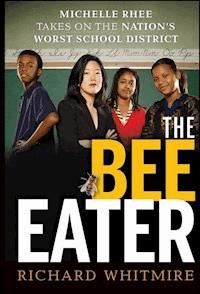

16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

The inside story of a maverick reformer with a take-no-prisoners management style Hailed by Oprah as a "warrior woman for our times," reviled by teachers unions as the enemy, Michelle Rhee, outgoing chancellor of Washington DC public schools, has become the controversial face of school reform. She has appeared on the cover of Time Magazine, and is currently featured as a hero in the documentary "Waiting for Superman." This is the story of her journey from good-girl daughter of Korean immigrants to tough-minded political game-changer. When Rhee first arrived in Washington, she found a school district that had been so broken for so long, that everyone had long since given up. The book provides an inside view of the union battles, the school closings, and contentious community politics that have been the subject of intense public interest and debate ? along with a rare look at Rhee's upbringing and life before DC. * Rhee has been featured in the documentary "Waiting for Superman" * Rhee's story points to a fresh way of addressing school improvement * Addresses fundamental problems in our current education system, and the politics of leadership The book includes an insert with photos from Rhee's personal and professional life, and an "exit" interview that sheds light on what she's learned and where the future might take her.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 379

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title page

Copyright page

Dedication

Preface

The Job Ahead

The Race Factor

Writing about Rhee

Full Disclosure

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Chapter One: An (Asian) American Life

Michelle’s Roots

The Wider World

Chapter Two: The Transformation Begins

“Hey, (Insert Last Name) Shut Up!”

Sucking It Up

Harlem Park: Years Two and Three

The Moment of Transformation

Chapter Three: Going National

Taking on a New (Teacher) Project

One-Two Punch

Chapter Four: Welcome to the Nation’s Education Superfund Site

Thirty-One Flavors of Failure

The New Broom

The Rhee Team

Chapter Five: Closing Schools

Prepping for Surgery

Best Laid Plans…

Fait Accompli

Chapter Six: Randi and Michelle

In Their Words

The Red and the Green

The Storyline Shifts

The National Scene

Time to Vote

Chapter Seven: New Hires, New Fires

Welcome to Anacostia

Jordon, Meet Sousa. Sousa, Principal Jordan

New Blood

Life Beyond Sousa

The Flip Side: Johnson Middle School

Chapter Eight: Up from the Foundations: The Challenge of High School Reform

Taking on Dunbar

The Bedford Takeover

2010–2011: The Success Unravels

Chapter Nine: Rhee’s Critics Find a Winning Storyline

The Hardy Backlash

Alienating the Council

Trial by Post

More Firings—and Return Fire

Chapter Ten: The Mayor’s Race

Exit Polling

Fenty’s Shortcomings

Chapter Eleven: Lessons Learned

What Rhee Did Right

Popular Mythology

Rhee’s True Missteps

Chapter Twelve: What’s Next?

The D.C. Legacy

Had There Been Four more Years

The National Legacy: Grasping for “Michelle Lite”

Looking Ahead

Notes

About the Author

Index

Supplemental Images

Wiley End User License Agreement

Copyright © 2011 by Richard Whitmire. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-BassA Wiley Imprint One Montgomery Street, Suite 1200, San Francisco, CA 94104-4594—www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Jossey-Bass also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-0-470-90529-69781118058039 ePDF9781118058046 eMobi9781118058053 ePub

For pretending that single-subject conversations for months in a row are perfectly normal, I thank my lovely wife, Robin.

PREFACE

A grownup might have missed the sign posted at Slowe Elementary in northeast Washington, D.C., but that’s beside the point. The sign wasn’t put there to catch the attention of adults. It was posted low on the wall, precisely at eye level for the elementary school children moving through the hallways. For those children, the sign was a daily reminder:

There is nothing a teacher can do to overcome what a parent and a student will not do.

For those children, the sign was a daily admonition that the teachers at Slowe were not responsible for students’ failings. We’re not the reason the test scores at this school are awful. We’re not why D.C. schools rank at the bottom of all the nation’s schools. Look to yourself, look to your parents. You are to blame.

Michelle Rhee visited Slowe immediately after she was appointed chancellor. It was a day marked by a flurry of school visits, in some cases unannounced. At Slowe, the principal herself unlocked the front door after Rhee and her entourage rang the bell. Her puzzled face gave it away: she had no idea who Rhee was. After introductions, a tour followed, but the visit only got more awkward as the group passed empty classroom after empty classroom. Slowe had been built for hundreds but bizarrely had been allowed to stay open with a mere eighty-three students, a testament to the powerlessness and, in some instances, fecklessness of the parade of superintendents who preceded Rhee (she was the tenth since 1988).

Most of the previous school chiefs had never even considered trying to close schools in the face of a school board and city council inclined to favor an array of special interest groups determined to block any changes to the status quo. Thus, schools such as Slowe were allowed to slog along, year after year, burning up millions of dollars in unneeded maintenance and other inefficiencies. And though it sounds outrageous, that wasn’t the saddest part of the story. Conventional wisdom might suggest that with only eighty-three students Slowe Elementary had a shot at being successful. Not so. Similar to the children at D.C.’s many other underused schools, children at Slowe lagged far behind their peers in other cities. At the time Rhee visited Slowe, 35 percent of the students scored at the proficient level in reading and only 15 percent in math.

“The test scores at Slowe were horrible,” recalls Tim Daly, Rhee’s colleague at The New Teacher Project (a teacher-recruiting organization Rhee helped found), who accompanied Rhee on the tour.1 It was Daly who noticed the sign in the hallway. Hesitant to trigger a scene during Rhee’s first day as chancellor, he didn’t tell her until she left the building. “I was thinking, this is the system she has become chancellor of: a system where it would be possible to get appointed chancellor and the principal seemed not to know it, possible for a school built for six hundred students to have fewer than ninety students in it, possible for a school to be failing for years and not get closed, and possible for a teacher to post a sign like that and no one tell the teacher to take it down.”

As Rhee would soon discover, that last point—why no one had demanded the sign be removed—was not the least bit mysterious. It wasn’t just one teacher, or one principal, who believed schools had minimal impact on children and therefore were held harmless if students failed to learn. Hundreds of teachers and administrators appeared to have held the same belief. Students in Washington, D.C., they thought, had terrible outcomes because so many came from poor, African American families. In their minds, family formation, race, and poverty added up to destiny. That view had nothing to do with black-white racism; nearly all the teachers, principals, and top administrators were African American. You could have posted that sign in the central office at District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS), even outside the superintendent’s office, and not caused a stir. Even the previous superintendent publicly suggested that was true.2 In D.C., that’s just the way it was, or so they believed.

On a historical level, they were right to believe in the message that families, not schools, were to blame when children failed academically. Judged as a broad data swath, birth’s lottery—your zip code, family income, and parental education—does predict destiny with dismaying accuracy. On a comparative level, however, that destiny differs greatly. As the research for this book will demonstrate, other urban school districts with nearly identical demographics held their schools to higher standards and produced far better results.

THE JOB AHEAD

In essence, the D.C. public school system was designed more for adult employment than for teaching and learning. (Think of it as a Department of Public Works that only coincidentally involved schools.) Rhee was assigned the task of transforming those schools in only a few years—which in the school reform world translates to overnight. What happened to Rhee and her team of reformers during the first four years of their crash reforms plays out in the following chapters. The story of her headfirst plunge into dramatic school reform and the equally dramatic tale of the election three-and-a-half years later that forced out both Rhee and Adrian Fenty, the mayor who appointed her, was not the story I expected to find when I began this project. The simple narrative of Rhee versus the teachers’ unions portrayed in most of the reporting about Rhee’s time in Washington, D.C., is just that: simple. In truth, Rhee’s clashes were wide ranging and often surprising. They included The Washington Post and fellow school reformers who always said they wanted Rhee-style urban school reform but quailed at Rhee’s take-no-prisoners method.

And then there’s U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, who handed out millions of dollars of incentive grants trying to lure states into adopting the kind of sophisticated, results-based teacher evaluation system Rhee put into place almost immediately. Somehow, however, Duncan never found the time to stand by her side and show support during her tough times.3 Rhee, who never flinched when confronting the teachers’ unions, was too “hot” for Duncan’s team, which sought union cooperation.

Whose style proved more effective? Superficially, it would appear that Duncan’s style works better. Unlike Rhee, he still holds his job. But it’s far from clear that the reforms inspired by Duncan’s collaborative style—the kind where all sides settle on right-sounding reforms while praising the positives of collective bargaining—will produce striking, or even middling, results. Turning around failing urban school districts may require pushing beyond nearly everyone’s comfort zone, even Duncan’s. Michelle Rhee, however, thrives in that discomfort zone.

Finally, I quickly learned that Rhee’s campaign, despite the media focus solely on her, was truly a team effort—an unusual team effort. Ever wonder what would happen if a bunch of Teach for America (TFA) rebels with absolutely no experience running a school district seized control of one?4 That’s The Bee Eater story. This band of reformers couldn’t be more different from the usual “big man” approach to radical urban education reform, when a school district taps a retired general (or civilian equivalent) to stiffen the system with his brand of tough love. But failed urban school districts don’t need stiffening; they need to be taken apart, given a good scrubbing, and reassembled. These TFAers were willing to take on that task when no one else had the guts. Maybe they had no experience running an urban school district but they did have actual personal experiences succeeding with the kind of urban students whose education they would be overseeing. No general or admiral could claim that kind of experience.

The story behind these radical school reformers coming together as a team under Rhee to fix D.C.’s schools was my impetus for beginning this project. But that story proved to be insignificant compared to what they found waiting for them when they arrived in D.C. and the events that transpired afterward. Everyone knew the Washington, D.C., school system was among the worst in the nation, if not the very worst. But far less was known about why the system was so bad. That became apparent in Rhee’s first days on the job when she began to tour D.C. schools.

THE RACE FACTOR

In Washington, D.C.—a city that attracted thousands of newly freed slaves after the Civil War and then kept them under the thumbs of a seemingly never-ending succession of racist Southern senators who ruled over the District—no story like this is free from discussions of race. Race, from a history of racial persecution to race cards played by D.C. politicians in more recent times, has always been the city’s defining identity. Only race can explain why disgraced “mayor for life” Marion Barry remains wildly popular in Anacostia’s nearly all-black, impoverished Ward 8. Barry blames “Charlie” (whites) for his constituents’ plights; so do many of them. In part, Barry’s premise is right. Explaining the plight in Ward 8 starts with this country’s history of institutional racism. But the story behind the stall in black academic achievement in D.C. is a little more complicated and includes the patronage system that Barry helped craft, which created a schools system that was more about jobs than student achievement. But in that setup, poor student achievement had to be rationalized. And that’s why, prior to Rhee’s reforms, Ward 8 schools teemed with teachers and administrators who would have found no fault with the Slowe sign.

What was interesting about Rhee’s entanglement with D.C. race issues is how she, at least for a time, disrupted the traditional black-white plot line. Take the story of the turnaround at Anacostia’s Sousa Middle School: a Korean American chancellor hires a black principal, who in turn hires black assistant principals. Many black teachers get pushed out or fired, but for the most part they are replaced by new black teachers. Together, this team starts rescuing scores of black children from certain academic failure. The dramatic staff changes at Sousa outraged the Washington Teachers Union. But due to the school’s success, and lacking the traditional black-white political framework, the protests proved ineffectual. Think of it as asymmetrical warfare transported to school reform. It took Rhee’s critics a full two years to reframe the conflict in more politically convenient terms: Rhee favors whites. Once that storyline was established, Rhee’s fate was sealed.

WRITING ABOUT RHEE

Before beginning this book, based on what I had read in the Post and teacher-union blogs, I expected to find in Michelle Rhee a personality that would ricochet from fierce to brusque to rude. Isn’t that the persona she chose to project when posing for a now-infamous Time cover, where she wielded a broom with a no-nonsense glower? “Michelle is someone who will tell you you’re wrong and then poke her finger in your eye to make sure you know you’re wrong,” one person warned me before starting the book project. Just listening to Rhee say that everything she knows about firing people was learned from working for a Toledo, Ohio, sandwich-shop boss named “Grumpy” was enough to convince me that working for Michelle must be intimidating. (I visited Toledo mostly to meet Grumpy [see Chapter One].) But that’s not what I experienced with Rhee. I witnessed the fierceness but never saw the rude.

This book is not an authorized biography but Rhee did make herself available for interviews. In the early months Rhee and I fell into a routine: every Wednesday she visited a different school for a “listening session” with teachers—no administrators allowed—to hear gripes, requests for helps, just about anything. I would show up at her office a half-hour before she departed and then ride along, interviewing during the drive. I came to think of these as the “SUV interviews.” Stories about her early childhood in Toledo on the way to the school, stories about high school and college on the way back. If the school was far away and the traffic was bad, all the better from my perspective.

My favorite Michelle story comes from one of those trips. It was late April in Washington, D.C., right before the White House Correspondents Dinner, to which Rhee had been invited. I had been told to meet her forty-five minutes before the listening session, which I found odd, and showed up at the last minute. Bad move. I ran into her charging off the DCPS elevator with a gown on a hanger over her shoulder. “We need to stop at the tailor’s,” said Rhee. “Come along.” A few blocks away we pulled up outside her tailor. I hesitated. Should I give her some personal space and stay in the car? “Come with me, no need to waste any time.” So there I was, tagging along, trying my best to thrust my digital recorder somewhere near her lips and ask questions about her childhood as we wove through the crowds. This being Washington, D.C., nobody paid any attention.

On entering the shop Michelle switched to Korean with the tailor. Then she slipped into a bamboo-screened changing area three feet from the front door. This shop was tiny. Assuming she wanted some privacy, I backed out the door. Rhee was having none of that. “It’s okay,” she said. “Let’s continue.” So there I was, standing outside this flimsy shield, sticking my recorder through the slats, chatting about her brothers. The Korean tailor found the whole scene hilarious, as did I. But not a moment was wasted and I appreciated that.

One more thing: she looked great in that long ball gown, and with Michelle Rhee appearances matter. People pay attention when a striking woman enters a room. I saw that over and over again when Rhee spoke, unflinching in high heels and perfect outfits that looked like they must have taken days to choose but apparently are snatched up in seconds during high-speed shopping sprints. Fair or not, appearance is power and Rhee was adept at using that power.

FULL DISCLOSURE

Some author biases should be aired here. Rhee wrote the foreword for my previous book, Why Boys Fail.5 I started this book with the gut instinct that Rhee had the best shot in the nation at turning around a failed school district and I ended the book with that instinct mostly intact. Although Chapter Eleven includes a long discussion of Rhee’s faults and mistakes, I have no doubt that I will be accused of telling a story favorable to Rhee that ignores the traumas inflicted on the teachers and principals she fired. Fair enough; that’s another book waiting to be written. The Bee Eater is a narrowly tailored biography, focusing on what made Michelle Rhee into the person who stepped forward to take on the near-impossible task of transforming D.C. schools—and on whether she succeeded.

Midway through gathering data for this book I realized that the significance of what I was watching wasn’t Rhee or her band of TFA revolutionaries but rather the power of their antidote to the failures to urban education. Everything I was watching melted down to a principle I’ll call snap. It’s a term I made up, drawing on years of education reporting, my one year of actual classroom teaching (right out of college when I definitely lacked snap), and the months I spent as part of the 2009 Broad Prize for Urban Education evaluation team that visited five of the highest-performing urban school districts in the country. In these high-poverty, high-achieving urban districts, such as Long Beach, California, and Aldine, Texas, nearly all the teachers had snap—a certain quick twitch in their bodies, an urgency in their voices, and a devotion to pursuing a measurable end goal. For Why Boys Fail I spent a year keeping track of a boy at one of Washington, D.C.’s best charter schools, KIPP’s (Knowledge Is Power Program’s) Key Academy. Every teacher I observed there had snap. To teachers with snap, the message of Slowe’s hallway sign would make no sense.

Rhee had heard that Slowe message way back when she was a novice teacher in Baltimore—and rejected it. Her plan to introduce a new generation of teachers with snap to D.C. was, to use Michelle’s favorite word, crazy. She uses it to describe nearly everything. It’s crazy when she finds a principal who hides out in the office all day (and needs to be fired). It’s crazy when she discovers union contracts that force her to find positions for ineffective teachers who were pushed out of their previous school for being bad teachers. During one of our interviews I asked her to define crazy, and she laughed. “Maybe we use that word too much.” Maybe not.

As the track record will show, both in the District of Columbia and nationally, it takes a crazy person to produce results under the conditions Rhee faced. Ultimately, The Bee Eater is the story of a crazy woman taking on a crazy school system. It’s also about what it actually takes to achieve what Arne Duncan, corporate leaders, and just about everyone else agrees is not only the right goal but also the necessary goal for the future of our country: to give all children, not just those in the suburbs, a crack at the American Dream.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Several years ago when serving as president of the National Education Writers Association I played a role in creating the position of “public editor” for the organization, someone who could help education reporters cope with the dwindling education expertise at their own publications by providing assistance ranging from sources to editing. Little did I know then that one day I would be leaning on that public editor, author and former Washington Post education reporter Linda Perlstein. She combed through every word of every chapter and made me look like a better writer.

Andrew Rotherham of Eduwonk and Bellwether fame helped me make sure I got the “big picture” of Rhee’s role in the education reform movement right. The person who knows everything there is to know about the history of (mostly failed) education reform efforts in Washington, D.C., Mike Casserly from the Council of Great City Schools, steered me back in the right direction several times. Kati Haycock from The Education Trust did the same.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!