Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

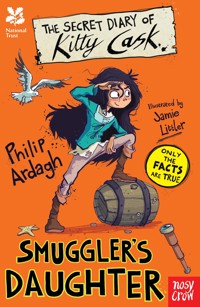

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

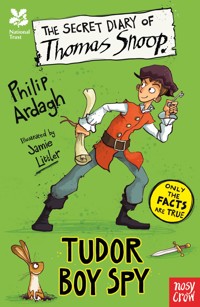

- Serie: Secret Diary

- Sprache: Englisch

Fact meets fiction in this thrilling story of 18th century smuggling and intrigue! Kitty Cask is a smuggler's daughter. In the Cornish coastal village of Minnock, Kitty and her family make their living as "free traders" - secretly bringing contraband goods into the country while evading the corrupt Redcoats who work for the King. Kitty isn't supposed to be involved in any of her father's schemes... but she's very good at creeping out at night, and before too long she is caught in the thick of the action - salvaging shipwrecks, staging prison-breaks, and staying one step ahead of the tyrannical excisemen! With an exciting story and brilliant illustrations, and filled with amazing facts and historical trivia, you won't be able to put this SECRET DIARY down! Read the other books in the series: The Secret Diary of John Drawbridge, Medieval Knight in Training The Secret Diary of Jane Pinny, Victorian House Maid (and Accidental Detective) The Secret Diary of Thomas Snoop, Tudor Boy Spy

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 92

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also available:

THE SECRET DIARY OFJohn Drawbridge, Medieval Knightin Training

THE SECRET DIARY OFJane Pinny, Victorian House Maid(and Accidental Detective)

THE SECRET DIARY OFThomas Snoop,Tudor Boy Spy

My name is Kitty Cask. That’s Kitty short for Katherine with a ‘K’, but I’ve never had anyone call me by that name. My home is in Cornwall1, and it’s one of a cluster of cottages clinging to the hillsides in the village of Minnock where the river flows out into the English Channel.

The French call the Channel ‘La Manche’, because they think the strip of water looks like a coat sleeve. Trust them to think of fashion! A Frenchie2 is more interested in the cut of his trousers than in ruling the waves! It’ll always be the English Channel, ’cause it’s OUR sea, though calling it the Cornish Channel would be better still! Sometimes angry, with raging white waters, it tosses aside boats like my little sister, Esme, throws her toys from her cradle, wind howling like when Esme has a tooth comin’ through. But, more often than not, it is our friend and provider, even if it can never be tamed.

Most of us living in these parts earn our daily bread3 from the sea. My father says that’s because very little of Cornwall is more than a day’s walk from the coast, “so long you don’t turn right and end in Devonshire!”4. These are exciting times, so I’ve decided to keep a diary of all that’s occurring; putting on paper my thoughts and memories and the comings and goings in our village by the waves.

____________

1 Cornwall is the most westerly county in England, with the county of Devon its immediate neighbour to the east. Sticking out into the sea, it has the North Atlantic Ocean on its northern shores and the English Channel on its southern.

2 The French had been traditional enemies and rivals of the English (and Cornish*) for many centuries.

*Many Cornishmen (and women) saw – and see – Cornwall as separate to the rest of England.

3 Not literally bread, of course. Fishing, trading and – in this instance – some rather illegal activities.

4 The next in-land county.

Most of our menfolk are fishermen or work the tin mines5 with the knockers6, but mining is seasonal work, so many miners turn their hands to other things when needs must. Then there are those amongst us who do not belong: the King’s men. These are the redcoats7 and the excisemen8 they support, who work for the Exchequer9. It is their job to make sure that everyone pays the duty – the tax on some of the cargo that comes in by sea. They are about as welcome here as an eel down a trouser-leg, especially as most of them are bullies and thieves and keep for themselves some of what they supposedly ‘rescue’ for the Crown.

My Uncle Jonah explains it this way:

“What should happen to, say, brandy, when it’s brought into the country is that the price of the brandy and the price of transporting should be added together and then a little added on top for the man who sells it, to earn his living.”

No one can argue with that. That’s only fair!

“But no. Rich men and governments like to tax happiness to make it harder for poor men to be as happy as they are. So items which makes people happy, such as that brandy or silks or sot-weed10, aren’t sold that way. No, the Government charges a duty – a tax – on top, when it comes into the country. So the Exchequer’s purse gets fuller than a glutton’s11 corporation12, at the expense of the working man.”

My uncle’s right. ’Tis a proper disgrace, especially when duty is even charged on SALT13, which we all need to eat to stay alive!

“These taxes are called customs and collected at the Customs Houses at the ports and harbours, but it’s a most unfair custom if you ask me! And, to top it all, there’s another tax called excises, collected to pay towards some war or other, long forgot or yet to come!

“Now, this don’t seem fair and proper to some folk, so they try to sneak in such cargo under the noses of the greedy excisemen without them being aware. This way, the poorer folk get to enjoy their pleasures a little cheaper, see? And this is why such folk call themselves free-traders, but the excisemen don’t see it that way. They think of them as common criminals and call ’em smugglers. But condiddling14 it ain’t!”

Uncle Jonah speaks the truth! It’s all very well for them stiff-rumps15, with their high-paid positions and fancy clothes. But what about us? Well, as for me, I’m proud to say I’m a smuggler’s daughter.

By that, I mean my father is a smuggler. My mother was a lady – some might have called her a blue-stocking16– a true and proper lady from a grand family in a grand home, and she taught me the reading and the writing, which few can do in Minnock, ’cept Squire Treppen, the priest, and a handful of officials with self-important titles, strutting around like birds who’ve had their fill of seed. Since she died, me and my sister Esme have been mothered by Eliza, my brother being grown17. Some see Eliza simply as a cinder-garbler18 but she’s acted as everything from housekeeper to friend.

But don’t get me wrong. She’s not all sweetness and light. I once saw her take a belt to her own boy – also a grown man now – and give him a right clapperclawing.19

My father’s name is Jon without the ‘h’, as was his father’s and his father’s before him, all the way back to when Jonah was livin’ in that whale20, or so my namesake uncle Jonah would have it. And by day, that is all that others call him. (No one ever calls my Uncle Jonah ‘Jon’ for short, for that would be far too confusing!)

By night, however, the villagers go by different names and, in all my short life, I have never heard them mix the two. My father’s name by night is ‘Captain’, which shows just where he sits in the order of things: he’s the one to give the orders and none give them to he. He carriers a pair of poppers21, one on each hip, tucked inside his belt, all hid beneath that great long coat of his.

My Uncle Jonah is ‘Patch’, and our nearest neighbour, Robert Treggan, ‘Goose’. The reasons for these names are less clear to me, but the reason for giving them is obvious: should a redcoat or exciseman hear them calling out to each other in the dark, when they are about their less lawful pursuits, their identities will not be revealed!

____________

5 Mining began in Cornwall in the Bronze Age and reached its height in the nineteenth century.

6 Mythical creatures, either pixie-like or souls of dead miners, heard knocking in other parts of the mine. Miners would often leave a small part of their pasty ‘for the knockers’. A Cornish pasty was – and is – cooked meat and vegetables in a folded pastry case. (Once they may have been savoury at one end and sweet at the other, for a complete meal down the tin mine.)

7 Soldiers, who wore bright red uniforms. The whole idea of a uniform back then was to BE SEEN, not to act as camouflage.

8 The excise men were in charge of ‘customs and excise’ – the taxes and tariffs people had to pay when importing certain goods.

9 The Government’s funds.

10 Eighteenth century slang for tobacco. You’ll find Kitty uses a LOT of slang in this diary!

11 Greedy eater.

12 Big, fat tummy.

13 The word salary comes from the Latin word for salt, because Roman soldiers received some of their pay in salt, it was so vital.

14 Stealing (More eighteenth century slang!).

15 Haughty, stuck-up folk.

16 A knowledgeable woman.

17 A grown man: a grown-up.

18 A female servant.

19 Thrashing/beating.

20 A story from the Old Testament of the Bible.

21 Flintlock pistols.

Just got back from my uncle’s cottage over by Hangman’s Cove. There’d be no point in bringing in cargo to Minnock itself, where Mr Duggan, the exciseman with his offices on the harbour over at Fowle, can walk right down to the water’s edge and position his soldiers along the shoreline. No, my father and his companions need to bring in the tax-free, duty-free, excise-free goods into a cove, surrounded by craggy cliffs near impossible to climb down. And which any greedy, snooping exciseman imagines to be too steep and difficult for smugglers to climb up. Little do they know! They are as much in the dark as a blindfolded mole!22

There is a cave down on the beach of Hangman’s Cove, its entrance well-hid by boulders, which has a passageway through the rocks which leads up to the clifftop, by which the smugglers come and go. This be ideal for moving contraband23 by moonlight!

This is very different to Cawsand24, where I hear there are fifty free-trader boats taking regular trips to and from the Continent, as bold as brass and as bright as day!

Today, however, there was nothing to see but a few seals.25 Come breeding-time, they’ll rest up on the beach but today, with winter come, I only glimpsed a few out at sea; their bobbing smooth-grey heads like floating cannonballs. But they looked at me and I looked at them and we each knew that this is where we all belong.

____________

22 Moles aren’t completely blind, of course, just very short-sighted.

23 Goods imported or exported illegally, without the payment of taxes.

24 Cawsand was the regular haunt of well-known smuggler Harry Carter. Customs services reckoned that, in 1804 alone, over 17,000 kegs of spirit were landed there. That’s an average of over 46 kegs a DAY!

25 Grey seals, dolphins, basking sharks and even minke whales can all be seen on certain parts of the Cornish coast.

Hangman’s Cove got its name not from actual gallows where men were hanged. My father says in his grandfather’s day, there were two stone arches jutting out into the water, formed naturally by waves wearing away rock over thousands of years. They’ve long since crumbled and been washed away, leaving nothing but two stone pillars we calls the Stacks.26