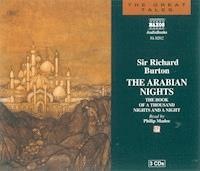

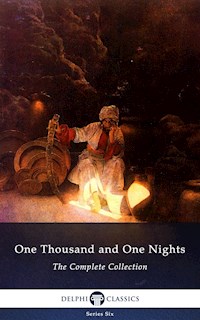

One Thousand and One Nights - Complete Arabian Nights Collection (Delphi Classics) E-Book

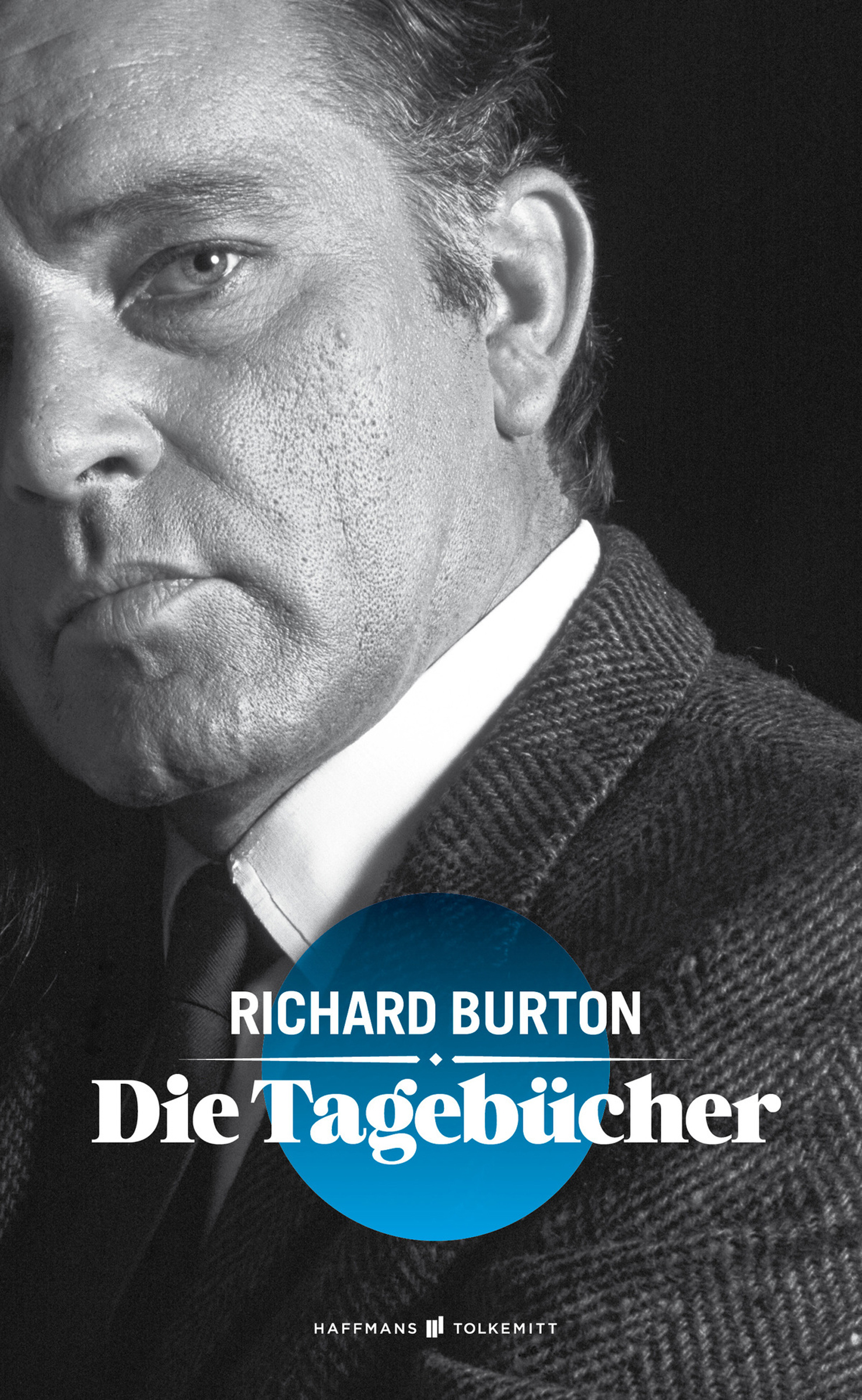

Richard Burton

2,73 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Delphi Classics

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Series Six

- Sprache: Englisch

The exotic tales of the Arabian Nights have charmed and delighted readers across the world for almost a millennia. The collection features hundreds of magical Middle Eastern and Indian stories, including the famous first appearances of Aladdin, Ali Baba and Sindbad the Sailor. This eBook presents a comprehensive collection of translations of ‘One Thousand and One Nights’, with numerous illustrations, rare texts, informative introductions and the usual Delphi bonus material. (Version 1)

* Beautifully illustrated with images relating to ‘One Thousand and One Nights’

* Concise introductions to the translations

* 5 different translations, with individual contents tables

* Features Burton’s seminal 16 volume translation

* Excellent formatting of the texts

* Some tales are illustrated with their original artwork

* Features Edward William Lane’s guide to ARABIAN SOCIETY IN THE MIDDLE AGES – the perfect accompaniment to reading ‘One Thousand and One Nights’

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to browse through our range of exciting titles

CONTENTS:

The Translations

ONE THOUSAND AND ONE NIGHTS

JONATHAN SCOTT 1811 TRANSLATION

JOHN PAYNE 1884 TRANSLATION

RICHARD FRANCIS BURTON 1885 TRANSLATION

ANDREW LANG 1885 TRANSLATION

JULIA PARDOE 1857 ADAPTATION

The Guide

ARABIAN SOCIETY IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Edward William Lane

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to browse through our range of exciting titles or to purchase this eBook as a Parts Edition of individual eBooks

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 24057

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The Complete Collection

ONE THOUSAND AND ONE NIGHTS

(c.700-900)

Contents

The Translations

ONE THOUSAND AND ONE NIGHTS

JONATHAN SCOTT 1811 TRANSLATION

JOHN PAYNE 1884 TRANSLATION

RICHARD FRANCIS BURTON 1885 TRANSLATION

ANDREW LANG 1885 TRANSLATION

JULIA PARDOE 1857 ADAPTATION

The Guide

ARABIAN SOCIETY IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Edward William Lane

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2015

Version 1

The Complete Collection

ONE THOUSAND AND ONE NIGHTS

By Delphi Classics, 2015

COPYRIGHT

One Thousand and One Nights - Complete Collection

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

Parts Edition Now Available!

Love reading The Arabian Nights?

Did you know you can now purchase the Delphi Classics Parts Edition of this author and enjoy all the novels, plays, non-fiction books and other works as individual eBooks? Now, you can select and read individual novels etc. and know precisely where you are in an eBook. You will also be able to manage space better on your eReading devices.

The Parts Edition is only available direct from the Delphi Classics website.

For more information about this exciting new format and to try free Parts Edition downloads, please visit this link.

The Translations

A manuscript of the ‘One Thousand and One Nights’

An artistic portrayal of a city from the ‘One Thousand and One Nights’

ONE THOUSAND AND ONE NIGHTS

This famous collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales was compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age and is often known in English as the Arabian Nights, due to the 1706 first English language edition being titled The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. The tales were collected over many centuries by various authors, translators and scholars across West, Central and South Asia and North Africa, revealing influences from ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian and Egyptian literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most likely drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān, which in turn relied partly on Indian elements.

The stories are connected by the frame story concerning the ruler Shahryār (Persian for “king”) and his wife Scheherazade (Persian for “of noble lineage”), while other tales are introduced within the frame story by its characters. Some editions of One Thousand and One Nights contain only a few hundred nights’ tales, while others include 1,001 or even more. The majority of the text is written in prose, though verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.

The main frame story introduces Shahryar, whom the narrator calls a “Sasanian king” ruling in “India and China”, who is shocked to discover that his brother’s wife has been unfaithful. Discovering that his own wife’s infidelity has been even more flagrant, he has her executed and in his bitterness and grief decides that all women are the same. Shahryar begins to marry a succession of virgins only to execute each one the next morning, before she has a chance to dishonour him. Eventually, the vizier, whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins. Devising a cunning plan, Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees. On the night of their marriage, Scheherazade begins to tell the king a tale, but does not end it. The king, curious about how the story will end, is thus forced to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. The next night, as soon as she finishes the tale, she begins a new one, before pausing for the night, Eager to hear the conclusion, the king postpones her execution once again and so the pattern continues for a total of 1,001 nights.

The Arabian Nights tales vary widely, including historical tales, love stories, tragedies, comedies, poems, burlesques and various forms of erotica. Numerous stories depict jinns, ghouls, apes, sorcerers, magicians and legendary places, which are often intermingled with real-life people and geographical locations, though not always rationally. Typical protagonists include the historical Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, his Grand Vizier, Jafar al-Barmaki and the famous poet Abu Nuwas, despite the fact that these figures lived some 200 years after the fall of the Sassanid Empire in which the frame tale of Scheherazade is set. Sometimes a character in Scheherazade’s tale will begin telling other characters a story of his own, and that story may have another one told within it, resulting in a richly layered narrative texture.

Devices found in Sanskrit literature, including the use of frame stories and animal fables, have been identified by some scholars as lying at the root of the conception of the One Thousand and One Nights collection. Indian folklore is represented by certain animal stories, reflecting influence from ancient Sanskrit fables, while the influence of the Panchatantra and Baital Pachisi is particularly notable. The Jataka Tales are a collection of 547 Buddhist stories, which are for the most part moral stories with an ethical purpose.

The first European version (1704–1717) was translated into French by Antoine Galland from an Arabic text of the Syrian recension and other sources. The twelve volume work, Les Mille et une nuits, contes arabes traduits en français (Thousand and one nights, Arab stories translated into French), included stories that were not in the original Arabic manuscript. Aladdin’s Lamp and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, as well as several other, lesser known tales, actually appeared first in Galland’s translation and cannot be found in any of the original manuscripts of the collection. Galland recorded that he heard them from a Syrian Christian storyteller from Aleppo, a Maronite scholar whom he called “Hanna Diab.” Galland’s version of the One Thousand and One Nights proved to be so popular throughout Europe that later versions were issued by his publisher using Galland’s name without his consent.

As scholars were looking for the presumed “complete” and “original” form of the One Thousand and One Nights, they naturally turned to the more voluminous texts of the Egyptian recension, which soon came to be viewed as the standard version. The first translations of this kind, such as that published by Edward Lane (1840, 1859), were bowdlerized. Unabridged and unexpurgated translations were made, first by John Payne, under the title The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (1882, nine volumes), and then by Sir Richard Francis Burton, entitled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885, ten volumes).

Another manuscript of ‘One Thousand and One Nights’ dating back to the 14th century

Queen Scheherazade, as painted in the 19th century by Sophie Anderson

Scheherazade and Shahryār by Ferdinand Keller, 1880

‘The story of Princess Parizade and the Magic Tree’ by Maxfield Parrish

‘Sindbad and the Valley of Diamonds, from the Second Voyage’ by Maxfield Parrish

‘The Story Of The Magic Horse’ by Maxfield Parrish

JONATHAN SCOTT 1811 TRANSLATION

Jonathan Scott (1754–1829) was an English orientalist, best known for the following translation of the One Thousand and One Nights. In 1802 Scott was appointed professor of oriental languages at the Royal Military College, but resigned that post in 1805. He held, about the same time, a similar position at the East India College at Haileybury. In 1805 the honorary degree of D.C.L. was conferred upon him by the University of Oxford in recognition of his attainments in oriental literature.

In 1811 Scott published his edition of the Arabian Nights Entertainments, after his friend Edward Wortley Montagu had brought back from Turkey a nearly complete manuscript of the work (now in the Bodleian Library), composed in 1764. Scott proposed to make a fresh translation from this manuscript, and printed a description of it, together with a table of contents, in William Ouseley’s Oriental Collection. He abandoned the idea later on, and contented himself with revising Antoine Galland’s French version (1704–1717), saying that he found it so correct that it would be pointless to go over the original again. He prefixed a copious introduction, and added some additional tales from other sources. The work was the earliest effort to render the Arabian Nights into literary English and was commercially popular, being republished in London in 1882 and again in 1890.

CONTENTS

VOLUME 1

THE PUBLISHERS’ PREFACE.

It is upon this text that the present edition is formed.

The Arabian Nights Entertainments.

The Ass, the Ox, and the Labourer.

THE MERCHANT AND THE GENIE.

The Story of the First Old Man and the Hind.

The Story of the Second old Man and the Two Black Dogs.

THE STORY OF THE FISHERMAN.

The Story of the Grecian King and the Physician Douban.

The Story of the Husband and the Parrot.

The Story of the Vizier that was Punished.

The History of the Young King of the Black Isles.

STORY OF THE THREE CALENDERS, SONS OF SULTANS; AND OF THE FIVE LADIES OF BAGDAD.

The History of the First Calender.

The Story of the Second Calender.

The Story of the Envious Man, and of him that he Envied.

The History of the Third Calender.

The Story of Zobeide.

The Story of Amene.

THE STORY OF SINBAD THE VOYAGER.

The First Voyage.

The Second Voyage.

The Third Voyage.

The Fourth Voyage.

The Fifth Voyage.

The Sixth Voyage.

The Seventh and Last Voyage.

THE THREE APPLES.

The Story of Noor ad Deen Ali and Buddir ad Deen Houssun.

Another was served up to the eunuch, and he gave the same judgment.

THE HISTORY OF GANEM, SON OF ABOU AYOUB, AND KNOWN BY THE SURNAME OF LOVE’S SLAVE.

VOLUME 2

THE STORY OF THE LITTLE HUNCH-BACK.

The Story told by the Christian Merchant.

The Story told by the Sultan of Casgar’s Purveyor.

The Story told by the Jewish Physician.

The Story told by the Tailor.

The Story of the Barber.

The Story of the Barber’s Eldest Brother.

The Story of the Barber’s Second Brother.

The Story of the Barber’s Third Brother.

The Story of the Barber’s Fourth Brother.

The Story of the Barber’s Fifth Brother.

The Story of the Barber’s Sixth Brother.

Letter from Schemselnihar to the Prince of Persia.

The Prince of Persia’s Answer to Schemselnihar’s Letter.

Letter from Schemselnihar to the Prince of Persia.

The Prince of Persia’s Answer to Schemselnihar.

The Story of the Princes Amgiad and Assad.

THE STORY OF NOOR AD DEEN AND THE FAIR PERSIAN.

VOLUME 3

THE STORY OF BEDER, PRINCE OF PERSIA, AND JEHAUN-ARA, PRINCESS OF SAMANDAL, OR SUMMUNDER.

THE HISTORY OF PRINCE ZEYN ALASNAM AND THE SULTAN OF THE GENII.

THE HISTORY OF CODADAD, AND HIS BROTHERS.

The History of the Princess of Deryabar.

THE STORY OF ABOU HASSAN, OR THE SLEEPER AWAKENED.

THE STORY OF ALLA AD DEEN; OR, THE WONDERFUL LAMP.

ADVENTURE OF THE CALIPH HAROON AL RUSHEED.

The Story of Baba Abdoollah.

The Story of Syed Naomaun.

The Story of Khaujeh Hassan al Hubbaul.

THE STORY OF ALI BABA AND THE FORTY ROBBERS DESTROYED BY A SLAVE.

THE STORY OF ALI KHAUJEH, A MERCHANT OF BAGDAD.

VOLUME 4

THE STORY OF THE ENCHANTED HORSE.

THE STORY OF PRINCE AHMED, AND THE FAIRY PERIE BANOU.

THE STORY OF THE SISTERS WHO ENVIED THEIR YOUNGER SISTER.

STORY OF THE SULTAN OF YEMEN AND HIS THREE SONS.

STORY OF THE THREE SHARPERS AND THE SULTAN.

The Adventures of the Abdicated Sultan.

History of Mahummud, Sultan of Cairo.

Story of the First Lunatic.

Story of the Second Lunatic.

Story of the Broken-backed Schoolmaster.

Story of the Wry-mouthed Schoolmaster.

Story of the Sisters and the Sultana their Mother.

STORY OF THE BANG-EATER AND THE CAUZEE.

Story of the Bang-eater and His Wife.

THE SULTAN AND THE TRAVELLER MHAMOOD AL HYJEMMEE.

The Koord Robber.

Story of the Husbandman.

Story of the Three Princes and Enchanting Bird.

Story of a Sultan of Yemen and his three Sons.

Story of the First Sharper in the Cave.

History of the Sultan of Hind.

STORY OF THE FISHERMAN’S SON.

STORY OF ABOU NEEUT AND ABOU NEEUTEEN; OR, THE WELL-INTENTIONED AND THE DOUBLE-MINDED.

ADVENTURE OF A COURTIER, RELATED BY HIMSELF TO HIS PATRON, AN AMEER OF EGYPT.

STORY OF THE PRINCE OF SIND, AND FATIMA, DAUGHTER OF AMIR BIN NAOMAUN.

STORY OF THE LOVERS OF SYRIA; OR, THE HEROINE.

STORY OF HYJAUJE, THE TYRANNICAL GOVERNOR OF COUFEH, AND THE YOUNG SYED.

STORY OF INS AL WUJJOOD AND WIRD AL IKMAUM, DAUGHTER OF IBRAHIM, VIZIER TO SULTAN SHAMIKH.

THE ADVENTURES OF MAZIN OF KHORASSAUN.

STORY OF THE SULTAN, THE DERVISH, AND THE BARBER’S SON.

ADVENTURES OF ALEEFA, DAUGHTER OF MHEREJAUN, SULTAN OF HIND, AND EUSUFF, SON OF SOHUL, SULTAN OF SIND.

ADVENTURES OF THE THREE PRINCES, SONS OF THE SULTAN OF CHINA.

STORY OF THE GOOD VIZIER UNJUSTLY IMPRISONED.

STORY OF THE LADY OF CAIRO AND HER FOUR GALLANTS.

The Cauzee’s Story.

STORY OF THE MERCHANT, HIS DAUGHTER, AND THE PRINCE OF EERAUK.

ADVENTURES OF THE CAUZEE, HIS WIFE, &c.

The Sultan’s Story of Himself.

CONCLUSION.

VOLUME 1

THE PUBLISHERS’ PREFACE.

This, the “Aldine Edition” of “The Arabian Nights Entertainments,” forms the first four volumes of a proposed series of reprints of the Standard works of fiction which have appeared in the English language.

It is our intention to publish the series in an artistic way, well illustrating a text typographically as perfect as possible. The texts in all cases will be carefully chosen from approved editions.

The series is intended for those who appreciate well printed and illustrated books, or who are in want of a handy and handsome edition of such works to place upon their bookshelves.

The exact origin of the Tales, which appear in the Arabic as “The Thousand and One Nights,” is unknown. The Caliph Haroon al Rusheed, who, figures in so lifelike a manner in many of the stories, was a contemporary of the Emperor Charlemagne, and there is internal evidence that the collection was made in the Arabic language about the end of the tenth century.

They undoubtedly convey a picturesque impression of the manners, sentiments, and customs of Eastern Mediaeval Life.

The stories were translated from the Arabic by M. Galland and first found their way into English in 1704, when they were retranslated from M. Galland’s French text and at once became exceedingly popular.

This process of double translation had great disadvantages; it induced Dr. Jonathan Scott, Oriental Professor, to publish in 1811, a new edition, revised and corrected from the Arabic.

It is upon this text that the present edition is formed.

It will be found free from that grossness which is unavoidable in a strictly literal translation of the original into English; and which has rendered the splendid translations of Sir R. Burton and Mr. J. Payne quite unsuitable as the basis of a popular edition, though at the same time stamping the works as the two most perfect editions for the student.

The scholarly translation of Lane, by the too strict an adherence to Oriental forms of expression, and somewhat pedantic rendering of the spelling of proper names, is found to be tedious to a very large number of readers attracted by the rich imagination, romance, and humour of these tales.

The Arabian Nights Entertainments.

The chronicles of the Sassanians, ancient kings of Persia, who extended their empire into the Indies, over all the adjacent islands, and a great way beyond the Ganges, as far as China, acquaint us, that there was formerly a king of that potent family, who was regarded as the most excellent prince of his time. He was as much beloved by his subjects for his wisdom and prudence, as he was dreaded by his neighbours, on account of his velour, and well-disciplined troops. He had two sons; the elder Shier-ear, the worthy heir of his father, and endowed with all his virtues; the younger Shaw-zummaun, a prince of equal merit.

After a long and glorious reign, this king died; and Shier-ear mounted his throne. Shaw-zummaun, being excluded from all share in the government by the laws of the empire, and obliged to live a private life, was so far from envying the happiness of his brother, that he made it his whole business to please him, and in this succeeded without much difficulty. Shier-ear, who had naturally a great affection the prince his brother, gave him the kingdom of Great Tartary. Shaw-zummaun went immediately and took possession of it, and fixed the seat of his government at Samarcand, the metropolis of the country.

After they had been separated ten years, Shier-ear, being very desirous of seeing his brother, resolved to send an ambassador to invite him to his court. He made choice of his prime vizier for the embassy, and sent him to Tartary, with a retinue answerable to his dignity. The vizier proceeded with all possible expedition to Samarcand. When he came near the city, Shaw-zummaun was informed of his approach, and went to meet him attended by the principal lords of his court, who, to shew the greater honour to the sultan’s minister, appeared in magnificent apparel. The king of Tartary received the ambassador with the greatest demonstrations of joy; and immediately asked him concerning the welfare of the sultan his brother. The vizier having acquainted him that he was in health, informed him of the purpose of his embassy. Shaw-zummaun was much affected, and answered: “Sage vizier, the sultan my brother does me too much honour; nothing could be more agreeable to me, for I as ardently long to see him as he does to see me. Time has not diminished my friendship more than his. My kingdom is in peace, and I want no more than ten days to get myself ready to return with you. There is therefore no necessity for your entering the city for so short a period. I pray you to pitch your tents here, and I will order everything necessary to be provided for yourself and your attendants.” The vizier readily complied; and as soon as the king returned to the city, he sent him a prodigious quantity of provisions of all sorts, with presents of great value.

In the meanwhile, Shaw-zummaun prepared for his journey, gave orders about his most important affairs, appointed a council to govern in his absence, and named a minister, of whose wisdom he had sufficient experience, and in whom he had entire confidence, to be their president. At the end of ten days, his equipage being ready, he took leave of the queen his wife, and went out of town in the evening with his retinue. He pitched his royal pavilion near the vizier’s tent, and conversed with him till midnight. Wishing once more to see the queen, whom he ardently loved, he returned alone to his palace, and went directly to her majesty’s apartments. But she, not expecting his return, had taken one of the meanest officers of her household to her bed.

The king entered without noise, and pleased himself to think how he should surprise his wife who he thought loved him with reciprocal tenderness. But how great was his astonishment, when, by the light of the flambeau, he beheld a man in her arms! He stood immovable for some time, not knowing how to believe his own eyes. But finding there was no room for doubt, “How!” said he to himself, “I am scarcely out of my palace, and but just under the walls of Samarcand, and dare they put such an outrage upon me? Perfidious wretches! your crime shall not go unpunished. As a king, I am bound to punish wickedness committed in my dominions; and as an enraged husband, I must sacrifice you to my just resentment.” The unfortunate prince, giving way to his rage, then drew his cimeter, and approaching the bed killed them both with one blow, their sleep into death; and afterwards taking them up, he threw them out of a window into the ditch that surrounded the palace.

Having thus avenged himself, he returned to his pavilion without saying one word of what had happened, gave orders that the tents should be struck, and everything made ready for his journey. All was speedily prepared, and before day he began his march, with kettle-drums and other instruments of music, that filled everyone with joy, excepting the king; he was so much afflicted by the disloyalty of his wife, that he was seized with extreme melancholy, which preyed upon his spirits during the whole of his journey.

When he drew near the capital of the Indies, the sultan Shier-ear and all his court came out to meet him. The princes were overjoyed to see one another, and having alighted, after mutual embraces and other marks of affection and respect, remounted, and entered the city, amidst the acclamations of the people. The sultan conducted his brother to the palace provided for him, which had a communication with his own by a garden. It was so much the more magnificent as it was set apart as a banqueting-house for public entertainments, and other diversions of the court, and its splendour had been lately augmented by new furniture.

Shier-ear immediately left the king of Tartary, that he might give him time to bathe, and to change his apparel. As soon as he had done, he returned to him again, and they sat down together on a sofa or alcove. The courtiers out of respect kept at a distance, and the two princes entertained one another suitably to their friendship, their consanguinity, and their long separation. The time of supper being come, they ate together, after which they renewed their conversation, which continued till Shier-ear, perceiving that it was very late, left his brother to repose.

The unfortunate Shaw-zummaun retired to bed. Though the conversation of his brother had suspended his grief for some time, it returned again with increased violence; so that, instead of taking his necessary rest, he tormented himself with the bitterest reflections. All the circumstances of his wife’s disloyalty presented themselves afresh to his imagination, in so lively a manner, that he was like one distracted being able to sleep, he arose, and abandoned himself to the most afflicting thoughts, which made such an impression upon his countenance, as it was impossible for the sultan not to observe. “What,” said he, “can be the matter with the king of Tartary that he is so melancholy? Has he any cause to complain of his reception? No, surely; I have received him as a brother whom I love, so that I can charge myself with no omission in that respect. Perhaps it grieves him to be at such a distance from his dominions, or from the queen his wife? If that be the case, I must forthwith give him the presents I designed for him, that he may return to Samarcand.” Accordingly the next day Shier-ear sent him part of those presents, being the greatest rarities and the richest things that the Indies could afford. At the same time he endeavoured to divert his brother every day by new objects of pleasure, and the most splendid entertainments. But these, instead of affording him ease, only increased his sorrow.

One day, Shier-ear having appointed a great hunting-match, about two days journey from his capital, in a place that abounded with deer, Shaw-zummaun besought him to excuse his attendance, for his health would not allow him to bear him company. The sultan, unwilling to put any constraint upon him, left him at his liberty, and went a-hunting with his nobles. The king of Tartary being thus left alone, shut himself up in his apartment, and sat down at a window that looked into the garden. That delicious place, and the sweet harmony of an infinite number of birds, which chose it for their retreat, must certainly have diverted him, had he been capable of taking pleasure in anything; but being perpetually tormented with the fatal remembrance of his queen’s infamous conduct, his eyes were not so much fixed upon the garden, as lifted up to heaven to bewail his misfortune.

While he was thus absorbed in grief, a circumstance occurred which attracted the whole of his attention. A secret gate of the sultan’s palace suddenly opened, and there came out of it twenty women, in the midst of whom walked the sultaness, who was easily distinguished from the rest by her majestic air. This princess thinking that the king of Tartary was gone a-hunting with his brother the sultan, came with her retinue near the windows of his apartment. For the prince had so placed himself that he could see all that passed in the garden without being perceived himself. He observed, that the persons who accompanied the sultaness threw off their veils and long robes, that they might be more at their ease, but he was greatly surprised to find that ten of them were black men, and that each of these took his mistress. The sultaness, on her part, was not long without her gallant. She clapped her hands, and called “Masoud, Masoud,” and immediately a black descended from a tree, and ran towards her with great speed.

Modesty will not allow, nor is it necessary, to relate what passed between the blacks and the ladies. It is sufficient to say, that Shaw-zummaun saw enough to convince him, that his brother was as much to be pitied as himself. This amorous company continued together till midnight, and having bathed together in a great piece of water, which was one of the chief ornaments of the garden, they dressed themselves, and re-entered the palace by the secret door, all except Masoud, who climbed up his tree, and got over the garden wall as he had come in.

These things having passed in the king of Tartary’s sight, filled him with a multitude of reflections. “How little reason had I,” said he, “to think that none was so unfortunate as myself? It is surely the unavoidable fate of all husbands, since even the sultan my brother, who is sovereign of so-many dominions, and the greatest prince of the earth, could not escape. Such being the case, what a fool am I to kill myself with grief? I am resolved that the remembrance of a misfortune so common shall never more disturb my peace.”

From that moment he forbore afflicting himself. He called for his supper, ate with a better appetite than he had done since his leaving Samarcand, and listened with some degree of pleasure to the agreeable concert of vocal and instrumental music that was appointed to entertain him while at table.

He continued after this very cheerful; and when he was informed that the sultan was returning, went to meet him, and paid him his compliments with great gaiety. Shier-ear at first took no notice of this alteration. He politely expostulated with him for not bearing him company, and without giving him time to reply, entertained him with an account of the great number of deer and other game they had killed, and the pleasure he had received in the chase. Shaw-zummaun heard him with attention; and being now relieved from the melancholy which had before depressed his spirits, and clouded his talents, took up the conversation in his turn, and spoke a thousand agreeable and pleasant things to the sultan.

Shier-ear, who expected to have found him in the same state as he had left him, was overjoyed to see him so cheerful: “Dear brother,” said he, “I return thanks to heaven for the happy change it has wrought in you during my absence. I am indeed extremely rejoiced. But I have a request to make to you, and conjure you not to deny me.” “I can refuse you nothing,” replied the king of Tartary; “you may command Shaw-zummaun as you please: speak, I am impatient to know what you desire of me.” “Ever since you came to my court,” resumed Shier-ear, “I have found you immersed in a deep melancholy, and I have in vain attempted to remove it by different diversions. I imagined it might be occasioned by your distance from your dominions, or that love might have a great share in it; and that the queen of Samarcand, who, no doubt, is an accomplished beauty, might be the cause. I do not know whether I am mistaken in my conjecture; but I must own, that it was for this very reason I would not importune you upon the subject, for fear of making you uneasy. But without myself contributing anything towards effecting the change, I find on my return that your mind is entirely delivered from the black vapour which disturbed it. Pray do me the favour to tell me why you were so melancholy, and wherefore you are no longer so.”

The king of Tartary continued for some time as if he had been meditating and contriving what he should answer; but at last replied, “You are my sultan and master; but excuse me, I beseech you, from answering your question.” “No, dear brother,” said the sultan, “you must answer me, I will take no denial.” Shaw-zummaun, not being able to withstand these pressing entreaties, replied, “Well then, brother, I will satisfy you, since you command me;” and having told him the story of the queen of Samarcand’s treachery “This,” said he, “was the cause of my grief; judge whether I had not sufficient reason for my depression.”

“O! my brother,” said the sultan, (in a tone which shewed what interest he took in the king of Tartary’s affliction), “what a horrible event do you tell me! I commend you for punishing the traitors who offered you such an outrage. None can blame you for what you have done. It was just; and for my part, had the case been mine, I should scarcely have been so moderate. I could not have satisfied myself with the life of one woman; I should have sacrificed a thousand to my fury. I now cease to wonder at your melancholy. The cause was too afflicting and too mortifying not to overwhelm you. O heaven! what a strange adventure! Nor do I believe the like ever befell any man but yourself. But I must bless God, who has comforted you; and since I doubt not but your consolation is well-grounded, be so good as to inform me what it is, and conceal nothing from me.” Shaw-zummaun was not so easily prevailed upon in this point as he had been in the other, on his brother’s account. But being obliged to yield to his pressing instances, answered, “I must obey you then, since your command is absolute, yet I am afraid that my obedience will occasion your trouble to be greater than my own. But you must blame yourself, since you force me to reveal what I should otherwise have buried in eternal Oblivion.” “What you say,” answered Shier-ear, “serves only to increase my curiosity. Discover the secret, whatever it be.” The king of Tartary being no longer able to refuse, related to him the particulars of the blacks in disguise, of the ungoverned passion of the sultaness, and her ladies; nor did he forget Masoud. After having been witness to these infamous actions, he continued, “I believed all women to be naturally lewd; and that they could not resist their inclination. Being of this opinion, it seemed to me to be in men an unaccountable weakness to place any confidence in their fidelity. This reflection brought on many others; and in short, I thought the best thing I could do was to make myself easy. It cost me some pains indeed, but at last I grew reconciled; and if you will take my advice, you will follow my example.”

Though the advice was good, the sultan could not approve of it, but fell into a rage. “What!” said he, “is the sultaness of the Indies capable of prostituting herself in so base a manner! No, brother, I cannot believe what you state unless I beheld it with my own eyes. Yours must needs have deceived you; the matter is so important that I must be satisfied of it myself.” “Dear brother,” answered Shaw-zummaun, “that you may without much difficulty. Appoint another hunting-match, and when we are out of town with your court and mine, we will rest under our tents, and at night let you and I return unattended to my apartments. I am certain the next day you will see a repetition of the scene.” The sultan approving the stratagem, immediately appointed another hunting-match. And that same day the tents were pitched at the place appointed.

The next day the two princes set out with all their retinue; they arrived at the place of encampment, and stayed there till night. Shier-ear then called his grand vizier, and, without acquainting him with his design, commanded him during his absence to suffer no person to quit the camp on any presence whatever. As soon as he had given this order, the king of Grand Tartary and he took horse, passed through the camp incognito, returned to the city, and went to Shaw-zummaun’s apartment. They had scarcely placed themselves in the window whence the king of Tartary had beheld the scene of the disguised blacks, when the secret gate opened, the sultaness and her ladies entered the garden with the blacks, and she having called to Masoud, the sultan saw more than enough fully to convince him of his dishonour and misfortune.

“Oh heavens!” he exclaimed, “what indignity! What horror! Can the wife of a sovereign be capable of such infamous conduct? After this, let no prince boast of being perfectly happy. Alas! my brother,” continued he, embracing the king of Tartery, “let us both renounce the world, honour is banished out of it; if it flatter us one day, it betrays us the next. Let us abandon our dominions, and go into foreign countries, where we may lead an obscure life, and conceal our misfortunes.” Shaw-zummaun did not at all approve of this plan, but did not think fit to contradict Shierear in the heat of his passion. “Dear brother,” he replied, “your will shall be mine. I am ready to follow you whithersoever you please: but promise me that you will return, if we meet with any one more unhappy than ourselves.” “To this I agree,” said the sultan, “but doubt much whether we shall.” “I am not of your opinion in this,” replied the king of Tartary; “I fancy our journey will be but short.” Having thus resolved, they went secretly out of the palace. They travelled as long as day-light continued; and lay the first night under trees. They arose about break of day, went on till they came to a fine meadow on the seashore, that was be-sprinkled with large trees They sat down under one of them to rest and refresh themselves, and the chief subject of their conversation was the infidelity or their wives.

They had not rested long, before they heard a frightful noise from the sea, and a terrible cry, which filled them with fear. The sea then opened, and there arose something like a great black column, which reached almost to the clouds. This redoubled their terror, made them rise with haste, and climb up into a tree to bide themselves. They had scarcely got up, when looking to the place from whence the noise proceeded, and where the sea had opened, they observed that the black column advanced, winding about towards the shore, cleaving the water before it. They could not at first think what this could mean, but in a little time they found that it was one of those malignant genies that are mortal enemies to mankind, and are always doing them mischief. He was black and frightful, had the shape of a giant, of a prodigious stature, and carried on his head a large glass box, fastened with four locks of fine steel. He entered the meadow with his burden, which he laid down just at the foot of the tree where the two princes were concealed, who gave themselves over as lost. The genie sat down by his box, and opening it with four keys that he had at his girdle, there came out a lady magnificently appareled, of a majestic stature, and perfect beauty. The monster made her sit down by him, and eyeing her with an amorous look, said, “Lady, nay, most accomplished of all ladies who are admired for their beauty, my charming mistress, whom I carried off on your wedding-day, and have loved so constantly ever since, let me sleep a few moments by you; for I found myself so very drowsy that I came to this place to take a little rest.” Having spoken thus, he laid down his huge head upon the lady’s knees, and stretching out his legs, which reached as far as the sea, he fell asleep presently, and snored so loud that he made the shores echo.

The lady happening at this time to look up, saw the two princes in the tree, and made a sign to them with her hand to come down without making any noise. Their fear was extreme when they found themselves discovered, and they prayed the lady, by other signs, to excuse them. But she, after having laid the monster’s head softly on the ground, rose up and spoke to them, with a low but eager voice, to come down to her; she would take no denial. They informed her by signs that they were afraid of the genie, and would fain have been excused. Upon which she ordered them to come down, and threatened if they did not make haste, to awaken the genie, and cause him to put them to death.

These words so much intimidated the princes, that they began to descend with all possible precaution lest they should awake the genie. When they had come down, the lady took them by the hand, and going a little farther with them under the trees, made them a very urgent proposal. At first they rejected it, but she obliged them to comply by her threats. Having obtained what she desired, she perceived that each of them had a ring on his finger, which she demanded. As soon as she had received them, she pulled out a string of other rings, which she shewed the princes, and asked them if they knew what those jewels meant? “No,” said they, “we hope you will be pleased to inform us.” “These are,” she replied, “the rings of all the men to whom I have granted my favours. There are fourscore and eighteen, which I keep as memorials of them; and I asked for yours to make up the hundred. So that I have had a hundred gallants already, notwithstanding the vigilance of this wicked genie, who never leaves me. He may lock me up in this glass box and hide me in the bottom of the sea; but I find methods to elude his vigilance. You may see by this, that when a woman has formed a project, there is no husband or lover that can prevent her from putting it in execution. Men had better not put their wives under such restraint, as it only serves to teach them cunning.” Having spoken thus to them, she put their rings on the same string with the rest, and sitting down by the monster, as before, laid his head again upon her lap, end made a sign to the princes to depart.

They returned immediately the way they had come, and when they were out of sight of the lady and the genie Shier-ear said to Shaw-zummaun “Well, brother, what do you think of this adventure? Has not the genie a very faithful mistress? And do you not agree that there is no wickedness equal to that of women?” “Yes, brother,” answered the king of Great Tartary; “and you must also agree that the monster is more unfortunate, and more to be pitied than ourselves. Therefore, since we have found what we sought for, let us return to our dominions, and let not this hinder us from marrying. For my part, I know a method by which to preserve the fidelity of my wife inviolable. I will say no more at present, but you will hear of it in a little time, and I am sure you will follow my example.” The sultan agreed with his brother; and continuing their journey, they arrived in the camp the third night after their departure.

The news of the sultan’s return being spread, the courtiers came betimes in the morning before his pavilion to wait his pleasure. He ordered them to enter, received them with a more pleasant air than he had formerly done, and gave each of them a present. After which, he told them he would go no farther, ordered them to take horse, and returned with expedition to his palace.

As soon as he arrived, he proceeded to the sultaness’s apartment, commanded her to be bound before him, and delivered her to his grand vizier, with an order to strangle her, which was accordingly executed by that minister, without inquiring into her crime. The enraged prince did not stop here, but cut off the heads of all the sultaness’s ladies with his own hand. After this rigorous punishment, being persuaded that no woman was chaste, he resolved, in order to prevent the disloyalty of such as he should afterwards marry, to wed one every night, and have her strangled next morning. Having imposed this cruel law upon himself, he swore that he would put it in force immediately after the departure of the king of Tartary, who shortly took leave of him, and being laden with magnificent presents, set forward on his journey.

Shaw-zummaun having departed, Shier-ear ordered his grand vizier to bring him the daughter of one of his generals. The vizier obeyed. The sultan lay with her, and putting her next morning into his hands again in order to have her strangled, commanded him to provide him another the next night. Whatever reluctance the vizier might feel to put such orders in execution, as he owed blind obedience to the sultan his master, he was forced to submit. He brought him then the daughter of a subaltern, whom he also put to death the next day. After her he brought a citizen’s daughter; and, in a word, there was every day a maid married, and a wife murdered.

The rumour of this unparalleled barbarity occasioned a general consternation in the city, where there was nothing but crying and lamentation. Here, a father in tears, and inconsolable for the loss of his daughter; and there, tender mothers dreating lest their daughters should share the same fate, filling the air with cries of distress and apprehension. So that, instead of the commendation and blessings which the sultan had hitherto received from his subjects, their mouths were now filled with imprecations.

The grand vizier who, as has been already observed, was the unwilling executioner of this horrid course of injustice, had two daughters, the elder called Scheherazade, and the younger Dinarzade. The latter was highly accomplished; but the former possessed courage, wit, and penetration, infinitely above her sex. She had read much, and had so admirable a memory, that she never forgot any thing she had read. She had successfully applied herself to philosophy, medicine, history, and the liberal arts; and her poetry excelled the compositions of the best writers of her time. Besides this, she was a perfect beauty, and all her accomplishments were crowned by solid virtue.

The vizier loved this daughter, so worthy of his affection. One day, as they were conversing together, she said to him, “Father, I have one favour to beg of you, and most humbly pray you to grant it.” “I will not refuse,” answered he, “provided it be just and reasonable.” “For the justice of it,” resumed she, “there can be no question, and you may judge of this by the motive which obliges me to make the request. I wish to stop that barbarity which the sultan exercises upon the families of this city. I would dispel those painful apprehensions which so many mothers feel of losing their daughters in such a fatal manner.” “Your design, daughter,” replied the vizier “is very commendable; but the evil you would remedy seems to me incurable. How do you propose to effect your purpose?” “Father,” said Scheherazade, “since by your means the sultan makes every day a new marriage, I conjure you, by the tender affection you bear me, to procure me the honour of his bed.” The vizier could not hear this without horror. “O heaven!” he replied in a passion, “have you lost your senses, daughter, that you make such a dangerous request? You know the sultan has sworn, that he will never lie above one night with the same woman, and to command her to be killed the next morning; would you then have me propose you to him? Consider well to what your indiscreet zeal will expose you.” “Yes, dear father,” replied the virtuous daughter, “I know the risk I run; but that does not alarm me. If I perish, my death will be glorious; and if I succeed, I shall do my country an important service.” “No, no,” said the vizier “whatever you may offer to induce me to let you throw yourself into such imminent danger, do not imagine that I will ever consent. When the sultan shall command me to strike my poniard into your heart, alas! I must obey; and what an employment will that be for a father! Ah! if you do not dread death, at least cherish some fears of afflicting me with the mortal grief of imbuing my hands in your blood.” “Once more father,” replied Scheherazade, “grant me the favour I solicit.” “Your stubbornness,” resumed the vizier “will rouse my anger; why will you run headlong to your ruin? They who do not foresee the end of a dangerous enterprise can never conduct it to a happy issue. I am afraid the same thing will happen to you as befell the ass, which was well off, but could not remain so.” “What misfortune befell the ass?” demanded Scheherazade. “I will tell you,” replied the vizier, “if you will hear me.”

The Ass, the Ox, and the Labourer.

A very wealthy merchant possessed several country-houses, where he kept a large number of cattle of every kind. He retired with his wife and family to one of these estates, in order to improve it under his own direction. He had the gift of understanding the language of beasts, but with this condition, that he should not, on pain of death, interpret it to any one else. And this hindered him from communicating to others what he learned by means of this faculty.

He kept in the same stall an ox and an ass. One day as he sat near them, and was amusing himself in looking at his children who were playing about him, he heard the ox say to the ass, “Sprightly, O! how happy do I think you, when I consider the ease you enjoy, and the little labour that is required of you. You are carefully rubbed down and washed, you have well-dressed corn, and fresh clean water. Your greatest business is to carry the merchant, our master, when he has any little journey to make, and were it not for that you would be perfectly idle. I am treated in a very different manner, and my condition is as deplorable as yours is fortunate. Daylight no sooner appears than I am fastened to a plough, and made to work till night, which so fatigues me, that sometimes my strength entirely fails. Besides, the labourer, who is always behind me, beats me continually. By drawing the plough, my tail is all flayed; and in short, after having laboured from morning to night, when I am brought in they give me nothing to eat but sorry dry beans, not so much as cleansed from dirt, or other food equally bad; and to heighten my misery, when I have filled my belly with such ordinary stuff, I am forced to lie all night in my own dung: so that you see I have reason to envy your lot.”

The ass did not interrupt the ox; but when he had concluded, answered, “They that called you a foolish beast did not lie. You are too simple; you suffer them to conduct you whither they please, and shew no manner of resolution. In the mean time, what advantage do you reap from all the indignities you suffer. You kill yourself for the ease, pleasure, and profit of those who give you no thanks for your service. But they would not treat you so, if you had as much courage as strength. When they come to fasten you to the stall, why do you not resist? why do you not gore them with your horns, and shew that you are angry, by striking your foot against the ground? And, in short, why do not you frighten them by bellowing aloud? Nature has furnished you with means to command respect; but you do not use them. They bring you sorry beans and bad straw; eat none of them, only smell and then leave them. If you follow my advice, you will soon experience a change, for which you will thank me.”

The ox took the ass’s advice in very good part, and owned he was much obliged to him. “Dear Sprightly,” added he, “I will not fail to do as you direct, and you shall see how I will acquit myself.” Here ended their conversation, of which the merchant lost not a word.

Early the next morning the labourer went for the ox. He fastened him to the plough and conducted him to his usual work. The ox, who had not forgotten the ass’s counsel, was very troublesome and untowardly all that day, and in the evening, when the labourer brought him back to the stall, and began to fasten him, the malicious beast instead of presenting his head willingly as he used to do, was restive, and drew back bellowing; and then made at the labourer, as if he would have gored him with his horns. In a word, he did all that the ass had advised him. The day following, the labourer came as usual, to take the ox to his labour; but finding the stall full of beans, the straw that he had put in the night before not touched, and the ox lying on the ground with his legs stretched out, and panting in a strange manner, he believed him to be unwell, pitied him, and thinking that it was not proper to take him to work, went immediately and acquainted his master with his condition. The merchant perceiving that the ox had followed all the mischievous advice of the ass, determined to punish the latter, and accordingly ordered the labourer to go and put him in the ox’s place, and to be sure to work him hard. The labourer did as he was desired. The ass was forced to draw the plough all that day, which fatigued him so much the more, as he was not accustomed to that kind of labour; besides he had been so soundly beaten, that he could scarcely stand when he came back.

Meanwhile, the ox was mightily pleased; he ate up all that was in his stall, and rested himself the whole day. He rejoiced that he had followed the ass’s advice, blessed him a thousand times for the kindness he had done him, and did not fail to express his obligations when the ass had returned. The ass made no reply, so vexed was he at the ill treatment he had received; but he said within himself, “It is by my own imprudence I have brought this misfortune upon myself. I lived happily, every thing smiled upon me; I had all that I could wish; it is my own fault that I am brought to this miserable condition; and if I cannot contrive some way to get out of it, I am certainly undone.” As he spoke, his strength was so much exhausted that he fell down in his stall, as if he had been half dead.

Here the grand vizier, himself to Scheherazade, and said, “Daughter, you act just like this ass; you will expose yourself to destruction by your erroneous policy. Take my advice, remain quiet, and do not seek to hasten your death.” “Father,” replied Scheherazade, “the example you have set before me will not induce me to change my resolution. I will never cease importuning you until you present me to the sultan as his bride.” The vizier, perceiving that she persisted in her demand, replied, “Alas! then, since you will continue obstinate, I shall be obliged to treat you in the same manner as the merchant whom I before referred to treated his wife a short time after.”

The merchant understanding that the ass was in a lamentable condition, was desirous of knowing what passed between him and the ox, therefore after supper he went out by moonlight, and sat down by them, his wife bearing him company. After his arrival, he heard the ass say to the ox “Comrade, tell me, I pray you, what you intend to do to-morrow, when the labourer brings you meat?” “What will I do?” replied the ox, “I will continue to act as you taught me. I will draw back from him and threaten him with my horns, as I did yesterday: I will feign myself ill, and at the point of death.” “Beware of that,” replied the ass, “it will ruin you; for as I came home this evening, I heard the merchant, our master, say something that makes me tremble for you.” “Alas! what did you hear?” demanded the ox; “as you love me, withhold nothing from me, my dear Sprightly.” “Our master,” replied the ass, “addressed himself thus to the labourer: Since the ox does not eat, and is not able to work, I would have him killed to-morrow, and we will give his flesh as an alms to the poor for God’s sake, as for the skin, that will be of use to us, and I would have you give it the currier to dress; therefore be sure to send for the butcher.’ This is what I had to tell you,” said the ass. “The interest I feel in your preservation, and my friendship for you, obliged me to make it known to you, and to give you new advice. As soon as they bring you your bran and straw, rise up and eat heartily. Our master will by this think that you are recovered, and no doubt will recall his orders for killing you; but, if you act otherwise, you will certainly be slaughtered.”

This discourse had the effect which the ass designed. The ox was greatly alarmed, and bellowed for fear. The merchant, who heard the conversation very attentively, fell into a loud fit of laughter. His wife was greatly surprised, and asked, “Pray, husband, tell me what you laugh at so heartily, that I may laugh with you.” “Wife,” replied he, “you must content yourself with hearing me laugh.” “No,” returned she, “I will know the reason.” “I cannot afford you that satisfaction,” he, “and can only inform you that I laugh at what our ass just now said to the ox. The rest is a secret, which I am not allowed to reveal.” “What,” demanded she “hinders you from revealing the secret?” “If I tell it you,” replied he, “I shall forfeit my life.” “You only jeer me,” cried his wife, “what you would have me believe cannot be true. If you do not directly satisfy me as to what you laugh at, and tell me what the ox and the ass said to one another, I swear by heaven that you and I shall never bed together again.”

Having spoken thus, she went into the house, and seating herself in a corner, cried there all night. Her husband lay alone, and finding next morning that she continued in the same humour, told her, she was very foolish to afflict herself in that manner; that the thing was not worth so much; that it concerned her very little to know while it was of the utmost consequence to him to keep the secret: “therefore,” continued he, “I conjure you to think no more of it.” “I shall still think so much of it,” replied she, “as never to forbear weeping till you have satisfied my curiosity.” “But I tell you very seriously,” answered he, “that it will cost me my life if I yield to your indiscreet solicitations.” “Let what will happen,” said she, “I do insist upon it.” “I perceive,” resumed the merchant, “that it is impossible to bring you to reason, and since I foresee that you will occasion your own death by your obstinacy, I will call in your children, that they may see you before you die.” Accordingly he called for them, and sent for her father and mother, and other relations. When they were come and had heard the reason of their being summoned, they did all they could to convince her that she was in the wrong, but to no purpose: she told them she would rather die than yield that point to her husband. Her father and mother spoke to her by herself, and told her that what she desired to know was of no importance to her; but they could produce no effect upon her, either by their authority or intreaties. When her children saw that nothing would prevail to draw her out of that sullen temper, they wept bitterly. The merchant himself was half frantic, and almost ready to risk his own life to save that of his wife, whom he sincerely loved.

The merchant had fifty hens and one cock, with a dog that gave good heed to all that passed. While the merchant was considering what he had best do, he saw his dog run towards the cock as he was treading a hen, and heard him say to him: “Cock, I am sure heaven will not let you live long; are you not ashamed to ad thus to-day?” The cock standing up on tiptoe, answered fiercely: “And why not to-day as well as other days?” “If you do not know,” replied the dog, “then I will tell you, that this day our master is in great perplexity. His wife would have him reveal a secret which is of such a nature, that the disclosure would cost him his life. Things are come to that pass, that it is to be feared he will scarcely have resolution enough to resist his wife’s obstinacy; for he loves her, and is affected by the tears she continually sheds. We are all alarmed at his situation, while you only insult our melancholy, and have the impudence to divert yourself with your hens.”