1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

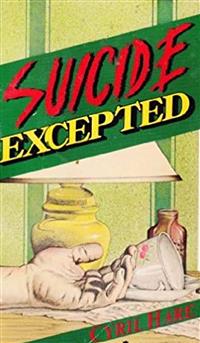

Suicide Excepted shows a man committing an almost perfect murder, only to find that a quirk of the insurance laws may deprive him of the reward.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Suicide Excepted

by Cyril Hare

Copyright 1939 Alfred Alexander Clark.

This edition published by Reading Essentials.

All Rights Reserved.

Suicide Excepted

To

Chapter One

The Snail and His Trail

Sunday, August 13th

As you come over the brow of Pendlebury Hill, just beyond the milestone that reads “London, 42 miles,” you see Pendlebury Old Hall below you. It lies a little way back from the road, a seemly brick-built Georgian house, looking from above like a rose-pink pearl on the green velvet cushion of the broad lawns surrounding it. You will probably think, if you are the type who has any leisure to think at all at the wheel of a car, that the owner of the Hall is a man to be greatly envied; and you must be very much pressed for time indeed if you do not slow down as you pass the wide entrance gates at the bottom of the hill to glance up the broad beech avenue at the simple and dignified façade of the house. At this point you will notice that over the entrance a board in lettering of impeccable taste announces “pendlebury old hall hotel,” and below, in smaller but still chaster type: “Fully Licensed, Open to Non-Residents.” Charmed by the sober beauty of the house, fascinated by the seclusion of its setting, your refined taste tickled by the good manners of the notice-board, you will decide that here at last is the country hotel of your dreams, where good cheer and comfort await the truly discriminating traveller. And that is where, English country hotels being what they are, you will be wrong.

Inspector Mallett of the C.I.D., sitting in the lounge of the hotel, wondered for the twentieth time, as he put down his coffee-cup with an expression of disgust, why he had ever been fool enough to enter the place. He was, he told himself, too old a hand to be caught in this way. He might have known—he should have known—from the moment that he set his foot inside the door, that it would be just like any other wayside motoring hotel, only more so, where the soup came out of a tin, and the fish had been too long on the ice, and far too long off it, where the entrée was yesterday’s joint with something horrible added to it, and the joint was just about fit to make tomorrow’s entrée, where tough little cubes of pineapple and tasteless rounds of banana joined to compose the fruit salad, where fresh dessert was non-existent—in the heart of the country, in mid-August! but then it was forty-two miles from Covent Garden—where bottles of sauce stood unashamed on every table, and where the coffee—he looked down again at his half empty cup, and felt for a cigarette to take away the taste.

“Did you enjoy your dinner?” said a voice at his elbow.

Mallett looked round. He saw a sallow, wrinkled face peering up into his with rheumy grey eyes which seemed to hold in them an earnest, almost desperate, expression of inquiry, quite out of keeping with the triviality of the words. Mallett recognized the symptoms at a glance—the craving for companionship of any kind, the determination to talk to somebody, no matter who, provided he would but listen—and his heart sank as he realized that to cap everything, he had fallen, bound hand and foot, into the power of an hotel bore.

“No, I did not.” The inspector answered the question shortly. He did not really expect to choke the fellow off so easily, but one could but try.

“I thought not,” said the other. He spoke in the muffled half-whisper habitually employed by the English in the public rooms of hotels. “But they didn’t seem to mind it, did they?” He nodded towards the other guests in the room.

Mallett was roused in spite of himself to reply. The stranger had touched upon one of his favourite subjects.

“That’s the whole trouble,” he said. “So long as the public eat this kind of food without complaint, one can’t expect to get anything different. It’s no good blaming the hotels. I suppose these people would really feel cheated if they were given two good courses for dinner instead of five nasty ones. As it is—”

“Ah, that’s just it!” the stranger broke in. “And, of course, with the best will in the world, you can’t serve five good courses every day, lunch and dinner, in this place. For the simple reason, my dear sir, that the kitchen isn’t large enough. If they had the capital to modernize it, it might be a different story, but they haven’t. And so they have to resort to the wretched apologies for dishes which we’ve had tonight. Every time I come here it gets worse and worse. It’s sad.”

And looking at him, the inspector saw to his astonishment that he genuinely looked very sad indeed.

“You seem to know the place pretty well,” he observed. “Have you been here often before?”

“I was born here,” he answered simply, and for a space was silent.

He was a man of sixty years of age or thereabouts, perhaps more, Mallett decided. Very clean, with thin grey hair and a shapeless moustache stained yellow with nicotine, he was an unattractive figure, but at the same time queerly pathetic. Mallett was surprised to find himself becoming interested in his acquaintance, and felt quite disappointed that he seemed indisposed to say more. He did not, however, care to break in upon thoughts that were evidently painful.

Presently the stranger roused himself from his reverie, and produced from his pocket a much-worn Ordnance Survey map of the district. From another pocket he took a mapping pen and a bottle of Indian ink. Then he unfolded a square of the map and began to trace upon it with great care a zigzag course.

“My day’s journey,” he explained. “I always keep a record.”

Looking over his shoulder, the inspector noted that the line which he had just completed was only one of many, several of them faded with age, and that all of them appeared to centre upon, or radiate from, Pendlebury Old Hall. For want of anything better to say, he remarked:

“You are on a walking tour, I take it?”

“Yes—or rather I was. This is my last port of call. It always is, you see.” He indicated the network of lines upon the map. “For many years I’ve spent my holidays walking in this part of the world—it’s wonderful country, it really is, when you know it well.” He seemed anxious to forestall any possible criticism. “And since I—h’m—since I retired, you know,” he lowered his voice, as though the fact of his retirement was in some way shameful, “I have more leisure, can start from farther afield. Why, one year, sir, I walked here all the way from Shrewsbury!”

“Indeed!”

“Can’t do so much now as I should like to, though. My doctor tells me—but it doesn’t do to pay too much attention to doctors, does it? But wherever I go, I always end—here.”

He contemplated the map with affection.

“Wonderful how the lines all centre on this place!” he murmured.

Mallett was tempted to comment that there was nothing really wonderful in the fact, considering that he had made them all himself, but the pathetic earnestness of the man kept him silent.

“I often think,” he went on, putting the map away again, “that if we left a trail behind us in all our wanderings like—like snails, if you follow me, mine would be found to be concentrated on this place. It begins here—for the first twenty years of my life it was here and hereabouts more than anywhere else—and now I’ve reached a time of life when I ask myself more and more often, where will it end?”

It was a thoroughly embarrassing moment for an undemonstrative man such as the inspector was. He could think of no better comment than to clear his throat loudly.

“Of course,” the stranger pursued, still in the same hushed undertone, “we have this advantage over the snail—we can make our trail end when and where we wish.”

“My dear sir!” said Mallett, thoroughly shocked, as he realized the full implication of the words.

“But, after all, why not? Take my own case, for example. No, not for example, I’m not interested in other cases—take my own case, for its own sake. I’m an elderly man, I’ve lived my life, such as it is, and believe me, I’ve had enough of it to know that the best of it is behind me. When my trail ends, I shall leave my family well provided for—I’ve seen to that, anyway. . . .”

“You have a family, then?” Mallett put in. “Then surely—”

“Oh, I know what you are going to say,” he answered wearily. “But I don’t flatter myself that they will miss me. They may think now that they will, but they won’t. They have their own trails too, and theirs and mine take different directions. My fault, I dare say. I’m not complaining, I’m just facing the facts. I shouldn’t have married a woman fifteen years younger than myself. She—”

He broke off suddenly, as some one walked behind Mallet’s chair and down the room away from them.

“Hullo!” he said. “Why that’s—no, I must have been mistaken. Thought it was somebody I knew, but it couldn’t have been. Those back views are deceptive sometimes. As I was saying—my daughter is very fond of me, in her way, and I’m very fond of her, in my way, but they’re not the same ways, so what’s the good of pretending that we are necessary to each other? I don’t like her—her friends, for instance, and that means a lot at her age.”

Mallett had begun to lose interest again. The fellow seemed to be merely rambling. The way in which after a casual interruption he had suddenly introduced the subject of his daughter, who had not been previously mentioned, when he had been in the full flood of discussing his wife, indicated an ominous lack of grip on his train of thought. But suddenly he jerked himself alive again, and said in a quite new, determined tone of voice: “I’m going to have a liqueur brandy. My doctor doesn’t allow it, but damn the doctor! We can only die once. And you are going to have one with me. Yes! I insist! There’s still some of the old stuff in the cellar that was here when my father was alive. You’ll like it. It will help to digest some of that horrible food you’ve just been eating.”

The inspector allowed himself to be persuaded. He felt that he deserved some recompense for having listened so patiently. When the drinks were brought, the stranger said:

“I like to know who I’m drinking with, and I expect you do too.”

He extended a card. Mallett read: “Mr. Leonard Dickinson,” followed by an address in Hampstead. He replied by giving his name, but concealed his rank and profession, which experience told him was apt to produce either an embarrassing constraint or a troublesome access of curiosity.

“Your very good health, Mr. Mallett!” said Dickinson.

The evening seemed likely to end on a mellower note than that on which it had begun. But when the glasses were empty, Dickinson reverted to the same subject.

“That was good!” he said. “It takes me back for a moment or two to the old days. To my family, Mr. Mallett, this is merely a third-rate hotel. To me, it is a place of memories—the only place where I have ever been in any degree happy.”

He paused, holding the empty glass between cupped hands, savouring the bouquet that still rose from it.

“That is why,” he added with quiet emphasis, “since my trail must end somewhere, I should like—I feel sure that it will end—here.”

He got up. “Good night, sir,” he said. “You are staying the night here, I suppose?”

“Yes,” said Mallett. “My holiday ends tomorrow, and I am making the most of it. I shall see you at breakfast?”

Dickinson allowed this innocent question to remain unanswered for quite a considerable time. Then he said softly, “Perhaps!” and turned away.

Mallett watched him walk with the gait of a tired man down the length of the lounge, saw him stop and say something to the girl at the reception desk, and then make his way slowly upstairs. He shivered slightly. The old man’s conversation had been too depressing. He felt as though a goose had walked over his grave. It was high time he too went to bed, but before he did so, he consumed another liqueur brandy.

Chapter Two

The Trail Ends

Monday, August 14th

Hotels in England, however bad, seldom go very far wrong with breakfast, and Mallett, fortified by a good night’s rest, for which, perhaps, he owed more to the admirable brandy of the previous evening than to the somewhat stony comfort of his bed, attacked his imported eggs and bacon next morning with his usual appetite. As he did so, his mind reverted more than once to his curious encounter with Mr. Dickinson. A garrulous, peevish old man, he reflected, with a bee in his bonnet about the hotel, and probably, if one could have got him to talk on any other subject, about everything else as well. If his conversation ran on the same gloomy lines at home, it was not very surprising that his family didn’t altogether love him. At the same time, Mallett could not but feel a certain sympathy for him. He gave the impression of a man unjustly treated by fate. It seemed wrong for any one to be so depressed as to have to confide in a chance acquaintance in the way that he had done. And when the confidence amounted almost to a threat of suicide . . . ! He shrugged his shoulders. People who contemplated such things didn’t confide their intentions, whether to chance acquaintances or to anybody else, he told himself. But at the same time, he could not altogether rid his mind of a persistent feeling of uneasiness with regard to Mr. Dickinson. The man seemed in some way haunted. Mallett’s whole training rendered him averse from relying on, or even recognizing, any suspicion that was not founded on tangible facts. Nevertheless, he had to admit to himself that his companion of the night before had left him in a vaguely disturbed frame of mind. He seemed to carry an aura of calamity about him. And Mallett, who was hardened enough to calamities of all kinds, did not like auras.

As he finished his meal, the inspector glanced round the room. The hotel was evidently not very full, for only a bare half-dozen of the tables were occupied. He looked round for Mr. Dickinson, and looked in vain. For an instant the ominous “Perhaps!” on which they had parted flashed into his mind. Then his common sense reasserted itself. The old gentleman was having his breakfast in bed, most probably—at his age he was quite entitled to it, particularly at the end of a strenuous walking tour. In any case, it was none of his business. There would be plenty of genuine problems awaiting his solution at New Scotland Yard that afternoon.

Some five minutes later, he was walking across the lounge to the reception desk with the intention of paying his bill, when he saw a white-faced chambermaid hurry down the stairs and run to the desk in front of him. There was a hasty colloquy between her and the girl clerk. The latter spoke into the house telephone, and after a few moments, during which the maid hung miserably about the lounge, looking sadly out of place (which indeed she was, at that time of the morning), the manager, swart, flabby, and irascible, came on the scene. He had a few angry words with the girl, who seemed on the verge of tears, and the pair of them disappeared up the stairs together. The clerk applied herself to the telephone, and seemed to be speaking with some urgency.

When she had finished, Mallett asked for his bill. It was some time in being prepared. The clerk seemed preoccupied and nervous. Obviously, something was not as it should be in the hotel, and once again the inspector felt an unreasoning qualm at the pit of his stomach. Once again, he told himself that whatever it was it did not concern him. Accordingly, without comment or inquiry, he settled his account, asked the hall porter (whom he found, quite irregularly, gossiping with someone from the kitchen regions) to fetch his bag down from his room, and went out to the garage for his car.

When he drove round to the front door to pick up his bag, there were two cars there that had not been there before. From the second of these, as Mallett drew up, there alighted a man in uniform. He turned to say something over his shoulder to another who was following him, looked up, and his eyes met the inspector’s. Recognition was mutual. The man in uniform was the sergeant of police in charge at the local market town. Mallett had met him a year or two before in connexion with some inquiries which had resulted in the conviction of an important “fence,” specializing in the produce of country-house burglaries. He had liked the man at the time, but just now, as he smiled and nodded, he could have wished him in Jericho.

“Mr. Mallett!” exclaimed the sergeant, coming across to him. “This is a coincidence, and no mistake! Are you here on business, sir?”

“I am here on holiday,” said the inspector, firmly. “That is, I was here. Just now I’m on my way back to London.”

The sergeant looked disappointed.

“Pity,” he said. “It would have been a comfort to have you around, sir, just in case there did turn out to be anything in this job. Not that there ever is, in this part of the world.”

“And even if there was, Sergeant,” returned Mallett, “I am on holiday, and so remain until I report at the Yard at three o’clock this afternoon.”

“Quite so, sir. Well, I’m very glad to have seen you again, sir, in any case. I must go and attend to my business now. It’ll be quite a sensation in the neighbourhood, I expect, seeing that it’s old Mr. Dickinson.”

“Oh, it is Mr. Dickinson, is it?” exclaimed the inspector, taken off his guard for once.

The sergeant paused, one foot on the doorstep of the hotel, and looked at him with renewed interest.

“So you knew Mr. Dickinson, sir?” he said.

“I met him last night for the first time in my life. What has happened to him?”

“Found dead in bed this morning. An overdose of something or other, so far as I can understand. The doctor’s up there now.”

“Poor chap!” said Mallett. Then, conscious of the sergeant’s curious gaze upon him, he added: “Look here, Sergeant, I had rather a curious talk with Mr. Dickinson last night. There’s just a possibility I might be a useful witness at the inquest. I’d better give you a statement before I go, and meanwhile—do you mind very much if I come upstairs with you, purely as a witness, mind?”

Leonard Dickinson’s room was at the end of the long corridor which ran the length of the hotel’s first floor. Facing south and east, it was now flooded with the mellow August sun. On the large, old-fashioned bed lay the body, the angularities of the wizened features softened in death, the lines of anxiety smoothed away. Mallett, looking down on the still countenance, reflected that he looked happier now than he had in life. The last line had been traced on the map, and the end was where he had desired.

The map, appropriately enough, lay on the table beside the bed, open at the section where the Hall marked the centre of the spider’s web of tracks. Also on the table, he observed, was a bottle of small white tablets, and another, similar bottle, which was empty.

The doctor was just putting away his instruments when they entered. He was young, brisk, and cocksure.

“Overdose of a sedative drug,” he remarked. “I suppose you’ll have to have those things analysed.” He nodded at the table. “But I can tell you what’s in them.” He muttered some scientific polysyllables and added: “Analyse him, too; you’ll find he’s full of it. It’s apt to be a bit dangerous, that kind of stuff. You take your dose—it doesn’t work properly—you wake up in the night, feeling a bit stupid—think, Good Lord, I never took my dose—take another—wake up again perhaps, if you’ve had a drink too much—take two or three more for luck, and you’re in a coma before you know anything about it. Easy as winking.”

Something white protruding from beneath the map caught the sergeant’s eye. It was a small card, bearing on it some writing in a firm, clear hand. Without speaking, he drew it out, read it, and held it up for Mallett to see.

The words were: We are in the power of no calamity, while Death is in our own.

Mallett nodded silently. After the doctor had gone, he said, “That’s why I thought I might be wanted as a witness.”

He glanced round the room, and then, reminding himself that this was not his case, left the sergeant to carry on until he was free to take a statement from him in due form.

When the time came for this, the sergeant, who could not bring himself to forego the rare opportunity of cross examining so great a man, had a few supplementary questions to ask. Mallett answered them good-humouredly enough. Having seen the statement completed to the other’s satisfaction, he had a question of his own to ask.

“I don’t want to waste your time, Sergeant,” he said, “but I can’t help being a bit interested in old Mr. Dickinson. He seemed rather an odd fish, to judge by the little I saw of him.”

“He was, and all that,” the other agreed heartily.

“I wish you could tell me a little about him. He said something to me last night about having been born in this place.”

“You didn’t mention that in your statement,” said the sergeant severely.

“I’m afraid not. I thought it was hardly relevant.”

“Well, perhaps it wasn’t. In any case, sir, we hardly needed your evidence for that. It’s what you might call common knowledge in these parts.”

“He was a well-known character, then?”

“Lord bless you, yes, sir! You see, the Dickinsons had this place ever since it was built, and that was near on two hundred years ago, they say.”

“But they got rid of it some time ago, surely?”

“Thirty years ago come Michaelmas—when old Mr. Dickinson died, that was.”

Mallett laughed.

“I see that memories are long in the country,” he said.

“’Tisn’t that exactly, sir,” the sergeant explained. “Mr. Leonard—the deceased, I suppose I should call him—he couldn’t bear to leave the house. He’s been here and hereabouts off and on ever since. Quite potty about the place, he was.”

“So I gathered from what he said to me.”

“Funny, wasn’t it, sir? None of the rest of the family felt that way about it. Mr. Arthur—that was his brother—made a pile of money in London and could have bought the old place back several times over, but he never bothered to. But Mr. Leonard, for all he had a wife and family of his own, couldn’t keep away from it. Well,” the sergeant concluded pointedly, “I mustn’t keep you any longer, sir.”

It was not often that Inspector Mallett had to be reminded that he was wasting his own time or anybody else’s. He was quite ashamed to discover how interested he had allowed himself to become in what was, on the face of it, the commonplace suicide of a commonplace, if eccentric, elderly gentleman. He pulled himself together, thanked the sergeant for his kindness, and left the hotel. Then he turned his car in the direction of London, and put the tragedy of poor Mr. Dickinson firmly out of his mind.

Chapter Three

Family Post-mortem

Friday, August 18th

“Typical of Leonard to want to be buried at Pendlebury! No consideration for anybody’s convenience. Typical!”

The speaker was George Dickinson, the eldest surviving brother of the deceased; the occasion was, as will have been gathered, the funeral of Leonard, and the remarks were uttered as George was climbing heavily into his car after the ceremony. He had been a stout man when his morning-coat had been made for him, ten years before. In the interval he had added an inch and a quarter to his girth, and the resulting discomfort, accentuated by the heat of the day, had put him into what was for him an unusually bad temper. His temper, it may be added, was normally a bad one. What was for him an unusually bad temper was something quite beyond the range of the average adult. It belonged rather to the type of the ungovernable rages of the three-year-old. Unfortunately, it could not be dealt with in the same way.

“In August, too! It’s really too much!” added George, sitting down heavily in the back seat, and mopping his forehead where the top hat had creased it.

“Yes, George,” said a thin submissive voice at his side.

Lucy Dickinson had been saying, “Yes, George,” for close on thirty years. If she had got tired of saying it during that time, she kept her own counsel on the subject. It was certainly the easiest thing to say, and by confining her observations to those two monosyllables she did, as she had found by experience, contrive to save a good deal of trouble. At the present moment, for example, she would have been justified in pointing out that George himself had stipulated in his will that he too should be buried in the family vault, that at the present moment he was badly crushing her new black silk dress, and that it would have been more becoming, to say the least of it, to wait until they were out of sight of the churchyard gates before lighting one of the cigars which he was now, with immense efforts, fishing out of his tail-pocket. But to have mentioned any of these things would quite certainly have meant trouble. And trouble, after thirty years of marriage to such as George, is a thing that one learns the value of avoiding.

“Well! What are you hanging about for? Drive on, man, can’t you? We don’t want to be here all day!” was George’s next observation, directed to the chauffeur, who was still standing at the door of the car.

The car, unfortunately, was a hired one, and the driver was a young man who showed no particular reverence for his temporary employer. Servants who depended on George for their livelihood soon learned the necessity of an eager obsequiousness which in George’s language was called “knowing their place.” This one merely stared with interest at the empurpled face confronting him, and remarked, “You haven’t told me where to go to yet.”

“Hampstead,” barked George. “Sixty-seven, Plane Street, Hampstead. Go down the High Street till you get to—”

“O.K.,” the chauffeur said. “I know it.” And he cut off further conversation by shutting the door rather louder than was necessary.

“Impertinent young swine,” fumed George. “They’re all like that nowadays. And what on earth made you tell Eleanor that we would go back there after the service?” he went on, rounding on Lucy. “Confound nuisance! God knows when we shall get home.” He lit his cigar as the car moved forward.

Lucy’s voice came faintly through the cloud of tobacco smoke. The smell of a cigar in a confined space always made her feel faint, but that was one of the things that dear George was apt to forget, and this was emphatically not an occasion to remind him of it.

“She asked me if we wouldn’t come, dear,” she said. “It was really rather difficult to say no. She wants all the help she can get just now, you know. I thought it was the least we could do.”

George grunted. The cigar was beginning to have its customary mollifying effect on him, and his rage with the world at large was declining to a merely average crossness.

“Well, I hope she gives us dinner, that’s all,” he said. “It’s the least she could do.”

Lucy said nothing. She had not the smallest expectation that Leonard’s widow would wish them to stay to dinner, but it would be wiser to let George discover this for himself in due course.

“But why did she pick on us?” George grumbled on. “Couldn’t she have asked any of the others?”

If Lucy had been a woman of spirit she would have retorted that the reason that Mrs. Dickinson had asked them was that she happened to be extremely fond of her, Lucy, and that George was included merely as a disagreeable but necessary appendage to her. But the wives of the Georges of this world are not women of spirit, or if they are they do not remain wives for long.

“She has asked some of the others, dear,” she said mildly. “Edward is going back with her—”

“That smarmy parson? Why on earth—”

“Well, after all, George, he is her brother. Then I think some of the nephews wished to come, too, and of course, Martin.”

“Martin?”

“Anne’s fiancé, dear. You remember, you met him at dinner when we—”

“Yes! Yes! Of course I remember perfectly well,” said George testily. “You needn’t treat me as a complete child.”

Lucy, who had done very little else for thirty years, was heroically silent. The mention of Martin presently sent George off on another tack.

“Positively indecent, those children not being at the funeral,” he said.

“Anne and Stephen, you mean?”

“Of course I mean Anne and Stephen. They’re the only children Leonard ever had, so far as I’m aware.”

“But George, they couldn’t be there. They are abroad. Eleanor wrote to us and explained—”

“Then they ought to have been got back again. It’s indecent, I tell you. I can’t see myself, if my father had died—”

But the words had suddenly jerked back to George’s mind a recollection of what had really happened when his father died, and of the nasty, unforgivable scene that he had made with his mother on the very day of the funeral. And with that memory embittering even the flavour of his admirable cigar, he was silent.

“They are in Switzerland, climbing somewhere,” Lucy went on, unaware of the reason for her husband’s abrupt silence. “Stephen only went out to join Anne there just before Leonard died. Eleanor wired and wrote, of course, but she hasn’t had any answer. You know what Stephen is on his holidays. He’ll go off for days at a time, staying in huts and places. They may not even have heard about it yet. I’m sure they would have come back at once if they had.”

“Silly young fools. I shouldn’t wonder if they’d broken their necks.”

After this charitable observation, no more was said upon the subject, and for the rest of the way to London George contented himself with explaining at great length the measures he had taken, in his own words, “to squash the newspaper snoopers” who had approached him for information about his brother’s life and sudden death, and with reviling the Press with the paucity and inadequacy of the obituary notices. That there could be any connexion between the two facts naturally did not occur to him.

Just as they were approaching Hampstead, a thought struck him.

“By the way,” he said, “d’you think Leonard left Eleanor very badly off?”

“I don’t know, George, I’m sure.”

“I was thinking, that will of Arthur’s you know. She may be a bit hard hit. You’re sure she didn’t say anything to you about it?”

“No, I’m quite certain she did not.”

“Um!” said George, turning over in his mind the disagreeable possibility that he was going to be asked for help. He decided that it would probably be best not to stay for dinner, after all.

It was certainly a full-blown family assembly. George, with his new-born fear strong within him, took as little part in it as possible, leaving it to Lucy to say the proper things to the various people who seemed to crowd the little room. These included a number of dim cousins, who had not been able to get to the funeral. Exactly what they were doing there it was difficult to say. They seemed a little uncertain on the point themselves. Martin Johnson, Anne’s fiancé, hung rather miserably about the outskirts of the family group. In the absence of Anne, his position was an awkward one. The engagement had never been made public, and officially even the dimmest of the cousins had a better right to be there than he. Mrs. Dickinson’s parson brother, Edward, on the other hand, seemed to be quite in his element. His guiding principle in life was one which he himself had happily described as “Looking on the Right Side of Things,” and his round red face shone with unction—if that is the proper word for clerical perspiration—as he exploited the situation to the full. His one regret appeared to be the unavoidable absence of his wife, laid low by a recurrence of her chronic asthma. It was a regret shared by none who knew her. Aunt Elizabeth, to her numerous nephews and nieces, was The Holy Terror—a title which was on the whole well deserved.

Mrs. Dickinson, meanwhile, sat, the melancholy queen bee in the centre of the family hive, looking at least every inch a widow. George eyed her with interest. Lucy, he supposed, would look like that some day. After all, she was younger than he was, and a better life. What would she feel like? He averted him mind from the thought and concentrated upon Eleanor. What, in her heart of hearts, did she really think of it all? It could have been no joke being married to Leonard. He felt pretty sure that Lucy would—no, damn it! we are thinking about Eleanor!—he felt morally certain that Eleanor’s widowhood was a relief to her, even if she didn’t know it yet. At the moment, she was everything that one could expect—calm, subdued, and appealingly helpless.

Presently sherry began lugubriously to circulate, accompanied by small, dusty-tasting sandwiches. Little by little conversation began to be more animated. There were even faint approximations to laughter in one corner of the room, where some of the less responsible of the cousins had forgathered. But, on the whole, the decencies were preserved, and talk remained at a low pitch, so that the sound of a taxi being driven up to the door was distinctly heard by every one in the room.

“Now, I wonder who—” said Edward, who happened to be nearest the window, peering out anxiously. “I only hope it’s not—Bless my soul, but it’s the children!”

A moment later Stephen and Anne Dickinson came into the room. They looked very much out of place in that funeral company. Except for the ice-axes and rucksacks which they had presumably just deposited in the hall, they were equipped as though Plane Street, Hampstead, were a glacier and No. 67 an Alpine refuge. Their huge iron-shot boots grated uneasily on the parquet floor, and when Anne bent to kiss her mother it became only too apparent that her breeches had been lavishly patched in the seat with some rock-resisting but alien material. From the cousins’ corner came something very like a titter.