9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

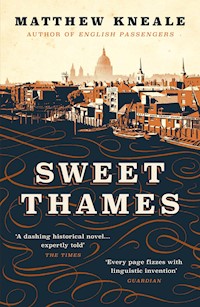

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

In the summer of 1849, cholera threatens the city and the people of London. The authorities send millions of gallons of sewage cascading into the Thames - for many Londoners the only source of drinking water. Joshua Jeavons, a young and idealistic engineer, embarks on an obsessive quest to find the cause of the epidemic. As he labours in a fog of incomprehension, his domestic life is troubled by the baffling coldness of his beautiful bride, Isobella. But when she suddenly disappears, his desperate search for her takes him to a netherworld of slum-dwellers, pickpockets and scavengers of subterranean London.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Matthew Kneale was born in London in 1960, the son and grandson of writers, and studied Modern History at Magdalen College, Oxford. He has written five novels, including English Passengers, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and won the Whitbread Book of the Year Award. His latest book is non-fiction, Rome: A History in Seven Sackings, which was a Daily Telegraph and Sunday Times book of the year. He lives in Rome with his wife and two children.

ALSO BY MATTHEW KNEALE

Fiction

Mr Foreigner

Inside Rose’s Kingdom

English Passengers

Small Crimes in an Age of Abundance

When We Were Romans

Non-fiction

An Atheist’s History of Belief

Rome: A History in Seven Sackings

First published in Great Britain in 1992 by Sinclair Stevenson.

This paperback edition published in 2018 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Matthew Kneale, 1992

The moral right of Matthew Kneale to be identified as the authorof this work has been asserted by him in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or byany means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, orotherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyrightowner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters andincidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination.Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events orlocalities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 640 9E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 641 6

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

This book is dedicated to

HENRY MAYHEW

Victorian journalist of genius,without whom it could nothave been written.

Author’s Note

Readers of this book should know that, though fiction, it is no historical fantasy. Far from it. The more strange, painful or ludicrous an incident may seem, the more closely based upon actual occurrences it is likely to be.

Note on Names

Those interested in the history of the mid-nineteenth century may notice that some fictional figures and institutions in this novel bear close resemblance to those actually existent at that time. I found this a useful means of avoiding becoming too directly tied to the daily narrative of 1849.

Thus the fictional character of Edwin Sleak-Cunningham may have more than a little in common with Mr Edwin Chadwick, important figure in the Victorian sanitary movement. The same closeness is true of the fictional Metropolitan Committee for Sewers to the Metropolitan Commission for Sewers; the fictional Association for the Promotion of Health in Cities to the Health of Towns Association; and the fictional National Council for Health to the actual Board of Health.

Chapter One

The glory of a London unobstructed by effluent. This was the vision of the future that flashed into my imagination as I stood above the sewerage outlet on the north Thames bank. Our metropolis free from noxious odours affronting the nostrils, from unsightly deposits, from the miasma cloud of gases hanging above the rooftops. I grew lightheaded at this dazzling prospect. Until I realized, surprised, that juices were stirring in my loins.

‘Thirteen inches deep here,’ Hayle, my assistant for the morning, called up from before the sewer where he stood ankle deep in the current effluent.

I noted the quantity in my field book.

‘That enough measurements yet for you, sir?’ In his voice there was a detectable note of complaint. ‘We don’t want to overdo it, do we.’

I knew the cause of his grumbling well enough; we had been at work since half past five in the morning, on this, Easter Monday, when most of London was in holiday mood, perhaps out for a spree at the Greenwich Fair. Not that this was an unusual state of affairs for me; the urgency of my task had required that every spare moment be put to good use, including – to my own shame – more than a few sabbaths.

Half past five. My lack of sleep gave the morning a dreamlike quality. Still I felt no sympathy for my servant. After all, nothing had forced him to work so early except his own eagerness to earn my shillings.

‘Mr Hayle,’ I told him, ‘if you don’t mind, I’ll be the arbiter of when we’re finished here.’ As I peered down at my notebook I was sure I detected, from the corner of my eye, quick movement of his fingers, as if he were making some obscene gesture. Looking up, however, I saw nothing except a faint smile on his lips.

‘Whatever you say, sir.’

I had never liked the fellow. More than a few times I had discerned in his manner a sarcasm, as if to work for me were beneath him. Even for a servant – a class I especially detested – there was in Hayle much ‘I know better though I will not say it clear’. He was quite a crone, having served in some lowly rank of soldiering in the war against Bonaparte, and probably it was there that he had learned to treat his masters as a snide nanny might her charge. Frequently I had discerned in him sneering. Sneering at my mere five-and-twenty years of age. Sneering that my drainage scheme for London had found no supporters in the world of engineering. Sneering at my humble background – my father had been a repairer of watches – and my having grown up into the world without Hayles of my own to direct.

But it was he who was stood in the shit.

‘Try over there,’ I suggested, watching not without satisfaction as he wobbled against the current into a deeper part, and the liquid nearly overran the top of one of his boots.

‘Mister, mister…’ The street urchin tugged at my sleeve. He had been following us for an hour or more as we toured the sewerage outlets into the river, regularly demanding a shilling. A sadly vile creature, he resembled a torn sack poorly repaired with string; string, indeed, seemed the greater part of him, holding together what remained of his rags – shiny with grime – with bulbous knots bulging about his wrists, ankles and waist. But at least, in the furtherance of his own cause of begging, he displayed a lively perseverance quite absent in Hayle.

‘I’d keep an eye on him, sir,’ the servant called up. ‘He’ll have your watch.’

‘That’s not so, mister, never so.’ The urchin’s face was wizened into resemblance more of an old man than a boy. Framing his forehead with a kind of sad exoticism was a red ‘Wide Awake’ hat, brim long since lost, so that it resembled a filthy fez. ‘I just wanted to ask a question, didn’t I. Just a question.’

I was curious. ‘And what was your question?’

‘Why’s ’e jabbing that stick into all that filth?’

It was a not unintelligent enquiry considering the source. ‘He’s measuring the depth,’ I explained.

His face screwed itself into a fist of incomprehension. ‘Wha’s he want to do that fer?’

‘So a fine new system of drainage for our city may be planned.’ I studied the lad’s face, wondering if the quickness in his eyes represented interest in my words or mere alertness for opportunities of theft. ‘We must know how much liquid pours through the sewers, you see.’

Hayle glanced up from his work. ‘Training him as your assistant, are you? You’d be better off leaving him to turn into the nat’ral grown murderer he’s intended for.’

‘You should show a little Christian faith, Hayle, rather than condemning the boy.’ I returned to the urchin. ‘What’s your name, lad?’

‘Jem.’

‘Well Jem, is our work interesting to you?’

‘Oh yes, certinly ’tis.’ The creature bolstered his reply with a kind of smile, half-toothed and hungry, the effect by no means reassuring.

‘Then you shall learn more of it.’ I glanced at Hayle, yawning extravagantly in the stream of effluent. ‘My servant here shall act as demonstrator of the methods we are using.’

The yawn abruptly died.

It had not been the best of mornings. Throughout I had been uneasy, agitated by a dream. Absurd, I reasoned, to be so alarmed by a mere imagining. One, moreover, whose subject I could not so much as remember, as all recollection had slipped from my grasp on the instant of gaining consciousness – at that quiet, early hour – eluding all effort at recapture. But still the nightmare clung to me, troubling my thoughts with its aftertaste; something of a smouldering panic, almost as if I had committed a crime.

I was dimly convinced it had involved my wife.

‘Over there, nearer towards that boat,’ Jem ordered. Hayle obeyed his new master with visible sulkiness, petulantly splashing through the flow towards the skeleton of a rotted skiff. He planted the measuring stick sharply, as if hoping to impale unsuspecting submarine vermin.

‘Twelve inches.’

The urchin peered down at him with seriousness, not at all playing a game. ‘Now do the bit with the wood.’

With a glare at the lad, Hayle held the measuring stick just above the level of the liquid, plucked a red-painted wood chip from a sack on his back, and dropped this into the flow, regarding its speed of progress past the stick’s markings while also observing the watch in the palm of his hand. ‘Two seconds and a quarter.’

‘Thank you.’ I noted the figure in my field book.

‘Wha’s’at strapped to you?’

The child had observed the case attached about my waist, and I opened it up to extract the handy portable sextant it contained. The instrument – which I had had little enough need of that day – was new and shone pleasantly.

Jem’s eyes widened. ‘Gold, is it?’

‘Listen to him,’ called out Hayle. ‘No mystery what studyin’ ’e’s bin up to.’

‘The boy’s showing no more than a healthy interest in the science of the device,’ I retorted. I held the object before the creature, without actually releasing it into his hands. ‘It’s brass.’

He touched it with his finger, leaving a small greasy smudge.

‘Will you remember what you’ve learned today?’ I asked him.

‘Oh yes, mister.’

‘Then you shall have a reward.’ I replaced the sextant in its case and took from my pocket a shilling. The lad stared, clutched towards it, then, when I released the coin, darted back some yards – doubtless lest I change my mind – and despatched it into some recess of his rags with the swiftness of one well alive to the danger of letting silver see the light of day an instant too long. Without a word he scampered away along the river.

‘Waste of good money.’ Hayle looked put out. He would have liked the shilling for himself.

‘Don’t be so mean-spirited,’ I told him. ‘Probably you are wearied and agitated by your exertions – you’re no longer so young, after all – and this has made you so.’ I glanced at the columns of figures in my field book; ample now. There was no sense in detaining the servant longer. ‘Pack up the things and that’ll be enough for today.’

He trudged from the sewer to a street handpump close behind, where he began cleansing his boots and the measuring stick, subjecting them to angry belches of water.

The charitable exercise had, of course, been partly to taunt Hayle for his sneerings, but not for that purpose alone. I had also been fired by a genuine hope that the lad would somehow be won over to the importance of sanitary change. It was a notion very much in the spirit of my passions of that time; I was caught by an urgent wish that all – however lacking in usefulness they might appear – might be won to the brave cause of drainage reform.

It was still only quarter past eleven. I had promised my wife I would be home by one o’clock, as she had planned a small luncheon party; though I had little fondness for the guests invited, it was so unusual for her to suggest such an event nowadays that I felt I should give every encouragement. Who knew, perhaps it might help set her upon a brighter course.

An hour and three quarters. It was quite an amount of time. I stared out across the river, pondering what useful task I might set myself; one that would not take me far from my route back to Pimlico, yet would also be attainable without the help of a servant.

It was low tide and beyond the marker-less mire of Thames mud the river seemed little more than a ditch in the ooze. A black Thames barge crept warily along its surface, heavy brown sail flapping in the light breeze. To the west four figures were advancing along the water’s edge, silhouetted dark against the grey sheen and, idly watching, I studied their progress nearer, until they were close enough to observe in detail.

A strange party they were. Each carried a pole that was taller than himself, with a hoe attached to the end, and had a sack strapped to his back. All were shoeless, and wore similar coats: long and greasy, with objects dangling from the breasts that seemed to be lanterns. Lanterns? My interest grew as I realized they were not passing by, but seemed to be making their way towards the very sewer entrance we had just investigated. For what possible reason? They had reached the place where Hayle had stood only a short while earlier, when the tallest chanced to glance up. Seeing me, he let out a cry.

‘Spy.’

In an instant they were off, bare feet producing a faint squelching in the mud as they dashed away eastwards, towards Wapping.

I turned to ask Hayle what manner of men they could possibly be. But he had already gone.

Foreign sunlight shines in between the slats of the shutters, bright and hot even in the late afternoon. Through the distance of miles and two full years I see that London summer in a remembrance strangely focused. It is as if it were not me but a different man who lived through those months of fearsome discoveries. I can almost see him thus, as a soul separate from myself.

There. Still puzzled by the sight of the four men with poles, he steps forward to cross the Strand, watching for horse dung, picking his way between the omnibuses and coal wagons that creak and crunch and raise up clouds of street dust. Joshua Jeavons dodging a brewer’s dray, eyes alert, keen, seeing no impediments to his progress that he cannot swiftly overcome. Joshua Jeavons, his young man’s beard short and pointing sharply ahead from his chin, pulling forward, as if in representation of some greater propellant within. Joshua Jeavons, now striding past a newcomer from the country who is halted by the never-still hooves and wheels before him. Joshua Jeavons, pressing on past the fellow. Joshua Jeavons possessed by strange eagerness, as one set on outpacing an electric storm.

The task I had chosen myself had been to inspect the possible site of one of the Effluent Transformational Depositories. According to my scheme these would be established all across the metropolis at locations of low height, so the fluids would flow into them by gravitational process. The valuable elements would then be removed from the rest by sedimentary separation, and drawn out by steam engine, to be transported away in specially designed carts to rural areas, where they would be sold – at a wonderful profit – to farmers.

The spot was in an area of small roads to the east of Covent Garden. It had seemed simple enough to locate when I sat in my study inspecting my map of the metropolis; so much so that I had not troubled to bring the bulky plan with me. Once in the district, however, the streets proved quite a maze, and for some time I wandered, unhappily aware of the roar of Strand traffic – echoing mischievously from the high brick façades so it was hard to say from exactly whence it came – growing fainter behind me, telling that I was venturing even further from my quarry.

I paused to ask the way of a clean-chinned fellow selling apples, who pointed me in a direction quite unexpected. ‘Through that way, mister, though it’s a bit of a step from ’ere.’

Onward I hurried, through narrowing lanes, urchins emerging from alley-ways, yelling and pestering until I scattered them with a raised hand. This was no place for the unwary. Even at this hour the bricks of the walls seemed to murmur faint warnings, and my glance darted ahead, alert for some over-swift movement, perhaps a flash of metal. Indeed, I pondered, such streets – stench and decay rising up from the defective sewers they were built upon – were an aching instance of the need for improving work by engineers such as myself. The effluential evil should be plucked out. Nor only here; half the metropolis required urgent attention. A giant cleansing, a renewal. That the nation might embark upon a new and sanitary road.

I rounded the corner and, with a start, found myself in a chasm-like alley that seemed familiar. No, there was no mistaking it; the clean-chinned apple salesman had utterly misdirected me, whether by accident or from malicious design. I quietly cursed the fellow, glancing up at the shabby houses that seemed to be elbowing one another for space, as a parade of drunken giants, divided by a passage so narrow that wooden rails stretched across from window to window opposite, from which washing flapped idly in the gloom.

I was close to the Seven Dials, fifty yards or so from the rookery of St Giles, a nest of all manner of criminality and vice. My chosen site for the Effluent Depository had, of course, been left far behind, and I reluctantly accepted that I should not attempt retracing my steps; after all, I might only become lost again.

‘I’ll give you a good time sir, nice gent like yourself.’ The speaker was coarse-featured, her face and neck red from exposure to the weather. She clutched at me with her grimy hands and I warned her off with a shout. Other voices murmured their entreaties.

‘Any way you like, mister.’

‘Just five shillings.’

I was surprised to see so many at such an early hour; usually they gathered only as the light faded, taking their places in doorways as the abusive children seeped away. Perhaps they hoped that, this being a holiday, they might win extra trade.

‘Katie’ll give you a good one, like you’ve never had.’ This last was quite pretty in a blank, drink-dazed way. Seeing me glance at her, she stepped out. ‘Just six bob to you. Yer won’t never regret it. Time of your life, you’ll have.’

‘Is that so?’

‘Come and find out, why don’t you, eh?’ She took my hand and guided it nearer. The material of her dress was coarse, oily to touch, but the breast within was warm and soft.

It was hardly the moment. Unless, perhaps… ‘You have some place near here?’

‘’Course. Katie ’as ’er own room, she does. Just six bob. Five and six if you’ll get us a brandy first.’

I looked at her hard. ‘You’ll be wasting your time if you try any cheating.’ In the past I had suffered several attempts to rifle my pockets, while once, in a vile den in Borough that I should never have visited, a ruffian burst in and tried to steal my trousers. ‘I am not one to be taken in.’

‘Who said anything ’bout that? You’s safe enough with Katie.’

The poor creature was desperate for drink and so, warning her of my hurry, I took her to a nearby gin palace; a loud, gaudy place, all mirrors on the walls and gaslight thrown here and back in quivering reflection. She drank the spirit in quick swigs, and we moved on to her lodging room. Naked of her cheap clothes she was much improved, her body a little skinny perhaps, and hair lank and in need of a wash, but her face pleasing. I lay down beside her on the bed, touched her between the thighs and felt a greeting warm moistness. The brandy seemed to have had a beneficial effect and she displayed a liveliness rare in her profession.

‘Just you lie back,’ she urged. ‘Katie’ll give this gent sich a time as ’e’s never ’ad.’

But in my enthusiasm I toppled her on to her back, eliciting a shriek of laughter.

You must understand that the drainage of the metropolis was not a mere question of work, of professional advancement. It was as a mission to me. A passion.

I had long been concerned with the question of sanitary reform. The middle and later ’forties were years when all the nation was growing outraged at the state of its cities, and great public organizations were springing into being; including the Society for the Cleansing of the Poor and, larger still, the Association for the Promotion of Health in Cities. In the company of so many other angry Londoners I joined this last, attending its public assemblies – as busy as Ladbroke Grove race meetings – signing petitions, witnessing discussions and cheering the speeches of its leaders, instilled with the enthusiasm all about me.

It was not long before the Association’s pressure bore fruit. A reluctant Parliament was goaded into action, and a new authority created: the Metropolitan Committee for Sewers. Its ranks abounded with fine names – even two lords – and men well versed in the great problems to be tackled, including, as leader, none other than Edwin Sleak-Cunningham, hero of the sanitary movement. A new public body to fill us all with hope. London, greatest city of the planet, vaster than Paris, even than far-away Pekin, to be wondrously free of effluent.

It was after the Committee had been established – about the time of my own marriage – that my views began their alteration. Until then I had, like most other members of the Association, been little more than a concerned spectator, shouting for the cause he favours. Then, gradually – and for reasons I was not certain of myself – I found the issue had become something altogether closer to me; an open wound.

Thus, when I walked through London streets I found myself fiercely aware of the vile smells rising up from gulley holes, of evil deposits piled up in the gutters. Not that these were new phenomena, far from it. Rather it was that I had grown more sensitive to such horrors, until they were a constant affront. I found myself glancing up to the sky with concern, watching for the miasma; the cloud of effluvia gases hanging above the buildings of London, disgorging sickness. I began to discern it quite clearly, and see its shifting evil.

The new Committee produced its first public announcement: it called for rival schemes for the drainage of the metropolis to be drawn up, by an engineer or other member of the public interested. Projects would have to be submitted within five months, after which they would be judged by the Committee members, that one could be chosen and made into reality.

How could I not rise to meet such a challenge? Setting my engineer’s training to work, I pondered and planned, then finally devised the notion of Effluent Transformational Depositories; a system quite original and, I confidently believed, utterly answering the needs of the matter. Indeed, I saw it as little less than a double salvation for the metropolis. Not only would the streets be cleansed – the wound healed – but the sale of the effluent to farmers would bring in a substantial income, reducing the burden upon ratepayers, and so adding to the wealth of the citizenry.

Then followed disappointment. My father-in-law and also employer, Augustus Moynihan, refused to take up my scheme for his engineering company, claiming drainage was too much of a departure from his earlier projects, which were most of them railways. Other companies then also proved reluctant, no doubt influenced by the thought that Moynihan – my own relative – had chosen to reject the idea. A great setback. Still I remained undaunted. I had faith in the scheme and determined, if necessary, to work quite alone. I would carry out my own researches in what little free time I could secure for myself, hiring servants such as Hayle from my father-in-law’s company, while, for my livelihood, I would continue also to work there. A hard regime, perhaps, but one well justified.

The honourable profession of engineer. That was my vocation, my training, and still it is. If my writing seems sometimes simple I make no apologies. Never was I taught the art of words in the way others show such clever skill; to devise sentences that meander back and forth in interwoven clauses until, without a halt, they have occupied a page and a half and, along the road, twisted meanings beyond recognition.

Nor would I wish it so. Why embellish events when they require no such doctoring? I seek only to set them down truthfully, to call them into life, that they may exhibit their own natural strangeness. I will not cosify that hot summer; if my own character and actions are not always pleasing, so be it. Only by setting down the harshest of details may I hope to comprehend them better. And perhaps exorcize them from my soul.

And what is my story? Most of all it is of the search for my wife. And where I eventually found her.

My first sight upon waking was Katie lying on the bed, watching me with dim curiosity. She was aligned exactly towards me, so that, as I raised my head, her buttocks seemed almost to emerge from the lank curls of her hair, while her feet – kicking the air with vague restlessness – stretched up behind them in the shape of a Vee, toes probing the air.

‘How long have I been asleep?’ I did not wait for an answer, but reached for my watch: It was past one o’clock. ‘Why didn’t you wake me?’

‘Seemed a shame when you looked so peaceful.’ She rolled upon her side, as a cat exposing its belly, amused by my panic. ‘An’ there was nobody waitin’ his turn outside.’

It was hardly her fault. I tugged at my trousers, angry at my own weakness. To have fallen asleep at such a time.

She rested her hand on her chin. ‘What’s yer hurry? Why don’t you stay a bit.’ Eyes watching me, she slipped her hand behind her back until her fingers reemerged through the crack between her thighs, where they waved in a kind of greeting. ‘Might be nice.’

‘No, I must go.’

She shrugged. ‘Well, come visit Katie again, won’t yer? It’s nice to see a gent for a change. Don’t get many gents round here, yer don’t.’

I dropped the coins on the bed.

‘What’s yer name, anyway?’

My patience was leaving me. ‘Does it matter?’

‘Only asked, didn’t I.’ She drew her knees up to her chin, encircling them with her arms, as if to reclaim her parts. ‘I told you mine happy enough.’

I picked up my hat. ‘Henry Aldwych.’

She seemed pleased with the false name, unlikely sounding though it was, and released her legs, stretching them out before her. ‘’Enry,’ she repeated to herself. ‘Come again soon then, will yer, ’Enry?’ She let out a laugh at her own remark which pealed behind me as I left. ‘Come again.’

I hurried down the stairs, pushing loose flaps of shirt into the band of my trousers as I went. If I could find a cab on the Charing Cross Road I might not be so late. And I would be able to tidy myself up a touch on the way. If I could find one…

‘Want a good time, mister?’

‘Just six bob to yer.’

Emptied of passion as I was, the women’s harsh, grimly routine voices awoke in me a shame. To have allowed myself to be led by base urges, no better than an animal. And in such a place; a threatening slum. The troubles I had brought upon my own head seemed only too just. I should even consider myself lucky not to have brought some greater catastrophe upon myself; robbery and permanent injury, perhaps, with the further shame of having to be rescued from such a den, and explain. Not for the first time I determined never again to fall to such lowness.

A smell of effluent hung in the air, rising up from some badly built drain, seemingly stronger since my unintended arrival in the district. I sensed the odours as in some way feeding the criminality above, acting as a fertilizer of evil, luring me to misadventure. I held my handkerchief to my nose.

‘Got a cold, ’ave yer love? I’ll warm yer up.’

It was then, of all moments, that I remembered my dream.

The man had been greyly anonymous, a mere enemy form. My wife, by contrast, had been clearly detailed, clothed – puzzlingly – in her finest Sunday dress. Her face I could not see as it was buried against his chest; she entwined him as a creeper about a tree, absorbing the very flesh.

The touch of the knife in my fingers.

‘Only six bob to you.’ The woman had misread my hesitation as interest and stepped forward towards me. ‘Time of yer life, I’ll give yer.’ When I walked on she clutched at my coat-tails until I shooed her away.

Of course I knew the inspiration for the nightmare clear enough. The letter I had been sent.

*

Our rented home was in Lark Road, a street close by the new district of Pimlico, that giant construction yard of fine tall buildings still in their making. Lark Road, by contrast, was neither modern in design nor grand in proportion, but a survival from the age of Queen Anne, the houses it contained most dull and old-fashioned – sad to say we could afford no better – with rooms that were modest to the point of pokiness.

Our home was, at least, wonderfully clean. My wife kept it so, with fireplaces swept, tables polished, and windows freshly wiped; free of all but the most lately arrived film of soot. It was her fancy to do so. In fact more; it was her passion. She had evidently been working particularly hard in preparation for the luncheon party, and as I walked into the parlour the room seemed to gleam.

‘Joshua, at last. We were beginning to wonder if you’d fallen down one of those awful drains.’ Though she uttered the words lightly enough, her eyes showed her relief, as well as something like anger at the distress I had caused her. She hated my being late, as it would never fail to make her fear some accident had befallen me.

‘I’m so sorry. I quite lost track of time. You shouldn’t have waited.’

The two guests, Gideon and Felicia Lewis – brother and sister – watched me with vague curiosity.

‘We didn’t wait.’ Though she smiled, my wife spoke with sharpness, still angry. ‘The dinner’s not yet ready.’

Isobella Jeavons, turning with a smile to attend to her guests, a sight to behold before me, elegant hostess of a London luncheon party – formal occasions seemed to call forth all her grace and composure – filling me with pride, and a sense of my own clumsiness. Also something like trepidation. It was a rarity to see her so animated, and always I wondered how long it would last, before dissolving into something more brittle.

That day, of course, I had also other concerns. I hung back from kissing her for fear that, were I to venture so near, she might detect through the fabric of my clothes the odours of my recent lust.

The mere thought of it...

‘I hope you’ll excuse me if I change from my work clothes.’

Passing through the hallway I caught a glimpse through the kitchen doorway of the bulky form of Miss Symes, our servant, wrestling with a joint of lamb. Grasping it with one padded hand, she was endeavouring to poke the thing with a long knife, testily, as if to be fully sure it was dead. The meat was pale, and looked still only half-cooked. A relief as it reduced my embarrassment at being late. The bathroom afforded me further encouragement; the mirror revealed my efforts to tidy myself in the cab had been more successful than I had feared. Who knew, perhaps I might, after all, survive the day without suffering disaster.

What my wife saw in the Lewises I could not comprehend. They were a plain pair. Gideon seemed to be lacking in weightiness, troublingly so, his head forever bobbing about, as if he might at any moment quite float adrift from the ground, in the manner of some escaped hot-air balloon. Felicia was more firmly anchored; fiercely correct – so covered up with clothes that scarcely a speck of hand or throat showed – with something of the manner of a trap, ready to spring shut upon the unwary. And yet my wife attended Felicia’s bible gatherings with regularity, and invited her and Gideon to our home, in determined preference to other, far less odious acquaintances. When I once asked about the matter, she grew annoyed.

‘Joshua, I’m most fond of the Lewises. You mustn’t criticize them so. It’s not fair of you.’

And yet… I watched as, the meal having been so delayed, she embarked on passing round a bowl of burnt almonds. First to Felicia, then – more surprisingly – to myself. Finally she took one with her own delicate fingers, and placed the remainder on the side table. Gideon, abandoned, made a poor attempt to smile.

‘Those do look delicious.’

Isobella’s cry of dismay was almost too rich. ‘Oh Mr Lewis, how could I?’ Had I not known of her devotion to them both, I might have imagined she had deliberately contrived to make the fellow look foolish.

She sat back in her chair, feet gathered up from the ground, pressing tight against one another, in a way that made her, all at once, look youthful, even childlike. Why not indeed, when she had barely reached her nineteenth birthday; fully seven years younger than myself. At times she could possess an innocence that quite stole my breath from me; that made me feel as much a parent to her as a husband.

What kind of person could send such a letter, filled with poison towards a soul of such simple purity? The writing had been quite unfamiliar, formed in a style resembling printed script, no doubt to better disguise the hand.

SOME HUSBANDS SHOULD KEEP ACLOSE WATCH ON THEIR WIVES

Someone from work, jealous of my having married the daughter of Augustus Moynihan, owner of the company? It was the most likely possibility, and yet no candidate sprang to mind; among the faces were none I could imagine desiring to carry out an act of such malice.

Several times I had intended discussing the matter with Isobella, but then had found myself unable. How could I? It would be like teaching brothel slang to a saint.

Brothel slang to a saint. After this interlude of years, I wonder if there was not, perhaps, also a second reason. One protective not of her but myself; a motive barely glimpsed. Fear of what I might discover.

‘It’s certainly a most colourful room.’ Felicia uttered the words in a tone of disapproval, correcting her brother’s earlier enthusiasm. The conversation had hobbled and stumbled as a one-legged man on stony ground, until plucked up by Gideon – a touch desperately – and deposited on the subject of ‘things on the mantelpiece’, which he endeavoured to praise. His sister’s puritanical nature evidently saw little that was worthy of congratulation.

‘A most bright arrangement,’ she continued, in the manner of one who has stumbled upon a minor colliery disaster.

Gideon glanced awkwardly at the carpet.

‘We like it so,’ I answered with firmness, looking Felicia straight in the eye with a smile. How dare she. I was most proud of our parlour – our display to the world – though we rarely ventured thither except when we had guests. I glanced about at the furnishings, regarding them with a sense of rediscovery.

It was a finely modern sight. The dark green wallpaper and fiercely scarlet French stool were sufficiently strong of colour as to be little affected by accretions of soot from the air and fireplace, while our most valued possessions – the majority wedding gifts, as we had never been in the position to go purchasing pretty things – were cunningly protected against the ravages of dust. Thus the tiny stuffed tropical birds of all colours of the rainbow – nestling on branches with astonishing realism, as if each had set down from flight just that instant for a short rest – were encased in a smooth dome of glass. Likewise encapsulated in two smaller and matching domes were our busts of Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort Albert, executed with suitable dignity of expression, and lodged proudly on the piano.

Probably Felicia was offended that the legs of the chairs and tables were not modestly concealed behind hangings. Certainly she appeared annoyed by something; from the first she had been in a mood of unusual sourness – even by her own severe standards – darting withering glances at her brother, and also at Isobella. How could my wife endure such people?

My ruminations were interrupted by the arrival of Miss Symes, without knocking, as was her way. ‘About that ham, missus, that you thought of havin’ on the side. There’s only the two slices left, see.’

She was a weightily formed woman, built of the kind of flesh that seems always faintly reverberating, as if containing bags of thickened liquid. Persons thus shaped are held in the popular imagination to be of a warm-hearted disposition, but Miss Symes was proof of the weakness of such theories. She was sulky and complaintive, also lazy, and, I was sure, of limitless appetite, as our larder seemed constantly in need of replenishment. We had chosen her only for one reason: she was cheap. Even then we could afford her for only seventeen days in a month, sharing her with the family of a Highbury legal clerk. She had insisted on board, though the arrangement was only part-week, and slept in a room hardly larger than a cupboard, into which it was a mystery to me how she managed to fit herself.

Despite her inexpensiveness, her ill-manners had several times led me to suggest to my wife that we try and find somebody else. Isobella had surprised me with her insistence that the woman stay. The only explanation I could see was that Miss Symes’s indolence gave her unrestrained opportunity to throw herself into her passion – so admirable – of domestic activity; cleaning and polishing every object until it shone.

‘There were a good eight slices of the ham last night,’ I insisted. ‘Where’s it all gone?’

Miss Symes put on a look of studied indifference. ‘Must’ve just went, mustn’t it sir.’

‘It’s of no matter,’ my wife suggested, before I had time to remark further on the matter. ‘We’re better off without it, I’m sure.’

‘Very good, ma’am.’ As Miss Symes manoeuvred her person back through the doorway there was a scrabbling about her feet and Pericles, my wife’s terrier, scuttled into the room.

It had been my idea that she should have a pet, so she would have a companion to brighten up her hours in the house. Indeed, in some ways the dog might have been viewed as a success; Isobella took to him from the first, embracing him whenever he appeared and inventing all manner of affectionate names for him: ‘Peridog’, ‘King Peri’, ‘Little Naughty’ and many others.

I, however, found myself unable to stifle a growing loathing for the creature. There was something vile about the way he would lick her face so keenly, even her very lips, how he nuzzled the cloth of her dress just where it thinly contained the soft roundness of her bosom. He must have somehow discerned my dislike for him – animals can be surprisingly sensitive to human feelings towards them – for he soon regarded me as his foe, yapping at me with his small dog bark whenever the opportunity arose, growling, and occasionally attempting to nip my ankle with his teeth. Isobella would reprimand him, but without great severity, still referring to him as ‘Little Dog’ or ‘Perikins’. I sometimes retaliated when the creature was out of view of his mistress, with discreet kicks to his person.

‘Peri, Peri, Peri the Bad, where have you been?’ she almost sang to him as she plucked him from the ground, and allowed him to lunge with his mouth towards her ear. ‘Were you playing in the kitchen?’

With small-animal impatience he sprang from her grasp and darted across the room, pausing to stare at Gideon, who reached out, with the idea of patting his head. ‘Hello my fine little fellow.’

The dog growled audibly, then snapped, jaws not quite reaching the proffered fingers.

‘Pericles,’ my wife scolded him, without great feeling. ‘How bad he is.’

‘He’s charming.’ Gideon manufactured a smile.

The creature had already moved onwards, now leaping up at the edge of the table, overhanging which was my wife’s embroidery. Embroidering was a hobby of hers, and one which she pursued with the same restless perfectionism that she exhibited towards the domestic arrangements of the house; this was already the tenth such creation in eight months of our marriage; an astonishing pace of production. The nine so far completed – now framed and displayed on the walls, fast diminishing in unused space – all took the same form; of a biblical quotation framed by flowers. This latest had not progressed far, and as yet read only, DOEST NOT…

‘Little dog, really now.’ She got up from her seat to reclaim the animal, grasping him firmly on her lap.

It was then I saw the knife.

To look at, it was hardly remarkable; a slim piece, more ornamental letter-opener than cutting blade, with a delicate mother-of-pearl handle. It was on the table among Isobella’s embroidery things, and she must have been using it to snap the threads cleanly. Probably it had lain about the house since the day of our marriage, and I had never given it a thought in all that time. Until it had featured in my dream.

In my distraction I had, I realized, been staring directly at Gideon’s weak chin for some moments. The conversation having moved onwards from the parlour to the question of work, he had embarked on an interminable description of the duties of an architect of church buildings; his own profession.

‘We have the chance to look back over church styles of all ages and nations, take the best from each, and so create such a design that none other will ever be needed again. Think of it. An epilogue to the whole great volume of ecclesiastical architecture. Responsibility indeed.’ He paused, regarding me kindly, appearing to assume my blank glare had told of a fascination with his words.

A thump outside the door warned of Miss Symes’s return. ‘It’s ready now, missus.’

‘Thank you, Miss Symes.’

An idea came to me. As the others rose from their places I lingered, allowing them to chatter their way out of the room before me. Then, when I could hear all had made their way across the hall and to the dining-room, I plucked up the knife. The very touch of the metal was troubling; almost as something so cold that it threatens to stick fast to one’s skin.

I saw a pair of eyes staring at me. Pericles, lodged beneath the table, uttered a growl. A neat tap to his backside with my foot elicited a yelp and caused him to scurry from the room.

‘Is something wrong?’ called out my wife.

‘Just coming.’ There was no time to do more than open the front door – as noiselessly as I was able – and hurl the thing into the street slop dirt, grinding it in deeper with the toe of my boot.

At last the Lewises had left us. I closed the door and we made our way back into the house. Miss Symes was clearing plates and such from the dining-room to the kitchen – sporadic thumps and crashes reverberating through the house told of her labours – and so we took refuge in the parlour.

What a relief that they had gone. Only my unwillingness to spoil an occasion into which my wife had invested such effort had prevented my directing some sharp remarks to the two guests. Gideon, in particular, had been infuriating.

The fellow was, it seemed, a keen amateur painter and, during the roast lamb, had embarked on an account – both dull and fairly lengthy – of the lives of Italian Renaissance masters; while the plates of the rest of us grew empty, his remained all but untouched, and the dessert was greatly delayed. Worse was the man’s smugness. He talked of Guido Reni and Michelangelo as if both were his personal acquaintances, and described their works with the knowingness a school-ma’am might employ when detailing the efforts of her more able infants, beaming all the while – doubtless at the pleasure he imagined he was affording his hosts.

Isobella perched herself upon the French stool and picked up her embroidery that she might resume her work. She seemed not to notice the knife’s absence. For my part, the panic I had felt earlier seemed now painfully absurd: the delusions of a man weakened by tiredness and hunger. I had half a mind to retrieve the object and replace it, at some moment when my wife was busy elsewhere in the house.

Where to sit? Normally I would have chosen one of the upright chairs. Perhaps it was my pleasure at the Lewises’ departure that persuaded me otherwise, or the two glasses of wine I had had with the luncheon. Or the bright smile I had watched earlier on my wife’s face. Whatever the reason, I sat down beside her on the French stool. It was quite a squeeze, true enough, but still her response distressed me; she fairly jumped, edging away so we were not touching.

One action, one instant, and so much seemed changed. Already I could sense the quiet – that quiet I knew so well – beginning to descend. Speak before it could encircle us both. Say anything.

‘The apple and meringue pudding was most tasty. Did you make it yourself?’

‘I did.’ She did not so much as look up from her work. Though I could not see her eyes I knew, from the very tone of her voice, how they would be changed; animation vanished. Her lips, too, would be altered; taut, as if unwilling to form words. So often it was thus. She resented my absence – complaining of my long hours of work – and yet my presence in the house seemed to make her hardly less uneasy. And of course…

The busts of Queen Victoria and Albert glowered down from the piano, as if saddened by the scene before them.

‘I thought it must have been yours. Much too good for anything of Miss Symes.’ I struggled on against the hush. ‘I’m sure I detected a small tot of rum.’

‘I put in a couple of teaspoonfuls.’

Still not so much as a glance. It was all the more galling after her bright cheerfulness during the meal.

Did she prefer the company of the Lewises to my own? I wanted to pluck her up from the French stool, to stir her up – as some mixture left too long, in which the worst has floated to the surface – to shake her in the air, until the brittle silence was gone.

If only there were something…

Then I remembered the advertisement I had seen in The Times a few days earlier.

Why not? An expedition might do much to blow away the staleness. At least I should try. I made my way up to my study to seek the edition in which it had been.

MONSIEUR TOULON’S CONCERTS MONSTRES

A third Concert Monstre and musical ballet, in the style and scale for which M Pierre Toulon is so justly renowned, to be performed on Easter Monday at the Surrey Zoological Gardens. Programme entirely changed from M Toulon’s great five-hour concert of 1847, held before an audience of 12,000 persons. Meyerbeer’s music from the Camp of Silesia to be played for the first time in this country. M Toulon’s famous Corps of Dwarves to perform a ballet d’action entitled Pompey and the Deserter. Also M Toulon’s own arrangement of The Grand Triumphal March of Julius Caesar, complete with Double Orchestra, Four Military Bands, and Roman trumpets. Finally M Toulon’s own rendering of God Save the Queen, each bar being marked by the report of an eighteen pounder cannon. Admission only…

Just the thing. I hurried down to the parlour. ‘Come along, my dear. We’re going out.’

She frowned. ‘Whatever d’you mean?’

‘Just what I said. It’s Easter, half London is enjoying the holiday, so why not us too?’

Though she protested at first, she seemed not altogether displeased to find herself in an omnibus, streets flashing by outside. My spirits began to rise.

Perhaps it had been just such a notion that had been required all along. For all these months. I simply had not thought to try.

The concert was quite as popular as Monsieur Toulon’s previous visit of two years before, judging by the throng of metropolitan citizenry we found gathered in Kennington, joining the queue to the gardens. Once inside, ambling with the crowd past grottoes, classical statues, an ornamental lake, the sight of such a multitude of excited souls took me back to my time as a follower of the Association for the Promotion of Health in Cities. Splendid days.

Best of all, the liveliness of atmosphere seemed to have infected Isobella, causing the smile of lunch time to return to her face. Success. And who knew where it might end.

‘But it’s lovely. How is it I’ve never been here before?’ She paused, detaining our progress with an outstretched hand, her expression one of almost childlike intensity as she listened. ‘What are those cries?’

‘The animals.’ We were approaching the seats – a veritable ocean of them, enough for an entire army, freshly returned from some Easter battle – behind which rose up the circular glass building that contained the zoo’s creatures. I had briefly visited the place some years previously, and inspected the collection – not a poor one – of lions, camels, monkeys, bears, parrots and other tropical birds, as well as a rather scrawny giraffe, and a single giant tortoise on which small children were invited to ride for a small sum.

‘But can’t we see them? Perhaps after the concert is finished?’

‘If the animal house is still open to the public at such an hour, then certainly.’ Though most doubtful it would be, I was unwilling to risk forfeiting my wife’s newly re-found good humour.

I had bought good seats, despite the extra expense, and our places were close to the front, from where we had an excellent view of the conductor, Monsieur Toulon, as he stepped upon the rostrum. Bespectacled, and with a hairless dome of a head, he was surprisingly clerk-like in appearance for one responsible for so giant an event, and with the huge assembly of players ranged behind, he seemed quite a speck. I glanced up at the sky; though the day was not a cold one there was a stiff breeze and ranks of clouds were chasing each other across the sky, eastwards towards Greenwich. Brave indeed to hold an outdoor event at so early a season.

Isobella seemed to read my thoughts. ‘I hope it won’t rain’

‘At least we have the umbrella.’

The concert began splendidly, with The Grand March of Julius Caesar, a finely furious piece. To be seated before the whole ensemble of double orchestra, four military bands and twenty Roman trumpets – strange instruments that produced a sound not unlike a donkey’s braying much amplified – was as being perched before a kind of musical hurricane.