28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

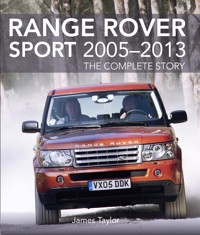

When the Range Rover Sport was launched in 2005, it was aimed at a new group of customers who in many cases would never have considered a Land Rover product before. These customers wanted and could afford a luxurious vehicle that was expensive to run; but they also wanted a very personalized vehicle that did not have the rather grand and conservative connotations of the full-size Range Rover. Brasher and more glamorous than its older sibling, the Sport was soon adopted by celebrities and others who expected to be noticed. Range Rover Sport - The Complete Story is the first book devoted specifically to the first-generation Range Rover Sport. It tells the story behind the development and launch of the vehicle; it explains the market reaction, including contemporary press reviews; provides details of each model with technical specification tables and colour and trip options; lists production figures and VIN identification and dating; details prices and sales figures for the UK, USA and Canada and finally, includes a useful chapter on buying and owning.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

RANGE ROVERSPORT 2005–2013

THE COMPLETE STORY

James Taylor

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© James Taylor 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 660 9

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Range Rover Sport Timeline

CHAPTER 1

THE BACKGROUND STORY

CHAPTER 2

EARLY DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

CHAPTER 3

THE EARLY SPORT, 2005–2006

CHAPTER 4

NEW IDEAS, NEW CHALLENGES, 2007–2009

CHAPTER 5

MORE ‘PREMIUM’: THE 2010 MODELS

CHAPTER 6

THE FINAL MODELS, 2011–2013

CHAPTER 7

BUILDING THE RANGE ROVER SPORT

CHAPTER 8

THE NORTH AMERICAN MODELS, 2005–2013

CHAPTER 9

THE L320 AFTERMARKET SPECIALISTS

CHAPTER 10

BUYING AND OWNING AN L320 SPORT

APPENDIX I

PRODUCTION FIGURES

APPENDIX II

VIN IDENTIFICATION AND DATING

APPENDIX III

RANGE ROVER SPORT PRICES IN THE UK

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As far as I’m aware, this is the first book ever devoted specifically to the first-generation Range Rover Sport. This was a hugely popular model, but it was also controversial: associating the word ‘sport’ with a Land Rover product immediately raised the hackles of long-standing devotees of the marque, and it took many of them a long time to come to terms with the idea.

It took me a while to get to grips with the Sport, too. When it was released in 2005 I was editor of Land Rover Enthusiast magazine, and in a spirit of egalitarianism (which I later regretted) I asked my deputy, Simon Hodder, to go and check out the new model at the press launch in Catalonia. Fortunately, a good relationship with Land Rover themselves enabled me to borrow a TDV6 model for a family holiday in France a year or so later, and I must say that I was impressed. It felt good, not too big like the latest full-size Range Rover, and it went and handled well. Later experience with examples off-road convinced me that this was a proper Land Rover, and a good one.

Of course, its appeal to celebrities gave the Sport a certain image, and a lot of traditional Land Rover folk had difficulties with that. Over the years, though, the Sport has gradually earned itself a place within the Land Rover community. More important from Land Rover’s point of view is that this model attracted a whole new set of buyers who had probably never considered buying a Land Rover before, and many of them were convinced enough to stay with the marque. I’m not in any doubt that the first-generation Sport was an enormously important model for Land Rover, and that the company would not be in the largely enviable position it enjoys today without it.

It’s customary to include a list of people to thank in the introduction to a book like this. Quite frankly, there are too many to remember, but I am very grateful indeed to the many Land Rover employees who talked to me about the Sport, to the company’s press office who provided me with information and photographs when the vehicles were new and who also lent me several examples to try, and to several makers or owners of aftermarket conversions who gave me an insight into what their sectors of the market really appreciated about the model. Lastly, special thanks go to my colleague Jerome André for providing information about the Sport in the USA, which the JLR press office in the USA was unable to source.

James Taylor,Oxfordshire, April 2019

RANGE ROVER SPORT TIMELINE

2004, January

Preview of the Range Stormer concept at Detroit Motor Show

2005, January

Introduction of the Range Rover Sport at Detroit Motor Show

2005, June

Start of showroom sales: the 2.7-litre TDV6, 4.4-litre V8 and 4.2-litre Supercharged V8 models

2006, November

Introduction of 3.6-litre TDV8 models

2007, September

4.4-litre V8 models withdrawn from Europe but remained available elsewhere

2009, June

Facelifted ‘2010’ models introduced with 3.0-litre TDV6 and 5.0-litre supercharged V8 engines; 3.6-litre TDV8 and 5.0-litre V8 engines available for export

2010, September

4.4-litre TDV8 replaced 3.6-litre, for export only

2011, July

3.0-litre SDV6 engine replaced 3.0-litre TDV6 for most markets

2013, March

Final first-generation Range Rover Sport built

CHAPTER ONE

THE BACKGROUND STORY

To anyone whose first acquaintance with the Land Rover marque was a Range Rover Sport, it probably seems incredible that this high-performance modern SUV (Sport Utility Vehicle) was ultimately derived from a farm runabout. But in order to understand why the Sport became the vehicle it was, it really does help to understand something of the history behind it. A knowledge of that history also helps to explain why many long-term Land Rover devotees turned their noses up at the Sport when it first appeared, for the Sport was the first step in a new direction for Land Rover. It was also a very important turning point for the company, and its success underpinned the new direction that Land Rover would take in the later 2000s – and would take very successfully.

ORIGINS OF THE ROVER COMPANY

Back, though, to that farm runabout, which was the start of the whole Land Rover story in 1948. Back, too, to a British motor manufacturer that no longer exists, but in 1948 was a highly respected independent maker of cars for the professional classes. The Rover Company, like many other car makers, could trace its origins back to the bicycle era of the late nineteenth century; it began to make cars in 1904, and after some difficult times in the 1920s, had returned to prosperity with a strong product line in the 1930s.

Behind Rover’s revival were two brothers. The older was Spencer Wilks, whose expertise was in business management, and who became Rover’s Managing Director. The younger was Maurice Wilks, a talented engineer who took over the leadership of the engineering teams at Rover. It was the solid reputation that these two – and a similarly talented if rather conservative management team – built for Rover that persuaded the Air Ministry to ask the company to manage a pair of ‘shadow factories’ on its behalf in the late 1930s.

The ‘shadow factories’ came about as the threat of a second war with Germany became more and more real. It was already clear that aircraft would play a major role in any future war, and the Air Ministry wanted to ensure that Britain’s ability to produce new warplanes could not be knocked out by enemy bombing. The solution was to disperse aircraft production facilities around the country, by building new factories to ‘shadow’ those of the established manufacturers. These factories were to be managed by Britain’s car makers, who had the experience necessary to oversee large-scale industrial production.

Rover was allocated two factories, one at Acocks Green near Birmingham, and the other at Solihull to the south-east of that city. When war did come in 1939, it proved every bit as devastating as the government had feared. Rover’s headquarters and assembly plant in Coventry were rendered unusable during the ‘blitz’ bombing of that city in 1940, and those staff who had not been called up to fight were dispersed elsewhere. Many of the engineers went north, to assist in the development of Frank Whittle’s jet aircraft engine at a series of locations in old textile mills in Lancashire and Yorkshire. Car development stopped altogether.

The former ‘shadow’ factory at Lode Lane in Solihull became Rover’s headquarters in the mid-1940s; this picture dates from shortly after that time.

The main administrative block is readily recognizable in this more recent picture taken at the Solihull plant, but the rest of the site has been extensively redeveloped over the years.

THE LAND ROVER IS BORN

As the war ended in 1945, Rover’s primary job was to return to normality. But it would have to be a new normality. There was no factory or headquarters to return to, and the company’s directors seized upon the government’s offer of moving into the former aero-engine factory at Solihull. So it was here that plans for new post-war models were developed, although the task was a difficult one. Even though car production in Europe had been at a standstill for some years, car production in the USA had not been halted until 1942, and when the USA returned to building new models in 1945, those new models had features that were far in advance of anything that Europe could offer.

For Rover, the situation was critical. Out of necessity, the British government was also rationing supplies of raw materials such as steel, and manufacturers were to be allocated supplies on the basis of their export performance. Exports were desperately needed to bring in revenue to rebuild the war-damaged economy, so the scheme’s rationale was sound and practical. Rover’s problem was that it had no new models ready to put into production. All it could do was go into production with warmed-over pre-war designs as a temporary measure – and these were not going to succeed in export markets where they came up against the latest American designs.

HUE 166, with chassis number R.01, was the first pilot-production Land Rover from 1948, and is now a much valued and still quite active museum piece. It was pictured during the seventieth anniversary of Land Rover as a marque, in 2018.

So there was a desperate need for a new product that would sell well in export markets, and it was Maurice Wilks who came up with the solution. He had bought a war-surplus Jeep in 1947, and had quickly come to realize how useful it was as a multipurpose runabout, farm vehicle and even leisure vehicle. The Jeep had created a demand for simple and robust transport wherever it had been seen during the war, and Wilks realized that Rover could build a similar vehicle, using many major components in production for the company’s cars. Aimed at agricultural and light industrial users – and it soon became a military vehicle as well – the Land Rover was designed in record time and was in production by summer 1948.

It was an immediate and massive success, far greater than even its manufacturers had imagined might be possible. All thoughts of it being a short-term temporary product were abandoned, and over the next two decades the Land Rover became the primary product of the Rover Company. There were still elegant and well-engineered Rover cars to remind the company of its origins, but the investment that made them possible came largely from the Land Rover.

THE RANGE ROVER IS BORN

The next important step in the company’s evolution came in 1970. Spen King, a nephew of the Wilks brothers and an innovative engineer at Rover, realized that it would be possible to create a more comfortable Land Rover designed primarily to carry passengers by using the long-travel suspension that he had drawn up for the company’s last new saloon car, the 1963 Rover 2000. Adding all-round disc brakes (again from the 2000), and using the V8 engine that Rover had taken over from General Motors in the USA, would give far better road performance than could be offered by any Land Rover. And so in 1970 the Range Rover was born as a sort of super Land Rover.

Once again, worldwide demand for Rover’s new product outstripped supply by a huge margin, and this time the customers discovered in the new product something much more than a comfortable Land Rover. The Range Rover quickly became a prestige purchase, and although in the early days it was no luxury car, many people considered it as a realistic alternative to one. The obvious course of development was held back for many years because in 1968 Rover had been absorbed into British Leyland, and in the 1970s British Leyland had to devote most of its resources to its ailing volume cars division (formerly Austin and Morris), and could not afford to invest in improvements to a model that was already selling more than Rover could make.

Another first:YVB 153H was the first pilot-production Range Rover to leave the Despatch Department at Solihull (which was a holding area for newly assembled vehicles before they were despatched out to a user or dealer). It was the start of a new direction for the Land Rover marque.

This was the third-generation Range Rover, or L322, which became available as a 2002 model and was in production when the Range Rover Sport was launched. It was a highly sophisticated model, and rather larger than the Sport.

A Sporty Range Rover

Land Rover itself chose to develop the Range Rover as a luxury model, for the simple reason that a luxury 4×4 seemed to be what most of its customers wanted. But within the original concept of the Range Rover there had been the basic concept of a 4×4 with much enhanced road behaviour and exciting performance, and it was those aspects of this multi-sided vehicle that stood out for some buyers.

To meet the expectations of that buyer group, Arthur Silverton established a Range Rover conversions business as an offshoot of the company whose British operations he directed. Schuler Presses (who made machine tools) gave birth to Schuler-branded Range Rovers, which from the mid-1970s incorporated a whole range of enhancements. There were higher-performance engines, quieter transmissions that included automatic options (not available on the original Range Rover), braking and suspension enhancements, and a host of other items that really presaged what the Range Rover Sport would achieve thirty years later.

Overfinch specialized in adding extra performance and handling to the original Range Rover, successfully exploiting the first stirrings of a market that would develop into the customer base for the Range Rover Sport.

Schuler eventually tired of having their name associated with Range Rover, and there was allegedly some embarrassment in connection with their provision of presses used in making the Mercedes-Benz G-Wagen, which at that time was seen as a Range Rover rival. So the Range Rover business was spun off with the new name of Overfinch. In 1985, Overfinch was sold to new owners, who continued offering a wide range of enhancements for the original Range Rover right up to the end of its production in 1996 – and beyond.

Schuler and Overfinch Range Rovers were always expensive, and that ensured their rarity. But there was always a ready demand from wealthy buyers for these high-performance Range Rovers, and in that demand can be seen the origins of what became the target market for the Range Rover Sport.

CREATION OF LAND ROVER LTD

Inevitably, British Leyland’s problems led to a crisis, and at the end of 1974 the car maker had to seek government support to prevent total collapse. The government stepped in with money, and immediately began to investigate ways of returning British Leyland to profit. The Land Rover products had been consistent profit earners, and the important decision was made to turn Land Rover into a standalone business unit, and to manage it separately from the Rover car marque. So in 1978 Land Rover Ltd was created, with a substantial financial investment from the government.

British Leyland’s subsequent unhappy history needs no retelling here, but it is important to remember that it was during the 1980s that the Range Rover was moved resolutely up-market to become a proper luxury car (without losing the off-road abilities that it had inherited from the Land Rover). In this decade, it was largely the success of the Range Rover that persuaded Japanese companies to introduce cheaper equivalents aimed at family buyers, and it was the success of these that led Land Rover to introduce the Discovery as a competitor in 1989.

BMW BUYS THE ROVER GROUP

Fast forward now to the 1990s. Land Rover Ltd still belonged to British Leyland (known as the Rover Group since 1986), still had three product lines, and was thriving. The Rover Group as a whole, however, was not. It had passed out of government ownership to British Aerospace in 1988, and that company had somewhat reluctantly agreed to manage it for a period of five years. As soon as those five years were up, BAe scouted around for a buyer, and in 1994 the whole Rover Group was sold to the German car maker BMW.

The Land Rover Discovery was introduced in 1989 and gave Land Rover its third model range. This is the very first production model.

The Freelander became Land Rover’s fourth model range in 1997, giving the company a smaller and less expensive entry-level passenger-carrying model. This is the three-door model; a five-door proved more popular with family buyers.

BMW were good for Land Rover. They improved build quality and supported the company’s plan to introduce a fourth product line, which became the Freelander compact SUV in 1997. By this time, passenger-carrying Land Rovers were being built in far greater numbers than the original commercial models (rebranded Defenders in 1990), and the company’s outlook was gradually changing. It was at this point that ideas for what would eventually become the Range Rover Sport began to surface – although it would be several years before they became reality.

PROJECT HEARTLAND, 1994–1997

Land Rover was already thinking about the model that would replace its hugely successful Discovery by the time BMW took control in 1994. Project Tempest was really a cautious evolution of the original vehicle, and BMW encouraged the Land Rover teams to be more ambitious in their thinking. So although they allowed the Tempest programme to continue, the Germans persuaded Land Rover to start work on a far more radical alternative. This programme was run in parallel with Project Tempest, and the Discovery it was designed to deliver could have replaced Tempest as the second-generation production model if things had turned out differently.

Fundamental to the more radical Discovery concept was input from Wolfgang Reitzle, the BMW advanced engineering chief who had been appointed to run the Rover Group. He pointed out that imported vehicles sold well in the coastal areas of the USA but not so well in the middle of the country. He pushed for the future Discovery to hit Jeep sales in this heartland area of the USA, and so the project acquired its name of Heartland.

There was no doubt that Heartland would have to be bigger than the existing and planned second-generation Discoverys if it was to meet US market expectations, and its seven-seat accommodation would have to be better and more flexible than that of either vehicle. John Hall, who had run the programme to deliver the second-generation Range Rover and had now been appointed to run the Heartland project, remembered that the size of the Heartland vehicle became a key issue as a result. What US customers wanted would seem very big to Europeans, while a European-size vehicle was too small to meet US requirements.

Project Heartland would have delivered a more sophisticated and refined new Discovery. This sketch proposal was produced in 1994.

The L35 and L36

So the compromise solution was to develop two versions, a short-wheelbase five-seater aimed primarily but not exclusively at the European market, and a long-wheelbase seven-seater aimed primarily (but again, not exclusively) at the US market. These two related projects gained the code names of L35 and L36 respectively, using the new project code system that BMW had introduced. The exact size of Heartland was never firmly settled, but George Thomson, who was leading the Design Studio input to the project, remembered that the shorter wheelbase would have been between 2,642 and 2,692mm (104 and 106in), while the longer one would have added 100 to 120mm (some 4 to 5in) to that. A longer rear overhang on the seven-seater would have allowed the spare wheel to be stowed under the floor, while on the five-seater it would have been carried outside.

However, other issues came to bear on the Heartland project. First of all, BMW decided not to go ahead with the major Range Rover facelift that Land Rover had planned for the 1999 model-year, but instead to put additional resources into getting an all-new Range Rover on the market about three years after that. Then there was the fact that BMW themselves were working in an on-off fashion on their own SUV model, which they knew as the E53 project and which would become the BMW X5 when it was released in 1999. As a BMW, it inevitably had a strong dose of sportiness in its make-up. On top of all that, the CB40 (Freelander) project was consuming a lot of money and engineering resources. So in early 1997 Heartland, in its initial L35 and L36 guise, was cancelled, and Land Rover’s original plan to make the Tempest vehicle into the new Discovery was carried forward to production. It became the Discovery Series II in 1998.

THE NEXT STAGE: PROJECTS L50 AND L51

Nevertheless, the work that had gone into Project Heartland was not lost. Some of the thinking that had gone into it was carried through to similar twin projects, known as L50 and L51. These two were again intended to deliver five-seater and seven-seater versions of a new Discovery, but this time the five-seater was not aimed primarily at Europe, but was partly a response to pressure from the USA, where Land Rover North America (LRNA) wanted what was in effect a smaller Discovery with a flat roof – ‘a sort of Discovery Sport’, as Land Rover designer Dave Saddington later explained it: ‘The seven-seater had a clear business case but nobody could nail down any sales volumes for the five-seater. It was going to be first into a new market.’

Using monocoque construction to build two different models was considered to be too complicated and expensive. So the plan quickly gelled around the idea of using a separate chassis – although the load-bearing function could be shared to some extent by the body so that the chassis could be more lightly constructed. An important issue was that L50 and L51 were going to have beam axles, because BMW wanted them to be down-market of their own X5 with its all-independent suspension, and also because beam axles gave better off-road performance, which would be expected of a Land Rover. Once the idea of using a separate chassis was in place, a plan surfaced to use yet another version of this chassis for a new Defender as well – although that would never come to fruition.

These two full-size models are L50 and L51 as they looked in 1999; the five-seat model with the flat roof on the right was intended to be the sportier design for the USA. These are the origins of the Range Rover Sport.

Everything then changed again in summer 2000, when BMW sold Land Rover to Ford. Although L50 and L51 continued to exist for another few months, Land Rover’s new owners lost no time in getting to grips with their latest acquisition and in reviewing Land Rover’s future model plans. And although nobody realized it at the time, in the five-seater Discovery that had been part of the programme lay the spark that would later ignite as the Range Rover Sport.

The Significance of the Sport

The rest of the Range Rover Sport story forms the remaining chapters of this book, but before getting into detail it is instructive to look at what the Sport did for Land Rover.

When the Sport was introduced in 2005, it was Land Rover’s fifth model line. Three of the others (the Range Rover, Discovery and Freelander) were passenger-carrying models; only the Defender was fundamentally a commercial vehicle, but even that was increasingly being bought in Station Wagon form for passenger-carrying duties. So Land Rover’s transition from a maker of utility vehicles to a maker of specialized passenger-carrying types was already well under way.

What the Range Rover Sport did was to tip the balance still further towards passenger carriers. But as Land Rover’s entry into a new and emerging market for what the Americans had branded as performance SUVs (Sport Utility Vehicles), it required some mental adjustment at Solihull. Although there was a worldwide appreciation of the Land Rover marque, this was something new and different. It added sportiness, style and fashion into the traditional Land Rover mix, and it was the job of the marketing and public relations teams to ensure that these new elements blended seamlessly into public expectations, as well as winning over new customers.

By the mid-2000s, the original Land Rover had evolved into the Land Rover Defender, and passenger-carrying Station Wagons, like this one, had become very popular. This was the well-equipped 110 XS Station Wagon, at the top of the range from October 2002.

Other makers had spotted the market for a sporty SUV that could also be used as a family vehicle. This was BMW’s X5, which reached the market in 1999.VAUXFORD/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Aimed at very much the same market was the Porsche Cayenne, which made its appearance in 2002. At the time, many people ridiculed the idea of a sports car manufacturer trying to make an SUV, but they were wrong…OSX/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Their success was unquestionable. Although (as noted earlier) there was some resistance from traditional Land Rover owners who felt that the Sport deviated too far from the Land Rover norm, the model’s success was extraordinarily rapid. Released in 2005, it became Land Rover’s best seller for 2006, and in a distant echo of the original 1948 Land Rover’s story, it went on to exceed the expectations of its manufacturers. Initially envisaged as a fashionable model that would need regular changes to remain fresh, and which might have a limited production life, it actually lasted for eight and a half years. And in that time, it taught Land Rover a great deal about brand values and premium marketing – lessons that the company continues to use to good effect.

CHAPTER TWO

EARLY DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Things moved very quickly once Ford had taken over control of Land Rover in summer 2000. The American company put in their own Steve Ross as Land Rover’s new engineering chief, and by the autumn there were serious discussions about the way forward. Decisions were quickly taken about key issues, and one of them was that the reliance on BMW engines had to end. Future Land Rover engines were to come from Jaguar, who had of course been in the Ford stable for many years already, and from other Ford-owned sources.

What BMW had known as the L50 and L51 projects were still in existence, but not surprisingly the BMW engineer who had been running them was recalled to Munich. Into the breach as caretaker manager stepped John Hall, who was then in charge of Advanced Vehicle Design. Hall inherited a project that was becoming stale: there were still multiple unresolved issues about costings, and over in the Design Studio run by Geoff Upex there was a similar sense of staleness. Designer Dave Saddington sensed it keenly, and he felt that the problem lay in the perception of the smaller, five-seat model. So he tried an experiment, positioning one of the full-size L50 models between a Range Rover and an existing production Discovery, and masking off some elements of the design with black tape to suggest a new approach to the five-seater model. ‘I tried to get people to think of it as a baby Range Rover rather than as a Discovery minus,’ he explained some years later.

Geoff Upex ran the Land Rover Design Studio in the first half of the 2000s, and the design ‘language’ used on the models of that period was largely his creation.

THE L319 AND L320 PROJECTS

It was an approach that rapidly gained approval, not only within the design team, but also in the wider company beyond. Thinking of the new vehicle as a baby Range Rover ‘automatically put it into a higher price bracket, so there was no longer any need to bring it down to a price. That made for a better business case!’ So instead of two variants of the Discovery, Ford authorized work on the related L319 and L320 projects. L319 became the Discovery 3 (LR3 in the USA) on its release in 2004, and L320 became the Range Rover Sport when it was released a year later.

There was still no reason why L319 and L320 should not share a common platform, and in fact Ford took the idea one step further. At some time in the future Land Rover would have to develop a replacement for the long-running Defender range, and Ford envisaged that this could have yet another variant or variants of the new platform. An option that seemed to have considerable promise was to use the chassis of the then unreleased new Ford Explorer (model U152) as that new platform. Land Rover’s new engineering chief Steve Ross was probably in favour of the idea, not least because he had led the Ford programme to develop it!

However, neither Ford headquarters at Dearborn nor Steve Ross in Britain had any intention of imposing ideas on the Land Rover engineers willy-nilly. So in September 2000, a group of Land Rover’s chassis and packaging engineers flew out to Ford engineering headquarters in Dearborn for a three-month period in which they were to examine this option in detail. They were headed by Steve Haywood, who had run the engineering teams for the first Land Rover Freelander in the mid-1990s and had then been seconded to a Rover cars project (called R30) that was being run from BMW headquarters in Munich. That project was cancelled when BMW sold Rover Cars, and Steve transferred back to Land Rover.

After some careful debate, the Dearborn study group reached the conclusion that the Explorer’s separate chassis would not be suitable for future Land Rovers. Some years later Steve Haywood remembered:

It was too low to the ground. The approach and departure angles were inadequate, and there was insufficient suspension travel. So it would have needed too much new hardware. We also studied the interior package, and the ‘command driving position’ just wasn’t there. Those two fundamentals were too far from the brand DNA, and the platform was too important for Land Rover’s future. So we convinced management that we needed a new platform.

Ford were understandably keen to use the platform of their latest Explorer, coded U152, for the new generation of Land Rovers – but it quickly became clear that this was not going to work.IFCAR/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

A New Chassis

Steve and his team quickly conceived that new platform as a separate chassis – a conservative approach by comparison with the huge monocoque that BMW had approved for the L322 Range Rover, but considerably cheaper and more flexible. Even so, the new chassis was certainly not going to be a conventional design. Instead, it was to be much lighter than Land Rover chassis of old, and was to carry an ultra-rigid monocoque bodyshell that would bear a proportion of the loads that had traditionally been carried solely by the chassis. When this idea was brought to market with the new Discovery in 2004, it was given the name of ‘integrated body-frame construction’ – partly to explain how it worked, but also undoubtedly to make it sound more exciting than it really was.

During December 2000, the new strategy fell into place. Steve Haywood remembered visiting Dearborn that month to make what Ford call the ‘strategic intent presentation’ to the then outgoing Chairman, Jac Nasser. The next twelve months would see the rest of the engineering and design come together.

Steve Haywood was appointed to run the T5 chassis development team, and later took charge of the L319 project that delivered the Discovery 3.

So the Land Rover engineers now had the job of designing and developing a new lightweight chassis that would suit the L319 Discovery, the L320 baby Range Rover and, longer term, the Defender replacement. This was probably known as L321, a programme number otherwise unaccounted for – although Land Rover have never confirmed this, and the programme never became reality. The new chassis took on another new Ford codename and became T5. Just one important design element survived from Land Rover’s brush with the Explorer: this was the ‘portholes’ in the rear chassis side members, which allowed the driveshafts to run through, rather than under, the chassis rails.

Quite early on in the T5 programme the designers realized that the chassis they wanted could not be manufactured using the traditional die-stamping process. They needed quite complex shapes to get the high stiffness-to-weight ratio that was in the plan, and the only way to achieve these was to use the relatively new process of hydroforming. This used water under high pressure to mould metal into the required shape: the blank metal was placed inside a die of the intended shape, and high-pressure water injected behind the metal to force it into the die. Unfortunately there was as yet no plant in the UK where a hydroformed structure as big as the T5 chassis frame could be manufactured.

This was where association with a huge company such as Ford had its merits. The guarantee of large volumes enabled Ford to persuade GKN in the UK, and what was then the Dana Corporation of the USA, to establish a joint venture to build it. The new company was called Chassis Systems Ltd, and in 2002 work began on its new factory in Telford. This was the Dana Corporation’s first hydroforming business in Europe; production began in 2003, and the T5 chassis frames for the L319 Discovery and L320 baby Range Rover were built there using Dana’s patented Robo Clamp process. An additional advantage of hydroforming was that it was actually less expensive than traditional die-stamping.

The first T5 chassis prototypes did not, of course, have the benefit of being made in the new plant. They were instead built rather more laboriously and by hand, and were ready by summer 2001. Land Rover knew them as ‘Attribute Prototypes’ (a term used for prototypes that incorporate proposed elements of a future vehicle), and some were for L320 while others were for L319. They took to the roads for testing straightaway in the form of ‘mules’, disguised under the bodies of Ford Explorers and Mercury Mountaineers. Although some members of the press realized that they must be test prototypes, it was impossible to tell exactly what was being tested without getting close to the vehicle for a detailed examination – and Land Rover took great care to ensure that could never happen.

Prototypes of the T5 chassis were disguised with the bodies of Ford Explorers and Mercury Mountaineers. This ‘Mountaineer’ was pictured during off-road testing in February 2003.JAN PRINS