2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Publishdrive

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

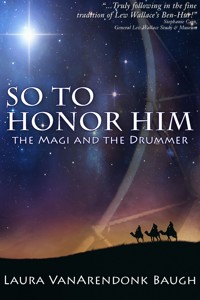

Arash is a slave drummer accompanying the Megistanes and other scholars on their journey to find the new king, whose star they have seen in the heavens. He does not understand their enthusiasm for this Jewish child, prophesied centuries before by one of their own, but each night he plays his drum for his master and dreams of earning his freedom.

When they reach Jerusalem, Arash is made an offer by King Herod himself: once they locate the child, return and tell him of this infant king of the Jews. For this small favor, Herod promises Arash’s freedom.

But Herod does not seek the child to honor him, and Arash is trapped in a plot to murder an infant.

Characters from Rome, Babylon, the Decapolis, and the Han Dynasty experience the events surrounding the Nativity in this meticulously researched and historically plausible retelling of the Little Drummer Boy carol.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

So To Honor Him

Laura VanArendonk Baugh

Copyright 2014 Laura VanArendonk Baugh

ISBN 978-1-63165-990-4

Æclipse Press Indianapolis, IN

First paperback and electronic editions published 2014. Second paperback and electronic editions published 2015.

Scripture quotations taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation Used by permission. www.Lockman.org

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher, except for the use of brief quotations as in a book review.

Dedication

Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile an account of the things accomplished among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, it seemed fitting for me as well, having investigated everything carefully from the beginning, to write it out for you in consecutive order, most excellent Theophilus; so that you may know the exact truth about the things you have been taught.

For all the eyewitnesses and servants,

Chapter One

“But he plays a woman’s instrument,” the tall man observed, his dark eyes faintly disgusted. “How useful could he be?”

Arash did not look up. They would not want to see his eyes, would not want to see anything that tasted of defiance. He needed to appear obedient, quiet, compliant. He could not afford to displease this customer too.

He had not gotten a good look at this man, but that hardly mattered. It was not his place to evaluate his future master, but rather to be evaluated. And while Hooshman had erred in advertising this particular young slave’s unconventional musicianship, he would hold it Arash’s fault for failing to meet his customers’ heightened expectations.

“I believe he had the learning of it from his mother,” Hooshman said. “You cannot expect that slaves would know the right of things. But he is passing fair at it.”

The tall man shook his head. “No, I don’t want to pay the higher price for a musician when he can’t even play for my guests. I’d look foolish with a boy playing. No, show me something else.”

Hooshman’s mouth tightened and he waved Arash away. “No matter,” he said, “no matter, there are plenty of others.”

Arash heard the restrained note of frustration and winced inwardly, knowing Hooshman would find some blame in him for this lost sale. Fingers tight around his skin drum, Arash bent low and started back toward the door, the metal shackle chafing his ankle.

Before he reached it, another voice spoke. “I’d like to hear the boy play.”

Arash stopped and waited, his eyes on the floor. Hooshman turned. “Forgive me, good sir! I did not see you enter. You wish to hear him?”

“It’s hard to judge the worth of a musician without hearing his music,” the second customer said reasonably. “But I will wait, if you wish to finish with this gentleman first.”

Arash could imagine Hooshman’s consternation, caught between two customers. “Why wait?” he said quickly. “The boy may play for you while I take this gentleman on to see other stock. If that pleases you?”

“It does.” Arash heard the creak of a chair settling under weight. “Please.”

Hooshman snapped his fingers. “Go and play, boy.” Arash heard the unspoken threat: Acquit yourself well. Sell yourself. Do not disappoint.

Arash went to the newcomer and knelt on the floor, cradling his drum. “What would it please my lord to hear?” he asked, his eyes on the man’s feet. They were wealthy feet, well-tended and clean.

“Play what you like,” the man said. “Whatever you think shows your skill.”

Arash nodded once, drawing a slow breath. He did not like the onus placed upon him; it was easier to fulfill an order than to anticipate a desire. But the man seemed to be interested in a drummer, and so Arash would show him his best drumming.

He set the drum firmly in his support hand, exhaled in a long stream to steady his fingers, and began to play.

He started with a brisk rhythm, a syncopated series calling both high and low tones from the skin drum. Then he began to slap the drum over the continuing rhythm. Sharp metallic notes leapt above the throbbing bass called from the center of the skin. His fingers leapt upon the surface, tapping and brushing and stroking, and he introduced a quick rolling sequence that made his fingers flash too quickly to be seen. He rocked slightly with the music, his own pulse lost in the beat of the drum.

He pressed the rhythm faster, driving to a crescendo, and then let it crash into quiet, a mere heartbeat of sound which ran on for a half-dozen breaths, and then he finished with a flourish and a final deep-toned slap.

The silence was oppressive, and Arash hardly dared to breathe. The music had shown a number of techniques, it had been by turns both energetic and soulful, and surely, surely this interested stranger would care to hear more?

“He’s not what I expected,” came a comment from across the room. The first man had paused in the doorway, rather than following Hooshman on to look over the other slaves. Arash, still looking at the newcomer’s feet, could see peripherally the first man half-turning to Hooshman behind him. “I may take him after all. What are you asking for him?”

“With the greatest of respect,” said the second man, “I believe I have the greater claim, as it was I who asked after him only after you had passed him over.”

Arash’s stomach writhed within him. He could almost hear Hooshman’s grin — with two customers interested in the slave, it might be possible to drive up the price, and there would be no chastisement for failing to present himself well. Yet there was always fear with any sale, going to a new master.

Arash swallowed, waiting to hear the debate over who would take possession of him. But the first customer gave a small sniff and said, “Well, then, as you wish. It’s nothing to me; he’s only a novelty.” And then he turned out, so that Hooshman had to hurry after him.

Arash sat still, wondering if the man who had been interested to hear a slave boy play would be a kind master, or at least a fair one.

“Raise your face, boy, and let me see you.”

Arash lifted his chin, but kept his eyes lowered.

The man sighed. “Look at me, then.”

Arash did, able to freely observe him for the first time. The man wore Persian garb, a belted tunic and many-folded trousers, of rich fabric but practical. His beard was short and neatly trimmed, and his mustache nearly obscured his mouth. He observed Arash for a moment. “Were you always a slave, boy, or were you sold for debt or some other cause?”

“I was born a slave, master, in the Roman territory.”

The man nodded. Slavery was uncommon in Persian culture, and Arash might have as easily been a freeman. But he had been born in Roman territory, the child of a slave, and so Hooshman, a Persian who traded between his own country and the Roman cities, was free to sell him as he might a table or donkey.

“Roman territory? Do you speak anything besides Persian, then?”

“I was raised to speak Greek. And,” Arash hurried to offer, “a little Aramaic, from Idumean slaves in the household.”

“Well, that will be useful. What’s your name?”

“Arash, master, if it pleases you.”

“It does please me, Arash, as did your music. Could you play for a company on a journey, to keep them content when the comforts of home are left long behind?”

“Of course, master.”

He nodded. “Then I shall buy you of Hooshman. It will be a long road yet, but in the end there’s much to like about Tyspwn.”

Arash caught his breath. Tyspwn was the capital of Parthia. He had not dreamed of returning to the heart of his mother’s country. And if his new master took him to a land where slavery was rare, might it be… could it come to pass that he might be granted his freedom? Could he earn it more rapidly in such a place?

He nodded obediently and dropped his eyes again. It would not do to display such hope openly, especially not here while yet in Hooshman’s house. There was time enough to discover what lay ahead.

Arash’s new master was called both Saman and Marcus Corvidus, as he was Persian nobility by birth and a citizen of Rome by his own accomplishment. This seemed to lie somehow in a service he had once rendered a senator. More, Saman was one of the Megistanes.

Arash had heard his Persian mother speak a little of the Megistanes, but he remembered only that they were hereditary priests and ministers of the court. They were supposed to be great scholars, he thought, the wisest of men.

Within a few minutes of their arrival at the inn, Saman had consigned Arash to a tall Greek with orders to turn Arash over to someone called Tannaz, and then he disappeared to other rooms, trailed by another servant with a sheaf of papers and tablets. For half an hour Arash sat in the yard, waiting for Tannaz, and listened to the inn’s guests and servants gossip.

Tannaz turned out to be the Megistanes’ chief steward, a dark-skinned man who immediately accused Arash of fleas and sent him to bathe. Arash, who did not have fleas, did not argue. It was unwise to present a first impression of recalcitrance. Once identified as troublesome, all a slave’s actions were viewed through a veil of prejudice.

The slaves’ bath was clean and serviceable, if lacking in ornamentation. Arash unclasped his arms from about the frame drum he had held close all the while and set it to one side.

Carrying the drum into the bath might affect its voice, as the skin would absorb some of the humidity of the room, but Arash had nowhere to leave it outside and would not be separated from it, anyway. Slaves could own property, in many cases, but Arash had only the drum and his own skin. The drum had been his mother’s. It was about the length of his forearm, a simple frame of wood with goat skin stretched across it. It bore no decoration. She had taught him to play as she did, even though he was a son, and often she had sung to accompany his drum — until he had been sold away to the city of Philadelphia, six years ago.

He placed the drum on a low bench and shed his clothes. Despite his resentment of Tannaz’s allegation, the water did look inviting.

He sluiced water over himself and then ducked his head, soaking his dark, waving hair and scrubbing himself clean of dust, dry skin, and any fleas which might somehow have leapt on him between Hooshman’s and the bath. He took a few extra minutes to stretch and rub his limbs in the warm water, enjoying the time to himself; privacy and introspection had been rare in Hooshman’s mercantile care. Then he rose, toweled himself, and began to dress in the new clothes which had been sent to the baths with him. Probably Tannaz had distrusted his clothing, too.

He turned back to the bench where he had left his drum, but it was empty. He glanced from side to side, but it had not fallen to the floor — as if it somehow could have, after Arash left it safely flat.

Arash’s stomach tightened and twisted, and he spun in place, looking vainly about the small bath. That drum was his only possession, his best memory of his mother, and the sole barrier between Arash’s sale as a musician and his sale as a sweeper of camel dung. And it was gone.

A chuckle escaped over a low wall, and someone laughingly shh’d the laugher. Arash bolted for the door and swung with one hand on the frame to face three teen boys, who turned to face him. “Give it back!” Arash demanded.

The crouching boys rose and fanned slightly so that they flanked Arash against the wall. Two were taller than he and the third was broader. “Give back what?” the broad one asked.

Arash looked at each of them. “Give it back,” he repeated. “My drum.”

“Your drum?” repeated a tall one. He had blond hair and a lean, muscular build. “Why would you have a drum?”

“My master purchased me for a drummer.” Arash wanted his voice to be even and firm, but it wavered even to his ears. “I must have it or be found delinquent.” He wished he knew if these boys were slaves to the same master Saman, and thus could be threatened, or subject to some other man and therefore immune from any threats Arash might make. Or they might even be freemen, wholly untouchable unless Arash could bring a reasonable argument to a new master who had no reason to believe an unknown slave over the word of freemen.

“Your master will be disappointed in you, then,” said the other tall one. He had straight brown hair which needed cutting. “Because I haven’t seen any drums around here.” He looked at the broad one. “Have you seen any drums around here?”

They laughed.

Despair began to throb in Arash’s chest. “Please,” he tried, “just return it to me. I’ll say nothing. Only give it back.”

“Look how quickly he begs!” the brown-haired one jeered.

“Give what back?” repeated the broad one. He was unoriginal, Arash noted, but that made him no less problematic.

“Unless you mean the drum in the pool outside?” The blond grinned.

Arash’s heart seized for an instant, and then he bolted half-dressed into the yard. He raced through the yard to the little pool where the beasts of burden were watered. It wasn’t far, as it shared a water line with the baths. A little fountain supplied it from the channel, and there on the corner of the sluice hung the drum, one edge of its round frame hooked tenuously over the edge of the waterway. It rotated slightly as occasionally splashes of water reached it and spun it on its point of balance.

Arash climbed onto the edge of the pool and stretched out his arm, but his fingertips could not reach the drum. He reached to rest a hand on the waterway to stretch further, but it moved with his weight and he jerked back.

Laughter came from behind him. “What’s the matter?” pressed the broad one. “Haven’t you found your drum? Aren’t you happy now?”

Two of them must have hung it together, or one of them must have tossed it with great precision — or luck. But Arash couldn’t drop it into the water now and risk its ruin. He bit fiercely on the inside of his lip, trying to think of a solution against the hooting laughter behind him.

“Jump for it!” called the blond. “Go on, jump!”

Arash had already seen it. If he could leap from the lip of the pool, he might snatch the drum before splashing down into the pool itself. He would have to shield it from the water, but it was his best hope if he were to retrieve it himself.