28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

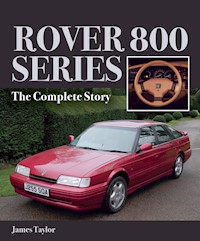

The Rover 800 grew out of a pioneering collaboration between Rover in Britain and Honda in Japan during the 1980s. This book tells the story of how the two companies worked together to produce the Rover 800 and its cousin, the Honda Legend. For those who remember the big front-wheel-driver Rover with affection, this book sets out the full history looking at the design and development of all models: saloons, fastbacks and coupes; the Sterling in North America; comtemporary aftermarket modifications; Police usage and export variants. There is a helpful chapter on buying an owning a Rover 800 and the book is illustrated with 250 colour and black & white photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

ROVER 800 SERIES

The Complete Story

James Taylor

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© James Taylor 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 225 0

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Foreword by John Bacchus

CHAPTER 1 GENESIS

CHAPTER 2 THE FIRST 800 SERIES MODELS, 1986–1988

CHAPTER 3 THE 2.7 AND FASTBACK, 1988–1989

CHAPTER 4 DIESELS AND TURBOS

CHAPTER 5 STERLING: THE NORTH AMERICAN ADVENTURE

CHAPTER 6 THE R17 AND R18 MODELS, 1991–1995

CHAPTER 7 THE 1996–1998 MODELS

CHAPTER 8 AIMING HIGH: THE 800 COUPÉ

CHAPTER 9 800 SPECIALS

CHAPTER 10 BUYING AND OWNING AN 800

Appendix I: Identification Codes for Rover 800s

Appendix II: Rover 800 Production Figures

Appendix III: The 800 Overseas

Appendix IV: The Honda Legend

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Rover 800 was more of a milestone in the car industry than most people realize. It was the largest and most comprehensive joint project ever undertaken by two companies that were not only independent but also geographically and culturally separated by a vast divide. That it was any kind of success is certainly a tribute to the dedication of the engineers at Rover in Britain and at Honda in Japan who worked on it.

Was it a success? On Rover’s side, it provided them with a large car that they badly needed and could not afford to design and manufacture on their own. It taught them new manufacturing disciplines and edged them towards the quality that had been lost during the British Leyland years of the 1970s. That it never sold in quite the anticipated numbers was mostly not the car’s fault – although the bad reputation that British Leyland had attracted still lingered to some extent and must have deterred many buyers. On Honda’s side, it provided them with their first large car and gave them valuable experience of both the European and American large-car markets. The Japanese company has never looked back.

The 800 Series has taken a long time to become an enthusiast’s car, but I was delighted to discover – just as this book was in the final stages of preparation – that it was to have its own formal club. The Rover 800 Owners’ Club was officially launched at the NEC Classic Motor Show in November 2015, and I wish it every success.

In putting this book together, I drew on the vast collection of material in my own archive, amassed since the 800 was new in 1986. I can still remember trying out an 825i demonstrator over the summer of that year, one of the Cxxx AAC registered cars, and being encouraged to see how fast it would go on the M4 motorway. I needed no encouragement, and a nervous salesman suggested that we should keep a sharp look out for police cars when the speedo nudged 115mph. So I backed off. I didn’t buy the car, either, and will admit now that I was never a fan of the early 800. Once the Fastback became available, though, and then the facelifted cars in 1991, my view changed to one of keen interest.

I was pleased to be able to draw to a limited extent on the archives of the British Motor Museum at Gaydon (formerly British Motor Industry Heritage Trust), although surviving records of Rover 800 production are far from complete. I hope that more hard information comes to light in the future. I also drew on the collections and recollections of many others, most of whom may well not even remember passing on vital information all those years ago. Special thanks, though, go to the following: Richard Bryant, long-term friend and long-term enthusiast for Rover cars of all ages (and an 800 Sterling KV 6 owner himself); Paddy Carpenter of the Police Vehicle Enthusiasts’ Club; Sally Eastwood, whose recollection of the end of the US Sterling operation is recorded in Chapter 5; Ian Elliott, formerly involved with PR and marketing at Austin Rover; Tanya Field, who kindly provided her 1991 820 Turbo for photography (she was lucky I gave it back); David Morgan, researcher and great enthusiast for Austin Rover cars; and Ron and Pam Winchester, for the loan of their Japanese-spec Coupé while I was in New Zealand.

James TaylorOxfordshireNovember 2015

FOREWORD

by John Bacchus, formerly Director in charge of the Rover-Honda relationship

In the mid-1970s, I was Strategic Planning Director for BL International. I’d been watching Honda for some time; I found them fascinating because their US performance was astonishing. They had come from nowhere and now a Honda franchise was the absolute prize in the USA. They were also very advanced in their design as compared with their Japanese counterparts.

When Michael Edwardes took over, we quickly realized that collaboration was the way forward. This was unheardof in the industry, at least among the major players, even though it has since become common. A sensible choice at the time looked like an alliance with Chrysler Europe, who were being supported by the government just as we were. Then, before we made an approach, Chrysler was sold to PSA Peugeot-Citroen! Honda was our choice as a replacement collaborator.

Michael Edwardes knew Sir Fred Warner, the former British Ambassador to Tokyo, and he suggested getting him to make the initial approach to Honda. Years later, a senior Honda man told me that this had been a master-stroke: the Honda Board (correctly) assumed an approach through such a man indicated that the plan must have the backing of the British Government!

Just eighteen months into the Honda relationship, we were talking about the joint executive car project. We started out with great optimism, but things became difficult almost straight away. A difficulty was our self-perception. We knew all about executive cars and Honda didn’t, but what we knew was how to build them in the old ‘blacksmith’ way, which was common in Western industry at the time.

Another problem was working out who was responsible for engineering what. We aimed for greater commonality than we achieved, but we wanted to maximize local content for obvious reasons. Then we had problems with our suppliers, because they couldn’t achieve the quality we needed at the prices we were prepared to pay. The tales of woe came up at Board meetings, and I remember Les Wharton saying to me that he couldn’t understand it; what was going wrong? Sadly, I knew I was on safe ground when I told him that every problem component on the 800 and all the quality issues were our responsibility.

It was poor quality that pushed Honda to ask for an end to the original agreement that had us building Hondas at Cowley and them building Rovers in Japan. They were very tactful about it, but there was no way of sweetening the pill. Then it was quality again that was largely responsible for us pulling Sterling out of the USA a few years later.

It was heartbreaking. UK engineering and manufacturing were letting us down. But on the bright side, the collaboration with Honda gave us a very good car which stood us in good stead, and we learned a lot which was applied with great success to the Concerto/R8 programme a few years later.

Wootton Wawen,April 2016

CHAPTER ONE

GENESIS

By the time work began on the Rover 800 project in the early 1980s, the old Rover Company had long since ceased to exist. Since 1975, Rover had simply been one of many traditional British marque names that belonged to the Leyland Cars division of the nationalized British Leyland.

The rot had set in during the mid-1960s. Rover was a small car manufacturer, and as other British manufacturers grouped together for strength, it sought shelter with the Leyland truck and bus group, which already owned Standard-Triumph. From 1968, at government instigation, the Leyland group joined forces with British Motor Holdings, formed in 1966 when Jaguar had merged with the old British Motor Corporation, which owned Austin, Morris and many other marques. The result was the British Leyland Motor Corporation (BLMC).

For a time, BLMC left Rover to its own devices, but by 1971 rationalization was in the air. The Rover and Triumph operations were amalgamated under the Rover-Triumph banner, and not long after that a further reorganization saw them becoming part of BL’s Specialist Division along with Land Rover and Jaguar. In parallel, the less prestigious marques were amalgamated as the Volume Cars Division; in practice, by this time it had been reduced to the three marques of Austin, Morris and MG.

Generally speaking, the buying public remained blissfully unaware, perhaps uninterested, as the once fascinatingly diverse British motor industry was radically slimmed down. It was only when British Leyland ran out of money at the end of 1974 and turned to the government for help that most Britons sat up and took an interest. The reasons for the BL collapse were multiple and are well enough known. When the government stepped in to nationalize the company in order to save jobs, the car manufacturing side was renamed Leyland Cars.

As far as the Rover name was concerned, it still stood for luxury cars, although its original association with top build quality and discreet conservatism had been badly eroded during the 1970s. As Leyland Cars implemented its recovery plan towards the end of that decade, there was no new Rover in the offing because the SD1 saloon (introduced in 1976) was still relatively new. However, from 1979, Jaguar Rover Triumph did begin to look at a project called Bravo, which was a reskinned SD1 with both four-door and five-door derivatives and a range of engines from 2-litre O-series through 2.6-litre straight-six up to the 3.5-litre V8. At that stage, there was no money to look at anything more ambitious.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!