome normality. Two steps led to the little railed off area fronting the street. ‘That’ll do, Jones. You may stand at ease.’ This, from the Chief Inspector’s sharper tone, was to the young policeman Rowlands had bamboozled, whose feelings towards his deceiver he – Rowlands – could very well imagine. ‘I shall want a detailed report,’ Douglas went on, still to his subordinate, ‘of everyone who passes this spot – man, woman or child – between now and twelve hundred hours – is that clear?’

‘Sir,’ replied the young man, in a voice that conveyed a good deal of the emotion he was feeling. ‘Good. Carry on, then.’ Just then, a car pulled up alongside, and the driver got out. ‘You took your time, Andrews,’ said the Inspector as the former went around to open the door. ‘Yes, sir. Beg pardon, sir.’

‘This is Mr Rowlands. You’re to to drop me off at the station first, and then you’re to take him to Regent’s Park Lodge.’

‘Sir.’

‘And on the way,’ Douglas said to Rowlands as both got into the back of the big Wolseley, ‘you can tell me what conclusions you’ve come to about our murderer.’

‘Oh, I think it’s a bit early for that, don’t you?’ said Rowlands. ‘I mean, the only couple of bits of evidence we’ve got are pretty insubstantial, to say the least.’

‘And what pieces of evidence are those?’ asked the policeman slyly.

‘I … well … the playing card, obviously,’ replied Rowlands, cursing himself for his blunder.

‘You said two pieces of evidence,’ persisted Douglas.

‘Yes. You said the flat was in darkness when Miss Smith returned to it. She herself said that the body was still warm. It occurred to me,’ said Rowlands reluctantly as the car sped along Arlington Road and turned into Delancey Street, ‘that he – the perpetrator – might still have been on the premises when she – Miss Smith, that is – entered the building. It would have been easy enough for him to let himself out and slip past her on the stairs.’

‘But what makes you think …’ began Douglas. Then he gave a satisfied chuckle. ‘I see what you’re driving at. You mean the flat was in darkness because he didn’t need to see what he was doing. He could manage perfectly well without the light.’

‘Yes,’ said Rowlands. ‘That is what I meant. It doesn’t prove anything, but …’

‘It’s certainly food for thought,’ said the Chief Inspector.

Chapter Three

‘So,’ said Ian Fraser when the usual pleasantries had been exchanged, and they were comfortably ensconced in the room he called his study, which had once been the drawing room when the house was in private hands. ‘What can I do for you?’ They were sitting on either side of a good fire that was presently singing away to itself and throwing out plenty of heat so that Rowlands – still shaken by his visit to the drab furnished rooms where Winnie Calder had met her death – felt himself relax for the first time that day. The warmth of the fire, combined with that of the tea he’d just drunk, and the slices of hot buttered toast he’d just consumed, produced a pleasant drowsiness, against which he knew he’d have to guard.

Because, notwithstanding the simple animal pleasures of being warm and well-fed – to say nothing of the pleasure he felt in being back here again, at the Lodge – the fact remained that this visit was nothing but a sell: a fraud he was about to perpetrate on a man he liked and respected; a man to whom he owed a debt of gratitude. Hadn’t the Major (as he always thought of him) been the man who’d rescued him from the slough of misery into which he’d fallen after being discharged from hospital, in the autumn of ’17? Then he’d been fit for nothing; a useless wreck. The Major had given him his life back. By taking him on at the Lodge, he’d offered Rowlands not only the chance to learn new skills, which in turn had enabled him to earn a living, but had given him back his self-respect. And this was how he was going to repay him: with lies and evasions.

He took a deep breath. ‘Well …’ he began; then stopped. He couldn’t bring himself to do it: to pull the wool over the Major’s eyes. Spinning some yarn to cover up his true intentions. It went against everything he thought was right.

‘I rather gathered, from your letter,’ said the Major, perhaps attributing a different cause to Rowlands’ silence, ‘that things hadn’t been going as well as might have been expected – with the farm, I mean.’

‘No. The fact is …’

‘These are difficult times,’ said the older man. ‘A lot of people are struggling. This hard winter we’ve been having hasn’t made things any easier.’

‘That’s true,’ said Rowlands. He was feeling more and more awkward. Damn Douglas. He’d half a mind to tell him to take a running jump. Let him get his information another way. But then he remembered Dorothy. The way she’d clung to him, tears streaming down her face, that last time on the quayside at Southampton Docks. Could he really take the risk that the Chief Inspector wouldn’t carry out his threat of having her arrested if Rowlands refused to co-operate? And so he made himself go on: ‘We’ve had some setbacks, I have to admit. In fact, the farm’s not really what you’d call a “going concern”. But it wasn’t about that I wanted to see you.’

‘Oh?’

‘The fact is,’ said Rowlands, hating himself for the ease with which the lie emerged, ‘I’ve been wanting to organise a reunion.’

‘I see,’ said Major Fraser, although he clearly didn’t.

‘A get-together, d’you see?’ Rowlands plunged on. ‘Of all the London Pals – I mean, of course, anyone who’s living in the London area as well as those who served in London regiments. One loses touch so easily.’

‘Indeed,’ said the Major. ‘And what form would this … ah, reunion be likely to take?’

‘I suppose that depends on the number of men who want to take part,’ replied Rowlands smoothly. ‘Of course,’ he added, with a laugh he hoped didn’t sound as false to the Major as it did to him, ‘there’s a chance we might end up with no more than a few chaps in a pub somewhere … that is, if not very many decide to come.’

The Major considered this. ‘It might be rather jolly, all the same. And if you get a bigger turnout?’

‘Well,’ said Rowlands. ‘That’s where I was hoping you’d come in. Could we hold our get-together here, do you think?’

‘I don’t see why not,’ replied the other. ‘In fact, I think it’s a splendid idea. You can use the Rec room, if you like. I suppose you’ll be wanting a bar?’

‘It might help to attract a few more people,’ said Rowlands.

‘Splendid,’ said the Major. ‘Consider it done. I suppose we’ll have to wait and see what kind of numbers we get before deciding.’

‘Rather,’ said Rowlands. ‘As you say, we ought to see what kind of response we get when we contact people. With regard to that,’ he went on, keeping his tone casual, ‘I’ll need names and addresses. Telephone numbers, too. I don’t suppose …’

‘Oh, we can supply all of that,’ said the Major. ‘Names by the score. You’d better check with me before you start getting in touch, though. Just in case. Some of them have died, you know,’ he added gently, in case his meaning had not been made sufficiently clear. ‘We try to make a note of it when it happens, but we’re not always as up to date as we’d like. I’m sure you wouldn’t want to be the unwitting cause of distress to anyone.’

‘No,’ said Rowlands.

A silence ensued which neither seemed in a hurry to break. Rowlands took a sip of his tea, recalling other times he’d sat there, in just that spot in front of the fire, talking things over with this man whose opinion he valued above all others. There’d been one time in particular, two years ago, after Gerald Willoughby died … He flinched at the memory. ‘So,’ said the Major, breaking into these thoughts, ‘if that’s all you need from me, I don’t see any difficulty in achieving it. Would you like to borrow Doris for a day or two?’ This was his secretary, Rowlands surmised. ‘I’ll have to check that she’s all right about it, of course, because it’ll mean some extra work, what with all the telephoning, but I feel sure …’

‘Oh, I wouldn’t expect her to do that,’ said Rowlands quickly. He smiled. ‘As you may recall, using the telephone’s rather in my line.’