1,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hesperus Press Ltd.

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

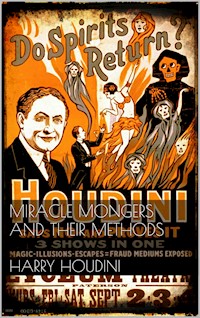

Throughout his life, the world's most famous escapologist strove to expose the methods and tricks of illusionists and sham spiritualists. Studying entertainers and criminals alike, Houdini investigates the tricks of the mind and sleights of hand that have deceived people throughout history. The magician's writings caused a public sensation; legend has it that his book The Right Way to Do Wrong was bought in bulk by burglars in an attempt to guard the tricks of their trade. This collection also includes Houdini's revelations about the methods behind some of his own most famous tricks, and articles he wrote to expose his imitators.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

On Deception

Harry Houdini

Foreword byDerren Brown

‘on’

Published by Hesperus Press Limited

First published 1906–20

This collection first published by Hesperus Press Limited, 2009 Reprinted 2010

This ebook edition first published in 2023

Foreword © Derren Brown, 2009

Designed and typeset by Fraser Muggeridge studio

Printed in Jordan by Jordan National Press

ISBN: 978-1-84391-613-0

E-book ISBN: 978-1-84391-994-0

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Contents

Foreword

Houdini on Houdini

Thieves and Their Tricks

Light on the Subject of Jailbreaking

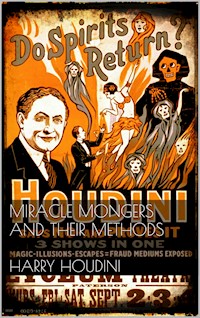

Miracle-Mongers and Their Methods

Biographical note

Foreword

The craft of the magician is to deceive; his art is to lead an audience into a place of wonder by transforming deception into drama. Houdini was the master of dramatic deception: at a time when economic shackles firmly restrained the imagination of his spectators, his symbolic escapes and defiant gestures must have touched upon something deeper than a mere pleasure in being fooled. The greatest magical conceits always seem to have resonated with their times: Selbit’s Sawing In Half of the early 1920s is difficult to separate from the emerging Suffragette movement, the Parisian Grand Guignol theatre of horror which was flourishing in London following the grim shock of the First World War, and the new role of the heroine-in-jeopardy being explored by film and theatre (fashions were changing, too, and it would be easier to bundle the slimmer dress of an Edwardian lady into an illusion box than one of those billowing, hooped parachutes favoured by any Victorian dame hoping to be divided). Dull magic is a collection of tricks: great magic should sting.

The name ‘Houdini’ is synonymous with grand deception, and even the name is not all it seems. Houdini’s real name was Erik Weisz: he took his assumed name from Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, a virtuoso clockmaker and the father of modern magic, a man with whom Harry had a tempestuous relationship. ‘Houdini’ means ‘Of Houdin’. Harry’s temperament sat at odds with the French conjuror’s flair for literary exaggeration (Robert-Houdin’s autobiography The King of the Conjurors is a sensational, semi-fictional romp and one of the greatest autobiographies ever written) and, ego oddly pricked, Houdini devoted much of his time to angrily exposing the ruses employed by his former hero.

Why should a magician wish to expose another’s deceptions? It is an odd tendency, still rife amongst magicians today. The false displays of power and ludicrous posturing associated with the magician – generally at heart a lonely type who resorted to tricks at a young age to compensate for a lack of social confidence – do not sit well with encouraging a spectator’s astonishment at a fellow (and potentially ‘rival’) magician. Rather than nurture the layman’s delight in a successful illusion, and therefore celebrate the wonder and impossibility of it all (which ultimately helps all magicians), the preference amongst most conjurors is to immediately let it be known that they themselves can produce the same feat; that it is far easier than it appears; that the magician in question is really not quite as talented as he might have appeared. In a profession where appearance and misjudgement are the principal currencies, this is rather a bizarre and shameful tendency, though perhaps understandable given the kind of flatulent ego needed to pose as a miracle worker in the first place. For those in doubt, read the pages that follow: this book is full of bitter self-aggrandising and petty point-scoring from probably the greatest magician who ever lived.

There is, at least, an unspoken contract between magician and audience, according to which deception is both allowed and expected. In other areas, artful deception is practised without such a contract, such as that of the fraudulent psychic or medium, whom Houdini attacks vociferously in other works. The loss of his own mother, to whom Harry felt enormously close (he says, perhaps a little self-consciously, in these pages that he never travelled to Australia because he could not bear to be so far from her), and the fraud and failure he discovered while attempting to reach her through mediumistic channels, again lent the sharp sting of bitterness to his crusade to publicly expose those mediums deceiving the public. The mediums of the time were far more noteworthy than the limply unpleasant cold-readers known to us through television and radio today. The rational, scientific agenda of the Enlightenment had left a gap for the arcane and spiritual to flourish, while still demanding ‘evidence’ from those offering new paths to knowledge. Hence, the popular mediums of the latter half of the nineteenth century both found their lacuna in society and were obliged to produce physical ‘proof’ of the spirit contact they promised. For many years, tables levitated in the lightless séance room, spirit hands and ectoplasm drifted through the darkness, until the use of infra-red photography exposed the tricks of the mediums and their ‘evidence’ gradually shifted to the purely verbal illusions and dodges of the modern practitioners. This lack of physical ‘proofs’ of the modern medium has made the frauds more difficult to expose, and has most likely brought about far more well-intentioned psychics who do not consciously deceive at all, but instead honestly come to believe in their own professed powers. The capacity for self-deception, rarely acknowledged or understood by those who offer us supernatural answers to our problems, is huge: as easy as it is to make a medium’s cold-reading statements ‘fit’ our own situation and come to believe that he must have some paranormal insight, it is hardly any more difficult for a would-be psychic with an average ego, upon hearing frequently positive feedback, to believe over time that he must be blessed with a special gift. It’s harder to think you’re doing it for real when you’re tossing tambourines in the dark or have ready-made ectoplasm stuffed into your mouth or bottom.

The psychic has no contract with the audience that permits conscious fraud; the stage or close-up conjuror generally has a clear contract that permits all deception to take place to produce the final effect; the mind-reader or escapologist exists between the two and decides for himself how honest he wishes to be with his audience. The mind-reader frequently offers a nervous disclaimer – ‘Everything you see is for entertainment only and I make no psychic claims’ – generally this is no more than a reluctant legal get-out clause, as generally seen flashed up on the screen at the end of the shows of television psychics, but its message may be lost in the quite contradictory implications of the act itself. Escapologists such as Houdini also employ deception, usually cartloads of it, but as the misleading of the public is less worrisome than with a medium, the issue is perhaps an artistic choice rather than a moral concern. But even with magicians, in whose case we expect to see (or, strictly speaking, not see) deception at work, we might feel that some contract of trust had been broken were we to find out that what was being presented as a card-sharp demonstration of virtuosic centre-deals and card-control was in fact an easy trick accomplished by far more mundane methods such as duplicate cards and so on. In a profession inextricable from deceit and whose end purpose is entertainment, there are no easy resolutions to these questions, and performers argue endlessly amongst themselves over what level of deception is permissible.

To all magicians (save perhaps those engrossed in the early career stages of mastering sleight-of-hand), the best deceptions are the biggest and boldest. Houdini betrays this delight in such stratagems when he talks with barely disguised admiration of the grand confidence tricks pulled off by some of the great characters described in these pages. The balls, the chutzpah, the gall, nerve and impudence of the successful lie that is huge enough to never be questioned is always a source of immense professional pleasure amongst magicians with any sense of the theatrical. And given that there is often a dose of envy bubbling within the moral outrage held by any one group for another, Houdini’s famous pursuit of fraudsters is probably inseparable from a guilty resentment of their ability to masquerade and dissemble without limit.

To most of the audience, there is a delight in being fooled, and a granted unspoken licence for the magician to play the part of the mysterious wonder-worker we know he cannot be. This licence runs out when the magician becomes too enamoured with the role we have, as audience, allowed him to play. Unable to express his joy at the truly fascinating employments of misdirection and gimmickry that have secured his feats, the would-be Svengali must posture vacuously in order to secure the interest of his public. Stunts may become more self-aggrandising, public claims more ludicrous and the pretensions of a manufactured personality may start to grate. Part of the success of the modern duo Penn & Teller is that they have avoided playing the whimsical god role, which, as Teller has eloquently pointed out, is far less interesting than the contrasting figure of the very human, struggling hero. Deception alone has a limited shelf-life in terms of maintaining public enjoyment: replacing ego with an understanding of character, drama and what an audience wants is necessary for lasting popularity. Penn & Teller, now fifty-four and sixty respectively, are every bit as cool and fresh as they were when they became well known in the 1980s. Their recent, vociferous, highly successful Bullshit! series, exposing modern frauds from mediums to penis-enlargement schemes, would have made Houdini proud.