8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

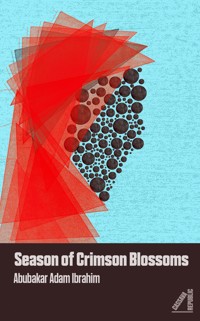

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

An affair between 55-year-old widow Binta Zubairu and 26-year-old weed dealer Reza was bound to provoke condemnation in conservative Northern Nigeria. Brought together in unusual circumstances, Binta and Reza faced a need they could only satisfy in each other. Binta - previously reconciled with God - now yearns for intimacy after the sexual repression of her marriage, the pain of losing her first son and the privations of widowhood. Meanwhile, Reza's heart lies empty and waiting to be filled due to the absence of a mother. The situation comes to a head when Binta's wealthy son confronts Reza, with disastrous consequences. This story of love and longing - set against undercurrents of political violence - unfurls gently, revealing layers of emotion that defy age, class and religion. "A powerful and compelling debut. The taboo subject of an older woman's sexuality, portrayed with courage, skill and delicacy, is explored in the context of the criminal underworld and the corrupt politi that exploits it. This is a novel to be savoured."- Zoë Wicomb, Chair of Judges, Caine Prize for African Writing

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Season of Crimson Blossoms

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim

For Beloved Jos, tainted eternally by the gore of our innocence and memories of the innocents slain

Contents

PART ONE

The Second Birth of Hajiya Binta Zubairu (1956 - 2011, and beyond)

1

No matter how far up a stone is thrown, it will certainly fall back to earth

Hajiya Binta Zubairu was finally born at fifty-five when a dark-lipped rogue with short, spiky hair, like a field of minuscule anthills, scaled her fence and landed, boots and all, in the puddle that was her heart. She had woken up that morning assailed by the pungent smell of roaches and sensed that something inauspicious was about to happen. It was the same feeling she had had that day, long ago, when her father had stormed in to announce that she was going to be married off to a stranger. Or the day that stranger, Zubairu, her husband for many years, had been so brazenly consumed by communal ire when he was set upon by a mob of intoxicated zealots. Or the day her first son, Yaro, who had the docile face and demure disposition of her mother, was shot dead by the police. Or even the day Hureira, her intemperate daughter, had returned, crying that she had been divorced by her good-for-nothing husband.

So Binta woke up and, provoked by the obnoxious smell, engaged in the task of sweeping and scrubbing. She fetched a torch from the nightstand and flashed the light into every corner and crevice. But deep down she knew the hunt, as all others before it, would end in futility.

It must have been the noise of her shifting the wardrobe that drew her niece Fa’iza, who, dressed in her white and purple school uniform, lips coated in grey lipstick, came and leaned on the doorjamb of Binta’s bedroom with the distracted air typical of teenagers.

‘Hajiya, what are you looking for?’

Binta, now busy rifling through the contents of her bedside drawer, straightened with difficulty. She pressed her hands into the base of her aching back and shrugged. ‘Cockroaches. I can smell them.’

Fa’iza made a face. ‘You won’t find any.’

Binta looked at the girl’s face and her eyes widened. ‘What kind of school allows girls to wear make-up as if they are going to a disco?’

Fa’iza had turned and started walking away when Binta called her back.

‘Come, wipe off that silly lipstick. It makes you look ill. And your uniform is too tight around the hips. You should be ashamed wearing it so tight.’

‘Ashamed? But Hajiya, this is the fashion now. You are so old school, wallahi, you don’t know anything about fashion anymore.’ Fa’iza pouted and wiped her lips with a handkerchief.

‘You better put on the bigger hijab to cover yourself up or else you aren’t leaving this house.’

Fa’iza grumbled and, as if standing in a pool of fire ants, stamped her feet in turns.

‘The way you girls go strutting about all over the place these days, the angels up in heaven will have a busy day cursing. Looking at you, who would think you are just fifteen, going about tempting people like that. Fear Allah, you insolent child!’

Fa’iza went off to her room and Binta, determined to ensure compliance, came out to the living room to await her.

Little Ummi was sitting on the couch stuffing herself with bread and tea.

‘Ina kwana, Hajiya?’ She smiled up at Binta.

Binta moved to her and brushed away the crumbs that had collected on the girl’s uniform. ‘And how is my favourite grandchild this morning?’

‘Fine, Hajiya. Do you know what Fa’iza did when she woke up this morning?’ Ummi smacked her lips in a way that always made her grandmother think she was too smart for an eight-year-old.

‘No, what did she do?’

Ummi sidled up to Binta and whispered into her ear. Binta missed most of it but smiled nonetheless. Ummi sat back down and beamed.

Fa’iza emerged from her room pouting, her slender frame covered in the hijab whose fringes danced about her knees, her books swept into the crook of her arm. She pulled Ummi by the arm, barely leaving the child time to pick up her bag.

‘Won’t you have breakfast first?’ Binta put her hands on her hips and regarded the girls.

‘Later.’ Fa’iza was already stamping out with Ummi in tow.

Binta shouted her goodbyes. And because the stench of roaches had faded from her mind, she wondered what she had been up to before the interruption.

She went back to her room and sat on the lush blue tasselled prayer rug. And just as she had been doing since she received the news two weeks ago that her childhood friend and namesake Bintalo had keeled over and died of heart failure, she spent time counting her prayer beads and sending off solemn petitions for friends and kin lost. She prayed for a full life and asked God to receive her with open arms when her time came. However, in the midst of this communion with divinity, the meddlesome Shaytan prodded her with reminders about Kandiya’s unfinished dress lying on her sewing machine. Binta had promised to complete it later in the day. She also had to go to the madrasa, where women were taught matters of faith.

After a quick shower, Binta rushed down her breakfast. Then she retrieved her reading glasses from the nightstand where she had placed them the night before, atop the English translation of Az Zahabi’s The Major Sins.

She oiled and cleaned the sewing machine stationed in the alcove where the dining table, if she had had one, would have been. Picking up Kandiya’s wax print blotched with nondescript floral designs, Binta pedalled away. The task strained her muscles. And her backache grew worse as she was fixing one of the sleeves. It was almost time for the madrasa anyway, so Binta put on her hijab, hoisted her shoulder bag, locked up the house and left.

Ustaz Nura, the bearded teacher, had called in sick and the women were left to their own devices that day. They agreed to make good use of the time by revising previous lessons, but disagreed on whether to start with Hadith, Tarikh or Fiqh. Binta sat through the deliberations, her books piled before her, watching the women over the rim of her reading glasses. After a lengthy and discordant debate, garnished with thinly coated sarcasm, the women left in groups. Binta found herself tagging along with a number of aged women. They chatted about the symptoms of impending senility, the inanities of their grandchildren and how much better things had been in their youth. Until each one made the turn to her own house.

Binta pushed open her gate. She crossed the austere yard where, after dawn, little finches, itinerant pigeons and other birds hopped, pecking the grains and crumbs she occasionally cast for them. On reaching the front door, she discovered, much to her surprise, that it was ajar.

‘Subhanallahi!’ It then occurred to Binta that Fa’iza might have returned early from school. So, driven by a mild irritation over her niece’s escalating eccentricity, she pushed open the door and went in.

A strong arm clasped her from behind, pressing firmly across her mouth. ‘Understand, if you scream, I’ll cut you, wallahi.’ It was a grating male voice. Even though whispered, it almost made her heart, devastated already by the ravages of age and the many tragedies she had endured in her life, burst. The point of a dagger pressed lightly into her throat. She discerned the pungent smell of marijuana coming off her assailant. And with that offending smell came gusts of memories eddying in little swirls around her mind. She struggled and moaned in fright.

‘Money, gold.’ His grip around her tightened. When she nodded, his left arm tightened around her chest while his knife, clasped in his right hand, dug into her flesh, drawing a little pool of blood.

He allowed her to catch her breath. And because she could not see her decoder and DVD player in their places on the stand, she assumed they were already in the khaki-coloured duffel bag on the coffee table. Obviously he wanted things he could take away with ease.

‘Please, I’m old, saurayi.’ She knew from his voice and strong arms that he was a young man. ‘I only want to make peace with my God before my time. Please, don’t kill me.’

‘Money, handset, gold.’ His voice rattled her ear, her heart.

She made to move but he held her tighter. His arm crushed her breasts. She realised, even in the muted terror of the moment, that this was the closest she had been to any man since her husband’s death ten years before.

‘Subhanallahi! Subhanallahi!’ She hoped her muttered appeal to God’s purity would cleanse her mind. Beneath her breath, she damned the accursed Shaytan who persistently sowed such impious thoughts in the hearts of men.

‘Handset!’

She indicated her bag under the folds of her hijab and he allowed her reach for it.

But, having learnt to be suspicious, her assailant speculated that she might be trying something. Like the woman who had sprayed perfume into his eyes in his early days. So he grabbed Binta’s hijab and tried to pull it over her head. She resisted. In the brief and unorthodox tussle that followed, her reading glasses fell from the bag and were crushed underfoot.

‘I’ll cut you, I swear.’

And she knew he meant it. She allowed him to pull off the hijab and seize her bag, the contents of which he emptied onto the floor. He rummaged through the pockets and found a small roll of money. He picked up her handset from amongst the books in the bag and shoved both, money and device, into his pocket.

He straightened. ‘Gold.’

She took the opportunity to look at him for the first time. He was in his mid-twenties, his lips were dark, and his short, kinky hair was like a field of little anthills. He rushed at Binta and held her, positioning himself behind her once again.

Holding her, his dagger at the ready, he guided her to the bedroom. His breath on her neck and the heat from his body made her knees weak. She almost buckled several times. He clasped her firmly so that they tottered like an unwieldy four-legged beast. The friction of her rear against his jeans made his crotch bulge and push hard against her.

In the bedroom, he released her so she could function unencumbered. She leaned over the trunk by the side of her bed to fetch the jewellery, presenting her full backside to him. When she turned, holding a casket of her valuables, he saw that she was not that old. Perhaps a little heavy around the hips, a little heavy at the bosom. Not too mamarish. And when he caught sight of the gold tooth in her gaping mouth, his countenance dimmed further.

She watched him come towards her. ‘Haba! My son, I am old enough to be your mother. Please.’

When he stopped, Binta could not discern the expression on his face.

‘You don’t know a thing about my mother.’

She was perplexed when he put away his knife under his shirt and held up his hands. She held her breath as he fetched a handkerchief from the pocket of his jeans.

‘You are bleeding.’ He reached out and dabbed at her neck, at the spot his dagger had dug into. He looked at the cut and dabbed some more. ‘It’s not deep, you understand?’

Her bosom rose and fell just an inch from his chest. Her breath staggered as he looked into her eyes.

‘I will leave now, ok?’ He stepped back from her. ‘I didn’t mean for this to happen. I just … just …’ He turned and walked out of the bedroom.

He took her things and left, having sown in her the seed of awakening that would eventually sprout into a corpse flower, the stench of which would resonate far beyond her imagining.

The mystery of the missing appliances and Binta’s smashed reading glasses would baffle her daughter Hadiza. Quite unaware of the robbery the previous day, Hadiza had arrived from Kano to pay her mother a visit.

Ummi had jumped on her aunt, who had been trying to set down her bag in the corner of the living room. ‘Aunty Hadiza, thieves came to our house yesterday.’

‘Inna lillahi wa inna ilaihi raji’un!’ Hadiza shrugged off the girl and straightened. She turned to her mother who smiled wanly and waved her hands before her face. ‘Hajiya, what happened?’

‘What happened?’ Fa’iza had just emerged from her room. ‘What happened was that we went out to school and they came and broke the lock and took away the DVD, the decoder and … I don’t know, stuff.’

Binta scowled at the girls. ‘Is that any way to welcome a traveller, you? These girls!’

And so with measured excitement and subtle evasion, Hadiza had been received into her mother’s house.

But later that day Hadiza sat on the edge of Binta’s bed flipping through Az Zahabi’s The Major Sins, astounded by the chance discovery of a well of knowledge in the Sahara. She nodded every now and then and made clucking noises at the back of her throat.

‘I had no idea there were so many mortal sins, Mother.’

When she got no response, she looked up from the book.

Hajiya Binta was still seated on her prayer rug beside the bed, where she had said her Maghrib prayers minutes before. Her lemon-yellow hijab covered her entire body, its hem gathered away from the Qur’an lying next to her foot. She had fetched it earlier to recite after the prayers but Hadiza had invited herself in for a chat. And because her head was turned to the flaxen wall, her daughter could not see her face.

Hadiza turned back to the book and continued browsing through, plucking nuggets planted by the long dead sheikh in a field of papyrus. When she satisfied herself with the limitations of her ignorance, which was far greater than she had assumed, she closed the book and sighed. The intricate oriental design on the spine appealed to her and she ran her fingers over it. She shook her head and wondered what it would feel like to write a book someone would read and marvel at centuries later. Carefully, she put it down on the nightstand. In the process she knocked off her mother’s reading glasses, but caught them as they fell.

‘Mother, how come your glasses are broken?’

Binta shifted beneath the cover of her hijab but said nothing.

‘Hajiya!’

‘Mhm.’

‘I’ve been talking since I came in and you haven’t said a thing.’

‘Don’t mind me. My thoughts were elsewhere. What were you saying?’

‘Your glasses, what happened to them?’

‘They broke.’

‘Yeah? How come?’

‘I ran into a wall.’

Hadiza gaped. ‘How could you run into a wall, Hajiya?’

‘It was dark.’

‘Oh.’ Since she arrived with her little suitcase in tow, greeted more warmly by the mid-morning sun than her mother’s distracted smiles, Hadiza had been dismayed by Binta’s inattentiveness. She felt guilty for not having seen Hajiya Binta for seven months. Since her mother relocated to the fringes of Abuja. Now she wondered if her trip was going to end in disappointment.

At twenty-seven, Hadiza, Binta’s youngest child, was already taking care of a husband and three children; boys who would not stop trashing the living room and shredding their exercise books. For her, any disorder was an excuse to rearrange the interior. So she was always moving the furniture around and planting and uprooting hedges and flowers in every available space in her courtyard. Often, her husband, Salisu, who wore spectacles and spoke with effeminate gestures, would return home to discover that the settee or table had been moved. He had tired of complaining and would simply sit down wherever was convenient.

The last time Binta had seen her, Hadiza, having been seriously vexed by the ban on the wearing of face veils in France, news of which she had ardently monitored, had just acquired the habit of wearing a niqab. Her hands and feet had been tucked away in black gloves and socks. This time though, she came with several jilbabs with sequins down the front and short hijabs that had intricate lace fringes and which stopped at her bosom.

Binta sighed. And Hadiza sighed too. She put down the glasses and turned again to look at her mother, whose face was still turned away. ‘Hajiya, this has nothing to do with the break-in, does it?’

When Binta smiled, the smile disturbed Hadiza more than it reassured her.

‘Of course not.’

‘What happened exactly?’

‘I ran into a wall.’

‘No, I meant with the break-in?’

‘Oh, nothing. Just the small ’yan iska who break in to get something for dope.’

‘I see. So what exactly did they take?’

But Binta was looking at the wall again.

Hadiza leaned forward and observed the lost look in her mother’s eyes, how she seemed to be looking through the walls at some mystery in the nascent night.

When Binta sensed Hadiza prying into her face, she turned her back to her. ‘Do you think of him sometimes?’

‘Who? Father?’

‘Your brother.’

‘Munkaila?’

Binta was silent awhile. ‘The other one.’

Hadiza’s eyes widened. ‘Yaro?’

‘Sometimes I wonder what he would have become had he lived.’ And then Binta allowed silence to swallow her thoughts.

In the silence, Hadiza’s bafflement increased. Were they actually talking about Yaro? It was the first time since his death, fifteen years ago, that she had heard her mother make any reference to him. It had seemed to her, when she thought about him, that they had buried not only his corpse but also his name that was not a name. And memories of him as well. She shifted closer to her mother. ‘Are you all right, Hajiya?’

But then Fa’iza breezed in. ‘Aunty Hadiza—’

‘Don’t call me that. How many times will I tell you to call me Khadija? That is the proper name. Say Aunty Kha-di-ja.’

‘Aunty Khadija? But everyone else calls you Hadiza, and you know, you are not really my aunt, technically.’

‘Lallai, this girl, you have no respect. Is Hadiza not a corrupt version of Khadija? And don’t forget, I’m not your mate, whether I’m your aunt or not. Technically.’

‘Ok, Aunty Khadija.’ Fa’iza sat down on the bed, sweeping her dress under her and posing proficiently with her hands on her lap like a queen holding court, a pose she had adopted from Kannywood home videos, which, along with soyayya novellas, occupied the bulk of her leisure time. She would not admit, not to Hajiya Binta especially, that they had become an obsession. A refuge from the shadows in her head.

Fa’iza had been living with her aunt since her mother, Asabe – Binta’s younger sister – had returned to the village, having lost her husband and only son in the incessant turbulence in Jos. She had been embarrassed, when her mother decided to remarry, by the choice of a stepfather. This sentiment was inspired by her loyalty to her late father’s memory, by the fact that he was gone forever and would have no further need of his wife.

Whatever she found worthy of scorn in the man who now paraded himself as her mother’s husband – his buck teeth and always-dirty feet, and the fact that he was, in the manner of country folks, less refined than her father had been – was born out of these sentiments. Fa’iza would not even visit. How could she possibly live in the village?

But beyond the distraction she craved from the romantic life portrayed in the films and literature of Kano, which was an escape from the haunting memories of Jos, living in the village would make her less appealing to men in the class of Ali Nuhu. Manifestations of her teen infatuation with the film star were evident everywhere in her room in the form of stickers stuck in the corners of her mirror, on her varnished wardrobe, her cream-coloured walls, the door panel and windowpanes and on the covers of her notebooks. Even on the easel she had used for her fine arts practicals, which was now tucked away behind the wardrobe.

Whatever would Ali Nuhu do with a village girl?

Living on the fringes of Abuja, in the sprawling suburb of Mararaba, was not the same as living in the heart of the city. But at least, here, she could nurture her ornate dreams. So she would paint her face, stick up her posters, watch Kannywood films and read soyayya novellas in which handsome men in sedans fell in love with beautiful girls with moon-like eyes and aquiline noses. Women not unlike her cousin Hadiza.

‘I like your henna decoration.’ Fa’iza held Hadiza’s hands and marvelled at the intricate designs so pronounced on her delicate skin. She looked up and saw Hadiza smiling. ‘When I start writing soyayya novels, I’ll put your face on the cover.’

Hadiza laughed. ‘Stupid girl, my jealous husband will kill you and burn all your novels. Who reads those things anyway?’

‘That’s all she reads, this girl.’

They both turned to look at Binta, who had spoken.

But Binta was looking straight ahead. ‘She reads them from morning till night, if she’s not watching films on Africa Magic. I was wondering where she gets them from until I realised the Short Ones supply them.’

‘Kai, Hajiya!’ Fa’iza protested.

‘What Short Ones?’

‘Some short girls she has made her friends. They live nearby.’

‘Sounds like you don’t like them, Hajiya.’

‘Those girls, they are too smart for their own good. I wish Fa’iza would stop associating with them.’

Hadiza frowned. ‘Fa’iza! Behave yourself and keep away from bad friends, mara kunyar yarinya.’

Fa’iza puckered her lips and turned her face away.

‘Anyway, now the decoder is gone, she won’t get to watch all those useless channels.’ Hadiza adjusted her scarf.

‘Useless channels? Haba, Aunty Khadija. Anyway, Alhaji Munkaila will replace what was taken, insha Allah.’

‘Was that what he told you?’ Binta’s voice sounded burdened by the weight of unrelated memory.

‘Me? No.’ Fa’iza was flippant. ‘Well, he brought these ones. Insha Allah, he will replace them.’

Hadiza turned to her mother. ‘Well, has the break-in been reported to the police?’

‘The police?’ Binta chuckled. ‘It has been reported to Allah.’

‘Since when has Allah become a policeman, Hajiya?’

‘He will dispense justice in His own fashion. Even on the police who go about shooting innocent people. Allah will judge them.’

Hadiza flinched at the virulence in Binta’s voice. It must have something to do with this sudden mention of Yaro, this exhumation of disregarded memories. ‘Well, I still think a formal report should have been made. You never know.’

Binta conveniently observed that the muezzin had called for Isha prayers. ‘Go look for your sister, Fa’iza. I’m sure she’s playing next door.’

‘Me?’ Fa’iza shot up, without waiting for an answer, as if she had been sitting on a spring. She threw her veil over her shoulders and walked out, leaving a whiff of thick perfume in her wake. Hadiza savoured it for a while and then waved her hand, with a dismissive carelessness, in front of her face as if to dispel the scent. Her eyes wandered around the room and lingered on the mournful curtains, the heap of unwashed clothes in the corner and the litter on the floor.

Hajiya, I think I’ll help you move your bed and re-arrange the room.’

Swiftly, Binta picked up the Qur’an before her and handed it to Hadiza. She rose and recited the Iqama for her prayer.

Hadiza sighed, replaced the Qur’an on the nightstand, on top of The Major Sins. She gathered her gown about her and left the room.

Hadiza, plagued by pre-slumber agitations, turned over on the mattress. ‘What’s wrong with Hajiya?’

For a while only little Ummi’s soft snores filled the room. Then Fa’iza, who was lying across the room on the mattress she was sharing with Ummi, looked up from the book she had been reading by the flashlight of her phone and sighed. ‘Hajiya? I don’t know.’ She buried her face in the pages once more.

Hadiza turned again. ‘How long has she been like this?’

‘How long? I don’t know, since yesterday, I guess.’

Hadiza sighed. ‘She seems evasive about this break-in, I don’t understand it. And I don’t understand why she is talking about Yaro all of a sudden. She has never talked about him before.’

‘Yaro? Your late brother?’

Hadiza nodded, put her fingers on her forehead and scratched. ‘Her explanation about her broken glasses was just implausible. What happened really?’

‘What happened?’ Fa’iza sighed and put her book down on the rug by the mattress. The cover showed the face of a beautiful woman with large eyes, and Biyayar Aure written in bold across the top. The flashlight from her phone, which she placed on top of the book, expanded and chased the darkness into the corners. Having turned onto her back, she pulled the sheet over her bosom. ‘What happened was that I just came back home from school and saw the front door open and the decoder and DVD player were gone and Hajiya’s glasses were lying on the floor, broken. I took them to her room and met her sitting on the bed like this …’ Fa’iza paused and stiffened to demonstrate. ‘I asked her what had happened and she sighed like this … hmmm … and said a thief broke in.’

When Hadiza said nothing for a long time, Fa’iza rolled onto her side and lay quietly. Little Ummi, too far gone in her sleep, made little noises and farted. They both looked at her. Fa’iza made a face.

Hadiza, too, turned over on her mattress. A house without a man would look like easy pickings for fence-jumping miscreants of the sort that had broken in. Or was it possible that her mother was just lonely? How had she endured a decade without a man?

‘What about the man who is courting her?’

‘That man?’ Fa’iza scoffed. ‘That dirty old man, Mallam Haruna. He has two wives already, wallahi.’

‘Hajiya, too, is old, you know. Does she like him?’

‘Like him? Haba! How could she like him?’

Hadiza said nothing for a while. When Fa’iza started snoring softly, Hadiza called her name and asked her to switch off the light on her phone.

‘Me? No, I don’t want to sleep in the dark.’ Fa’iza mumbled and was soon snoring again.

Hadiza listened to the noises of the night. A cricket in a crevice somewhere struck up a solo. A cat, out in the dark, startled Hadiza with its meowing, which sounded like the cries of a human newborn. It kept on for a while and then there was silence. The hush was suddenly ripped by the racket two cats made fighting in the moonlight. Finally, staggered quietness ensued, punctuated by Fa’iza’s mild snores, which in time grew into agitated moaning.

‘No … No!’ Fa’iza thrashed about, arguing with the shadows in her dreams, and kicked off the sheet. Hadiza, horrified, sat up, torn between bolting and waking the girl. Fa’iza now started whimpering like a beaten dog. Eventually, she curled up into a foetal position. Soon enough, she was almost quiet, her mild wheezing strumming the night like tender fingers on a guitar.

2

A butterfly thinks itself a bird because it can fly

The first time Binta was woken by the ominous smell of roaches was in the harmattan of 1973. She was sixteen or seventeen. She could never be sure of her age because her mother, who had never attended school, kept dates by association, as did most people in Kibiya. Binta gathered, from conversations that did not involve her, that she was born the year the British Queen visited Nigeria.

She had woken up before sunrise that morning, all those years ago, and lit the hurricane lamp. She shook the mattress, drawing protests from her sleeping younger sister, Asabe, who grumbled. Binta picked up the lamp and searched the small confines of the hut, lifting the mats, probing the calabashes and the single kwalla containing their clothing. She found the crumbling moult of a spider in the first, and the remains of a long-horned beetle in the other. She gave up after prodding the major crevices on the wall with a broomstick and finding nothing of interest.

She went out, performed her ablutions and said the Subhi prayer. Then, as she had been doing for years, she joined her taciturn mother in the faint light of the awakening sun. Together they worked in silence sifting pap with a translucent piece of cloth. Her mother, who was Fulani, slim and dignified but bulging in the middle, hardly said a word to her. Binta was her first daughter and, as was customary, she rarely acknowledged or called her by her name lest she be deemed immodest. But each time Binta sneaked a look into her mother’s eyes, she glimpsed, before it was blinked away, a clandestine love she wished she could grasp and savour. She would have given anything to hear the sound of her name on her mother’s lips. Anything.

When the sun was up, she balanced the tray of kamu on her head and went out, her yellow veil tied around her swaying waist, hawking the kamu around the neighbourhood. As soon as she had sold out, she hurried home, washed, ate a breakfast of kunun tsamiya and kosai and hurried off to school, her school bag – a cut out sack with a shoulder strap attached – swinging as she went.

She walked by Balaraba’s house and met her friend waiting at the entrance. Together, they moved on to Hajjo’s and then Saliha’s. Saliha had not yet returned from hawking bean cakes so they moved on to Bintalo’s.

School was no more than a couple of raffia mats spread out under the ancient tamarind, on which a black board leaned. Mallam Na’abba, the schoolteacher, had often told Binta that she was smart. That she could, if her father consented, continue schooling and perhaps some day become a health inspector. Each time he said that, she would smile and chew on her forefinger, turning her face away from him. It was a far-off dream. She knew that much then. But Mallam Na’abba was passionate about its possibility. It was he who convinced her reluctant father to let her pursue her education for a while longer. That she could benefit the whole of Kibiya with her knowledge. Her father, skeptical as always, had agreed, but carried ridges on his forehead for days afterwards.

After school, the girls went home and met plump Saliha loitering under the moringa tree at the entrance to their house. When she was not hawking, Saliha had inexplicable bouts of headache, backache and a variety of fevers that conspired to keep her away from school most of the time. Her afflictions healed as soon as the prospects of attending class had been eroded. Since she did not seem to be suffering from any of those infirmities at that particular moment, the girls decided to play gada under the barren date tree.

They ran to the field laughing, piling their school bags at the foot of the tree. Because Bintalo was belligerent enough for the entire coterie, they started with her. They formed a semicircle and Bintalo leaned back into their waiting arms. They caught her each time and threw her on to her feet, singing and clapping. Saliha was next and then Binta, who felt the little buds on her chest jiggle each time they threw her, singing:

Karuwa to saci gyale

Ca ca mu cancare

Ta boye a hammata

Ca ca mu cancare

Ta ce kar mu bayyana

Ca ca mu cancare

Mu kuma ’yan bayyana ne

Ca ca mu cancare

Mallam Dauda, who had been standing at the edge of the field, stroking his greying beard and watching the little jiggles on Binta’s chest, asked why they were behaving like tarts. Did they not have things to do at home?

The girls picked up their bags and went home, wondering what business it was of his that they were singing about a prostitute who hid a stolen veil under her arm and were jiggling their little buds. They agreed to meet later that night under the leaning papaya tree to play tashe in the moonlight.

Mallam Dauda went on to have a talk with Binta’s father, Mallam Sani Mai Garma.

Her father returned from the farm that evening with the ridges on his forehead more pronounced than ever, and his limp, caused by his polio-sucked leg, even more obvious. Binta rose from washing the dishes to relieve him of the hoe slung over his shoulder. He brushed her aside and called her mother indoors.

Binta heard him thundering about how big his daughter had grown under his roof and how men now watched her jiggling her melons in public places, and how it was time for her to start a family of her own. He stormed out, kicking his food out of the way. Binta ran into the hut to weep at her mother’s feet. The woman turned her face away to the wall, her hand poised uncertainly over her abdomen.

Two days later, Binta was married off to Zubairu, Mallam Dauda’s son, who was away working with the railway in Jos.

This time, it was the sound of movement in the living room that woke her. She heard wood squeaking on the tiles like some oppressed animal and wondered what was happening. Then she heard Hadiza issuing directives to Fa’iza, who kept echoing each question.

‘Fa’iza, hold that end.’

‘Me? This end?’

‘Move it this way.’

‘This way?

‘Haba! Fa’iza, for God’s sake, what are you doing?’

‘What am I doing? But, Aunty Hadiza, I was only doing what you asked.’

Hajiya Binta, who had gone back to sleep after her early morning prayers, listened to the noises from the living room. She imagined she could feel the weight of her liver, imagined that it felt a little heavier. As she lay in bed, she listened to an unfamiliar birdsong floating in through her window. It was sonorous and confident and if she had not felt weighed down by her body, she would have gone to the window to see the bird.

The sound filled her heart with tranquility and she closed her eyes to savour the sensation. Images of her late husband, Zubairu, the stranger she had spent most of her life with, flitted into her mind. Every time she thought of him, he seemed to be smiling, something he had not been famed for doing so often. Memories of his touch were shrouded in a decade of cobwebs. What she recalled, albeit vaguely, was the sensation of his hands pressing down on her shoulders, his lower lip clamped down by his teeth to suppress his grunts as his body hunched over hers. She remembered how he used to chew his fingers before he told a lie, and how he always slapped his pocket twice before pulling off his kaftan. These memories were vivid. A strong arm around her, crushing her bosom. A strong body behind her. A bulging crotch pressed hard against her rear. Warm, desperate breathing on the back of her neck. A face, young, crowned with spiky hair. Binta realised then that her thighs had been pressed together, that she was moist, down there. Just a hint of it.

‘Subhanalla!’ She shook her head and saw the images dissipate like a reflection on disturbed water. Sitting up, she reached for the Qur’an Hadiza had placed on the nightstand the previous evening. She found that her cracked reading glasses were useless so she put them down. Undeterred, she flipped open the Qur’an and tried to read. The elegant curlicues of the Arabic letters blended into an indiscernible pattern before her eyes. Binta sighed, kissed the Qur’an, replaced it on the nightstand and went out to inspect the commotion in the living room.

Hadiza and Fa’iza were contemplating where best to place the framed painting of a waterfall ornamented with red blossoms that had been on the adjacent wall. Fa’iza held up the frame, while Hadiza, having made up her mind, hammered a nail into the tan-coloured wall.

Ummi stood beside Hadiza with a cardboard box of nails in her hand and a hopeful look in her eyes. ‘Aunty Hadiza, will you bring back our decoder?’

Hadiza, biting down her lower lip, continued to hammer in the nail. Ummi repeated her question and, when nobody said anything, she shook the box of nails. ‘It’s Saturday. I want to watch Cartoon Network.’

Binta stood by the door and observed the transformation of her living room. She thought of it as a minor calamity of sorts. Chairs had been rearranged, the TV stand had been snuggled into a corner and the cornflower-blue vase that had been by its side was now atop the TV. The sewing machine had been moved up against the wall in the dining alcove.

Her greeting, when it eventually came, was mumbled. ‘Sannun ku da aiki.’

They turned to her.

Hadiza contemplated her mother with a scrutiny that bothered the older woman. ‘Hajiya, lafiya ko?’

‘Yes, I’m fine. Why?’

‘You just look … strange, that’s all. Anyway, I didn’t want to wake you. But now that you are awake, I’m going to rearrange your bedroom as soon as I’m through here.’

‘No!’ Binta had not meant to snap. What on earth was wrong with her? She took a deep breath and added in a much softer tone, ‘No rearrangements, please. Just cleaning will do, thank you.’

Realising she was being grouchy, Binta sighed. The images she had woken up with had excited and vexed her more than she would admit. And to think that this moistening of her long-abandoned womanhood had apparently been provoked by someone who reminded her of Yaro was an added irritation.

Hadiza stood, hammer in hand. Ummi picked up a crooked nail from the box and stuck it in her mouth.

Binta made an impatient gesture with her hand. ‘Fa’iza, get me some water. I need to bathe.’

‘Me? Hot water?’

‘Yes, you, God damn it!’

The nail in Ummi’s mouth fell on the tiles and clicked-clicked several times, rattling the sudden silence. Binta turned and went back to her bedroom.

Before Hadiza and the girls could recover from the eruption of Binta’s temper, there was a sound at the gate, succeeded by urgent footsteps crossing the yard. A woman salaamed at the front door and admitted herself.

Fa’iza beamed. ‘Good morning, Kandiya.’

‘Where’s Hajiya?’ The woman’s puffy cheeks quivered. The edge of the khaki green hijab encircling her face was damp with perspiration. It formed a jagged-edged halo around her pudgy face.

Hadiza considered her with interest. ‘Is there a problem?’

Kandiya ranted about how Hajiya had promised to have her dress ready four days before and how nothing had been done about it. She breezed across the room and picked up the dress on the sewing machine. She held up an unattached sleeve between the thumb and forefinger of her other hand.

‘My dress has remained in this state for four days and I’ve paid her in full. I’m supposed to be at a wedding right now wearing it. And because she couldn’t fulfil her promise, she has been avoiding me.’ She observed the dress with considerable disdain and hissed. ‘Iskanci.’ She let the dress, and the unattached sleeve, fall to the ground. Then she stomped out, brushing Fa’iza aside as she went.

When Hadiza went to ask her mother about Kandiya’s dress, she met her huddled on the edge of the bed, her hijab gathered around her, her eyes, before she turned them away to the wall, dark and unfocused.

By the time her son Munkaila arrived, Binta’s mood had improved. She sat in the alcove oiling the Butterfly sewing machine and asked why he had not brought her grandchildren with him.

‘I left them playing with their mother.’ Munkaila, sitting on the couch, hunched forward and jangled his car keys around his finger.

Hadiza, sitting next to him, looked at the keys, at his chubby finger, and saw how it almost filled the key ring. The folds of flesh around his neck and his pot belly, which he patted intermittently, baffled her – things she could not explain as she could his dark skin. That had come from his father’s genes. She could also explain his shortness but not the receding hairline that made him look older than his thirty-four years.

‘I don’t understand how these rascals can break into people’s houses and make off with things.’ Munkaila jangled his keys again.

Binta oiled the shuttle and slipped it into place. She lowered the presser foot and it landed with a thunk. Putting down her feet on the treadle, she felt the machine run. Smoothly. From the huge carton beside her, which had once held a TV set, she picked a piece of cloth, slipped it under the feed dogs, and threaded the needle. She leaned forward to observe the stitches as her foot worked the treadle. But because she wasn’t wearing her glasses, she had to lean further in so that her forehead brushed the machine. She adjusted the tension control and the stitch length and pedalled away until the stitches were no longer oily. She removed the cloth and picked up Kandiya’s unfinished dress.

‘Hajiya, why don’t you use your glasses? Or don’t you like them?’ Munkaila tapped his foot on the floor.

‘Oh, my glasses were broken during … when I ran into a wall.’

‘How come?’

‘It was dark. But I am fine. No need to worry.’

‘I suppose I have to get you another pair then. But you should be more careful, Hajiya, please.’

‘I will be,’ she smiled.

The TV was on but only Ummi seemed mildly interested in it. Soon enough, she drew out a square of bubble wrap, which had been discovered during the rearrangements, and started busting the bubbles.

‘Alhaji, should we go out for a bit?’ Hadiza stood up.

‘Ok.’ Munkaila rose and together they went out into the yard, where he stood observing the house.

It appeared to Hadiza that the smirk on his face had become part of his comportment; he seemed so comfortable wearing it. She adjusted her headscarf. ‘Hajiya is straining her eyes too much, I guess. I was wondering if she could maybe stop this sewing business altogether. I don’t like the way women come here and insult her over unfinished dresses.’

Munkaila sighed. ‘She’s just doing that to keep busy. I take care of her.’ He jingled his keys some more and as if Hadiza did not know the details already, Munkaila recounted how he had rented the house for his mother and relocated her from Jos when he reached the conclusion that the riots and killings would not end; how he had installed satellite TV and paid the monthly subscription so she would be comfortable in old age. ‘What else would she do with her time?’

While he talked, Hadiza wondered if she was the only one who remembered him as the scrawny undergraduate he had once been, with just one pair of jeans and a couple of spandex shirts to last him an entire semester. Those days at Ahmadu Bello University had been tough for him. When Munkaila graduated at twenty-five, with a degree in Economics, and could not find a job, he interned at Harka Bureau de Change. There, he made money buying and selling foreign currencies. He got lucky when he won the trust of some politicians in government who decided to run their foreign currency business through him.

‘Well, she could maybe go back to teaching. There are primary schools around here she could work with. Maybe even part time. She always enjoyed teaching.’

Munkaila’s palm moved up and down his midsection for a while. The image Hadiza’s words conjured in his mind contradicted the one he had of his mother living out her days in contented grace. In the fashion of a queen mother.

‘Look, I don’t want her being subjected to all sorts of … indignities. She should be comfortable now. She shouldn’t suffer all her life.’

‘Hajiya is not that old, you know.’

‘I know, I know. But still—’ He shrugged.

‘I was thinking she could perhaps remarry.’

‘Remarry?! Haba! Hadiza, remarry?’

‘Sure, why not? Her age mates are remarrying all the time.’

Munkaila cocked his head to one side as if to consider the proposition. The prospect had no appeal for him whatsoever.

Hadiza read the expression crystallising on his face as that of a man who had by chance tasted bitterleaf. ‘Listen, I am a woman and I know how important it is to have a man around. Hajiya is lonely. She is open to the idea. She had mentioned before that there was a man here trying to court her.’

‘Ah-ah! Here?’ His mouth dropped in horror. The thought of his mother with another man, other than his father, was shocking enough. He had never imagined anything so horrendous.

‘Don’t worry, I won’t be leaving until tomorrow so I will find time to talk to her about it. Whatever she says, I’ll let you know.’

Munkaila sighed and jiggled his keys some more. He looked down at his shoes and stamped his right foot. Then he looked up at her. ‘Your husband is taking good care of you. Who would have thought you are a mother of three already?’

‘Thank you.’ Hadiza bowed with the grace of a practised thespian. And they both laughed. ‘But all this smooth talking won’t stop me from reminding you that you need to sponsor me to hajj.’

‘In time, Hadiza, in time. My plan was for Hajiya to go first and Alhamdulillah, she went only last year. As for you and that crazy sister of yours, I’m afraid you will have to wait because of the house I’m building. It’s taking all my money, wallahi.’ He went on about how he so desperately wanted to live in his own house and stop paying the exorbitant Abuja rent. About how he wanted Hajiya to move into the quarters he was building for her, how Hadiza needed to see the place to appreciate how much he was spending. And then he invited her to spend some time at his house, since his wife and two daughters had been asking after her. He stopped when Hadiza sighed.

‘What is it?’

‘She mentioned Yaro.’

‘She did?’ Munkaila’s face, dark already, darkened further. Unmindful of his sparkling white kaftan, he leaned back against the wall and held his chin in his hand.

In the grave silence that followed, Hadiza looked around and imagined what colours some hedges and flowers would add to the austere yard that stretched before her eyes like a patch of wasteland, like the last decade of her mother’s life.

The next day, Hadiza threw aside the sheets and rose. She looked at the wall clock and saw that it was already a quarter to eight. Because of her two boys, Kabir and Ishaq, who had to be readied for school, and the little one, Zubair, named after her father, who insisted on having breakfast alongside his brothers, she was unaccustomed to sleeping late into the morning.

From across the room, Fa’iza’s mild snores reached her. Hadiza saw that the girl had kicked away her sheet and her legs were thrown carelessly apart, one resting on little Ummi, who was too busy sleeping to notice.

She got up from the mattress and looked at her face in the mirror that had Ali Nuhu’s face stuck at each corner. She observed the oily sheen of sleep on her face so she used her palms to wipe it off and went out to the kitchen. There, she searched the drawers and cabinets and came up with a pack of noodles. Uninterested, she put it back where she found it. She should ask her mother what they could have for breakfast.

In Binta’s room, she found the clothes that her mother had slept in strewn on the bed. Her mother was having her bath, so she sat on the bed and waited.

When Binta emerged, she smiled at Hadiza and enquired how well she had slept. Hadiza assured her that her night had been pleasant enough.

‘Is that an injury on your neck, Hajiya?’

Binta felt the spot where the rogue’s dagger had punctured her skin. It was no more than a scratch that had hardened into a little black scab, which was peeling off of its own accord. ‘Just a scratch. Have you spoken to your sister?’ Binta sat on the stool before the vanity table and looked at the healing wound in the mirror. In one swift movement, she peeled off the scab and examined the fresh skin.

‘No, not since I arrived. Should I call her?’

‘Perhaps not. Hureira is so much trouble, you should just let her be.’ Binta applied lotion to her body. ‘Her husband called me the other day to complain about her tyranny. I promised to talk to her but she wouldn’t take my calls.’

‘Hureira kenan!’ Hadiza chuckled. ‘She should have been a man with that temper and rebelliousness.’

‘Lallai kam! She would have been worse than your father was, may Allah rest his soul.’

‘Kai! Hajiya.’

‘Well, you know it’s true.’

Hadiza said nothing and after a while she stood up. ‘Well, I was wondering what you wanted for breakfast so we could send Fa’iza to the shops.’

‘How about masa?’ Binta smiled as she powdered her face. ‘Tabawa makes the best masa in these parts. Fa’iza knows her place.’

‘Ok. Masa it is.’