Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

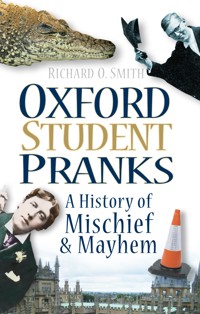

Oxford University is famed for the intelligence and innovation of its students. However, not all the undergraduates have devoted their talents to academia; instead they spent their time devising ingenious and hilarious pranks to play on their unsuspecting dons. This fascinating volume recalls some of the greatest stunts and practical jokes in the university's history, including those by Oscar Wilde, Percy Shelly, Richard Burton and Roger Bacon. Ranging from the stunt that gave Folly Bridge its name and a nineteenth-century jape that resulted in the expulsion of all the students from University College, to the long-running rivalry between Town and Gown and the exploits of the infamous Bullington Club, this enthralling work will amaze and entertain in equal measure – and may well prove a source of inspiration for current students wishing to enliven their undergraduate days.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 146

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

OXFORD

STUDENT

PRANKS

OXFORD

STUDENT

PRANKS

A History of

Mischief

& Mayhem

RICHARD O. SMITH

For Catherine Wolfe-Smith, Mum and Dad

First published 2010

Reprinted 2012, 2013

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Richard O. Smith, 2010, 2013

The right of Richard O. Smith to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5405 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Introduction

1.The Thirteenth Century

2.The Fourteenth Century

3.The Fifteenth Century

4.The Sixteenth Century

5.The Seventeenth Century

6.The Eighteenth Century

7.The Nineteenth Century

8.The Twentieth Century

9.The Twenty-First Century

About the Author

Bibliography

Oxford students. Courtesy of the Oxford Mail/Oxford Times (Newsquest Oxfordshire)

INTRODUCTION

Before you start to read this book, let’s play a quick game of word association. Oh go on, it’ll be fun. OK, I’ll start: ‘student’. Now you say a word …

Right, I’m guessing you said one, or more likely several, of the following words: dossers, drunk, lazy, drugs, over-sexed, alcohol, annoying, boozy, loud, privileged, traffic cones.

If you said any of the following words: debt, deadline, stress, tutorial, anxiety, lectures, intensive, poverty, pressure, fees, essay … then you’re (a) probably far closer to the truth than the first group and (b) almost certainly a student yourself.

If you uttered words from the first group, then you’re probably a townsperson. It isn’t necessarily mandatory to have originated from Oxford to be a townsperson; just doggedly possessing prejudice against students – or, to give them their full name: bloody students – will suffice for ‘Town’ status (as opposed to ‘Gown’, who are Oxford University and their students).

Students, of course, spend their time and money perennially stocking up on supermarket own-brand cider, rolling Rizla papers (giant size) and recording the Neighbours repeat (because it’s on at 1 p.m. and that’s far too early to expect them to be up). Other favoured activities include throwing-up near kebab vans, moving diversion signs, rolling spliffs of equivalent size to be mistaken for stock at a carpet warehouse, arranging to meet a fellow student ‘first thing tomorrow morning’ (i.e. noon) and placing impromptu traffic cone hats on any civic statues that the council has carelessly left outside on public display. Oh yes, and they also dedicate a lot of time and sweaty energy to giving each other chlamydia.

This is an accurate portrayal of the Oxford student. Or rather, it’s an inaccurate myth re-painted as reality.

Student behaviour does seem to permeate deeply into the public’s understanding of Oxford, and, for all the defined separateness that both Town and Gown have been indefatigably engaged in establishing throughout the centuries, there still exists a lazy one-size-fits-all perception of an Oxford inhabitant. Frequently, whenever I reveal that I’m an Oxonian, the encountered default response is similar to ‘you must be posh’. Often the visitor’s reference point for the city is Brideshead Revisited. Indeed, you almost encounter the belief that Oxford’s so posh we’ve probably got a Kentucky Fried Grouse in Cornmarket.

Oxford’s skyline.

Not that this perceived aloofness isn’t entirely without a justified source. The Queen’s College statutes, composed in the fourteenth century, made official provision for corporal punishment, but ‘only for the poor boys’. Brasenose, Christ Church and Corpus Christi all provided beatings for any student up to the age of twenty, with a birching administered for anyone caught conversing in English rather than Latin. (Oddly, this became an advertised fact, viewed as attracting students to their colleges, paid for by parents who approved of such discipline.)

However, the ancient glacier that is the source of this river of privilege is quickly melting and, not unlike the real, non-metaphorical glaciers, the suddenly increased rate of thawing has happened in relatively recent times, after standing frozen and unchanged for centuries.

For the the last few decades, unlike the last few centuries, Oxford has no longer been the almost exclusive preserve of upper middle-class families. Oxford is painfully aware of its requirement to become a meritocracy. The old ‘I remember your father’ college system of merely awarding places is now, mercifully, obsolete. But the public’s perception isn’t quite yet prepared to join it in becoming obsolete.

So do students behave worse these days? Well, let’s have a quick look at how they behaved in the past …

In 1301 Nicholas de Marche broke into a fellow student’s house and stabbed scholar Thomas Horncastle. The next day Thomas Horncastle violently assaulted de Marche in Schools Street. Spotting the altercation, another student intervened and was murdered by a sword-brandishing de Marche, his blood-strewn corpse abandoned in Catte Street.

Even respectable townspeople in trade could expect similar appalling treatment from students. John Crosby, a fifteenth-century student at Lincoln College, entered a glove-maker’s shop in Cornmarket and, upon learning that there was a slight delay in the gloves’ production, attempted to stab the glove maker to death (well, if you allow standards to slip …).

Not that history records the townspeople behaving much better. Richard Hawkins, a boatman based at Fisher Row on Oxford’s canal, astounded shoppers in Oxford’s Covered Market in 1789 when he offered his wife for sale by public auction. William Gibbs, a stonemason in Oxford working on repairs to the castle, purchased her for five shillings!

The behaviour of the Oxford University officials also left a lot to be desired when female students finally arrived at Oxford in the late nineteenth century. One female undergraduate was moved to fulminate in the 1980s: ‘it’s the story of the hemispheres in our skulls, not our shirts, that matters’. One British tabloid picked up the story and felt an obligation to point out that in this context hemispheres were not ‘bouncy breasts’ (which they helpfully illustrated with a photo of some pendulous breasts alongside a diagrammatic north and south hemisphere – ignoring the callous reality that the destiny of all hemispheres is to eventually go south).

Official Oxford University advice to female students in the interwar years was to ‘avoid running away from male undergraduates and townsmen, as men are aroused by the spirit of the chase’. Still, it’s somehow reassuring that the University authorities harboured an equally low view of men as they did women. Magdalen College, the last of the Oxford colleges to refuse to deliver a lecture if a woman was present, finally permitted females into its lecture halls in 1906, though not into their college until 1979.

If the townspeople and formerly chauvinistic colleges behave better nowadays, then the students certainly do too – although some modern-day freshers undoubtedly receive a culture shock after checking out of Hotel Parents. Two University College students in the early 1990s suffered the rare indignity of scouts refusing to clean their room (if you’re unfamiliar with Oxford parlance, then I should point out that a ‘scout’ is a college cleaner). Unwashed plates, stained with congealed leftovers, were poorly hidden under rugs and settee cushions – basically it was an unfit environment to keep pigs; and if they had, the RSPCA would have been forced to remove them.

And yet, unclean rooms and mild annoyances aside, Oxford students have behaved unimaginably worse in times gone by than they do today. If you’ve ever tutted at students blocking the pavement or carrying on a conversation around you whilst seemingly oblivious to your presence (students please note: simply orating ‘I was so drunk last night’ does not, in itself, constitute an anecdote), then you should read on to compare how splendidly students behave themselves now.

Richard O. Smith, 2010

A pensive gargoyle.

ONE

THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY

Although Oxford chooses to shrug off its Town and Gown divisions whenever inspected from outside (like an arguing couple who claim their spats are an inevitable part of a deeper relationship that disqualifies outsiders from understanding or advising) and the city projects an unwavering party line of unity within a shared municipal identity, rivalry between the Town and Gown has been present from the University’s inception.

The Gown’s ascendancy over the Town was practically secured as early as 1214 by the papal legate, and continued to become more concentrated over each passing decade. The townspeople would frequently retaliate. Some of their more moderate tactics included creating huge rubbish piles directly outside college gates and slaughtering livestock in the street, next to a college building and deliberately underneath a (preferably opened) scholar’s window.

CARDINAL SIN

Such was the extent of student debauchery in Oxford that word eventually reached the Vatican. A papal legate was despatched to Oxford in an attempt to sanctify the city and save its collective soul. Unsurprisingly, matters did not follow the papal plan.

Corruption reform was intended to start at Osney Abbey, where the papal legate was to reside during his stay in Oxford, and the chosen location for his first reforming speech. Oxford’s scholarly population hatched a plan that was so cunning it would have scored a ten on the Baldrick plan scale of cunning; equally it would have scored a ten on the Bal-drick plan scale of ineptitude.

The plan was: visit the cardinal daily and ply him with copious plates of food, bottles of strong wine, port and beer … and a working girl. The students were putting all their eggs in one fraying basket i.e. the entire plan pivoted on the certainty that he would be a bent papal legate. Unfortunately for the entire plan, he wasn’t. Therefore it was time for Plan B; regrettably, Plan B would also have been approved by Baldrick.

Plan B involved a sizable student army marching to Osney Abbey to engage in a mutually respectful two-way dialogue/kick his holy ass back to Rome. Sensing the students’ intentions were not peaceful, the gatemen at Osney Abbey refused the scholars entry. Tensions were escalated by several of the legate’s entourage shouting Italian-accented insults at the Oxford scholars from atop the abbey walls (this is getting so Monty Python …).

Sparked into even greater anger by the Italian taunters, the scholar army then busied themselves collecting fallen tree trunks to provide makeshift battering rams and improvised weapons. The ecclesiastical Italians similarly tooled themselves up with staves, pikes and homemade spears – similar to what one imagines the paramilitary wing of the Salvation Army would be like.

As dusk descended, the students initiated their attack. The Osney cook, who was the brother of the papal legate, had clearly studied Module One of Tactics for Defending a Medieval Castle: The Boiling Pot. Predicting the attempted student invasion of the abbey, he utilised the available time during the siege whilst the scholars were arboretum-bound collecting weapons, to order everyone to boil bowls of water or oil. As soon as the students broke through the abbey gates, he provided the prior agreed signal for the boiling liquids to cascade down onto the students below. A Welsh student was badly scolded in the face and retaliated by firing an arrow at the cook, killing him instantly.

Sensing they were outnumbered, the cardinal then raised the order for his entourage to abandon the main abbey buildings, but take refuge in the belfry. Shortly after midnight, the besieged papal delegation decided to relay a message outlining their predicament to attract help. Yet accomplishing this objective would necessitate sending a man out past the amassed students. Hence a distraction for the students was duly planned. (If only they’d had some traffic cones to put out … students are undeniably incapable of not being distracted by traffic cones.)

Fortunately for the besieged cardinal, students possess a hardwired inability to avoid alcohol too – and there were bountiful amounts in the abbey resulting form the donations/attempted bribes. Thus, as the student voices became louder as the night wore on the cardinal was elected as the man to attempt an escape, tiptoeing out of the abbey, past the drunken and loudly loquacious students, to reach the authorities grasping a written proclamation for support and reinforcements.

Using the moonlight reflected from the River Thames, the cardinal was able to escape (well, a man dressed head to foot in a bright red velvet gown accessorized with a huge red shiny hat isn’t going to be that easy to spot), whilst the boozy students were presumably too enraptured by their own conversations to notice an escapee cardinal.

The cardinal headed south along the Thames path, reaching Abingdon before dawn. Here he received word that the King was currently (and somewhat fortuitously for the cardinal) staying in nearby Wallingford. Upon hearing the cardinal’s account of the Osney Abbey events, the King’s mood quickly turned bellicose and an army, led by a royal standard bearer, was hastily despatched from the Wallingford barracks to Oxford. The professional army soon reached Osney and stormed virtually unopposed through the abbey gates, leaving the huddled and newly meek students to ponder their ironic fate of now being the besieged as opposed to the besieger of only thirty-six hours earlier.

Justice was swift and pernicious, and thirty-eight students were rounded up and sent to Wallingford to face the King. From here, they journeyed by open-top carts – their humiliation was deliberate – to London, where a delegation of high-ranking bishops intervened, eventually brokering their absolution from the legate, but only after sufficient penance had been pledged to serve as a visible punishment.

The legate may have eventually won the battle, but the war on Oxford’s immorality would not prove so accomplishable; there’s certainly been no sign of a breakthrough in the ensuing 800 years!

CAMBRIDGE’S INSALUBRIOUS ORIGINS

Oxford’s students already had form when it came to papal legates, as a townswoman (supposedly a prostitute) was killed by two students in 1209. Enraged townspeople stormed the students’ house, and, finding them out, the mob opted to kill several innocent students instead who had the misfortune to share dwellings. Fearing similar recriminations, the actual murderers considered it expedient to flee Oxford instantaneously. Once they had journeyed approximately ninety miles east, they decided it would be safe to remain there, and form their own University. That, ladies and gentleman, is how Cambridge University was founded in 1209: by two Oxford rejects who were prostitute murderers. How do you feel now, Cambridge?

As a consequence of the townspeople murdering students (not, you notice, the townswoman being slain), a papal bull was issued banning all teaching in Oxford for several months.

MACE IN YOUR FACE

Such was the deteriorating relationship between Oxford University and the townspeople, that as early as 1242 an official bailiff had been appointed, charged with the specific responsibility of keeping order between a skirmishing Town and Gown. The first holder of this newly minted bailiff’s badge was Peter Torald, who had previously been the city’s sheriff in 1225, and, although he encountered elements encumbering the peace process, he evidently performed the role with sufficient success to be subsequently twice elected as mayor.

In the thirteenth century, Oxford hosted numerous city riots that an average football hooligan would have considered unnecessarily violent and pointlessly irresponsible. On 21 February 1298, the town’s bailiff was parading through the city, proudly holding the heraldic mace of office. On reaching Carfax, he discovered a mob loitering outside St Martin’s Church (the tower still survives today, albeit rechristened Carfax Tower). The mob were students and, in some thirteenth-century equivalent of flash mobbing, had all agreed to convene at Carfax at this appointed time, with the intention of stealing the bailiff’s mace – which is such a defining student prank.

The bailiff was one Robert Worminghall, who had been elected to the role fully eight years earlier, in what I’m sure was a fair and transparent election, and utterly disconnected to the fact that his brother Phillip Worminghall was the mayor and subsequently in charge of appointing the well-remunerated post.

There are only so many students that one man can hit over the head with a sturdy – and now evidently dented – mace, and an immense discrepancy in personnel quickly occurred in the students’ favour (contemporary accounts conferred that the students were too many to comfortably count – though with medieval peasants commonly innumerate, this doesn’t help much), whilst the bailiff was left ‘with a mere handful of townspeople’. Snatching the mace, the students then committed a tactical mistake. Rather than heading back to their college bars with the mace held aloft like a captured sports trophy, they decided to remain at Carfax and await a retaliatory mob of townspeople galvanised into revenge by the circulating news.

Ringing the bells of St Martin’s summoned town reinforcement and swelled their side to an intimidating majority over the students. Several students were then attacked, with bottles being broken over heads like a big-budget Western salon fight scene. The perceived leader of the students was captured and marched towards the town jail. Just as a lengthy stay in the stocks looked likely as a plausible excuse for missing a tutorial, a further group of student reinforcements arrived, which reclaimed the personnel majority back in favour of the Gown.

Radcliffe Square – spot the traffic cone!