20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

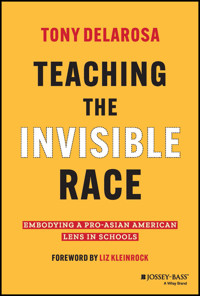

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

Transform How You Teach Asian American Narratives in your Schools! In Teaching the Invisible Race, anti-bias and anti-racist educator and researcher Tony DelaRosa (he, siya) delivers an insightful and hands-on treatment of how to embody a pro-Asian American lens in your classroom while combating anti-Asian hate in your school. The author offers stories, case studies, research, and frameworks that will help you build the knowledge, mindset, and skills you need to teach Asian-American history and stories in your curriculum. You'll learn to embrace Asian American joy and a pro-Asian American lens--as opposed to a deficit lens--that is inclusive of Brown and Southeast Asian American perspectives and disability narratives. You'll also find: * Self-interrogation exercises regarding major Asian American concepts and social movements * Ways to center Asian Americans in your classroom and your school * Information about how white supremacy and anti-Blackness manifest in relation to Asian America, both internally and externally An essential resource for educators, school administrators, and K-12 school leaders, Teaching the Invisible Race will also earn a place in the hands of parents, families, and community members with an interest in advancing social justice in the Asian American context.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 341

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Praise for

Teaching the Invisible Race

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

How Will They Hold Us?

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Introduction

The Term “Pro–Asian American”

Who Does This Book Center?

Who Is the Audience?

The Writing Process, Theories, Analysis, and Inquiry

How This Book Is Structured

The Cadence

Part 1: Teach Us Visible by Remembering Us

Chapter 1: What Do You Know About Asian America? Self‐Assessment and Framework

The Personal Is Political

The Self‐Assessment

The Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 2: Windows, Mirrors, and Sliding Glass Doors Framework

The Personal Is Political

The Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 3: Timeline of Anti–Asian American Racism and Violence

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 4: Timeline of Pro–Asian American Milestones and Permissions

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Part 2: Teach Us Visible by Centering Us

Chapter 5: Intersectionality, Plurality, and Asian Americans

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 6: Isang Bagsak as an Educational Framework

The Personal Is Political

The Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 7: Colonization, War, Colonial Mentality, and Settler Colonialism

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 8: Asian American Queer and Trans Perspectives

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 9: Immigration and Undocu–Asian American

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Notes

Chapter 10: Asian Americans, Disability Narratives, and Crip Ecology

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Part 3: Teach Us Visible by Celebrating Us

Chapter 11: Teaching Us Visible Through Art, Poetry, and Hip‐Hop

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 12: Teaching Asian American Studies Through Pop Culture

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Part 4: Teach Us Visible by Moving with Us

Chapter 13: Working with Asian American Students, Staff, and Families

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 14: Combating Anti‐Asian Hate Case Study Workshop

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Chapter 15: Asian America and Abolition

The Personal Is Political

Praxis: Action and Reflection

A Movement, Not a Moment

Epilogue

Glossary

References

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 6

Figure 6.1 Anna Julia Cooper (left) and Ida B. Wells (right)

Figure 6.2 “No History No Self” sign

Figure 6.3 Blasian March

Chapter 7

Figure 7.1 WASP pilot

Figure 7.2 Filipino World War II veteran

Figure 7.3 Colonization map

Figure 7.4 Decolonial Teaching Practices

Chapter 8

Figure 8.1 Tony DelaRosa dressed in his Filipino barong (Filipino traditiona...

Chapter 9

Figure 9.1 First day of school in the United States, January 1997

Chapter 11

Figure 11.1 Tony DelaRosa next to Saul Williams at Cedarville University

Figure 11.2 Station 3 Artwork: “Very Asian Feelings” by Amanda Phingbodhipak...

Figure 11.3 Station 4 Artwork: “Homework” a poem by Amanda Phingboddhipakkiy...

Figure 11.4 Station 5 Artwork: “Snack” a poem by Amanda Phingboddhipakkiya

Figure 11.5 Station 6 Artwork: “We are More” Protest Images by Amanda Phingb...

Chapter 13

Figure 13.1 Tony DelaRosa facilitating the panel “Are Asians People of Color...

1

Figure E.1 A tweet that says “Happiest #LunarNewYear2023 to my Asian diaspor...

Figure E.2 2022 Stop AAPI Hate Report Card

Guide

Cover Page

Praise for Teaching the Invisible Race

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

How Will They Hold Us?

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Epilogue

Glossary

References

Index

Wiley End User License Agreement

Pages

i

v

vi

vii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xix

xx

xxi

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvi

xxvii

xxviii

xxix

xxx

xxxi

xxxii

xxxiii

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

189

190

191

192

193

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

Praise for Teaching the Invisible Race

“DelaRosa's book, Teaching the Invisible Race, offers genuine ways for Asian Americans to be seen and heard. DelaRosa puts the teachings of our ancestors in conversation with current and future educators by weaving together spoken word, stories, historical evidence, and what I believe is most compelling—pauses in the text—where we ask ourselves questions about what we are learning and what it does to us. It is here, where we ALL become visible.

Dr. Allyson Tintiangco‐Cubales, professor of Ethnic Studies, San Francisco State University

“What do you remember being taught about Asian American History in your K‐12 education experience? What Asian American scholars and heroes can you name without looking them up? With Teaching the Invisible Race, Tony DelaRosa fills in a crucial gap in scholarship for educators and he does so in a book that is engaging, practical, and inspiring. Thank you, Tony, for bringing this important work to the field.”

Dr. Tina Owen‐Moore, superintendent at School District of Cudahy, Wisconsin

“Tony DelaRosa is the champion we all need. As a fellow parent and journalist, it is so exciting to see Tony taking these tremendous steps to make meaningful change in the lives of our children! We need to celebrate all of our contributions, including that of our very large, diverse, and complex Asian diaspora.”

Michelle Li, founder of Very Asian Foundation & Reporter

“Tony DelaRosa is a voice of a generation. His bravery and expertise makes him a voice we all must take note and learn from. In the face of censorship, Teaching the Invisible Race is an urgent read and resource for anyone who cares about the fate of future generations.”

Tonya Mosley, journalist, cohost of NPR's “Fresh Air”

Teaching the Invisible Race

Embodying a Pro‒Asian American Lens in Schools

Tony DelaRosa

Copyright © 2024 Jossey‐Bass Publishing. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

Except as expressly noted below, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 750‐4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Certain pages from this book (except those for which reprint permission must be obtained from the primary sources) are designed for educational/training purposes and may be reproduced. These pages are designated by the appearance of copyright notices at the foot of the page. This free permission is restricted to limited customization of these materials for your organization and the paper reproduction of the materials for educational/training events. It does not allow for systematic or large‐scale reproduction, distribution (more than 100 copies per page, per year), transmission, electronic reproduction or inclusion in any publications offered for sale or used for commercial purposes—none of which may be done without prior written permission of the Publisher.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Control Number:

Hardback: 9781119930235

ePDF: 9781119930259

epub: 9781119930242

Cover Design: Wiley

To…

My son, Sebastian Rizal DelaRosa.

My Pampangan & Caviteńo Ancestors: Apung Dena, Grandma Clarita, and Grandpa Tony.

My Filipinx/a/o American Artists, Educators, Community‐Engaged Scholars, and Activists.

The Asian American Avengers of past and present, both in and out of this book.

Foreword

During one of my early years as a classroom teacher, I was patting myself on the back for completing a unit on the social construction of race with my third grade class. I asked my students to journal about their experience throughout the lessons and to write down their reflections and any lingering questions. As I flipped through their responses and congratulated myself, I came across a question from a student that knocked me off my pedestal: “Why haven't we talked about my race?”

What floored me was that this honest question was written by one of my Asian students. How could I, an Asian American, a self‐proclaimed social justice educator, have made such an egregious mistake?

I spent the following hours, days, and weeks racking my memory of my own experiences as a K–12 student. When did my teachers bring up Asian American history? When had I ever been invited to explore my identity as an adopted, Jewish, Korean American girl?

The unfortunate truth was, there wasn't much to reflect upon. In elementary school, Asian celebrations were often lumped into lessons such as “holidays around the world.” There was minimal representation in our picture books, like The Korean Cinderella and Tikki Tikki Tembo, both written by white authors and spoiler—the books haven't aged well. In middle school, we read The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck (also a white woman). When high school rolled around, we barely touched on Chinese laborers who built the railroads, and anything we learned about the Vietnam War was presented from the American perspective.

Looking back, I realize I was perpetuating the same erasure I had experienced as a student. Since I had no model or exemplar of what culturally responsive, anti‐bias Asian American education could look like, I had difficulty bringing it to life in my own practice. There was a staggering amount of learning and unlearning I needed to do.

Tony and I formed our friendship through social media, sharing ideas, and supporting each other's work. The first time we met in person was at a Teach for America's Asian American and Pacific Islander gathering in 2020, about three weeks before the world shut down. We ate dim sum, drank boba, and called ourselves “The Asian Avengers.” None of us knew how lucky we would be to come together at this time, how we would lean on one another in the months and years to come, and how our professional relationships and friendships would only grow stronger with time.

Tony's debut, Teaching the Invisible Race, could not have come at a better time as it is relevant in a multitude of spaces. It is truly the book that I not only wish I had read when I began my path as an educator, but also the book I wish had been available for my own teachers to learn from. I'm grateful to call Tony a friend, peer, and teacher.

Teaching the Invisible Race is unlike any book you're likely to come across on the subject of Asian American education. Tony blends his unique skills as a classroom teacher, mentor, poet, researcher, and activist to connect the personal with the intellectual. He shares his stunning lyrical voice with his audience, while also providing historical context, academic frameworks, and practical examples of how this work can come to life in the classroom.

I am so grateful to you, Dear Reader, for picking up this book so we can come together and not only represent but also affirm the histories and identities of the Asian American community.

In solidarity,

Liz Kleinrock

founder, Teach and Transform

author, Start Here Start Now: A Guide to Anti‐bias and Anti‐racist Work in Your School Community

How Will They Hold Us?

On May 31, 2021, HB 376, also known as the TEAACH Act, passed in Illinois, mandating that Asian American history be taught across the state. The TEAACH Act spurred other states to follow suit. The following poem was also published previously in the Asian American Policy Review at the Harvard Kennedy School and featured in the Hulu special “Heritage Heroes.”

What separates a mandate from a movement

are the shepherds who inherit the stories.

And what will teachers do with us?

“Fastest growing racial group”

48 countries deep

2300+ languages

and an ocean of dialects

Who will carry our stories?

Will they cradle us precious

like Yuri did Malcolm

at his darkest of hours?

Like the Black Panthers did Yellow and Brown Power

Like at the International Hotel, Philippine American War,

Or like Blasian March building Black, Asian, and Blasian radical rapport?

How loud will they teach this “invisible race”

Beyond the silence outside of October and May?

What if they drop one of us?

Will they pick us up like a fallen soldier

or will they stumble over a minefield

and fumble us forgotten?

Who entrusted them

with our spices, jackfruit, and diamonds?

Will they style us windows and pick up a mirror?

Will they dance a revolution or will they wallflower reform?

Will they wade in the binary or swim ultraviolet and upstream?

Will they study our mountains and movements?

Do they know us beyond a hashtag?

Beyond San Francisco and Time Square?

beyond the Black & white binary that flattens and binds us?

Can they name our mothers before our fathers?

Can they even name our fathers?

Will they name themselves now: “allies”

After they discover our names in a book club

that doesn't scent of our vinegar, sweat, blood, and dust?

When the time comes, will they play our battle drums?

Or will they steal or plant our Chrysanthemums?

About the Author

Tony DelaRosa (he/siya) is an award winning Filipino American anti‐bias and anti‐racist educator, leadership coach, motivational speaker, spoken word poet, racial equity strategist, and researcher. He holds a BA in Asian Studies at the University of Cincinnati, a M.Ed with a focus on Arts Education and Non‐Profit Management at Harvard University, and is currently pursuing his PhD in Education Leadership and Policy Analysis at the University of Wisconsin Madison as an Education Graduate Research Scholar. In 2021, he received the INSPIRE Award given by the National Association of Asian American Professionals and United Airlines. In 2023, he received the Community Trailblazer Award from The Asian American Foundation (TAAF), where his work is featured on TAAF's Heritage Heroes documentary streaming on Hulu.

His work has also been featured in NPR, Harvard Ed Magazine, the Smithsonian, Columbia University's Hechinger Report, Hyphen Magazine: Asian American Unabridged, and elsewhere. He has co‐founded NYC's first Asian American teacher support, development, and retention initiative called AATEND under NYC Men Teach, the NYC DOE, and Office of the Mayor. He served as a director of Leadership Development at Teach for America coaching teachers and leading DEI strategy. Today, he coaches CEOs and principals on crafting and refining their short‐term and long‐term DEI strategy.

In his free time he enjoys spending time with his wife and son and checking out the latest hit RPG or anime series.

Follow him on IG and Twitter at @TonyRosaSpeaks.

Acknowledgments

I wrote this book on Tequesta (Miami, FL) and HoChunk (Madison, WI) land. It's important to first acknowledge them as original inheritors and nurturers of these regions to remind ourselves that we are guests and settlers on someone else's land. The land acknowledgment is a way of grounding you in decolonial thought as you approach this book.

This is a perfect segue into my second acknowledgment, which is to highlight my Filipino ancestors. While the Filipinos were the first Asian settlers in the United States in 1587, we don't learn about them in school. So allow me to shout out a few Filipino revolutionaries: Larry Itliong, Al Robles, Philip Vera Cruz, Gabriela Silong, Carlos Bulosan, Dr. Jose Rizal, and Dr. Dawn Mabalon. Being unapologetically Filipino and Filipino American and taking up space gave me the confidence, wisdom, and makibaka (“fight” in Tagalog) to speak truth to power through poetry, education, and critical analysis. Because of you all, I'm helping shape the education sector and co‐define, amongst other Filipino American critical scholars, what it means to have a Filipino American critical ethnic lens on the world.

Third, I have to thank my “Asian American Avengers” both in and out of this book. I first heard of this term when I was consulting with the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center with a group of Asian American educators, scholars, and activists. I'm applying this term to any Asian American activist in their respective fields. The first few people I will thank are: Cap Aguilar, Sarah Ha, and Soukprida Phetmisy. These three Asian American women lifted me up during my education practitioner years. Cap and I worked together in Boston where she amplified my story and cultivated healing, reflective, and celebratory spaces for Asian American teachers on top of doing her job as a coach to 40 teachers during that time. Sarah Ha invited me to share my spoken word poem at a large affinity space at the Teach for America 25th Anniversary Summit and guided me as I led my first Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) teacher leadership summit in Oakland, CA. Soukprida Phetmisy and I co‐led the AANHPI teacher leadership summit. Since then, Soukprida and I have supported each other's endeavors through art, activism, and storytelling. We hold each other close.

Fourth, I'm amplifying my mentors at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) who I met in 2018, and stay connected to through my work. I have to start off with Dr. Tracie Jones who was the former director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at HGSE and now an assistant dean at MIT. She took me in and believed that an Asian American could and should lead Harvard's largest education conference for people of color called the “Alumni of Color Conference,” or AOCC. She trained me to be a cross‐racial coalition advocate, an entrepreneur, and community builder.

This book would also not be true without the mentorship of Dr. Christina Villarreal (Dr. V), my ethnic studies professor. Ethnic studies changed my life. You'll hear that from many students of ethnic studies because ethnic studies is a way of life. Dr. V's superpower is designing and leading critical discussions, while holding everyone in her spaces with love and compassion. Her classroom is the definition of abolitionist teaching because it bridges the class with community and inspires radical thought and stretches our imaginations. This leads me to Dr. Josephine Kim (Dr. Jo). She was my advisor when I co‐led the Pan‐Asian Coalition for Education (PACE). She guided me in centering Asian American studies and narratives at HGSE. Later, I got to serve as a teaching fellow for the inaugural Asian American studies course that she designed: H503M Race, Ethnicity, and Culture: Contemporary Issues in Asian America. In teaching and leading in H503M, I realized that one of my life's purposes is to amplify Asian American education through a critical ethnoracial lens everywhere I go. This class pushed me to pursue my doctorate.

Beyond the communities I've been directly involved in, I have to thank everyone who continues to support my own development as a community‐engaged scholar in ethnic studies: Ron Rapatalo, Richard Haynes, Jermona Intia, Amnat Chittaphong, Andrea Kim, The Board, Patrick Armstrong, Richard Leong, Dr. Kiona, Kim Saira, Dr. Christopher Emdin, Dr. Yolanda Sealey‐Ruiz, Dr. Judy Yu, Dr. Travis Bristol, Jerry Won, Liz Kleinrock, NAAAP, Francesca Hong, Kabby Hong, Michelle Li, the EdGRS Fellowship at UW‐Madison, Dr. Anjalé Welton, Dr. Erica Turner, Dr. Lesley Bartlett, Dr. Kevin Lawrence Henry, Dr. Karen Buenavista Hanna, Dr. Liza Talusan, Dr. E. J. David Ramos, and of course the beloved Dr. Kevin Nadal. Shout out to my fellow authors, Liz Kleinrock, Bianca Mabute‐Louie, and Kwame Sarfo‐Mensah, for holding space for me to exchange ideas about the book (excited to be in the lab with you).

Big thanks to my acquisitions editor, Amy Fandrei, who saw me talk with Elena Aguilar on an Instagram Live Chat about coaching practices, and believed I had a story to tell. Thank you Jossey‐Bass team for investing in me and the Asian American community through the development of this book.

Salamat to Ruby and Willy Delarosa (aka Mom and Dad). Your support since day one cannot be measured. From cradle to critical consciousness, you have pushed me to learn so much about who I am today and how I see the world.

Salamat to Ateh Roo (Rubilly DelaRosa aka my sis). You cheered me on from the start. You introduced me to poetry, and that opened up a portal to radical imagination. Thank you for the wonderful doodles you drew of the Asian American Avengers; your art is your activism.

Lastly, thank you to my wife and son. My son, Sebastian Rizal DelaRosa, lit a fire in me around why this work matters personally. I always had a passion for social justice, but now it feels so much more proximate that you are in our lives and heading to school. My wife and best friend, Stephanie Jimenez, showered me with love and support through reading, editing, and pushing my ideas to the fore. I would not be the feminist I am today without you.

Introduction

Dear Reader, thank you for holding this book. The way we hold each other is what grounds me in critical hope in times of crisis and in times of joy. It's 2023, and the Asian American community is facing a rising crisis of hate, racism, and violence stemming from systems of colonialism, exploitation, racial capitalism, xenophobia, sinophobia, white supremacy, and anti‐blackness.

Asian Americans know that this has been happening to us long before the pandemic. In the United States, anti‐Asian sentiment stems from racist and exclusionist policies like the 1790 Naturalization Act that restricted naturalization to only people identifying as “white.” Anti‐Asian sentiment stems from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which for decades banned Chinese people from entering the United States. This act was extended to people from the Philippines, India, and Japan (indeed, an entire “barred Asiatic zone” was established in 1917), lumping different national‐origin groups into a single racial category, the “Asiatic” (Ngai, 2021). Anti‐Asian sentiment is an American tradition set forth by some of our nation's leaders:

President Franklin D. Roosevelt with Executive Order 9066 (the internment of Japanese Americans)

President Lyndon B. Johnson's Hart‐Cellar Act of 1965 (shifting an immigrant quota system to a merit‐based system)

President Donald J. Trump's Executive Order 13769 in 2017 (also known as the “Muslim Ban”)

Today the number of anti‐Asian hate and violence incidents is reportedly soaring above 11,000, according to the organization Stop AAPI Hate 2022 report, which collected data between March 19, 2020, and March 31, 2022. These statistics don't even consider unreported incidents. Holding this book means you see us, hear us, and empathize with us.

The poem you read on the previous pages emerged from witnessing a wave of Asian American education policy slowly taking root across the United States. Of course I have to pay homage to the 1960's ethnic studies movement that manifested because of the Third World Liberation Front. While ethnic studies is mostly a bicoastal movement, specific Asian American students K–12 mandates began occurring recently, starting in Illinois with the Teach Equitable Asian American Community History Act (TEAACH Act). After the Act passed, many coalitions followed suit in different states, such as the Make Us Visible Connecticut and Make Us Visible New Jersey.

I chose the title Teaching the Invisible Race, because despite the anti–Asian American policies and incidents that I have outlined at large, people still render us invisible through gaslighting our oppression, excluding us from social justice education and conversations, through intentional omission, and homogenizing our vast and diverse experiences.

While my poem at the beginning of the book critiques how teachers as “shepherds” will hold us (teach our stories), this book aims at helping educators understand how to strengthen their own Asian American ethno‐racial literacy in order to teach it to their students. The outcome is culturally responsive and sustaining, paying homage to Dr. Gloria Ladson‐Billings's evolved work in Culturally Responsive‐Sustaining Pedagogy. Teaching the Invisible Race is Halo Halo, “mix‐mix” in Tagalog. When I say Halo Halo, I mean this book is a remix of story, poetry, concepts, theory, framework, case studies, interviews, and more. Beyond the fight of combating anti‐Asian sentiment, violence, and racism within ourselves and within the communities we serve, I'm pushing educators to hold both our fight and our joy together. To hold us close means you hold us beyond this moment and through this next stage of an evergreen movement.

The Term “Pro–Asian American”

CUNY professor Kevin Nadal explains how the terms “Yellow Power” and “Brown Power” stem from the Black Power Movement in the 1960s‐70s. In a similar light, I'm using the contemporary term “pro–Asian American” as an inspiration from the Black community who founded the term “pro‐Black” as a response to Black dehumanization and celebration for Black identity, history, culture, power, and futures.

In searching for the origins of the concept of “pro‐Black,” scholar mentors and friends pointed me to Marcus Garvey, a Black nationalist and pan‐Africanist, who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in the 1920s, which stressed Black pride, racial unity of African Americans, and a need to redeem Africa from white rule (Hill, 1983). Others have pointed me to the “Black is Beautiful” movement founded by Kwame Brathwaite and Elombe Brath in the 1960s‐70s, which broadly focused on embracing Black culture and identity, with a sub‐focus on emotional and psychological well‐being (National Museum of African American History & Culture). In a similar light, this book aims at exploring and educating on what it means to be pro–Asian American.

Asian American people have acted pro–Asian American without even labeling their actions as such through the building of Asian American employee resource groups, affinity spaces, businesses, movies, networks, and more. In a similar ethos to pro‐Blackness, “pro–Asian American” balances the concept of combating or fighting anti‐Asian hate and racism, since it is a symptom of white supremacy. “Pro–Asian American” means you are actively supporting the Asian American community with a big focus on low‐income Asian American communities that go invisible due to the model minority myth (i.e., Hmong, Lao, Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Thai, Cambodian, and more). “Pro–Asian American” means you are actively supporting Asian Americans with the notion that our liberation is tied to combating anti‐Blackness and embodying a pro‐Black lens. We owe our freedom to radical Black activists and organizers, many of whom are queer, trans, and non‐binary, who paved the path for us to thrive as a community. I speak more about the history of Black‐and‐Asian American relations later in the book when talking about Isang Bagsak pedagogy and cross‐racial solidarity.

Who Does This Book Center?

This book centers the narratives of Asian Americans: East, South, and Southeast. For clarity, East Asian refers to: mainland China, South Korea, North Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau. South Asia refers to Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka with Afghanistan also often included. Southeast Asia refers to the Philippines, Indonesia, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, Brunei, East Timor (or Timor‐Leste), Myanmar, Singapore, and Thailand. This book does not center West Asian Americans, Central Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders because they deserve their own books, and this book will not do these communities justice as it pertains to education. This is not to say that I won't mention narratives or histories from these areas, because I know there are many overlaps around cross‐racial coalitions in the fight for labor rights, in the fight against colonization, and in the fight for visibility in education. There is also overlap when we think about Asian Pacific Islander American Heritage Month (APIHM) in May.

Who Is the Audience?

Teaching the Invisible Race is geared toward upper elementary through high school English language arts, reading, social studies, and US history practitioners including teachers, instructional coaches, curriculum specialists, and anyone who has a stake in the realm of teaching and learning. This includes school administrators and counselors. This is the area of expertise that I taught and coached while working directly in schools. The examples and reproducibles in this book will reflect these content areas and grade levels. This book is also for those who identify as white, as well as who identify as People of Color (POC).

The Writing Process, Theories, Analysis, and Inquiry

While this is very much a practitioner's book, there are a few qualitative research logics that influenced my writing process, from the book design to the intake of interviews and readings and to the analysis of the content. These logics come from autoethnography, portraiture, narrative inquiry, community‐engaged scholarship, and Asian Crit.

Autoethnography allowed me to share my own story as a Filipino American spoken word artist. Spoken word poetry is a dialectic, and like the best forms of pedagogy, dialogue with self, student, and community is paramount. With the reflection questions placed throughout the book, they ask you to stop and reflect. This methodology influenced the beginning cadence of every chapter with the section entitled “The Personal Is Political.” I also wanted to emphasize the messiness that is being a Filipino American poet who has lived in San Diego, California, Cincinnati, Ohio, Indianapolis, Indiana, Boston, Massachusetts, Miami, Florida and now Madison, Wisconsin. Each place and time period influences how I think and write about being Asian American in the United States, which makes for a narrative hyper‐conscious of context.

Portraiture is the methodology that I learned from my former advisor at Harvard Graduate School of Education, Dr. Sara Lawrence‐Lightfoot. Dr. Lawrence‐Lightfoot pioneered this qualitative inquiry method in 1983 helping researchers understand the social, cultural, and political aspects of a place over time. Portraiture bridges art and science, examining the empirical with the aesthetic. You can see portraiture through myself having built a deep connection to the Asian American community to understand the social, cultural, and political aspects of our community both before, during, and after the #StopAsianHate movement. Being empirical about disaggregating the Asian American experience through a lens of intersectionality is necessary because it is living proof that we are more than a monolith.

The stereotype of Asian Americans is monochromatic, flattened and uninspiring, and I know that our community is the exact opposite. We are ultralight beams, buried in the past, and bursting into the future. Another aspect of portraiture is explicitly focusing on the “goodness” of the portrait and narrative around Asian Americans. When I refer to “goodness,” this is not to be confused with “success” and the trap of the model minority myth, but rather helping us unpack what it means to be “pro–Asian American.” Goodness, in the interpretive frame, means that the interviews are beautifully and compellingly written to celebrate self. How often do we get to see Asian American narratives celebrate themselves outside of the bento‐boxed stereotypes that the United States media has restricted us in? Also, “goodness” refers to this concept of being able to transport the “goods” or “qualities” of Asian America to the reader.

I chose narrative inquiry and a community‐engaged scholarship as approaches because it was the best mode to connect the dots between my autoethnography and the ethnography of Asian American artivists and education practitioners already embodying a pro–Asian American lens in their work. Similar to what Dr. Gloria Ladson‐Billings in The Dream Keepers states about objectivity, while I accept the empirical information about Asian Americans, I want to underscore “the primacy of objectivity” to help all of us lean into the messiness that is the Asian American experience. Community‐engaged scholarship, in particular, rooted my work with a power‐with framework across the Asian American interviewees that hold differing intersectionalities than my own, which dovetails into Asian Crit.

Asian Crit (or Asian Critical Race Theory) grew out of critical race scholarship, which focused more on a Black and white binary of analyzing how race and racism are endemic to the United States. Scholars such as Mari Matsuda and Robert S. Chang are early pioneers of this work. From the early work in 2013 of Dr. Samuel D. Museus and Dr. Jon S. Iftikar, they break down the AsianCrit framework into seven tenets:

Asianization,

the notion that racism is pervasive in society and racializes Asian Americans in distinct ways.

Transnational contexts,

the importance of recognizing that the lives of Asian Americans are shaped by historical/contemporary national and transnational contexts.

(Re)Constructive History

, the necessity to (re)construct history to include the voices and experiences of Asian Americans.

Strategic (Anti)essentialism,

the idea that dominant forces impact the racialization of Asian Americans in society and the ways that they reify and/or disrupt this racialization of themselves and other People of Color.

Intersectionality,

the notion that racism and other systems of oppression intersect in multiple ways and in multiple spaces.

Story, theory, and praxis

, that counterstories constructed by Asian Americans, theory, and practice must inform one another and should all be used for transformative purposes.

Commitment to social justice,

that the utilization of AsianCrit is a means to ending all forms of oppression. All of these tenets are core theories that influence how I talk about my story, the story of Asian America, and the charge for practitioners to teach us with nuance and care.

While I don't explicitly name all of the tenets of Asian Crit throughout the book, you will see connections to these concepts throughout.

How This Book Is Structured

This book has four main parts that divide the chapters.

Part 1

: “Teach Us Visible by Seeing and Remembering Us”

Part 2

: “Teach Us Visible by Centering Us”

Part 3

: “Teach Us Visible by Celebrating Us”

Part 4

: “Teach Us Visible by Moving with Us”

Part 1, “Teach Us Visible by Seeing and Remembering Us,” contains Chapters 1–4. Chapter 1, “What do you know about Asian America?” begins with a self‐assessment on how much you know about Asian American history, narratives, and studies as a whole. This was inspired by Liz Kleinrock's assessment for her students regarding Asian American narratives. The assessment does not aim to give you a rating, but more closely to force you to consider how much or little you know about Asian American topics.

Chapter 2, “Windows, Mirrors, and Sliding Glass Doors Framework,” focuses on Emily Styles and Rudine Sims Bishop's work. Outside of reflecting on “the amount of knowledge,” this method will enable you to connect to the book from your ethnoracial positionality. If you are an Asian American, then this book might serve as a mirror, as well as a window to other Asian American narratives. I acknowledge that Asian America is highly complex and we are not monolithic, however some of our stories do overlap across the diaspora, such as our relationship to exclusion, the model minority myth, and our relationships within the binary of white supremacy and anti‐Blackness. For non–Asian American people of color, this book might serve as both a mirror and window at times. As a white person, this book will serve as a window as you look into our histories, narratives, and pedagogies. At the end of Chapter 2, I charge you to create Sliding Glass Doors through the teaching of Asian American history and narratives.

Chapters 3 and 4 offer a timeline of laws, policies, and events that have had both a negative and positive impact in shaping the political landscape of Asian America today. Chapter 3, “Timeline of Anti–Asian American Racism and Violence,” should act as a reference because Asian Americans are often gaslighted with comments or treatment that dismisses their relationship to racism in the United States. In Chapter 4, “Timeline of Pro–Asian American Milestones and Permissions,” I offer a timeline of laws, policies, and events that symbolize Asian American milestones that have shaped the political power and landscape of Asian Americans. Understanding both positive and negative laws, policies, and events in history helps foster the knowledge base required to be pro–Asian American. After Part 1 of the book, which sets the tone and grounds us on how to navigate the book, the rest of the parts are less linear. Based on the self‐assessment, I encourage you to visit portions of the book that help you fill in gaps in knowledge or strengthens concepts that need extra love.

Part 2 of this book entitled, “Teach Us Visible by Centering Us.” The ethos behind centering us underscores the concepts of Asian American identity, intersectionality, and how we exist beyond the Black and white binary. This part of the book includes Chapters 5–10. Chapter 5