11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

Native American culture is founded on stories told orally and handed down through the generations, outlining myths that reveal the origin of a tribe, legends that chronicle heroes who fought the gods, stories that tell of malevolent trickster spirits, and canny morality tales for the ages. In Native American Myths & Legends you can read about characters such as Old Man, Rabbit Boy, Blue Jay (the trickster bird), the Double-Faced Ghost, the Splinter-Foot Girl and Mondawmin, the Corn Spirit. You will also discover the meaning of the Potlatch Feast, the legend of the Great Turtle and the myth of the Bear Foster-Son. The book is divided into seven chapters, covering creation myths; people, family and culture; the natural world; ghosts and spirits; gods, demons and heroes; love, morality and death; and warfare. Illustrated with 180 photographs and artworks, Native American Myths & Legends is an exciting and informative exploration of the beliefs and culture of North America’s first inhabitants.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 289

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

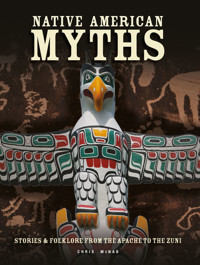

NATIVE AMERICAN MYTHS

NATIVE AMERICAN MYTHS

STORIES AND FOLKLORE FROM THE APACHE TO THE ZUNI

CHRIS McNAB

Copyright © 2018 Amber Books Ltd

Reprinted in 2018

Published by Amber Books Ltd

United House

London N7 9DP

United Kingdom

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Facebook: www.facebook.com/amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

ISBN: 978-1-78274-628-7

Project Editor: Michael Spilling

Designer: Zoe Mellors

Picture Researcher: Terry Forshaw

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1. CREATION AND THE UNIVERSE

2. PEOPLE, FAMILY AND CULTURE

3. THE NATURAL WORLD

4. GHOSTS, SPIRITS AND THE DEAD

5. GODS, MONSTERS AND GREAT BEINGS

6. HUMANITY – LOVE, LIFE, MORALITY AND DEATH

7. WARRIOR RACE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

It is a common bias in the West to describe North American history beginning with the European colonial settlements of the 16th century, which laid the foundations of what would become the modern United States and Canada. Yet these events – a mere 400 years of time – are temporally eclipsed by the history of the indigenous peoples, the Native Americans.

Their story, enacted across the vast tracts of North America, stretches back anywhere from 16,000 to 30,000 years ago, at the point when early humans moved across the Bering land bridge (Beringia) from Siberia into north-west North America. Over the subsequent thousands of years, the new arrivals spread from this icy foothold across the whole of the Americas, establishing tribal territories and local identities as they did so.

ORAL HISTORY

At the moment the first European colonists stepped ashore in North America, therefore, the Native Americans already had their own long history. But that history, and the cultures developed within it, was not codified and recorded in written texts, but instead told in a vibrant tapestry of oral traditions – collections of myths, legends and narratives passed down across centuries. These are true living histories. Each story would be injected with the drama and interpretation of the storyteller, the twists and turns of plot and character energized for a rapt audience gathered around a crackling campfire. At the same time, the storyteller would adhere faithfully to the core details and structure of the narrative, ensuring its accurate transmission across the ages.

A Cherokee mother and daughter make pots of clay on the Qualla Reservation, North Carolina, in this 1880s photograph. Native American myths often feature on craftware.

This book brings together a thematically broad collection of myths and legends from across Native American cultures, from the Tlingit peoples of the frozen north to desert-dwelling Apache. Writing such a work, and collecting and selecting the narratives for inclusion, brings an author face to face with worldviews very different to those that prevail today. In the modern urban context, materialism and individualism generally underpin our philosophical outlooks, however much we try to resist them. We can and do practice spirituality, but this tends to be confined to a specific place of worship, or individual acts of devotion, pools of peace in the midst of hurried lives. Furthermore, as the majority of us live in towns and cities, our perspectives on life are figuratively and literally hemmed in by urbanization, nature overlaid by concrete and tarmac.

This Kiowa shield cover is decorated with a turtle, a thunderbird, stars and the Milky Way.

MAN AND NATURE

Native American mythology, by contrast, is utterly integrated with nature. The myths and legends are bounded only by limitless sky, endless plains, rolling tundra and lush woodlands. Spirits abound, from lonely ghosts up to great Sky Gods and epic monsters, ever present alongside the people who attempt to interact and negotiate with them. The world of humans and nature is seamless and interconnected, animals, plants, even rocks sharing in narratives as equal characters. All aspects of nature are engaged in the physical act of survival and in the diurnal, seasonal and annual rhythms of life. They thus have to find a communicative balance with one another, and the myths and legends told by the Native Americans are often about how that balance is achieved, disrupted or restored.

Yet as we shall see throughout this book, despite their lofty sense of nature and the spirit world, most of the myths and legends are squarely down to earth when it comes to humanity. Many central characters are morally ambiguous, neither fully good nor fully evil, as in life. This is, I would argue, part of the reason why Native American myths are so compelling to a modern readership. They are relevant because they connect with what it means to be human. We can identify with the characters, and therefore find answers to our own life questions.

1 CREATION AND THE UNIVERSE

For those of us who are familiar with the biblical tradition of creation, Native American genesis narratives are a step into the unfamiliar. The Judeo-Christian account of the origins of matter and life sees God creating the Earth and all that lives upon it through an act of divine sanction. It is a simple but powerful model, a magnified version of acts of human creativity, like a builder creating a house.

A dreamlike depiction of an Iroquois creation myth by Ernest Smith in 1936. The Sky Woman falls from her realm down to the world below, the giant turtle receiving her and becoming the foundation for the Earth.

MANY NATIVE American creation accounts do hinge upon a creator being, a figure of universal power who either shapes the world physically or at least guides the direction of its emergence.

THE MASTER OF LIFE (PIMA)

The Pima people of what is now known as southern and central Arizona told of the ‘Master of Life’. Like a craftsman at work, this Master of Life literally sculpted all that the Pima saw around them – rocks, canyons, river valleys, the mesa tablelands, the grasses and flowers, plus all the creatures that flew, swam and crawled there. Only once the Earth was shaped and imbued with its flora and fauna did the Master of Life then reflect upon the need for human beings to complete and manage creation. In a loose parallel with the Genesis narrative, the Master of Life decides to make human beings in his own image, although the creative process is highly manual – the Master literally crafting the humans from a ball of clay and baking it in a cosmological kiln.

A Pima earth lodge, made from wattle and daub with a thick covering of soil. A smoke hole in the centre of the roof would let out the smoke from cooking.

Yet the process of creating human beings would not be straightforward for the Master of Life, for it was subject to the interference of that most wily of characters, the Coyote. While the Master was out collecting wood, the Coyote took the hardening figure from the kiln and remodelled it in the image of a humble dog. When the Master returned, he took the figure from the kiln and breathed life into it, at which point he was confronted by an animate and barking animal. Sensing the culprit, the Master rebuked the Coyote for his manipulation and started again on his quest to create human beings. This time he formed two figures, distinguished by the biological differences that would enable them to reproduce. Back into the kiln they went, but again the Coyote would not do as he was bid. He told the Master that with his keen nose he could smell the figures burning and that they should be removed immediately. The Master did so, but on inspection it was apparent that they were underdone and had pale skin. Anger raged in him, and once again he rebuked the Coyote. But creation could not be undone, and thus the Master breathed life into the figures anyway. These humans did not belong in the lands created by the Master, so he sent them away to another place, far across the sea, and resumed his work from scratch.

THE PROCESS OF CREATING HUMAN BEINGS WOULD NOT BE STRAIGHTFORWARD FOR THE MASTER OF LIFE, FOR IT WAS SUBJECT TO THE INTERFERENCE OF THAT MOST WILY OF CHARACTERS, THE COYOTE.

The next attempt was again frustrated by the Coyote, who this time prevented the Master from removing the figures from the kiln when he judged that they were done. The predictable result was that the humans were over-hardened, and this time their skin turned a pure black. Like the pale-skinned humans before them, these humans did not belong in the Master’s land either, so after they were given life they too were sent to another distant place across the sea.

Petroglyph carvings of animal figures on a rock by the Salt River, Arizona; the Pima lived around Arizona’s Gila and Salt rivers.

And so the Master of Life once more resumed his thwarted quest to produce human beings in his own image, but this time he did not heed the Coyote’s trickster voice, removing the figures from the kiln at the perfect moment when they were a golden copper brown. It was these people who would become the Pima Indians, inhabiting an arid corner of the United States.

Although the Master of Life title might suggest an omnipotent and omniscient God, as the narrative unfolds it becomes clear that comparisons between the Judeo-Christian creator god and the Pima divinity are forced and unnatural. The Master of Life, as with so many of the Native American creator figures, has a core human fallibility, only producing the humans he desired on his fourth attempt, having been gullibly swayed previously by the trickster Coyote. In other myths, we are introduced to creator figures who are capricious, mistaken, angry, inefficient and easily misled. These are not deities who transcend the humanity they create, but rather fully participate in the beauty and fallibility of their creations. This is why, at a base level, the Native American creation myths feel so authentic to the people and the landscape in which they were formed. What is also interesting is how the myth accounts for the diversity of races, acknowledging the presence of wider human society beyond the immediate people of the tribal lands.

IN OTHER MYTHS, WE ARE INTRODUCED TO CREATOR FIGURES WHO ARE CAPRICIOUS, MISTAKEN, ANGRY, INEFFICIENT AND EASILY MISLED.

UNDERWORLD MYTHS

In the first of our creation narratives given above, we see a powerful but flawed figure shaping the world and creatures around him from a blank sheet, bringing form from the formless. Yet in many cases the Native American creation stories explain the existence of the Earth and the tribal world in terms of an emergence from an already present, typically darker place in the continuum of existence. These can perhaps be labelled ‘underworld myths’, for rather like a Greek Hadean epic, the participants of these narratives undergo a struggle in subterranean darkness in order to emerge into the light of the North American landscape.

A modern visual interpretation of the Mandan Native American creation legend; the Mandan people look to ascend the vines that climb up to the world above.

The Four Mounds (Jicarilla Apache)

A haunting version of the underworld myth was told by the Jicarilla Apache, who lived for hundreds of years in a broad territory encompassing the Sangre de Cristo Mountains located in southern Colorado, northern New Mexico and parts of the Great Plains. In their genesis story, at the beginning of time humans lived alongside animals in a dark underworld, the Earth above covered with an endless ocean. In this underworld, the animals had human powers of speech and intelligence, as did the rocks, trees and other features of the natural world. In this place of competing interests, the diurnal creatures – including human beings – wanted more light to illuminate the underworld, while the nocturnal creatures – particularly the bear, owl and panther – preferred to dwell in darkness. To settle matters, the diurnal and nocturnal creatures played a traditional Native American game involving a button and a thimble. They played four times and each time the people won. With each victory, light grew brighter in the east, forcing the nocturnal animals to run away and hide.

A beautiful portrait of a Jicarilla Apache, the tribe whose traditional lands included parts of present-day Colorado, Oklahoma and New Mexico.

THESE TOWERING MOUNTAINS BECAME PLACES WHERE HUMANS FORAGED AND GATHERED, BUT STILL THEY DID NOT REACH THE WORLD ABOVE.

The coming of the light provided enough visibility to reveal a hole in the roof of the underworld, through which the denizens of the dark could see the Earth above. The people decided that they would emerge from the darkness onto the Earth, yet it seemed to be far beyond their reach. To get closer to the surface, they constructed four huge mounds, one at each point of the compass, and each planted with specific types of fruit. The eastern mound was festooned with black-coloured fruits and berries; the western mound featured yellow fruits; in the north, there were variegated fruits; and in south were the blue-coloured fruits.

These towering mountains became places where humans foraged and gathered, but still they did not reach the world above. In an attempt to close the gap, the people at first made a series of ladders from feathers, but even the strongest feathers – those of the eagle – were not able to support their weight. The buffalo stepped forward and offered his horns to create a new ladder, one that was indeed strong enough to bear the humans. (As an incidental part of the myth, the buffalo horns were originally straight, but the weight of the humans climbing upon them twisted them into the curled profiles that we see today.) Now the people tied together the Sun and the Moon with spider silk, and let them up into the sky to give greater life to the surface of the Earth. At the same time, four great storms blew up, each corresponding to the placement and colour of the mounds in the underworld. The storms blew with such ferocity that they rolled back the waters, forming oceans in their appropriate places and exposing the land beneath them for the creatures to walk on.

THE CROW DISCOVERED THAT THE EARTH WAS DRY ENOUGH FOR THE HUMANS TO INHABIT, AND SO THE PEOPLE BEGAN TO POPULATE THE LANDS.

It was the animals that first explored this new world, in so doing acquiring some of their defining physical characteristics. The polecat, for example, took the first step upon the sodden ground, his legs (and therefore those of his species) becoming permanently black from the mud that covered them. The badger, the next to venture up top, also acquired black muddy legs. Both the polecat and the badger returned to the underworld after their adventure, but it was the beaver that stayed at the surface, using his natural skills to build a dam and thereby conserving water for humans to drink.

A Jicarilla Apache camp, including a traditional tipi. The Jicarilla also lived in ‘wickiups’, homes made from from reeds and branches bent into an elliptical framework.

Eventually the crow, flying far and wide, discovered that the Earth was dry enough for the humans to inhabit, and so the people ascended and began to populate the lands. All the Native American tribes spread out, occupying the places that would become their ancestral territories. Notably, however, the Jicarilla Apaches stayed near to the hole from which they had emerged, circling it three times. When the Ruler of Earth became frustrated by their wanderings, he asked them where they wanted to go and they told him ‘The centre of the Earth’. Guided by their desires, the Ruler took them to Taos – located in the north-central desert region of New Mexico – and here they established their home.

Hopi Indian dancers perform a ritual. One particular ritual dance would extend over eight days, and saw the dancers perform while carrying dangerous snakes in their hands and even their mouths.

Ladder Through the Four Worlds (Hopi)

The theme of the creationist ascent from the underworld appears with striking variations in the southwestern corner of the United States. One of the most evocative is that told by the Hopi tribe, who conceived of stratified worlds beneath our own and of a unique journey through them to the surface.

As with the Apache, the Hopi people lived in a dark and oppressive underworld, the lowest of four such places. It was a cave-world, dark, stale and overcrowded, a place of distress and spectral torment. Yet beyond this chthonic imprisonment, there were the higher spirit beings, angelic figures free from such earthly confines. Two of these – the Elder Brother and the Younger Brother – were moved by pity for the human beings suffering in the darkness, and so they punched holes through the three worlds above them and dropped magical seeds down to those below. The seeds implanted themselves in the soil of the cave-world and grew into a strong ladder-like reed-tree, resilient enough to take the weight of the humans. The people, once they discovered the reed-tree through the sense of touch, began to climb it, hoping that they and their families would reach the next world and begin a new life there.

The first people to attain the second world were largely disappointed, as the ‘new’ world was also underground and still dark and unwelcoming. Nevertheless, they feared that it would soon become overcrowded with those coming up after them, so they shook the reed-tree violently and dislodged those below them, after which they pulled up the tree. The people remaining behind in the first cave-world would need to find their own way out.

Time passed for those in the second world, and as they and their livestock procreated and grew in number, the world became just as crowded as the one that they had left. So once again they took the reed-tree and raised it up, pushing its top through a hole into the third world above them. The people once again made their weary ascent until they reached the third world. Here history repeated itself – those who made it shook the reed-tree to dislodge those following them, and then they too pulled the natural ladder up behind them.

It was in the third world that life finally started to improve for the humans. Here it was lighter than in the worlds below, courtesy of the gift of fire given to them by the Elder Brother and the Younger Brother. Society became more ordered and hierarchical, villages more ordered, and kivas – underground chambers used for ritual practices – appeared and came to life with sacred practice. But the period of harmony was not to last. The womenfolk in the third world appear to become almost possessed by the desire to dance, drawn in by the ceremonies practised by the local shamans, who dressed as kachinas (benign spirits). As the women danced and danced they neglected their family and marital duties, bringing about social chaos as a result.

The interior of a Hopi kiva chamber. A small hole dug in the centre of the chamber symbolized the origins of the tribe.

THE SHIELD AND THE MAN WERE THEN HURLED INTO THE EASTERN SKY, BECOMING THE GLOWING SILVERY MOON THAT SHONE DOWN ON THE LANDSCAPE.

Once again it was time to escape to the world above, and the reed-tree was erected to allow the people to begin the now-familiar exodus to the higher realm. This time was different, however. When the people climbed up through the hole, they found themselves on the surface of this Earth, emerging from what is today the Grand Canyon. But this Earth was still in a protean form, black and uninhabited and hostile in nature. The chief requirement was additional light, by which the people could find wood to make fire. Here entered the figure of the Spider-Grandmother, who weaved a luminous web that provided some welcome light. But still more was needed. Now the Coyote, by nature a thief, unwittingly provided the solution as he emerged from the hole, carrying an earthen jar he had stolen. Taking the lid off the jar, all the stars in the skies exploded upwards into the heavens, the sparkling light singeing the Coyote’s beard forever black.

Native American artwork displayed in the Desert View Watchtower, a 21m (70ft) high building constructed on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon in the 1930s to resemble a Pueblo watchtower.

However, the light was still not enough to illuminate the world and the solution to the problem lay in the hands of the people. They fashioned a spectacular shield from buffalo hide and cloth, and imbued it with magical powers through sacred incantations and a young man stood atop. Both the shield and the man were then hurled into the eastern sky, becoming the glowing silvery Moon that shone down on the landscape. Now by the light of the Moon they could see the landscape around them, which was still half-formed. Thus they called upon the great Vulture, who flew low over the Earth and created, through the immense downdraft of his wings, the contours of the world with its mountains and valleys. The Elder Brother and Younger Brother then added the rivers that flowed through it.

A buffalo hide kachina mask; the kachina are spirit beings of the Pueblo people, and wearing an appropriate mask during a specific ritual allowed them to become manifest.

The Earth was now nearly complete, but it remained cold and it needed a source of heat to warm it for the plants to grow and the people and animals to thrive. Once again, the people made a ceremonial shield, this one highly decorated in strident colours (the first shield had mainly black-and-white patterning), and they decorated it with bright features, cornhusks and an abalone shell placed in the centre. Again, a young man stood bravely on top of the shield as it was swung faster and faster in an expanding arc, and then it was released high into the sky, descending over the eastern horizon. After a period of time, the shield and the man arose from the east, blazing bright as the new Sun. The creation was now complete, and the Hopi Indians settled down to their life on the Colorado Plateau, their journey from the underworld finally behind them.

SPIDER-GRANDMOTHER

THE SPIDER-Grandmother, or Spider-Woman, is a powerful and recurrent figure in the mythologies of the American Southwest. She is intimately connected with the act of creation, the webs that she spins often creating the physical fabric of the world, including the formation of solid ground or the bringing of light. The web also represents the interconnectivity of all things, the strands binding nature together in a seamless whole. There is also the sense in which the Spider-Grandmother can act as a guide to the youthful or vulnerable, and as a protector over a tribe. For example, in one Hopi myth the Spider-Grandmother escorts a young man to the realm of the Snake People, guiding him through various and often frightening trials in his quest to discover a beautiful maiden. Eventually he finds himself wrestling one particularly fearsome snake, which the Spider-Grandmother reassures him is actually the maiden. His persistence and the Spider-Grandmother’s advice eventually pays off – he purges the anger from the snake, who eventually turns into a beautiful girl.

An illustration of the Spider-Grandmother – referred to as the ‘wisdom keeper’ – dispensing magical objects to her followers.

ANIMAL NARRATIVES

One particularly sharp contrast between Native American creation myths and those of the Judeo-Christian tradition is the role that mythical animals play in making the world and the people within it. Sometimes the animal’s creative act is incidental, the unintended consequence of an act of trickery, theft or inquisitiveness. Other times the act is brave and selfless, often in a moment of interaction with heavenly beings. But what is apparent from all narratives is how the Native Americans see animal life as indivisible from both the act of creation and also the spiritual identity of humanity itself. Humans and animals do not occupy separate realms in this world, but instead participate in one vast and interactive spiritual enterprise. Essentially this is a pantheistic vision, all of existence united through inherent divine qualities.

The Turtle and the Twins (Seneca)

During the 1880s, American translator and folklorist Jeremiah Curtin created one of the most invaluable repositories of Native American mythology when he collected hours of oral traditions from the Seneca people, who at that time were living on the Cattaraugus reservation in New York State. One of the advantages Curtin had was fluency in the Seneca language, but thankfully for the English-speaking world some of the narratives he collected were translated in the early 20th century by I.W.B. Hewitt, which were then presented in the Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology.

A wooden dish carved into the shape of a swimming beaver. Beavers represent a variety of characteristics in Native American culture, including stubbornness, hard work and heroism.

What follows is one of those narratives, fascinating not only for the temporary but critical role played by the turtle in the creation story, but also for giving us an insight into the creation stories from one of the largest of the five tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy. To preserve as much of the original language and to provide an insight into the Seneca narrators, the 1918 translation is given in full and unedited:

A beautiful representation of the turtle from Zuni Indians, carved from snowflake obsidian stone. Turtles feature in many Native American creation myths.

‘A long time ago human beings lived high up in what is now called heaven. They had a great and illustrious chief. It so happened that this chief’s daughter was taken very ill with a strange affliction. All the people were very anxious as to the outcome of her illness. Every known remedy was tried in an attempt to cure her, but none had any effect.

‘Near the lodge of this chief stood a great tree, which every year bore corn that was used for food. One of the friends of the chief had a dream in which he was advised to tell the chief that in order to cure his daughter he must lay her beside this tree, and that he must have the tree dug up. This advice was carried out to the letter. While the people were at work and the young woman lay there, a young man came along. He was very angry and said: “It is not at all right to destroy this tree. Its fruit is all that we have to live on.” With this remark he gave the young woman who lay there ill a shove with his foot, causing her to fall into the hole that had been dug.

‘Now, that hole opened into this world, which was then all water on which floated waterfowl of many kinds. There was no land at that time. It came to pass that as these waterfowl saw the young woman falling they shouted, “Let us receive her,” whereupon they, or at least some of them, joined their bodies together, and the young woman fell on this platform of bodies. When the waterfowl grew weary they asked, “Who will volunteer to care for this woman?” The great Turtle then took her, and when he got tired of holding her, he in turn asked who would take his place. At last the question arose as to what they should do to provide the woman with a permanent resting place in this world. Finally it was decided to prepare the Earth on which she would live in the future.

An ancient Native American petroglyph of a turtle. Such was the status of the turtle that some Indian tribes referred to North America as ‘Turtle Island’.

‘To do this it was determined that soil from the bottom of the primal sea should be brought up and placed on the broad, firm carapace of the Turtle, where it would increase in size to such an extent that it would accommodate all the creatures that should be produced thereafter. After much discussion the toad was finally persuaded to dive to the bottom of the waters in search of soil. Bravely making the attempt, he succeeded in bringing up soil from the depths of the sea. This was carefully spread over the carapace of the Turtle, and at once both began to grow in size and depth.

‘After the young woman recovered from the illness from which she suffered when she was cast down from the upper world, she built herself a shelter in which she lived quite contentedly. In the course of time she brought forth a baby girl who grew rapidly in size and intelligence. When the daughter had grown to young womanhood, the mother and she were accustomed to go out to dig wild potatoes. Her mother had said to her that in doing this she must face the West at all times. Before long the young daughter gave signs that she was about to become a mother. Her mother reproved her, saying that she had violated the injunction not to face the east, as her condition showed that she had faced the wrong way while digging potatoes. It is said that the breath of the West Wind had entered her person, causing conception. When the days of her delivery were at hand, she overheard twins within her body in a hot debate as to which should be born first and as to the proper place of exit, one declaring that he was going to emerge through the armpit of his mother, the other saying that he would emerge in the natural way. The first one born, who was of a reddish color, was called Othagwenda; that is, Flint. The other, who was light in color, was called Djuskaha; that is, the Little Sprout.

A horned toad figure etched into a shell with acid, the image formed by a Southwestern Native American artist around 700–900 AD.

‘The Grandmother of the twins liked Djuskaha and hated the other, so they cast Othagwenda into a hollow tree some distance from the lodge. The boy that remained in the lodge grew very rapidly, and soon was able to make himself bows and arrows and to go out to hunt. For several days he returned home without his bow and arrows. At last he was asked why he had to have a new bow and arrows every morning. He replied that there was a young boy in a hollow tree in the neighbourhood who used them. The Grandmother inquired where the tree stood and he told her, whereupon they went there and brought the other boy home again.

IT IS SAID THAT THE BREATH OF THE WEST WIND HAD ENTERED HER PERSON, CAUSING CONCEPTION.

HE SHOOK VIOLENTLY THE VARIOUS ANIMALS – THE BEARS, DEER AND TURKEYS – CAUSING THEM TO BECOME SMALL.

‘When the boys had grown to man’s estate, they decided that it was necessary for them to increase the size of their island, so they agreed to start out together, afterward separating to create forests and lakes and other things. They parted as agreed, Othagwenda going westward and Djuskaha eastward. In the course of time, on returning they met in their shelter or lodge at night, then agreeing to go the next day to see what each had made. First they went west to see what Othagwenda had made. It was found that he had made the country all rocks and full of ledges, and also a mosquito that was very large. Djuskaha asked the mosquito to run in order that he might see whether the insect could fight. The mosquito ran, and sticking his bill through a sapling he fell, at which Djuskaha said, “That will not be right, for you would kill the people who are about to come.” So seizing him, he rubbed him down in his hands, causing him to become very small; then he blew on the mosquito, whereupon he flew away. He also modified some of the other animals that his brother had made.

‘After returning to their lodge, they agreed to go the next day to see what Djuskaha had fashioned. On visiting the east the next day, they found that Djuskaha had made a large number of animals which were so fat that they could hardly move; that he had made the sugar-maple trees to drop syrup; that he had made the sycamore tree to bear fine fruit; that the rivers were so formed that half the water flowed upstream and the other half downstream. Then the reddish-colored brother, Othagwenda, was greatly displeased with what his brother had made, saying that the people who were about to come would live too easily and be too happy. So he shook violently the various animals – the bears, deer and turkeys – causing them to become small at once, a characteristic which attached itself to their descendants. He also caused the sugar-maple to drop sweetened water only, and the fruit of the sycamore to become small and useless; and lastly he caused the water of the rivers to flow in only one direction, because the original plan would make it too easy for the human beings who were about to come to navigate the streams. The inspection of each other’s work resulted in a deadly disagreement between the brothers, who finally came to blows, and Othagwenda was killed in the fierce struggle.’

The Seneca chief Red Jacket (c. 1750–1830). Red Jacket was renowned for his oratory and negotiation skills, the latter used particularly in the land settlements after the American Civil War.

This creation myth is fascinating on many levels. Although the descendants of the Great Chief have heavenly origins, they come across as thoroughly human and fallible in their appetites, prejudices and interrelations. Division and disobedience characterize their early society, leading to expulsion, segregation and ultimately the violent murder of Othagwenda. Such precarious relations are common in Native American mythology; when bound within a creation story, they humanize the narrative of how the world came into being. Yet in many ways at the heart of the story is the turtle, who comes to bear the fabric of Earth itself upon his back, the semi-divine humans performing the minor acts of creation upon his supporting frame. To create the structure, however, the turtle needs the assistance of other members of the animal kingdom, and in particular the toad that dives down into the sea to retrieve the mud from which the world’s surface is fashioned.