9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

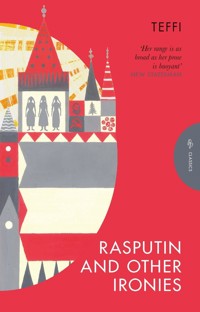

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Masterful stories of faith and superstition from a much-loved Russian author, in English for the first time 'A magnificent edition of the works of a writer who deserves her seat at the top table of Russian authors' Sara Wheeler, Wall Street Journal These stories conjure a vanished Russia, where Orthodox Christianity coexists with the shapeshifters and house spirits of ancient folk belief. Celebrated for her sublime wit and graceful style, Teffi here plumbs the darker aspects of psychology, infusing tales of domestic conflict with the occult spirituality that thrived in the country of her youth. A young girl, haunted by the sinister sound of a church bell, resolves to become first a brigand, then a saint. A reluctant participant in a pilgrimage to the Solovetsky Islands has a shatteringly profound experience. A recently married couple's relationship becomes strained as they each silently nurse the fear that their maid is a witch. By turns playful and profound, solemn and drily sceptical, these tales of other worlds precisely illuminate human desires, fears and failings.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

i

“Teffi is one of the great writers of early 20th century Russia, from Nicholas II’s reign to the Revolution afterwards. Her writing, whether stories or reportage or memoir is witty, elegant, fantastical, yet sharp and acute and playful”

Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of The Romanovs

“[Teffi’s work is] amazingly modern, as easy to devour as, well, a box of chocolates”

Observer

“Pushkin Press deserves our thanks for bringing Teffi to a much wider audience”

Spectator

“The translucent surface of her writing gives sight of the depths of the human spirit: its raging and yearning, its dark nights and joyous awakenings, its wild cries, its anarchic craziness”

New York Review of Books

“One of the great twentieth-century writers. At their best her short stories are to my mind the equal of Chekhov’s”

John Gray

“Conceived as a gathering of Teffi’s stories featuring witches, shape-shifters, mermaids, vampires… the book stands as a masterwork of high non-reductive psychological realism worthy of Henry James”

LA Review of Books

3

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

There are writers who muddy their own water, to make it seem deeper. Teffi could not be more different: the water is entirely transparent, yet the bottom is barely visible.

—Georgy Adamovich1

It is not unusual for a writer to be pigeonholed, but few great writers have suffered from this more than Teffi. Several of her finest works are extremely bleak, but many Russians still know only the comic and satirical sketches she wrote during her first years as a professional writer, from 1901 until 1918. Few critics have recognized the full breadth of her human sympathy, her Chekhovian ability to write convincingly about people from every level of society: illiterate peasants, respectable bourgeois, monks and priests, eccentric poets, bewildered émigrés, and public figures ranging from Lev Tolstoy to Rasputin and Lenin. Teffi also has a remarkable gift for writing about children, for showing us the world from the perspective of a small child.

Throughout her life, Teffi was a practicing member of the Russian Orthodox Church. Both Orthodox Christianity and Russian folk religion, with its often poetic understanding of spiritual matters, were important to her. And she recognized that many of her finest stories were those inspired by these themes. In December 1943, she wrote to the historian Piotr Kovalevsky: “Which of my things do I most value? I think that the stories ‘Solovki’ and ‘A Quiet Backwater’ and the collection Witch are well written. In Witch you find our ancient Slav gods, how they still live on in the soul of the people, in legends, viiisuperstitions, and customs. Everything as I encountered it in the Russian provinces, as a child.”2

Teffi made few such direct statements about her work. I know just one other passage in a similar vein:

During those years of my distant childhood, we used to spend the summer in a wonderful, blessed country—at my mother’s estate in Volhynia Province. I was very little. I had only just begun to learn to read and write—so I must have been about five. […] What slipped quickly through the lives of adults was for us a matter of complex and turbulent experience, entering our games and our dreams, inserting itself like a brightly colored thread into the pattern of our life, into that first firm foundation that psychoanalysts now investigate with such art and diligence, seeing it as the prime cause of many of the madnesses of the human soul.3

These two statements have guided our choice of stories. We have translated all but one of the stories from Witch.4 We have included the two other stories Teffi mentions: “Solovki,” an account of a pilgrimage to the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea, and “A Quiet Backwater,” which incorporates a memorable monologue about the patron saints of various birds, insects, and animals. And we have chosen ten other stories on similar themes, many of them from the first of Teffi’s more serious collections, The Lifeless Beast. For the main part, we present the stories according to their order of publication. The one exception is that we begin with “Kishmish,” which was written much later. This short, semiautobiographical story serves as a perfect introduction to many of the main themes of Other Worlds.

This is the first time that Teffi’s more “otherworldly” stories have been brought together in this manner. Our hope is that this will allow readers a clearer sense of the depth of understanding beneath her often dazzling wit and brilliance.

ixTeffi was well aware of how often her work was misunderstood. Her preface to The Lifeless Beast begins:

I do not like prefaces. […]

I would not be writing a preface now were it not for a sad incident.

In October 1914 I published the story “Yavdokha.” This melancholy and painful story is about a lonely old peasant woman. She is illiterate and muddle-headed and so hopelessly benighted that, when she receives news of the death of her son, she is unable to grasp what has happened. Instead, she wonders whether or not he will be sending her money.

One angry newspaper then […] indignantly scolded me for laughing at human grief.

“What does Madame Teffi find funny about this?” the newspaper asked indignantly. After quoting the very saddest passages of all, it repeated, “And does she consider this funny? And is this funny, too?”

The newspaper would probably be most surprised if I were to tell it that I did not laugh for a single minute. […]

And so the aim of this preface is to warn the reader that there is a great deal in this book that is not funny.5

Several of the stories in The Lifeless Beast seem startlingly modern. The journalist’s misunderstanding shows us how far beyond the conventions of her time Teffi had moved. Yavdokha has no companion but a hog and is hunchbacked from living in a hut that has sunk deep into the ground. She lives five miles from the nearest village and is alienated both from the other peasants and from everything to do with the Russian state. After someone has read out a letter informing her of her son’s death she repeats the word “war”—but it is unclear if she even grasps what the word means and she certainly does not take in that her son has died. Yavdokha could have stepped out of one of Samuel Beckett’s last plays.x

Curiously, misunderstandings not unlike the journalist’s are a central theme of The Lifeless Beast. In some stories, the misunderstandings arise from differences of social class; in others, it is the young and healthy who fail to understand the old and needy; in still others it is adults who fail—or do not even try—to understand children. Teffi’s portrayal of human failings is unflinching; in “Happiness,” she describes happiness as an “empty and hungry” creature that can survive only if fed with the “warm, human meat” of someone else’s envy. In a smaller number of stories, however, she evokes moments of genuine love and compassion. In “Daisy,” a seemingly inane aristocratic lady enrolls as a military nurse because that is the fashionable thing to do, quickly becomes involved in her work, and, to her surprise, is deeply moved by the gratitude of an uneducated soldier she helps to treat.6 “The Heart” follows a similar pattern; Rakhatova, a frivolous actress, thinks it would be entertaining to confess to a simple, poorly educated monk before receiving Communion in a remote monastery. She is taken aback by the monk’s spontaneous joy when she says she has not “committed any grave sins.”

The eyes now looking at her were so clear and joyful that they seemed to be flickering, just as stars flicker when their clear light overflows. […]

“Praise the Lord! Praise the Lord!”

He was trembling all over. It was as if he were a large severed heart and a drop of living water had fallen onto it. The heart quivers—and then all the other dead, severed pieces quiver too.

As always, Teffi’s imagery is carefully developed. The last sentence refers back to the scene that greeted Rakhatova and her friends when they arrived at the monastery the previous day:

The peasant was hacking at the fish with a broad knife. […]

Then the peasant took a bucket and poured water over the pieces of fish and the severed head. There was a sudden movement xiin one of the middle pieces. A twitch, a quiver—and the whole fish responded. Even the chopped-off tail jerked.

“That’s its heart contracting,” said the Medico.

Born in 1872, Teffi was a contemporary of Alexander Blok and other leading Russian Symbolists. Her own poetry is derivative, but in her prose she shows a remarkable gift for grounding Symbolist themes and imagery in the everyday world. “The Heart” is entirely realistic and at times even gossipy—yet the story is permeated throughout with Christian symbolism relating to fish. In “A Quiet Backwater,” she achieves a still more successful synthesis of the heavenly and the earthly. Toward the end of this seven-page story a laundress gives a long disquisition on the name days of various birds, insects, and animals. The mare, the bee, the glowworm—she tells a young visitor—all have their name days. And so does the earth herself: “And the Feast of the Holy Ghost is the name day of the earth herself. On this day, no one dairnst disturb the earth. No diggin, or sowin—not even flower pickin, or owt. No buryin t’ dead. Great sin it is, to upset the earth on ’er name day. Aye, even beasts understand. On that day, they dairnst lay a claw, nor a hoof, nor a paw on the earth. Great sin, yer see.” In a key poem—almost a manifesto—of French Symbolism, Charles Baudelaire interprets the whole world as a web of mystical “correspondences.” In a less grandiose way, Teffi conveys a similar vision. She was, I imagine, delighted by the paradox of the earth’s name day being the Feast of the Holy Spirit—not, as one might expect, the feast of a saint associated with some activity like plowing.

The Lifeless Beast is notable for its striking imagery and bold rendition of peasant speech, and for being one of a very few treatments in Russian literature of the First World War as experienced by civilians. Teffi’s insight into human selfishness and viciousness never wavers. Nevertheless, she remains true to her faith in Christian love—as practiced by Daisy in a field hospital, as experienced by Rakhatova through Orthodox ritual, and as embodied in the generous, restorative understandings of folk religion.xii

In early 1920 Teffi settled in Paris. Russian émigrés throughout the world were quick to set up publishing houses and Teffi was one of their most valued authors. In 1921 alone she published five books: two miniature selections of articles and stories, in Berlin; a collection of comic sketches, in Shanghai; the short-story collection Black Iris, in Stockholm; and A Quiet Backwater—which includes most of the stories from The Lifeless Beast—in Paris.

Teffi’s high standing is still more clearly shown by her publications in periodicals. “Ke fer?” (Que Faire?)—a brilliant evocation of the Russians’ sense of alienation in Paris—was published in April 1920, in the first issue of the important The Latest News. And “Solovki”—an almost Bruegelesque account of the widespread practice of mass pilgrimage to holy sites—was the first item in the first issue (August 1921) of the glamorous, lavishly illustrated journal The Firebird, which featured work by almost all the best-known émigré writers and artists. These two publications serve as markers to the twin paths Teffi would follow for the next fifty years. Many of her stories are about the mishaps and absurdities of émigré life; others are about a long-lost past.

“Solovki” was republished in Evening Day. Teffi’s following collection, A Small Town (Paris, 1927), is not represented in Other Worlds, since most of the stories deal with her émigré present—the “small town” of Russian Paris—rather than her Russian past. We have, however, included three stories from The Book of June. Like “Solovki,” the title story is a sympathetic account of overwhelming religious experience. Here, however, Teffi enters more deeply into the heroine’s inner world, into her most inarticulate thoughts and feelings; it is one of Teffi’s most sensitive treatments of adolescence.

Most of the stories in Witch bear the titles of folkloric beings—for example, “Wonder Worker,” “The House Spirit,” or “Rusalka” (a female water spirit resembling the Lorelei). Some of the stories are xiiigrim, some fanciful, some sober and philosophical. Some are realistic, with only the merest hint at the supernatural; in others, the supernatural motifs are more pronounced. Sometimes a character tries all too transparently to cover up his or her misconduct through some implausible supernatural explanation; sometimes it is the rationalist skeptics who appear foolish and blinkered. One piece, “About the House,” is hardly a story at all—more like a chatty retelling of a scholarly article, with a brief anecdote tacked on at the end.

All the stories are presented from the perspective of a Russian exile. Often the tone is nostalgic. Sometimes there is a note of bewilderment: Could such things truly have happened? Could such a world as old Russia really have existed?

Witch is a coherent and self-contained collection. Its main themes, however, are anticipated in “Wild Evening” and “Shapeshifter,” the last two stories in The Book of June. The central character of these two stories—and also of the first and last stories of Witch—is clearly modeled on Teffi herself. In 1892, aged twenty, Teffi married a lawyer by the name of Vladislav Buchinsky. We know little about her years as a young wife and mother, living in small provincial towns, but we know from statements Teffi made later that she was deeply unhappy.

“Wild Evening” is about fear of the unknown; except for an opportunistic peddler, everyone in the story—the young Teffi, the monks, even the horse—is in a state of terror. All around lurk threatening forces—darkness, cattle plague, the unclean dead. “Shapeshifter” may represent Teffi’s fantasy of a different course her life might have followed; a stranger’s chance intervention prompts the Teffi figure to decide against marriage to a lawyer who has much in common with the real-life Buchinsky. The opening, title story of Witch shows us a young husband and wife feeling more and more exasperated with each other as they grow ever more afraid—though neither will admit it—of a maid suspected of witchcraft. And in “Wolf Night,” the concluding story of Witch, we glimpse this same husband and wife perhaps a year or two later. The husband has grown even more resentful and evil-tempered, and the wife—now pregnant—is overwhelmed by nightmares of the house being surrounded by wolves. Ten lines xivbefore the end of the story, the husband says to the wife, “Please! Do me a favor! Go and stay with your oh so clever mother. A fine way she must have brought you up, to make you into such a hysteric.”

Teffi did not ever go back to her “oh so clever mother,” though it is possible that her husband may have uttered some sarcasm similar to the above. All we know for sure is that in 1898, probably on the edge of a breakdown, Teffi abandoned her husband and three children and moved back to Petersburg to begin her career as a professional writer. There is little doubt that this rupture—which she very seldom spoke about—was a source of almost unbearable guilt and pain. Nevertheless, the words she wrote nearly fifty years later to her eldest daughter have the ring of truth. After saying she had been a bad mother, Teffi backtracks: “In essence I was good, but circumstances drove me from home, where, had I remained, I would have perished.”7

At the heart of Witch, framed by these stories drawing on her unhappy life as a young woman, stands a group of six stories in which Teffi moves further back in time, to her own childhood. At one level, these can be read as a fictional treatment of folk beliefs in Volhynia (now part of western Ukraine). At the same time, they constitute a memorial to Teffi’s younger sister Lena, the closest to her of her six siblings. Lena had died in 1919, and Teffi writes movingly about her death in Memories, which she completed only shortly before the stories in Witch. In both books, Teffi portrays herself and Lena as inseparable.

One of these stories, “The Kind That Walk,” is a study of antisemitism—and of xenophobia more generally. Teffi deftly shows us people’s blind fear of Moshka, an honest and competent Jewish carpenter; she is equally deft in evoking the fascination with which she and Lena listen to the adults’ wild talk about how Moshka, many years earlier, had been dragged off by the devil. Many of the other main characters in these six stories are domestic servants. Teffi’s mother and some of her elder siblings appear now and then, but it is the children’s Nyanya, or nanny, who is the most important authority figure.

There are also two stories set mainly in Moscow and Petersburg. xvThe longer of these, “The Dog,” begins with the narrator, Lyalya, recalling idyllically happy summers as a teenager on a country estate in the company of friends and admirers. In those days, she says with pained emphasis, she was carefree and high-spirited. She had felt briefly troubled, however, by the intense feeling with which a shy young boy called Tolya once swore eternal devotion to her, promising always to remain her “faithful dog.” A few years later, Lyalya falls in with the bohemian crowd who frequent the Stray Dog, the famous Petersburg cabaret where all the major poets of the time used to give readings. Somehow, almost inadvertently, Lyalya takes up with Harry Edvers, a particularly odious pseudo-poet who later ends up working for the Cheka, the Bolshevik security police. In the story’s final scene she calls on her “faithful dog” for help—with dramatic results. Lyalya concludes,

That’s the whole story; that’s what I wanted to tell you. I’ve made nothing up; I’ve added nothing; and there’s nothing I can explain—or even want to explain. But when I turn back and consider the past, I can see everything clearly. I can see each separate event and the axis or thread upon which a certain force had strung them.

It had strung the events on the thread like beads and tied up the loose ends.

“The Dog” is convincing on every level. As an evocation of a lost childhood paradise, the first pages bear comparison with the work of Teffi’s friend and colleague Ivan Bunin. As a reckoning with the febrile cultural world of prerevolutionary Petersburg, it anticipates Anna Akhmatova’s Poem Without a Hero (written 1940–1965). Like Akhmatova, Teffi sees the bohemian abandonment of traditional moral values as having paved the way for the brutalities and duplicities of Communism. And the denouement provides a fine example of a writer drawing on the occult not for exotic ornament but as a source of psychological truth. The huge dog’s sudden appearance may be mere chance; it may be a real embodiment of Tolya’s loyal and xviresolute spirit; or it may be Tolya’s spirit prompting Lyalya toward an act that requires superhuman powers. Teffi has taken care not to exclude any of these possibilities. Unlike the “certain force” spoken of by her narrator, she does not tie up the story’s loose ends.

In the letter quoted earlier, Teffi says of Witch, “This book has been highly praised by Bunin, Kuprin, and Merezhkovsky. They praised it for its artistry and the excellence of its language. I am, by the way, proud of my language, which critics have seldom commented on.”8

Teffi’s pride is justified. Along with Andrey Bely, Ivan Bunin, Vladimir Nabokov, and Andrey Platonov, she is one of a number of great twentieth-century Russian prose writers who were also poets but whose poetic gifts found their truest expression in prose. It is difficult, though, to define what makes Teffi’s language so remarkable. She makes skillful use of repetition, often using a single word as a leitmotif for an entire story. In “Wild Evening,” for example, she uses the adjective “dikii” (wild) of a horse’s eye, of the night, of a person, and of the dangerously high seat of a two-wheel carriage. In “Rusalka” she repeats “mutnyi” (murky, cloudy, troubled) more and more often in the course of the story; she uses the word especially often in relation to the two sisters’ troubled visions in the last pages, when one of the housemaids either drowns or turns into a rusalka and the girls fall ill with scarlet fever. It is also true that Teffi has a fine ear for the linguistic peculiarities of people from different social groups—ranging from Volhynia peasants to Russian émigrés in Paris; it is not for nothing that the satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko, as a novice writer, noted down some of Teffi’s most striking coinages and malapropisms.9 Nevertheless, the 1920s was a rich period for Russian prose and none of the above is enough to make Teffi unique.

What truly sets her apart is her lightness of touch. More than Vladislav Khodasevich, more than Akhmatova or any of the Acmeist poets, it is Teffi who has inherited the grace and fluency of Pushkin. She can write as simply and tautly as Hemingway—but without the least sense of willed tightness. She can write long, complex sentences xviidense with embedded participial clauses, yet these sentences, unlike apparently similar sentences in the work of Bunin, retain a conversational quality. Some of her more unreliable narrators come out with phrases as memorably absurd as characters out of Zoshchenko—yet even here there is a difference. Zoshchenko’s sentences seem brilliantly constructed; Teffi’s appear simply to have happened. It may be for this very reason—her success in creating an illusion of naturalness—that Teffi’s language has received so little scholarly attention.

Many of her greatest contemporaries, however, were well aware of her gifts. Zoshchenko studied her intently; Bunin admired her; Mikhail Bulgakov borrowed from her Civil War articles for his The White Guard. And Georgy Ivanov referred to Teffi as “a unique phenomenon in Russian literature, a true miracle that people will still be wondering at in a hundred years’ time, crying and laughing at once.”10

The last two pieces in this collection are “Baba Yaga” and “Volya,” two essays from Earthly Rainbow (published six months before Teffi’s death), in which Teffi asserts her profound Russianness. Baba Yaga is the name of the archetypal Russian folktale witch and the word “volya” is used for what Teffi understands as a peculiarly Russian kind of unbounded emotional freedom. Both essays end with a heartfelt cry. Baba Yaga, confined in her wintry hut, longing for wildness, freedom, and open spaces, cries, “B—o—r—i—n—g.” And in the last lines of “Volya” the aging Teffi remembers herself as a young woman, waving at the spring dawn and crying out, “Vo-o-o-ly-a-a-a!” Shortly before this, she has heard a boy on the other side of the river singing his heart out. The last line of his song—“Sing Volya, Volya,Volya!”—is described as “heartrending, piercingly joyful, like a sudden yelp, coming from somewhere too deep in the soul.”

Teffi is indeed one of the most graceful of Russian writers. It seems likely, however, that this grace is a way of managing an almost unbearable burden of pain. There are a great many heartfelt cries in these stories. Some of these cries and desperate screams seem almost infectious, so agonizing that those who hear them can’t help but let out xviiisimilar screams. The epileptic sleigh driver in “Shapeshifter,” for example, lets out a cry with “something so terrible about it” that the narrator screams too, jumping up from her seat and almost tumbling out of the sleigh. And the narrator of “Witch” describes, at some length, the scream of a guinea hen “wailing for her slaughtered mate.” She continues,

This isn’t easy to explain to you, but such a cry of inconsolable despair, above the dead little town, in the silence of that trackless steppe, was more than any human soul could bear.

I remember coming home and saying to my husband, “Now I know why people hang themselves.”

He screamed, clutching his head in his hands.

In the last pages of “The Book of June,” Katya lets out repeated screams of terror: “Katya had no idea what made her keep on screaming like this. Some kind of lump seemed to be filling her throat, making her gasp and wheeze and scream out Grisha’s name.” And two of Teffi’s very finest works end with still wilder cries. The heroine of “Solovki” gives herself up to a prolonged scream during a service in the main monastery church: “What mattered was not to stop, to expend more and more of herself in the cry, to give herself to it more intensely, yes, more and more of herself: Oh, if only they didn’t get in her way. Oh, if only they let her keep going… But it was so hard. Would she have the strength?”

One of the most painful passages in all Teffi’s work is the last page of her autobiographical Memories, her account of her final, irrevocable departure from Russia. It is the summer of 1919 and she is on her way to Istanbul, on a boat leaving Novorossiysk harbor:

From the lower deck comes the sound of long, obstinate wails, interspersed with words of lament.

Where have I heard such wails before? Yes. I remember. During the first year of the war. A gray-haired old woman was being taken down the street in a horse-drawn cab. Her hat had xixslipped back onto the nape of her neck. Her yellow cheeks were thin and drawn. Her toothless black mouth was hanging open, crying out in a long tearless wail: “A-a-a-a-a!” Probably embarrassed by the disgraceful behavior of his passenger, the driver was urging his poor horse forward, whipping her on.

Yes, my good man, you didn’t think enough about whom you were picking up in your cab. And now you’re stuck with this old woman. A terrible, black, tearless wail. A last wail. Over all of Russia, the whole of Russia …No stopping now…

These cries and wails differ in tone. The boy’s “sudden yelp” in “Volya” is “piercingly joyful,” whereas the gray-haired woman in Memories is mired in despair. In at least one respect, however, the cries are all too similar. All are painfully raw; all come from “somewhere too deep in the soul.” It is as if these characters have been flayed. Layers of protective skin have been torn away and what should be hidden lies dangerously exposed.

Teffi’s grace seems all the more precious when we understand that it was both a protective cloak and her way of trying to keep her footing. It may perhaps have been what enabled her, unlike many of her contemporaries, to preserve her balance and sanity throughout a seemingly never-ending series of catastrophes—the First World War, the Russian Civil War, the viciousness of émigré political infighting, and life under German occupation during the Second World War. If Teffi liked to refer to herself as a witch, if she identified at the end of her life with Baba Yaga, this may be because she was hoping to charm the inner and outer darkness, to cast a spell on it that might keep it at bay.

—Robert Chandler

NOTES

1 Georgy Adamovich, review of The Book of June, Illiustrirovannaya Rossiya (April 25, 1931).

2 Teffi, Izbrannye proizvedeniya (Moscow: Lakom, 1999), 2:9. Edythe C. Haber quotes a similar passage in Teffi: A Life of Letters and of Laughter (London: I. B. Tauris, 2019), 152.

3 Teffi, “Katerina Petrovna,” ibid., 4:45.

4 For more about Witch, including a discussion of “Seemings,” which is set in a Siberian mining settlement and is omitted from Other Worlds, see Robert Chandler in The Literary Encyclopedia, available at www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=38906.

5 Teffi, Izbrannye proizvedeniya, 2:374.

6 Neither “Happiness” nor “Daisy” are included in Other Worlds. For more about The Lifeless Beast, see Robert Chandler in The Literary Encyclopedia, available at www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=38906.

7 Haber, Teffi: A Life of Letters and of Laughter, 18.

8 Ibid., 152.

9 Edythe C. Haber, “The Roots of NEP Satire: The Case of Teffi and Zoshchenko,” in The NEP Era: Soviet Russia 1921–1928 (Idyllwild, CA: Charles Schlacks, 2007), 1:92.

10 Ivanov’s comments about Teffi are often misquoted. See, for example, Teffi, Izbrannye proizvedeniya, 2:5. Haber writes (personal email, June 25, 2020) that she found in her files a note of Ivanov’s review in Sovetskii patriot of Russkii sbornik (1946) where he writes, “The first Teffi is a cultured, intelligent, good writer. The second is an unrepeatable phenomenon of Russian literature, a true miracle that people will still be wondering at in a hundred years’ time, crying and laughing at once. (‘Pervaya Teffi kul'turnyi, umnyi, khoroshii pisatel'. Vtoraya—nepovtorimoye yavlenie 271russkoi literaturi, podlinnoye chudo, kotoroy cherez sto let budut udivlyat'sya, smeyas' pri etom do slez.’)” It is not entirely clear which Teffi is the first, and which the second. It seems likely, though, that the first is the more serious Teffi and the second the more comic Teffi.

xx

PART ONE

from Earthly Rainbow (1952)

2

KISHMISH

Lent. Moscow.

In the distance, the muffled sound—between a hum and a boom—of a church bell. The clapper’s even strokes merge into a single, oppressive moan.

An open door, into murky predawn gloom, allows a glimpse of a dim shape, rustling stealthily about the room. Now it stands out, a dense patch of gray; now it dissolves, merging into the surrounding dark. The rustling quietens. The creak of a floorboard—and of a second floorboard, farther away. Silence. Nyanya has left—on her way to the early-morning service.1

She is observing Lent.2

Now things get frightening.

Barely breathing, the little girl lying in bed curls into a small ball. She listens and watches, listens and watches.

The distant hum is becoming sinister. The little girl is all alone and defenseless. If she calls, no one will come. But what can happen? Night must be ending now. Probably the cocks have greeted the dawn and the ghosts are all back where they belong.

And they belong in cemeteries, in bogs, in lonely graves under simple crosses, or by forsaken crossroads on the outskirts of forests. Not one of them will dare touch a human being now; the Liturgy is being celebrated and prayers are being said for all Orthodox Christians. What is there to be frightened of?

But an eight-year-old soul does not believe the arguments of reason. 4It shrinks into itself, quietly trembling and whimpering. An eight-year-old soul does not believe that this is the sound of a bell. Later, in daytime, it will believe this, but now, alone, defenseless, and in anguish, it does not know that this is a bell calling people to church. Who knows what this sound might be? It is sinister. If anguish and fear could be translated into sound, this is the sound they would make. If anguish and fear could be translated into color, it would be this uncertain, murky gray.

And the impression made by this predawn anguish will remain with this little creature for many years, for her whole life. This creature will continue to be woken at dawn by a fear and anguish beyond understanding. Doctors will prescribe sedatives; they will advise her to take evening walks, or to give up smoking, or to sleep in an unheated room, or with the window open, or with a hot water bottle on her liver. They will counsel many, many things—but nothing will erase from her soul the imprint of that predawn despair.

The little girl’s nickname was “Kishmish”—a word for a kind of very small raisin from the Caucasus. This was, no doubt, because she was so very small, with a small nose and small hands. Small fry, of little importance. Toward the age of thirteen she would suddenly shoot up. Her legs would grow long and everyone would forget that she had ever been a kishmish.3

But while she still was a little kishmish, this hurtful nickname caused her a great deal of pain. She was proud and she longed to distinguish herself in some way; she wanted, above all, to do something grand and unusual. To become, say, a famous strongman, someone who could bend horseshoes with their bare hands or stop a runaway troika in its tracks. She liked the idea of becoming a brigand or—still better—an executioner. An executioner is more powerful than a brigand since it is he who has the last word. And could any of the grown-ups have imagined, as they looked at this skinny little girl with shorn flaxen hair, quietly threading beads to make a ring—could any of them have imagined what terrible dreams of power were seething 5inside her head? There was, by the way, yet another dream—of becoming a dreadful monster. Not just any old monster, but the kind of monster that really frightens people. Kishmish would stand by the mirror, cross her eyes, pull the corners of her mouth apart, and thrust her tongue out to one side. But first she would say in a deep voice, acting the part of an unknown gentleman standing behind her, unable to see her face and addressing the back of her head, “Do me the honor, madame, of this quadrille.”

She would then put on her special face, spin around on her heels, and reply, “Very well—but first you must kiss my twisted cheek.”

The gentleman would run away in horror. “Hah!” she would call after him. “Scared, are you?”

Kishmish had begun her studies. To start with—Scripture and Handwriting.

Every task one undertook, she learned, should be prefaced with a prayer.

This was an idea she liked. But since she was still, among other things, considering the career of brigand, it also caused her alarm.

“What about brigands?” she asked. “Must they say a prayer before they go out briganding?”

No one gave her a clear answer. All people said was “Don’t be silly.” And Kishmish did not understand. Did this mean that brigands don’t need to pray—or that it is essential for them to pray, and that this is so obvious that it was silly even to ask about it?

When Kishmish grew a little bigger and was preparing to make her first confession, she underwent a spiritual crisis. Gone now were the terrible dreams of power.

“Lord, Hear Our Prayer” was, that year, being sung very beautifully.

Three young boys would step forward, stand beside the altar, and sing in angelic voices. Listening to them, a soul grew humble and tender. These blessed sounds made a soul wish to be light, white, ethereal, and transparent, to fly away in sounds and incense, right up to the cupola, to where the white dove of the Holy Spirit had spread its wings.

This was no place for a brigand. Nor was it the right place for an 6executioner, or even a strongman. As for the monster, it would stand outside the door and cover its terrible face. A church was certainly no place to be frightening people. Oh, if only she could get to be a saint. How marvelous that would be! So beautiful, so fine and sweet. To be a saint was above everything and everyone. More important than any teacher, headmistress, or even provincial governor.

But how could she become a saint? She would have to work miracles—and Kishmish had not the slightest idea how to go about this. Still, miracles were not where you started. First, you had to lead a saintly life. You had to make yourself meek and kind, to give everything to the poor, to devote yourself to fasting and abstinence.

So how would she give everything to the poor? She had a new spring coat. That was what she should give away first.

But how furious Mama would be. There would be a most unholy row, the kind of row that didn’t bear thinking about. And Mama would be upset, and saints were not supposed to hurt other people and make them upset. What if she gave her coat to a poor person but told Mama it had simply been stolen? But saints were not supposed to tell lies. What a predicament. Life was a lot easier for a brigand. A brigand could lie all he wanted—and just laugh his sly laugh. How, then, did these saints ever get to be saints? Simply, it seemed, because they were old—none of them under sixteen, and many of them real oldies. No question of any of them having to obey Mama. They could give away all their worldly goods just like that. No, this clearly wasn’t the place to start—it was something to keep till the end. She should start with meekness and obedience. And abstinence. She should eat only black bread and salt, and drink only water straight from the tap. But here too lay trouble. Cook would tell on her. She would tell Mama that Kishmish had been drinking water that hadn’t been boiled. There was typhus in the city and Mama did not allow her to drink water from the tap. But then, once Mama understood that Kishmish was a saint, perhaps she would stop putting obstacles in her path.

And then, how marvelous to be a saint. There were so few of them these days. Everyone she knew would be astonished.

“Why’s there a halo over Kishmish?” 7

“What, didn’t you know? She’s been a saint for some time now.”

“Heavens! I don’t believe it!”

“There she is. See for yourself!”

And she would smile meekly as she went on eating her black bread and salt.

Her mother’s visitors would feel envious. Not one of them had saintly children.

“Are you sure she’s not just pretending?”

Fools! Couldn’t they see her halo?

She wondered how soon the halo would begin. Probably in a few months. It would be fully present by autumn. God, how marvelous all this was. Next year she’d go along to confession. The priest would say in a severe voice, “What sins have you committed? You must repent.”

And she would reply, “None at all. I’m a saint.”

“No, no!” he would exclaim. “Surely not!”

“Ask Mama. Ask her friends. Everyone knows.”

The priest would question her. Maybe there had, after all, been some tiny little sin?

“No, none at all!” she would repeat. “Search all you like!”

She also wondered if she would still have to do her homework. If so, this too might prove awkward. Because saints can’t be lazy. And they can’t be disobedient. If she were told to study, then she’d have to do as they said. If only she could learn miracles straightaway! One miracle—and her teacher would take fright, fall to her knees, and never mention homework again.

Next she imagined her face. She went up to the mirror, sucked in her cheeks, flared her nostrils, and rolled her eyes heavenward. Kishmish really liked the look of this face. A true saint’s face. A little nauseating, but entirely saintly. No one else had a face anything like it. And so—off to the kitchen for some black bread!

As always before breakfast, Cook was cross and preoccupied. Kishmish’s visit was an unwelcome surprise. “And what’s a young lady like you doing here in the kitchen? There’ll be words from your mama!” 8

There was an enticing smell of Lenten fare: fish, onions, and mushrooms. Kishmish’s nostrils twitched involuntarily. She wanted to retort, “That’s none of your business!,” but she remembered that she was a saint and said in a quiet voice, “Varvara, please cut me a morsel of black bread.” She thought for a moment, then added, “A large morsel.”

Cook cut her some bread.

“And will you sprinkle a little salt on it,” she continued, looking up as if to the heavens.

She would have to eat the bread then and there. If she went anywhere else with it, there would be misunderstandings. With unpleasant consequences.

The bread was particularly tasty and Kishmish regretted having only asked for one slice. Then she filled a jug from the tap and drank some water. Just then the maid came in.

“I’ll be telling your mama,” she exclaimed in horror, “that you’ve been drinking tap water!”

“She’s just eaten a great chunk of bread,” said Cook. “Bread and salt. So what do you expect? She’s a growing girl.”

The family was called in to breakfast. Kishmish couldn’t not go. So she decided to go but not eat anything. She would be very meek.

For breakfast there was fish soup and pies. She sat there, looking blankly at the little pie on her plate.

“Why aren’t you eating?”

In answer she smiled meekly and once more put on her saintly face—the face she had been practicing before the mirror.

“Heavens, what’s gotten into her?” exclaimed her astonished aunt. “Why’s she pulling such a dreadful face?”

“And she’s just eaten a great big chunk of black bread,” said the telltale maid. “Just before breakfast—and she washed it down with water straight from the tap.”

“Whoever said you could go and eat bread in the kitchen?” shouted Mama. “And why were you drinking tap water?”

Kishmish rolled her eyes and flared her nostrils, once and for all perfecting her saintly face. 9

“What’s gotten into her?”

“She’s making fun of me!” squealed the aunt—and let out a sob.

“Out you go, you vile little girl!” Mama exclaimed furiously. “Off to the nursery with you—and you can stay there on your own for the rest of the day!”

“And the sooner she’s packed off to boarding school, the better,” said the aunt, still sobbing. “My nerves, my poor nerves. Literally, my every last nerve …”

Poor Kishmish.

And so she remained a sinner.

Translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler

NOTES

1Nyanya is often translated as “nanny,” but the two words are not equivalent. See “A Note on Russian Names.”

2 The Russian Orthodox refer to the first week of Lent as Clean Week. The faithful are expected to undergo spiritual cleansing through fasting, prayer, repentance, begging forgiveness of their neighbor, and taking the Eucharist. Throughout the six weeks of Lent, vegetable oils are substituted for butter and animal fats.

3 Teffi also uses this nickname in “Love” (“Lyubov,” from the collection Gorodok), one of the finest of her semiaubiographical stories. Robert Chandler’s translation of this is included in Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida (New York: Penguin Classics, 2005).

PART TWO

from The Lifeless Beast (1916)

12

SOUL IN BOND

At the Dvuchasovs’ country house, their old Nyanya was readying herself for death; she had been doing this for ten years.

In summertime, a small kitchen was put at her disposal. It was a little timber-board room next to the dairy where they made curd cheese. In winter, with the master’s family gone to the city, she would move herself to the corridor in the main building. There, in a corner behind a dresser, she would sit or lie on her trunk and carry on with her dying until spring.

Come spring, she’d pick a dry, sunny day, stretch a rope between a pair of trees out in the birch grove, and air her burial clothes: a long yellowed linen shirt, a pair of embroidered slippers, a pale blue belt—embroidered with a prayer for the repose of the dead—and a small cypress-wood cross.

For her this was the most interesting day of the year. She’d wave a stick around, trying to keep the gnats off her burial clothes, and talk to herself about different cemeteries—which were dry and which damp—and about what kind of shoes it’s best to put on the dead, so they won’t make the floorboards creak at night.

“Nah then, Nyanya,” a servant might chuckle. “Mekk sure ye mind that shirt, eh? Not gooin to last thi much longer than twenty year, is it? Tha’d ’ave to mekk thisself a new ’un, wouldn’t ye?”

Come winter, though, she’d be left all on her own in the empty echoing house. All day she’d sit in her corner behind the dresser. In the evenings she’d drag herself to the kitchen to drink tea with the caretaker woman. 14

Nyanya comes and sits herself down. And starts talking. A long rambling story, and she seems to have left out the beginning. At first, the caretaker tries to make sense of it all, but after a while she gives up.

“… An’ she come to the old biddy’s daughter-in-law…” Nyanya mumbles on, pursing her lips to stop a nub of sugar falling from her mouth.1 “She come an’ says, ‘I want to mekk misself some spiced bread—’ere, Matriona, gi’ us some cardamom, would ye?’ Nah, why would I ’ave any cardamom, eh? So I tells ’er, you leave ol’ Matriona alone nah, there’s a good lass. Stop mitherin, and go and pester summn else. Aye, that shut ’er up, good n’ proper.”

“Oh Nyanya, who’re you goin’ on about nah?” says the caretaker. But Nyanya doesn’t hear.

“And what’s to fret about, anyway? I’ve lit me lamps, stood up to pray, and bent to each corner. ‘Nah then, old soul stealer,’ I says to ’im, ‘Can ye hear me dahn there? You leave me in peace while I’m prayin. After that, do as you will, for thine is the power an’ the glory, as they say.’ An’ I know he can’t touch me.”

“Oh, my days!” says the startled caretaker. “Him dahn there an’ the power and the glory—the words ye come out with …”