Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

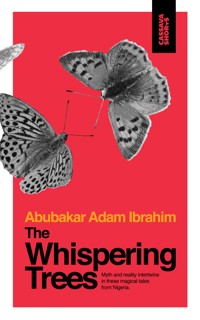

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The magical tales in The Whispering Trees capture the essence of life, death and coincidence in Northern Nigeria. Myth and reality intertwine in stories featuring political agitators, newly-wedded widows, and the tormented whirlwind, Kyakkyawa. The two medicine men of Mazade battle against their egos, an epidemic and an enigmatic witch. And who is Okhiwo, whose arrival is heralded by a pair of little white butterflies?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 203

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

THE WHISPERING TREES

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim

5

To mum and dad; For a life!6

7

“Listen more to things

Than to the words that are said

The water’s voice sings

And the flame cries

And the wind that brings

The wood to sighs

Is the breathing of the dead”

- Birago Diop in Breaths8

Table of Contents

The Garbage Man

‘Shara! Shara! Shara!’

His voice rang out in the mild rain, firm and melodious. It reached her, an echo from a distant dream as she stood on the veranda, absorbing the spray and the melancholy that rain had bred in her.

Zainab had been alone in the house, as always, reading James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans when the rain had come with its overwhelming sense of grief. The image of herself and Fati, her older sister, had come to mind—two little girls in frayed gowns wailing over their dead mother, taken by a failed heart. The rain on the roof had drowned out their cries.

That afternoon, when heaven’s fingers were done drumming on the rooftops, she came out, looking through the dwindling rain at the young flame tree in the middle of the courtyard. It had an almost full head of crimson blossoms now. Some of the blossoms had been washed off and were lying at the foot of the tree.

It was when she was thinking of her grandmother’s sinewy avocado trees that the garbage man’s voice caught her attention. He walked briskly and purposefully. His wet, dark blue work clothes clung to his compact frame. His face was hidden by a baseball cap but he reached out 12and wiped away the rain from his forehead.

Her eyes followed him as he responded to a call from her neighbours’ house. The woman addressed him through the glass panes, pointing to the back of the house. He disappeared behind the apartment and reappeared moments later with a garbage bin. He left the estate then returned with the bin empty. He knocked on the door and collected his fee.

He made a round of the neighbouring houses chanting. Then he turned and left.

Oddly, she woke up the next morning thinking about the garbage man while her husband, Khalid, slept beside her. She got out of bed and went to the bathroom. She flushed the toilet and switched on the heater for Khalid’s bath. Then she went to the kitchen to prepare breakfast. She worked automatically because, beneath, thoughts of the garbage man lingered. She wondered if he had to work in the rain to put food on the table for an ungrateful wife, or to give his little children ‘break money’ so they would leave for school without alerting the neighbours, or to pay rent on the shabby two rooms he probably shared with his wife, two children and his sister-in-law. She giggled. She had no idea if he was married or had two children. She had not even seen his face, so she had no idea how young or old he was. She just thought that while her bespectacled husband worked in a bank’s airconditioned comfort, there were people who worked in the rain and sun. Yet, the garbage man had seemed far from pitiful.

It was not until late in the morning that she realised 13she had been unconsciously waiting for him. She just wanted to see if he could be the man she had imagined that morning, someone with an ungrateful wife, living in squalor with his sister-in-law and two children. She laughed at her naiveté and made for the bedroom. Lying on the soft bed, she quickly fell asleep and dreamt of children playing in the rain.

The next day, her friend, Laraba, who worked as an accountant for a publishing company, stopped by on her way home from work. And as soon as Laraba was seated on the sofa, all Zainab wanted to talk about was her grandmother’s avocado trees.

‘Each season, the trees would blossom and then yield fruits, all but one,’ she said. ‘I kept wondering why until Grandma Talle said it was a male tree.’

‘Why are we talking about avocado trees?’ Laraba asked offhandedly.

‘I’ve just been thinking about them recently,’ she said. After their mother’s death, Zainab and Fati had lived with their grandmother until the old woman had expired five years previously.

Laraba looked at her as if she had left her brains in the cooking pot. ‘Is this what married life has done to you? You sit on your butt all day thinking about your grandma’s trees. I thought Khalid was supposed to get you a job.’

Zainab sighed. Her husband knew people. He had connections. Before their wedding, two months before, he had agreed that she should work, but not with a bank. ‘They are blood suckers,’ he had said. She had a degree 14in public administration and had wanted to work in a bank before she met Khalid. Something about banks and the people who worked in them appealed to her—the smell, fresh and clean, the smart banking halls and how official and purposeful, everyone seemed—things that reflected the sense of order she had always aspired to. It was one of the reasons she had fallen for him. But he quickly made her realise how challenging the work was—’ Especially for a married woman,’ he emphasised.

She told Laraba how Khalid was foot-dragging about getting her a job.

‘So, you sit on your butt waiting for him to get you a job. Can’t you do anything yourself?’ Laraba said.

‘I’m a married woman, Laraba, there are things I am not expected to do, you know.’

‘Yeah, right. I’m not letting any man trample on my rights in the name of marriage.’

The problem with Laraba–and Zainab had been honest enough to tell her this–was that she thought she was too smart.

‘Look, you do go out of your way to prove that you are smarter than everyone else. That can be intimidating, you know, especially for men,’ Zainab said. ‘Yes, they would love to get you into bed to prove they can conquer you but they won’t want to marry a woman who they feel will challenge them.’

‘What do you want me to do, pretend I’m dumb?’

‘All I’m saying is, yes, you are smarter but you don’t have to go out of your way to show others how dumb you think they are.’15

She saw the shadows creep into Laraba’s eyes. They always did when they talked about her men. They had known each other for years. Laraba was a handed-down friend, sort of. When Fati was getting married, she had handed down to her younger sister a lot of her ‘spinster clothes’. Days later, Zainab had realised that Laraba had come with the package. Laraba was actually a year older than Fati and now, at 30, she was five years older than Zainab. When Fati got married, she moved on to a higher level and, because most of her mates were already married, Laraba had settled for Zainab. Now that Zainab was married, their friendship was already withering.

‘Shara! Shara! Shara!’ the chant floated in from outside. Zainab jumped out of her seat.

‘Is anything wrong?’ Laraba asked.

‘No,’ she answered too hastily. Then she took a breath. ‘Let me dispose of my garbage.’

She opened the front door and called the garbage man.

‘Amarya, good day,’ he greeted. Everybody called her ‘the bride’. Very few in the neighbourhood knew her actual name.

He was in his early twenties, she observed, strong with finely cut features, dark skin and a sparkling smile.

‘Good day,’ she said, a little breathless. ‘My … garbage,’ she gestured towards the rear of her building.

He nodded and smiled, but would not look her in the eyes. He went after the rubbish bin. He took a while coming back, carrying other bins from the neighbours who lived behind her building. The way he held the bins made her think of a cat carrying its kittens by the scruffs 16of their necks. He went out of the estate bearing this burden and deposited it in his garbage cart. He returned with the empty bins and stood before her, looking down at his muddied wellington boots. She was confused for a while.

‘Oh! One minute,’ she said and hurried into the house. There were some small denomination notes on the table. She picked one and flashed a smile at Laraba, who smiled back with a dubious light dancing in her eyes.

When she extended the note to the garbage man, he shook his head.

‘It’s a lot more than that, Amarya,’ he said. ‘Your bin was too full.’

She recoiled, then said okay and went back into the house. She smiled again at Laraba, this time a little nervously, as she picked up another note. The garbage man took off his glove and accepted the money, went to the rear, where he returned her bin, then went about his business.

‘I wonder how much a garbage man makes in a day,’ Zainab said absently.

Khalid paused with his fork halfway to his mouth. He had been oblivious to his wife’s faraway look as she had sat opposite him, more preoccupied with shovelling down his late dinner.

She had reckoned that the garbage man made enough to get by unless he was living with an ungrateful wife, two children and a grown-up sister in-law, all in one room. She smiled at herself and shook her head, wondering 17why she always imagined him living in such conditions.

‘What?’ Khalid asked, putting down his fork and unknotting his tie. He pushed his glasses further up his nose. They made him look older than his thirty-four years.

‘Oh, nothing,’ she said hurriedly, as if he had seen that she was thinking about another man. She held up a glass to her lips and looked through the clear water at him. He had already bent his head down and was busy eating again. She thought he had forgotten she was even there. That night, as he struggled to make love to her—or have sex with her, as she would rather think of it—her mind wandered away from the bedroom and Khalid’s grunts. When he was done, he slumped on her naked breasts and promptly started snoring.

At breakfast, she raised the subject of his getting her a job.

‘Zainab, I know what level women can descend to,’ he explained for the umpteenth time. ‘I don’t want you to be like that, arse-slapping with every man who could get you a promotion.’ He picked up his file and left.

It was then that it occurred to her that he no longer called her sweetheart or Zee as he used to when they were dating. It was now Zainab. Zainab–plainly like that, without any embellishment. She sat down and thought hard and realised that the last time he had called her by any pet name was during their first night together.

Zainab decided to visit Fati just to get away from the 18house. When she called Khalid, he asked her not to stay away for too long—as if he would be home in time for dinner, she thought as she put the phone away.

She walked past the wanzami, busy scraping the last strands of hair off the head of a middle-aged man. She walked past the Yoruba woman bent over her sewing machine in a shed with ‘Lady T’ scribbled over the entrance. She walked past the ice cream vendor, poised like an unsettled bird on his bike. She was walking past Ladi’s shed, where men came for koko and kosai, when she spotted him. The garbage man was seated on a bench, bowl in hand. He ate slowly, all the time looking into the contents of his bowl. She stood by the roadside seeing him in clothing other than his usual coverall for the first time. He seemed removed from the chatter of the other men, mostly traders, workmen and artisans.

It wasn’t long before he finished and stepped out. She ducked behind a truck loaded with wares. Her heart was beating rapidly. From behind the truck, she watched him retreat to a corner and light a cigarette. The sight annoyed her. She adjusted her veil and made to leave, thinking she had been stupid to hide like that. She stole one more look at him to be sure he would not see her. He was busy taking long drags on the cigarette and blowing out smooth streams of smoke. He seemed at peace and looked nothing like a harassed man living in squalor.

She watched him finish the cigarette and crush its butt beneath his shoe. He then started walking towards the junction. She noticed the diminished vigour in his stride, different from when she had first seen him in the rain. 19She followed at some distance. He hailed some traders by the roadside as he passed.

‘Master!’ they hailed back.

She heard some children also call him that a few paces down the road. He responded warmly, not halting. When he got to the crossroad, he headed straight down into the flea market, instead of turning left towards the bus stop. She hesitated only a moment before following. He was constantly being hailed by women, traders and children as he passed. He hailed back and kept moving. She kept following, farther into the market, farther away from the bus stop.

The garbage man ducked into a pharmacy. He spent some time buying some medications. She watched him throw a handful into his mouth and follow them down with water. He screwed up his face, shook his head and headed back into the crowded street.

He stood for a moment, shielding his eyes from the sun with his hand. Then he headed back the way he had come. She was standing, waiting for him to pass but he walked up to her and smiled shyly.

She wanted to pretend she was not there, that he had not seen her.

‘Amarya,’ he said.

‘How’s work?’ she asked. That was the only thing that came to her mind.

‘I saw you from Ladi’s shed. I thought you were lost.’

He looked into her eyes and she looked away quickly. She knew he had seen the hankering in them. He was confused because he did not think a woman like her 20could desire a man like him.

‘I’ve got to go,’ she stammered.

‘Yes, yes,’ he fumbled.

Then they both started speaking at the same time. They stopped and stared at each other. Embarrassed, she turned and started walking away. She tripped but managed to keep her balance. She didn’t want to look back because she knew he would still be looking at her.

When she sat down to watch her husband eat late that night, she realised she couldn’t admit she loved him. She had walked into a bank in her final year in the university and had met him behind the counter. He had asked for her number. Now she knew she had fallen in love with the idea of him, the idea of living a comfortable life with a meaningfully employed man. That had been helped by her dream of wanting to work in a bank and the notion that bank employees lived well.

But now she knew that if she had met the garbage man earlier, Khalid wouldn’t have stood a chance. It wasn’t that he was more handsome—he was in fact shorter and had less panache than her husband. It was the way she felt each time she saw him. She had never felt that way with her husband, and she knew she never would.

‘What?’ Khalid asked.

She said nothing.

‘Let’s go to bed,’ he said, pushing back the chair and standing up. He stretched and yawned. When he clambered all over her, she let her mind wander in the lost world of Cooper’s Mohicans. She was Cora Munro and Master, the garbage man, was Uncas, the Indian 21brave who would rescue her from Khalid’s stiff-collar world. She imagined it was him making love to her.

For almost a week, the garbage man did not turn up. Zainab hid herself indoors for the first three days because she did not want him to see the effect he was having on her. But then she started to worry and imagined he was gravely ill. After all, he had been taking some drugs when she last saw him. As the days went by, she agonised over not seeing him and wondered if his ungrateful wife was really taking care of him. It then occurred to her that he might resent her for what he’d seen in her eyes that day. Maybe he had classified her as an unfaithful wife and had written her off. She longed to see him, to explain that she was a faithful wife, that she had been brought up in a decent family, that she was not planning to cheat on her husband, that she was just … just not sure what she felt about him.

He came on the sixth day, when she was standing on the veranda chatting with a neighbour. It was midmorning when she saw him approaching in his work clothes. She was delighted to see him. But she recoiled in shame because she knew he had seen what was in her heart through her eyes. Her neighbour excused herself to get rid of her own waste.

‘Master,’ she said shyly when he was standing before her.

‘Amarya, am I taking away your garbage today?’

‘You haven’t been around for a while. I hope all is well?’ she asked. 22

‘I haven’t been feeling well.’ He was looking down, at a spot between his boots.

‘Oh, how are you feeling now?’

‘Much better, alhamdulillahi.’

They stood awkwardly for a moment.

‘Shara,’ he reminded her.

‘Yes,’ she said.

He went to the backyard to fetch the bin, then went and emptied it in his cart and returned. She handed him his fee. He put his hands behind him and stepped back. She didn’t want him to leave and she didn’t know how to keep him. Questions swirled in her head but she dared not ask them. She desperately wanted to know if he was married.

‘Will you come by tomorrow?’ she asked instead.

‘If you ask me to, Amarya.’

When he left, she walked to the foot of the flame tree. She picked up one of the fallen crimson blossoms and rubbed it between her thumb and forefinger. It felt velvety. She held it against her lips, imagining what the garbage man’s lips would feel like.

Soon after Khalid left the next morning, she went to the kitchen and prepared a special meal of pounded yam and bitter leaf soup. She sliced some fruits and put them in the fridge. By eleven, she was through. She showered, put on makeup and sat down to read the last chapters of The Last of the Mohicans. She looked up at the wall clock almost every five minutes. When the hour hand had crawled a full circle, she threw the book down and went 23to the kitchen. She opened the warmer and checked. Pounded yam was no good served cold, she worried. She returned to the living room and slotted in a movie. Five minutes later, she went and peered through the curtains. There was a bird twittering in the flame tree. She watched it for a while and then drew the curtains. She went over to the kitchen and felt the warmer. When she returned to the living room, she replaced the film in the machine with another one. Eventually, she turned off the machine and went to say her afternoon prayer.

Tears streamed down her face as she recited the Qur’an. ‘Forgive me, Oh, Allah,’ she prayed. ‘Help me triumph over my heart’s desire.’

But by the time she said her asr prayer, two hours later, she knew for certain that she was confused. She hated him for not coming. She hated herself for desiring him. She prayed to God to help her overcome the temptation. She wept.

She was still crying when she heard him outside and hurriedly wiped her tears. She rushed to the door. When she saw him standing there in his work clothes, she knew she did not have the strength to fight her heart. She knew she would probably do something stupid. They stood looking at each other. She wanted to slap him, she wanted to tell him to go to hell and she wanted to hug him.

‘Stop smoking,’ she said instead.

He looked down at his wellingtons. ‘I will, insha Allah,’ he said at last. When he looked up, their eyes met briefly. He must have seen the tears in her eyes. ‘Is everything 24ok, Amarya?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Everything is just fine.’

They stood in awkward silence.

‘You asked me to come?’ he said.

‘Why did you take the whole day?’ she demanded. He looked up, a bit surprised, then quickly looked down again. He explained that he had a little problem with the sanitation task force.

‘They seized my cart. I had to sort them out to release it,’ he said.

‘How could people be so heartless? May Allah curse them!’ she said.

He was taken aback by her passion and shifted on his feet. ‘Well, it happens,’ he said at last.

She went in and got him the fruits encased in a plastic takeaway. ‘I made some pounded yam for you so you could eat and regain your strength but it’s gone cold now,’ she said.

He thanked her and waited. She desperately wanted to ask him if he had a wife.

‘Well, I’ll be going inside now,’ she said, hating herself for saying it.

‘Yes, yes,’ he said and turned to leave. She kept herself from asking him to come back the next day as she watched him walk away.

‘You seem distracted tonight,’ Khalid observed as he slipped into bed beside her. He had been up watching the late news while she tossed on the bed.

‘I’m fine,’ she said.25

He launched into a detailed monologue about the fall in share values, the capital market and how the CEO of the stock market was being probed.

‘The corrupt dragon,’ he hissed. ‘Did you know she even forged her certificates?’

She turned away from him and drew the sheet over her head.

Every other day, the garbage man would come to take away her trash and she would stand on the veranda, watching the blooming flame tree. She waited for him to empty the bin and bring it back, and waited to offer him the fee, which he would turn down, bowing his head and taking a step backward. But he never turned down all the meals she made for him long after he had recovered from his illness.

Each time she saw him, Zainab would feel a lump in her throat that would prevent her from asking him all the questions burning in her heart. She began to fear being with him in those two minutes because she feared she would blurt out how she truly felt. Their hearts did all the talking. Sometimes she would develop anxiety that he might have a really troublesome wife, even though she was increasingly suspecting that he wasn’t married.

She hadn’t felt this way since her teens. Her first love had been a boy in her class in secondary school. He had taught her to laugh again after her mother’s death. He had been her first kiss as well. One morning as they had walked to school, cutting through the field of elephant grass, he had stopped her mid-track and kissed her. She 26had felt a tingling sensation along her spine. She had never felt as alive as she had then. But their love had been short-lived, like the liaison between grass and dew. She had known—everyone had known, that she would soon have outgrown him. He had saved her the trouble when he had left town with his parents after graduation.