Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

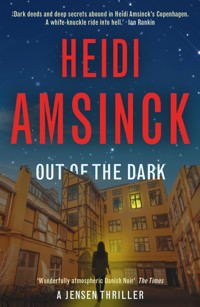

'Dark deeds and deep secrets abound in Heidi Amsinck's Copenhagen. A white knuckle ride into hell.' IAN RANKIN. 'Amsinck's Copenhagen-set crime series is reliably excellent.' MAIL ON SUNDAY. 'Relentless tension pulses through every page of this meticulously plotted thriller.' THOMAS ENGER. 'Nordic noir at its finest…outstanding…This is superior crime fiction.' JOAN SMITH, SUNDAY TIMES, PICK OF THE MONTH. 'The author's finest work.' SUN, PICK OF THE WEEK. A missing child ... a tainted witness ... Jensen's darkest case yet. Matilde Clausen, 9, vanishes from a crowded playground in the middle of Copenhagen, triggering a frantic search across the city. When a possible link emerges to the disappearance of Lea Høgh, 10, six years ago, DI Henrik Jungersen is thrown back into the nightmare that almost finished his career. Desperate for redemption, but barred from reopening the old case, Henrik turns to his estranged lover, Dagbladet chief crime reporter Jensen, for help.As the investigation reaches deep into Denmark's underworld, how will Henrik, Jensen, and her troubled teenage apprentice Gustav escape the darkness that threatens to engulf them, in time to solve the mystery? What really happened to Lea? And where on earth is Matilde?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 416

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

OUT OF THE DARK

By the same author

Last Train to Helsingør

My Name is Jensen

The Girl in the Photo

Back From the Dead

First published by Muswell Press in 2025

Copyright © Heidi Amsinck 2025 by agreement with Grand Agency

Typeset in Bembo by M Rules

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781068684418

eISBN: 9781068684425

Heidi Amsinck has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is a work of fiction, and except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may not be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form, or by any means without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Muswell Press, London N6 5HQ

www.muswell-press.co.uk

Our authorised representative in the EU for product safety is Easy Access System Europe, Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

To Nick

December

Day One

1

Detective Inspector Henrik Jungersen counted to three, flung open his car door and sprinted for the wrought-iron gates at the entrance to Ørstedsparken.

At least the rain kept the ghouls away, he thought as he nodded at the unlucky cop on guard duty and slipped inside the park.

The TV news crews were staying in their vans, watching from behind steamed-up windows.

Good.

He had no answers anyway.

One question had been gnawing at his brain all morning: how was it possible to abduct a child in the middle of Copenhagen, barely a couple of hundred yards from a busy metro station, shops and fast-food restaurants, without anyone noticing?

Nine-year-old Matilde Clausen had been missing for seventeen hours.

The playground, dug into the slope between the street and the large, vaguely boomerang-shaped lake in the middle of the park, was now a crime scene. As Henrik descended into the sandy hollow surrounded by trees and shrubbery, Detective Sergeant Mark Søndergreen came rushing towards him with an umbrella.

His face mirrored Henrik’s strong sense that something was horribly wrong.

Every parent’s worst nightmare.

‘They haven’t found anything, Boss,’ said Mark, gesturing at the technicians working in among the trees.

Henrik wasn’t surprised. Trampled on by dozens of kids and parents and soaked in overnight rain, the ground was unlikely to yield anything useful. But they had to try. ‘At this stage, nothing is irrelevant,’ he had told his team of investigators at the morning briefing.

The mobile phone Matilde had been given for her ninth birthday despite her mother’s protests was switched off, last detected inside the park a few minutes after she went missing. If they found it, they might be able to determine if she had been in touch with anyone of potential interest.

‘Give me a moment,’ said Henrik as he sheltered under Mark’s umbrella with the rain hammering on the canopy.

His jeans and boots were soaked, and water was trickling inside the collar of his shirt and down his back. He welcomed the icy sensation; he needed to stay awake, alert.

The past few months were a blur, a blank nothingness of training, shifts and paperwork.

Little daylight penetrated the thick cloud. The opposite end of Ørstedsparken, a sunken oasis of tranquillity close to Nørreport Station, was lost in the misty gloom.

You could almost feel it, the northern hemisphere hurtling towards the point furthest from the sun. The Christmas lights that had sprung up all over the city made a flimsy defence against the enveloping darkness.

Henrik tried to imagine what the playground would have been like yesterday afternoon, with screaming children crawling on the timber frame and being pushed on the swings by adults chatting and warming their hands on takeaway coffees.

It had been brighter then, a brief respite from the perpetual winter rain, but bitterly cold. The park would have looked beautiful, the light from the setting sun glinting off the surface of the lake, the old roofs and spires of the city just visible beyond the tree-lined perimeter.

‘Talk to me,’ he said finally, turning to Mark who had been waiting patiently, knowing better than to interrupt his boss when he was getting his bearings.

Good old Mark. Younger and fitter than him, energetic, loyal and hardworking. Did as he was told, a forgotten virtue in society at large, Henrik had always felt.

Mark had been a godsend after the turbulent events of the summer, quietly holding him up whenever he felt his knees buckling under him.

Above all, Mark knew when to keep his mouth shut and when to speak.

‘Stine Clausen . . . she’s the mother . . . was sitting over there, with Matilde’s half-brother asleep in the pram,’ said Mark.

He pointed to a wooden picnic table decorated with graffiti and Henrik was reminded that Ørstedsparken was open twenty-four hours. It was also widely known in Copenhagen as a gay cruising spot. Had been for more than 150 years. In his time, Henrik had dealt with rapes here, and a few stabbings, but never a missing child. Usually, such cases were solved before they reached his desk.

‘And where was Matilde?’ he said.

‘In there apparently.’ Mark gestured at the area of trees and bushes close to the picnic table, a mixture of evergreens and naked branches with a few yellow leaves clinging on for dear life.

Henrik had read in the notes that Matilde was a shy child, slight for her age. He frowned. ‘What was she doing in there?’

Mark shrugged.

‘And Stine?’ said Henrik.

‘On her phone, apparently. She would check now and again for Matilde, looking for her red coat, but then the baby began to cry, and she got busy settling him. When she looked up again, she couldn’t see her daughter.’

For how long had she been preoccupied? Henrik wondered. Phones made people deaf and blind; they got sucked in, forgot their surroundings.

(‘You should know,’ said his wife in his head.)

He kept meaning to put his phone away, to stop scrolling, but it had been like a compulsion in him lately, a shield against his thoughts and, God forbid, having to talk.

There had been other people in the park yesterday, lots of potential witnesses, and no one had reported seeing a little girl dragged off against her will. Someone Matilde knew then?

The distance from the playground to the nearest road made it hard to see how it could have been an opportunist move. It must have been planned meticulously, rehearsed even.

He rubbed his hand over the rough skin of his scalp and face. ‘And then what?’

‘Stine wasn’t too worried at first,’ said Mark. ‘Only when Matilde didn’t respond to her calls did she begin to panic. Other parents joined the search. They ran all over the park, and after about fifteen minutes, Stine called the police. It was almost completely dark by then.’

Henrik didn’t have to imagine that part. He could feel the primal fear of it, hear the increasingly desperate cries for Matilde echoing between the trees, the scene transformed from serenity to terror in a heartbeat.

‘The first uniforms were here in eight minutes and more arrived after that,’ Mark said. ‘They sealed off the playground and closed the park. The rest you know.’

Yeah, thought Henrik. The rest is a big fat zero.

The overnight response by operational command at Bellahøj police station had been textbook; he couldn’t fault it. The trouble was that none of it had worked.

Henrik looked at the lake, wondering if they would have to get the divers out.

Mark read his mind. ‘Matilde had been told not to go near the water under any circumstances.’

Since when did kids do as they’re told? Henrik thought.

But he didn’t truly believe the girl had drowned in the lake. It was more likely that she had left by the nearest exit to the playground, on the corner of Ahlefeldtsgade and Nørre Farimagsgade.

Alone or with someone.

Voluntarily or by force.

Most of the people who had been in the park when Matilde disappeared would have left by the time the police arrived. They needed those potential witnesses to come forward.

He looked at his phone, seeing missed calls from several crime reporters.

Jensen was a crime reporter, and knew his number, but she hadn’t called.

For months now, they had managed to avoid each other.

In the summer, when Jensen’s attempt to build a life with a new boyfriend had ended in disaster, he had been glad, hoping things could now go back to normal between them.

Until she had told him that she was pregnant and keeping the baby.

Jensen as a mother? It was unthinkable.

And it had changed everything.

Dreaming that he and Jensen might one day be together had made his marriage tolerable, like the possibility of escape, however remote, keeping a prisoner from abandoning all hope.

Now, the dream was dead. There would always be a child between him and Jensen.

Another man’s child.

The child of a psychopath.

He hadn’t known what else to do but throw himself into work – the more work the better.

He sighed, considering whether to return the reporters’ calls. The media would spread the word faster, encouraging witnesses to come forward, and he needed that, but was loath to get drawn into speculation about what might or might not have happened.

Seeing everyone in one go would save time.

And Jensen might come.

Her baby was due soon, but if he knew her at all, she would be working until she went into labour, possibly beyond it. The thought made him smile, despite himself.

‘Get the press department to call a doorstep,’ he said to Mark. ‘As soon as possible.’

Mark shuffled his feet, too polite to remind Henrik that his boss, Superintendent Jens Wiese, was wary of him addressing the press.

Wiese was wary of him full stop.

If it were up to Wiese, he would only see daylight, muzzled and on a tight leash, when strictly necessary.

‘You weren’t my first choice,’ Wiese had said that morning when he had assigned Henrik as lead investigator on the Matilde case.

Wiese needed good statistics but held his nose when it came to the grime and chaos of real-life police work.

Henrik knew it wasn’t always pretty.

‘I need this one handled sensitively,’ Wiese had said. ‘A missing child this close to Christmas is bound to cause a lot of fear. Her parents are beside themselves with worry. I don’t want you crashing about in your size tens causing chaos.’

Henrik had blinked at him innocently. ‘Why do you assume I’m going to?’

‘I’ve been watching you, Jungersen,’ Wiese replied. ‘You’re stressed, erratic, on edge. When did you last take leave?’

‘I don’t remember,’ he said. ‘But as you pointed out yourself, we’re busy, so what are you going to do, send me home?’

Wiese had scowled at him, but Henrik knew he had no choice. There were just three lead investigators in Copenhagen’s violent crime unit, and Jonas and Lotte, his peers, were both up to their necks in cases.

He turned to Mark. ‘Just do it. I can handle the media.’

Just as well Jensen wasn’t here to hear him say that. He could see her face now, hands on hips, dark-blue eyes flashing at him angrily.

Those eyes.

Stop it, Jungersen.

He shook his head again, and began to walk towards the nearest exit, with Mark hot on his heels.

‘Get back to work, everyone,’ he shouted gruffly. ‘Let’s find Matilde.’

2

The chatter around Dagbladet’s meeting table died instantly when Margrethe stepped through the door, tall and broad, dressed in a navy-blue blazer with a silver brooch.

For all the joy she spread in the room, she might as well have worn a black cloak and carried a scythe.

Someone had brought in an advent candle stuck in clay and decorated with fir branches and spray-on snow. The work of a nursery child, Jensen guessed.

It seemed inappropriate now, a pathetic gesture in the face of Dagbladet’s existential crisis.

After its takeover by a Swedish venture capital fund, the paper had seemed to turn a corner, but the positive momentum hadn’t lasted. Rumours had been circulating for weeks that the Swedes had lost patience and were looking for further cut-backs.

The production of the print edition had already been outsourced to an agency, only a few subs remained, and repeated rounds of redundancies had reduced the editorial staff to a skeleton crew.

The pressure told on the faces of the journalists assembled around the beaten-up boardroom table. What was going to happen next? For how much longer could they carry on?

‘We’re going all out on the Matilde Clausen story,’ said Margrethe, her figure casting a shadow across the print copies scattered in front of her.

Jensen’s article about the missing nine-year-old had made it onto the front page minutes before deadline last night but in the bottom corner, below a story about flooding caused by weeks of heavy rain.

By now, Matilde was the only story. Her smiling face, adult front teeth just poking through the gums, stared out from every digital front page in the land. She looked younger than her years, her white-blonde hair scraped back with a plastic tiara.

‘What do we know?’ said Margrethe.

Jensen felt her colleagues turn to stare at her. Her hair was still wet after the bike ride from Margrethe’s flat in Østerbro, her sweatshirt soaked through where her coat would no longer do up.

‘Very little,’ she said. ‘The police have just called a press conference.’

‘Does that mean they’ve found her?’ said Margrethe.

‘More likely the opposite,’ said Jensen. ‘They’ll be appealing to the public for help.’

‘So, what’s the plan?’ said Margrethe.

‘Find out if they have any theories about what happened, try to speak to Matilde’s family, her school, neighbours, friends,’ said Jensen.

All of it seemed inadequate.

‘I want regular updates throughout the day. Give it everything you’ve got,’ said Margrethe.

Jensen nodded, refreshing the feed on her phone for the hundredth time.

Still no news.

The baby kicked, startling her. She looked at her bump, watching as it shifted and moved under her jumper. It still felt unreal, like her body belonged to someone else.

She had been seven weeks gone by the time she found out she was pregnant. Not too late to have an abortion, as the doctor had pointed out when Jensen had told her that the father was no longer around.

The fact that he was a murderer awaiting trial was something she had kept to herself.

She hadn’t so much decided to keep the baby, as drifted past the twelve-week point of no return without deciding. How could she, knowing that it might be her only chance to have a child?

Margrethe had taken her in when she had lost her home back in the summer. It was supposed to have been for a few weeks, but Jensen hadn’t managed to find a flat within a reasonable cycling distance of the newspaper. At least, not one she could afford on her single income.

No matter which way she looked at it, her situation was dire. No home of her own, no partner, and a baby arriving in a couple of months.

Her year in Copenhagen was starting to look like a failed experiment.

She could go back to London, lose herself in the anonymity of a city with almost twice the population of Denmark. The container with her belongings was already there; she had returned it just a few months after first arriving in Copenhagen, convinced she wouldn’t be staying. It had felt right to keep things temporary, to be able to leave quickly if a time came when it all got too much.

Such as now.

She spent the rest of the editorial meeting scrolling through the Danish news sites, quickly concluding that no one had any more information than she did on Matilde Clausen’s disappearance.

The TV news channels were all showing the same looped footage of officers moving in the rain behind the taped-off entry to Ørstedsparken.

When Margrethe slammed shut the black spiral notebook in which she orchestrated the news of the day, people quickly scrambled to their feet, relieved to have made it through another meeting without some grim announcement.

Margrethe cleared her throat loudly. ‘Wait,’ she shouted. ‘There’s more.’

The room fell silent, a collective suspension of breath. Outside, across the square with the giant Christmas tree, the bells in the City Hall tower began to strike the hour.

‘As you know,’ Margrethe began, ‘we’ve cut our overheads significantly in the past year, but I’m afraid we must tighten our belts further.’

Were more people about to be sacked? Or would the rumours that the Swedes were dropping Dagbladet’s print edition finally turn out to be true?

‘Hear me out,’ Margrethe said, raising her voice above the anxious mumbling. ‘As there are fewer of us now, we must shrink our footprint. Come the New Year, we’ll be renting out the top floor of this building.’

A sigh of relief went round the table; everyone had imagined something far worse.

Everyone but Jensen.

She stared at Margrethe in disbelief. Her private room in the warren of corridors under the eaves where journalists had once been milling in and out of each other’s smoke-filled offices to the tap-tap sound of typewriters had been her sanctuary, a safe space where she could ease her way into newspaper life after years of solitude as a foreign correspondent.

‘To whom?’ she said.

‘A technology start-up. I forget the name,’ said Margrethe, with a dismissive wave.

That figured. Dagbladet was yielding ground, literally, to the digital juggernaut that was threatening to obliterate it.

Margrethe pushed out her chin. ‘The few of you still up there will need to be out by Christmas for the refurbishment to start.’

‘But what about Henning?’ said Jensen, clutching at straws. ‘What’s he going to say when he comes back and finds some baby-faced coder in his office?’ The former editor who had come out of retirement to become Dagbladet’s obituary writer was still off work after a stroke in the summer. His office was across the hall from Jensen’s.

‘Henning won’t be coming back,’ said Margrethe. ‘As you’d know if you’d seen him lately.’

Jensen bit her lip. She had visited the old man a few times in the concrete towers at Riget, the national hospital in the middle of the city, but not for a while now. She had assumed that he was recovering, that she would hear his slow, shuffling footsteps in the corridor any day now.

‘We’re also going to be doubling down on our digital strategy,’ said Margrethe. ‘We’ll be stepping up video production, in addition to our podcasting. I’d like you to meet Jannik Fogh, who’s joining us today in a new role of video editor,’ said Margrethe with a sweeping motion of her left hand.

A muscular, red-bearded man in his thirties, wearing a black Copenhell festival T-shirt and combat trousers, stood up from where he had been resting on a windowsill, behind a pillar, and took a bow. Jensen hadn’t noticed him before.

‘We’re going after a younger readership, and Jannik will be working closely with our social media team to make sure we reach them,’ said Margrethe.

People around the table were nodding and smiling, and Jannik was beaming at them in return.

Jensen was frozen to her chair. Until a few months ago, Margrethe’s teenage nephew, Gustav, had been creating Dagbladet’s videos, working as Jensen’s unpaid journalist trainee after getting expelled from school.

She had been reluctant at first, but they had made a good team, notching up a handful of scoops between them.

The office had fallen quiet after he had returned to high school. She missed him terribly: his big mouth, his crazy ideas, even his incessant vaping.

‘Oh, and Jensen,’ said Margrethe as she gathered her papers, notebook and phone and rose to her feet, ‘Jannik will be joining you in covering the Matilde case.’

Across the room, where he was busy shaking the hands of his new colleagues who had got out of their seats to welcome him, Jannik met Jensen’s eye and winked.

3

The door to the second-floor flat in Kleinsgade was ajar. Low voices came from inside, mixed with the kind of anguished sobbing that Henrik had heard too many times in his life.

Mark knocked politely on the door. ‘Hello?’ he said.

Henrik pushed past him, following the voices as he picked his way through the jumble of boots and bags in the hallway, sidestepping the pram that took up most of the space.

The living room fell quiet when he entered, everyone looking up at him anxiously. He raised his hands, wanting to get the disappointment out of the way quickly. ‘We don’t have Matilde yet, I’m afraid.’

There was an audible exhalation.

The room was dominated by a giant TV, the sleek modern interior fighting a losing battle with baby paraphernalia and a set of hefty dumbbells in the corner.

In the centre of the sofa, a slight woman with thickly drawn eyebrows and dark hair tied into a ponytail was slumped over, crying miserably. She was clutching a soft toy, a blue rabbit. By her side, holding her hand, sat who Henrik assumed to be the owner of the weight-lifting equipment: a tall, red-faced, muscular man with crew-cut blond hair and a stubbly beard. Both his arms were covered in Viking tattoos.

An older woman, the grandmother perhaps, stood by the window trying to settle a whimpering baby. She was surrounded by a handful of people: friends, neighbours or perhaps relatives, all with worried expressions on their faces.

Henrik addressed himself to the couple on the sofa. ‘You must be Stine and Simon,’ he said, holding up his warrant card. ‘I’m Detective Inspector Jungersen from Copenhagen Police, and I believe you’ve already met Detective Sergeant Mark Søndergreen.’

The moment passed when they might have shaken hands.

He gestured at the group on the other side of the room. ‘Could we talk in private for a while?’

The visitors shuffled out, the baby screeching as it reached for Stine. She turned her face away. ‘I can’t,’ she sobbed, leaning into her husband’s chest.

‘I want you to know that we’re doing everything we can to find Matilde,’ said Henrik.

‘Oh yeah? What are you doing here then?’ said Simon, flashing him an angry look.

‘We’ve a big team working on this case with no let-up, I promise you,’ said Henrik, pointing to an armchair. ‘May I?’ He sat down without waiting for an answer, keeping to the edge to prevent his wet jeans from staining the seat. ‘I know this is difficult. I’ll try to be as quick as I can. While we talk, do you think Mark here could have a look in your daughter’s room?’

‘What for?’ said Simon, scowling.

His wife was holding onto his jumper, white-knuckled, as though fearful of slipping onto the floor. Her whole body was trembling as she cried.

‘It’s routine. We’re looking for clues, any clues, as to what might have happened,’ said Henrik, nodding at Mark, who quickly made himself scarce.

‘Stine,’ Henrik began. ‘I need you to think for me. You told us you got to the playground around a quarter to three in the afternoon yesterday. On your way there, did Matilde say anything to you?’

‘No,’ she sobbed. ‘I was exhausted, so I wanted to stay at home, but she persuaded me to go. She was skipping along the pavement.’

‘Did she say why she was so keen?’

‘She loves it there.’

Henrik passed her a tissue. ‘What did you talk about on the way?’

‘I don’t remember,’ she said, blowing her nose.

‘That’s all right. And what about earlier in the day?’

‘She played in her room, I made her pasta for lunch and then we walked to the park, like always.’

‘Always?’ said Henrik.

‘Every Sunday, unless it’s raining, or I’ve been up all night with Daniel.’

That made sense, Henrik thought. Plenty of time for someone to watch and plan, picking off the little girl who preferred to play by herself, befriending her, ensuring that she would come away freely.

‘We shouldn’t have gone,’ Stine cried. ‘If only we’d stayed at home, Matilde would be here now.’

‘Don’t torture yourself,’ Henrik said. He gave her a moment. ‘I understand that she was playing alone in the shrubbery. Why was that?’

‘It’s quiet in there. She finds the other kids too noisy and boisterous.’

‘So, it’s a regular thing?’

‘Pretty much.’

‘And you were on your phone when it happened?’

‘Yes.’

‘Talking to someone?’

‘No, just scrolling.’

The answers were robotic, toneless. Simon, on the other hand, seemed to be getting more and more agitated, his nostrils flaring as he breathed.

Henrik ignored him. ‘Have you ever seen Matilde talk to anyone?’

‘Sometimes we meet one of her friends from school.’

‘I mean an adult, a stranger.’

‘No,’ Stine said, raising her voice. ‘I’d never let her do that.’

‘I understand,’ said Henrik. ‘What about having a feeling that you were being watched while in the park? Or recognising people from previous visits?’

‘I don’t . . .’ Stine turned to Simon, uncertain. ‘What is he saying?’

‘Look,’ Simon said, his face the colour of a ripe tomato. ‘She’s told you nothing happened. She didn’t see anyone, and she and Matilde didn’t talk about anything.’

‘No arguments? No telling off?’ said Henrik, keeping his gaze on Stine.

‘What difference does that make?’ Simon snapped.

Stine lifted her tearstained face and looked at Henrik.

‘Do you have kids?’

‘Three,’ he said, trying to convey with his eyes that he understood her pain.

All of it.

Simon got up. ‘I’ve had enough of this,’ he said. ‘Our friends are out there looking right now, same as you ought to be.’

Henrik took a deep breath. He couldn’t blame the man for kicking off, would probably have done the same in his place. Still, Simon was starting to get on his nerves. ‘Last night was confusing,’ he said to Stine. ‘You might have forgotten something that will turn out to be important. People out of place. Unusual sounds. A conflict with Matilde earlier in the day, even if it felt insignificant at the time.’

Simon frowned. ‘Matilde wouldn’t have run off because she’d had an argument with Stine. It would be completely out of character.’

‘We’re keeping an open mind, not ruling anything in or out,’ said Henrik, looking at him. ‘Tell me, where were you yesterday afternoon?’

Predictably, Simon’s face went from red to almost purple. ‘What the hell has that got to do with anything?’

‘Just tell them,’ Stine said.

‘I was at the gym,’ said Simon. ‘Satisfied?’

‘We’ll need the details,’ said Henrik. ‘To verify the information.’

‘You don’t have a clue, do you?’ Simon spat. ‘That’s why you’re sitting here worrying about where I was yesterday, instead of doing your job. If you’re so determined to speak to someone, why don’t you talk to Stine’s ex?’

Stine pulled at his sleeve. ‘No, Simon, don’t start. You promised me.’

He jerked his arm away. ‘They need to know what the creep is like. If you won’t tell them, then I will.’

‘Do you mean Matilde’s biological father?’ said Henrik, leaning forward. According to the officers who had spoken to him last night, Rasmus Nordby had been upset at the news that his estranged daughter was missing. ‘Why do you say that?’

‘Ask at Matilde’s school. They’ll tell you.’

‘Simon, no,’ said Stine.

Again, he ignored her, freeing himself of her imploring hand. Henrik’s dislike of the man grew.

‘He was caught looking through the fence at the little kiddies, wasn’t he?’ said Simon. ‘One of the other parents complained.’

‘When was this?’ said Henrik, leaning forward.

‘More than six months ago. He just wanted to see Matilde,’ said Stine.

Simon looked at her. ‘He had his phone out to take pictures.’

‘Were the police called?’ said Henrik.

‘Yes, but of course you guys let him go with a slap on the wrist.’

‘He hadn’t done anything,’ said Stine.

‘He’s a paedophile,’ said Simon.

‘He wouldn’t harm his own daughter,’ said Stine. She turned to Henrik. ‘Simon and I got full custody of Matilde in the spring. The thing at the school happened just after that. There’s been no repeat.’

‘So, Rasmus never sees Matilde?’

Stine shook her head. ‘Not anymore.’

Henrik nodded and got up, his knees creaking. ‘OK,’ he said. ‘We’ll check it out.’

Big tears rolled down Stine’s cheeks as she looked up at him, seized with fear and desperation. ‘Someone’s taken her, haven’t they?’

Henrik believed in being straight with people. He tried desperately to think of something truthful that would reassure the woman but drew a blank. ‘We have to face that possibility, yes,’ he said.

Stine screamed like a wounded animal, a thin, heartrending sound.

‘Have you slept?’ he said. ‘If you’re struggling, your doctor may be able to give you something to help.’

She made a strangled sound, as her hand flew to her mouth. ‘I’m going to be sick,’ she said, rushing for the door.

Simon followed her out.

Henrik found Mark in Matilde’s bedroom. He was shaking his head. ‘No clues in here, Boss. The guys took her iPad last night but found nothing on it of any use.’

Henrik knew that already.

He looked around the room. His daughter had the same Disney poster of Elsa from Frozen above her bed. The same pink hues everywhere, the same array of soft toys.

‘Take that, would you?’ he said to Mark, pointing to a hairbrush fuzzy with blonde hair.

They might need Matilde’s DNA at some stage, and this could be their best chance to get it.

There was a pile of drawing paper on the table, with an assortment of felt tips and colouring pencils in a mug. He put on his reading glasses and thumbed through the drawings. Nothing out of the ordinary: castles and princesses, Matilde and her family, mother, stepfather and baby brother.

‘Who’s this?’ he asked, pointing to a drawing of Matilde with a woman with dark glasses, a hat and a big blue coat. There was a large red item next to her. A pull-along suitcase?

Mark shrugged, closing the evidence bag with the hairbrush and pocketing it. ‘Maybe her grandmother was going on holiday?’

Henrik snapped a picture of the drawing with his phone. Now wasn’t a good time to ask the couple who the woman was. He could still hear Stine retching in the bathroom.

‘Check out if Simon was at his gym yesterday afternoon between three and four p.m.’

Mark nodded, making a note.

‘We need to speak to Matilde’s biological father,’ said Henrik. ‘Get him in. And check with her school whether someone made a complaint about him loitering outside the gates six months ago.’

‘Got it, Boss,’ said Mark.

Henrik felt a headache coming on, the result of another poor night’s sleep. He would need to pick up some painkillers on the way to the press conference.

A press conference during which he would have nothing to say.

His phone rang. It was Pia, the search leader at Ørstedsparken.

‘Please tell me it’s good news,’ he said, holding his breath and grimacing with his eyes closed.

‘We found a green glove, same as the ones Matilde was wearing,’ said Pia.

She hesitated for a split second, which told Henrik something bad was coming.

Something he wouldn’t want to hear.

‘It was in the lake.’

4

Every news organisation in Denmark had turned up under the pale stone colonnade circling the inner courtyard of the old police building in the centre of Copenhagen.

The journalists had formed a thick buffer in front of a row of microphone stands with colourful covers announcing the names of the country’s newspapers and broadcasters.

Jensen pushed her way through to the front, her bump parting the crowd. She was freezing in her woefully inadequate raincoat. Buying maternity clothes, like signing up for antenatal classes, was something other women did.

Women who had their act together.

She had received text messages telling her off for not attending her midwife’s appointments at Riget. How could she explain that she would rather do anything than think about what was about to happen to her?

She was scrolling for the latest headlines on her phone when she felt someone push in beside her. Turning to protest, she found herself staring into the red-bearded face of Dagbladet’s newest employee.

‘Ah, the famous Jensen,’ he said, towering above her. ‘You left without me.’

‘I wasn’t aware I was supposed to chaperone you.’

‘Touchy,’ he said. ‘I just thought, seeing as we’re partners now.’ He was wearing an enormous black puffer coat with a fur-lined hood suitable for the arctic. Smiling broadly with strong, straight teeth, he stretched out a gloved hand. ‘Jannik.’

His handshake was crushing.

‘What did you do before Dagbladet?’ she said.

‘Lots,’ he said. ‘Google me.’

Seriously?

‘I’ll take your word for it,’ she said.

He pointed to her bump. ‘When’s the big day?’

‘All too soon,’ she said, turning her face away.

He sniffed as he reached into a large bag and pulled out a microphone stand, which he proceeded to unfold.

He placed the tripod at the front alongside the others, and fixed a microphone to it, running the lead back to a camera which he hoisted onto his shoulder. On the shaft of the microphone he had placed a white sticker with Dagbladet written in bold, black felt-tip letters.

It might as well have said bargain basement journalism. Was the newspaper now so hard up that it couldn’t afford to advertise for itself?

‘I don’t do partners,’ she said.

‘Now, that’s just not true,’ said the man she would forever think of as Google Me, checking his settings. ‘I’m told you’ve been running around with Margrethe’s nephew. Now, what was his name?’ He looked up, pretending to think. ‘That’s right, Gustav.’

Her cheeks grew hot. ‘That was totally different.’ She didn’t elaborate. Margrethe hadn’t exactly given her a choice when it came to taking on Gustav as an unpaid apprentice, but none of that was Google Me’s business. ‘It was a temporary arrangement,’ she said. ‘He’s back at high school now.’

‘Where he belongs. I mean, I saw the work he did, and it was all right, but you can tell he was no professional.’

‘As opposed to you?’ She looked at him sharply. Where had Margrethe found this obnoxious man?

‘Shush,’ he said. ‘They’re starting.’

Her phone pinged, a text message from Markus, the rude receptionist at Dagbladet. He had sublet his flat to her when she first arrived in Copenhagen, only to throw her out with two days’ notice when a failed love affair had forced him to break off his round-the-world trip and return to Denmark. She had never forgiven him.

Lady named Bodil La Cour has asked for you three times. Call her back!

Jensen didn’t know anyone called Bodil La Cour. She responded with a thumbs-up emoji and slipped the phone into her pocket. When she looked up, Henrik was standing just a few feet away from her, squinting into the bright TV lights.

Her stomach lurched.

In his black leather jacket, black jeans, white shirt and beaten-up boots, he looked the same as the day they met, a lifetime ago.

He was staring down at a piece of paper in his hands with a grim expression. ‘Yesterday at around four in the afternoon, nine-year-old Matilde Clausen disappeared from the playground close to Ahlefeldtsgade in Ørstedsparken. A search has been ongoing overnight and continues today, but I regret to say that Matilde has not yet been found.’ He looked up, uncertain for a second which camera lens to look into. ‘We would like to appeal to members of the public to come forward with any information that might help us find out what happened. If you were at the playground or in the park yesterday, no matter whether you think you saw anything or not, please get in touch with us immediately. Any questions?’

‘What’s your theory?’ someone shouted.

‘Given that Matilde is just nine years old, and it’s now twenty hours since the last verified sighting of her, we have to work on the basis that a crime has been committed.’

Henrik’s eyes roamed across the crowd. He still hadn’t spotted her.

‘Do you believe that Matilde is alive?’ shouted a woman with a shrill voice.

‘We’ve no reason to believe that she isn’t.’

‘If someone abducted Matilde, wouldn’t it have been captured on CCTV?’ came a question from the back.

‘We’re working through CCTV from the area as fast as we can,’ said Henrik. ‘I can’t tell you any more at present.’

Jensen couldn’t hold it any longer. ‘How can a child just vanish?’ she shouted, sensing Google Me pointing his lens at her. ‘What do you have to say to all the parents out there who’ll wonder if their kids are safe?’

She had failed to find any recent instance like it. Most missing kids of Matilde’s age turned up within hours, except in cases where a disgruntled parent had smuggled their child out of the country. Not unheard of, but no one had suggested that had happened here.

Henrik found her eyes. Stunned, his gaze drifted downwards to her bump and back to her face. His mouth opened.

Then he snapped out of it, raised his head and looked away. ‘It should be remembered that child abductions are extremely rare,’ he said.

‘Precisely, so isn’t it more likely that Matilde went with someone she knew?’ she said.

Flustered now, Henrik addressed the crowd. ‘We’re . . . keeping an open mind. I know you all want answers. We do too, and when we have them, I promise you’ll be the first to know.’

Afterwards, Google Me nudged her with an elbow. ‘Good questions,’ he said. ‘Do you know that guy?’

‘Not really,’ she said.

It wasn’t a lie.

She had loved him like no one else. During her fifteen years in London, it had been easy to pretend that one day they could be together.

In Copenhagen, everything had become complicated.

Real.

He wasn’t the man she had thought he was.

Google Me had packed up his equipment and begun to walk away.

‘Where are you going?’ she said, frowning at him.

‘To Matilde’s parents’ place in Kleinsgade. Someone said they might make a statement after this. You coming?’

5

‘And Stine is sure it’s her daughter’s glove?’ said Henrik, closing his eyes and pinching the bridge of his nose.

It was the worst possible news.

‘Completely sure,’ said Mark. ‘Apparently, there’s a hole in the thumb that she’d been meaning to fix. She’s adamant that Matilde was wearing both gloves at the playground.’

Henrik had held back the information from the press, hoping that the glove would turn out to have nothing to do with Matilde. After all, it had been found at the opposite end of the park from the playground, floating in the water.

How had it got there? Did it mean that Matilde had walked the length of the park to the entrance furthest away from the playground, with her abductor, and dropped her glove on the way? This would only be possible if the pair had walked along the water’s edge, away from the path, and why would they have done that?

The glove could have been carried there later by an animal, perhaps a city fox, but given that the park had been crawling with people since Matilde disappeared, this didn’t seem possible.

The other possibility was that Matilde had drowned after all. Maybe she had attempted to retrieve her missing glove? Wearing winter boots and a heavy coat, she would have sunk quickly.

‘What shall I tell Stine?’ said Mark. ‘She’s very upset.’

Henrik could hear her screaming uncontrollably in the background. He had been reluctant to call in the fire-service divers until now, conscious of the distress this would cause to the family. Now they had no choice but to search the lake. With their long lenses, the TV news crews would be on to them in seconds. Speculation would start that they were looking for a body.

Besides, he knew from experience that the lake was long, and more than five metres deep in places, with thick sludge on the bottom. It wouldn’t be an easy job. ‘Tell her it doesn’t necessarily mean anything,’ he said. ‘That glove could have ended up there in lots of ways. We’re going to be searching the lake but only to exclude it from our investigation. Tell her to try to stay positive.’

As if.

He was struggling to heed his own advice.

The ham sandwich he had bought in the canteen was sitting untouched on his desk. He had a headache despite the two paracetamol he had washed down with a Coke Zero on the way back to the office.

Seeing Jensen again had thrown him. She hadn’t changed, except for the bump that stuck out from her slim frame like a football pushed under her sweatshirt.

‘There’s something else,’ said Mark. From the way his footsteps echoed, it sounded like he had left the flat and was now in the stairwell. He lowered his voice. ‘It’s Matilde’s dad. He’s a plumber, works for an industrial outfitter, but he didn’t turn up for work this morning.’

‘Understandable,’ Henrik said.

The man’s daughter was missing. Was it so strange that he hadn’t felt like hanging out with his colleagues, suffering their sympathy, their well-meaning questions?

‘His car is in the driveway outside his home, but he’s not answering the door.’

‘I see,’ said Henrik.

Perhaps Nordby had got drunk to stave off his anxiety. Strange that he wasn’t more interested in hearing news from the police.

Did it mean Simon Clausen was right that Nordby had something to do with his daughter’s disappearance after all? Had the man harmed himself, or worse?

‘And that story about him loitering outside Matilde’s school?’ said Mark on the phone. ‘Turns out it’s true. The head teacher reported him acting suspiciously, but the fact that Nordby had recently lost custody was considered a mitigating factor, and he was let go with a warning.’

Henrik got up, grabbed his leather jacket from the back of the chair. Now they had something to go on. ‘I’ll get a search warrant,’ he said. ‘Send me the address and meet me there in forty-five minutes.’

Copenhagen was choked with slow-moving traffic, the inevitable consequence of December’s shopping frenzy and the heavy rain.

Henrik hated Christmas.

The schnapps-fuelled company parties that filled the roads with drunk drivers.

Spending time with his in-laws and pretending to be happy.

And when had Christmas markets become a thing? They hadn’t been around when he was a boy, growing up in Brøndby.

Now they were everywhere, with their reindeer light sculptures and glorified garden sheds, stinking of mulled wine and frying fat.

The list of irritations was endless.

(‘You miserable git,’ said his wife in his head.)

It took him almost an hour to cross town to Tåstrup, cursing at the traffic all the way.

When he got there, the team was already assembled, waiting for his signal to force entry at the yellow-brick bungalow with the silver Kia in the driveway.

A smattering of neighbours had gathered to watch, but thankfully no reporters.

Yet.

The media circus with its unsavoury atmosphere of excitement had moved to the flat in Kleinsgade, the journalists, camera people and photographers occupying a vantage point opposite Matilde’s home.

Henrik had managed to talk Stine and Simon out of making a statement. Matilde’s stepfather was a loose cannon with his accusations against Nordby. If he and his wife were going to talk to the press, Henrik wanted to be there.

He got out of the car and approached Mark who was waiting for him outside the bungalow.

Addressing himself to one of the uniformed officers, Henrik pointed to the onlookers. ‘Get everyone’s details. Ask if they saw Nordby last night or this morning and find out if they’ve noticed anything unusual in the past few weeks.’

‘Got it.’

‘And move them back, for Christ’s sake.’

He and Mark walked up to the front door. Henrik nodded at the team that they could go ahead and force it.

It took three blows of the battering ram before the officers were able to stream inside. ‘Police. Make yourself known!’

Henrik and Mark waited for the all-clear. It came after barely a minute.

The rooms were empty and stale, but tidy. There was a stone-cold, half-full cup of coffee on the kitchen counter, reasonably fresh food in the fridge.

‘We definitely spoke to him last night?’ said Henrik.

‘Yes,’ said Mark, wide-eyed. ‘I double-checked. He was interviewed thoroughly and claimed he hadn’t seen or spoken to Matilde for months. The team had a good look round. Matilde wasn’t here.’

‘And he seemed genuinely shocked?’

Mark nodded. ‘But then you would be, if you were told that your daughter was missing, wouldn’t you?’

Or if you were a good actor, Henrik thought. The officers wouldn’t have searched all corners of the house last night; Nordby could have hidden Matilde under a bed.

Or something else entirely had happened, and they were wasting their time.

Since the press conference, more sightings had flowed in from all over Denmark of little girls in red coats. Almost all of them would turn out to be nothing, but they had to follow up on each one, which took resources they didn’t have.

Henrik donned latex gloves and went to look around the bedroom. A small double bed was pushed up against one wall. Nothing underneath it. The wardrobe was half full, a suitcase stored on top. Impossible to tell if Nordby had taken any belongings with him.

A small, black desk was pushed up under the window. Henrik bent down, squinting at the faint dust-free rectangle on the surface.

Mark came in. ‘I found this in the kitchen,’ he said, holding up a beetroot-coloured passport. ‘He can’t have been planning to go far.’

‘He took his laptop, though,’ said Henrik, pointing to the empty rectangle.

Stuck to the wall next to the desk was a faded drawing of two people with big round eyes, one with long yellow hair, one with short brown hair. The two figures were marked ‘Matilde’ and ‘Dad’.

He recognised Matilde’s hand from the drawings they had found in her bedroom.

‘Get someone to check out Nordby’s background,’ he said to Mark. ‘Relatives. Former places of work. Where he likes to hang out.’

‘Yes, Boss.’

Henrik opened the drawer in Nordby’s desk and thumbed through the old batteries, phone chargers and letters. There was a reminder to pay an electricity bill from two months ago.

He massaged his aching temples, trying to think.

There could be a thousand reasons why Nordby hadn’t turned up at work. For all they knew, the man could be out there looking for his daughter himself.

Out of habit, he moved the desk from the wall and felt along the back panel with one hand. Then he pulled out the drawer completely. The hard drive was the size of a cigarette packet and stuck to the back with gaffer tape.

Sighing, Henrik placed it into an evidence bag. He had hoped that Simon had been telling lies about Nordby, out of fear and spite.

The contents of the drive would make everything more complicated.

‘It might not be what it looks like,’ said Mark. ‘There might be an innocent explanation.’

Mark.

Always wanting to see the best in people.

He wouldn’t go far in the police with that attitude.

‘Yeah,’ Henrik said. ‘And pigs might fly.’ He went into the hallway and, twirling a finger in the air, signalled to the uniforms that it was time to leave. ‘We’re done here.’

6

WHERE IS MATILDE?

Dagbladet’s headline, in giant black capitals on a yellow banner, screamed at Jensen from her laptop screen. She had finished reading the coverage in the rest of the media. Everyone was speculating. It was now almost twenty-six hours since Matilde had disappeared, and there had been no news.

Google Me had posted a video of the press conference. He had zoomed in on Henrik’s face so far that you could see that his eyes were bloodshot and flickering left and right, the way they did when he was under pressure.

There had been police in Kleinsgade, and the curtains to the parents’ flat had been drawn. They had waited with the other reporters for over an hour for something to happen, but in the end the wet weather and boredom had chased everyone back to their offices.

Her laptop began to ping: Markus from reception calling on Teams. As she clicked on the camera icon, she remembered his text message from hours ago.

‘Your friend Bodil La Cour. You didn’t call her,’ he said, his angry face looming large on the screen.

‘I forgot,’ she said. ‘In case you hadn’t noticed, I’ve been busy covering the search for Matilde.’

‘Oh, I do apologise,’ said Markus.