7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

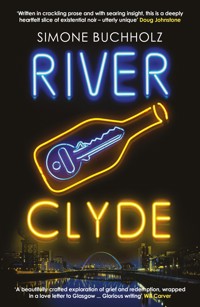

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Hamburg State Prosecutor Chastity Riley travels to Scotland to face the demons of her past, as Hamburg is hit by a major arson attack. Queen of Krimi, Simone Buchholz, returns with the emotive fifth instalment in the electrifying Chastity Riley series … 'A modern classic' Paul Burke, CrimeTime 'Written in crackling prose and with searing insight, this is a deeply heartfelt slice of existential noir – utterly unique' Doug Johnstone 'Deftly captures the beating heart of Glasgow' Herald Scotland 'A beautifully crafted exploration of grief and redemption, wrapped in a love letter to Glasgow … Glorious writing' Will Carver 'Reading Buchholz is like walking on firecrackers … a truly unique voice in crime fiction' Graeme Macrae Burnet –––––––––––– Mired in grief after tragic recent events, state prosecutor Chastity Riley escapes to Scotland, lured to the birthplace of her great-great-grandfather by a mysterious letter suggesting she has inherited a house. In Glasgow, she meets Tom, the ex-lover of Chastity's great aunt, who holds the keys to her own family secrets – painful stories of unexpected cruelty and loss that she's never dared to confront. In Hamburg, Stepanovic and Calabretta investigate a major arson attack, while a group of property investors kicks off an explosion of violence that threatens everyone. As events in these two countries collide, Chastity prepares to face the inevitable, battling the ghosts of her past and the lost souls that could be her future and, perhaps, finally finding redemption for them all. Breathtakingly emotive, River Clyde is an electrifying, poignant and powerful story of damage and hope, and one woman's fight for survival. ––––––––––––— 'In just a few words – a light brushstroke – Simone paints such a vivid picture. Unlike any crime novel I've read. I loved it' Michael J. Malone 'Simone Buchholz writes with real authority and a pungent, noir-ish sense of time and space' Independent Praise for the Chastity Riley series '[A] nerve-racking narrative … [with] a cunning climax that is shocking and deeply romantic' The Times 'Combines nail-biting tension with off-beat humor ... Elmore Leonard fans will be enthralled' Publishers Weekly 'Buchholz doles out delicious black humor ... interwoven in a manner that ramps up the intrigue and tension' Foreword Reviews 'Modern noir, with taut storytelling, a hard-bitten heroine, and underlying melancholy peppered with wry humour' New Zealand Listener 'The coolest character in crime fiction … darkly funny and written with a huge heart' Big Issue 'Fierce enough to stab the heart' Spectator 'A stylish, whip-smart thriller' Herald Scotland 'Combines slick storytelling with substance … like a straight shot of top-shelf liquor: smooth yet fiery, packing a punch with no extraneous ingredients watering things down' Mystery Scene 'With brief, pacy chapters and fizzling dialogue, this almost feels like American procedural noir and not a translation' Maxim Jakubowski 'A smart and witty book that shines a probing spotlight on society' CultureFly 'Fans of Brookmyre could do worse than checking out Simone Buchholz, a star of the German crime lit scene who has been deftly translated into English by Rachel Ward' Goethe Institute 'Lyrical and pithy' Sunday Times

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 219

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Mired in grief after tragic recent events, State Prosecutor Chastity Riley escapes to Scotland, lured to the birthplace of her great-great-grandfather by a mysterious letter suggesting she has inherited a house.

In Glasgow, she meets Tom, the ex-lover of Chastity’s great aunt, who holds the keys to her own family secrets – painful stories of unexpected cruelty and loss that she’s never dared to confront.

In Hamburg, Stepanovic and Calabretta investigate a major arson attack, while a group of property investors kicks off an explosion of violence that threatens everyone.

As events in these two countries collide, Chastity prepares to face the inevitable, battling the ghosts of her past and the lost souls that could be her future and, perhaps, finally finding redemption for them all.

Breathtakingly emotive, River Clyde is an electrifying, poignant and powerful story of damage and hope, and one woman’s fight for survival.

RIVER CLYDE

SIMONE BUCHHOLZ

TRANSLATED BY RACHEL WARD

CONTENTS

for Tom

I drive up and down the windin’ highways

Live my life in single episodes

Hope one day I’ll say I did it my way

Somewhere further on up the road

And I’ve tried to settle down

Every now and then

But I am a travelin’ man

I have been around seen many places

But in my head they all just look the same

I remember people and their faces

But I can hardly remember any names

And I’ve tried to settle down

Every now and then

But I am a travelin’ man

And I’ll try it again

Do the very best I can

Though I’ll always be a travelin’ man

Travelin’ Man – Digger Barnes

in a dreadfully respectable dive not far from the Reeperbahn (a back room behind a club on Grosse Freiheit)

The crystal ball shimmers in every shade of blue from lilac to turquoise, the colours wallow and swim and blend into one another, it’s a prettily arranged LSD accessory and, although there’s no doubt that all this shit is only happening because the ball has a wire and the wire has a plug, and the plug’s plugged into a sodding socket, the witch is still making assertions.

‘Oh, I see money. Lots of money. It’s dropping into your hands – no, I see you boys falling into money. You’ll be positively swimming in banknotes. THAT’s what I see.’

Lightning flickers on the men’s faces, greed is dripping from their eyes. They’re wearing jeans with awkward contrast seams, overly bright, the jeans are the leisure equivalent of expensive suit trousers, they’ve rolled up their shirtsleeves, unbuttoned their collars not a centimetre further than necessary, their jackets are hanging on the chairbacks. It’s hot in the dubious backroom of the outwardly respectable dive, which might have something to do with the kettle barbecue standing in the corner, burning away the whole time. The witch feels the cold.

To get to the witch, the men had to go through the backyard and past the permanently overflowing dustbins, they had to push the mess aside with their highly polished shoes, but they’re used to pushing mess aside. They consider it part of their job.

‘The wealth will just come to you, like clockwork, yes, yes, I see that very clearly, just so long as you don’t go and shoot each other in the face, now that would be silly.’

The men nod.

Of course that would be silly.

Nobody has any intention of shooting anybody in the face.

‘Ha-ha,’ says one of them, he has the largest face, exaggerated by his receding hairline. The others are still doing kind of OK, at least in hairstyle terms.

The witch has aubergine-coloured hair, piled up on her head in an aggressive, wild knot, which could tumble down at any moment. Her eyes are dark-edged, on a grand scale, an eyeshadow massacre, her lips quiver a bright red. She’s small, she’s parked her superhumanly heavy breasts on the tabletop. She’s a kind of a round rectangle, if there even is such a thing.

‘OK, boys,’ she says, ‘so that’ll be two hundred and fifty euros. Can I help you with anything else?’

She knows there is. Usually the people who really want to know something about their future are women. Men are more likely to come to her about guns or sex with teenagers.

‘Well, yeah,’ says the one with the big face. ‘We could do with a little more of your fire accelerant.’

She smiles.

Aha. It’s about a fire.

It’s usually about fire.

‘Why didn’t you say so at the start, you pussies? How much do you want?’

The smallest of them, but not the one with the smallest face, lays thirty thousand euros on the table and says: ‘Five hundred litres.’

She helps herself to a batch of notes, it comes to a grand.

‘OK, come back tomorrow night and park the van right behind the building. You’ll pay the rest on collection. After all, this is a respectable business.’

Now everyone laughs, because a respectable business is something else entirely.

ENTROPY I

Light falls onto my face in splinters, the rhododendron flowers lie on their leaves like heavily laden ships, I lie as mindlessly as I can beneath them. The wind is so slight that you can barely feel it, and it seems to have been made in the rainforest. A damp, warm breath, a delicate soundtrack, a whisper.

But kind of beautiful.

Not that beauty is still a category.

It was always the others who were beautiful, beauty was bombed to hell six months ago.

I turn on my side and look at the letter in my hand. I don’t generally open letters anymore. Why would I.

But the return address…

Alistair McBurney, 338 Dumbarton Road, Glasgow.

Interesting.

Not that interesting is still a category.

I tear the thing open and read, the rhododendron comes closer, covers me over, almost buries me, and after a few minutes, while I’m still reading, the flowers grow away from their branches and towards me. They wrap me up, the white flower behind my ear feels the best, although feelings haven’t been a category for a long time now either.

ENTROPY II

‘Is that you, or is it a branch?’

Stepanovic bends aside the rhododendron branches that have grown down all around me, and lies next to me. ‘And when were you planning to eat something, Riley, you look like a stick.’

‘Are you following me, Ivo?’

‘Don’t flatter yourself, this is just my daily check to see if you’re still alive.’

‘We all have to die.’

‘Yes, but not now.’ He holds out a small, white paper bag. ‘Here, I brought you a cheese sandwich.’

I take it and say: ‘That’s kind of you, thanks.’

He knows that I’ll feed it to the squirrels later.

The branches constrict again, embrace us with a firm grip, Stepanovic budges closer, I shove the piece of paper in my hand between our faces.

‘What’s that?’

‘A letter from Glasgow,’ I say.

‘From Glasgow?’

‘Yes.’

‘What does it say?’

‘Here, you read it.’

He lies on his back and puts his arms round me, with his free hand he takes the letter and starts reading. I lay my head on his chest. Lately, we’ve been ending up this way, from time to time.

ENTROPY III

We’re sitting in this bar, very small, very cramped, not far from the park, we’re sitting very close to one another and drinking gin on the rocks, swimming in my glass is a slice of orange, and there are a couple of juniper berries in Stepanovic’s.

Stepanovic has his hand on my knee as he always does at moments like this, resting on his hand is the back of mine, I’m holding on to the letter as tightly as I can, but it keeps threatening to slip through my fingers. One second, I’m making an effort not to let go of it at any cost, the next moment I’m thinking, oh what’s the point, and then it sort of crumbles away on me.

Blasting from the speakers there’s Macy Gray. Wreckage music.

The last year has ripped through me, the letter in my hand undermined me hours ago, softened me, left me open to attack, the music and the gin do the rest. I never stood on particularly solid ground at the best of times.

Stepanovic has been back at work for a week. Calabretta, Schulle, Brückner, Anne Stanislawski and I are still on leave of absence. We’re stuck on an enforced holiday, we’re just trying to keep on bearing the horror of last autumn, just trying to get used to our condition, because it’s not going away. The big bang, up in that hotel bar, the shot followed by an explosion, didn’t just end a hostage situation and blow a panoramic window to smithereens, it also tore our souls to shreds. My idiotic attempts to stick something back together again by mixing concrete inside me, by dragging stones from here to there and stacking them up, are obviously doomed to failure, because stones, concrete, just fill in the gaps. They don’t heal anything. I do it all the same, and watch on as nothing I do changes anything.

Get up.

Look into the sky.

Eat bread and cheese.

See somebody.

Whatever.

The main thing is that the god of concrete does his job, Emotional Stasis High Command. Just don’t fall apart.

But then the drink floods my cells in full spate, tearing down all the makeshift walls I’ve put up. I haven’t drunk any alcohol for six months, maybe because I knew what would happen next: I’d look for intimacy. And intimacy is not the solution. Intimacy is a threat. Intimacy only holds the danger of it happening again. And again and again and again. Intimacy has to stop, once and for all.

Intimacy needs abolishing.

‘Hey,’ says Stepanovic, laying his free hand on my cheek. ‘There you are.’

I look at him.

His face, the knife-sharp creases around his water-grey eyes, his serious eyebrows, his gloomy tiredness, his angular brow, his curved lips, never entirely closed, permanently in motion but in slow motion, as if they’re perpetually waiting for something, for wind, for example, and then there’s his greying stubble, his gruff chin.

‘The gin, huh?’ he says.

‘Oh yes,’ I say, and: ‘I just need to disappear for a moment,’ because I really do need to disappear for a moment, otherwise I’ll go and fall violently in love with my colleague, and that really would be too tacky. Just because a bit of gin is corroding the concrete and I’ve misplaced my brain.

I put the letter on the bar, I find it relaxing to be rid of it, it weighs too much. As I slip off the barstool, Stepanovic says in English: ‘Please, don’t fix your hair.’

‘What?’ I ask.

‘I didn’t say anything,’ he says.

‘Wow,’ I say and see to it that I really do disappear for a moment now, round the corner and through the jackets and coats and umbrellas hanging in the cloakroom and waiting to be picked up again one day. Maybe I should hang myself up there with them.

I look in the mirror.

My hair’s criss-crossing my face and my shoulders and my neck, there are blades of grass and a few leaves in it too. I gather the strands off the nape of my neck and put them up, make a hasty knot in it, then walk back to Stepanovic at the bar.

‘You did something to your hair.’

‘It won’t last long,’ I say. ‘Do we need more gin?’

‘Do you need anything else?’

He puts his hand back on my knee and stares me down to the basement and, because I don’t know how the hell else to fend him off, I take the letter off the bar and hold it in the air.

‘Let’s leave that complicated letter out of things,’ says Stepanovic.

‘Let’s leave that complicated look out of things,’ I say.

‘Without that look, I’ve got nothing left,’ he says.

‘Bullshit,’ I say, put my hand on the back of his neck and let him damn well kiss me.

He kisses my mouth, my cheek, my throat and says: ‘So, Madam Prosecutor.’

‘Yes, yes,’ I say, and push him away. ‘Scotland, mate. Should I go or should I forget it?’

‘I’m not your mate,’ says Stepanovic, ‘as you very well know.’

He reaches for his glass, revolves it in his hand, watching the barkeeper as he does his barkeeper shit.

‘Don’t look at the barkeeper,’ I say, ‘look at me.’

He looks at me.

‘You’re going to book yourself a flight. And by the day after tomorrow at the latest, you’ll be in Glasgow.’

I open my lips for a second, Stepanovic uses the moment to deploy a cigarette into the situation.

‘I don’t smoke anymore,’ I say with the fag in the corner of my mouth.

‘Please,’ he says, ‘one last time, before you piss off.’

‘I’m not pissing off forever, am I?’

‘That’s what you say now, Riley.’

He holds out a lighter to me.

‘No,’ I say and take the cigarette out of my mouth.

‘Shit,’ he says, ‘well at least sleep with me then.’

‘OK,’ I say, pick up my coat, walk to the door and look at him. ‘Are you coming?’

He puts his glass on the bar.

We walk up the street, there’s the park, there’s the wall, Stepanovic helps me, I climb over, he climbs after me, then we’re in. I take his hand, then I want to go back to my rhododendron because I feel safe there, but he says: ‘No. Right here.’

And I stand with my back to the wall and my hands are on the stone, there’s even some moss, his lips are on my collarbone, his beard scratches my skin, his hands are in my face, on my shoulders, under my T-shirt, on my belly, on my bones.

Then my trousers are off, there’s only a vestige of trouser leg round my ankle.

‘Fuck,’ I say.

‘You can say that again,’ he says and lifts me up, he does it the way I like it, and the wall at my back isn’t hard at all, that must be the moss, I wrap my legs around him and hold on tight for balance, this’ll work, ‘this’ll work,’ I tell him and he says ‘oh yes’ and at once he’s with me and exactly where I want him, and we look each other in the eyes, and his expression is lost and brave all at once. So he helps himself to what he can get and ought to have, and the next one’s on me, a round for the house.

We carry on like that half the night, there are way too many clothes lying around all over the place – they’re missing from elsewhere.

In the middle of the darkness, four hours after sunset and four hours before sunrise, we find ourselves under the rhododendron again after all with the flowers growing like mad, it’s ten times worse than this afternoon, but it’s also ten times more beautiful, it’s the first time in ages that the least little thing has been beautiful, my concrete finally softens up, my hands turn to petals, my heart turns to greens.

back in that respectable dive:

‘Here’s the other twenty-nine thousand.’

‘Here’s your five hundred litres, but don’t set fire to the whole city at once.’

‘No chance of that.’

It sounds a little uncertain.

HOPE STREET

By direct flight from Hamburg to Edinburgh. Then by taxi to Glasgow. That was the easiest way. My batteries are running too low for a more complicated version. Besides, I hate travelling by bus, but who doesn’t.

The taxi driver lets me out in the city centre, at Central Station. I hand him eighty pounds through the hole in the plexiglass screen that separates me from him and prevents us from getting closer than absolutely necessary. A sound concept, in my opinion. Then I take my bag by the handles, climb out and stand on the street.

The city’s greyness is vast, it’s everywhere, and even if the outsized station building in stone and steel and glass tends more to the brown and dark green, its core seems to be the same colour as the rest of the street. It’s a dark yet friendly grey.

The street leading away from the station is called Hope Street.

Next to the station there’s an old Grand Hotel with chandeliers, curlicues and a provocatively luxurious entrance. No, I’d rather not sleep here.

At the other end of the turn-of-the-century station, behind a monumental bridge on which golden letters spell out Central Station, a massive but unexcitable business hotel shoots up from the ground.

I walk over and go in.

Hello, do you have a room free?

Yes, on the ninth floor, is that OK?

It’s fine, thank you.

I take the lift up and put my bag down in the room behind the door with the number 928. Outside my window are tenements, chimneys, cranes, grey. The sky hangs full of clouds, the air is saturated with rain, it’s starting to drizzle. Hope Street heads northwards.

No idea how long I stand there looking, time simply passes, dusk is still a way off, but the clouds grow ever thicker, the grey grows ever more solid, drops of water on the window pane.

I glance at my bag.

Unpack?

It shrugs its handles, I shrug my shoulders and think: OK. Then I’ll just have to go out.

It’s actually raining a bit more than I thought, although not more heavily or at all unpleasantly, the drops are fine and almost warm. All the same, I stand under the bridge. As ever, I haven’t brought that many clothes with me, and there’s no need for half of them to immediately get so wet that they’re unusable for the rest of the time. What time was that again?

There’s something up with the bridge.

Something touches me as I stand beneath it like this, with rain falling on either side. As if hundreds and thousands had already stood here like me. People who were sent here or driven out from somewhere else and didn’t have the foggiest what they were meant to do in Glasgow, but well, now they were there, and they just kind of sought shelter under a bridge and waited for the rain to ease. That’s how it seems to me. I stay standing under this steel umbrella for quite a while, maybe half an hour, maybe two hours. It does me good to slip through time, together with all the other souls. At some point, I set off, heading east.

I want to go to the East End, I want to see it.

I don’t know much about this place, only what my father told me in a few moments of gentleness, mostly of an evening after dinner, and before he got going on the drinking, before he started to fade himself out with bourbon. Then he spoke about Eoin Riley, as if he were telling me a fairy tale, but it was no fairy tale. It was my great-great-grandfather, who, at the end of the century before last, got on a ship in Glasgow to seek his fortune in the United States, working in the steelworks of North Carolina. Eoin grew up in the East End, in a small flat in a grey tenement, in a grey slum. I walk through the streets and I wonder whether Eoin was sick of the grey, if that was why he left, but I don’t really think so. The grey alone doesn’t drive anybody out, and if we have even the tiniest thing in common, my great-great-grandfather and me, then I’d bet that it’s not fearing the grey.

It was presumably more the hunger that usually torments people in grey places.

I reckon Eoin Riley was sick of the hunger.

The next steel railway bridge turns up, but it looks like it dropped out of an old children’s book, it’s far too low, hangs cheekily over the street, no idea how any kind of vehicle’s meant to fit through there, if you please. Right next to the bridge there’s a tower with a clock on it, it’s acting very elegant but looks like someone thought it up over afternoon tea, with no meaning or purpose, just for fun. The tower’s whimsicality rubs off on me, and without paying much attention to where I’m really heading, I get lost among the streets, head a bit left, a bit uphill, then take a long curve to the right, kind of broadly heading east. People hurry past me, they’re quick on their feet, they seem to have a special rhythm in their legs, they’re wearing colours, if not striking ones, their faces are friendly, sometimes a little wonky, but nicely wonky, as if the wind and the rain and the nights had played a role in that.

I stop on a corner, outside a shop. I go in, the rain’s got heavier again and now it is getting on my nerves a bit.

OK then, Scottish corner shop.

Let’s see what kind of stuff you can buy here.

Oh, wow, the cigarettes cost over twelve pounds.

Maybe I should start smoking again.

CLYDE

Meanwhile, the river lies there like over a hundred miles of dead man. Dark, asphalt-coloured, he doesn’t move, ignores the life around him or eats it up with his depth, according to the weather, now the drizzle is lying on his surface, not disturbing him in his rest. The river was once the heart of the city, but no friend to the people: here on the river, they were exploited. He was an oppressor, but he couldn’t help it, that’s just the way the world is, he’s one of the greats, and the greats regulate the little people down, what else was he meant to do? He couldn’t just up and flow off.

Now they’ve forgotten him, the way you do just forget an ex-boss, so he lies there waiting for something to change. For something to come. A mighty reckoning perhaps. Something that breaks things open.

But what.

But who.

He feels every shifting relationship, every change, however subtle. He feels it because after all nothing else happens on his banks.

Like: Oh, there’s something.

And very deep down, on the ground of his being, he stirs.

in a sheltered, secluded back courtyard, not far from Innocentia Park, filling up an old water truck that’s been kind of ‘borrowed’ from Hamburg SV football club:

It’s harder work than they expected, although they should really have been expecting that because: five hundred litres are five hundred litres. And you have to be extra careful with a fire accelerant like that, especially among smokers.

‘Hey! You keep spilling the stuff on my shirt, man!’

‘Then take your shirt off.’

THE FIRST ONE TO MOVE IS DEAD

I just kept following the road, the old, tall tenement buildings left and right, with their dummy windows. Now there’s this cemetery on a massive hill. At the entrance there’s a sign, on the sign it says Necropolis. City of the Dead. Someone’s sprayed Beware of the Dead on a brick wall. Maybe, I think, I’ll get on better among the dead than among the living.

The late-afternoon sun tears a hole in the clouds and pours yellow light over statues and gravestones, the stones stretch up to heaven, and so do I, a bit at least, the light casts my shadow on the asphalt, and I look like my head’s covered in briars, but I reckon that makes me fit into the landscape pretty well. Some gravestones here are in a pretty similar state, hairstyle-wise; there’s one, for instance, where the ivy’s broken through the adornments, the moss has eaten its name, and its overall situation is slanting but stable.

Most of the monuments are missing something.

On some it’s only a tip, but others are missing whole sections, there are broken fruit baskets and laurel wreaths, a lot of the gravestones have simply fallen over. Some Lord Somebody, sitting high on a plinth donated by a few of his friends, has a nose missing. The rain, the wind and the weather gnaw away at the stones, nature chips away at everything, she makes her way back bit by bit just as soon as the people are out of the way, she takes over all that shit and opens her own pop-up shop.