21,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

A powerful study illuminates our nation's collective civic fault lines Recent events have turned the spotlight on the issue of race in modern America, and the current cultural climate calls out for more research, education, dialogue, and understanding. Race and Social Change: A Quest, A Study, A Call to Action focuses on a provocative social science experiment with the potential to address these needs. Through an analysis grounded in the perspectives of developmental psychology, adaptive leadership and complex systems theory, the inquiry at the heart of this book illuminates dynamics of race and social change in surprising and important ways. Author Max Klau explains how his own quest for insight into these matters led to the empirical study at the heart of this book, and he presents the results of years of research that integrate findings at the individual, group, and whole system levels of analysis. It's an effort to explore one of the most controversial and deeply divisive subject's in American civic life using the tools of social science and empiricism. Readers will: * Review a long tradition of classic, provocative social science experiments and learn how the study presented here extends that tradition into new and unexplored territory * Engage with findings from years of research that reveal insights into dynamics of race and social change unfolding simultaneously at the individual, group, and whole systems levels * Encounter a call to action with implications for our own personal journeys and for national policy at this critical moment in American civic life At a moment when our nation is once again bitterly divided around matters at the heart of American civic life, Race and Social Change: A Quest, A Study, A Call to Action seeks to push our collective journey forward with insights that promise to promote insight, understanding, and healing.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 527

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1: A Personal Quest

Chapter 2: Introduction to Classic Social Psychology Experiments

The Individual Level of Analysis: Obedience and Conformity

The Intergroup Level of Analysis: Studies of Intergroup Group Conflict, Cooperation, Privilege, and Oppression

Beyond Intergroup Dynamics: The Unexplored Frontier

Chapter 3: Understanding Systems, Part I: Dynamics of Complex Systems

Nonlinear Dynamics

Interdependence

Self-Organization

The “Game of Life” and Complexity in Social Systems

Introduction to Fractals

Complexity

Chapter 4: Understanding Systems, Part II: Development Toward Complexity and the Hidden Process Driving Social Change

Development of Sociopolitical Systems

Complex Systems and the Dynamics of Social Transformations

Final Thoughts on the Whole Systems Perspective

Chapter 5: The Separation Exercises

The Separation Exercise in Context: The History and Philosophy of NCCJ and Camp Anytown

Research Methodology

The Narratives

Concluding Thoughts on the Separation Exercises

Chapter 6: Findings at the Interpersonal and Intergroup Levels

The Interpersonal Level of Analysis

The Intergroup Level of Analysis

Chapter 7: The Whole System Level of Analysis

Patterns That Appear Across All Three Exercises

Exploring the Different Outcomes of the Exercises

The Paradox of Structure and Freedom

Quantitative Metrics as a Manifestation of the Quality of Presence of Directors

The Paradox of Holding Power and Love

Illuminating the Connection Between the Inner and Outer Worlds

How Wholeness Challenges Us to Radically Reframe Our Understanding of Events

Awakening to Inner Wholeness

Chapter 8: Lessons for the Real World, Part I: Seeing the System and the Process of Awakening

Seeing the System

A System of Racial Privilege and Oppression Exists

The Process of Awakening for White People

The Process of Awakening for People of Color

Awakening as an Ongoing Journey

Awakening to Internalized Privilege

Awakening to Internalized Hierarchy

Final Thoughts on Awakening to the System

Chapter 9: Lessons for the Real World, Part II: On Power, Control, and the Interconnectedness of Our Inner and Outer Worlds

Who Designed It? Understanding the Origins of the System

Understanding Historical Traumas and Glories

Who's in Charge? Understanding Individual Power, Responsibility, and Influence in the System

Understanding Inner Ways of Being and Outer Change

Understanding the Self in the System

Chapter 10: The (Dual) Call to Action

The Individual Call to Action: Undertake a Journey of Personal Awakening

The National Call to Action: Voluntary National Service as a Civic Rite of Passage

Final Thoughts on the Dual Call to Action

Closing Thought

References

Appendix A: Research Methodology Overview

Appendix B: Sample Questionnaire

Appendix C: Codes Related to Research Question 1: “How do Individuals Understand Their Involvement in Macro-Level Systemic Dynamics?”

Appendix D: Responses to Question 2: “What did it feel like being a member of your group? Why?”

Appendix E: Responses to Question 4: “Why did you not break this exercise earlier than when you did?”

Appendix F: Quantitative Attention Distribution Charts by Exercise

Appendix G: Qualitative Data Related to Question 3: “In your opinion, what was the most important group? Why?”

Acknowledgments

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Tables

Table 6.1

Table 6.2

Table 6.3

Table 6.4

Table 6.5

Table 6.6

Table 6.7

Table 7.1

List of Illustrations

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.3

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.2

Figure 4.3

Figure 4.4

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.2

Figure 6.3

Figure 7.1

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Chapter 1

Pages

i

ii

v

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

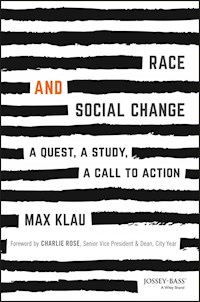

Race and Social Change

A Quest, A Study, A Call to Action

Max Klau

Copyright © 2017 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-BassA Wiley BrandOne Montgomery Street, Suite 1000, San Francisco, CA 94104-4594www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for and is available at the Library of Congress.

Cover design by Wiley

Cover Image: © Maddy_Z/iStockphoto

For Bernie and Sadie

Foreword

Iwrite this foreword in the wake of the presidential election of 2016, a year of reckoning with who we are and who we want to be as a nation. Our country chose a president who was endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan, and we are witnessing the rise of vile symbols of hate such as the swastika and the Confederate flag as well as the permission for deep-seated oppression to rear its ugly head. The United States of America is anything but united, and we face an uncertain and scary road ahead. So many people have recently asked me, “What do we say to our children?”

As the musician Common said in the theme song from the movie Glory: “Justice for all just ain't specific enough.” We have savage inequalities in our country … many are based on race and zip code. We are increasingly faced with huge gaps in income, achievement, privilege, health, and so much more. We struggle to figure out how to deal with complex challenges about identity, inclusivity, oppression, and how to bridge the divides in our nation.

America has come a long way since the ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865, which outlawed slavery in our country, but we have a long way to go to be a truly inclusive “land of the free and home of the brave.” This is as deeply entrenched as any issue facing our society today. As someone who has dedicated my entire adult life to building bridges across divides of race, class, age, gender, geography, sexuality, ability, and promoting harmony for all, I am inspired by the courage, authenticity, and passion of this book. No matter who you are or where you view these issues from, this book will challenge you to think about the world and your experiences within it in new ways.

Consider this book a new lens or a new prescription for your old lens.

Dr. Max Klau's vivid journey of discovery which you are about to read is a thoughtfully articulated and timely voyage filled with compelling insights, deep curiosity, and powerful personal vulnerability. The intriguing combination of personal soul searching, rigorous empirical research, and careful analysis as well as a poignant exploration of real-world implications result in a timely and important contribution to the conversation about equity, race, and social change in America.

Dr. Klau's expertise in adaptive leadership and his grounding in complex systems thinking are essential to understanding the variety of challenges contained in the work. Those fundamental underpinnings combined with his many years of grassroots work in the youth development and national service sectors make for a book that should be read by anyone who cares about equality, community development, and the future of race relations in our nation.

This book itself is a learning journey and a jewel for all of those folks seeking to build community, bring diverse and different people together for a common goal, and anyone who craves unity and harmony in our divided and challenged world. Dr. Max Klau presents a personal and a national call to action that needs to be heard.

Charlie Rose

Senior vice president and dean, City Year

“Justice is never given; it is exacted and the struggle must be continuous for freedom is never a final fact, but a continuing evolving process to higher and higher levels of human, social, economic, political and religious relationship.”

A. Philip Randolph

“[C]onsciousness precedes being, and not the other way around…For this reason, the salvation of this human world lies nowhere else than in the human heart, in the human power to reflect, in human meekness and in human responsibility. Without a global revolution in the sphere of human consciousness, nothing will change for the better…and the catastrophe toward which this world is headed—be it ecological, social, demographic or a general breakdown of civilization—will be unavoidable.

Vaclav Havel

“I would not have you descend into your own dream. I would have you be a conscious citizen of this terrible and beautiful world.”

Ta-Nahisi Coates, Between the World and Me

Introduction

What's true about race and social change?

It's a seemingly simple question, but what's at stake in the search for an answer is nothing less than the soul of a nation.

America came into being in a manner that was laced with paradox and hypocrisy. On the one hand, the choice to launch a revolution against the monarchy in England was inspired by the most noble and advanced ideas of the Enlightenment. The founding fathers decided to take up arms against the mightiest empire in the world out of a commitment to the following ideals:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

These words represented a revolutionary and enlightened notion in the eighteenth century, and they articulate an ideal that continues to inspire America and much of the world today.

However, at the same exact moment that the founding fathers were writing the Declaration of Independence, one could find an advertisement in the local newspaper with the following copy:

This is the inescapable truth of the founding of the United States: The most noble of humanistic ideals coexisted with the cruel reality of one of the most unjust and dehumanizing institutions in human history.

As the American experiment in democracy has unfolded, the struggle to narrow the gap between the brutal reality of racism and the inspiring aspirations of our espoused values has played out at the center of our civic life. Race relations often seemed stuck in some unjust, unchanging—and seemingly unchangeable—status quo that would endure for decades, until the nation found itself rocked by spasms of dramatic and rapid change. The institution of slavery endured from before the Revolutionary War through the founding of the nation in 1776 and on through another century, until the slowly accumulating tensions around the issue finally erupted into a Civil War that convulsed the nation. When the dust cleared and the hundreds of thousands of dead were buried, the Union prevailed and slavery officially ended.

What followed was another hundred years of the scarcely improved status quo of “Jim Crow” segregation, in which Black people continued to endure vicious discrimination. Examples of mistreatment in this era included frequent lynchings and murders with no consequences for the killers; policies such as redlining, which kept people of color segregated and impoverished; and deeply unethical medical practices such as the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. This was the American reality for nearly another century, until the nation once again found itself rocked by waves of protest and activism in the 1960s that wrought significant social change. Myriad racial injustices that had endured for decades were transformed in just a matter of years.

All that was not so long ago, and in the decades since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the issues of race and social change have remained—as ever—central to American civic life. In 2008, America elected its first Black president, and whatever you think of his politics, there can be no denying that for a nation in which Black people were once owned as slaves and legally declared to be less than human, his election was a historic moment in American history. A man who just a generation ago would have been unable to drink from the same water fountains as Whites in many states had been elected to the highest office in the land. It was an undeniable sign that some meaningful degree of social change had occurred in America.

And yet.

Today's news reports are filled with stories of unarmed Black people—mostly men—shot and killed by police: Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Dontre Hamilton, Tanisha Hamilton, Akai Gurley, Eric Harris, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile…sadly, the list could go on and on. On June 17, 2015, a twisted White supremacist joined a prayer study group at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and then shot nine Black congregants dead. It was an act of cold, vicious racial hatred that could have been ripped from the headlines of the darkest, ugliest days of Jim Crow. During the 2016 election season, we watched Black and Brown Americans get physically assaulted at multiple political rallies for the leading candidate of one of America's major political parties.

It is apparent that each of these race-related incidents functions as a real-life Rorschach test: Different people look at the same images and facts and arrive at dramatically different understandings of what it all means. Some see indisputable proof of the persistence of a vast system of racial oppression and discrimination that has endured since the nation's founding. Others see something quite different: the regrettable consequences of a flawed mental health system perhaps, incidences of excessive use of force by the police, or a lack of individual responsibility among people of color—all dynamics that are understood to be unfolding in a nation that is so color-blind and post-racial that it has twice elected a Black president. There is, it seems, no solid ground on which to stand; only the idiosyncrasies of personal experience, the shifting sands of public opinion, and the void of moral relativism.

What's true about race and social change? It's a vital question. Any answer we arrive at is sure to inform our understanding of why we find ourselves in this difficult, polarized place and how we might heal our racial wounds, live up to our highest aspirations, and step together into a brighter, more promising future.

This question has burned in my soul for decades, and it has animated a lifelong quest for insights. My search began in the nearly all-White middle class suburb of Connecticut where I grew up, where my inquiries into matters of race and social change unfolded among family and peers in classrooms, living rooms, and at kitchen tables populated by people who looked much like me. In my mid-twenties, I experienced a life-changing adventure with a group of Black and Jewish adolescents on a month-long civil rights tour across the United States that took us through the secluded back roads of Philadelphia, Mississippi; the churches of Birmingham, Alabama; the classrooms of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas; and across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. As I explain in Chapter 1, it was on that trip that the veils of blindness first began to fall away.

My quest led eventually to the classrooms of Harvard University, where my personal journey evolved into a rigorous empirical inquiry. In the early years of my doctoral studies in human development and psychology at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, I stumbled on the exercise that forms the heart of this book. I was investigating the topic of youth leadership and was conducting field research involving the observation of youth leadership programs. I wanted to know how these programs understood leadership, and then taught it to participants. It was in the course of that research that I visited a program called Camp Anytown, run by an organization now called the National Conference for Community and Justice (NCCJ). What I encountered on that visit changed the course of my life.

Camp Anytown is a week-long residential youth leadership experience that focuses on teaching young people about diversity and social justice. It occurs in multiple states across the country each year, and each Camp Anytown program brings together an extremely diverse group of 30 to 50 high school students who live together for 5 days immersed in intense experiential programming. Over the course of the week, participants engage in deep conversations about “isms” such as racism, sexism, ageism, and more in activities and sessions led by experienced educators.

On the last morning of the program, participants were separated into groups—Whites, Asians, Jews, LGBTQ, Latinos, Blacks—and told not to talk to or make eye contact with members of other groups.*The program directors then created and enforced an unjust, segregated, hierarchical social system in which the White kids experienced tremendous privilege and opportunity and the darker-skinned kids experienced discrimination and oppression. They called it the Separation Exercise, and it was designed to simulate a Jim Crow–style social system in which participants would have a chance to practice challenging these unjust norms. Challenge them they did, and over the course of just a few hours events unfolded that were at times stunningly similar to what occurred during the real-life civil rights movement.

Watching the events of that morning, I realized that Camp Anytown's Separation Exercise was essentially a simulated civil rights movement. Here, at a rustic New England summer camp, I had stumbled on an opportunity to study the process of social change in something as close to replicable research conditions as I could imagine. I wondered: What might we learn by carefully observing multiple civil rights movements in a petri dish?

The next 3 years of my life were spent developing a rigorous research methodology, observing three more of these Separation Exercises, and then analyzing the findings that emerged from across the multiple observations. I spent the next decade of my life refining my understanding of the meaning and implications of this research into the ideas presented here.

As you'll see, this analysis of these provocative exercises led to several important insights. Here are just a few that emerged from this research that you'll encounter in the pages ahead:

Dynamics of obedience and conformity play a powerful role in preserving the status quo of unjust systems. The unwillingness to question a troublesome status quo—even in the face of strong personal feelings that something is not right—is the major force in preserving current conditions. Equally important, these individual decisions contribute directly to the emergence of vast, system-wide patterns and structures in ways that most of us scarcely comprehend.

Individuals at the top of systems of privilege and oppression have very limited insight into the nature of those systems. This system blindness need not result from intentional racism or malice, but it has the effect of making it maddeningly difficult for individuals immersed in these systems to achieve a shared understanding of the reality of what's actually going on.

Individuals immersed in these systems tell stories to understand their experiences, and some of these stories hew closer to reality than others. Exploring the relationship between how individuals understand their experience and how events actually unfolded in these exercises provides important insights into matters of race and social change.

In complex social systems, some groups get enormous amounts of attention, and other groups remain completely ignored. With a higher consciousness concerning how that happens, we develop our ability to compensate for that dynamic and attain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the truth of these systems.

Achieving higher consciousness about what is true about race and social change can only occur through an experience that can best be described as a journey of awakening. This is not a process of internalizing facts and data; it is about discovering that much of what one believes to be reality is in fact an illusion. This experience of awakening unfolds for White people and people of color in ways that are distinct and different, yet also complementary and related.

Social change is nonlinear, meaning that seemingly minor events have the potential to trigger waves of dramatic transformation. This nonlinearity contributes to the emergence of “tipping points”—moments of sudden, major change that follow long periods that appear to be stuck in a state of unchanging stasis.

Social change is fractal, meaning that underneath the complexity of phenomena as diverse as feminism, civil rights, the emergence of “flat” organizations, democratic revolutions, and recent shifts in global geopolitics lies a remarkably simple and elegant process of evolutionary change. Once we learn to look for it, we see this process everywhere, unfolding with unmistakable symmetry at every scale of analysis from the interpersonal to the geopolitical.

Current-day experiences of discrimination and oppression can and often do evoke powerful memories of historical traumas. An understanding of how and why this happens reveals the fractal nature of race and social change in surprising ways. It is clear that in the absence of a clear understanding of this dynamic, we are certain to find ourselves stuck in an endless, repetitive cycle of pain and misunderstanding.

The outer-world systems and structures in which we are immersed are actually a manifestation of our innermost ways of being. In other words, inner change and outer change are not simply parallel processes; they are deeply interconnected. We do not simply live in the world; we are each actively calling forth and cocreating the world in which we are immersed, and the day-to-day world we encounter right now needs be understood as a reflection of our current state of consciousness. When we undertake the inner work required to awaken to a higher consciousness about the nature of the self and the system in which we are immersed, we will begin calling forth and cocreating transformations in the systems and structures that exist beyond the self.

In the pages ahead, I'll be demonstrating that these findings are not abstract philosophy: They are insights that emerged from empirical research and careful analysis of the data gathered from Camp Anytown Separation Exercises. This book was written to explain these insights in detail.

Here, then, is what you'll find in the pages ahead:

Chapter 1 presents a brief narrative of my own personal quest for insights regarding the workings of race and social change. It's an effort to be transparent—and a bit vulnerable—about the journey that I've had to undertake from the perspective of my personal background. I describe my own experience of awakening to a higher consciousness regarding the existence of a reality in which I have always been immersed but had not always perceived. I explain how it came to be that this personal quest led to the scientific inquiry at the heart of this book.

Chapter 2 presents an overview of a long tradition of classic social psychology experiments such as those of Stanley Milgram, Solomon Asch, Philip Zimbardo, and others. This body of research has illuminated some of the darkest shadows of human behavior in productive and compelling ways, and the Separation Exercise presented here clearly represents an extension of this tradition. A review of these past experiments provides invaluable context for understanding why this research represents a meaningful contribution to this provocative line of inquiry.

Chapter 3 presents part one of an introduction to a level of analysis that is central to this research: the whole system. Here, we encounter and explore systems dynamics such as nonlinearity, interdependence, self-organization, and the meaning of complexity itself. We also learn about fractals, a phenomenon in which the same structures or patterns appear across dramatically different scales of analysis.

Chapter 4 presents part two of this introduction to systems. Here, we learn how relatively simple human social systems develop over time into more complex social systems. And we discover that when we combine the two concepts of development toward complexity and fractals, we discover a hidden process underlying and driving social change across myriad seemingly unrelated dimensions throughout all of human history.

In Chapter 5, we encounter the detailed narratives from the three Separation Exercises at the heart of this research. We learn how the activity was run, what it was intended to achieve, and how it was studied, and how all three of these exercises unfolded. This is our chance to view these three exercises through the bird's-eye view of the team of researchers who observed and documented the three separate activities.

Chapter 6 presents the findings that emerged from the Separation Exercise research related to the first two levels of analysis that were explored in this study. At the interpersonal level, how did participants understand their experiences? How did they feel about being a member of their particular group? What were their reasons for challenging—or not challenging—the unjust norms of the system? In addition, at the intergroup level, what did participants think about the other groups in the system? What groups received attention in the system, and which were ignored? Why?

In Chapter 7, we take a look at lessons learned at the third and highest level of analysis: the whole system. First, we'll explore what patterns appeared across all three exercises and what shared narrative of social change emerged across all three exercises. Then, we'll dive into what turns out to be a far more complex question: Why did each exercise unfold so differently? We'll investigate some seemingly paradoxical insights that explain dynamics unfolding at this highest level of analysis.

Chapters 8 and 9 explore the real-world implications of this research. In Chapter 8, I discuss the foundational need to recognize the existence of a system of racial privilege and oppression in the real world and deepen our understanding of how to think about that system. I also discuss the process of awakening that we must undergo to arrive at a higher consciousness regarding these systems and share some important moments in my own ongoing journey of awakening. In Chapter 9, we explore questions of power and control: Who designed the system? Who is in charge? And what are the implications of the finding that there is a connection between our inner ways of being and the outer-world systems in which we are immersed?

The book will conclude with Chapter 10, in which I present a dual call to action on an individual and a national dimension based on the insights presented in this book.

Before wrapping up this introduction, I'll offer a few more thoughts intended to orient you, the reader, to the journey ahead. First, who am I? Second, who did I write this book for? And third, how do I understand the purpose of this book? Once these questions are answered, we'll be ready to set off on this journey together.

First, who am I?

I am a White, middle class, Jewish, straight, cisgendered male. I'm married and I live with my wife and kids in a Boston suburb. The path I have walked in my journey has been that of awakening from a place of privilege, with the inevitable result being that I have had to learn a great deal about race and social change through dialogue with people of color as opposed to lessons learned through direct personal experience.

I have completed a doctorate of education (EdD) that involved a dual focus on developmental psychology and leadership—specifically, the adaptive leadership model developed by Ronald Heifetz. Because both of these disciplines inform the ideas presented in the pages ahead in foundational ways, they merit some brief explanation.

As a developmental psychologist, I've been trained to view life as an ongoing developmental process unfolding over the course of time. This process flows generally from a state of relative simplicity toward a transformed state of greater complexity. The developmental process is rarely a simple, linear progression, however. Development often happens in fits and starts; metaphorically speaking, life takes two steps forward and one step back. Long periods may go by with little development occurring to be followed by rapid spurts of change. Also, development is not inevitable. Under the right conditions, it may advance rapidly; under the wrong conditions, it may be delayed, arrested, or reversed. This professional training to view all of life as undergoing a constantly unfolding process of developmental change is foundational to the ideas presented in the pages ahead.

My training in adaptive leadership results in two key theoretical distinctions that inform the way I understand the world. First, I have learned to make a distinction between two types of challenges: technical and adaptive. Technical challenges are defined by the fact that we understand the problem and already have in our repertoire a set of responses that enable us to effectively address the problem. Adaptive challenges are different. With an adaptive challenge, the nature of the problem itself is often not at all clear, and whatever technical solutions we've already mastered are insufficient or ineffective at addressing the challenge. I have come to view matters of race and social change as adaptive challenges: There is no clear agreement on the nature of challenges embedded in these matters, there are no simple technical solutions that will quickly transform race relations in this nation, and any meaningful change will involve transforming some long-standing beliefs, values, and norms at work in our civic life.

The second theoretical distinction that I have learned to make involves differentiating between authority and leadership. Although we often conflate the two terms and use them interchangeably, that is problematic—especially when trying to understand matters of race and social change. According to this model, authority is a formal position of power in a community or organization. It is the president, CEO, principal, teacher…whoever is in the box at the top of the hierarchy on the organizational chart. Leadership is something different: It is an activity that can be undertaken by anyone in the system intended to mobilize a group to address an adaptive challenge. An individual in a position of authority may try to exercise leadership…but that individual may also use authority to preserve a problematic status quo. And one need not be in that position of formal authority to attempt to exercise leadership. With this theoretical distinction, we have a powerful way of understanding the process of social change throughout history. After all, individuals such as Gandhi, Rosa Parks, and Malala Yousafzai did not have positions of formal authority, yet they exercised tremendous leadership.

Over the course of conducting the research presented here, I've had to engage deeply with some other subject areas as well. As you'll see, this research is grounded in the fields of social psychology and complex systems, and I've sought to digest enough of those literatures for this work to represent a contribution to those fields. I've worked hard to weave together insights gleaned from fields such as critical race theory, organizational development, personal transformation, and studying the lives of towering figures such as Nelson Mandela and Malcolm X.

I am keenly aware of the fact that the terrain explored in this book relates to a great many other disciplines that focus on matters of race and social change. The Separation Exercises at the center of this book would provide a rich source of exploration for scholars of critical race theory; racial identity development; gender studies; queer studies; group psychology; the history, psychology, and sociology of social movements; adolescent and adult development; and much, much more. On many occasions, I make passing references to bodies of literature with which I have some familiarity and are relevant to the matter at hand, but those references are undeniably cursory and the attempt to reference related fields is incomplete.

I understand this to be the inevitable result of grounding this research in the fields of leadership and complex systems: The opportunity inherent in these interdisciplinary approaches is the chance to explore dynamics that transcend traditional boundaries in ways that provide important new perspectives. The risk is that anyone working in these fields opens themselves up to the critique by scholars in dozens of related fields that they are uninformed dilettantes because they do not know and say more about disciplines that are undeniably directly relevant to the matter at hand.

So be it. If I have learned anything from this quest, it is that we live our lives immersed in a web of relationships so vast, complex, interconnected, and interdependent that it can never be described or revealed in its totality. As with all mysteries that transcend the limits of human understanding, these matters can only be encountered properly through the cultivation of humility. Given that understanding of the deepest nature of these phenomena, my intention here is to make a contribution, albeit in some small and inescapably limited way. I am the first to declare that there is a great deal more to learn about all of this, and I look forward to continuing my own learning journey in the years ahead.

In my professional life, I have spent the last 10 years working for City Year, a national service organization that engages young adults (ages 17–24) in a demanding year of full-time service focused on keeping students in high needs schools on track to graduate from high school. I've spent the last decade working with the thousands of diverse, idealistic young adults—and the remarkable staff members who support them—serving in urban schools across the nation in a pragmatic, collaborative, and data-driven effort to positively transform the nation's high school drop-out crisis. Currently, I'm involved in a non-partisan effort to recruit and support alumni of service programs (both military veterans and alumni of civilian service programs like AmeriCorps and Peace Corps) to run for political office. This focus on developing leaders through service is the theme that runs throughout my career.

Regarding the question of who I wrote this book for, I've kept an image of a particular audience in mind throughout the writing process. Although I know that this book will be read, most likely, by individual readers, the audience I've been writing for in my mind has not been a solitary individual but a small, highly diverse group of thoughtful, engaged, concerned citizens. They might be university students discussing course work in a classroom, activists connecting across communities in a local coffee shop, employees connecting across silos in a meeting room, congregants gathering in fellowship in the basement of their place of worship, engaged citizens gathered for an evening in a local school cafeteria, and elected officials coming together in a town hall or state capitol. The key detail is that the group is, in some infinitely variable way, a microcosm of the whole that is the United States: individuals of different races, creeds, backgrounds, sexual orientations, and beliefs sitting together in a circle with a desire to inquire, learn, and connect in a manner that happens far too rarely in our civic life today.

These readers feel called to engage with this topic out of a deep sense of pain at the discord, coarseness, violence, and suffering so prevalent in our civic life today, mixed with a deep pride in this country and an unshakeable idealism regarding the values and ideals it stands for. They dream of creating something better for themselves and for their children, despite the sense that the path out of all this darkness, strife, and confusion is not at all clear. Although they may not understand themselves in these terms, they are, in essence, a fractal microcosm of a society yearning for wholeness amidst the pain of disconnection. They are the incomplete parts of a living whole system that simply does not know itself fully yet and whose capacity to heal and thrive depends on achieving a deeper awareness and higher consciousness of the reality of that wholeness. It is my hope that if this group were to come together to share their reactions and responses to the ideas in the pages ahead, they might take a few meaningful steps toward not only understanding that wholeness but also actually experiencing it.

As a final thought and to answer the third question about the purpose of this book, I'll state that the process that led to this book was most eloquently illuminated by the Bohemian-Austrian mystical poet Rainer Maria Rilke (2013), who shared the following advice with a fellow poet in 1903:

I would like to beg you, dear Sir, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don't search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.

After decades of living the question of what's true about race and social change? I feel that I have—at long last—lived into an answer that feels thorough and complete enough to merit sharing with the world. The insights presented here are offered in a spirit of humility, with a keen awareness that there is much about race and social change that I do not yet understand and have yet to learn. Still, it is my hope that this collection of insights gained over the course of a decades-long journey of awakening might represent a productive contribution to a dialogue about a matter of central importance to the past, present, and future of our nation.

Note

*

At this early moment in the book, I'd like to offer a word of explanation about the choice to capitalize the names of all different races. In the writing process, I learned that some of these words—such as

Latino

or

Jewish

are nearly always capitalized, and others—such as

black

or

white

—are not always capitalized. Early drafts featuring some races with capitalization and others without seemed inappropriate, as though groups with capitalized names were more worthy of respect than groups without. I have chosen, therefore, to capitalize the names of all races. It reflects an intention to refer to all these different groups with a shared and equivalent sense of respect.

1A Personal Quest

Ican't tell you precisely when the quest began, but I can share a moment when the first of a great many veils of blindness and ignorance fell from my vision, illuminating the first small slivers of insight.

It was in the basement of a college dorm in Virginia. I was working as a group leader for an organization called Operating Understanding DC—more often known by its acronym, OUDC—and we were 3 days into a month-long bus journey across the United States. Our travels would take us through some of the most important sites in the history of America's civil rights struggle: Birmingham and Montgomery, Alabama; Little Rock, Arkansas; and Philadelphia, Mississippi. OUDC brought together a group of 30 teens from the greater Washington, DC, area; half of them were Jewish, half of them were Black, and one or two were both. Together, we would encounter these historic sites and meet some of the courageous individuals who made these towns so significant. As a group, we would engage in an intense, honest, searching dialogue about race and social change that would unfold in an essentially unbroken stream for the entire 30 days.

We were just a couple days into the trip and still early in the process of evolving our group dynamic. The program this evening was a “fishbowl” activity that would be led by OUDC's remarkable founder, an endlessly colorful and energetic woman named Karen Kalish. She was Jewish, with a soul that burned for racial equality and social justice. It was thanks to her that we were all gathered that evening in the basement lounge of a college dorm in Virginia.

For this fishbowl activity, a group of six Black participants (three young men and three young women) were seated in an inner circle, with the rest of the group arranged in a larger circle surrounding them. Those of us in the outer circle were told to just listen; all the talking would be done by the six Black teens in the inner circle, who were invited to discuss their experiences growing up Black in Washington, DC.

The conversation began with a tone that was light and casual, but it didn't stay that way for long. In just a few minutes, the conversation entered terrain that I have since come to recognize as a space of sacred truth: a place where one can feel—in one's innermost heart—that truth is being spoken and that defenses are being lowered as people risk levels of honesty and vulnerability that are almost never revealed in day-to-day life. In that space, real tears began to flow, along with the sort of utterly genuine laughter and joy that emerges spontaneously in moments of authentic human connection. I had explored race in an intellectual way many, many times in the past via books, documentaries, and discussions with others who shared my own background. But it was in this space that I first had a significant, genuine, fully human experience with the “other” and had a flesh-and-blood encounter with all the bitter, painful, difficult truths and all the awe-inspiring resilience and spiritual strength that animated the inner lives of this group of young Black Americans.

The young people told stories of walking into stores and being stopped by store employees who suspected them of shoplifting. There was no ignoring the fact that if they walked into the store with White friends, the White friends were never stopped and questioned. They had stories of being pulled over while driving, even though they were certain they were going no faster than the speed limit to avoid exactly this outcome. They talked about struggling to get the sort of entry-level jobs in retail or restaurants that White friends seemed to land with minimal effort. They shared stories of parents struggling to pay the rent and of how the adults in their lives so often found their opportunities limited and constrained in a thousand small but significant ways.

In time, the deeper complexities of their experiences began to surface. A light-skinned Black girl noted that she was rarely stopped by store employees, even when she was with darker-skinned Black friends who were stopped. Part of her felt lucky to be able to “pass”—to move through the world enjoying the privileges that come with people simply assuming that she was trustworthy. But that privilege and relative ease of movement came with some heavy baggage. She struggled with guilt every time her darker-skinned friends had to endure some injustice that she had been spared, and she had to deal with Black friends regularly making comments suggesting that she wasn't “really” Black. To be light-skinned, I learned, was a blessing and a curse in the life of a young woman of color.

The fishbowl lasted for at least 2 hours, and as I listened, a whole world of complexity, pain, resilience, and emotional truth about the lived experience of young people of color in America was revealed to me for the first time. And what I remember most about night was the thought that kept running through my head again and again as the discussion unfolded: I had no idea.

I had no idea how frequently people of color encountered discrimination and barriers to opportunity in their lives. I had no idea how much pain these incidents caused. I had no idea that differences in skin color created such social complexities in the lives of kids of color. I had no idea how much strength and wisdom and humor was required to stay healthy and resilient in the face of these relentless challenges. I had no idea how any of this felt, or how any of this worked, or what any of this demanded of these kids, because I had never really had to worry about any of it. I had no idea.

And I was the group leader.

I felt—and I still feel—that I was hired with good reason. Similar to Karen Kalish, I was a Jew with a burning passion for social justice and a deep desire to promote racial equality. I was appalled by America's history of slavery and viewed leading figures of the civil rights movement such as Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. as personal heroes. I had worked extensively with communities of color while participating in a year-long service program in Israel, and later I managed young adults engaged in similar service as a group leader. I even had a remarkable job that allowed me to spend 4 months traveling around America with an Ethiopian Israeli colleague and friend; together, we gave speeches and raised money to support the Ethiopian community in Israel. On my résumé, at least, I was no stranger to matters of race. At the age of 27, I could honestly claim years of involvement in service, youth development, and social justice education. Karen Kalish had every reason to hire me for that job. And yet still: I had no idea.

That night, my hunger to learn more was piqued, and the weeks that followed provided a treasure trove of opportunities for learning, dialogue, and understanding. We had amazing experiences, such as meeting the mother of civil rights worker Andrew Goodman, one of the three young organizers who was killed in 1968 while advocating for voting rights for people of color in Philadelphia, Mississippi. That night, we stayed overnight in the homes of Black residents of Philadelphia who had agreed to host our group. Our host offered to take us on a tour of how it all happened, so we got into his car in the pitch-black Mississippi night and he drove us around: Here was the jail where the three young men were being held, and where they were pulled out of their cell by a White mob; here was spot where they were pulled from the car, beaten, and killed; here was the spot where their bodies were buried. Driving through the thick woods on the darkened back roads of rural Mississippi, it was impossible to not feel a small dose of the terror those three young men must have felt that night, and I was left struggling mightily with the question of how a group of ordinary White people with jobs and families could transform into that kind of rageful, hateful, murderous mob.

While on the bus, we watched Spike Lee's powerful documentary Four Little Girls about the four Black girls killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The movie ended just as the bus pulled to a stop…in the parking lot of the 16th Street Baptist Church. We walked inside and immediately participated in a panel discussion with community members, including a parent of one of the little girls. Days later we walked across the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama, Blacks and Jews holding hands, singing “We Shall Overcome.”

It was a remarkable, month-long, encounter with something I can only call the civic sacred. Every day, we met seemingly ordinary men and women who had summoned levels of courage, creativity, and commitment that literally transformed a nation and inspired the world. In confronting some of America's darkest shadows of hate and intolerance, they had elevated everyday civic spaces—bridges, buses, roads, coffee counters—into sites that properly can be called sacred. Despite—actually because of—all the emotional complexity evoked by confronting this history, it was a wonder to encounter it all and a blessing to experience it as a member of this diverse group of young people.

The conversations begun that night with the fishbowl continued all month long as together we processed each day's experiences and learned more and more about how we all saw and experienced the world. Despite all my interest in these matters over the years, I realized that I had reached the age of 27 without ever having had the chance to have these kinds of deep, authentic discussions about race with people of color. I remember feeling waves of gratitude at finally having the chance to explore all this with people who didn't look just like me. It was a peak life experience, and to this day I remain amazed at how rare it is to encounter these spaces of authentic connection and deep dialogue about race with “the other” and how essential they are to achieving a genuine understanding of what is true about race and social change in American civic life today.

I have said that my OUDC experience was not the moment the quest began; I had been passionate about matters of race and social change for years before that remarkable experience. But it was beyond a doubt a pivotal moment in my journey. It was the time when I saw clearly just how blind I was to how race and social change actually worked. And it was the experience that crystallized the questions that would burn in my soul and animate much of the next decade of my life:

How does this whole thingwork?What's really true about race and social change in America?

Just a few months after completing OUDC, I started graduate school at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Harvard was a remarkable experience. I took classes with titles such as “Education for Social Change,” “Promoting Morality in Children and Adolescents,” “Exercising Leadership, Mobilizing Group Resources,” and “Moral Development.” I was immersed in topics I yearned to learn more about and was privileged to explore it all as part of an extremely diverse student body. Harvard is surely an elite institution, and I have no doubt that a great many students and professors could make compelling arguments about all the ways the school does not adequately confront the realities of issues such as race, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and more. All I can say is that in my experience, I was pushed, challenged, and transformed by encounters with diverse peers on a nearly daily basis. My studies were so engaging that I knew almost instantly that a one-year master's program would not be enough; I applied to the doctoral program in human development and psychology and was thrilled when I heard the news that I had been accepted. I now had at least five more years to seek answers to the questions at the heart of my quest.

In those first years of my doctoral studies, the learning was intense and exciting. The professors were experts in their fields, and I was surrounded by hard-working, passionate, inspiring peers eager to dive into debate and dialogue. Despite all I was learning, though, something felt incomplete. In hindsight I realize that I felt a lot like the blind men in the well-known parable of the elephant, although I wasn't really conscious of the metaphor at the moment.

In that story, one individual touches the animal's leg and declares that the elephant is like a pillar, another touches the ear and declares the animal to be like a hand fan, another touches the tail and declares the animal to be like a rope. The blind men descend into a bitter argument about who is right, until a wise man appears and illuminates the truth: They are all correct, but they have all encountered different, limited aspects of what it is in fact a cohesive, larger truth.

So it was with my studies of race and social change. I listened to professors and peers share different insights and perspectives every day, and I realized quickly that it made no sense to assert that their experience was “wrong”; it was their experience, as true to them as my own experience was to myself. But how did all these perspectives on truth fit together?

I knew from personal experience that when it came to matters of race and social change, as a White male I arrived at adulthood blind to how things worked in profound and surprising ways, despite my good intensions and passion for these issues. I knew from many meaningful encounters with people of color that for them, blindness to race was impossible. Race was something they could never escape; they confronted discrimination and felt their “otherness” on a near daily basis. Every day brought a new lesson in the complexity of how race and social change was experienced; Asians, Latinos, Blacks, LGBTQ students, students of mixed ethnicity, as well as atheists and students deeply committed to their faiths all had distinctive stories to share.

I quickly learned that trying to absorb more about any of these issues inevitably opened up entirely new frontiers of complexity. Consider, for example, the effort to gain a deeper understanding of the Asian experience of race and social change in America. It didn't take long to encounter that there is no single monolithic “Asian” experience; individuals from Japan, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and other Asian nations have their own identities, their own histories, and their own truths to share. The same goes for Latinos and Blacks; to inquire more deeply into any of these groups is to encounter a vast landscape of subgroups, each with their own experiences, histories, and traditions. It soon became obvious that it was quite simply impossible to truly understand all of this complexity; the full diversity of humanity is too vast for any one person to grasp. But I could certainly learn to expect that complexity and resist the tendency to think and talk about individuals as representing monolithic groups that have never really existed.