16,99 €

16,99 €

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

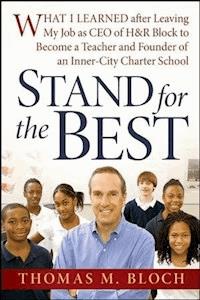

Thirteen years ago, Tom Bloch was CEO of H&R Block, the groundbreaking tax organization. The son of the company's founder, he was a happily married 41-year-old executive, but something was missing from his life. After a nineteen-year career at the company, Bloch resigned his position to become a math teacher in an impoverished inner-city section of Kansas City. Stand for the Best reveals Bloch's struggles to make a difference for his marginalized students and how he eventually co-founded a successful charter school, University Academy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 326

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Praise

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 - OFF THE BLOCK OFF THE BLOCK

CHAPTER 2 - BACK TO SCHOOL

CHAPTER 3 - INTO THE TRENCHES

CHAPTER 4 - ON THE LEARNING CURVE

CHAPTER 5 - ON OF CHARACTER A QUESTION OF CHARACTER

CHAPTER 6 - A NEW KIND OF URBAN SCHOOL

CHAPTER 7 - GREAT EXPECTATIONS

CHAPTER 8 - MAKING THE GRADE

CHAPTER 9 - MOVING THE SCHOOL

CHAPTER 10 - REAL HEROES

CHAPTER 11 - A DUTY TO DREAM

CHAPTER 12 - THE NEXT URBAN TEACHER

CHAPTER 13 - A CALLING

CHAPTER 14 - MIDTERM EXAM

EPILOGUE

APPENDIX

NOTES

SELECTED WEB SITES

INDEX

Copyright © 2008 by Thomas M. Bloch. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass

A Wiley Imprint

989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741—www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wileycom/go/permissions.

Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Jossey-Bass also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bloch, Thomas M.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN : 978-0-470-63959-7

1. Education, Urban—United States. 2. Bloch, Thomas M. 3. Mathematics teachers—Missouri—Kansas City 4. Charter schools—Missouri—Kansas City. 5. Teaching—Social aspects—United States. 6. Career changes. I. Title.

LC5131.B58 2008

371.10092—dc22 [B]

2008001014

HB Printing7

“I have so many books on my list to read and I rarely find the time or inclination. They all start sounding the same after a while. Not this one. It’s like a steamy mystery but better. Tom Bloch’s story is beyond good. It’s real—about what a man who had everything in the proverbial sense did to restore a notion of excellence to schools that is all too often missing. It’s a testament to what matters most, with keen insights into the failures we’ve endured in urban schools and a prescription for change that can no longer be overlooked.”

—Jeanne Allen, president, The Center for Education Reform

“Thomas Bloch is one of those rare people who ‘walk the walk’ and put their ethics into practice. His extraordinary efforts to educate so many forgotten children, and to figure out the business of education, prove that people truly can change the world. Stand for the Best is well-written, compelling, thought-provoking, and inspiring. I believe Tom has achieved his goal of doing something important with his ‘one and only life,’ and I hope his example will be wildly contagious among America’s business leaders.”

—LouAnneJohnson, author of Dangerous Minds, The Queen of Education, and Teaching Outside the Box

“Mr. Bloch rewards readers with a humorous, honest, and hugely upbeat book. You will feel good as you go through Bloch’s encouraging, entertaining story.”

—Joe Nathan, director, Center for School Change at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey Institute

“On his way to finding his life’s purpose, Tom Bloch identifies and tackles from many perspectives one of America’s biggest challenges: providing educational equity for all its children. The story of his journey is written with humility, honesty, and humor. This is a wise book that will both inspire and help those who are similarly seeking.”

—Linda L. Edwards, dean, UMKC School of Education

“Tom Bloch’s transition from CEO of H&R Block to inner-city math teacher in Kansas City is a selfless portrait in educational leadership.... Bloch’s devotion to his students, his community, and his loving family hold vital lessons for the nation. In this profound treatise his vision and courage are as striking as they are understated.”

—JohnBaugh,Margaret Bush Wilson Professor in Arts andSciences; director, African and African American Studies,Washington University in St. Louis

“What an inspiring and enjoyable book! Stand for the Best describes Tom Bloch’s fascinating journey from a successful CEO to an outstanding teacher and founder of an inner city charter school. The author also shares his valuable insights on the keys to personal success and the importance of giving back to one’s community. I highly recommend this book to anyone who wants to have a rewarding career and make a difference in the world!”

—Dr. Michael Song, ranked as the World’s #1 Innovation Management Scholar

“Stand for the Best should be read by any educator who wants to make a memorable difference in the dreams, character, and lives of young people, especially those who face tough odds. It should also be read by any person, whatever our calling, who wants to leave a lasting legacy for good. I loved this book.”

—Tom Lickona, co-author, Smart & Good High Schools; director, Center for the 4th and 5th Rs, State University of New York at Cortland

“Why would a guy turn in the keys to the CEO suite? In Tom Bloch’s case, it’s because he heard a call to do something radical with his life: serve inner-city kids. Stand for the Best is the surprising, engaging story of a corporate leader who discovered real power in helping kids find the potential others had ignored. For those who follow the school-policy wars, the book is particularly valuable for its lack of ideological cant. Bloch’s insights about charter schools, character education, and teacher training emerge from his own first-hand experience in urban education.”

—NelsonSmith, president, National Alliance for Public Charter Schools

The Jossey-Bass Education Series

Dedicated to the extraordinary urban teachers who are spending their lives doing something that will outlast themselves

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS BOOK WOULDN’T HAVE BEEN possible without the encouragement and support of my family. First and foremost, I thank my wife, Mary, who was also my first editor. Because her name will appear throughout the pages that follow, I’ll simply say here that I’m grateful for her love. I’m also indebted to my two sons, Jason and Teddy. Both of them were away at college when I began writing this book, but they were more than willing to critique drafts of the chapters when they were home on break. Having been accustomed to helping them with their homework when they were younger, I enjoyed the role reversal.

As a young kid, I always thought I had the best mom and dad in the world. And I still feel that way. My parents, Marion and Henry Bloch, always cared more about the happiness of their children than about their own happiness. I’m thankful for their encouragement and love.

I can’t say enough about the wonderful help I received from Dennis Farney in structuring and editing the chapters of this book. I feel fortunate to have worked with Dennis, whose distinguished journalism career included recognition as a Pulitzer Prize finalist. I value his terrific talent and coaching—and now his friendship.

Jeff Herman, my agent, sought to find a good home for my work, and he succeeded. That home was Jossey-Bass, thanks to editor Kate Bradford. Kate took an immediate interest in my story and offered superb input and guidance to improve the manuscript. She seemed to know exactly what was missing and what needed to be changed. I hope this book is a source of pride to Kate, Dennis, Jeff, and all who contributed to it in one form or another.

This book also wouldn’t have been possible without my students, each of whom has helped me grow as a teacher and as a person. I also thank the teachers and administrators from whom I’ve learned over the years. In particular, I want to acknowledge the three administrators under whom I’ve had the opportunity to teach: Lynne Beachner, Patricia Henley, and Cheri Shannon. I appreciate their leadership and support.

A special thanks to Barnett Helzberg, a cousin, a mentor, and the chairman emeritus of University Academy. And my thanks also go to the other board members of University Academy and everyone connected with the school, including parents Rose Kershaw and Elnora Woods, and educators Clem Ukaoma, Darran Washington, John Veal, Jason Balistreri, Tracie McClelland, Kellie Baker, Karen Howard, and David Wolff, each of whom contributed to this book. I’m grateful, too, for the assistance of the faculty and staff at the Institute for Urban Education at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, including Jennifer Waddell, Ed Underwood, and Omiunota Ukpokodu. My gratitude also goes to educators Joan Caulfield, Janel Atwell, and Tina Akula.

Finally, I want to acknowledge all of the associates at H&R Block who were understanding and supportive of my career decision. The greatest joy of my career at the company was working with its many dedicated and talented individuals. I’ve always been thankful for the opportunity to be associated with the company that my dad and uncle founded. H&R Block continues to mean a great deal to me.

Any profits I receive from this book will be used to promote an equal educational opportunity for all children.

INTRODUCTION

IN EARLY 1995, quite deliberately, I stepped down as CEO of H&R Block, where I was making nearly a million dollars a year. I had decided to follow a higher calling: teaching math to inner-city kids. This is the story of how that decision changed my life and the lives of kids I tried to help.

The decision was the most painful one I have ever made. It made no sense in conventional career-building terms. But worse than that, I was leaving the family business, a nationally known tax preparation firm that my dad had cofounded with little more than an idea and a $5,000 loan from his aunt. He had built it from nothing; I agonized about letting him down. But the bottom line, for me, was intensely personal. I wanted to leave my own kind of legacy with my one and only life.

What followed over the past thirteen years has been an education—for me even more than for the kids I tried to teach.

As CEO, I had directed tens of thousands of employees from a quiet and spacious corporate office. Suddenly I was teaching mostly poor, mainly African American students in a makeshift classroom in an inner-city school. At H&R Block I dealt with motivated, upward-striving employees. Now I had to try to motivate kids who, all too often, lived hour to hour.

“I have no future,” one told me.

I had been warned, but nothing quite prepared me for the spirit-crushing realities of the inner city. There was the father who was arrested at the school’s front door for possessing drugs. Other parents were sullen or even openly hostile. There were kids who went “home” to homeless shelters. There was the disgruntled former student who came back to school with a carload of friends and assaulted two staff members.

Amid the turmoil and the setbacks, I made discoveries that cheered me. I met bighearted volunteers like Rose and Elnora who made the school better through sheer force of will. I learned what a tremendous force for good even one such volunteer can be. I met dedicated teachers who somehow kept going despite a daily buffeting—and, more than that, kept their idealism intact. This book is also a tribute to them.

Urban education lies at the heart of our most urgent national problem. Our public schools should be, as they were intended to be, engines that lift the poor into the middle class. Yet, as everyone knows, urban education has been in crisis for decades. How do we teach inner-city kids? This book explores a number of ideas, including one promising innovation, the charter school. I eventually “graduated” from my makeshift classroom to cofound a $40-million charter school in Kansas City, Missouri. It’s called University Academy, and it now enrolls eleven hundred students from kindergarten through twelfth grade. But I don’t want to mislead anyone. University Academy has faced its own challenges. Charter schools don’t have all the answers. Nobody does.

This, then, is the story of an idealist’s journey. The idea to write a book had been in the back of my mind for years, but it wasn’t until just two years ago that I decided to actually do it. Being somewhat reserved, however, I admit that I had to overcome reluctance about revealing my thoughts and experiences to public scrutiny.

“You’ve always been such a private person,” my longtime and respected friend Debbie Smith remarked in surprise. She knows me well, having arranged a blind date for me in 1979. I later married that date. My wife, Mary, has been a pillar of support and encouragement throughout my career and the writing of this book.

The novelty of a CEO who traded status and power for teaching in front of a blackboard drew more national attention than I could ever have anticipated. It began with a front-page story in my hometown newspaper, the Kansas City Star. “Bloch Making His Mark in the Classroom,” the caption read. National media followed. There was a feature in People magazine followed by a segment on Oprah. I appeared on the Today show and in the New York Times, among numerous other media outlets. I was in the spotlight so much during my second year in the classroom that I sometimes felt more like a rock star than a teacher.

But I wasn’t a star of any kind. I was a relatively inexperienced teacher who had suddenly become a poster boy for the profession. That was particularly evident when my picture appeared on the cover of Teaching Pre K-8, a national magazine for teachers. None of the teachers I knew and worked with, most of whom were plenty more experienced than I, had received recognition outside their classrooms. They deserve it. I consider dedicated and gifted teachers to be genuine heroes.

“Don’t feel guilty about the attention you’re getting,” a colleague told me more than a decade ago. “Your publicity is raising the level of respect for the teaching profession.” I hope this book will contribute to that end.

In the chapters that follow, I have changed the names of my students (except for Tina, who is first identified in Chapter Three, and Jenell and DeAndré in Chapter Eight). Also, many of the individuals I’ve described are composites of actual people I’ve known. And identifying details about individuals and the circumstances in which they are presented have been changed. Finally, I would note that there are quotations in this book that are reconstructions of conversations as best as I can recall them.

I do not regret my decision to leave the corporation for the classroom. The English novelist E. M. Forster put it well: “We must be willing to let go of the life we have planned, so as to have the life that is waiting for us.”

CHAPTER 1

OFF THE BLOCK OFF THE BLOCK

I KNEW THAT I was fortunate. I knew that by all rules of common sense, I should be content.

But I wasn’t. I couldn’t shake the feeling that something—something big and fundamental—was missing. What was missing was a life outside H&R Block.

I was CEO, and the job was consuming my life.

I was making nearly a million dollars a year. But I was also worn out—from worrying. I worried about the company, the next quarter, the next tax season. I thought about the business day and night, which made it hard to focus on my wife, Mary, and our sons, Jason and Teddy. My friends used to tell me I had the world by the tail. But I felt the weight of the world on my shoulders—which was ironic, given that I often criticized myself for doing too little.

It was 1994, and I was completing my eighteenth year at H&R Block, the nationally known tax preparation and financial services firm head-quartered in Kansas City, and my fifth year as president. I oversaw tens of thousands of employees worldwide from my spacious office, dominated by a collection of original editorial cartoons that covered one whole wall. Each cartoon mentioned the company in some context. One of my favorites had a 911 operator telling a caller, “We’re only allowed to connect you to the police, fire department, or hospital ... you’ll have to call H&R Block yourself.”

That cartoon reflected reality: H&R Block had made itself almost indispensable, preparing one out of every ten tax returns in the United States. In fact, it had created a whole new industry. There were no retail tax preparation firms when my father, Henry Bloch, and his brother Richard founded the company in 1955. (Although the family name is Bloch, pronounced Block, the brothers substituted the h for a k to avoid mispronunciation. After all, you’d never take your tax return to someone who would “Blotch” it.)

Today, H&R Block dominates the market it did so much to create. As one profile of the company puts it, “Only two things are certain in this life, and H&R Block has a stranglehold on one.”1

I was proud of our success, and my pride had an extra dimension. H&R Block still felt like a family firm, even though it had gone public in 1962 and had grown tremendously, diversifying into computer and temporary help services. The family now owned well under 5 percent of its stock. But Dad remained chairman when I was CEO, and woven into that company were the history and aspirations of two Bloch family generations.

Dad and his two brothers, Leon Jr. and Richard (better known as Dick), grew up in a middle-class Kansas City household. My grandfather Leon Sr. was a lawyer who owned a few rental houses in low-income neighborhoods. Much of his legal practice involved helping his tenants and their friends and relatives. My grandmother Hortence, who ran the household, was a disciple of Ralph Waldo Emerson. She kept his essays, journals, and poems in her sitting room.

Dad’s biography is spelled out on the company’s Web site. He attended the University of Michigan thanks to Kate Wollman, a wealthy aunt in New York City who paid his college tuition. (The Wollman Skating Rink in Central Park is named after Kate and her brothers.) After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Dad enlisted in the Army Air Corps and then left school during his last semester when he was called to active duty. (In 1944, he received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan.) As a navigator of a B-17 bomber, he flew thirty-one missions over Germany, including three over Berlin. He had some narrow escapes and earned the Air Medal and three Oak Leaf Clusters.2

In 1946, after the war and a one-year stint as a stockbroker, Dad and his older brother, Leon, started a Kansas City bookkeeping service they called United Business Company. Aunt Kate helped them launch it, although in retrospect it appears that she may not have been quite as optimistic as they were. Dad and Leon asked her for an investment of $50,000. She responded with $5,000—in the form of a loan that she required their father to cosign.

For a while, that loan appeared to be in jeopardy. Business was so slow that Leon quit to attend law school. Dad, determined to keep going, looked for an assistant by taking out a help-wanted ad. His mother was the only person to respond.

“Hire your younger brother, Richard,” she ordered.

“I can’t afford to hire Dick,” Dad replied. “He’s married.” Then, an obedient son, he did hire Dick, and the two brothers tried to make a go of it.

In 1951, when the business was on firmer footing, Dad married Marion Helzberg, a beautiful, red-haired graduate of the University of Missouri. Their families had been friends for years and were members of the same temple. And three years after that, I was born—as it happens, one day before the filing deadline. While Mom was in the delivery room, Dad was in the waiting room, filling out tax forms for the company’s bookkeeping clients.

Looking back, it’s highly ironic that Dad and Dick came very close to dropping the tax preparation portion of their business. It wasn’t making money at first, and it required them to work seven days a week during the hectic tax season. In fact, H&R Block might not exist today were it not for the intervention of John White, a client who also was a display advertising salesman for the Kansas City Star. White urged them to operate the tax preparation business separate from the bookkeeping business—and to place a $100 ad in the newspaper.

“But we would need to prepare twenty returns just to break even!” Dad protested. (The going rate was $5 a return in those days.) Actually, White countered as he smoothly upped the ante, it would be better to run two ads while they were at it. Dick insisted on giving the idea a try, and Dad went along, expecting little, fearing the worst.

It was good that he did. On the morning the first ad appeared, Dad was making the rounds of bookkeeping clients when he got an urgent phone message to call the office. “Hank, get back here as quick as you can,” Dick shouted. “We’ve got an office full of people!”3

That was 1955, the company’s breakout year. Quite by coincidence, the IRS helped the company along just then by discontinuing its free taxpayer assistance program in Kansas City. Meanwhile the brothers changed the name of their company to H&R Block and grossed $20,000 in tax preparation revenues.

By 1978, H&R Block was a household name throughout the country. That was also the year that Dick was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer and was told he had ninety days to live. Instead of giving up, he got a second opinion and embarked on an aggressive treatment plan. In 1982, after he had defied the odds and defeated the disease, he sold his interest in the company. He dedicated himself to helping others fight cancer.

Two years before Dick’s illness, I joined the company, after graduating from Claremont McKenna College. I learned the business by preparing returns in a local Kansas City tax office and serving in a variety of positions at the corporate headquarters. I oversaw the automation of the tax business, and in 1981 I became president of the tax division. In 1989, at age thirty-five, I was elected president of the company. Three years later, I succeeded Dad as CEO.

Dad went out of his way to avoid pressuring me to succeed him. Nevertheless, even before I was thirteen, when he assigned me to sweep tax office floors, H&R Block somehow seemed bound up with my self-image and my expectations of the future. Once, in third grade, my class was asked to draw pictures of what we wanted to be when we grew up. The other kids drew things like fire engines and police cars. I drew a man sitting behind a desk.

Now I was behind that desk. Being CEO certainly had its satisfactions. Probably the biggest one was the feeling I got when I would make an executive decision and then feel the company respond beneath me, changing course like some great ocean liner. And it was especially satisfying when changing course proved to be a good decision. But I simply couldn’t leave my office problems at the office door. They followed me home, and I couldn’t let them go.

Mary said I was having, at age forty, a midlife crisis. I suppose that is as good a label as any, but I don’t think it captures the depth of what I was feeling. It wasn’t that I was seized by some midlife desire to buy a sports car or run away to Tahiti. I was in the grip of something far bigger than that. I wanted my life, my one and only life, to make a bigger difference.

Whatever the label, I had been in conflict for some time. It wasn’t because of one single thing. It was because of an accumulation of things.

I’m a worrier. I felt that if I worried about something long enough, it wouldn’t happen. And it usually worked. Sometimes I worried about big things. What if Congress passed a flat tax? That kind of simplification could result in a tax return the size of a postcard, which certainly wouldn’t be healthy for business. Sometimes I worried about small things. Was I traveling enough to our outposts during tax season? But whether my worries were big or small, I was always worrying about something.

I didn’t sleep well at night. I would wake up Mary at two in the morning. She hated that.

Before I go any further, I want to say that Mary, an attorney, is as tolerant of me and my idiosyncrasies as any husband has a right to expect. For example, she would say—and I would have to admit—that I’m frugal, especially when it comes to spending money on myself. Notwithstanding our income, we lived in a comfortable house, but hardly a lavish one. This was okay with Mary. But occasionally, especially earlier in our marriage, I carried my frugality too far, almost to the realm of tightwad. At least Mary forgave me for the time years ago when I gave her, in all seriousness, a Christmas gift of halogen lights from the Home Depot. (It had seemed like a logical choice to me. We needed better lights in the basement. But I’ll never forget the horrified looks on the faces of my in-laws. And I’ve noticed that since that time, Mary has been exceedingly specific about her Christmas list.)

Mary would listen to my 2 A.M. monologues—to a point. To me, each corporate crisis was distinct, and each demanded a new round of agonizing. But to Mary, more down to earth than I, each was simply another episode in the same long-running story.

Eventually she would say, “You’re repeating yourself. I’ve got to get some sleep. Just let it go.” She would turn over and be back asleep almost instantly. I’ve never seen anyone go from wakefulness to sleep so fast; it was a feat comparable to a racecar going from zero to ninety in five seconds. And I would still be lying there, alone with my thoughts.

Mary began to worry about my health. “You’re going to kill yourself,” she warned one day. “At the rate you’re going, you’ll be dead by fifty.”

My relentless agonizing took a toll on family life. “You aren’t even listening to us,” she told me one evening at the dinner table. “Your son Jason just asked you a question, and you didn’t even hear him.”

Tax seasons unfortunately coincided with our sons’ basketball seasons, and I always hated to miss their Saturday games while I was holed up at the office. It was equally painful when I returned home to hear Mary recount like a play-by-play sports broadcaster a pivotal basket or steal that one of them made.

We usually vacationed in Phoenix over the boys’ spring break from school. But it wasn’t unusual for me to return to Kansas City after only a day or two to contend with a business crisis that was brewing. Mary wondered whether it was always necessary for me to get back to the office. Now, on further reflection, I’d have to admit that her doubts were justified.

I tried to change. I read a couple of self-help books. I exercised religiously. Nothing worked. I remained implacably, stubbornly myself.

I also discovered that I didn’t have much of a social life. I had scarcely any hobbies beyond cutting brush and clearing hiking trails on the wooded farm we owned near Kansas City.

I felt hemmed in by the life I was living. If I was ever to be fulfilled, I was going to have to do something else.

But what? Gradually my thoughts turned to teaching. Even though I’d had only two brief experiences as a teacher, I realized that I had found unexpected satisfaction in teaching.

My first teaching experience began with a casual decision made for the most mundane of reasons. “There is an opening for a French teacher at the elementary school in Claremont [California],” my French professor mentioned to me after class one day. “I thought you might be interested. You won’t get paid, but you’ll earn course credit for the semester.”

I was only twenty years old and had never taught before, so I think I learned more by teaching these fifth-grade students than they learned from me. I can’t pretend that the experience was entirely pleasant. I was just a college student, and I don’t think the kids quite took me seriously. As a case in point, they promptly named me “Mr. Blockhead.” But on the whole it was enjoyable and gratifying to see the kids learn the basics of a new language.

My other teaching experience was at H&R Block, which operates the country’s largest tax preparation school, with more than two hundred thousand students enrolling annually. It was early in my career, after having completed the company’s thirteen-week tax preparation course and then working for a season in a local tax office.

Teaching that tax preparation class was tougher than teaching those fifth graders because, at the time, I probably knew less about the intricacies of the tax code than I knew about French. But it too was satisfying. A decade later I encountered a tax preparer I had taught. Still with the company, she had developed a large and loyal clientele and had become a tax instructor herself. “You probably don’t remember me, Mr. Bloch,” she began. But I did remember her, and it was fulfilling to know that my teaching had helped her along the way, and that she also had decided to help others through teaching.

These two prior teaching experiences were indirectly influential in my decision to switch careers. The main lesson I learned from them was that teaching—and reaching out to others—can produce a great sense of satisfaction. When I thought about these experiences, I recalled the good feeling that came from making a commitment to others.

But if I was interested in teaching, where would I teach? Where could I do the most good? My thoughts turned to the inner city.

Why do so many inner-city kids fail to use school as their ticket to the middle class? Why, after decades of intensifying national effort, from desegregation in the 1960s to the No Child Left Behind program of today, hasn’t more progress been made in educating these kids? Is it the fault of the school districts? The teachers? The parents? The kids themselves? Isn’t there some way to overcome the low expectations that hobble kids before their lives have scarcely begun? Is this really the best we can do?

Kansas City, Missouri, was as good a place as any to seek answers to these questions. Its public school system embodied all the problems of urban school systems everywhere. I did some research to find out where the problems were coming from.

For decades, Kansas City’s public schools were starkly segregated, not by law but by the de facto segregation that kept African Americans confined to their ghetto. Everybody had a neighborhood school, but the black schools got far less money than the white schools. One school board member complained that rainwater dripped into buckets in his son’s classrooms, and insulation hung from holes in the ceiling.4

But if segregation was a persuasive explanation for poor academic achievement in the 1960s and 1970s, it seemed less persuasive by the 1980s and 1990s. With the end of redlining (the refusal by lenders to make loans in particular areas based on their racial makeup) and other unlawful practices, the city’s African Americans surged far beyond the boundaries of their old ghetto. To be sure, a good deal of de facto segregation remains a fact of life in Kansas City. An otherwise nondescript street named Troost Avenue is still an invisible but universally recognized boundary between two cities, one black and one white. But in just about every other way, from increased funding to sparkling new schools, Kansas City has worked hard to give its minority kids a chance.

The impetus for much of this effort was a sweeping federal school desegregation ruling in 1984. The court held the State of Missouri liable for the deplorable state of black schools. Between 1985 and 1995, the state, under duress, pumped more than 1.5 billion new dollars into the Kansas City system. Striking new schools were built, featuring the latest in computers and audiovisual equipment and, in one case, an Olympic-size swimming pool. The district was reorganized, with newly formed magnet schools offering a menu of choices from college prep to French immersion. Essentially, any student could ask to go to any school (space permitting), and if a bus route wasn’t available, the district would pay for his or her taxi ride.

The hope was that the sparkling new schools would keep white parents from moving to the suburbs and attract white children back from the private schools that many of them attended. This didn’t happen; in fact, district enrollment as a whole has continued to decline. But perhaps even more discouraging, academic achievement has been stagnant. A 2006 study of the district by the Council of the Great City Schools, a coalition of the nation’s largest urban schools, concluded that Kansas City students ranked “well below peers statewide, and their performance has not been getting much better of late.” About the most positive thing the study had to say was to praise the courage of the Kansas City School Board for inviting the study in the first place.5

Personally, I could think of no better way to make a difference than by teaching inner-city kids. But let me be clear about this. I knew I wouldn’t be doing this just for the kids. I would also be doing it for myself. I wasn’t sure if I could really change the lives of Kansas City students or have much of an effect on the quality of the schools, but I felt I had to try.

I had several heart-to-heart talks with Dad as I agonized about a new direction for my life. Finally, in early 1995, I told him I had decided to leave the company. I had dreaded this talk for months.

He listened thoughtfully, receptively, as always. “I can’t believe it,” he said. “Take some time off. Get out of the office and take a real vacation with Mary. Think about this some more.”

So Mary and I went to Aspen. My mind seesawed between yes and no several times a day as Mary and I hiked and went cross-country skiing. But in the end it settled on yes: I was going to leave the company for teaching.

We wanted our sons to be among the first to know, but I wasn’t quite prepared for the reaction of six-year-old Teddy. I watched as an expression of growing concern crossed his face. “Are you going to be my teacher?” he asked. I reassured him that his private school already had fine teachers and had no need of me. He looked greatly relieved.

A couple of weeks later, I found a homemade card on the breakfast table at my place. It was from Teddy to me. On the cover, it said “Bravo!” Inside was the following: “Dear Dad, I hope you are a great teacher. I want to have as much time [as I can] with you. This is a great dicistoin [sic]. Love, Teddy.” His note reinforced a growing, if shaky, conviction that I had made the right decision.

In April 1995, H&R Block formally announced my decision to leave. I stayed on until August, until my successor was identified and on board. Then, on a typically hot and humid summer day, the day after I cleaned out my office, my father hosted a farewell lunch for me.

I was told it was going to be a small gathering, just Mary and me, my dad, and a few senior executives. I didn’t look forward to putting on a suit and tie, but I had no choice. It was very thoughtful of my father to host this luncheon for me. I put on an old suit, but Mary stopped me before we got out the door of our house.

“Oh, you can’t wear that old brown suit!” she said. “Why don’t you wear one of your nicer ones?” I had heard such words before. I don’t know how many times Mary had chided me over the years for “inappropriate” attire. Usually I had ignored this advice, and I ignored it again on this day. “It doesn’t matter what I wear,” I insisted.

We went to the Crowne Plaza Hotel, across the street from the corporate offices. Mary Vogel, my longtime executive assistant at the company, was there to meet us in the lobby. She looked annoyed and worried. There had been a mistake. There was no record of a reservation at the restaurant. However, the hotel had offered us a small conference room on the second floor.

When we got to the conference room it was utterly empty.

“Something must be wrong,” Mary said in disgust. “Let’s go across the hall and see if we are supposed to be in there.”

“But that’s the ballroom,” I protested. We went in anyway.

The ballroom was certainly not empty. In fact, it was filled with hundreds of people, sitting at tables and waiting for their lunches to be served. I was about to remark that we had apparently crashed some kind of convention. But then everyone turned toward us and began applauding.

I looked more closely at the faces in the room. They were all H&R Block employees, including Kansas City associates as well as senior field leaders from out of town. It finally hit me. This was a surprise party ... for me. My wife had a huge grin on her face. Obviously, she had been part of this. Now I understood why she had been so adamant that I wear a nice suit. I began to wish that, for once, I had followed her advice.

The applause didn’t stop. I hugged both Marys, and we were escorted to a table where Jason and Teddy and my mother and father waited to greet us. Mom, beautiful as always, was putting up a brave front, but I knew that this was a bittersweet occasion for her. She, even more than Dad, had been stunned by my decision to leave. I hugged them all and sat down, and finally everyone else did the same. I tried as hard as I could to hold back the tears.