9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

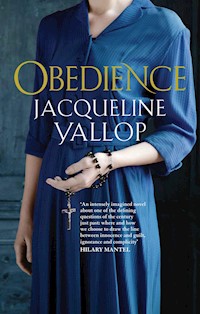

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Sister Bernard has lived in a grey-stone convent in rural France for more than seventy years. In that time, a once youthful and lively cloister has gradually emptied, until only Bernard and two other nuns remain. Now, the three women pack away their few possessions into wooden boxes, preparing to leave the building that has been their home for decades. For the nuns, the closing of the convent means more than losing a home; the walls have shielded them from a changing modern world, for Sister Bernard the quiet monotony of the religious life has protected her from memories of the past - the disgrace of when she was a young woman in wartime France; when her devotion to God faded in the face of her need for a young Nazi soldier; and when she experienced the full horror and violence of war.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

OBEDIENCE

Jacqueline Yallop read English at Oxford and did her PhD in nineteenth-century literature at the University of Sheffield. She has worked as the curator of the Ruskin Collection in Sheffield and is the author of the non-fiction work Magpies, Squirrels and Thieves and the novel Kissing Alice. She currently lives in France.

OBEDIENCE

Jacqueline Yallop

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © 2011 by Jacqueline Yallop

The moral right of Jacqueline Yallop to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback: 978 0 85789 101 3 Trade Paperback: 978 0 85789 102 0 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85789 575 2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

Table of Content

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

For Mum and Dad

OBEDIENCE

One

Mother Catherine knew the devil. He was twisted and dwarfish; his clawed hands were gnarled. His neck was short and his legs bowed. He had a hump on his back, heavy like a sack of walnuts. He was crafty, she knew that; she had heard how cunning he could be. But surely he could never stretch over five shelves of jars, pickles and conserves to take down the coffee and tempt her nuns?

Sister Bernard, too, was a little under five foot tall, and of limited reach. She had to ask for help to take the packet down from its place at the top of the pantry, and this is how she met the young soldier. He stretched over her. She noticed how thin he was. As he reached up, his uniform jacket swung away from his shoulders, too large and loose for his frame, making him gawky, cartoonish. He smelt of damp cloth. He brushed the packet quickly with his open hand, in case there was dust perhaps, and he gave the coffee to Sister Bernard without looking at her. Then he went back to join the other soldiers bent over the refectory table and she listened to their guttural chatter as she lit the stove. She understood nothing. The smell of the coffee made her hungry and light-headed.

Looking out through the small window above the sink there was just the sweep of the convent drive and the village clustered beyond, cramped and low, the moss thick on the heavy stone roof tiles. The wash house, the well and the water fountain huddled together in the dip of land by the stream; the church tower stood high to one side, its spire uncertainly modelled against the trees, and the square in front of it hidden from Sister Bernard’s view. Smoke rose in the cluster of stores and farm buildings packed in by the bakers, hanging in the airless day, misting the street. A dog ran. Women bent low over buckets and baskets, the ridged earth encircling them, their hats pale. On the slope that rose behind the houses, the new leaves of the vines shone and the gnarled old stems greened with the promise of early summer.

Sister Bernard hardly saw it. It was too ordinary, the way it had always been. She could not see that the occupation had made much difference. For the few weeks the German soldiers had been there, the days had passed unremarkably. The women and the old men seemed to be getting everything done. There was a silence settling, an unstirring quiet that perhaps stretched across the whole of this part of France, creasing up against the mountains to the south and north, and unfolding over the flat land on either side. But Bernard hardly noticed this, and God did not mention it.

She stirred the coffee in the pan, watching its thickness bubble. It had been many months since she had tasted coffee; it might have been years, she could not remember. This same packet had been stored on the top shelf of the pantry since long before the previous winter, she was sure of that at least. There was the rationing brought about somehow by the war, which had reached them finally, stripping the shelves at the alimentation in the village. And there was Mother Catherine’s unshakeable belief that coffee was a temptation from the devil. Both of these things had kept it from her, and she had not once thought of the pleasure of it until now.

Sister Bernard carefully folded the packet again, slipping a pin through to hold the loose paper. Then she dipped her finger very slowly into the pan, feeling the warmth of the steam on her hand and letting her finger linger in the coffee until she could not bear it any longer. When she put it to her mouth, she closed her eyes and felt a drip slide down her chin. It was the coolness of her lips she tasted, more than anything.

It was a surprise when one of the Germans spoke, in French, so that Bernard could understand him. She opened her eyes with a start and popped her finger from her closed lips. She could not think what he might want. Even at thirty, in her prime, she was not beautiful. Her hair was already thin and her skin faded, her hands were wretched. No one spoke to her much, except God.

‘Come in, Sister, we will not disturb you,’ said the German.

Bernard half-turned from the brewing coffee, beginning to smile. She twisted her wet finger in the folds of her habit and she tried to quieten the monotone rumble of God preaching in her head. She stepped through the doorway to the refectory where the soldiers were waiting. It was like somewhere new, the sun coming in through the long windows and the table shrunk by the bulk of the men, their uniforms somehow exotic and the temptation still tingling on her tongue. Bernard gulped down a stuttered breath.

But he had not been speaking to her. They were all looking towards the back door, where Sister Jean had paused at the sight of them, unsure.

‘Entrez, entrez,’ he said again, his accent sharp.

‘I have come for the pig scraps, monsieur,’ she said, blinking at the unfamiliar need to explain her routine.

He got up and went to the door, pulling it more fully open and standing to one side, his arm outstretched into the refectory, inviting in the nun. He bowed, low and loose, grinning. One or two of the other soldiers applauded. Still Sister Jean stood outside.

‘Come on then, come on,’ he said again.

Sister Jean did not move. The German looked at her for a moment, no longer smiling, and shook his head. He stepped towards her and pulled at her arm, yanking her across the threshold. She stumbled. He slammed the door behind her and brushed his hands together, ignoring her now as he went back to his place at the table. Sister Jean winced, the idea of pain keeping her bent over for a moment. And then she passed through to the kitchen, her steps hurried and her eyes fixed on the floor, the empty sack slumped behind her like old skin. The soldier whistled quietly and somebody laughed.

‘What are they doing?’ Sister Jean stood close to Bernard and piled the leftovers from the bucket into the sack. It swelled on the floor between them. She watched exactly what she was doing, did not even glance at the men.

‘They’re having coffee, Sister. They’re waiting for someone who is with Mother Catherine; it’s their commandant, I think.’ Bernard was embarrassed by the hiss of Jean’s question. ‘They’ve been very quiet – they’ve been no trouble.’

Sister Jean pulled tight the neck of the sack and kicked the bucket back towards the sink. It was noisy on the stone floor.

‘They’re drawing straws.’

Bernard could not see how she had known this. There was hardly a movement between the soldiers.

‘Pigs,’ spat Sister Jean, dragging the sack out into the refectory again. The men did not stir this time as she passed.

Bernard took the pan from the heat. The handle was insecure and her hand unsteady, and she walked slowly with it far in front of her as she took the coffee to them. Two of the soldiers parted, pushing back so that she could fill their glasses, and Bernard held the pan high over the table between them before pouring a measure evenly into each glass. She did not spill anything. Some of them thanked her, and though her hand trembled, God was silent.

Later, when the Germans were preparing to leave, the soldier who had helped Bernard with the coffee brought his empty glass to the sink where she was scraping carrots. He stood for a moment at her side, and she paused in her work. She turned towards him; she saw how young he was, perhaps only twenty, and she saw the perfect blueness of his eyes, an intimation of divinity. Smiling, he pulled her veil back from her face, as though to take a better look, and then he leant towards her and whispered something softly in her ear in German. She did not understand what he said, but she blushed anyway, surprised at the intimacy of the coffee on his breath. As he left her, he tossed away the short end of matchstick; one of the other soldiers nudged him.

Smoke hung low from the house fires and the air was thick. The shutters were closed tightly, blinding the rough walls, the warm ochre of the stone faded in the grey light. The clumps of iris pressing against the buildings and along the edges of the street seemed pallid, their reds and purples already exhausted. The shuffle of the village could have been silence, and when the two German soldiers passed the wash house their shoes clicked incongruously on the cobbles, the abrupt echoes spiking the quiet. The nuns were folding heavy wet cloths into baskets; they did not look up. Bernard was rinsing down the long rows of stone basins, each one split open like a giant missal so that the linen could be scrubbed against its sloping surfaces. Unthinking, she watched the dribble of sudded water disappear into the unmoving depths of the central wash pond, and she heard the tap of the soldiers’ footsteps as a counterpoint to the grumble of God. She lifted her head, the heavy bucket hanging still for a moment, as she watched the Germans go round the corner towards the church.

Her soldier followed, alone. He paused in front of the wash house, stepping carefully to one side to avoid the puddle of spilt water leaking away towards the stream. He wished the nuns good morning, his French careful and studded with accent. One of the sisters with the basket of washing, a pretty young girl, returned his greeting, half under her breath, dropping her eyes. The soldier looked at the nuns in turn, as though weighing something up. He came to Bernard last. She was half-hidden in the gloom of the interior, the slouch of her habit making her shape indistinct. She met his gaze for a moment, the water dripping fast onto the dark fabric. She saw him clearly, even in that instant, the slightness of him soft in the smoky damp, his hands held tight in front of him, his face already anciently known to her. She looked at the way he stood, at the defeated slump of his shoulders, and she knew she had been chosen for something.

For the rest of the day and into the night Sister Bernard thought about what this might be. She went through events, tremulous and expectant, ignoring as best she could the incessant complaints that God hammered into her head. She recalled everything about the soldier; she went over and over his incomprehensible code of broken-nailed hand signals and half-obscured facial gestures. The thought of him was irresistible, a mystery. It made her feel beautiful. And, while it lasted, it gave her a glimpse of paradise.

The following morning, weary, Bernard sat for a moment on the flat wall that ran out to the henhouse. The sun was low behind the convent, trapping her in shadow. She dipped her head into her hands, and her veil fell thickly about her. She sat very still, doing nothing. God railed.

Since she was a girl, for every waking minute of every day and throughout her dreams, Sister Bernard had been pestered by the voice of God. He commented on everything she did, from the most intimate of habits to the most routine of chores. He was often taxing and abusive, always uncompromising. He disliked sloppiness, and was particular about clean shoes, stockings without holes, and the quantity of toothpaste squeezed onto the brush. His vengeance was swift and loud and stupefying. In the terror of it, her head would fill with the roar of Him until her eyes smarted. Only many hours later would a note of birdsong or the purr of a car engine creep back to her, wary. She could never hear her own voice above the din.

‘Sister Bernard?’

There was no sign that she had heard. The other nun leant forwards and gently touched the sway of her veil.

‘Sister Bernard?’

Bernard lifted her head this time, blinking. She was surprised that the soldier was not there. She was not sure where she was. All she could be sure of was the smell of cut grass and frying garlic, and she put her hand to her mouth.

‘Are you quite well?’ The other nun leant forwards, her words slow. ‘The girl is here – Severine.’

The woman was of Bernard’s age. She held a bundle of baby and stared at Bernard from behind the other nun, her face stupid and blank. Bernard concentrated for a moment on the rise and fall of her nausea; she stood, shaking herself.

‘Yes. Thank you,’ she said, frowning at the way things were settling back to normal.

‘I’ll leave you then, shall I? For a moment.’ The nun smiled. ‘I’ll leave you,’ she said again.

It was against the rules. Given over to God, the nuns were supposed to have forgotten their families and their friends in the greater vocation of religious life. Earthly ties should have been broken. But there had been no way of keeping Severine from Bernard. She had come silently and irregularly, waiting for long hours on the convent steps or by the kitchen door. They had tried explaining things to her, or shouting; they had shooed her away with the stray cats and once Mother Catherine had brought a great flat dish of holy water to fling at her, an exorcism. But she had always come back, waiting for Bernard without a sound.

Bernard went slowly to Severine and kissed her in greeting, stepping beyond the shadow to where the grass lay in the sun.

‘Come on.’

Severine looked long at the nun, expressionless. Then she held out her hand and Bernard took it. They went together up along the wall. Swallows looped out of the open-sided barn, cutting across the dark beams where the last trusses of onions were hung. A pair of fat ducks limped into the shade of the spreading fig tree. Where the path narrowed, the two women dropped hands, waddling instead in single file, their clogs clicking out of time as they slowly followed the track past the pigsties to the far vegetable garden. Lines of sticks cast criss-cross patterns on the flat earth. Shoots pressed upwards in exact rows. God’s complaints were muted here, unalarming.

They looked down at the baby. Its head was small and its skin yellow, the lines around its mouth unfinished. It did not open its eyes.

‘I have brought you something, Sister,’ Severine said quietly, her words careful. She shifted the baby onto one arm and reached into a pocket. When she held it out to Bernard her face was too expectant. ‘I saved it for you, this time.’

It was the baby’s umbilical cord, shrivelled now and dried out, twisted and brown, like a shaving of something.

‘For luck,’ she said, shifting the weight of the baby again. Bernard took the cord carefully and turned it over in her hand.

‘It’s kind,’ she said.

The baby stirred. Bernard watched as Severine pushed her finger at its mouth, quietening it. But when Severine began a moment later to unbutton the front of her blouse, Bernard turned away. She did not see the baby pushed against her friend’s breast, its mouth slack on the red nipple. She looked out instead to where the white cattle were grazing, and she put the present into her pocket, letting it fall deep inside, feeling it, a talisman.

‘You’re well?’ Bernard asked, still turned away. ‘You’re all well?’

There was no reply for a long while.

‘Oh, he won’t…’ Severine said at last. ‘He never,’ she added, defeated.

Bernard heard the rustle of clothing. She turned back; the baby was lying flat again across Severine’s arms.

‘Busy – busy at the farm.’ Severine looked hard at her baby, pulling it close. In the brightening light, Bernard noticed new patterns of lines creased into her friend’s face, the girl she had always known disappearing. ‘Couldn’t come here, with it all. When there’s no men. Couldn’t come.’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ Bernard said.

‘No.’

Bernard thought about the soldier. ‘Have you seen the Germans?’

Severine nodded.

‘Have they come to the farm?’

‘No – not yet. It’s too far. Too dirty.’ Severine grinned. ‘Don’t like the mud, do they? It keeps them away. Lets us get on with things, doesn’t it?’

She seemed to want a particular kind of answer.

Bernard shrugged. ‘They come here sometimes,’ she said. ‘They come to the convent.’

She wanted to say more; she thought she could find a way of describing her soldier. But Severine stepped across and put her hand firmly on Bernard’s arm.

‘I see you in church,’ she said. ‘On Sundays. Every Sunday. I wait for it.’

This did not seem new. Bernard hardly noticed what her friend had said; she did not see the way Severine’s gaze seemed fixed on her, pleading.

‘I suppose,’ she said vaguely, not knowing how to begin again, the thought of him so pungent.

Their lives had always been the same, commonplace and familiar, known to them both without thought. It was too hard now to find the things to say. The war had somehow crept upon them, tangling them in change, confusing and disorientating them. Everything looked as it had always done. The new vegetables pushed through the dry layer of bronze soil; the animals shuffled across the yard, unhurried. In the clump of trees beyond the wall, the song of a nightingale trembled and tumbled, remembered from years past, filling the air with the sound of old summers. But still nothing was quite settled. There was a new strangeness to things, as though everything was a little brighter, sharper, louder. They had secrets, for the first time, and no way of telling them. So they stood together quietly at the edge of the ridged garden and the baby made soft noises. They bent their heads in the sun.

When the clock struck, Severine started.

‘Have to go,’ she said. ‘Can’t stay.’

Bernard nodded. ‘I’m pleased you came. Thank you.’

She watched her friend pick her way along the path and down towards the village. God was scathing about the idiot girl who had always followed Bernard around, the ugly bent-backed peasant. But Severine had always been in Bernard’s life, constant and unobtrusive, something of a blessing, and Bernard felt the tug of momentary loss as she disappeared in the dip of the land. She put her hand in her pocket and closed her fingers around the tough string of the umbilical cord. No one had ever given her such a thing before.

Over the following three days, the soldier met Bernard twice at the wash house, once in the open street and once in the convent corridor. Once she glimpsed him briefly at the top of the narrow stone steps that led down to the village well, three of his comrades alongside him and a line of cattle ambling down towards the long troughs, their tails heavy in the air. But by the time she had scrambled down the hill, slipping on the new grass, there was just an old farmer swinging his stick at the last of the cows, his beret pulled low over his brow and a torn sack slung across his shoulders as some kind of coat. The soldiers seemed to have disappeared, as though they had never been there. The farmer nodded at Bernard and moved on. Bernard looked around at the green snarl of hedges, the empty shadows of the sunken well and the closed houses at the edge of the village, and wondered for a moment if the soldiers and their war were nothing more than a mistake of hers, a bizarre dream conjured by her prayers, a mystical, unfathomable story like the ones they taught her at the convent.

But there were times when he took her hand, making everything suddenly real. The touch of him was unmistakable. When he reached towards her, Bernard could hear her heart pummel the woollen vest beneath her habit, and God was silent. It seemed miraculous. It astounded her that merely the sight of the soldier could somehow put an end to His ill-tempered prattle. Even the anticipation made Bernard’s breath come quickly and in the ecstatic hours of the night, with God droning in her head, the thought heaved within her, making her hot and unsettled, flushing her cheeks with sudden excitement. By the end of the week, she could no longer still the tremble that was lodged around her heart and when she saw him turn the bend in the convent corridor, she found the rapturous words of the Gloria coming full chorus into her head as the clamour of God receded. She stopped, amazed that the skinny German could do this.

‘Do you want to have sex with me, Sister Bernard?’ he asked in French, in a low tone. It was a phrase that had been easy to perfect with a little practice, and his accent was good. Bernard had no difficulty in understanding him.

She could not look at him, she could not think of a reply. The sense of things shrank away from her. Not wanting to be delayed, the soldier put his request again, raising Bernard’s chin with his forefinger so that she was forced to look at his smile.

‘You know my name,’ said Bernard at last, trying to swallow the panic of her delight.

‘Yes.’ He did not want to be tempted into trying out phrases he had not practised.

They both heard footsteps, further along the corridor; the soldier instinctively moved several paces away. Two nuns passed them, one fingering her rosary. Bernard could not be sure who they were; everything seemed unfamiliar, distorted. It could have been a reflection, warped somehow.

When the nuns had gone, he spoke urgently, with authority, knowing that he had a deadline looming.

‘You will come tonight at ten to the top henhouse.’

‘Oh no – it’s too late.’ Bernard pulled at the end of her veil with a frantic hand. ‘We can’t leave our cells at that time.’

The soldier sighed and Bernard felt the strange ache of disappointing him.

‘You will not come?’ Reworking the plan and afterwards learning the phrases to communicate it would mean an inevitable delay. He risked failing, and he had a sense of what the rest of the unit would say about him then and of how they would exclude him. He stepped towards Bernard. ‘You must come.’

She shook her head. The colour had left her cheeks now.

There was the click of shoes on the tiles, and two more Germans strode briskly along the corridor, seeming to fill it, smiling broadly at the soldier from a distance.

‘You must come,’ he said again.

She fidgeted under his fierce gaze. ‘I don’t… I can’t.’

One of the other Germans spoke, pushing forwards so that he was close to her, stocky and immovable.

‘What do you think of him, Sister? What do you think of Schwanz?’

She was confused by the press of them around her, their unfamiliar smells pungent and their faces too large. But she caught the soldier’s name, and she looked at him again, seeming to know him.

‘That’s… that’s your—’

‘Schwanz. He is Schwanz – that’s his name,’ the other German answered her, smiling. ‘And he really wants to meet with you, Sister.’

Bernard hesitated. The young soldier dipped his head, no longer looking at her, and the other two Germans grinned. When one of the nuns rounded the corner of the corridor and saw Sister Bernard looking up, wide-eyed, at the lanky soldier between his comrades she felt that something might be amiss. She came up and slipped an arm around Bernard’s waist, above the belt of her habit. There was a moment’s vacancy; then the soldiers bowed together in brief salute and left.

The nun dropped her arm.

‘He knew my name,’ said Bernard very quietly, the marvel of it rooting in her.

‘Is that all, Sister? Did they want something?’

Bernard hardly remembered. She would never think about the soldier’s request or its implications. She shook her head.

‘You should direct these soldiers to Mother Catherine. They should not be alone here,’ said the nun. She looked hard at Bernard, trying to make her words penetrate.

Bernard shook her head again. She could hear God coming back to her, protesting at a distance, and afterwards the bell for prayers. But nothing would quite settle and she did not know where she was.

Several days later, he tried again.

‘You can meet me in church,’ he said when he caught Bernard on the way to the woodshed with a bundle of kindling. The sun was hot already, sliding off the redtiled roofs of the outbuildings and bouncing back from the mottled stones. He wiped his sleeve hard across his forehead, unused to the southern heat. ‘Tonight. I will wait.’

Bernard could not think of a reason why she should go to church alone.

‘I will arrange it,’ was all he said, remembering to smile.

Bernard shuffled in front of him for the few yards to the lane. She puffed under the weight of the sticks. She expected him to laugh at how her feet turned out when she walked, the way the village children did, but he was silent and she took his reticence as a kindness.

Something was done and Bernard was told by Mother Catherine to collect the altar silver from the church for cleaning. She was given the key to the cupboard in the sacristy and told that she could be excused evening prayers if her errand took time. How this came about, she did not know. But on the way to the church in the late spring dusk she could hardly stop herself from running. The light seemed sharp around her, making everything crisp and memorable and somehow new. The sky bent to her, expectant, and even God could not muffle the melodies of the world. When she pushed open the leather door into the dim nave, she expected something glorious to happen. She would not have been surprised by choirs of golden angels.

The soldier was sitting in the pew furthest from the altar. His head was bowed; he might have been praying. Even with the thud of the door as it swung back, he did not move. Bernard stood at the far end of the aisle and waited. The church was unlit and the evening was darker there than it was outside, the smell of winter still trapped within. The arches of the roof stretched away into shadow; the side chapels were nothing but dark. Bernard shivered. She had never learnt to be comfortable here.

When he finally turned to her, his face was white in the gloom. Without speaking he left the pew and walked along the back of the church to where some old benches were pushed in against the pillars, creating an extra block of seating out of sight of the altar. It was hardly used; the benches were untidy. He pushed the back two or three more neatly into rows, the scrape of them sharp on the flagged floor, then he spread his pocket handkerchief across the wooden seating and looked at Bernard, for the first time.

The wager was safely settled. Bernard had her hips jammed uncomfortably against the bench and kept up an animal whimpering that echoed in the cavern of the side chapel, but the German soldier was efficient and intense; he let nothing distract him, not even the unremitting flap of his uniform jacket. For a moment afterwards he held his head in his hands, but as Bernard sat up, dazed, he straightened himself. He folded the handkerchief evenly. When he left, his footsteps loud, he did not look back at the immensity of the church behind him.

God returned to scold as soon as she was alone. His wrath was tangled; He pointed out the scuffs on her shoes and the slight filmy drip on the floor where she stood, but He had no words for what she had done. Stretching out the soreness in her joints, Bernard went through to the sacristy in the confusion of His disapproval. Trying to open the cupboard she dropped the key and had to kneel in the almost-dark to search for it among the books and boxes piled on the floor. She could not move quickly. It was a long time before her thick fingers found what they were looking for, and even then she stood for a long while looking at the cupboard door before she tried to open it again. The state of the sacred silverware within threw God into a paroxysm of rage.

Two

The old war was there in the stones of the village, in the unnecessarily neat walls built by the prisoners and in the hidden corners where the blood of murdered soldiers had once flowed. But it was more or less invisible in a new century. Music drifted up from the old charcuterie, transformed now into a bar, with bright lights and a pool table and a succession of boys on noisy scooters; there was nothing left of the hung hams and the wooden counter piled high with flecked saucisson and boudin. Even the wide window had been pulled out and altered; the old flagged floor concreted over. In the years after the war, when the shop had been empty, there had still been a smell there, the rich odour of drying meat. But that, too, had finally gone and now there was only the tinny repetition of songs in strange languages. Bernard stretched through the open window and pulled the convent shutters tight. The sound of the music faded; she had it almost shut out.

She continued purposefully, closing each set of shutters, not pausing in any of the empty cells, her progress steady and unhurried, the fall of the heavy dusk already a defeat. The processional squeal of the hinges filled the long corridor. She paused for a moment, while her breathing settled, and she offered something, the hint of a prayer, in return for a brief balm for some of her pains. She had never thought it would be like this, to be old. She had never imagined the inescapable monotony of her decrepitude. She raised her eyes to the convent ceiling, where long trails of damp cobwebs darkened the pocked plaster, and she sighed.

At seven she rang the gong, as she always did, its tones weaker now than they once were. Then she went to fetch Sister Marie and Sister Thérèse who would not have heard it. They were sitting where she had left them, in the little snug fashioned from a corner of the groundfloor passage. When the convent had been busy, this had been something of a bottleneck, an awkward crick in the smooth running of things, where the nuns were apt to bump into each other with their bundles of firewood or bed linen, and where the sound seemed to gather, drawing in the grumble of things all around. Now, with just the three of them remaining, it was the only space small enough to seem habitable, a retreat from the cold wide rooms in the rest of the building, a corner of comfortable armchairs and a heavy television. It was where they spent most of their time. It was possible to imagine here that they were filling things, keeping the emptiness of the convent at bay.

A faded blue and white Virgin gazed out placidly over their heads from her niche and the faint perfume of chrysanthemums drifted up from the burnt-orange bouquet at her feet. Sister Marie smiled at Bernard, too lavish a greeting, and Sister Thérèse put down her sewing with a sigh.

‘Supper?’ said Thérèse.

Bernard nodded. She leant forwards and rearranged the sloping wimple on Marie’s head. Stepping back, she noticed a fallen chrysanthemum petal and she bent to pick it up, the gathered age in her bones breathing a slight moan. She could not think of anything to say; there was a response to everything that was happening, she guessed that, but it would not come to her. Nor, she knew, could it be shouted into the depths of Thérèse’s deafness, histrionic. So she put the petal in her pocket and pulled herself straight, her face unchanging.

‘Supper,’ she said quietly.

Thérèse saw the familiar flap of the word. ‘It’s been a fine day, Sister Bernard,’ she said, nudging herself out of her chair. She took Marie’s right arm.

‘It’s going to rain,’ said Bernard, taking Marie’s left arm.

They pulled. Marie swayed gracefully upright until, her knees still half-bent, she was balanced against the strain exerted by Bernard and Thérèse, a masterful demonstration of a physical law none of them would ever know. They hung there for a moment, the three of them, old women playing ring-a-ring o’ roses, and then, with a final tug, they brought Marie to a stand. She swayed precariously.

‘That’ll kill me one day,’ said Thérèse. She did not mean it. She felt strong. She still had the straight limbs of youth that made her seem tall, a firm face drawn tight around her sharp nose, and smooth hair that could not quite be called grey.

‘God sees our pain, Sister,’ said Bernard, beginning to edge Marie along the corridor.

The refectory exuded the damp chill of breathing stone. The light through the long windows was flaccid, and the stained plaster browning the ceiling and the tops of the walls was somehow an accusation. At the far end of the heavy table two high-backed chairs were set close to each other, draped across with the peeled skins of wet stockings.