Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

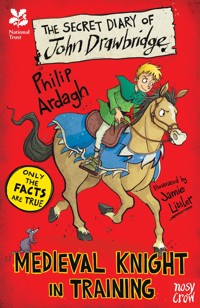

- Serie: Secret Diary Series

- Sprache: Englisch

Facts meet fiction in this exciting, intricate Victorian detective story! Jane Pinny has moved to the very grand Lytton House to be a Maid Of All Work. And being a Maid Of All Work means that she has to do... well, ALL the work, obviously! Cleaning, dusting, scrubbing, washing - there's SO much to do in a Victorian country house. But when a priceless jade necklace belonging to the lady of the house disappears, Jane turns accidental detective (with the help of her best friend, a pigeon called Plump...) - can she solve the mystery of the missing jewels before it's too late? Perfect for fans of Horrible Histories, filled with amazing facts and historical trivia, with an exciting story and brilliant illustrations, you won't be able to put this SECRET DIARY down! Read the other books in the series: The Secret Diary of John Drawbridge, Medieval Knight in Training The Secret Diary of Thomas Snoop, Tudor Boy Spy The Secret Diary of Kitty Cask, Smuggler's Daughter

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 89

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For all those who have loved animals, and have had animals love them back.

PA

To the Pencil Wobblers, for all their anything-but-wobbly support.

JL

Day 1

This morning, I was talking to Plump, the big, fat pigeon what lives on the ledge outside me bedroom window, and he says I should keep a diary.

“What, me?” I says.

“Yes you,” he says.

“But I’m just a maid,” I says.

“You’re a human being,” he says and gives me one of them head-bobbing pigeon stares that you can’t argue with.

“So what?” I says. “Everyone’s a human being.”

Then Plump gives me another one of them stares.

“Sorry,” I says, “but you knows what I mean. There ain’t nothing special about me.”

“You are someone who’s not satisfied with your lot,” says Plump. “You’re a girl going places.”

“I’ll still be just a maid,” I remind him.

“You’re friends with a talking pigeon, ain’t you?” says Plump, now pacing up and down his ledge. “Don’t that make you special?”

I smile. “I suppose it does,” I says. “But I still can’t write no diary.”

“Why not?” he says.

“’Cause I can’t write much more than me name,” I says.

Plump tilts his pigeon head to one side, like he always does when he’s having a really SERIOUS think. “I have an idea, Jane,” he says. “A bloomin’ brilliant idea.”

(He calls me Jane ’cause that’s me name: Jane Pinny.)

“What?” I says.

“You tell me what to write and I’ll write it for you,” he says.

I laughs. “Pigeons can’t write, Plump!” I says.

“Pigeons can’t talk neither, can they?” he says, “but that ain’t stopped me.”

“True,” I agree.

“So you’ll keep a diary. Deal?” he says.

“Deal,” I says. And I ain’t about to break my word to me bestest friend.1

1