Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

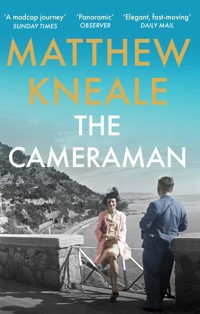

Former cinema camera director Julius Sewell journeys across Europe with his family to his sister's wedding in Rome. But this will be an unusual road trip. For one thing, Julius has been in an institution and has only just been released to travel. And then there is his family. This is Easter 1934 and Julius' stepfather and mother are keen members of Oswald Mosley's new party, the British Union of Fascists. One of Julius' half-sisters is in studying in Munich, where she dreams of meeting meet her idol, Adolf Hitler. Another half-sister is a member of the British Communist Party, and is determined to wreck the approaching wedding, because the groom is a rising figure in Italy's Fascist regime. As the family motors south, to Paris, across Nazi Germany - taking in a bus tour to Dachau concentration camp - and through Mussolini's Italy to Rome, gathering relatives and a stray dog along the way, Julius' mental stability will be put sorely to the test, as will be the sanity of his relatives.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 323

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Matthew Kneale

FICTION

Mr Foreigner

Inside Rose’s Kingdom

English Passengers

Small Crimes in an Age of Abundance

When We Were Romans

Sweet Thames

Pilgrims

NON-FICTION

An Atheist’s History of Belief

Rome: A History in Seven Sackings

The Rome Plague Diaries:

Lockdown Life in the Eternal City

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Matthew Kneale, 2023

The moral right of Matthew Kneale to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 899 2

EBook ISBN: 978 1 83895 900 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Shannon

One

Julius Sewell’s first clue that he might be about to escape came when Orderly Reese made his odd remark. Chilly in his nakedness and his head still bleary from last night’s dose of jungle juice, Julius queued for his bath: a gaunt-faced figure with hair that sprouted up from his scalp like blades of ginger grass. The man ahead of him was known for his fear of getting wet. This’ll be noisy, Julius thought, and sure enough when the other was led forward the air became filled with cries. Put your fingers in your ears. There – that’s better. Have a read of the bath rules. IN PREPARING A BATH, THE COLD WATER MUST BE TURNED ON FIRST . . . THE BATH KEY IS NEVER TO REMAIN ON THE TAP AND IS NEVER TO BE TRUSTED TO A PATIENT . . .

The shouting stopped, the man re-emerged, still quivering under his towel, and it was Julius’ turn to step into the bathroom, with its long row of tubs and their occupants. I wish they’d fill it a bit higher. It’s hardly deep enough to cover my balls. Julius glanced down at the spider of marks on the lower right side of his gut. He could just make out the neat, pale line from his appendix removal, almost lost beneath the other, more recent, purple scars. He reached out with his finger. I hardly feel them now.

And that was when Orderly Reese came over. ‘Be sure to say hello from me to all the stars, won’t you, Pictures? Say hello to Gracie Fields.’

‘I will.’ By the time the words had sunk in, Orderly Reese had gone. What did he mean by that?

His bath over, Julius dried himself and returned to the ward, with its high windows, through which bright sunlight poured. His clothes were waiting on his bed. This shirt looks all right. And I know these flannels. I wore them just a couple of weeks ago and they fitted me fine. Much better than the pair I had last, which hardly reached down below my knees. See? Today will be a good day. Then Orderly Reese’s words came back, tempting him. I’m sure he was just making a joke, like all the orderlies do. Though I’ve told them a dozen times that I never once met Gracie Fields. Most patients in the Mid-Wales Hospital were from local farms so it was inevitable that Julius, who had worked as a film cameraman in London, would be seen as exotic – hence his nickname, Pictures. But what Orderly Reese said wasn’t really funny. He’s the serious one. The other orderlies are always making jokes but not him. And why would he tell me, ‘Say hello to all the stars,’ when I’m stuck in here? Feeling a shiver of hope run through him, Julius made an effort to brush it away. No, I’m not letting you bother me and ruin this day.

He couldn’t ask Reese now, as he and the other night orderlies had finished their shifts and Orderly Evans had taken charge of the ward. Evans, hell. But he’s not that bad. There are worse. Julius watched him trying to get Tiny Bill out of bed. ‘Come on now, you were right as rain just yesterday.’ Tiny Bill, a giant boulder of a man, lay quite still, his eyes fixed on the ceiling. ‘This is the last time I’m asking you.’

‘See, Pictures?’ The patient who had a bed two along from Julius, Samson – another joke name, as he was a muscleless stick – threw a glance towards Tiny Bill and then gave Julius a confiding smile to say, aren’t we better off than him? ‘It’ll be treatment for Tiny Bill, I’ll bet.’

Julius flinched. Come on, Tiny Bill, try to get up. And then he was back to Orderly Reese’s odd remark. But there was something else, too. The look on his face. He had that smile people have when they know something you don’t. Julius shook his head. Stop thinking about it. But it was hard.

Orderly Evans gave Tiny Bill a scowl and turned away – it seemed Samson was right about the treatment – and then began handing out the morning’s post.

Sorry, Tiny Bill. ‘Unrhyw lythyrau i mi?’ Julius asked.

Orderly Evans gave a brief laugh. The orderlies were always amused to hear Julius, one of the few Englishmen in the Mid-Wales, trying to speak Welsh. ‘No, Pictures. No letters for you this morning.’

That’s more than a week now. Even Lou hasn’t written. Julius’ sister Louisa normally wrote as regularly as clockwork. I hope nothing’s wrong. I hope you haven’t been let down by that Italian fiancé of yours? He felt a sorrow in the offing. Everything’s fine, remember. You got nice clothes. This’ll be a good day. With rare obedience, the sorrow slipped away.

When everyone was dressed, Orderly Evans bellowed, ‘Breakfast,’ and, aside from Tiny Bill, who remained motionless in his bed, they began shuffling out of the ward, down the stairs and along a seemingly endless corridor. Patients of another ward were coming the other way and, seeing a wiry man among them, Julius edged towards the wall as far as he could from him, as did others, but the oncomer, talking rapidly to himself, went by without giving any of them so much as a glance.

Another strange thing was that Orderly Reese said it just before he finished his shift, so it was like he was saying goodbye. I suppose he could be leaving? But then he’d have told everyone? And they never leave, as there’s no other work in the town, or so everyone says. Julius shook his head. Go away. Leave me be.

When they reached the hall, with its smell of decades of brewed tea, Orderly Evans roared, ‘Grace,’ to sit them down at one of the long tables, and toast, butter, jam and tea were passed down.

Say what you like about this place, the food isn’t bad. All fresh from the farm. Julius was buttering his second piece of toast when, from the far end of the hall, there was a quick scraping of chairs and the sound of crockery smashing. Julius and the others at his table jumped to their feet to see. As I thought – one of the hard cases. A grey-haired, balding man, his eyes wide with fear, had got another by his neck and was shaking him back and forth. Three orderlies were already running over and soon had him pinned down on the ground. A wild shout rang out, ‘Bu’n dweud celwydd wrth y diafol amdanaf!’

‘Pictures,’ asked the Reverend, who’d been a clergyman in Hay, and knew no Welsh, ‘what’s he saying?’

‘He says the other one was telling lies about him to the Devil.’

The Reverend gave a little nod.

Be glad he was down there, far away from me.

‘Grace, grace!’ came a new roar, to sit them back down.

Samson jabbed his thumb in the direction of the hard case who’d been fighting. ‘It’ll be the monkey suit for him, I’ll bet.’ Once again, he was right and an orderly hurried into the hall with the garment, which he and the others set to work pulling onto the man’s arms.

And be glad it’s not me who’s getting the monkey suit this time. The room returned to something like calm. Orderly Reese is serious normally, true enough, but that doesn’t mean he mightn’t have been joking just today. He could have a funny side that I’ve never noticed. And for that matter he did tell me once that he likes Gracie Fields films. Yes, I bet that’s the only reason why he said it. Nothing more. Julius, as he accepted his new explanation, felt his spirits sag, yet also relief, that he was safe now from disappointment. But then, just when he had finally put the matter to rest, a further mystery came to taunt him. Breakfast over, there was a shout of ‘Boots’, to call him and the others who were fit for work to the shoe room, where Julius picked a laceless pair from the long line on the shelf. He clumped out into bright, mid-March sunshine and set out towards the farm.

Orderly Evans was walking beside him. ‘Morning, Pictures.’

‘Bore da.’ Another smile for my trying to speak Welsh.

‘First you’ll be on the pigs with the Reverend,’ said Orderly Evans. ‘And then you’ll be weeding the potatoes with Captain Williams. All right?’

‘All right.’ See? It’s turning out to be a good day, just like I said. You got good clothes. It’s sunny and bright. Look at the tiny green leaves on that tree, just beginning to sprout, and the shadows they make on the ground. I had to get a shot of a tree like that in that picture I did about Cornish smugglers, where the director wanted it to look like a gallows shaking in the wind. What was that picture called? He stopped himself. You’ll be feeding the pigs, which you enjoy, and the Reverend’s fine to work with. And though weeding potatoes is hard on the back, Captain Williams is a good sort. You always like spending time with him. It was then Julius noticed that Orderly Evans, whom he’d assumed would be hurrying on to tell the others their chores, was still beside him.

‘Oh, and another thing, Pictures. After lunch I’m to take you to Dr Morrison, as he wants a word.’

At the pigsty, Julius and the Reverend cleaned out the feed trays at the handpump, filled them with kitchen scraps and slid them into place. Usually, Julius liked to watch the pigs eat, snorting with content, but today he hardly saw them. Something was up, of that there was now no question. He was only called to Dr Morrison once a month and he’d last seen him less than a week ago. Why was he being summoned again? Though Julius could no longer crush his bubbling hopes, he tried at least to put them in doubt. It could be something quite different. Treatment, even. True, I’ve been much better lately, but that doesn’t mean I can be certain.

After feeding the pigs, Julius spent a couple of hours crouched in the potato field, tearing up weeds, while Captain Williams, who’d been buried alive when his trench collapsed, so everyone said, told him about the plan he was going to send to the top brass. ‘This one will take the Huns completely by surprise, Pictures. First we’ll launch an attack, all guns blazing, but then we’ll fall back like we’re in panic, and retreat past our trench and beyond. But when they come after us, we’ll have another whole line all ready, stronger than the old one. We’ll catch them in an ambush that’ll really tear them apart. But don’t tell a soul. D’you promise?’

‘I promise.’

Lunch was always the best meal of the day, and today was no exception – lamb, potatoes and carrots, with rhubarb and custard for pudding – but Julius hardly tasted a bite. He’d just finished his last spoonful when he saw Orderly Evans walking into the hall. What if I say the wrong thing? What if I ruin everything? His anxiousness grew as he walked into Dr Morrison’s office. The well-ordered tidiness – the framed medical qualifications and landscape pictures on the walls, the warm-brown carpet, the bookshelf with its neatly arranged books – was so unlike the rest of the hospital that it always made him feel out of place. Orderly Evans retreated discreetly into a corner and Dr Morrison ushered Julius to a seat.

‘How are you doing?’

‘Fine. I’m quite well, very well in fact, thank you. I’m really absolutely fine.’ Too much – I’m sure that was too much.

‘Everything all right on the ward? At the farm?’

‘All fine, thanks.’ He’s taking notes.

‘And what about the business that troubled you so much when you first came here? You told me there was a device somewhere in your belly. A kind of little wireless that was giving out signals.’

I knew you’d ask about that. ‘I was mistaken, Doctor. I don’t think about that any more.’ Hardly ever. Just sometimes.

‘But this device was there before?’

He’s trying to trick me. ‘No, I was quite wrong about it. It was never ever there.’ Of course it wasn’t. I’m almost sure. Or I got it out that time.

Dr Morrison jotted down a last note. ‘Well, I have some good news for you, Julius. Your stepfather telephoned yesterday and asked me if you’re ready to leave us and return to life outside this hospital. And I told him that, in my opinion, you are.’

For a moment, out of habit, Julius tried to resist the news but then he let go and a dizzying joy spread through him. It’s happening. It’s really happening. At last, after all this time. Just when I thought it never would. So I was right about Orderly Reese. He must’ve heard. What he said about Gracie Fields – that was his way of saying goodbye.

‘What d’you think?’

‘It’s wonderful news, Dr Morrison. Wonderful.’ A counter-wave passed through him as, for the first time, he pondered what this news might mean. I hope I’ll be all right. I hope it doesn’t all go bad and they send me back. He calmed himself. One thing at a time. All that matters now is that I’ll be out of here.

‘Your mother and stepfather will be coming up to collect you tomorrow at noon.’

Julius fought away a feeling of distaste. Don’t think meanly of them. They’re coming to take you away from here. Be grateful. Thank you, Mother. Thank you, Claude.

‘It’s all very sudden, I know,’ said Dr Morrison. ‘But I understand from your stepfather that there’s a family event coming up, which he and your mother would very much like you to attend. I don’t think they’ll mind my telling you. One of your sisters is getting married.’

‘Louisa?’

‘Yes, that’s right.’

So you’re getting hitched to your Roman, Lou. Good for you. I bet that’s the surprise you mentioned in your last letter. Quite a rush. Is it a shotgun wedding? As if it matters. And I’ll be there, I’ll be there. If they don’t change their minds.

But as the hours passed, there was no sign that anybody would. That night, Julius was so excited that as he lay on his bed, snores all around and sometimes a sudden shout, despite his dose of jungle juice he found it hard to sleep. In just a few hours I’ll be gone. I won’t be in this dormitory with snorers all around. And tomorrow I’ll be sleeping . . . He found it hard to think of where he might be. Somewhere else.

The next morning, he said his goodbyes to the orderlies and patients he was friendly with. Captain Williams gave him a salute. Does he think I’m going to the war? Samson seemed in awe of his leaving, and the Reverend, a little mournfully, offered his congratulations. Don’t smile too much. Show that you’re sorry that they’re still here.

After breakfast, Julius watched the others shuffle away to the shoe room without him and then Orderly Harris led him away to find a suit. ‘Usually with leavers we get the tailors to make something up,’ he explained apologetically, ‘but there was no time for you, Pictures, more’s the pity, as everything was such a rush.’ He waited patiently as Julius tried on a dozen jackets. ‘There’s lovely, eh?’ he said, when Julius found one that fitted relatively well. ‘So tell me, Pictures, how long have you been here with us now? A year?’

‘More like a year and a half.’

‘Well, aren’t you the lucky one, going away. Most that come in here never do, except when they lay their backs on the mortuary slab.’

Please God, though I don’t really believe in you, I beg you, don’t ever send me back to this place, nor to anywhere like it. Julius picked a pair of shoes, not the boots he wore when he worked at the farm, but real black shoes with laces, and though they were a little too big so his feet slid about, he smiled at the very sight of them. Proud in his new clothes, he waited in one of the day rooms, watching the patients who were too old or weak or too lost in the head to work on the farm, and who sat blank-faced as the radio played. And then, wonder of wonders, Orderly Harris returned and led him back down the interminable corridor, past the hall, below the clock tower, and into Dr Morrison’s office. The doctor, Julius’ mother Lilian and his stepfather Claude all turned together as he walked in. Thank you for coming for me. Mother looks strained. Claude looks annoyed. I’m sorry I never liked you, Claude, really I am. This will be a new start, I promise. Everything will be better between us from now. We’ll be great pals.

Julius’ mother stepped towards him but then stopped. ‘What’s that smell?’ Her voice sounded shrill.

‘Oh, that’ll be paraldehyde,’ said Dr Morrison.

Jungle juice. Julius felt a spasm of shame. I hardly notice it any more.

‘We use it to keep the patients calm,’ said Dr Morrison, turning to Julius. ‘Did they give you some last night?’ Seeing Julius’ nod, he frowned. ‘I specifically told them not to. But don’t you worry, Mrs Reid, as it’ll soon work its way through. Another day or two and the odour will be quite gone, I assure you.’

‘He smelt like that when we came last time, Pet,’ said Julius’ stepfather, reaching for her hand to squeeze it. ‘You were so upset you probably didn’t notice.’

Julius could smell it on himself now, ever more strongly, till he felt he reeked of the stuff.

‘A couple of things,’ said Dr Morrison, businesslike now. ‘It’s very important that Julius should avoid all alcohol – wine, spirits, beer, anything at all. I’m not saying that was the cause of his problems, but his drinking won’t have helped.’

Claude gave Julius an expectant look.

‘Of course,’ said Julius. ‘I promise I won’t touch a drop.’

‘Very good,’ said Dr Morrison with an approving smile. ‘And if you have more strange thoughts or feel troubled, I want you to tell someone right away. Someone you’re close to. One of your family.’

Which? Julius smothered the thought. They’re getting me out of here.

‘I will. I promise.’ Is that it?

It seemed so. Claude reached out to shake Dr Morrison’s hand. ‘I want to thank you, Teddy, for keeping such a good eye on him.’ Julius’ mother cooed agreement. Goodbyes were said.

It’s happening. I’m walking out of the waiting room.

‘Teddy Morrison’s a good man,’ said Claude. ‘A damn good man. Did I tell you we were at school together?’

You sound angry. Did I say something wrong? ‘Mother mentioned it in one of her letters,’ said Julius. The detail had stood out, as her correspondence rarely strayed from describing small, everyday occurrences: tea with neighbours, lunch with relatives, or a new watercolour she had finished, of a tree in blossom in the garden or a pretty scene on the river with an old sailing boat.

‘He was almost head boy. Should’ve been, too.’

Here’s the main door. And here I am, stepping out into the sunlight. It all seems so easy, so quick. When I woke yesterday morning I had no inkling this might happen, not the slightest idea. Already that seems half an age ago. And look, it’s the car! The same old car.

Claude waved to the driver, who was leaning against the door reading the paper and hadn’t seen. ‘Come on, man, for goodness’ sake,’ Claude murmured, waving again.

Mother looks so awkward. I should say something, but I can’t think what. ‘It’s been quite a while.’

It was the wrong thing. ‘We meant to come up a few weeks ago,’ said Lilian, flustered, ‘but we wanted to be sure you were ready, and then . . .’

Claude’s giving me a scowl. I wasn’t complaining, really I wasn’t. ‘I’m just so glad you came.’ Yes, that’s better.

Lilian gave a little smile, but then the startled look she’d had when she smelt the jungle juice returned. ‘What happened to your clothes?’

She thinks this suit’s awful. And I thought it was rather good. ‘They would’ve made something up for me but there wasn’t time,’ Julius explained. I’m talking too fast. Slow down. ‘So I had to pick it from what there was. Everyone’s clothes get mixed up here, you see.’

‘He was very oddly dressed when we came up before, remember, Pet?’ said Claude, again looking towards the car. ‘What does he think he’s doing?’ He shouted out, ‘Sam!’

Sam? Now that he looked more carefully at the driver, who was hurriedly folding away his paper, Julius realized he didn’t know him. ‘What happened to Toby?’

‘We couldn’t keep him on,’ said Claude. ‘You’ll find there have been quite a few changes since you . . .’ He left the phrase hanging. ‘Things got very sticky for the business when the government took the pound off the gold standard. We owed for the wine that we’d already been sent and then the franc went sky-high. I tell you, there were a couple of times when I thought I might go under. Cook had to go, too. Your poor mother’s been a perfect saint, making all our meals.’

Her investments must have taken quite a dive.

‘I’ve rather enjoyed it,’ said Lilian. ‘But it’s been awfully difficult for your poor father.’

My stepfather. You always say that. Julius stopped himself. Don’t get annoyed. They came to get you, remember. Think well of them.

‘That’s why we had to take you out of Ticehurst,’ said Claude. ‘When we realized that this was all going to take a good while . . .’

Ticehurst? Julius hadn’t even known the name. He had a hazy recollection of heavy wooden furniture, billiard tables and well-kept lawns. He’d had his own room. There had been a patient down the corridor who the orderlies fawned on and addressed as Your Grace.

‘And then I remembered that my old pal Teddy Morrison had gone into this . . . this . . .’ Again, Claude struggled for the right word, ‘. . . this line of work. So I did a bit of detective work and found he was up here. I gave him a bell and he said, but of course, Claude, send your boy Julius over right away as a private patient. I’ll look after him.’

You’re awkward because you sent me somewhere cheap. ‘Actually, I think I preferred it here,’ Julius said. ‘Even though I was on a ward and all the rest. The orderlies are friendlier. And I liked working on the farm.’ Yes – that was the right thing to say. They look relieved. Mother, anyway.

‘Ah, here’s Sam,’ said Claude.

The car stopped before them and the driver climbed out to open the doors. Julius took his seat in the front. As they began to move off, he watched through the wing mirror as the hospital and the clock tower shrank away and, to his surprise, he felt a sudden urge to call out for them to stop. Out here everything feels so wide and open. I feel safe in there, in a way. I know everything – which orderlies are kind and which ones aren’t, which boots to pick in the shoe room and how to do the farm chores. I know the patients, who to talk to and who to keep well clear of, and how to read faces for trouble. He closed his eyes for a moment and, as they reached the main road, he felt himself grow calmer. I’ll be all right. I’ll be fine.

‘It’s already almost half past twelve,’ said Claude. ‘Perhaps we should catch a bite to eat somewhere nearby before they stop serving. It’s a long drive home.’

‘There’s a place in the town that does lunch,’ said Julius. ‘It’s not bad.’

‘Really?’

He can’t understand how I know. Julius swivelled round in his seat to face them. ‘One of the orderlies would sometimes take a few of us there as a treat.’ Their faces. How stupid of me. Of course, they don’t want to go to a place where they might meet people from the hospital.

‘Or there might be a pretty little place along the road,’ said his mother, her voice rising again.

‘What a nice idea, Pet,’ said Claude hurriedly.

Already they had reached Talgarth. Sam the driver stopped at the crossroads. ‘I don’t suppose you remember which way we drove in, Major?’ asked Sam.

Don’t ask me. I was in the back of a van when I first arrived, trussed up like a chicken, and I couldn’t see a thing.

‘Let me see,’ said Claude. ‘I think it was from over there, wasn’t it?’

‘Right you are, Major. Yes, that looks like the one.’

They drove out into fields, and then passed down a narrow road with lines of trees to either side, their branches meeting overhead, so it seemed as if they were going through a kind of tunnel, flecked green with tiny spring leaves. Julius glanced up at the foliage speeding by above him – that would make a good shot – and felt his spirits rise. It’s so beautiful here. And just think, I can go anywhere I want. There’s nobody to tell me to sit down or come inside or put on my boots or take my jungle juice. I could go and take a walk on that hill, or sit on that gate for just as long as I like.

The car had fallen into silence. I should say something. He had no trouble thinking what. In one of her letters of the previous summer, amid accounts of teas and watercolour paintings, Lilian had mentioned that Julius’ half-sister Harriet had married a distant cousin, Harold White. To Julius’ surprise, his mother had offered no further details of this momentous news, and though he had asked about it several times in his replies, she had never elaborated. Julius found it hard to believe. Harriet married. I still think of her as a schoolgirl. He tried to remember when he had last seen her. The time when she came to the studios, probably. That must be almost two years ago. People can change a lot in two years.

Julius had been about to start work on Waltzing in Warsaw, his first chance to shoot a quality, full-budget picture rather than a quota quickie, and, anxious to make a success of it, he had been busy checking the sets and meeting the others who were to work on the film, yet he had found time to give Harriet a tour of the studio. When they passed a well-known screen star he expected her to be impressed, but she’d hardly given him a glance. Afterwards, over lunch in the canteen, she asked Julius a series of questions about how films were made and then had him recount the entire plot of Waltzing in Warsaw, which she disapproved of, complaining that he should have been involved in something more serious. As if I minded what it was. I was just glad to be working on a big film.

As to Harriet’s new husband, Harold White, Julius hadn’t seen him for ten years or more, and he remembered him as an excitable boy. He was always talking about what he’d be doing next, whether it was next year, in his life ahead, or whether he should ring for a pot of tea. And then something went wrong for him. Julius tried to remember. That was it. Harold had set up a clandestine school magazine in which he wrote caustic comments about the teachers, and when this was discovered, he was expelled. Harriet and Harold. Harold and Harriet. H and H. ‘And of course Harriet’s got married,’ Julius said. ‘How was that?’

‘Dreadful,’ said Claude. ‘Utterly irresponsible. And so ungrateful to your poor mother.’

How was I to know? That’s why Mother wouldn’t tell me anything about the wedding in her letters.

Harold and Harriet, Claude explained sourly, had eloped to Mexico together, leaving only a note. ‘They wanted to go to Russia, so I heard,’ said Claude, ‘but they couldn’t get a visa. I always thought Harold was a decent chap, but he’s turned into the most awful type. A fanatical Red. And he has poor Harriet completely under his spell.’

Julius thought of Harold’s subversive school magazine and Harriet’s disapproval of Waltzing in Warsaw. As if Harriet could be under anybody’s spell.

‘They wanted to stay on in Mexico,’ said Claude, ‘but then Harold got ill with a bad stomach, that sort of thing. Now they’re in some awful slum in Bermondsey.’

‘They’re very young,’ said Lilian indulgently. ‘I’m sure they’ll change their ways with time.’

‘Let’s hope so,’ said Claude. ‘But . . .’ He stopped because Sam had slowed the car.

‘Sorry to bother you, Major, but I’m not sure this road looks quite right.’

‘Not again,’ murmured Julius’ mother softly.

Julius felt himself smile. Claude was always terrible at directions, and now he’s found a driver who’s just as bad.

They were approaching a village. ‘What about asking her?’ said Claude, pointing to a woman who was emerging from her house, carrying a sack of potatoes.

Sam stopped the car beside her and had Julius wind down his window. ‘Excuse me, missus,’ he said, leaning past Julius, ‘but can you tell us the way back to England?’

Julius saw the confused look on her face. She doesn’t understand. ‘Rydum am fynd i Loegr?’ he asked.

‘Rhaid i mi nôl fy ngŵr,’ she answered, smiling now. She put down the sack and went back towards the house, calling out, ‘Daffydd?’

‘What the hell was that?’ demanded Claude.

I should have kept quiet. ‘I learned a bit of Welsh in the hospital,’ Julius explained apologetically. ‘Some of them hardly speak English there.’ And it helped, somehow. I don’t know why, but I felt better when I tried to speak another language. He nodded towards the house. ‘She’s gone to fetch her husband.’

A moment later the woman re-emerged from the house, now followed by a man who walked with a crutch, his left trouser leg sewn up, empty. ‘Yes?’ he asked.

‘We’re lost,’ said Sam. ‘We’re trying to get to Hereford.’

‘Well, you’re quite wrong up here. You want to go back the way you just came, and then when you get into Talgarth, turn right.’

As Sam thanked him, Claude wound down his window and held out a small silver coin. ‘Please take this as a token of our gratitude. I was in France too. We old servicemen have to stick together, eh?’

You were in the Supply Corps. You never saw a trench. Julius stopped himself. Don’t think meanly of him.

The other man looked at the sixpence for a moment and then slipped it into his pocket. ‘Well, ta.’

‘A good man,’ said Claude as Sam turned the car around. ‘A damn good man. I tell you, the ordinary working men of this country are as good as they come. Pure gold. Everything would be fine if it wasn’t for these agitators, leading them down the garden path. Take those unemployed marcher chaps we ran into yesterday when we got a little lost. Where was that?’

‘Wolverhampton, Major,’ said Sam. ‘I’m pretty sure it was Wolverhampton.’

‘They’d have been right as rain if agitators hadn’t got to them.’

‘That was so awful,’ said Julius’ mother. ‘They were all shouting and then one spat on the windscreen.’

Julius could imagine the scene: the ragged crowd around the car, angry faces looking in, then one leans close and . . .

‘Tom will sort it all out,’ said Claude briskly.

‘Tom?’ asked Julius.

‘Mosley, of course,’ said Claude. ‘Oswald Mosley. To his good friends he’s always Tom.’

For a moment Julius tried to make sense of the name. A politician. Julius had never been too interested in politics, while it was rarely discussed in the Mid-Wales Hospital. Religion, yes, that came up all the time. Like the hard case who’d started that trouble at breakfast. Was that really just yesterday? ‘Mosley’s in the Labour Party, isn’t he?’

Claude laughed. ‘That was yonks ago. He soon saw through that awful shower. He set up his own party, the New Party. You must’ve heard about it, as that was before you . . . Anyway, then he went the whole hog and now it’s the BUF, the British Union of Fascists. I’m in, so is your mother, and Sam here, too. That’s how we found you, isn’t it, Sam?’

Sam gave a smile of confirmation.

‘Of course, I’m just in the women’s section,’ said Lilian. ‘I should really go more often than I do.’

‘But you’re a paid-up member, Pet, and that’s what matters,’ said Claude approvingly. ‘I’m not full-time, what with running the business, but I do what I can. And I haven’t told you this yet, Pet, but I’ve half a mind to stand at the next election. What would you say to that, eh? Being the wife of an MP. Perhaps even a Cabinet Minister?’

Lilian smiled uneasily. ‘Lovely.’

I’ve been in that place so long that I don’t know anything any more. ‘Fascists?’ Julius said. ‘Like Mussolini?’

‘That’s the ticket,’ said Claude. ‘But British, of course. British through and through.’

I never much liked Mussolini. All that strutting about in his uniform and shouting. But then what do I know? Perhaps everyone’s in this BUF now? Perhaps I should be, too. Though Claude didn’t say I should join. They probably wouldn’t want me.

They had reached Talgarth, where Sam turned right at the junction as instructed, and before long they reached Hay-on-Wye. They passed a sign stating that they were entering England and moments later Claude pointed to a pub with a sign outside offering sandwiches. ‘What about that little place over there?’

‘Perfect,’ said Lilian.

Sam stayed in the car and Claude, promising to bring him lunch, led the rest of them into the saloon bar. How nice it is to see women’s faces. One, sitting at a table across the room, looked familiar. She reminds me of one of the actresses I did portraits of. Edna Berger, that was her name. Julius would take stills of actors when they had finished filming for the day, and were still in costume and made-up. If he could convince the art director to leave them switched on, he used the lights on the set. To try and get my career going and move me up to assistant cameraman. If I got some good shots then they might ask me to do their next film. Julius recalled his own ambition with a slight sense of wonder, as if it had belonged to somebody else. And it worked, too, with Edna.

Plates of musty-looking ham sandwiches had arrived. ‘So we’ll be setting out on Sunday,’ said Claude.

‘Setting out for where?’

‘Rome, of course.’

Julius had assumed that his sister was getting married in London and for a moment he found the news hard to take in. I’m going to Italy? Italy, where I’ve never been? So many things were happening so quickly that he had a sense of precariousness, as if it might all topple away in an instant. Yesterday I was pulling up weeds with Captain Williams, without much hope of ever doing anything else, and now I’m going to Italy. What’s Italy like? For a moment his mind went blank. Pasta and paintings, churches and ruins.

‘I told her, stand your ground, but no, she’s doing it all their way, more’s the pity,’ said Claude grumpily. ‘She has a priest who’s teaching her all that Catholic mumbo jumbo nonsense. But I suppose you can’t have everything, and she’s twenty-six now. I mean, thank goodness she’s finally found somebody.’

Is twenty-six so old?

‘And her chap seems a very good egg. Italian, of course, but a very decent sort. He’s something in the government over there.’

‘Their home office,’ said Lilian. ‘Or is it the foreign office?’

‘One of them. And he’s doing rather well, so I understand. He’s always dashing off to meet Mussolini. Frederico di something-or-other, he’s called. Quite a mouthful so we all just call him Freddy. We both liked him when they came over at Christmas, didn’t we, Pet?’

‘Loved him,’ said Julius’ mother.

Julius felt a faint jab of pain. You came all the way to England, Lou, and you didn’t even write and say, let alone come up and see me? For that matter, you never troubled to tell me that you were getting married.

‘And the wedding’s in a darling little church,’ said Lilian. ‘According to Louisa, it’s almost as old as Jesus himself.’

Claude began recounting the plans for the journey. ‘I have to say it all worked out rather well. There are some wineries that I’ve been meaning to visit for a while so I thought, why not motor down and make a trip of it? And it fits in perfectly with your little brother Frank’s Easter holidays.’

Little Frank. Julius tried not to let his spirits sag.

‘We’ll stay a couple of nights in Paris to see Aunt Edith and Uncle Walter.’

More faces Julius hadn’t seen for many years. ‘I thought they were in India?’

‘They moved to Paris a year or so ago, after Walter retired,’ said Claude. ‘And from there we’ll go across to Munich to pick up Maude.’

Claude and Maude. Maude and Claude. I can’t believe they never thought of that. So that’s where she is – Munich