Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

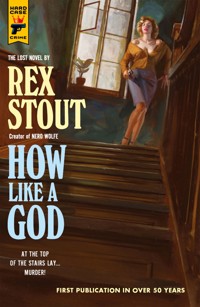

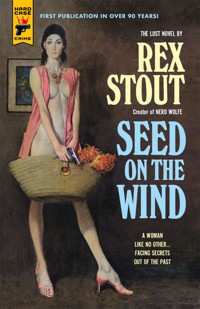

One woman, four men, countless temptations on the streets of New York. This lost novel from legendary "Nero Wolfe" creator Rex Stout—unpublished for more than 90 years—presents a gripping psychological puzzle and a heroine you'll never forget. WHO WAS THE FIFTH MAN? The lawyer, the jeweler, the art critic, and the oil-company man…self-possessed, independent Lora Winter has had a child with each of them. But when one of these men drives up to her house with a fifth man in the car, Lora runs to hide. That's how this extraordinary novel opens – and by the time it ends, you'll have pieced together a masterful psychological jigsaw puzzle that is miles from a traditional crime novel, but whose desperate characters nevertheless resort to kidnapping, blackmail and possibly even murder. Long before he was named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America, before he created the immortal Nero Wolfe, Rex Stout wrote this gripping novel, published in 1930 and then lost for more than 90 years. Hard Case Crime is thrilled to give the book its first publication in nearly a century and to give today's readers the chance to discover one of Stout's richest and most unforgettable stories.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 478

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

Acclaim for the Workof REX STOUT…

“Rex Stout is one of the half-dozen major figures in the development of the American detective novel.”

—RossMacdonald

“Splendid.”

—AgathaChristie

“[Stout] raised detective fiction to the level of art. He gave us genius of at least two kinds, and a strong realist voice that was shot through with hope.”

—WalterMosley

“Those of us who reread Rex Stout do it for…pure joy.”

—LawrenceBlock

“The story has everything that a good detective story should have—mystery, suspense, action—and…the author’s racy narrative style makes it a pleasure to read.”

—NewYork Times

“One of the most prolific and successful American writers of the 20th century…The writing crackles.”

—WashingtonPost

“Practically everything the seasoned addict demands in the way of characters and action.”

—TheNew Yorker

“One of the master creations.”

—JamesM. Cain

“You will forever be hooked on the delightful characters who populate these perfect books.”

—OttoPenzler

“Premier American whodunit writer.”

—Time

“The man can write, that is sure.”

—KirkusReviews

“One of the brightest stars in the detective and mystery galaxy.”

—PhiladelphiaBulletin

“Unfailingly wonderful.”

—SanFrancisco Chronicle

“Dramatic and credible.”

—BostonGlobe

“Rex Stout is as good as they come.”

—NewYork Herald Tribune

“Unbeatable.”

—SaturdayReview of Literature

“What a pleasant surprise for Stout fans…an unexpected treasure from one of the grand masters of mystery.”

—Booklist

At the sound of the door closing behind Martha she suddenly turned over and sat up. The dizziness was all gone. It was all quite clear; it would be the simplest thing in the world. Her father’s loaded revolver was of course in the drawer of the desk in his bedroom, where it had been kept as long as she could remember; as a child she had often opened the drawer a crack and shudderingly peeked at it, not daring to touch it. To get it now, unseen, would be easy, with Martha and her mother both downstairs. Then under her pillow. In the evening he would come to her room as usual, right after dinner. Maybe he wouldn’t. Tomorrow evening then, or the next, or the next; he would come; she could wait. The revolver held six bullets, and all it needed was to pull the trigger. She would wait till he was quite close, the closer the better, even so she could touch him withit…

SOME OTHER HARD CASE CRIME BOOKSYOU WILL ENJOY:

LATER by Stephen King

THE COCKTAIL WAITRESS by James M. Cain

THE TWENTY-YEAR DEATH by Ariel S. Winter

BRAINQUAKE by Samuel Fuller

EASY DEATH by Daniel Boyd

THIEVES FALL OUT by Gore Vidal

SO NUDE, SO DEAD by Ed McBain

THE GIRL WITH THE DEEP BLUE EYES by Lawrence Block

QUARRY by Max Allan Collins

SOHO SINS by Richard Vine

THE KNIFE SLIPPED by Erle Stanley Gardner

SNATCH by Gregory Mcdonald

THE LAST STAND by Mickey Spillane

UNDERSTUDY FOR DEATH by Charles Willeford

A BLOODY BUSINESS by Dylan Struzan

THE TRIUMPH OF THE SPIDER MONKEY by Joyce Carol Oates

BLOOD SUGAR by Daniel Kraus

DOUBLE FEATURE by Donald E. Westlake

ARE SNAKES NECESSARY? by Brian De Palma and Susan Lehman

KILLER, COME BACK TO ME by Ray Bradbury

FIVE DECEMBERS by James Kestrel

THE NEXT TIME I DIE by Jason Starr

LOWDOWN ROAD by Scott Von Doviak

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-161)

First Hard Case Crime edition: November 2023

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London SE1 0UP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

Copyright © 1931 by Rebecca Bradbury, Chris Maroc,and Liz Maroc, renewed 1959

Cover painting copyright © 2023 by Robert McGinnis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Print edition ISBN 978-1-80336-484-1

E-book ISBN 978-1-80336-485-8

Design direction by Max Phillips

www.signalfoundry.com

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

SEED ON THE WIND

I

What startled her was the sight of the green coupé turning into the driveway. Through the window she watched it lurch, down and up, across the ditch at the edge of the sidewalk, then roll smoothly along the gravel, past the forsythia and peonies, to the bare rectangle splotched with oil in front of the little garage at the rear of the house. She frowned; this was Thursday, wasn’t it? Was the man crazy? Manhattan must have exploded into fragments; or—she smiled to herself—was this a wild leap in pursuit of the extension of privileges? She stepped forward to get a better view through the dining-room window, and her amber-grey eyes filled with astonishment as she saw not one man, but two, descend from the coupé. Lewis Kane precisely and efficiently issued from the door on the left, from the driver’s side, while from the other tumbled out a hatless man with a bony white face and a tangled mass of brown hair. Lora’s head shot forward and her neck stretched out for a swift incredulous glance, then instantly she turned and made for the front hall and the door at the other side into the living room.

The three children in the room looked up indifferently as she entered; two small boys, five and seven, from a mountain of apparatus in the far corner, and a girl, a little older but scarcely larger, from the book under her chin as she lay on a long yellow cushion directly before the window. Their involuntary glances were indifferent, through ease of habituation and the absence of any petty chronic filial fear; but something in their mother’s face and her pose, as she stopped in the middle of the room, held their gaze and quickened it; the elder boy got to his feet and the girl turned over and half raised herself.

Lora looked at the girl. “Where’s Roy?”

“He went upstairs to get—”

“All right. Quick! Listen.”

She spoke swiftly, three or four brief sentences, and the girl’s intelligent black eyes answered them as they were spoken. As she ended, “You understand?” Lora had already moved across to the other door, leading to the smaller room in the rear where books and toys were kept, and disappeared through it and closed it behind her before the girl’s nod was finished.

They would come in at the back, through the kitchen, she reflected; Lewis always did; doubtless it was more convenient, with the car parked in the yard, but his face would say plainly, as he entered the dining room through the swinging door, another triumph of prudence. At that rate he must average something like a dozen triumphs a day. But that could wait, time enough for that; it was not with amusement or resentment at Lewis’s psychological costume that she was quivering and standing, drawn tight, close to the door she had shut behind her. That the other man should appear at all was impossible; that after twelve years he should suddenly and unexpectedly emerge from Lewis Kane’s coupé was simply silly. He had been killed in the war; if not that, he had dissolved into some remote and alien atmosphere; at the very least, he had died lingeringly in a distant jungle. But there he was! What about Panther, who had not been trained to lie, except to people she knew? Would this gaunt ghost disconcert her? Poor child, her task would be complicated by the fact that Lewis would inevitably stop in the kitchen to ask Lillian, “Is your mistress in?” An hour earlier Lillian would have been upstairs.…

She heard a low murmur of voices, then footsteps, then from the other side of the door Lewis’s unnaturally loud greeting to the children; even in her suspended expectation of another voice she permitted herself her accustomed smile at his careful loyalty to the theory that children like you in proportion to the amount of noise you make. The other voice was not heard. “How’s my boy?” came Lewis’s booming tones, with the usual unconscious emphasis on the pronoun, and then the sound of Julian’s little feet shuffling dutifully toward the paternal kiss. Then, “Where’s your mother?”

She strained her ears to catch Panther’s reply, but the door was too thick for those low quiet tones. The tone, though, was enough; she smiled at herself for having doubted.

An exclamation from Lewis; then, with a degree of concern remarkable for him, “When will she be back?”

An uneasy thought struck her: what if he decided to telephone; the instrument was in the room where she was standing, on the table not ten feet away. But no, he wouldn’t want the children to hear, nor would he send them off; and suddenly she was grateful to a standard which to her meant nothing, a standard which would also keep him from confronting Panther with a contradiction from the maid. She felt secure as to that, though the tone of Lewis’s questions, punctuated by the quiet murmur of Panther’s voice, sounded more and more irritated and harassed; indeed he almost shouted; at length she heard, “Well, I’ve got to see her tonight. Do you know Mrs. Seaver’s address? Out on Long Island, isn’t it? Funny she didn’t take the car.”

Still the voice of the other man was not heard; perhaps he had remained outside? No, there had plainly been his footsteps. She needed to hear his voice, to make sure, as if the sight of that wild white face and that loose careless body was not enough! After all…the shock of that first glance had made her stupid. Why should she dodge? It was like her to make up her mind and act on it like a flash, only this time her mind had been made up wrong. Her shoulders straightened and her fingers touched the knob of the door—bah, ask him what he wants, maybe he forgot his suspenders—oh, only time is vulgar—but for Panther’s sake the knob did not turn. A moment later Lewis’s goodbyes were heard, and then his retreating steps, accompanied as before; the kitchen door opened and closed, after an interval—poorLillian!—and the sound of the starting and roaring engine came through the window at the rear.

By the watch on her wrist it was ten minutes she waited before opening the door. She passed through. The boys were kneeling in their corner, fastening bits of iron together, not speaking; the girl sat cross-legged, looking straight at the door, her book face-down on the cushion at her side.

“They went right off,” said Panther.

Lora nodded, moving across the room toward the hall door.

“I thought I could hear you breathing,” the girl added.

“That man has legs like a wolf,” exclaimed Morris from the corner, scrambling to his feet.

“He’s my papa,” said little Julian gravely.

“Gee, I don’t mean your papa. Your papa’s ears stick out.”

“Say Lewis,” came from Panther.

Morris grinned. “Aw, well…Lewis’s ears stick out.”

Lora, in the hall, was calling upstairs, “Roy! Oh, Roy!”

After a moment a door opened and closed, deliberately, somewhere above, there were footsteps, and at the head of the stairs appeared a boy, eleven or twelve, with a strong dark face, deep dark eyes, and bushy dark hair. He stood at the top, looking down.

“Yes, Mother?”

“Come down here a minute.”

As they entered the living room Morris was sing-songing, apparently to the mounted globe beside the table:

“Mister Kane, that’s his name, Mister Kane, that’s his name. Julian has to say Papa and I have to say Lewis. His ears stick out right out of his head.” But he stopped as his mother began to speak to Roy, and stood staring at them with an impertinent speculative gaze.

“If the telephone rings you answer it,” said Lora. “No matter who it is, I’m not here, I’m at Mrs. Seaver’s on Long Island to spend the night and you don’t know when I’ll be back. No matter if they’ve telephoned Anne, no matter what they say, that’s all you know.”

Without replying, the boy kept his dark eyes on her face, taking in her words, then suddenly he said, “What if it’s Mrs. Seaver?”

“Say Anne,” Panther corrected.

“Mister Kane, that’s his name,” came softly from Morris.

“It won’t be,” said Lora.

“It might be,” he insisted.

“All right, if it is I’ll talk to her. There was a man I don’t want to see…Panther will tell you…I must ask Lillian.…”

In the kitchen, Lillian, distressed, was also indignant. It was bad enough for Mr. Kane himself to come bursting in through the back door without hauling a stranger in too. And to have been thus finally trapped by him! “Is your mistress in?” She should at least be permitted time to go and make the inquiry and return with an answer, decently and properly, but no, barely pausing on his way to the dining room he would direct the swift question at her with a darting immediacy that brought a “Yes, sir” popping out of her like a cork out of a bottle. Lora had heard all this before; what she wanted to know now was what Mr. Kane had said on his way out. Nothing much, the maid reported; merely that when her mistress returned or telephoned she should be told that Mr. Kane wished to see her without delay.

“I’m sorry I didn’t know, ma’am,” said Lillian.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Lora. She started out, but turned at the door. “That other man, if he comes back tomorrow, either alone, or with Mr. Kane, I’ll see him,” she added.

On her way to the stairs she paused in the dining room to draw the curtains and turn on the light. Outside was the early October dusk, and the brass knob at the end of the curtain-cord was warm from the steam radiator against which it hung. Her hands felt chilly and she closed one of them tightly around the warm knob and then released it again and turned to go. She loathed disquiet, particularly a suspended unreasonable disquiet such as now, unprecedented, filled her breast. With irritation she told herself that she had acted stupidly, but at the same time something within her was saying, oh, no you haven’t, no indeed, you know what you’re doing all right. Ridiculous. She would lie down; no, but she would go to her room and be alone, until dinner. After all, everyone has memories, god help them; given occasion to consider, she would have known that an unexpected sight of Pete Halliday would inevitably arouse an echo of the pain of that old disaster. Damn this silly uneasiness! She should have seen him and let him speak to her.…

As she started up the stairs she heard little Julian’s thin voice from the living room, trying to speak slowly so as to get all the words in: “If you say my papa’s ears stick out your nose will fall off and I’ll walk on it with my iron shoes.”

In her room she sat in the chair by the window, with no light turned on, her back straight and her head upright, her hands folded in her lap.

II

Lewis Kane meant money to her. She sometimes idly wondered, without anxiety, what her life would have been like the past six years but for him. She couldn’t have gone on forever selling the jewelry Max Kadish had given her. That was funny about the life insurance; someone had diddled her, no doubt of that, probably Max’s mother and her lawyer. There was a curious thought for you: Max had meant money to her too, but how differently from Lewis! The money Max gave her wasn’t money, it was merely a handy tool, like the needle and thread she used to sew on his buttons. Whereas with Lewis—ha, that was different, Lewis was the tool himself, poor dear.

Pete Halliday had had no money. Long before. She had worked day after day, nine long hours a day. Nothing disastrous about that, nor even about his leaving; but shift the scene a bit, to another bed, another man, another day.…

Her thought shied off, darted like a frightened hummingbird around the years, and searching for ease settled again on Lewis Kane.

Her first knowledge of him was lost somewhere in the distant past; she had seen him a dozen times, here and there, of no account, before that day six years ago when a telephone call had unexpectedly come from him to the flat on Seventy-first Street. He had given his name, so clearly and precisely that she understood it the first time, unexpected as it was, and without preamble had asked her to dine with him.

“No, I can’t do that.”

“You mean you don’t care to.”

“No, really I can’t. I never go out to dinner. I have three children to put to bed.”

“But surely there is a maid.…”

“Can’t afford one. I never leave them alone except to go to the pawnshop.”

To either the pathos or the humor there might be in that he gave no pause. He said at once:

“I could find a woman somewhere, a trustworthy woman.…”

“No, really I’d rather not.”

A week later he phoned again. In the meantime she had remembered things about him, his calm sensible face, his wealth, his air of assured propriety, and she had given some thought to the probabilities and her present situation. She was not bored, she was far from unhappy, but something was stirring within her. The practical difficulty with which she had put him off did not as a matter of fact exist; she had friends, especially she had Leah, Max’s sister. Indeed, she had too much of Leah, who was orthodox, very short and fat, and talked constantly and disconsolately of her dead brother.

Yes, something was stirring within her. Unhappy or not, she wanted something she didn’t have; that was as definite as she could make it. In Central Park of an afternoon, with Helen (not yet Panther) and the infant Morris both asleep in the carriage, and Roy dodging in and out among the moving trees that were pedestrians’ legs, she would wonder idly which of the passersby were free, entirely free, of the unrest of desire. It would be simple enough, she told herself, if you knew exactly what it was. Say she wanted a new dress, or a home in the country, or a husband. How simple! How simple, probably, no matter what it was. She could think of no object that appeared to be beyond the scope of her powers, nor could she think of any that seemed to be worth their exertion. Did she want—she shifted about on the park bench, she looked in her purse to see if her keys were there, she called Roy to her and straightened his cap and pulled up his stockings—but at length, ignoring the interruptions, the thought completed itself: did she want another baby? Involuntarily she pressed her legs together, tight, and closed her eyes; then opened them again, and watched her hand carefully smoothing out the folds of her soft dark red skirt. Suddenly she smiled. Hardly. Hardly! Three were enough. Indeed, with those three she would soon be wanting something much more modest than a country home, unless something happened. A husband, perhaps. That was not as unthinkable as you might expect, but she would rather not. The perfect husband. Not any.

No. No more babies, thank you.

When Leah came, as usual, in the late afternoon of the day after the second phone call, and Lora asked her if she would stay with the children the following evening, she did not look up, and remained silent, bending over Morris’s crib with her back turned. There must have been something in the tone of the question that startled her. Finally, still without turning, she said with quiet fury:

“You’re going to do it again.”

Lora, setting the table for two, paused with the knives and forks in her hand.

“Do it?”

“Yes, you are.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Yes you do. Tomorrow night you’re not going to any movies with your friends. I won’t come. I won’t ever come again, and God will punish you.”

“I never said I was,” Lora protested. “I’m going to eat dinner properly with a middle-aged man.”

“God will punish you. I told Maxie a hundred times there was a devil in your womb. I told him a hundred times.”

Still she did not turn, and Lora, crossing over and standing behind her, leaned down and put her hands on the other’s fat shoulders and patted them gently. “I know,” she said. “Max told me; he shouldn’t have made fun of you. I don’t mind—perhaps I can get Anne to come.”

At this Leah straightened up, glared at her, and shouted, “If you ask that woman to tend Maxie’s baby I will never come here once more!”

“Well…if you won’t…”

“Don’t be a fool,” said Leah, and bent over the crib again.

The first dinner with Lewis Kane was dull, undistinguished, and interminable. It also appeared to be purposeless. Tall, correct, smoothly strong, a little short of fifty, with a firm discreet mouth and steady grey eyes, he sat and ordered an excellent dinner and with obvious difficulty hunted for something to talk about. Lora, amused, refused to help him. He didn’t matter anyway; she was being admirably warmed by her own fire. There was the mirror on the restaurant wall not ten feet away; and the green dress, though nearly a year old—Max had given it to her soon after Morris was born—was more becoming than ever. Any observer, on a guess, would have subtracted at least three or four years from her twenty-eight, and wouldn’t have guessed the children at all. The mirror showed the fine brown hair, almost red, red in the glancing light, the smooth white skin stretched delicately tight and sure over the cheek’s faint curve and the chin’s rounded promontory, and even the amber threads and dots in the brightness of the large grey eyes. The mirror showed this to her; as for Lewis, he had long ago said correctly, “You are more charming than ever,” and then, to outward appearance, had forgotten all about it. It puzzled her. What did he want? There was no gleam in his eyes, no invitation in his words; he sat and demolished a supreme of guinea hen calmly, leaving a clean bone and no fragments. The observer, invited to guess again, might have hazarded a lawyer with a not too important client or an uncle with a familiar niece, all talked out. After the dessert there were a couple of cigarettes, then an uneventful ride, soft and warm among the cushions of his big town car, back to Seventy-first Street, where he left her at the door.

The puzzle continued for weeks. His invitations became more frequent, always to the same little restaurant not far from Madison Square, and the dinners remained innocuous, never a theatre afterward, always the pleasant digestive ride uptown and the parting at the door. Once or twice he arranged to come early and they drove through the park or along the river for an hour or so with the windows open to the March breezes, he with the collar of his black overcoat buttoned tightly around his scarf, she with her throat open to the swift chill gusts. “He means something deep,” she thought, “or he’d take me to a show or something. Probably he’s going to offer me a job in his office as a filing-clerk; it’s just his thoroughness. Anyway, the dinners are good and Leah loves being left alone with the children.”

He talked correctly and unexcitingly of books, of dogs (Doberman pinschers particularly), of the superiority of Turkish cigarettes, of corruption in politics, of food and music and pictures and English tailors; never of himself or of her. But one evening late in April, as soon as they were seated at their usual corner table and the order had been given, he said suddenly, without warning, without any change of expression:

“You know I’m married.”

Ha, she thought, this is the big moment, he is going to ask me to go to the flea circus. She nodded, laid her gloves on the table, folded her hands under her chin, and watched his face.

“I was married in nineteen-three, twenty years ago,” he went on. “I was twenty-seven, she was a year younger. We have two children: George, sixteen, and Julia, fourteen. They are charming. Two years ago I discovered that I am not their father. Their father is a baritone who sings in a church, and I believe he now also has engagements on the radio.”

He stopped to lean back from the waiter’s arm with the soup, arranged the dish precisely in front of himself, with its edge exactly even with the edge of the table, and picked up his spoon. Lora, saying nothing, poised her own spoon ready for the plunge.

“You probably think I am leading up to a complaint against my wife,” he resumed. “Not at all. Macaulay was wrong when he assailed the common judgment that Charles was an excellent man though an execrable king. Mrs. Kane is an excellent woman, an excellent wife, an excellent mother, but an execrable moralist. She thinks well of her generosity in permitting me to believe that I am the father of two charming and intelligent children.”

He took another spoonful of soup and broke off a piece of bread; Lora, for punctuation, observed:

“She doesn’t know that you know.”

“No.”

“Maybe you don’t.”

“Oh, yes, perfectly. I have the most exact proof; if I had not been blind I should have known long ago. Next month it will be two years since I found out.”

“Well,” said Lora, “maybe it isn’t so bad. And maybe your proof isn’t as perfect as you think it is. It’s a rather hard thing to prove sometimes, there’s only one way really, and since she thinks you have no suspicion.…”

That was putting it delicately, she thought; Pete would probably have said, you never know what you’re getting when you eat hash. But Lewis Kane wasn’t listening; he looked at her in silence a moment and then said:

“I want to be a father, Miss Winter.”

In order not to laugh she bent her head and took a spoon of soup. Ingenuous, direct, the words pleading but all the heart’s yearning crushed precisely to the last drop out of the dull even tone, he went on, “I want to have a son. My wife’s daughter, Julia, was named after my mother. I want to have a son and name him Julian.”

“Well…that should be possible.”

“Yes. You’ve been very patient with me, Miss Winter. No doubt you’ve been dreadfully bored these past two months; I couldn’t help it; I had to make sure you were the sort of person I could trust. You have behaved admirably.”

“I? I’ve eaten your excellent dinners.”

He waved that aside. “I have found nothing that is not extremely creditable. Your conduct since Kadish’s death—I knew him, you know—your general manner of living, your care of your children—by the way, what about Albert Scher? Do you see Scher often?”

This is delightful, thought Lora. What a man! What an incredible man! There was no telling; it might easily prove in the end that all he wanted was a wet nurse or a midwife. She was silent while the waiter removed the soup plates and replaced them with others, but Lewis Kane, not waiting, went on with a faint note of something like apology:

“I’ve missed out on Scher. My reports are very vague about him.”

She suddenly remembered something, and looked at him aghast.

“That man in the brown suit who keeps walking up and down in the park!”

“Perhaps. Does he always wear a brown suit?”

“Great heavens!” said Lora, and began to laugh.

“When I want to find out anything,” said Lewis Kane, “I take the most direct and efficient means at hand. I’m glad you aren’t annoyed.”

“Oh, I’m flattered! Terribly flattered! It would have been so amusing to know he was a detective.—But he seems to have fallen down on Albert. That wasn’t very efficient, was it?”

He frowned and regarded her silently. “Bah, Scher doesn’t matter,” he said finally. “It is apparent, I think, that you are no longer interested in him. But one evening in February, the eleventh, I believe, he went to your apartment and remained till after midnight. I wonder—I would appreciate it if you would tell me what he was there for. Obviously I am not suspicious, or I wouldn’t ask you.”

Lora, almost annoyed, decided to go on with it. “I really am glad you’re not suspicious, Mr. Kane,” she said gravely; and then stopped suddenly at sight of something in the steady grey eyes that was incredibly like a gleam of humor—a swift infinitesimal flash, not believable, like a single distant firefly in a grey evening dusk.

“You think I’m making a fool of myself,” he said. “Not at all. I’ve arrived at a very important decision. I’m attempting to provide every possible safeguard. I’m perfectly satisfied on every point but one. I must ask you again, what is the purpose of Albert Scher’s visits to your apartment?”

She smiled. “Really it’s none of your business, is it?”

“Yes. I think so.”

“Really—”

“Yes. I think it is. Of course, Miss Winter, you are far too intelligent not to know what I’m driving at. Perhaps I’m not going about it properly; with women I have always been—somewhat—at a loss. Certainly it is obvious that what I wish to propose is that you should be the mother of my son. Six months after I learned that I was not George’s father—by the way, he was named after his real paternal grandfather, which was an unnecessary impertinence—I decided that I should have a son. It took me six months more, of careful consideration and elimination, to decide on you, tentatively at least. I was just about ready to consult you when Kadish died, an unexpected complication. In a way I wasn’t sorry, since the delay made possible a more complete inquiry. I waited a year, a full year, surely all that any standard of decency might require.”

That was that, apparently, for he picked up his knife and fork, parted a chop neatly from its bone, cut a triangular morsel from one corner, and conveyed it to his mouth; following it, after a moment, with bread and butter and two swallows of milk. Lora, fascinated, wondered how many days, weeks even, had passed since he had determined to have lamb chops for dinner on this particular Thursday evening. She decided she must say something.

“In the first place, Mr. Kane, I won’t pretend to resent your insult to my womanhood.”

“Yes. Of course. It isn’t necessary.” The second bite of chop went in.

“But to speak of nothing else, the practical difficulties—for instance, it would be hardly possible to guarantee a son—”

“I told you I am not making a fool of myself, Miss Winter.”

“And do you really mean—would you really have made this proposal to me while Max was alive?”

“I am making it to you today, and Scher and Stephen Adams are alive.”

She caught her breath. “That’s rude, and malicious. What do you know of Stephen Adams? How do you even know he’s alive? I don’t.—Besides, it’s illogical.”

“It is,” he admitted. “The analogy is imperfect. But it was plausible to suppose that Kadish’s fate would resemble that of his predecessors. I was willing to wait.”

“I see. Six months to decide on a son, six more to pick out a mother, and a year to investigate her. These last two months—thesedinners—I suppose their purpose was to make me fall in love with you? You were making love to me?”

“Good heavens, no!” His fork wavered in the air, was replaced on the table, then composedly he picked it up again, and resumed, “I selected you for a dozen reasons. You are healthy, and your children are healthy. Your education is sufficient. Your tastes are sound and not extravagant. You are young and handsome. There is no sentimental nonsense in your head. You have lived with three men, been faithful to each, and devoted to none. You never go to church. As for the past two months, there are certain personal inclinations that are discoverable only by intimate and frequent observation. Table manners. Cleanliness. Nervous habits—little nervous habits that escape the ordinary observer. If I thought I could make you love me I might try, though for my present purpose it would probably be inadvisable. My wife has told the father of her children—the letters have been destroyed, but I preserve them in code—that if I were left alone in the world with a million women the race would perish. She is a wit. You must understand one thing, the arrangement between us will be one of complete mutual trust. I do my investigating before, not after. I shall not annoy you. Your income, an adequate one, will begin at once. The details are here.”

Lora, overwhelmed, took the blue folded paper which he drew from his pocket and handed to her; it consisted of four closely typewritten sheets; opening it at random, she saw near the middle of the third page:

17. In the event of an irreconcilable disagreement between A and B regarding education after the tenth year, the person named in paragraph 9 shall be consulted and his decision accepted as final.

She refolded the paper and handed it back to him. Of course, a joke. No, actually, it wasn’t. She felt she must laugh, but she knew it was impossible. Poor man. She could laugh later. Somewhere behind the elaborate ridiculous façade, beneath the thick crust of efficient calculations and crisp phrases, even between the lines of the preposterous typewritten sheets, his harassed soul was squealing and trying to wriggle out of its trap. She could laugh later.

“So you haven’t been making love to me,” she said.

“No.”

“Of course I’m flattered by your list of my virtues. But a little skeptical. It’s too much to expect, even of myself. And I would die of anxiety for fear it might be a girl.”

“Even there your record is good. Two to one”

“True,” she smiled. “But no. I won’t crowd my luck.”

“There’s no hurry. Here.” He placed the paper back on the table beside her plate. “Take that home and read it. Take all the time you want. My mind’s set on this, but there’s no hurry. Let’s talk of something else. Did you see those pictures I spoke of—the moderns at Knoedler’s? If you like the one next to the end on the right as you go in, the red and blue things on a raft or something in the ocean, you can have it.”

He turned and called to the waiter, who hurried over.

“Take these away and bring the salad.”

III

Leah, her bulging form tightly encased in a shiny pink silk dress, the integrity of its seams a desperate tribute to the stubborn heroism of thread, sat in a straight-backed chair by the dining-room window looking vaguely down into the summer lethargy of Seventy-first Street. Suddenly, for the twentieth time within an hour, imagining she heard a noise from the next room, she went to the door and softly opened it, fastened her black Asiatic eyes on Morris sound asleep in his crib, closed the door again and returned to her chair. She was furiously angry. On Sunday afternoons she was permitted—“permitted, my God” —to take the baby, alone, into the park. Outside was July sunshine and a pleasant breeze, not at all hot; and merely because that fool of a doctor didn’t like the baby’s breathing here she was, helpless, sitting in a chair listening to that stupid man with yellow hair talking to that little baby girl—well—he was a bigger fool than the doctor. There was nothing wrong with Morris anyway; tomorrow she would come back and take him out into the sun, and let them try to stop her!

“Here’s another one with a donkey,” the man with yellow hair was saying. “Look, Helen. See the way his tail hangs down. See the lines of the branches on the cypress trees, they hang down the same way. That’s pretty nice. Don’t you think that’s a nice one?”

He was seated across the room near the large table, with Helen on his knee and a portfolio of lithographs propped up so she could see. Five-year-old Roy, silent and looking a little bored, stood at his other side.

“What do the words say?” demanded the girl.

The man frowned. “There aren’t any. Look, can’t you see? There aren’t any words. Pictures are one thing, and words are another thing; I’ve told you that a hundred times. I suppose you’d better say it yourself, repeat it.…No, that won’t do, that won’t do, don’t say it. You must feel it. You must feel it. See, here are these lovely trees and this lovely donkey, all these lovely lines—what do you want with words?”

The little girl’s face, with its features, soft and delicate as they were, yet bearing an unmistakable resemblance to his own, was tilted mischievously upwards, full upon him. She liked this familiar game they were playing. She glanced across the room to where Leah sat silently fuming, then placed her finger on her lips and said softly, “She shows me nice pictures in the paper with words all over.”

“Damn!” exploded the man, half turning, so that the portfolio nearly tumbled to the floor.

There came a laugh from the other side of the table, from Lora, who was passing through on her way from the kitchen to her bedroom.

“Still at it?” Lora observed. “You know perfectly well it’s no use, Albert. You can’t train a child in two hours a month. Anyway, she thinks you’re playing a game.”

“It would work if you’d help me instead of laughing,” he grunted. “By god, it’s got to work.”

No use arguing, thought Lora, as she proceeded to the bedroom.

“By god by god,” put in Roy, helpfully.

“Oh, be quiet!” the man exclaimed. “Here, hold this end. Look, Helen, look here, see the panther? With the grass all around him? These pictures were made by a man in Africa—wait, get your geography, Roy—no, no matter, no matter—seethe panther, Helen? Isn’t he lovely? Wouldn’t you like to be a panther and lie in the grass? That would be a good name for you—Panther. I’m sick of Helen anyway. I think we’ll have to call you Panther. Lora!” He raised his voice to carry to the bedroom. “Lora, we’re going to call Helen Panther! What do you think of that?”

He felt a hard grasp on his arm and turned to find Leah there, her black eyes flashing menace. “It don’t matter you think if you wake up a sick baby,” she spat. “You should care if Maxie’s baby dies.”

“Oh, I forgot. I’m sorry. Really.” He turned another page of the portfolio.

Roy was making faces at Helen and repeating over and over, “Panther, Panther, Panther.…”

Leah shrugged her shoulders, tiptoed across, and silently opened the door into the room where Morris lay.

Lora, in her own room with the door shut, was lying on the bed, on her back, her eyes closed. She was tired, not painfully tired, but she needed to rest, and to get away from the people out there. It was amazing how complete an annoyance Albert Scher could be—mild enough, nothing desperate, but completely an annoyance; and as for Leah—oh, well, it didn’t matter. All that did matter was inside her, in her womb. She loved the word, though she never spoke it. Now she repeated it aloud to herself, “Womb, womb.” Heavens, what a word! No man ever thought of it, a woman did that. Within her own was a warm comfortable feeling, full and pleasant. That’s ridiculous, she thought, it’s too soon to feel that way. I just imagine it. She placed the palm of her hand flat on her abdomen, but the dress was too thick to feel properly, so she unhooked it at the side and pulled up the underwear and got her hand against the warm bare skin and rubbed it, gently back and forth, up and down, from right to left and back again, then let it lie there, still. Ridiculous, she thought, I just imagine it.

Yes, she was tired; she had been going since early morning. Doctor Hardy had been a nuisance, fussing around; that baby was perfectly all right, he breathed like a top. A top doesn’t breathe. All right, all right. If Leah loved him so much, why didn’t she wash out his diapers once in a while? But that was unfair; Leah was really a big help. Only there was that to be done, and feeding the others, and getting her own breakfast and lunch—squeezing ten oranges and straining the juice took half an hour. She would have to stop nursing the baby, that was too bad; anyway, it would take more time to attend to his bottles, and heat the milk, and mix that stuff in it.…Leah was so tragic about everything, could she be trusted to do it right?

Even with Leah coming in nearly every afternoon, and the colored girl for three hours each morning except Sunday, there was too much to do. She wanted time to read a little, to get her stockings and dresses fixed up, to get a manicure and a shampoo with Nouveautone.…Why then did she not accept Lewis Kane’s offer and let him furnish the money for a nurse and a full-time maid, the rent for a larger apartment, a car to go around in? She made a face at the ceiling. Damn his money. Damn every-body’s money. Not that she had any neat conviction of superiority to it, or any harassed spirit of personal independence against a world of threatening and malevolent impingements; she was merely irritated at its elusiveness. Apparently, she thought, there was no hole deep enough to give it, buried, the peace of security; those who had it seemed to be compelled to hold on with finger-muscles strained even more frantically than those who were still grabbing for it. She had had to grab for it too, but never with any great degree of violence; she had been lucky. “I’ve been lucky all right,” she said aloud to the ceiling. Then suddenly she shivered and closed her eyes, and her hand, still inside her clothing next to the skin, was pressed tight and tighter against her firm round belly. “I’ve been lucky about money,” she said.

Nevertheless Lewis’s offer must be accepted, soon. Soon it would be a necessity. And why not? Was she not carrying his son? Daughter? No. He was determined it should be a son. What if there should be five daughters one after another? Ten. Twenty. A thousand; an endless sequence of daughters, all in a row, the most recent an infant at the breast, the earliest a towering giantess with her head bumping the moon. Or even if it were just a thousand, that would be nine thousand months, nearly a thousand years—more than seven hundred anyway.… Maybe some of the old Jewish women in the Bible actually did it.…

She stirred, rolled over and sat up on the edge of the bed, and tossed back her head to get the reddish-brown hair out of her eyes. Then she lay down again, on her side with her cheek resting on her upturned palm.

Child of love. She smiled with good-humored contempt; that, she thought, was a masterpiece among the meaningless phrases men have devised regarding children born out of wedlock. Look at that, you had to use another one to tell what you were talking about!

The man who invented “child of love” should have seen Lewis Kane that night two months ago. Whether he had for some time maintained bachelor quarters separately from his home, or whether the apartment had been prepared especially for this occasion, she had not known. It had not looked new; the furniture, clean and comfortably worn, had a settled air not to be found in a transient atmosphere. Lent by a friend, perhaps, she had thought, though that didn’t seem like Lewis. They had driven straight there after a late dinner; Lewis, after sending the chauffeur off with the car, had carried her little bag to the elevator, and on the twelfth floor to the door at the far end of the wide hall. Inside, he had turned on the lights, hung his hat and stick in the foyer, carried her bag to the bedroom and placed it on a chair, and returning to the large sitting room had lit a cigarette for her and started one himself, though he usually preferred a cigar.

“There’s no one about,” he said. “I thought you would be more comfortable.”

She nodded her thanks. “You’re a much more thoughtful person than you pretend to be.”

He waved it aside. “It’s merely a matter of common sense.”

“And sensitive. You’re really quite sensitive.”

“I don’t know. I think not. At the present moment I am in a situation popularly supposed to be emotional. If I am sensitive why am I so calm about it? Not that you are not charming; very charming. Chiefly I am concerned about our purpose; it doesn’t matter what I feel or don’t feel so long as I don’t flunk it when it comes to the point. I confess that I have been restless all day, for these things are beyond our control. In that respect you are fortunate; you have no responsibility. Doubtless you have noticed my uneasiness?”

“I—really—I—” She gave it up and threw back her head and laughed, a little louder and longer than need be, for she was on edge herself, not embarrassed exactly, but shaky a little, even a little indignant. She thought, he’s really an ass, the only thing he has forgotten is a pamphlet on hygiene.

An hour later she was in the room in front, in bed, with the covers turned down expectantly on the other side. A lovely, disturbing sight: her hair, almost black in the dim light, in sharp contrast to the white skin and the flimsy white gown, brushed smooth and glistening, seemed to whisper an invitation to urgent ravishing fingers; her bare arm curved across the coverlet; her half-exposed breast, large with milk, was at once shameless and a denial of shame. She was looking up and sidewise at Lewis Kane, who stood beside the bed wearing tan silk pajamas with enormous purple stripes, the corner of a white handkerchief sticking out of the breast pocket. He was standing up straight, and she thought to herself that he looked big and powerful and quite determined. And rather silly. She wanted to laugh again, as she had laughed in the other room.

“Do you want a drink of water, Miss Winter?” he asked. “No? I drank two glasses; I always do. I suppose I’d better turn out the lights. Do you want them all out?”

She said yes, and watched him go to the wall and press the switch, and then heard him return, more slowly but without hesitation, through the darkness. He got into bed, pulled up the covers, and lay on his side facing her and began at once to talk.

“It sounds pretty awkward, that Miss Winter. I think I shall have to call you Lora. You might call me Lewis, I suppose. These things seem unimportant, but we live so much by words and formulas that I imagine their effect is considerable—like the recoil of a shotgun. By the way, my uneasiness is over, thank heaven. One of us is to be congratulated—gallantry would say you.”

Lora, embarrassed at last, lay on her back without replying, her eyes closed. Why should she help him? It was he who wanted a son. If he thought he could get one by talking.… But suddenly she felt his hands firmly and surely grasping her shoulders, the pressure gradually increasing, and she let her eyelids open—the barest slit—and smiled.

She awoke because something heavy was on her chest and it was hard to breathe. Struggling painfully out of sleep, she gasped for air and with an effort pushed out her upper ribs against the weight that restricted them. What could it be? There was pain too, a real pain…then as sleep left, memory came and she sat up in bed and cupped her hands under her breasts. They seemed to weigh a ton. The milk, of course. She hadn’t intended to go to sleep at all. What time could it be? Lewis’s deep breathing came regularly from the other pillow. She got to the floor, groped around in the dark for her clothing, dropped a stocking and found it again, and made her way down the hall to the sitting room and turned on the light. A clock ticking on the mantel said a quarter-past two. She yawned, rubbed her eyes, and smiled at the neat pile of Lewis’s clothing at one end of the long narrow table.

Half an hour later she was seated in the dining room at home, with Leah, who obviously had not slept at all, standing and glaring at her, while the baby industriously tried to make up for lost time. Lora was smiling and thinking to herself, “Certainly he needn’t have been so uneasy. It’s all a fake, his not feeling anything. His wife gave him a scare, that’s all.” She never saw the apartment again. A week later, at dinner with Lewis, at the same inconspicuous little restaurant, he expressed his belief that another effort might not be necessary; and in another fortnight she was able to announce the probability that he was correct. “Splendid, splendid!” he exclaimed as he dished the broccoli. She wasn’t surprised, she explained, she was that way, she needed no more than a hint. Lewis went on to say that he supposed she was up on all the modern technique, he felt that he could safely leave all that to her, but did she have a good doctor? No, she admitted, as a matter of fact she didn’t, Doctor Hardy was competent but too fussy; whereupon he produced from his pocket a card containing a name and address and telephone number, saying that he had made careful inquiries and that no better was to be had.

It was on the afternoon that Albert Scher came to visit his daughter and gave her another lesson in the esthetic necessity of removing the art of line from all contact with literature, that Lora first noticed a look of suspicion in Leah’s sharp black eyes. Of course Leah was always chronically suspicious, but this look was specific and direct. Bah, Lora thought, Leah had from the first been annoyed by Albert’s visits, infrequent and exclusively paternal though they were, and on this day the annoyance was increased to the point of rage by the doctor’s insistence that Morris be kept in the house. Nevertheless, sooner or later Leah would know, and there would be the devil to pay. A good thing she wasn’t Italian instead of Jewish; give that stuttering passion of hers a few drops of blood from the toe of the boot and the problem would be serious. But, thought Lora, that could wait; there were other more pressing problems. Should she begin taking money from Lewis? Bah, he wouldn’t be the first, why not? Was this the way women who were married felt about it? But she was much too realistic to let herself be confused by that quibble, she knew that had nothing to do with it; married or unmarried, the question is at bottom purely personal, each case unique. It was because Lewis was so damned direct, “For one male baby,” he said in substance, “delivered in good condition, complete, I’ll pay a thousand weekly installments of two hundred dollars each. Here’s the contract; look me up in Bradstreet’s.” Like that he would buy a baby. Oh, no, he wouldn’t; not her baby, not the baby she already imagined she was beginning to feel. But there was the rub; he really was going to pay adequately, more than adequately according to the current market. What, in fact, would be a fair and reasonable price for an A Number One baby, guaranteed pure and unadulterated? One-tenth of one percent benzoate of—Oh, piffle! His money was no different from any other money; what’s the use, why make so much fuss?

She got up and crossed to the dressing-table and sat there brushing her hair; from the next room she could hear Albert’s rumbling bass, the leaves of the portfolio turning, and now and then an exclamation from Helen or Roy; no doubt Albert would say at a fresh discovery of the esthetic delight of the pure line.

The following day even Doctor Hardy admitted that Morris’s breathing was above suspicion, and when Leah came in the afternoon she was allowed to bundle him into the carriage and take him to the park. Lora, leaning from a window, watched them safely across Central Park West; you could never tell when Leah’s contempt for an alien civilization might explode into a calamitous disregard of the physical properties of a speeding taxicab.

The rest of July and most of August were hot. The sun blazed down from above, and New York’s pavements took the heat, mixed it with a thousand odors, increased it by some secret process to the temperature of a blast furnace, and hurled it up into the gasping faces of its citizens. Lora stuck it out. It was far from pleasant, what with the irritability of the children, a two weeks’ indisposition of Helen’s, Leah’s torrents of perspiration, and the morning nausea, but though Lewis suggested an Adirondack hilltop or a place at the seashore, Lora decided that it wasn’t worth the vast complication of the journey. She took off her clothes and lay on the floor somnolent in the heat, or went to the park with Helen and Roy and sat gasping on the grass while they tumbled around oblivious to thermometers. At home the new Swedish maid, paid out of the proceeds of Lewis’s first checks, was sweating over the vacuum cleaner or the washtub.

Lewis had not insisted on the seashore; he had suggested it, enumerated its advantages, and then quietly accepted her decision not to go. A few days later he had departed for Canada, headed for a little chateau in the Saguenay country where there was golf and trout-fishing, leaving behind him a card with the address typewritten on it and an invitation to wire him if any difficulty arose.

“Difficulty?” said Lora. “What difficulty could there be?”

“I don’t know. I’m quite ignorant,” he replied. “Don’t bother to write.”

So every few days she sent him a line or two to say that the union of chromosomes (this, long previously, from Albert) was proceeding without hindrance. There was no word from him, but each week an envelope came from his downtown office—Kane, Hildebrandt & Powers—containing a check neatly folded into a crisp blank letterhead. Surely less than impeccably discreet, she thought, but doubtless the intricate machinery of the legal factory of which he was the head somehow incorporated this weekly disbursement with an ambient indistinguishable vapor that would defy all analysis. The checks were generous and made many things possible. She bought Roy a velocipede and Helen a doll that walked three steps, and new clothing for all of them; she repaid Leah several hundred dollars which she had borrowed the preceding winter; she rescued from the pawnshop the necklace with platinum links and clasp which Max had given her the day after Morris was born; and one Sunday afternoon early in September she told Albert Scher, who was making his first paternal visit since July, that he need no longer bother about his monthly contribution to her household purse. Albert, seated on the floor trying to make Helen’s new doll go without falling over, looked up at her and blinked.