Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Luca Caioli

- Sprache: Englisch

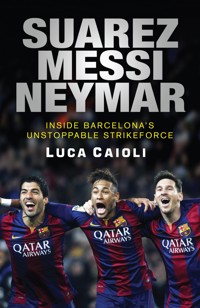

Bestselling football biographer Luca Caioli tackles his most controversial subject yet - Barcelona, Uruguay and former Liverpool forward Luis Suárez. When in late September 2013 Luis Suárez returned from a landmark ten-match ban for biting an opponent, one in a long line of high-profile misdemeanours, it seemed unlikely that he would ever win over his critics. In the months that followed he scored an astonishing 31 times, propelling Liverpool back into the Champions League following a four-year absence. The World Cup in Brazil followed but Suárez saw his action-packed tournament curtailed after just two games, two goals and one moment of madness, with favourable comparisons to Messi and Ronaldo once again overshadowed by those with Jekyll and Hyde. Acclaimed football biographer Luca Caioli provides an in-depth look at one of football's most enigmatic characters, from humble Uruguayan beginnings to his big-money move to Barcelona in July 2014.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 348

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SUÁREZ

About the author

Luca Caioli is the bestselling author of Messi, Ronaldo and Neymar. A renowned Italian sports journalist, he lives in Spain.

SUÁREZ

THE REMARKABLE STORY BEHIND FOOTBALL’S MOST EXPLOSIVE TALENT

LUCA CAIOLI

Published in the UK and USA in 2014 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa

by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India

by Penguin Books India, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110017

Distributed in Canada

by Penguin Books Canada, 90 Eglinton Avenue East,

Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Distributed to the trade in the USA by

Consortium Book Sales and Distribution,

The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE,

Suite 101, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55413-1007

ISBN: 978-190685-077-7

Text copyright © 2014 Luca Caioli

Translation copyright © 2014 Charlie Wright

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in New Baskerville by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents

1 The connection

2 You know we love you

3 A powerful identity

4 Thermal baths, oranges and baby football

5 The long walk south

6 A lot of heart

7 A marvellous surprise

A conversation with Rubén Sosa

8 A love story

9 Time bomb

10 No limits

A conversation with Martín Lasarte

11 In the city of the north

12 Red and white

13 Hand of the devil

14 Come on, you light blues

A conversation with Jaime Roos

15 Bite and run

16 The best

17 ‘Negro’

18 A cannibal at Anfield

19 Rationality and irrationality

A conversation with Gerardo Caetano

20 News from the year of resurrection

21 The stairs

A conversation with Óscar Washington Tabárez

22 The saint and the delinquent

23 The connection 2

A conversation with John Williams

24 Repentance

25 New life

A career in numbers

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

The connection

7.30 Saturday morning: Roberto Mallón was behind the cast iron bar. He was fiddling with the coffee making machine. There was no need to ask as he knew what the customer wanted. In a flash, he had delicately placed a little white cup on a red saucer on the bar and filled a little glass with soda.

There were not many people around at this time of day in Bar Arocena di Carrasco. Just a couple of kids who looked like they had had a good night out the night before. One of them ordered a chivito, the house speciality: a succulent panino stuffed with ham, barbecued steak, cheese, tomato, lettuce, mayonnaise; the other kid ordered a Milanese cutlet the size of a horse. The order was rounded off with Coca-Cola. A good method to get rid of a hangover. A few tables away, three regulars religiously read El País and sipped on coffees.

Everyone in Montevideo knows this bar in Carrasco. It is always the last bar open when all the others have shut up shop for the night. The Arocena never closes. It is open on Sundays and at Easter, Christmas and even New Year’s Eve. It is open 24/7 and has been doing so for decades. It is a lifeline for solitary souls. So much so that some have called it El Salvador (the saviour). The bar has the atmosphere of a village pub even though it is located in one of the chicest areas of the city: green parks, low-rise housing which used to be the summer residences of the well-to-do at the start of the twentieth century but now are the fixed abodes of high society. But Arocena has let luxury and modernity pass it by. It still wallows in times gone by and is a place where anyone can get a drink and be politely entertained. It is an eclectic bunch who grace its doors: drunks, artists, footballers, rugby players, gamblers from the nearby casino, taxi drivers feeling the chill, workers who are grabbing breakfast before starting their shift, impoverished students, timewasters, Nacional and Peñarol fans, the Carrasco upper class, the elderly with a few pesos in their pockets. Dusty bottles line the shelves and there are 1950s shaped fridges, cigarette bricks lined up in a row and the Uruguayan football team pennants hanging above the bar. Photos, pictures and whisky and beer adverts from times gone by fill the walls. There is even an article from El Observador entitled ‘Historia de un Inmigrante’ (‘The Story of an Immigrant’). It tells the life story of Roberto Mallón. The Galician was born in 1936 at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in Agualada, a parish about 12km outside of Carballo and 30km from La Coruña. Galicia was a place where poverty was widespread. At eighteen, Roberto was sent to seminary with his brother and was on his way to becoming a priest (this was a common way to get out of poverty at the time). Roberto liked to read and in so doing he discovered South America: life was better there; there was work for everyone, or so it seemed. He quit the cloth and took the first boat he could. He arrived in the port of Montevideo, Christmas 1955. He started out working as a pot washer, cook, barman, bread maker. Roberto took any work he could get his hands on up and down the coast and in Punta del Este, including making pizza, bread, milanesas (breaded beef cutlets) and escabeches (a typical Uruguayan dish). Then in 1974, together with Alfredo, another Galician, he bought the Bar Arocena with his savings from the previous twenty years and it has never shut since.

At this point, the reading of the bar owner’s story was interrupted by the TV fixed to the ceiling. The sports correspondent was explaining about how the Uruguayans want to know about the Liverpool match: who had won, whether Luis had scored, whether he had beaten the highest number of goals scored in the Premier League, and whether he would claim the European golden boot ahead of the Portuguese star, Cristiano Ronaldo, and the Hispanic Brazilian, Diego Costa. The presenter stated that the Liverpool number 7 had paved the way for a new era in the Reds’ history and made them one of the most loved teams in the Premier League. The TV reportage reeled off image after image of the latest match and then delved into the analysis of the next match against Norwich City. The punters raised their heads to soak up the information. Roberto Mallón, who had learnt over the years to take insults, such as Gallego bruto (ugly Galician), Gallego quadrado (stocky Galician), on the chin and to still support with his heart and soul the Nacional team, moved closer to the customer. Mallón, with his shaven head, dark pinafore, tired eyes and Galician accent (despite having lived for years in Montevideo), poured another soda and quipped: ‘Lucho is awesome. Leading goalscorer in Holland and now in England … easier said than done. It requires something special to do that. It is unique. For me, alongside Messi and Ronaldo, he is the best player in the world.’ He points at the TV: ‘Look how they push him to the ground, crop him wherever he plays, be it with Liverpool or with Uruguay, as though it is completely normal and acceptable. He never gives up and commits 100 per cent. You can tell his formative years were with Nacional’.

Eduardo, part of the furniture of the bar, retorted: ‘Yeah but he only came good when he went to Europe. He was pretty average here. You remember when he used to have the nickname ‘Pata Palo’ (‘Wooden Leg’) at Parque Central’.

The man on Eduoardo’s table put down the paper and piped up: ‘That said, I like him. He is a tractor. You put him out to sow the seeds in any field covered in weeds and grass and he always does the job and cleans up. Nothing can stop him. Nothing gets in his way’.

There was a lot to talk about and it was not over. The drinks supplier ambled into the bar laden with Coke and Fanta. He left the door open so that he could unload the van. The words wafted down the Avenida Alfredo Arocena, a highway which cuts across Carrasco and then merges into the Rambla Republica de Mexico, right next to Hotel Casino Carrasco, a Baroque castle towering over the Rio de La Plata, opened in 1921 complete with ballrooms, games rooms, terraces, restaurant, stucchi and the domes in stained glass and which was the beating heart of the bella vita in the wealthy European must-see stop-off which was Montevideo in the first half of the twentieth century.

Just like Federico García Lorca who stayed there in 1934 and wrote part of Yerma, one of his best works which, together with Casa de Bernarda Alba (‘House of Bernarda Alba’) and Bodas de Sangre (‘Blood Wedding’), forms part of his trilogy.

Now Carrasco, after suffering several decades of neglect, and being revitalised in 2013, was home to another star. Paul McCartney was staying in the Imperial Suite of the hotel. He was staying there ahead of the concert he was performing at the Estadio Centenario. The TV and radio stations kept running the story. Orlando Petinatti, in his radio show Malos Pensamientos (‘Bad Thoughts’), announced to the ether: ‘I played football with Paul. He will come to my house and have a mate (Uruguayan caffeine-infused drink) and an asado (barbecue). I liked John and we played together’. Orlando waited for the reactions of the listeners.

Meanwhile, Hotel Carrasco was under siege. There were railings and barriers everywhere, police, security vehicles, bodyguards and a few hundred fans. There was a middle-aged lady with a huge bunch of flowers that she wanted to give to the ex-Beatle. There was a small girl who was holding a sign that read ‘Paul, sign me please’. There was a group of seven boys and girls from Paraguay wearing black T-shirts with the words ‘Paul New’ (the title of the ex-Beatle’s new album) in white lettering. All of the fans were desperate to see their idol and get an autograph and to say a few words to him. It was not to be. Sir Paul was whooshed away from the hotel in a blacked-out car and merely leant out of the window to wave to his fans.

There is someone who was lucky enough to speak to Paul McCartney before his ‘Out There’ concert and that someone was Luis Suárez. A question-and-answer session of four minutes on McCartney’s channel. The Liverpool number 7 asked him a bit about everything. As Luis’s son was born in Liverpool and his daughter was at school there, Suárez wanted to know all there was to know about Liverpool culture. Paul decided to talk about his old school, LIPA (now known as the Institute for Performing Arts), where he met George Harrison. They talked about his latest concert in Uruguay where a 50,000-strong crowd met to sing along to the Beatles songs which were still popular and still bringing people together all these years later. They talked about football, the World Cup, the Uruguay football legends who won the World Cup in 1950 (the Maracanazo). Paul said that he was his favourite player. They talked about Uruguay and England and Luis promised to dedicate a goal to Paul when England were eliminated from the World Cup and Uruguay carried on. Paul replied: ‘I don’t think things will pan out like that but dedicate a goal to me anyway’. The interview was over. It was time to say farewell and move on. Luis closed out by saying, ‘Thanks, Paul. I hope you enjoy my country and the lovely people who are there’.

‘The pleasure is all mine’, says Paul.

Paul chanted a special song from the Centenario stage: ‘LIVERPOOL, LIVERPOOL, EVERTON.’

Yes, Paul supports Everton! However, the Liverpool–Montevideo connection was already set in stone.

Chapter 2

You know we love you

Every city has its own way of presenting itself, of showing off its best side, of letting the visiting tourist know where he or she is and what the history of the place is.

Liverpool makes it blatantly clear where you are right from John Lennon airport. The car park is pointed out to you by a self-portrait of the late Beatle. It is a simple affair but a few flicks of a pencil let your brain form the image of the great man. In front of the airport, near the taxi rank is a Yellow Submarine in what looks like a life-size replica of the animated submarine from the Fab Four’s 1968 film.

Adi landed at the John Lennon airport under a turbulent sky. Black clouds and white clouds swirling overhead, spears of sunlight trying to burst through the threatening mass of swirling air. The odd shower scattered here and there. Adi had flown in from Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia. Yanti, his wife, had come along too. The black cab that took them from the airport to their hotel drove past billboards that set the scene: ‘Welcome to the most successful footballing city in the UK’, ‘It’s football. It’s Liverpool.’

The road ran alongside the Mersey estuary and gave an insight into what Liverpool was made of. You could see a mountain of containers, car dealerships galore with the latest brightly painted offers daubed on cars, lush bright green football and rugby fields, red-brick terraced houses, Indian takeaway restaurants, shopping centres, navy barracks and shipbuilding yards. Right up to the Albert Dock with its massive warehouses which at one time were full of cotton, tea, sugar, silk, ivory from all over the world, but which today hosts the Tate Museum and the Merseyside Maritime Museum, where there is an exhibition of the story behind the Titanic and Liverpool’s intriguing relationship with the infamous liner, as well as The Beatles Story, an exhibition dedicated to the revolutionary pop band.

Today the docks where the gigantic transatlantic ships embarked on the voyage to America, where millions of immigrants headed off for a new life, and where the commercial heart of the city beat loudly, are a UNESCO World Heritage Site – just a tourist attraction and no longer a bridge to the New World.

Adi and Yanti were not in Liverpool as tourists. They had not come to get to know Merseyside, England or go on a Grand Tour of Europe. No, they were here to see Liverpool’s last match of the season. They could not get their hands on a ticket to see the match at Anfield but they could not give up on the opportunity to live the experience from the city centre, where they could live and breathe the experience firsthand before, during and after the match. They wanted to be close to the team, share the joy and the pain with their fellow fans. Sporting his Liverpool FC baseball cap and red and white scarf, Adi was hanging around in Rainford Gardens with his camera, just two metres away from the large white banner which read: ‘Welcome to Mathew Street, birthplace of The Beatles’.

It is the road where the Cavern Club can be found, where the Beatles began their story; a mural tribute by Arthur Dooley remembers the Fab Four as follows: ‘Four Lads Who Shook the World’. It is the road of the pubs where the Beatles went after their concerts in the 1960s, where you can buy all things Beatlesesque. It is here that a statue of Carl Jung, who passed through in 1927, stands. Jung wrote of Liverpool: ‘It is the pool of life, it makes to live’. Not many remember the Swiss psychiatrist. There are thousands who come from all over the world to pay tribute to the band.

Adi, 44 years of age, a TV producer of reality TV shows and mini-series, had decided to film the street, the pubs and the passers-by but this had nothing to do with his job. It was just a deep ingrained passion to capture the city and the thousands of Liverpool fans who were waiting for the match to start.

It was 3.00pm on 11 May 2014. Anfield was hosting Liverpool vs Newcastle. The last act of the Premier League. The last 90 minutes to dream the unthinkable: a Premier League title, something which the Reds had not done for 24 years.

Adi explained in English that in Malaysia, an ex-British colony, for various reasons the Premier League is followed religiously. Every week you can watch all the matches. Adi has been a Liverpool fan since 1977: ‘I was seven years old and my brother told me that Liverpool was my team; since then I have never stopped following them. My hero at that time was Kenny Dalglish, then Robbie Fowler, then ‘El Niño’ Torres and now Luis Suárez, the genius. Words cannot describe what he is doing, together with Steven Gerrard, for the Reds. He loves winning and does everything to try and win.’ A genius with a temper … ‘He certainly does have his moments but everyone knows there is a fine line between genius and insanity.’

Adi and Yanti were not the only ones to have travelled hundreds of miles to be there for the last Liverpool match of the season. There was a sense of fraternity between the Liverpool fans. It is in the veins of all the fans from Ireland, Scotland, Northern and Central Europe, the USA, South America to the Far East. Red veins which bring together cities and countries, villages and continents. A shared identity and belief which cuts across skin colour, race, language, culture, religion, ideology, age and social standing.

Within a hop, skip and a jump you are in Whitechapel, L1, meeting new friends: three teenagers from South Korea. They all wanted a selfie in the red shirt. Jung-Su, wearing thick black-framed glasses, made his opinion on Suárez crystal clear: ‘He is lightning quick. He has an exquisite touch and he is so efficient; in the area he is an assassin. He does not let anything go.’ Jung-Su, a player himself, knew what he was talking about.

Hamar is a small town with 29,000 inhabitants in the region of Hedmarken, Norway. Frederick and his friends had come all the way from there in their red shirts. They explained that in the 1970s, Norwegian TV started to show a match from the English First Division every Saturday. This was the turning point for many Norwegians who like Frederick knew that Norwegian football was and still is rather dull and fell in love with Liverpool. Frederick is a good analyst of Liverpool’s famous striker: ‘He is not the same as [in 2012/13]. He is less selfish and plays for the team. He is not as alone up front as he used to be. He has found Sturridge and Sterling to be good teammates and they have helped him develop and grow just as with what happened to Messi and Iniesta and Xavi at Barcelona.’

Joachim, a Swede from Sölvesborg who had tagged on to the conversation, chipped in:

‘Brendan [Rodgers] and Stevie [Gerrard] had the trust in Suárez and Suárez returned the favour, big style. He showed he was a fantastic player.’

There were three hours to go until the start of the match. The centre of Liverpool was a sea of red. The buses from the other side of the Mersey offloaded a red army of fans, all dressed in uniform; the same thing was happening at Lime Street and the fans just kept on coming – every ten minutes. The ‘food’ vans – the hot dog kiosks, burger vans and chippie bars – were lost amidst a sea of red rumbling stomachs, looking for their pre-match top-up. The longest queue was for the hot dog stand, the prize: a ginormous hot dog in a white bun with lashings of onion, cheese and mustard stuffed into a paper serviette. Also popular were the trays of the traditional but unbeatable fish and chips soaked in what smelt like tractor oil. The red army ate, drank and made merry on the streets as they prepared themselves for the emotions and several pints of beer ahead. The street sellers lined the way with all sorts of Liverpool paraphernalia. It was a good business. It was unthinkable to enter the historic stadium of Anfield without the appropriate uniform: shirt, scarf and flag. It was important to let everyone know whose side you were on in the beautiful game that is football. The stalls had every sort of shirt and especially the one with number 7 on it or a scarf in honour of the Uruguayan striker. The writing on the gadgets was the same across the board: ‘Just can’t get enough’: the song which the Reds had dedicated to Luis, based on the homonymous Depeche Mode hit.

This was how Liverpool partied on a Sunday: a Sunday of worship of the god of football. It was a temple to which everyone headed to celebrate Anfield and the beautiful game. The 1884 stadium built to host Everton became the home of Liverpool in 1892. Around this iconic building, there was a feverish hum of excited fans getting more and more inebriated; friends greeted each other, football anthems and chants broke out sporadically inside and outside the pubs.

The TV reporters interviewed the fans; photographers looked to catch a special moment; policemen on horseback; stewards attempted to guide the mass of red into the stadium. There were kids of all ages dressed in the red uniform from head to toe. Kevin screamed: ‘Suárez is the best in the world’. Teenagers with their shaven heads painted with the Reds’ war paint and warrior tattoos on their arms gazed at the sky and let out a cry of disbelief as a light aircraft flew over the stadium trailing a banner with the words: ‘Manchester United 20 – Gerrard 0’. One of the fans mimed shooting the plane down with an imaginary machine gun. Two girls dressed to the nines, as though they were going to a Royal Gala, added the finishing touches to their lip-glossed lips – red of course. Bill, a gritty 60-year-old Scouser, leaning against the wall, cigarette perched on his lips and breathing smoke, spewed his tactical précis to the fans going by. In rough guttural Scouse, Bill laid it down: ‘I believe that Liverpool fans have supported Suárez in his moments of crisis. They defended him and treated him well; just as our slogan says: “You’ll never walk alone”; we did not leave him on his own. Luis felt this, understood it and appreciated it.’ Crispian, Bill’s wall mate, chimed in: ‘It is for this reason that I hope he stays with us at least for another two or three years.’

At the entry to the stadium, two metres from the Bill Shankly statue, a steward, sporting a hi-vis jacket, kindly explained to an American couple from Boston that there were no more tickets and pointed to the sea of fans around him so they got the idea. The steward told the couple to not be tricked by the ticket touts who were trying to still sell tickets. The couple were guided to a pub where they could watch the match on a large screen in peace with a cool beer in hand – well, not sure if they would enjoy the match in peace but the beer part was definitely right!

The couple were convinced and headed off to the pub, stopping at a club megastore on the way to buy a souvenir. The store was full of gadgets and people all emblazoned with Liverpool FC.

Outside the gates a balding man continued to play the bagpipes undeterred by the swarming crowd. People walked by, took a picture, dropped a quid in his hat on the floor and moved on.

Slowly yet surely, the mass of pint-glass-holding fans around the stadium started to filter into the stadium and the streets emptied. The moment had arrived, the kick-off was nigh. Time for one more beer at The Albert. Warren, squashed at the bar but fighting fiercely to keep his place, when asked about Suárez immediately smacked his chest with open hand and shouted: ‘He plays with his heart. We love him and he knows it.’

Chapter 3

A powerful identity

José Mujica is not a great lover of football. As a kid, as with all kids, he played football but at twelve he started to cycle and for three or four seasons, he dedicated all his time to cycling. He supports Atlético Cerro because it is the team where he lives and because when he was younger, Huracán del Paso de la Arena did not exist.

He is not a great lover of the ‘sphere’ but he knows that in Latin America, ‘the greatest form of communication is football which, together with language, is the strongest bond and relationship which can exist between societies in South America. A simple game has become something of the utmost seriousness and importance.’ A game which sometimes leads to violence in the stadiums: ‘the beast within us which threatens the heart of all societies’. Leaving violence to one side, Mujica is convinced that ‘Uruguay is one of the most football obsessed countries in the world.’ In a recent radio interview, he commented: ‘Relative to the size of the country and the potential of each citizen [there are 3.3 million people in Uruguay], Uruguayan football is a miracle created by the passion of our people.’

The nation’s President, who surprises the world with his laws (legalisation of marijuana, abortion and gay marriage) and his recipe for human happiness (as reported on by The Economist which awarded the country Country of the Year 2013), is right. He is not the only one to think like this. The footballing miracle is the topic of conversation in all circles of society: facts, numbers and statistics are trotted out to prove this by anyone you ask. The four stars on the light blue shirt of the national team remind the populace of the two Olympic golds (1924 and 1928) and the two World Cups (1930 and 1950); there were also fifteen Copa Americas. The generalised practice and routine of football: from the dusty side streets to the lush green pitches of the professional teams, from the streets to ‘baby football’ (every weekend Montevideo sees around 3,000 matches of baby football being played, a real social event for the families and the kids aged between five and twelve.) The national championship, across the first and second divisions, has 34 clubs, 29 of which are in the capital. The tickets to go and watch the matches are reasonable: 80 to 500 pesos (€2.50–15). This allows anyone who wants to go and watch a game. All of these matches are viewed for peanuts compared to the European figures: US$10 million for the TV rights in Uruguay compared to €1,229 million for the Premier League; US$15 million is the budget for Club Nacional against €520 million for Real Madrid. Pepe Mujica commented: ‘[This last figure] is probably an amount which Uruguayan football has not spent in its entire history’. And yet notwithstanding the money and the numbers, the footballing miracle continues and the tiny South American country fights its corner amidst the giants of Brazil and Argentina. It can boast a whole host of magical players as though it were a nation of 60 or 200 million inhabitants. Why? Because football is a passion (or illness) which runs through the veins of society at all levels. Because it is a country with weak national identity, where nationalism is not valued strongly and where national pride is placed in the light blue shirt and in antiporteñismo (anti-Argentine sentiment). Football is a powerful identity: a substantial and fundamental part of the culture of the nation. And it is getting even more powerful as it defines the role that sport and football plays in the value system of the nation. There is a real symbiosis between football and the country. Uruguay stops for two events and two events only: a national match and the general elections. Politics and football are central to life in the Eastern Republic of Uruguay. So much so that the list of Uruguayan heroes is peppered with footballers like Obdulio Varela, ‘El Negro Jefe’, who played in the 1950 World Cup and José Nasazzi, ‘El Mariscal’, who played in the 1930 World Cup. Football is the place where conflicts are played out, where great discourse is made and the source of the expressions which infiltrate the language: ‘Los de afuera son de palo’ (‘Outsiders don’t play’). This was the phrase which Varela famously said to boost his team’s morale before entering Maracanã packed with 200,000 fans. It is a phrase used to indicate that those who are outside the family, the group or the party do not count. It is better not to listen to the outsiders.

How this world was built, this powerful identity, has to do with the history of the Eastern Republic of Uruguay, even though it is hard to work out even today.

Football everywhere, as in Brazil, Argentina, Italy, Germany and France, is connected to the industrial revolution and the expansion of the English economy. It was Her Majesty Queen Victoria’s subjects who spread sport to every corner of the globe. Football arrived at the port of Montevideo in the luggage of the sailors, craftsmen, professors, workers, bank managers, railway personnel and gas company workers. At the end of the nineteenth century it came and got a foothold at the cricket clubs like Montevideo Cricket Club, founded in 1861.

The members of the club played not only in their whites and with their bats made of cork and leather but started to play rugby and football against teams from the merchant ships and the Royal Navy. One such match took place in 1878 along the coast near Carretas Point.

But the records show that it was only in 1881, on 22 June, that the first official match between two clubs from Montevideo took place. The match was played in the La Blanqueada quarter on a pitch which the English called the English Ground. The Montevideo Cricket Club against the Montevideo Rowing Club. The final score was 1-0 to the cricketers. Seven days later the rematch: the Cricket Club won again, 2-1. It was the Montevideo Cricket Club which hosted the first international match, on 15 August 1889, against the Argentinians of Buenos Aires Cricket Club. The locals watched the new pastime of the crazy English with detached bemusement but bit by bit the younger members of well-to-do society in Montevideo started to get hooked.

From behind his desk in his office just a stone’s throw from the stadium’s Amsterdam stands, Mario Romano, manager of the Centenary Stadium of Montevideo, explained: ‘In May of 1891, Enrique Cándido Litchenberger sent an invite to his schoolmates at the English High School to set up a Uruguayan football club. On 1 June 1891, it was done. The Football Association was set up and played its first match in August against the Montevideo Cricket Club. In September, the club changed its name to Albion Football Club in honour of the birthplace of football.’

It is clear to see that England was the inspiration for many clubs in the Eastern Republic, as for example the footballers of the College of Capuchin Monks. In 1915, they were looking for a name for their club and they took inspiration from the map of the United Kingdom. They remembered the explanations of their teacher in class: the students were taught that huge transatlantic cargo ships left from the port of Liverpool headed for Montevideo. After hearing this, they were in no doubt and decided to call their club ‘Liverpool’. The team still plays today in the second division. It is also worth considering the origins and diatribe of Uruguayan football which even today have not been agreed upon. It lies somewhere in the history of Nacional and Peñarol, the rivalry between the most important clubs in the country; the teams have won 93 of the 110 titles between them, plus eight Libertadores Cups and six Intercontinental Cups. On 14 May 1889, Club Nacional de Football was born from the merger of two university clubs (Montevideo Football Club and Uruguay Athletic Club de La Unión). Club Nacional de Football, the answer to the colonial teams. This is the reason the strip of the club is white, light blue and red, the same as the flag of José Gervasio Artigas, the father of the Uruguayan nationhood.

On 28 September 1891, in the north-eastern part of Montevideo, a group of mainly English workers from the Central Uruguay Railway Company of Montevideo Limited, formed the Central Uruguay Railway Cricket Club, known as CURCC or, for short, Peñarol (a name which comes from the area in the north-east of the city where the railway companies’ building yards were). Their colours were yellow and black like the railway signals. It was here that CURCC started to make its mark on the Uruguayan championship. In 1900, CURCC met three other teams, Albion, Deutscher and Uruguay Athletic in the Uruguayan championship. On 13 December 1913, CURCC officially renamed itself Peñarol. CURCC had played at least 50 matches against Nacional: Carboneros (colliers) vs Bolsos (pockets, as they used to play with a jersey that had a pocket on the chest), Peñarol vs Nacional; on the one side the English railway club, on the other the university elite; on the one hand the gringos, on the other the nationalistic elite. It was this rivalry that formed the backdrop to football in the salad days of the Eastern Republic. It was there that the passion for this beautiful game started to fill the veins of the nation. The sport spread like wildfire engulfing a generation of young men as it went. Other teams sprouted: Wanderers, River Plate, Bristol, Central, Universal, Colon, Reformers, Dublin …

Matches were played against English teams such as Southampton, Nottingham Forest and Tottenham who were on tour in South America. The eternal rivalry between Argentina and Uruguay got under way in the Lipton Cup and Newton Cup.

Football was a social leveller. It was a place where the poor and rich could integrate and mix; immigrants mixed with the well-to-do. Between 1860 and 1920, Uruguay saw a mass influx of immigrants from Europe – Spain and Italy mainly – which changed the demographics of the country for ever. This European immigration was matched by the influx of African Brazilians, slaves in some cases, coming from nearby Brazil. The mixed-race population was key to the composition of Uruguayan society. In a country without serious inter-class tensions and where there aren’t deep-rooted aristocratic tendencies, immigrants, Africans and Hispanics are muddled together.

Lincoln Maiztegui Casas, history professor and author of epic political and social studies in Uruguay which cover the very beginnings of socio-political trends in Uruguay, explained the demographics as follows: ‘At the start of the 1900s, Uruguay was not an egalitarian society but it was integrated thanks to the experience of a social state and the education system reform in 1877 promoted by José Pedro Varela. School was non-religious, free and mandatory. The idea that a rich person’s son and a poor person’s son could go to the same school, use the same pinafore and same bow was born. It was a reform which created a surge for equality in society and slowly eroded the cultural differences between the indigenous population and the immigrants. The immigrants did not lose touch with their cultural roots but deep in their soul they feel Uruguayan.’

Football played the same role in helping to bring people from different cultures and classes together. You only need to take a look at the names of the national team which won the Paris Olympics in 1924, i.e. Petrone, Scarone, Romano, Nasazzi, Iriarte and Urdinaran, and you realise that the majority of the names are Italian and Spanish in origin. There was José Leandro Andrade, the ‘Black Marvel’, the first great black football player in the history of Uruguayan football. There is no question that football integrates and brings together. It is also a way to climb the social ladder. A great example of this was that of Abdón Porte El Indio. Maiztegui, being a great professor and orator and devout Bolso, told the story while sitting at his kitchen table behind a big pile of books:

‘He had won the championship with Nacional and he had won the Copa America in 1917 with Uruguay but the fateful day came when the coach told him that on Sunday he would not be in the starting line-up. Abdón could not live without playing football for Nacional. Football had taught him to live in society, to dress properly, to have a bath, to get a job, and to get a girlfriend. Thus it was that on 5 March 1918, in the Gran Parque Central, the Nacional stadium, he shot himself in the head. They found him the next day with the gun still in his hand.’

This was in the 1920s, the years of success for Uruguayan football.

Mario Romano explained as he ambled through the halls to the Football Museum at the heart of the Centenary Stadium: ‘There was no particular reason behind the Uruguayan success at the start of the twentieth century.’

The manager pointed out the shirts, balls, trophies, the boots of José Vidal, number 5 for the national team of 1924 and the large photo of Andrade. He stopped to explain and provide some detail about the national trophies. Then he picked up from where he had stopped a few moments before: ‘I believe it has a lot to do with the Rio de la Plata situation, with the economic power of Uruguay and Argentina, economic powerhouses at that time. They had not suffered the fallout of the First World War which had ravaged Europe. On the contrary, they saw a net increase in exports, capital investment and currency exchange. Uruguay was going through a period of growth, commercial and industrial expansion; it had a stable political regime with the state providing an advanced social welfare system and policies were in place to promote physical education which opened up the sports fields to the whole country. It was [Uruguay’s] football in particular which made its mark on the Old Continent. Football had come to conquer the world and conquer it did. In Paris in 1924, Uruguay won the Olympic tournament beating Switzerland 3-0 and amazing the fans.’

Henri de Montherlant, a French novelist and playwright, wrote: ‘A revelation! This is true football. The one we knew, which we played, compared to this it is just a school pastime.’

Maiztegui added: ‘Uruguay was a small country which did not stand out on the world map; it made a name for itself in Europe not for its literary culture inspired by the French, not for its musical culture with strong Italian influences but for its footballers.’

It was in Paris at the Colombes stadium that the legend of garra charrúa (Charruan tenacity) started to embed itself in the public consciousness. The organisers did not know how to identify the players from Uruguay and so requested that a Frenchman dressed in traditional Uruguayan clothing stood in front of the Uruguayan cohort. The Uruguayan players were shocked. Their parents and grandparents came from Europe and the players did not know anything about the Indios and Aborigines who had lived in the East Strip. The last Indios, the indigenous people of Uruguay, were killed in 1831 in the matanza de Salsipuedes (the massacre of Salsipuedes) by Jose Fructuoso Rivera y Toscana, the first Constitutional President of Uruguay. Those that survived and were imprisoned ended up being turned into slaves in Montevideo or sent to Paris and exhibited like a circus attraction. Thanks to romantic poets like Juan Zorrilla de San Martín, the legend of the brave and fearless warrior who fought to the death against any enemy in his way lives on. Garra charrúa was a divine gift that enabled a warrior to give that little bit extra when the enemy least expected it.

This battle quality was transposed on to the game of football and the Uruguayan ‘warriors’ of football. It became the benchmark for the national team.

At the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, Uruguay won a second gold medal, beating their eternal rivals Argentina in the final by drawing the first leg and winning the second. At the 1929 congress in Barcelona, FIFA decided to award the organisation of the first World Cup to Uruguay: a rich country which had not suffered the 1929 Wall Street crash and the Great Depression. It was experiencing what came to be known as los años locos (‘the crazy years’). The economy was booming. The peso was worth more than the dollar. Social mobility was on the up and the middle class saw its purchasing power improve significantly. Great warehouses opened up to manage the increase in demand for consumer goods; 15,000 cars were imported in one year alone. Montevideo was transformed: new residential areas sprang up, skyscrapers reached for the sky, hospitals, schools, universities, parks and stadiums (including the Centenary stadium) burst into life.