3,66 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pilyara Press

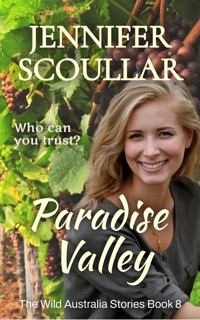

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Wild Australia Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

Ambitious country reporter Del Fisher seems to have it all. She’s just landed her dream job, along with an engagement to Nick, Winga’s most eligible bachelor and son of local mayor and mining tycoon, Carson Shaw. But Del is blindsided when a feature article and its shocking allegations about the Shaw family is published under her name.

Del and Nick’s relationship is torn apart. Devastated by the unintentional havoc she has caused, Del flees to the family farm at Berrimilla in the heart of beautiful Kingfisher Valley. Swearing that she will never write again, Del plans for a quiet life, restoring her late father’s vineyard and making peace with her estranged mother.

But when the little town is threatened by a proposed coal mine, Del steps up and leads the battle to save it. To win this fight she must enlist the support of a man who believes she betrayed him. Can Del convince Nick that she was loyal all along? And will trusting the wrong person destroy both the town and Del’s second chance at love?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

PARADISE VALLEY

THE WILD AUSTRALIA STORIES 8

JENNIFER SCOULLAR

ALSO BY JENNIFER SCOULLAR

THE WILD AUSTRALIA STORIES

Brumby’s Run

Currawong Creek

Billabong Bend

Turtle Reef

Journey’s End

Wasp Season

The Mallee Girl

THE TASMANIAN TALES

Fortune’s Son

The Lost Valley

The Memory Tree

To the Australian Conservation Foundation

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Acknowledgements

About the Author

CHAPTER1

Del Fisher sipped champagne and waited. And the longer she waited, the more her hope slipped away. She pushed aside the bowl of half-eaten chocolate-dipped strawberries. When Nick had invited her over for a special dinner, she’d been so sure. Everything pointed to him popping the question tonight: a bottle of Moët & Chandon, her favourite lobster salad, the soft strains of Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight Sonata’ sounding from inside the cottage. Stars in the night sky shone so large and low she might have touched them. Had there ever been a more romantic evening?

But so far, she’d been mistaken. Over dinner Nick hadn’t talked of love. He’d talked of a looming union dispute and his father’s plans to expand the Mount Morton mine. He’d asked about the article coming out the next day in the local paper – the last in a series Del was writing on prominent local families.

‘Have you unearthed some scandalous skeleton in our family closet?’ Nick had teased. ‘Is that why you’re shooting through on me?’

‘Honey, I’m not shooting through,’ she said. ‘Sydney is only three hours away.’

‘More like four. And when you’re on the trail of a juicy story, will you still have time for me?’

That wasn’t fair. Nick frequently spent time away on family business and she’d never complained. The twinkle in Nick’s green eyes said he wasn’t serious, but Del was in no mood for jokes. Soon she’d be taking up a position on the investigative reporting staff at the Sydney Morning Herald. It was a fabulous opportunity, but it would mean a long-distance romance. Del would miss Nick terribly. She’d feel much better, much more secure in their relationship, if they became engaged before she left.

Del caught her reflection in the crystal bowl on the table filled with floating tea light candles. Her normally straight blonde hair framed her face in soft curls. Hazel eyes gazed from behind dark mascara-tipped lashes, and sapphire earrings flashed against her olive skin. She’d even worn lipstick, which she hardly ever did outside of work. But it seemed Nick hadn’t noticed her extra effort to look good.

He finished the last lobster tail and wiped his chin with a linen napkin. ‘That was delicious, if I do say so myself.’

Del had managed a tight smile as he served her a bowl of chocolate-dipped strawberries with mascarpone cream. She was too tense to enjoy the dessert.

‘It’s not like you to leave chocky strawberries,’ said Nick, now noticing her unfinished bowl.

‘I don’t seem to have much appetite,’ she said. ‘Tired, that’s all.’

‘Well then, sweetheart, you just sit back, relax and let me clear the table.’

Del reached for his arm. ‘Can’t that wait?’

But Nick was already collecting plates and crockery, balancing dessert bowls in the crook of his elbow like an expert waiter. He disappeared inside the cottage.

Del topped up her glass and sagged back in the chair. Perhaps she should make some excuse and go home.

As Nick emerged from the house, an owl hooted from a nearby tree. He went to the porch rail and peered into the moonlit gardens, looking suddenly mysterious – a shadowy silhouette of a man. Tall, lean and straight-backed. Sandy-red hair luminous in the pale porch lights. His chiselled profile sent a familiar shiver of desire through her. Nick had no right to be so handsome.

Of course, that wasn’t the main reason why she loved him. She loved him for his intelligence and kindness and integrity. For his respect and his commitment to his family, even when they made things hard for him. Although she did wish that he’d stand up to his father more. Nick had put Carson on a pedestal that she wasn’t sure the man deserved. But Nick’s good qualities far outweighed his few faults. They were a perfect match. She was serious and he made her laugh. She obsessed over her career, and he reminded her that there was more to life than work. He rang her every day, made the best coffee ever and had perfect timing when it came to thoughtful gestures. Nick had a way of always making her feel special. Well, almost always. Not tonight.

What on earth was he doing now? Fussing about the antique jardinières ranged along the slate verandah. Pulling the odd weed from the rainbow plantings of hyacinths, anemones and early daffodils.

‘Have a look,’ he called. ‘A triple bloom. Very rare.’

‘I’ll pass,’ said Del.

‘Oh, come on, sweetheart. You’ll be impressed, I promise.’

Del breathed a small sigh, put down her champagne flute and joined him. A giant tulip grew in the centre of the pot, holding its head high above its modest companions, putting them all to shame. She had to admit it. The flower was spectacular.

Del took a closer look. The bright blue tulip, shaded with orange, seemed to glow with an inner fire. The colours reminded her of an azure kingfisher, her favourite bird. And then she recalled something her mother had once told her. There’s no such thing as a blue tulip.

Nick lightly stroked her hair, his touch electric. ‘Pick it.’

Del brushed the smooth flower with her fingertips, then plucked it from the pot by its crystal stem. Nestled within the translucent petals was a ring.

Nick extracted the jewelled band and went down on one knee. ‘Marry me,’ he said, his voice thick with emotion.

Del didn’t – couldn’t – speak. She didn’t have to. Her eyes said yes. Nick slipped the ring on her finger, and they sealed their betrothal with a kiss. She closed her eyes and relaxed into Nick’s arms. This was, without doubt, the happiest moment she’d ever known. A bright future lay ahead of them, a future filled with joy and love. Life didn’t get any better than this.

CHAPTER2

Del climbed from Nick’s bed, basking in the warm afterglow of dawn lovemaking. He reached out and murmured her name, eyes still closed. Del kissed him, whispering for him to go back to sleep. She wanted to get home – to shower and change. To properly process the events of last night. She couldn’t do that here. Nick was way too much of a distraction. After work she’d head straight back to Westbrook so they could announce their engagement to his parents. It would be a magical Saturday night – a true celebration.

Del dressed and tiptoed from the cottage, relieved to have a reasonably clear head after all the celebratory glasses of champagne. Don’t count your chickens, she told herself. Hangovers could kick in later. She glanced skywards as she hurried to her car. The day should be brightening, but a cold front had moved in overnight, bringing dark clouds and driving rain. Del turned on her car’s headlights, crossing the Red River bridge and splashing through occasional patches of water lying over the road. Hard to believe that last night’s clear skies had changed so quickly.

Del yawned, feeling wearier than she’d realised. She should have taken the day off. She should have fallen back to sleep with Nick, cradled in the protective circle of his arms. So what if she hadn’t written the ‘Dear Daisy’ agony aunt answers for Monday’s edition of the Winga Gazette? So what if she hadn’t checked the Shaw family feature for typos that might have crept in? Del switched the windscreen wipers to high and dodged an overflowing pothole. She yawned again, her eyes growing heavy. When she got home she’d catch a few winks.

During the week Del stayed at the historic Vines Guesthouse on Main Street. She parked and ran through the rain to her private door behind the rose arbour. Del had been drawn to the place by its name. She’d helped her father plant a small vineyard back at the farm, before he became too ill to tend to it.

Del rented a sitting room cum office, a little galley kitchen, and a light-filled bedroom complete with an ensuite and a huge four-poster bed. The arrangement suited her well. She didn’t have to cook or clean; Vera Bennett, the proprietor, was generally on hand to provide meals when Del wasn’t at Nick’s. Unfortunately, she was also on hand to offer opinions and advice about Del’s journalistic choices: ‘You should’ve interviewed Joan Hammond for that piece on the flower show. She knows what goes on behind the scenes, my word she does,’ or ‘You shouldn’t have been so hard on Harry Blunt. He’s a top mechanic and didn’t know those parts were stolen, I’m sure of it,’ and ‘Why not do an article on my sister? Mary’s making a go of selling her pottery online. I’m sure your readers would be interested.’

At least Vera’s scrumptious cooking made up for her interfering ways. Nobody, except perhaps Del’s own mother, could rival Vera’s prowess in the kitchen. Her eggs Benedict with homemade sourdough muffins were to die for.

Del tossed her overnight bag in a corner of the room, flopped down on the bed and took out her earrings. Dammit; she’d lost one of them. No matter – it was probably at Nick’s. She’d find it tonight.

She wanted to call her best friend, Kim Khan, and tell her the exciting news, but it was still too early in the day. A kaleidoscope of questions tumbled round her head. When would she and Nick marry? Where would they marry? What would her mother say when she knew? How would they stop Nick’s father from taking over the wedding plans? What did their future hold? And as Del pondered these unanswerable questions, she fell asleep.

Del shook water from her umbrella as she entered the Winga Gazette office. She’d woken without enough time to shower, change and get to work by nine. Del hated being late. And despite the umbrella, she’d been soaked through during the short walk from the Vines at the other end of Main Street. Wild winds drove the rain sideways. She should have taken the car.

Del dumped the dripping brolly in the stand by the door and smoothed her hair a little self-consciously. She hadn’t expected that being engaged would make her feel very different, but it did. It was a rite of passage after all, and she felt more sophisticated, more mature – as if at twenty-eight years old she’d finally grown up.

Del couldn’t resist extending her left arm a fraction and spreading her long, slim fingers to make the ring more noticeable. An unnecessary ploy, surely. The antique engagement band shone like a tiny sunrise on her finger, radiating a luminous fire in every direction. A halo of sapphires framed the brilliant centre diamond, gathering and mirroring the light, all set in 22 carat gold. How could anyone fail to notice it?

So, it was both surprising and disappointing when her entrance didn’t receive the anticipated response. Debbie, the receptionist, ignored Del’s cheery ‘Good morning’ and turned her attention to answering the phone. Not even a nod of acknowledgement. How odd!

Del passed through to the newsroom. Celia Bloom, her boss and the Gazette’s editor-in-chief, always swore that country newspapers were the beating heart of their communities. She was right, and for three years Del had thrived on the warmth and energy of this place.

But recently, she’d found that it wasn’t enough. She longed for the larger stage that Sydney would offer. No more covering local council meetings and agricultural shows. No more inventing horoscopes and doling out romantic advice in the ‘Dear Daisy’ column. She was an investigative journalist, not a hack, and she’d proved it by breaking some important stories. Maybe she’d stepped on some toes along the way, ruffled some feathers, but that couldn’t be helped. You had to be tough to reach the top in this game. And when the inevitable complaints rolled in, Celia always backed her, often saying, ‘So you hurt a few feelings. It was worth it to get the scoop.’

And Del had plenty of scoops under her belt – not an easy thing considering the limited circulation and resources of the Winga Gazette, a paper that only published four days a week. She’d followed up on rumours of cannabis plantations in Yenga National Park and her investigation had led to a major drug bust. A reader tip-off helped her expose a native bird smuggling ring. And after a spate of unexplained fish deaths, Del had uncovered the widespread, illegal dumping of chemicals along local waterways. This last story had garnered national media attention, led to a NSW government inquiry and resulted in some high-profile convictions. It’s also what had led to an offer from the Sydney Morning Herald for Del to join their reporting team. She couldn’t wait.

In the meantime, she had another two months left at the Gazette to fulfil her contract. Del planned to enjoy these last weeks, marking time with safe stories and, yes, arousing a little jealousy by her engagement to the most eligible bachelor in the district. Well, why not? There was nothing wrong with savouring some well-earned envy.

That was how Del had thought it would go. But looking around the small newsroom, she knew something was up. As a rule, it was always a hive of activity – a dozen people typing away at their desks, talking into headsets and waving sheafs of paper. People heading to the tearoom for coffee, stopping on the way to bounce ideas around with colleagues or to share a funny story – there was never any shortage of those in a small town.

But today was different. Nobody was roaming around the newsroom, chatting or laughing. All were diligently glued to their desks; the usual buzz of voices reduced to a steady murmur. Many of the staff seemed to be fielding phone calls, which usually happened when the Gazette had published something controversial. What might that be, she wondered? Del hadn’t read the latest edition yet. She hadn’t even had time to check out her feature article on the Shaw family. Nick’s father, Carson Shaw, was the popular mayor of Central Ranges. He was also its most prominent businessman, being the CEO of Westcorp Mining and Pastoral, a multi-million-dollar corporation.

The council district encompassed towns from Winga in the south, right up to the rugged forests and national parks of the Great Escarpment. Del’s article focused on the Shaws’ historic ties to the region and their development of coal mines that had provided families with jobs and prosperity for more than a hundred years. There was some local opposition brewing regarding Westcorp’s planned mine expansion in the northwest. Del hoped that her article might help to resolve it, as it emphasised the valuable contribution that Carson Shaw had made to the district.

She wandered around the dozen or so desks, flashing her ring, trying to catch someone’s eye, but everyone’s heads remained firmly down. It was almost like people were deliberately ignoring her. Perplexed, Del headed for Celia’s glass-partitioned office, grabbing a copy of the latest Gazette from a pile as she passed.

She breezed into her boss’s office. Celia was a slim, dark-haired woman of about fifty, although she didn’t look or act her age. As usual, she was overdressed: cream linen pants, a satin camisole, a leopard print jacket and a necklace of chunky wooden beads. Somehow she pulled it off.

Celia was on the phone, talking low and fast, and looking grim as she sat behind her large oak desk She didn’t even seem to notice Del come in. What was wrong with people today? Del waited impatiently, staring through the window. A sudden squall tossed the old camelia tree outside, stripping its pink petals. Rain drummed louder on the tin roof, causing Celia to raise her voice.

‘Marty, you’re the lawyer. Truth is a defence. The woman’s on the record.’ Celia looked up, saw Del and offered a strained smile. ‘Marty, I’ll call you back.’

‘Trouble?’ Del asked, not really interested. With only a few weeks left at the paper, she did not intend to get involved with one of Celia’s dramas. She extended her left hand. This time she was determined not to be ignored.

Celia saw the ring and went white. ‘Nick’s?’

Del rolled her eyes. ‘It’s an engagement ring. Who else would I be marrying?’

Celia stared at the ring and ran her tongue over her crimson lips. She always wore such outrageous lipstick. Bright colours didn’t suit middle-aged women, even ones like Celia who’d been born with natural style.

Del pulled her hand back, more puzzled than irritated now. ‘Are you going to congratulate me or not?’

Celia heaved a big sigh and pointed to the newspaper tucked under Del’s arm. ‘Have you read your feature?’

‘Not yet.’ Del tossed the Gazette onto Celia’s desk. ‘I had a late night, you know, getting engaged to the man I love? Drinking French champagne and planning our future? Activities that were a tad more important than proofreading.’ She’d run out of patience. ‘Why aren’t you happy for me? I thought we were friends.’

‘Sit down,’ said Celia, indicating a chair across from her. ‘Read the article.’

‘Why?’ Del asked in confusion. ‘I wrote it. I know what’s in it.’

‘Do you?’ Celia’s expression was almost tender as she delivered that cryptic remark. ‘Humour me, Del. Read the article.’

CHAPTER3

Del sat in the chair, unfolded the newspaper, and turned to the double-page centrespread where Celia ran the main features. What the hell? Her original headline had been replaced by the outrageous ‘Coal King has Feet of Clay’. Celia often made alterations to copy, but this was ridiculous. Del had gone out of her way to put a positive spin on everything to do with Nick’s family. It wasn’t hard; Carson Shaw was a paragon of virtue. He gave generously to charity. He ran apprenticeship programs for disadvantaged young people. He knew half of his constituents by name. Del had duly reported these things. Nothing in her article justified such a salacious header.

There were the photos she’d picked. The poignant Shaw family snap of Carson as a young man standing alongside his older brother, Bobby, and their parents. Those three had died in a shocking car accident a month after the photograph was taken, leaving Carson as the only survivor. There was the recent shot of Carson looking regal in the mayoral robe and chains, and there was an aerial shot of the Mount Morton mine – and a photo that Del didn’t recognise, the picture of a pretty blonde woman, late twenties or thereabouts, with huge hoop earrings and sad eyes. The caption read, ‘Stacey Turner, former Central Ranges Environment Officer’. Del had never heard of her. So, why did her picture accompany the article? She shot her boss a questioning glance.

‘Read,’ said a stony-faced Celia.

Del scanned the familiar text. An introduction to the Shaws’ one-hundred-and-fifty-year connection to the area and the phenomenal growth of their mining and pastoral holdings, just as she’d written it. The article continued with the tragic accident that had left Carson sole heir to a fortune, and it recounted his marriage to Natalie Astor, Nick’s mother and daughter of a former NSW premier. So far all was in order.

But when Del read the paragraph about Carson’s mayoral achievements, alarm bells sounded. She had written that Carson was elected to his current term with over eighty per cent of the popular vote. She had not written that the woman in the photograph, Stacey Turner, had an intimate relationship with Carson when she worked at the council last year – a relationship initiated by Carson, who was more than thirty years her senior.

Worse was to come as Del read on. When Carson ended the affair, Stacey alleged that he made life so difficult for her that she had to resign. ‘Our relationship was defined by a significant power imbalance and was, at times, abusive,’ Stacey was quoted. ‘Mayor Shaw took advantage of me in every way and derailed my career. It’s time I spoke up. He’s not the saint he’s made out to be.’

Del felt sick. Blood rushed in her ears and her heart pounded out of control. ‘I didn’t write this,’ she stammered, thrusting the paper forward to show her boss and pointing to the offending paragraphs.

‘No,’ said Celia, her tone almost apologetic – almost. ‘I did.’

‘You?’ Del tried to make sense of what she was hearing. ‘But it’s my article, my by-line. What do you think Nick will say when he reads it? You have to ring him right now and tell him it wasn’t me.’ Del took her phone from her pocket and found Nick’s number.

Celia got up, locked her office door, and sat back down. ‘You must admit, it’s quite a story. And the credit’s all yours.’

Del pushed her phone across the desk, adamant. ‘Ring him.’

‘No.’ Celia pushed the phone away.

‘What do you mean, no?’ said Del, beginning to panic How could her boss betray her like this? ‘I can’t let this stand. It will devastate Nick and his whole family.’ She frowned and flicked her fingers at the article. ‘And besides, I’m engaged to Carson’s son. No one in their right mind would believe that I wrote this.’

‘Are you sure?’ Celia leaned back in her chair and steepled her fingers. ‘You’re famous for chasing headlines and riding roughshod over reputations. The golden girl who always gets the scoop, right? It’s why the Sydney Morning Herald wants you. How often have you said that getting the story is all that matters?’ She gestured to the newsroom beyond her office’s glass walls, to Del’s colleagues who were wisely keeping their heads down. ‘They’ve all heard you.’

‘Who cares what they’ve heard? I didn’t write this.’

‘That might be hard to prove. Your reporting has doubled our circulation and advertising dollars, but we’ve also never had so many complaints.’

Del pursed her lips. True – she’d made some enemies along the way, attracted a few trolls. It was why she’d closed her Twitter account, and why she took a steadying breath before diving into her other social media accounts each morning.

Celia gave her a searching look. ‘You’ve been variously described as heartless, insensitive, duplicitous, pushy . . .’

‘Shut up!’ yelled Del, confusion turning to outrage. ‘Why are you doing this?’

‘Suffice to say it’s an important story – one that I knew you’d never agree to write.’

Del stood, speechless, twisting the engagement ring around and around her finger.

Celia seemed to mistake Del’s silence for a change of heart. ‘Think about it,’ she said in a wheedling tone. ‘Taking down the King of Coal is right up your alley. Your new employer will be super impressed.’

The hard-headed newshound in Del had to admit that Celia was right about one thing; this was exactly the sort of story she’d usually be itching to write. If Carson wasn’t soon to become her father-in-law. If it wouldn’t break Nick’s heart. He was devoted to his father, and it would take more than some allegations from a disgruntled former employee to sway his loyalty – or hers.

Del paced the room. She had to pull herself together, exercise some damage control and try to understand why Celia had acted in such an extraordinary way.

‘Is this woman genuine?’ asked Del as she stopped pacing.

‘There’s a short phone video of her having sex with Carson. I’ve seen it for myself. Only twenty seconds long, but it proves she’s not lying. Stacey’s since got cold feet and doesn’t want to show it to anyone else.’

‘Well, without another source, it’s just her word against his.’ Although Del knew full well that such allegations, true or not, could prompt more women to come forward. ‘What does Carson have to say about it?’

Celia shrugged. ‘I didn’t ask. First thing our mayor will know of this breaking scandal is when he reads the paper today.’

‘What!’ It was standard practice to seek statements from people prior to publishing allegations against them – not to blindside them like this. Celia had thrown every convention of ethical journalism out the window.

‘Carson should be grateful the article didn’t go further,’ said Celia. ‘A government spokesperson has confirmed that Carson is a person of interest in a confidential NSW crime and corruption investigation. That’s all we have so far.’

‘We?’ Del gave an angry snort. ‘There is no we. For some reason, you decided to publish this half-baked story and make me the fall guy. Well, it ends now.’ She shoved her phone back across the desk. ‘Ring Nick and tell him you got it wrong. Tell him this was all your idea, and that the paper will issue an apology and a full retraction.’

Celia glanced at the phone, then took a packet of cigarettes from her desk drawer, lighting up with shaky fingers. In the three years that Del had worked for the Gazette, she’d never seen her boss smoke.

Celia took a drag deep into her lungs as the rain on the roof hammered. ‘I’ve been in this game for two decades, Del, and you’re the finest investigative journalist I’ve ever seen. Try to set Nick aside for a moment and tell me – what does your instinct tell you about this story?’

Del stared at Celia, thrown by the question. It sneaked beneath her anger and outrage, causing her to momentarily take an objective view. What did her instinct say? It said that this could be a very big story indeed.

CHAPTER4

Nick raised the kitchen blind, surprised to see the gardens shrouded in sheets of rain. He opened the fridge and poured himself a pineapple juice, thinking of the previous evening, thinking of Del’s delight when she found the ring in the crystal tulip, and of his own delight when she let him slip it on her finger. This was the start of an exciting new chapter in their lives, a consolidation and strengthening of their love. He’d been debating when to pop the question for a while, and last night had been the perfect time. They’d weather the challenge of a long-distance relationship best with this commitment in place

He sculled the glass of juice and turned on the espresso machine, wishing he hadn’t drunk quite so much bubbly the previous night. The kernel of a headache was germinating in his skull. Nick sat at the kitchen bench, waited for the coffee to brew and turned on his laptop to read Del’s feature.

He logged on to the Gazette’s latest online edition and started reading. He read the lengthy piece twice, and then a third time. Shaking his head. Disbelieving. The article accused his father of being a philanderer. There’d clearly been some sort of mistake. The offending paragraphs must relate to somebody else and, due to some colossal editing error, they’d found their way into the Shaw family feature. It couldn’t be Del’s fault. He knew how she worked – she was meticulous, researching stories with the rigorous eye of a scholar crossed with an ace private detective. Checking and rechecking her facts and sources. Agonising over each word she wrote. She’d be absolutely mortified when she read it.

The ache in his temple increased a few notches. Heads must roll over this cock-up. He needed to talk to Del, and fast. Nick snatched his mobile just as it rang. Dammit – Dad. He answered, holding the phone away from his ear as the tirade began.

‘Your girlfriend’s really done it this time! First, she pries into everyone’s lives with that ridiculous chemical-dumping story. A storm in a teacup that led to charges against Scotty next door. Remember? Caused him and a lot of other decent people a truckload of trouble, but apparently it wasn’t enough. She needed more publicity, wanted to make a bigger splash. So she goes after me. And to think I cooperated with an interview. Sweet as pie she was, too. Well, at least you discovered what a snake in the grass she was before you took things any further. She won’t have her job or two cents to rub together by the time I’ve finished with her.

Nick cleared his throat. This did not seem to be the best time to announce their engagement. ‘Dad, calm down. It’s some sort of mistake. I’ll talk to Del and sort it out.’

‘You’ll do no such thing,’ Carson’s voice dripped with fury. ‘My lawyer’s already on the job. Heaven knows how Celia let such an outrage slip through. She’s usually a competent enough newspaper editor. No doubt your girlfriend went out of her way to conceal her treacherous plan.’

‘Why would Del want to damage our family?’

‘I already told you – for the publicity. Don’t be naive, son. That woman saw an opportunity to raise her profile as a reporter, so she took it. And to hell with you and the rest of us.’

‘That makes no sense. Del wouldn’t just make stuff up … ’ said Nick, battling confusion.

Carson sputtered into the phone, too angry at first to string words together. ‘Are you saying you believe her filthy lies?’

‘No … No, of course not.’ The phone beeped. Call waiting showed a second incoming call – Del.

Carson must have guessed. ‘Don’t you dare answer that!’

Nick took Del’s call. She sounded frantic, barely making any sense.

‘Yes, of course I’ve read it,’ said Nick. ‘Along with half the population of the Central Ranges, including my father. No, don’t come here—’ he began, but Del had already hung up.

Nick lived in Westbrook’s historic farm manager’s cottage, lovingly renovated and extended by his mother, Natalie. His parents lived in the property’s main house. Built circa 1840, that magnificent homestead stood on a rise, five hundred metres to the north of the cottage, overlooking Nick’s place. They shared a driveway, so there was every chance that Carson would see Del’s car arrive and come storming over before Nick had a chance to clarify things.

He tried calling Del back. She didn’t pick up. He texted her. No response. She must already be on her way. Nick swore, fixed himself a double-shot espresso and gulped it down. The scalding coffee burned his throat, but he was in too much of a hurry to care. He pulled on jeans and a T-shirt, grateful for the caffeine hit that was chasing away his hangover. Then he grabbed a coat and ran to his car. It would take twenty minutes for Del to drive to Westbrook from Winga. He had time to head her off.

Del almost skittled a pedestrian as she tore out of town, windscreen wipers working overtime. She accelerated past a stop sign, jets of water streaming under the tyres. A car beeped at her. Bloody idiot. Del beeped back, nerves stretched tight as a drum. If she didn’t speak to Nick in person soon, she’d burst.

What was it with this rain? It pelted down so hard that she could barely see the road ahead of her. Del almost missed the Westbrook turn-off. Water no longer lay across the way in shallow puddles; it inundated broad stretches of the narrow road. Despite the urgency of her mission to see Nick, she had the sense to slow down.

A fire-engine-red ute sped up behind her, just as a large dog loomed out of the rain to cross the road ahead. Del braked, causing the ute to honk loudly and make a reckless attempt to overtake. She pressed the horn, trying to warn the other driver of the animal in the middle of the road. Too late – the ute raced past. The front-seat passenger gave her the finger, then the ute’s tail-lights vanished into the gloom.

Where was the dog? She told herself it was probably fine, that it had probably leaped out of the way in time. But as her car gathered speed, Del saw a dark, sodden heap on the verge of the road. She stopped the car. What to do? She desperately wanted to keep going. After all, she hadn’t hit the dog. This wasn’t her problem. For all she knew, it was dead already.

Just as she’d convinced herself to continue on her way to Westbrook, the dog moved. It struggled to its feet, standing briefly on three legs before collapsing. Dammit, she couldn’t leave it like that. Swearing beneath her breath, Del got out of the car and ran to the injured animal. The dog trembled and briefly raised its head as she approached. Good grief, it was even larger than she’d thought. At least it had a collar; maybe the owner’s phone number was on a tag or something.

She gingerly reached out to check, but not only was the collar bare, but it also seemed too small for the dog’s neck. It dug into the skin, as if it had been put on the dog as a small puppy and hadn’t been adjusted as it grew. And she couldn’t help noticing how thin the dog was – hollow-flanked, with each rib showing. Blood streaked its shaggy grey coat, mixing with the rain in pink puddles on the roadside gravel. One front leg lay at an impossible angle. Fuck. She’d have to get it into the car somehow. God knows how. It was wounded and in pain. Probably in shock, too. She’d be lucky not to be bitten.

The rain redoubled its efforts to drown her as Del ran back to fetch the car. She parked it close beside the dog, then pulled a picnic rug from the boot. ‘Easy, boy.’ The dog cocked an ear towards her and managed a few weak thumps of its straggly tail. She tossed the blanket over it, tucking it as firmly around the dog’s head as she could. Then she took a deep breath and clumsily scooped the animal into her arms.

It uttered an agonised, ear-splitting shriek. Del screamed too, in fright, almost dropping her sodden, blood-stained burden. With a grunt she shoved the dog onto the back seat and slammed the door shut.

Now to ring Nick and explain why she’d been held up. Heaven knows what he was thinking. Del got behind the wheel, relieved to be out of the deluge. In her haste to make the call, she fumbled and dropped the phone between the driver’s seat and the centre console. It rang, but she couldn’t quite reach it to answer. It took a few precious minutes and the tip of her umbrella to finally retrieve the phone.

The missed call was from Nick. But when she tried to call him back, her phone had no service. It had lost its last bar. Reception was notoriously bad along this stretch of road. She’d just have to keep driving to Westbrook and go to the vet in Winga after talking to Nick. If the dog died in the meantime, too bad. After all, it wasn’t her responsibility. She hadn’t hit the bloody thing.

Del started the car, trying to ignore the pitiful whimpers coming from the back seat. After driving a few hundred metres, she pulled over. It was no use. Damn that dog! Uttering a string of curses, she swung the wheel hard and headed back towards town.

CHAPTER5

Even with the windscreen wipers on full blast, Nick could barely see five metres ahead of him. Lashing rain hemmed him in. Water flooded the way in low sections, and he couldn’t judge its depth. But Nick powered through, feeling reckless, his adrenaline up.

The words of Del’s article burned in his brain. He couldn’t imagine the sort of damage such a vile public slur would do to his father’s reputation. And not just to his father. The reputation of the entire Shaw family was tainted. Their business would inevitably suffer. Mud sticks, he thought, however unfair that is. And what about his mother, Natalie? She was a fragile person at the best of times, having lived with depression for many years. An incident like this was more than enough to worsen her mental health.

One of Nick’s most vivid childhood memories was of her being taken from the house by paramedics. She’d called for him as they led her away. Dad had held his shoulder. ‘Mummy’s not feeling well. She needs a rest – somewhere quiet,’ he’d said, trying to comfort his sobbing eight-year-old son. ‘She’ll be home soon.’

Nick had squirmed from his arms and climbed after his mother into the back of the ambulance. She’d clung to him, weeping into his hair, saying over and over that she didn’t want to leave him. As a child, he couldn’t understand. Mum didn’t look sick, and for a long time he blamed his father for sending her away.

As he grew older, Nick came to realise that Natalie was indeed ill. At times she seemed happy – an engaged mother and supportive wife. But at other times she’d lock herself away in the guest suite, barely eating and silent for weeks on end. A string of doctors would arrive, each – according to Carson – more useless than the previous one. Their ministrations seemed to accomplish nothing more than giving Natalie an addiction to prescription drugs.

The one treatment that seemed to help was admission to the Mayfair Clinic, an exclusive private hospital on Sydney’s North Shore. Carson was so grateful for the fine work they did there that he donated millions to the facility. Although often away for weeks at a time, Nick’s mother would be more like her old self when she returned. Nick and Carson never knew how long her recovery would last, so they always savoured that special time with her. Mum had only recently returned from the hospital again and was in better spirits than she’d been in years. Nick dreaded to think what effect that disgusting article would have on his mother’s mental health. Hopefully, Dad would be able to hide it from her until they had a satisfactory explanation.

Nick tried to keep a growing kernel of anger at bay. He hadn’t yet heard Del’s side of the story, but could she be wholly innocent? It was up to her to double and triple check her copy. And to let such a catastrophic editorial error slip through? It was unforgivable. Nick powered through low-lying water that came up to his wheel rims, too distracted to notice. He was struggling with his feelings – torn between loyalty to his family and faith in Del. He mustn’t rush to judgement. Carson would do enough of that for both of them.

Ted Barlow’s shearing sheds appeared through the rain on Nick’s right. Ted produced award-winning ultrafine fleece. Some said his Merinos grew the best wool clip in Australia. A crew had shorn his whole mob last week, all three thousand of them. Bad timing. With a cold snap and this deluge, Ted would lose more than a few head to hypothermia.

The road curved down towards the fertile flats. Red River would be running high, maybe overflowing its banks, but Nick knew the road. He’d get through, he had to. What about Del? He sped up, hoping to waylay her before she hit the worst of the water. His need to see her was like a physical pain in his chest.

Damn this weather! It was hard to get his bearings in a world turned to featureless grey. The car skidded. Had he reached the bridge? Nick wrestled with the wheel for a moment before the tyres found traction. A worm of worry squirmed in his stomach – and then it happened. The Jeep stalled. He tried the key again and again, but the engine wouldn’t turn over. Nick fought rising panic as he felt the car being buoyed by rising water – inexorably slipping sideways.

What a fool. Carson had drilled the dangers of flooded roads into Nick from childhood. ‘Never drive through water, son. A 4WD can be moved by water only forty-five centimetres deep. If it’s flooded, forget it. Deciding to keep going could be the last decision you ever make.’

Carson should know. Twenty-five years ago, his father, mining magnate Hugo Shaw, had attempted to drive through a flash flood at Manning with his wife and two sons in the car. Carson alone had survived, although his older brother, Bobby, hung on in a coma for months. It was the tragedy that had defined their family.

A wave of shame hit Nick as the car slid faster and he realised where he was – on the bridge and skating towards the edge. He’d seen Red River in flood; plunging into that surging torrent was a terrifying prospect, and the bridge had no safety rail. He tried to get out of the car, but the water was much deeper than he thought. Its weight against the vehicle made opening the door impossible. His breath came in ragged spurts. Had he learned nothing from the grief his father had endured all these years? Was he bound to repeat his grandfather’s folly?

Think, Nick told himself. He wished he’d listened more carefully to Carson. His advice had extended further than telling his son to never drive through water – although that was always the main gist of the lectures. Too late now. What else? Carson’s words came rushing back, ‘If you do get caught in the water, take off your seatbelt and roll down your windows fast. They’ll work after the car stalls, but not once water reaches the bottom of them. Its pressure forces the window against the frame, making it impossible to move, even with a manual crank.’

Nick opened the window.

‘Then grab your phone and get the hell out of there!’

Nick was a big man. It took a terrifying few minutes for him to drag himself through the narrow opening.

And the Jeep slid over the edge.

A rush of freezing water grabbed him, stealing the air from his lungs and trying to wash him away. Yet Carson’s voice in his head helped Nick keep his cool. ‘Get to the roof.’

Pain erupted in his left shoulder as a passing tree branch smashed into it, tearing his shirt to shreds and leaving the arm useless. He saved himself by clutching the roof rack with his right hand and clinging on for grim death. Centimetre by agonising centimetre, Nick hauled himself higher until at last he could clamber on top of the car.

He sat and wedged his legs beneath the rails. The storm could not drown out the sound of his pounding heart. Nick shivered and gulped deep lungfuls of air. That was a close call. And he wasn’t out of the woods yet. The force of the flood had pinned the Jeep against the bridge, preventing it from being flipped or carried away – for now. But as he watched, a timber stanchion buckled and cracked. If the bridge failed, he’d be lost.

Nick groped for the phone in his pocket, thankful it still worked after its icy dip. Shit – no reception. His frozen fingers fumbled. He lost his grip, and the phone plunged into the murky river below. Great. Just great. A lull in the rain allowed Nick a clearer view of his surroundings. Amazing, how swiftly the waters had risen. The two-metre flood-marker post was almost submerged. And then he saw something else – something that turned his stomach. Another vehicle had fallen victim to the flood. Thank God it wasn’t blue. Del’s car was blue.

The red ute lay almost fully submerged in the swollen river only metres away. Its bonnet faced his own car, which meant the ute had probably been travelling in the opposite direction when it was swept off the road. The direction Del would be taking. Nick tried to gulp down air, but his throat seemed to have closed up. The driver’s window of the ute was shattered, and a blue-sleeved arm had snaked through the jagged hole. It moved with the current in a semblance of life, looking eerily like it was waving. That could have been Del.

A shaft of shame hit him. A person had drowned, yet the first thing he’d felt was relief that it wasn’t Del. He averted his eyes from the dead man and kept watch for her car instead. He’d have to warn her. Where was she, anyway? If she’d left Winga when she’d called, she should have reached the bridge by now.

Maybe the road was already impassable. He hoped so. She could easily miss him shouting and waving in this filthy weather. And what would a girl bred in the mountains know about driving on floodplains during a rainstorm? Maybe more than I did, Nick thought ruefully. Del wasn’t the one stranded in the river.

He settled down to wait, gritting his teeth against the throbbing pain in his shoulder. Wondering how long it would be before someone found him. Thinking about the drowned car and the dead driver. Hoping that the bridge would hold.

CHAPTER6

Del stood at the front counter of the Winga Veterinary Surgery, remonstrating with Dr Stringer, drawing curious glances from others in the waiting room.

‘You don’t need my details.’ Del was sick of repeating herself. ‘It’s not my dog.’

‘Yes, I understand that,’ said the vet. ‘He’s emaciated – probably a long-term stray. But he does need urgent surgery.’

‘So?’

‘So, I’ve given him pain relief, but I can’t operate without someone taking responsibility for him. It’s a little unorthodox, but I was wondering . . . Would you be willing to?’

‘Would I be willing to what?’

‘Take responsibility for the dog.’

‘Can’t you just ring the council ranger?’

‘He’s too badly injured for the pound, and no RSPCA inspectors are available to collect him.’

‘That’s not my problem.’ Del wasn’t really listening. Nick must be wondering where the hell she was. She rang him again. Why did it keep going to voicemail? She left a fourth message.

Dr Stringer gave an impatient shake of his head. ‘If you don’t make a decision, I’ll have to put the dog down. Such a shame. He’s just a half-grown pup.’

Del turned the full force of her anger and frustration on the man. ‘I didn’t rescue that mangy mutt, at tremendous personal cost I might add, just for you to kill it less than an hour later. If I wanted it dead, I’d have left it by the side of the road. It would have saved time.’

‘So, you’re saying—’

‘I’m saying treat the bloody thing. You’re a vet, aren’t you? Then do your job.’

The man gave the young nurse a nod and she rushed off. ‘I’ll ring you,’ he called as Del disappeared out the door.

Del slowed the car. An ancient man wearing a State Emergency Service uniform waved her over. She wound down her window.

‘Road’s closed,’ he said. ‘The river’s burst its banks.’

‘But I have to get through,’ said Del. ‘I absolutely must get to Westbrook.’

‘The Shaw place?’ He rubbed his chin thoughtfully while rain poured off his orange jacket and hood. ‘Head back into town, take Nine Mile Road and cut across at the Blairgowan turn-off. It’ll take you round the back way.’

‘But that will take ages. Can’t you let me through? Please, it’s terribly important.’

‘No can do, love. Some bloke’s trapped in the floodwater between the bridge and his sinking car. He’s in a bad way, apparently. There’s a rescue underway. We keep telling folks not to drive through water, but do they listen?’

Del peered down the road through the rain. She’d reported on plenty of flood rescues. There seemed to be more than the usual number of emergency vehicles up ahead. And was that a police cordon?

‘Why’s there such a big turnout?’ she asked, professional curiosity getting the better of her.

The man leaned in close and whispered in a conspiratorial way. ‘Two cars went off that bridge. The other poor buggers didn’t make it.’ His eyes narrowed. ‘Are you okay, love? Is that blood?’

Del looked down. The dog’s blood was smeared all over her cream shirt. ‘I’m fine,’ she said, although she didn’t feel fine.

The man looked doubtful.

‘Don’t worry. It’s not my blood.’ She was in too much of a hurry to explain.

‘Well, if you’re sure … ’ He straightened his back. ‘Now, turn around, and thank your lucky stars I was here, or it might have been you in that river.’

Disappointed tears ran down her cheeks, mingling with the rain angling in through the open window. She tried one futile, final text to Nick, then reversed around and headed back towards Winga. She’d take the old man’s advice and drive to Westbrook the long way.

Del wiped her eyes. The delay couldn’t be helped, and she needed to calm down. But the shocking headline kept flashing in neon lights before her mind’s eye. ‘Coal King has Feet of Clay’. Del’s foot grew heavier on the accelerator. The longer she delayed talking to Nick, the harder it might be to convince him that she didn’t write that hateful story.

Del tried to put her fears aside and concentrate on the road ahead. Nick loved her. Once she had a chance to explain Celia’s treachery, he’d understand.

When she returned to Winga, Del dropped by the guesthouse to change. She could hardly show up at Westbrook covered in blood, even if she was in a hurry to get there. The phone rang, making her heart leap with hope. But it wasn’t Nick after all. It was Kim.

‘Oh, it’s only you,’ Del said to her friend, unable to hide her disappointment.

‘Good to hear your voice too.’ But Kim’s sarcasm was lost on Del, who simply told her what Celia had done.

‘That bitch!’ said Kim. ‘Why on earth would she do that? Can’t you sue or something?’

‘Probably. But my immediate problem is damage control. I have to convince Nick that I’m not responsible for the allegations against his father. Look, I have to go. I’ll keep you posted.’

Del put the phone down beside her laptop. She should check her work emails; there might be something from Celia. Del logged in, scrolled through the unimportant stuff, and then sucked in a quick breath. Not an email from Celia. An email from Frank Walker, the Sydney Morning Herald’s editor-in-chief himself, praising Del’s feature article. In part, it read,