0,91 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

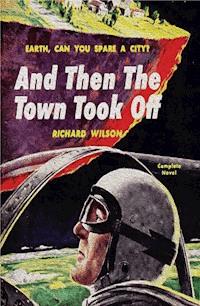

It was big news for reporters throughout the solar system. After a cargo-liner en route from Earth to Mars blew up as it was coming in for a landing, killing all eight persons aboard, the workers went on strike. Spacemen had walked out in a demand for higher pay and better retirement benefits. The spacemen’s union included not only pilots but crewmen, mechanics, and maintenance workers at the spaceports.

But was it a tragic accident—or sabotage?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 24

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

STRIKE, by Richard Wilson

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 1953, 1981 by Richard Wilson.

Originally published in Future Science Fiction, July 1953.

Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

STRIKE,by Richard Wilson

Herbert Gray, the president of the Interplanetary Spacemen’s Union, said, “It’s a slander on labor, and you can quote me.”

Art Roper of Galactic News Service had asked Gray to comment on the sabotage-angle, in the case of a cargo-liner which had been en route from Earth to Mars. The ship blew up as it was coming in for a landing, and all eight persons aboard had been killed. Fragments rained down on the outskirts of Iopa, killing a Martian and an Earth-child. In his question, Roper had quoted the remark of a spokesman for World Government Investigation that W.G.I. was looking into the possibility of sabotage.

The strike had been on for a month; spacemen had walked out in a demand for higher pay and better retirement benefits. The spacemen’s union included not only pilots but crewmen, mechanics, and maintenance workers at the spaceports.

“It’s a libel to suggest that any member of the I.S.U. could have been in any way connected with the unfortunate explosion aboard the cargo-rocket,” the union leader continued. “Our activates since the strike began have consisted of peaceful picketing and full cooperation with World Government mediators. The fault, if any, lies with Interstellar Carriers, and its refusal to discuss our just demands.”

A reporter for Interplanetary News asked Gray whether the explosion could have occurred if a union crew had been aboard the cargo-liner.

“As to that,” the union official said, “I can only point to the high safety-record of interplanetary travel, up to the beginning of the strike. You may recall my statement of three weeks ago—that space-travel requires the services of experienced men at every step of the journey, and that the employment of scabs—or so-called supervisory personnel—might detract not only from the quality of the service, but from its safety as well. However, to interpret that as a threat of any kind would be erroneous in the extreme.”

“Thank you, Mr. Gray,” Roper said. He and the other reporters dashed out of the news conference in the union leader’s suite at the Hotel Mars, scanning their notes as they raced to the press room to call in their stories.

* * * *

The strike had been one hundred percent effective for the first week. Many persons realized for the first time how dependent Mars was on Earth—not only for basic foods, but for little luxuries which had been taken for granted. Coffee, for instance.

Art Roper got meat with his meal at the restaurant, because he was a regular luncheon customer—others were being turned down. But there was no Earth coffee left for anyone.