11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

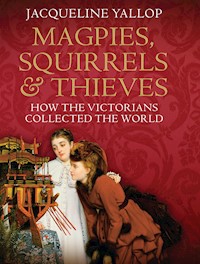

During the Victorian age, British collectors were among the most active, passionate and eccentric in the world. Magpies, Squirrels and Thieves tells the stories of some of the nineteenth century's most intriguing collectors following their perilous journeys across the globe in the hunt for rare and beautiful objects. From art connoisseur John Charles Robinson, to the aristocratic scholar Charlotte Schreiber, who ransacked Europe for treasure, and from London's fashionable Pre-Raphaelite circle to pioneering Orientalists in Beijing, Jacqueline Yallop plunges us into the cut-throat world of the Victorian mania for collecting.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

MAGPIES, SQUIRRELS & THIEVES

MAGPIES, SQUIRRELS & THIEVES

HOW THE VICTORIANS COLLECTED THE WORLD

JACQUELINE YALLOP

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © 2011 by Jacqueline Yallop

The moral right of Jacqueline Yallop to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84354 750 1

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85789 561 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

‘Things’ were, of course, the sum of the world.

Henry James, The Spoils of Poynton, 1897

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

Catching the Collecting Bug

1 Exhibition Road, London, 1862

2 The Useful and the Beautiful

3 A Public Duty and a Private Preoccupation

Making Museums: Collecting as a Career JOHN CHARLES ROBINSON

4 On the Banks of the Seine

5 The Battle of South Kensington

6 The Tricks of the Trade

7 Changing Times

Ransacking and Revolution: The European Crusade CHARLOTTE SCHREIBER

8 Mrs Schreiber’s Big Red Bag

9 Pushing and Panting and Pinching their Way

10 The Gourd-shaped Bottle Gourd-shaped

Pride, Passion and Loss: Collecting for Love JOSEPH MAYER

11 Waiting for the Rain to Stop

12 Mummies, Crocodiles and Shoes for a Queen

13 The Treasures of the North

14 A Larger World

Fashion, Fine Dining and Forgeries: Dealing in Society MURRAY MARKS

15 Rossetti’s Peacock

16 A Notorious Squabble

17 The Fake Flora

Collecting the Empire: In Pursuit of the Exotic STEPHEN WOOTTON BUSHELL

18 The Route to Peking

19 The Promise of the East

20 Collecting Without Boundaries

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

List of Illustrations

1. The South Court at the South Kensington Museum. Illustrated London News (6 December 1862). © Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans.

2. Portrait of John Charles Robinson by J. J. Napier. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

3. Robinson’s collection at Newton Manor. © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

4. Portrait of Charlotte Schreiber by George Frederic Watts. From Charlotte Schreiber’s Journals: confidences of a collector of ceramics and antiques throughout Britain, France, Holland, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Austria and Germany from the year 1869–1885 (1911).

5. Portrait of Charles Schreiber by George Frederic Watts. From Charlotte Schreiber’s Journals: confidences of a collector of ceramics and antiques throughout Britain, France, Holland, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Austria and Germany from the year 1869–1885 (1911).

6. Gourd-shaped bottle. Courtesy of Sotheby’s Picture Library.

7. Portrait of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Theodore Watts-Dunton by Henry Treffry Dunn. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

8. The Peacock Room. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1904.61.

9. Murray Marks. From George Charles Williamson’s Murray Marks and his Friends: A Tribute of Regard (1919).

10. Murray Marks’ trade card. From George Charles Williamson’s Murray Marks and his Friends: A Tribute of Regard (1919).

11. Portrait of Joseph Mayer by William Daniels. Courtesy National Museum Liverpool.

12. The ‘Mummy Room’ in Mayer’s Egyptian Museum. Courtesy of Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries.

13. Stephen Wootton Bushell. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, PH118-80.

14. The Bronze Pavilion at the Imperial Summer Palace. Reproduced by permission of Durham University Museums.

15. Satirical engravings by George du Maurier. Punch Almanack (December 1875). Courtesy of the author.

16. Aston Webb’s South Kensington complex. Getty Images.

17. The glass palace of the Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester. Art-Treasures Examiner: A Pictorial, Critical and Historical Record of the Art-Treasures Exhibition (1857). Reproduced by courtesy of the University Librarian and Director, The John Rylands University Library, The University of Manchester.

MAGPIES, SQUIRRELS & THIEVES

Preface

Today we are accustomed to the mechanisms that allow collectors to build a collection: auctions and antique dealers, car-boot sales and internet trading sites. We expect to have public collections in town and city museums, even if we rarely visit them. The motivations that drive collectors have frequently been examined by psychologists and psychoanalysts, and this has given us some understanding of why collecting is such a popular activity and how it can become so obsessive. What I want to do with this book is to take a step back, to a period during the nineteenth century when many of the aspects of collecting which we now take for granted were being newly explored, when collectors were emerging into the public eye and when the hunt for objects was at its most inventive and eccentric. The thrills and perils of Victorian collecting will, in some respects, appear very familiar; it was the collectors of the nineteenth century who laid the foundations for later collectors and many of their networks remain. In other ways, however, we will discover outlooks and experiences very different from those which collectors might expect today. Victorian collecting had a character of its own, and it is this robust and intrepid spirit of adventure that I hope to convey.

There was no single archetypal Victorian collector: individual tastes meant that one collection was very different from another. Some collections were ordered, scholarly or scientific; others were quirky, highly personal narratives. Changes in fashions, attitudes and economic climate also influenced the objects people chose to collect. This book presents the stories of five collectors to give some sense of this diversity and of the ways in which collecting evolved through the nineteenth century. It also uses these individual stories to explore more general issues about collecting. What is a ‘collection’? What kind of cultural, social and political factors influence the life of a collection? What drives the collector? What is the relationship between the private collector and the public museum?

Each of my five collectors left lively archives, letters or journals which document their collecting and each has a fascinating story to tell. Between them, they turned their attention to all kinds of art and historical objects. John Charles Robinson was an influential curator at the South Kensington Museum, which would be renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899, becoming one of the most famous public collections in the world. He collected both for the museum and for himself, indulging a taste for significant, and often expensive, pieces of art and becoming a specialist in the Italian Renaissance. Lady Charlotte Schreiber, the widow of a steel magnate and an intrepid traveller, sought out china and playing cards, fans and glass in showrooms and junkshops across Europe. Murray Marks, a dealer as well as a collector, used his connections in Holland to exploit the fashion for blue-and-white ceramics and his friendship with the Pre-Raphaelites to create elaborate domestic interiors. Liverpool jeweller Joseph Mayer had a taste for Roman remains, Egyptian antiquities, coins, Anglo-Saxon archaeology and quirky objects from history. Stephen Wootton Bushell was sent to China as doctor to the British delegation and ended up becoming a pioneering expert on Chinese art.

The five individual stories offer a portrait of the collector, from the eccentric and obsessive to the scholarly and the professional. Together, they also show us how art-collecting changed during the Victorian period, moving away from the great pictures and sculpture that had fascinated the wealthy in the eighteenth century towards smaller, more varied decorative objects. Science and natural history collections, which were equally popular and active at this time, could not be covered within the scope of the book, but it is worth bearing in mind that this created yet another growing community of collectors, working alongside – and occasionally overlapping – with art collectors. For those whose tastes lay towards stuffed animals, geological specimens or mechanical instruments, there was a correspondingly influential and flourishing network of organizations, museums and collectors to feed their enthusiasm.

None of my five collectors is well known. Even John Charles Robinson has been little studied; in comparison to his colleague at the South Kensington Museum, Henry Cole, his work has been overlooked. Only some of the objects from their collections were important and valuable; some were just as much a demonstration of individual taste or little more than a frivolous purchase. None of the collections survives intact to be seen now. But each one was significant in its own time; some were even famed. And, taken together, these five histories give an insight into a Victorian phenomenon that went much further than just a handful of extraordinary lives, revealing a passion for collecting that helped shape how we see the nineteenth century and the legacy it has bequeathed to us today.

Catching the Collecting Bug

CHAPTER ONE

Exhibition Road, London, 1862

It was a hot June day in 1862. South Kensington was bustle and dust and noise, as it had been for months. Horses, carriages and omnibuses moved slowly in the packed streets. On Exhibition Road, on a site that would, in twenty years’ time, become home to the terracotta columns of the Natural History Museum, two great glass domes shone in the sun. They formed the extravagant centrepiece of the London International Exhibition of Industry and Art, an enormous fair of artworks and manufactures from across the world in the tradition of the 1851 Great Exhibition. Visitors queued at the entrances, eager to see what was on show, crowds inside pushed their way through the glittering displays and Victorian London was, once again, in thrall to the excitement of spectacle

Sponsored by the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, the new exhibition boasted 28,000 exhibitors from thirty-six countries. The specially erected building, designed by government engineer and architect Captain Francis Fowke, covered 23 acres of land, with two huge wings set aside for large-scale agricultural equipment and machinery, including a cotton mill and maritime engines, and a façade almost 1,200 feet long, of high arched windows, corner pavilions, columns and flags. At a cost of almost half a million pounds, the exhibition was intended to dazzle and impress even those who had visited the Crystal Palace extravaganza a decade earlier, and the two crystal domes of Fowke’s design, each 260 feet high and 160 feet in diameter, were then the largest domes in the world, wider than (although not quite as high as) both St Paul’s in London and St Peter’s in Rome.

Not everyone liked the building. The popular press seemed to think the vast domes resembled nothing so much as colossal overturned soup bowls; Building News joined other national papers in describing it as ‘one of the ugliest public buildings that was ever raised’.1 But the exhibition inside was very much an attraction. In the six months of its life, between 1 May and 1 November 1862, over 6 million visitors paid between a shilling and a pound, depending on the day, to see new inventions, industrial machinery, home wares, works of art and the occasional splendid folly, such as the huge pillar of gold sent from the Australian gold rush. Not to be put off by a touch of architectural vulgarity, the London crowds flocked to the display galleries where bootmakers rubbed shoulders with baronets; young designers sketched ideas; whiskered manufacturers confided trade secrets; pickpockets, no doubt, flourished, and everyone had a good time.

The taste for this kind of event was by now well established; most visitors already knew how to negotiate the vast spaces and overwhelming displays. They liked the bewildering array of exhibits, the crowded corridors and the chance to see and be seen. Not only the 1851 Great Exhibition, but other international exhibitions such as the 1855 Paris Exhibition and, closer to home, the 1857 Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester, had accustomed the Victorians to the idea of huge and eclectic displays, sparkling showcases for the most beautiful, the most efficient and the most innovative. Even those who had never before visited such an exhibition would have read about them in the newspapers, and seen all kinds of prints and photographs of what they had been missing. This new event filled the front pages of the press: the Illustrated London News was just one of the papers to issue a special event supplement, and to use its editorials to update readers with news of the exhibition’s progress. Visitors came to the International Exhibition at South Kensington expecting to be amazed and entertained by the practical, the pioneering and the extraordinary.

The objects brought together under Fowke’s clumsy crystal domes included everything from a working forge to sewing machines, from slates and rock salt to the Brazilian ‘Star of the South’ diamond. The exhibition was a symbol of mid-Victorian aspiration, manufacturing success and consumer confidence. It was a message to the world about the ambition of Britain and its Empire. But to the millions of visitors that pushed through the crowded galleries, it was also, quite simply, a chance to admire and desire beautiful and unusual things. It evoked, on an enormous scale, the Victorian idea of the collection and what it might mean to bring things together, to compare them, to own and value them, to present them in public with pride.

It was not only the brightly painted and lavishly ornamented arcades of the International Exhibition that hummed with activity. On the other side of Exhibition Road, more objects and more collections were attracting public interest. The new South Kensington Museum, which had been emerging since 1857 in a mish-mash of temporary buildings, was also noisy and crowded. The recently opened permanent galleries of the North and South Courts – also designed by Francis Fowke – more than rivalled the glamour and glitter across the road. Here, too, there was a glass roof to let in light and air. Boldly painted walls in deep blood-red and purple grey prepared the eye for corridors packed with elaborate highly coloured arrays of patterned wallpapers, mosaics, friezes and stained glass. Here, too, visitors clustered close together around cases of fascinating and attractive things, preening, laughing and flirting, enjoying the buzz. Voices, and the chink of fine china, drifted from the mock-Tudor refreshment rooms where colourful flocks of women took afternoon tea; in the new display spaces collectors, connoisseurs and the simply curious marvelled at some of the world’s finest art objects brought together for the delight of the public.

This was the ‘Special Exhibition of Works of Art of the Medieval, Renaissance, and more Recent Periods, on loan at the South Kensington Museum’, a complementary – or perhaps rival – attraction to the more manufacturing-based displays across the road. The catalogue played down the ambition of the exhibition, describing it simply as ‘fine works of bygone periods’, which had been made possible with ‘the assistance of noblemen and gentlemen, eminent for their knowledge of art’.2 In fact, the displays featured some of the rarest and most beautiful objects ever set before the British general public, over 9,000 works of art from over 500 of the country’s richest and most influential owners, from the Queen, aristocracy and the Church, to London livery companies, municipal corporations and public schools. These were private treasures, not normally on open display, brought together for the first and only time – a triumph of negotiation and diplomacy.

The exhibition covered over 500 years of art production, and included all kinds of media, from painting, ceramic and glass, to metal, ivory and textiles. Objects were organized in the catalogue into forty categories, which more or less corresponded to the layout of the galleries. There was no chronological arrangement to the displays, which were bewildering in their haphazard glamour and sheer abundance. Beginning with sculptures in marble and terracotta, the exhibition moved on to nearly 300 carvings in ivory, bronzes, furniture, Anglo-Saxon metalwork, enamels, jewellery and glass, textiles and illuminated manuscripts. There was a Sèvres porcelain vase in the form of a ship painted with cupids and flowers; a Limoges enamel casket, one of the many enamels on display from the collection of the Duke of Hamilton; a silver-gilt handbell which ‘doubtless’ came from the chamber of Mary Queen of Scots; and a modest pair of Plymouth porcelain salt cellars, in the form of shells, belonging to the Right Honourable William Gladstone MP.

Contributors had loaned not only individual objects but sometimes entire collections, often with ancient family roots. This was particularly true in the case of bookbindings, portrait miniatures, jewellery and cameos, the popular mainstays of country-house collections: ‘The Devonshire Gems’, for example, assembled in the eighteenth century by William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire, was displayed in its entirety, apart from eighty-eight of the cameos which had already been committed to the International Exhibition. So extensive and unique was the collection, and so difficult to assess in the short period of time that had been given over to organizing the exhibition, that the catalogue was forced to confine itself to listing just a few ‘of the finest gems’.

The show was designed to delight and amaze, without reference to the grind of manufacture and industrial production that was the backbone of the displays at the International Exhibition. Its emphasis was on the romantic and the historic, and it focused public attention on the beauty of medieval and Renaissance objects for the first time, introducing unknown styles and techniques. The press marvelled at a display that was ‘unequalled in the world’ and ‘rich beyond all compute and precedent’, and the chance to see rare works of art drew visitors from across the country.3 But this was not just a splendid art exhibition: with objects from over 500 collectors, each of whom was named on labels and in the catalogue, the resplendent galleries were specifically designed to bear witness to the richness and variety of British collecting. The packed cases clearly showed how deeply embedded was the idea of the collection, both in national institutions like the monarchy and in the private lives of many of the country’s wealthiest and most influential men and women. And over a million visitors – more than a third of the population of London – came to the new museum to see the displays, suggesting how great was the public appetite for the beautiful and quirky, and how widespread the curiosity about, and commitment to, collecting.

Making all this possible was one man – John Charles Robinson. Robinson was a collector himself, a connoisseur, but he was also Librarian-Curator at the South Kensington Museum where he had responsibility for buying objects, researching the collections and, as the exhibition triumphantly demonstrated, creating public displays. Crucial to all of this activity, for Robinson, was nurturing a community of collectors, creating an intimate mutual relationship between individuals and the museum that would benefit everyone. And at the heart of this community, he put himself. He knew all the most active and influential collectors, dealers and scholars; he made some of the most glamorous and talked-about transactions. It was Robinson’s influential network of contacts that turned the Special Exhibition from a modest display of private loans to the stunning art show that greeted the South Kensington visitors.

Robinson was a founder member of the Fine Arts Club, a London-based club of wealthy collectors. In 1858, he wrote to his superiors at South Kensington to suggest that he and his collecting colleagues should organize a small and select display of historical art, as an adjunct to the forthcoming International Exhibition. It would provide something extra, he suggested, for those whose tastes inclined towards older and more refined pieces than would be included in the trade-based displays at the International Exhibition; it would recognize that the public’s interest in all kinds of art had been stimulated by events like the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in the previous year, when over a million visitors, from royalty to cotton-mill workers, had clamoured to see everything from sculpture and armour to photographic montages and Limoges enamels. Permission for the loan show was given, but there were plenty of sceptics who were quick to dismiss the proposal, and members of the press warned that Robinson’s enterprise would be ‘overshadowed by its imposing and all-absorbing neighbour, and. . . be recognized only by the connoisseur’.4

Robinson, however, had other ideas. Through the Fine Arts Club, he formed a committee of seventy of the nation’s most influential collectors, including the aristocracy and clergy, eight Members of Parliament and Sir Charles Eastlake, President of the Royal Academy and Director of the National Gallery. Between them, these men knew almost every collector in the land. Robinson’s exhibition became a rallying point, a prestigious and glamorous event that celebrated collecting. ‘Private cabinets were thrown open with an alacrity which showed that the only offence to be feared was not rifling them enough. . .’ marvelled the Quarterly Review. ‘The great floodgate was opened.’5 Over the coming months, more and more treasures were pledged to the exhibition until the organizers were swamped by both the sheer volume of objects they were being offered and the practical demands of getting everything safely to the London galleries.

When the exhibition finally opened its doors, it was something of a triumph, a tribute to Robinson’s unrivalled network and what the international press called his ‘incessant activity’.6 Probably no one else could have made it happen. It clearly showed the value of bringing works of art together for comparison, and it began to inspire a new taste for the medieval and the Renaissance, then obscure periods that had received little critical attention. Robinson’s scholarly catalogue, too, was recognized by specialists as ‘a work of the highest importance’.7 But perhaps more than anything else, the exhibition signalled to the world the extent of Victorian collecting. For the first time, it offered a glimpse of just how many collectors there might be. It gave a sense of the shared and irrepressible enthusiasm that brought together so many of the country’s men and women, and it revealed the range and magnificence of the objects they collected. It brought into the open a fascination with things that was shaping people’s homes, forging municipal and national identities, and putting the collector at the heart of an increasingly commodified world.

CHAPTER TWO

The Useful and the Beautiful

In all kinds of ways, the buzz of activity at South Kensington during 1862 was a legacy of the enormously successful 1851 Great Exhibition, a monumental enterprise that had as much influence on political, economic and social life as it did on art, science and technology. Like the 1862 International Exhibition, the earlier event was organized by the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, which had been established in 1754 to support activities as diverse as spinning, carpet manufacture, tree-planting and painting. It soon became known informally as the Society of Arts (finally to become the Royal Society of Arts in 1908) and by the 1760s it was holding regular exhibitions, both of contemporary art and industrial innovations. But these were relatively modest affairs and there was little British precedent for such a huge and ambitious undertaking as the Great Exhibition. What is now commonly recognized as a landmark of Victorian achievement was a courageous experiment, and almost didn’t take place at all.

The exhibition was intended to restore the fortunes of British trade and manufacturing, by showing off British endeavour, bringing together the best of the world’s products as an inspiration to business and providing models for the future. A ‘Select Committee on Arts and their connection with Manufactures’ reported to the government as early as 1835 that both manufacturers and the public needed educating in matters of art and design. Pandering to a public appetite for novelty, and with an eye on keeping production costs to a minimum, British design standards were falling. Skills were dwindling and foreign competitors were flourishing. In the shops and department stores increasingly powerful middle-class consumers were flexing their spending muscles in unexpected directions, choosing goods from rival countries – tableware and furniture from France, Italian ornaments, and even glassware or jewellery imported from America. They were displaying what the government regarded as dubious taste; turning up their noses at traditional British wares and instead filling their drawing rooms with showy conversation-pieces that more obviously displayed their wealth and status. In the face of such competition, British manufacturers were suffering and the economy was faltering. What was needed was a showcase where examples of the best design could be displayed; where diligent manufacturers and aspiring young designers could come and study; where they could learn new skills and be inspired by new patterns.

In the course of the planning process leading up to 1851, however, and in response to the need to raise money and support for the project, the organizers attempted to head off public criticism by accommodating, wherever they could, all kinds of aspirations for the event. The apparently simple original plan – to raise the standards of British industrial design – was reshaped to take account of a range of other preoccupations and priorities. Local committees were established to help source objects and raise awareness and funds, but these often had their own agendas, from Chartism to women’s rights. While on a national level it became clear that, to survive, the exhibition would need to reflect, among other things, the enthusiasm of the Prime Minister, Lord John Russell, for celebrating commercial liberalism and free trade; the desire of the influential East India Company to show off the Empire’s raw materials; the Church’s concern with illustrating divine benevolence; and the conviction of the liberal middle classes that the show should assert the British political and social model to the rest of the world. Not surprisingly, these pressures took their toll. The original intentions faded in the face of so many demands and the clear purpose of the exhibition faltered. The final display, while spectacular, was confused and often discordant, and the ‘meaning’ of the exhibition was further addled by the enormous variety of interpretations offered by the press and visiting public. No one could quite agree, it seemed, exactly what they were looking at.

Yet, despite these problems, the idea of the exhibition caught the popular imagination, both at home and abroad. Enough of the original focus on manufacture and trade remained to inspire generations of industrial spectacles across the world over the course of the century, while in the immediate aftermath it spurred the French into organizing a World Exhibition of their own, with an understandable emphasis on restoring French manufacturing and design to pre-eminence. The French, in fact, had already hosted an Industrial Exhibition in 1844 and had a tradition of official exhibitions of art and industry stretching back to the late eighteenth century. The London show, however, had been on a different scale, forcing organizers across the English Channel to redouble their efforts in response. The subsequent 1855 Paris Exhibition was even larger and more elaborate than the Great Exhibition had been, although it was significantly less successful financially (leaving a crippling shortfall of over 8 million francs) and visitor numbers were comparatively low. It succeeded in inflaming old Gallo-British rivalries even further, however, and driving home the idea that British design was still lagging behind its European counterpart. In London, there seemed nothing for it but to stage yet another event, bigger and better than any that had preceded it, demonstrating beyond doubt the technological progress that the British were making across the world. So work began on the 1862 International Exhibition and, despite financial setbacks, conflict in Italy and America which threatened to derail foreign loans, and the untimely death of Prince Albert in December 1861, just months before the scheduled opening, the show managed, in scale at least, to eclipse all others.

But the International Exhibition was not the only legacy of 1851 at South Kensington. Surplus funds from the Great Exhibition (around £180,000) were set aside to improve standards of science and art education, and parcels of land were bought around the district for a number of educational and cultural projects. One of these was the new museum, which had been in a temporary home at Marlborough House on Pall Mall, and which also inherited large numbers of objects from the Great Exhibition. Just as significantly, the museum’s first Director, Henry Cole, had been a key organizer of both the 1851 and 1862 extravaganzas, and brought with him a commitment to the original Great Exhibition principles of improving standards in manufacturing, raising the quality of industrial design and educating public taste through the display of objects. Perhaps the greatest legacy of the 1851 exhibition, however, was the least tangible one: a growing sense that collecting and display was a serious, public affair. Coverage in the press, political debate and drawing-room gossip began to discuss, appraise and compare works of art, and in the wake of this enormous attention there was an increasing appreciation that objects could have profound personal and social meanings.

The Great Exhibition offered the most visible, spectacular evidence of a fascination with collecting that had been growing since the beginning of the century. It showed just how many issues might be inherent in the apparently simple idea of making a collection. And, as a result of this, there was increasingly open and varied debate about what kind of role art might have in public life, about the purpose of design, and about thorny questions of taste, patronage, ownership and education. This was a period when even many of the defining terms we take for granted today were new and the distinctions between them ambiguous: what, exactly, was a ‘public’ collection? What was a work of ‘decorative’ or ‘applied’ art? How could you define the difference between an amateur, a connoisseur and a professional? What was a curator’s role?

Many of these questions would take decades to resolve; some are still being debated today. But what was immediately clear was that there was more interest than ever in what collecting might mean, and how collections might best be achieved. By the middle of the century, debates that had been rumbling for years, and which were implicit in the collecting activities of Robinson’s influential colleagues and the wealthy members of the Fine Arts Club, were being aired ever more frequently in public. It was increasingly evident that collecting could not be seen as a private interest detached from events going on around it; it was part of a wider conversation inextricably linked to political ideology and social change. Robinson’s 1862 loan exhibition came, in many ways, at the perfect time. It made collecting visible, topical and desirable at the moment when the discussions inspired by the Great Exhibition were reaching maturity.

Appointing Henry Cole as Director of the South Kensington Museum signalled the government’s desire to continue with the work they had begun at the Great Exhibition. Intimately involved with both the 1851 event and the 1862 International Exhibition, and publicly espousing the values behind them, Cole was an enthusiastic advocate for the campaign to improve standards and educate public taste. He would use the objects on display at the museum to show people what they could and could not like; what they did and did not want to buy. He would change habits and restore manufacturing fortunes. He would, he boasted, ‘make the public hunger after the objects. . . then they [will] go to the shops and say, “We do not like this or that; we have seen something prettier at the Museum”; and the shop-keeper, who knows his own interest, repeats that to the manufacturer and the manufacturer, instigated by that demand, produces the article.’1

Even by Victorian standards, Cole was fiercely energetic, an apparently unstoppable force of opinions and activity. By the end of his life, in 1882, he was an institution, known as ‘Old King Cole’, but both his stubborn, temperamental approach and his reforming zeal tended to arouse admiration and antipathy in equal measure: ‘His action has often been harshly criticized,’ began his obituary in The Times. ‘His untiring energy and perseverance have frequently made him enemies.’2 He was a career civil servant; having joined the Public Record Office in 1823 at the age of fifteen, he was the author of a series of pamphlets advocating reform of the public record system. He wrote for a range of newspapers and journals and in 1840 won a prize for developing a workable Penny Postage plan. By the time he turned his attention to art and manufacturing, around 1845, he was already an experienced and confident administrator. He immediately began to assist the Society of Arts on a series of exhibitions to stimulate industry and invention, finally securing his place, according to his obituary, as ‘the leading spirit and prime mover’ of the reform impulses which led to the Great Exhibition.3

Following this success, Cole was invited in 1852 to reorganize the government Schools of Design. These had been established in twenty cities from 1837, one of the earliest indications of the government’s commitment to design reform. Created by the Board of Trade, they were supposed to promote an establishment consensus on art and good taste, improving education and training new designers in approved styles and techniques. In practice, however, many of the Schools had concentrated as much on academic art as on industrial design and during the 1840s a series of internal battles raged over exactly what should be taught. Cole aimed to give the system a new sense of direction and control, and put the focus firmly back on to ‘useful’ skills. As the first step, he put the Schools under the control of a new Department of Practical Art, soon renamed the Department of Science and Art, a subdivision of the Board of Trade. He appointed himself Superintendent, and made clear his intention to direct things with a firm hand: the new department was to be managed from South Kensington, with his protégés slotted into key roles.

The new museum was part of the same package. It was seen as another weapon in the battle for design reform, working alongside the Schools but with a more public emphasis. It fell under the same umbrella at the Department of Science and Art, which meant there was no independent board of Trustees to distract or hinder Cole. It could build on the impetus that had been created by the two industrial exhibitions, giving a more permanent face to government policy and taking its place without restrictions as the flagship of a wider movement for improving practical education nationwide. The galleries were intended to be just as instructional as any school, driving home messages about art and its role in national life. Cole glowed with the righteousness of educational principles: in a rallying speech, he laid out his aim to ‘woo the ignorant’ and ensure objects at the museum were ‘talked about and lectured upon’ until no one could be left in any doubt about what constituted good taste.4 No longer would the manufacturing and shopping public make bad choices: they had someone to guide them. The South Kensington Museum would be useful, practical and modern, displaying things that could be copied, redesigned and mass-produced, providing clear information about process and construction, and lucid explanations of design principles. It could show reproductions, if that’s what it took to make a point. It would show art with a purpose; art which could, with Victorian skill and confidence, be made to shape the future.

As the museum’s leading curator, Robinson worked closely with Cole in acquiring objects and arranging them for display. He supported the general principles of education at the museum but he did not fully share Cole’s views about the importance of manufacture and the best ways to instruct and influence the public. His real interest was in beautiful and historical things, and he was convinced that he knew better than Henry Cole how to find, treasure and display them. His relationship with his employer was edgy and barbed, liable to erupt in furious explosions. Both men were obstinate, confident and opinionated, and their ambitions collided too frequently for comfortable coexistence. Robinson was not above claiming, in public, that Cole did not know very much about art; Cole struggled to assert his authority over his excitable curator. Inevitably, in time, the friction between them would rub bare uncontainable feelings of anger, disappointment and betrayal. Within a few years, working relations would sour beyond the point of no return. But for now Robinson bided his time. It was with the two contrasting displays either side of Exhibition Road that he made his case.

In many ways, the two men and their exhibitions represented opposing sides in the debate about the value of art that had been raging for over a century, but into which the Victorians had entered with particular gusto. Did art need to have a function or purpose, or could it exist for its own sake? How did one attach value to an object – because it was useful or because it was beautiful? Did art have to be linked to social and moral responsibility, or was it autonomous, following its own rules? Such questions had been exercising educated minds since Edmund Burke’s influential Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, published in 1757, and the emergence of the Romantic movement’s preoccupation with personal creativity and emotional and artistic truth at the end of the eighteenth century. Proposals to create a national gallery of art at the beginning of the nineteenth century had reinvigorated the debate, in and out of Parliament, setting the case for historic art against modern examples, and looking at ways of organizing displays to best make them meaningful. An exhibition of ‘Ancient and Medieval Art’ held by the Society of Arts in London in 1850 and the Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester seven years later both linked the viewing of works of art to a useful purpose: ‘To the Artist and Manufacturer, an opportunity is afforded of comparing the handiwork of ancient times with the productions of our own skill and ingenuity,’ explained the 1850 catalogue, ‘to the Amateur, means are supplied of correcting the taste and refining the judgement’.5

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the discussion was by no means confined to the intellectual elite. Most of those in the public eye, as well as those writing in the popular press, had an opinion. Nor was this a distinctly British trend: across Europe, museums, galleries and governments were discussing what kind of art to collect, and how to show it. Many successful mid-century Victorians considered the fine arts to be some kind of adjunct to the real business of mechanical invention and production, where value was attached to accuracy and originality. Others maintained that art could not be conflated with commerce and that its value was as much emotional as practical. Writers like Tennyson, the poet laureate, and painters like William Holman Hunt preferred their art with a moral message; advocates of the Arts and Crafts movement emphasized the utility and social community of craftsmanship; on the other side, critics like Walter Pater argued vehemently that formal, aesthetic qualities should take precedence over moral or narrative content. In 1857, the critic and writer John Ruskin launched a scathing attack on the South Kensington Museum because, in his opinion, ‘fragments of really true and precious art are buried and polluted amidst a mass of loathsome modern mechanisms, fineries and fatuity’; ten years later, Matthew Arnold’s influential series of articles, ‘Culture and Anarchy’, appeared in the Cornhill Magazine, exploring ‘what culture really is, what good it can do, what is our own special need of it’ and discussing the role of art in a rapidly changing world.6 It was not a debate that was going to be resolved in the galleries of the South Kensington Museum: at the end of the nineteenth century, it was still a matter of intense argument as the Aesthetic movement and Oscar Wilde made an ostentatious case for ‘Art for Art’s Sake’. But many of the museum visitors would have been well versed in the discussion, and would have recognized in Robinson’s loan exhibition an unexpected contrast to Henry Cole’s usual principles of display. Robinson’s emphasis on beauty and on collecting for pleasure set the display well apart from the paean to commercial progress that was Henry Cole’s International Exhibition.

Robinson was clear on the point: for all Cole’s hectoring, what visitors really wanted to see – what a museum was about – was the exhibition of the most exquisite and refined objects. ‘What’, he asked an audience at one of his lectures, ‘is there to trust to but the silent refining influence of the monuments of Art themselves?’7 Not lectures and labels, not modern mass-produced pieces straight from the production line, but the ‘monuments’ most able to assert their ‘silent refining influence’ – the medieval silverware, the exotic oriental screens, the jewelled Renaissance chalices. Robinson was a connoisseur: his enthusiasm for collecting went hand-in-hand with an appreciation of the beautiful. And, as the Victorians continued to debate the ways in which art might influence their lives, more and more people were making their allegiances evident by also choosing to collect, making space for objects in their homes because they liked them there and because the desire for lovely things seemed irrepressible.

CHAPTER THREE

A Public Duty and a Private Preoccupation

The mid-Victorian period saw a boom in collecting. Explorers and adventurers to new and distant lands brought back plants, seeds and shells, pinned butterflies, bright beetles and stuffed animals to fill the gardens and display cases of the natural history collector. Enthusiasts dug for fossils, dinosaur bones and geological specimens, while archaeologists unearthed beads, weapons and brooches to fill shelves and cabinets. Art collecting moved away from the country homes of the rich into the fashionable townhouses of the increasingly confident and wealthy middle classes, and in turn attention moved from Old Master paintings and sculptures to more domestic works in materials such as ceramic or glass. A trend for highly decorated parlours, stuffed with all kinds of pictures, statues and objects, became endemic: showing off a collection of curios sent out messages about social status, and helped the owner appear educated and cultured.

Collecting had long been part of the upper-class way of British life. Most of the country’s leading families boasted a collection of art and sculpture, jewellery or elite porcelain such as Meissen or Sèvres. The tradition of the Grand Tour had been flourishing since the middle of the seventeenth century, serving not only as a cultural education and a rite of passage but also as an opportunity to add to the family’s collection by buying up works of art to ship home. Collecting was considered a fit occupation for a gentleman, drawing on the habits of European royalty and the erudite tradition of the Wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities, which had emerged among the wealthy during the Renaissance. The custom for collecting was inextricably linked to power, prestige and riches: during the sixteenth century, the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II, for example, was an obsessive collector of paintings, and the seventeenth-century Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria employed the Flemish painter David Teniers the Younger to care for a hugely expensive collection which boasted everything from works by Italian masters to Cromwellian souvenirs of the English Civil War. The fortunes of the royal and aristocratic houses of Europe were clearly reflected in the ebb and flow of their collections, which were regularly sold, moved or broken up as the result of marriage and war, gambling debts and revolution. The Orléans Collection of over 500 paintings was assembled at the beginning of the eighteenth century by the French prince Philippe II, Duke of Orléans and nephew of Louis XIV. Its core, however, already dated back to the 1600s when Swedish troops sacked Munich and Prague during the Thirty Years War, looting masses of objects including the Habsburg collections of Rudolph II and Emperor Charles V from Prague Castle. These were added to by Queen Christina of Sweden, with a particular focus on Renaissance and Roman art, before being sold off at her death in 1689 to cover her debts. When he bought the collection, Philippe II added to it extensively, investing in a range of prestigious works from all over Europe including many of the key pieces accumulated by Charles I of England, another avid collector. The collection was celebrated as one of the gems of European culture, housed in the magnificent Palais Royal in Paris, and asserting the power and splendour of the French monarchy.

When Philippe died in 1723, his pious son Louis inherited the collection. But his tastes were not the same as his father’s, and he was alarmed by the subject matter of some of the paintings. In a fit of religious zeal, he attacked several of the most famous works with a knife, slashing Correggio’s Leda and the Swan which depicted an erotic scene from Greek mythology, and ordering three more of Correggio’s works to be cut up in the presence of his personal chaplain. The collection survived, but neither Louis nor his son, Louis Philippe, had the will or money to be active in their collecting, and at the end of the eighteenth century the pieces were put up for sale in a desperate attempt to pay off enormous debts. It was the complex political pressures and the financial uncertainty of the French Revolution which finally decided the fate of the collection, however. Extravagant displays of personal wealth and royal power were out of fashion, a liability, and in 1793, just as Louis Philippe was arrested at the height of the Reign of Terror, almost 200 paintings were shipped over to London’s salerooms. In the months prior to his execution at the guillotine in November, negotiations were finalized for selling the rest of the collection, mainly Italian and French paintings, to a Brussels banker.

During the mid-seventeenth century and in the period following the French Revolution, political upheaval and changes in European social order saw many collections from the Continent, such as the Orléans collection, dispersed, relocated or re-formed. By contrast, in England the nineteenth century started with considerable security among the landed classes, with the aristocracy generally thriving and their collections benefiting from the distress of their European counterparts. But this gradually changed. In August 1848, The Times reported on the sale of the collection at Stowe, the home of the 2nd Duke of Buckingham and the first of numerous country-house sales that would have been unimaginable a couple of decades earlier. It was, the report explained, ‘a spectacle of painfully interesting and gravely historical import . . . an ancient family ruined, their palace marked for destruction, and its contents scattered to the four winds of heaven’.1 The auction was the first symptom of a lingering malaise among country estates that was to last throughout the century, and to bring more and more art treasures on to the open market. A changing economic climate favoured industry rather than land as a way of making money, and old families feeling the pinch often turned to the sale of at least part of their collections as a way of boosting funds.

In 1882, the Settled Land Act brought things to a head. The old system of entailment had prevented the sale of land and collections, keeping them intact. Property passed from generation to generation through the eldest son (or, in the event of there being no son, via another male relative). Under the rights of primogeniture, he held a lifetime’s interest in the land, house and contents: he was not free to sell or divide anything. With the new Act, this age-old arrangement was overturned. Restrictions on the sale of property were lifted and the tenant for life was given much stronger powers for dealing with his inheritance. Suddenly, family collections could be viewed as marketable commodities, and so converted into cash – and treasures from the most venerable and celebrated collections soon came under the hammer. In 1882, immediately after the Act was passed, the Duke of Hamilton sold most of the contents of his South Lanarkshire palace for almost £400,000 (the equivalent today of over £30 million); two years later, at Blenheim Palace, the Duke of Marlborough was given leave to dispose of some of his family’s collections in a series of sales. The 18,000 volumes of ‘The Sunderland Library’ raised £60,000, and over the following years a collection of enamels and some of the palace’s major works of art, including Raphael’s Madonna degli Ansidei, were also sold.

The collectors who took advantage of these misfortunes were often members of the newly influential middle classes. After a series of complicated financial manoeuvres, much of the Orléans collection finally found a home in Britain when it was bought in 1798 by a consortium consisting of Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, a coal and canal magnate; his nephew Earl Gower; and the Duke of Carlisle. But, in a reflection of changing fortunes and tastes, it was to be broken up yet further. Only 94 of the 305 paintings were retained for the family galleries. The rest were sold on again, raising over £42,000 to cover expenses, finding their way into the hands of a range of buyers that included four painters, four MPs, six dealers, two bankers and six gentleman amateurs.2 While the sale of the collection into the hands of the Duke of Bridgewater seemed at first to reinforce the impression of ownership by the aristocracy, it was the Duke’s new wealth from manufacturing and trade, rather than ancient land rights, that made the deal possible. And the sales which followed showed even more clearly how the finest objects were moving out of the hands of the European elite into the homes of the middle classes – bankers and MPs, as well as those dealers who were making a profitable profession out of what had once been a royal diversion. Collections that had been as much a display of power and influence as cultural appreciation were being broken up and abridged. The very nature of collecting itself was beginning to be transformed.

On the death of the Duke of Bridgewater in 1803, his collection was put on semi-public exhibition in Westminster, open on Wednesday afternoons to those who wrote requesting a ticket, or to artists recommended by the Royal Academy. This was a further demonstration that the idea of the inaccessible, aristocratic treasure house was beginning to disappear. Increasingly, private collections were getting a public airing, some being bequeathed to national or regional galleries but many more occupying a grey area by allowing restricted access to a vetted group of visitors. It was a long way from full public access: the Bridgewater collection was exhibited grandly in Cleveland House with a staff of twelve luxuriously liveried attendants, giving an impression not unlike a private palace. But it offered the aspiring middle classes, in particular, new opportunities for viewing and it was an indication of changing perceptions of the role of collecting and collectors. Collecting was no longer the preserve of the very rich; objects that had once been in the collections of royalty were now finding their way into much more modest houses and on to sightseeing itineraries. The changing face of European society was being reflected in increasingly widespread opportunities to collect.

Paintings and sculpture, however, still demanded plenty of wall and floor space, and investing in Old Masters required a particular kind of education. In addition, around the middle of the century, there was a dramatic rise in the prices of the kinds of works collectors had traditionally sought. New directions had to be explored. More and more, the emerging middle-class collectors took an interest in different kinds of pieces, particularly those they could pick up at reasonably limited expense, such as old English glass or pewter, decorations for the home – including mirrors, vases and textiles – and objects which might prove to be a shrewd speculation, like Staffordshire ware or silver. Although one or two earlier collectors had been interested in these areas – most notably, perhaps, the eighteenth-century historian and politician Horace Walpole – they had, until now, been largely neglected. By the middle of the century, however, this was changing and several large-scale, highly public sales helped cement the idea that collecting had moved away from its traditional preoccupation with expensive masterpieces and was becoming accessible, educational and profitable. In particular, in 1855, Christie’s in London undertook the sale of the collection of Ralph Bernal, who had died a year earlier. Bernal epitomized the new type of collecting. He was educated and cultured, but as a barrister and MP he was firmly middle class. His apparently mystical ability to hunt out treasure from ordinary bric-a-brac shops earned him the epithet ‘lynx-eyed’ in The Connoisseur, an illustrated magazine. And the £20,000 he had invested in his collection was turned into nearly £71,000 at the Christie’s sale which lasted thirty-two days and was an extravaganza of the metalwork, ceramics, glass and miniatures that were beginning to fascinate collectors.3

The impulses that were evident in Britain were repeated across Europe as the political and social fabric was rethreaded. Shops and dealers sprang up in major urban centres to cater for the increasing number of collectors seeking out treasure. They were not just the aristocratic sons of the ruling European classes, professional artists or dilettantes; they were merchants and bankers, clergy, military officers, wives and mothers. There was a revolution in attitudes, suggesting everything was within reach, for more or less everybody. What made English collectors unique, however, was their taste for showing things off in their homes: ‘They like to live surrounded by their pictures and antiquities,’ marvelled Gustav Waagen, art historian and director of the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum (later the Bode Museum) in Berlin, something that was ‘virtually unknown elsewhere in Europe’.4

This intimate relationship between a collector and his things intrigued the public. As more and more homes began to display the spoils of private collecting, so the press began to carry detailed coverage of major sales and to record the growing numbers of people seduced by the idea of the collection. After the Bernal auction, Punch noted that the country had been gripped by ‘Collection Mania’, an ‘enormous quantity of money’ changing hands and stimulating ‘the ambition of great numbers of “Collectors” all over the country’.5 In 1856, Henry Cole came to the conclusion that ‘the taste for collecting’ was now ‘almost universal’, and, by the end of the 1860s, The Graphic, an illustrated political journal, was able to go a step further by claiming that ‘this is the collecting age’.6 During the 1870s, Punch embellished the simple reporting of sales, featuring a number of cartoons of dishevelled and obsessive collectors which developed the idea of ‘mania’. From enthusiastic shoppers to expert connoisseurs, the collecting habit was becoming entrenched in the homes of the Victorian middle classes.

Collecting was by no means confined to the home, however. Alongside the growing number of private collectors was a developing habit of public collecting. The new galleries at South Kensington were part of an emerging network of museums across the country. Inextricably associated with education and enlightenment, with order and stability and self-improvement, these offered a perfect outlet for both civic pride and visible philanthropy. Many wealthy and influential Victorians saw it as nothing less than a public duty to provide spacious, airy galleries where people could learn about art and science, and to construct imposing and stately buildings that reflected the confidence and affluence of their communities. Public collecting was active and fashionable.

Establishing a museum sent a clear message about the aspirations of a town, and the apparent generosity and farsightedness of its leading inhabitants. Those with an eye for boosting local dignity and their own reputations found museums an effective way of securing positive publicity and public support: in Sunderland, the Museum and Library, opened in 1879 by US President Ulysses S. Grant, was largely the work of Robert Cameron, a Member of Parliament, Justice of the Peace and temperance campaigner; in Exeter, it was two MPs, Sir Stafford Northcote of Pynes and Richard Sommers Gard, who proposed and developed the plans for the city’s Albert Memorial Museum. All over the country, those with an interest in municipal matters and affairs of state began to look at ways of developing and displaying public collections that would entertain and inform, and before long a web of museums started to grow across industrial towns and expanding cities, offering more and more people the opportunity to see precious and fascinating things.

Despite their sudden high profile, the emerging museums did not appear completely out of the blue. Many were an extension of local associations such as Mechanics’ Institutes and Literary and Philosophical Societies, established early in the century to encourage and facilitate the research, discussion and display of disciplines as diverse as geology, anatomy and phrenology, shipbuilding, mine engineering, painting and foreign languages. Mechanics’ Institutes varied according to local traditions but, although they ostensibly catered for the working classes, many soon became a means for aspirational white-collar workers to advance themselves while also acting as meeting places for the middle class: the Manchester Guardian claimed in 1849 that of the thirty-two Mechanics’ Institutes in Lancashire and Cheshire only four had any working-class support.7 One of the results of this membership profile was an increasing number of exhibitions. No longer confined to providing practical instruction for workers, a number of committees turned their attention to the arts. In 1839, Leeds Mechanics’ Institute organized an exhibition of ‘arts and manufactures’, while in 1848 Huddersfield described its effort as ‘a polytechnic exhibition on a small scale . . . of pictures and other works of Art and objects of curiosity and interest’.8 Perhaps the most actively enthusiastic of the Institutes was Manchester’s, which organized five exhibitions, the first from December 1837 to February 1838, and the last finishing in the spring of 1845. These eclectic displays included everything from models of steam engines, ships and public buildings, to paintings, phrenology and geological specimens but the first exhibition was typical in also featuring over 400 examples ‘of beautiful manufactures and of Superior workmanship in the Arts’.

By the 1830s and 1840s, most industrial centres, many smaller towns and even some rural villages had a Mechanics’ Institute, generally offering a range of lectures, exhibitions, libraries and specialist classes. The network flourished so rapidly that by 1850 there were over 700 Institutes, boasting more than half a million members.9 Alongside them, many larger cities also had established Literary and Philosophical Societies, often with roots in the eighteenth century. Combining elements of the academic society and the gentleman’s club, they mainly drew their members from among the educated and the influential. But they were not divorced from practical progress and by the 1830s many had evolved into hybrids representing utilitarian, even industrial, interests, while retaining an air of genteel debate. They produced further opportunities for provincial displays, and some even formed collections, often based on a core of natural history objects, with rooms set aside to show everything from prints and paintings to stuffed birds: Newcastle Lit and Phil, for example, opened a special ‘Museum Room’ in 1826 to display the collection of books, manuscripts, prints and natural history specimens which had originally formed the private museum of Marmaduke Tunstall at his home at Wycliffe Hall near Bernard Castle in County Durham, and which the Society had purchased in 1822.