5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Gussie

- Sprache: Englisch

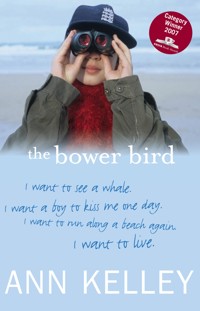

Winner of the 2007 Costa award This title continues the story of Gussie, a precocious young girl diagnosed with a rare heart condition. Despite her health problems, she is determined to live life to the fullest, experiencing typical adolescent woes such as love and strained relations with her parents. Never complaining, she offers a direct and honest insight about herself and the world around her, bringing this poignant, charming and oddly optimistic tale to life. REVIEWS 'Brilliant' THE MAIL ON SUNDAY 'I'm pleased to be able to announce that Gussie has lived to see another day with Kelley capturing so beautifully Gussie's optimism and hope.' SUE BAKER'S PERSONAL CHOICE, PUBLISHING NEWS 'The world of life and death, beauty and truth seen through the eyes of a 12 year old girl. A rare and beautiful book of lasting quality - we felt this is a voice that needs to be heard and read.' COSTA AWARD JUDGES 'It's a lovely book - lyrical, funny, full of wisdom. Gussie is such a dear - such a delight and a wonderful character, bright and sharp and strong, never to be pitied for an instant.' HELEN DUNMORE, author of 'Ingo' BACK COVER Gussie is twelve years old, loves animals and wants to be a photographer when she grows up. The only problem is that she's unlikely to ever grown up. 'I had open heart surgery last year, when I was eleven, and the healing process hasn't finished yet. I now have an amazing scar that cuts me in half almost, as if I have survived a shark attack'. Gussie needs a heart and lung transplant, but the donor list is as long as her arm and she can't wait around that long. Gussie has things to do; finding her ancestors, coping with her parents' divorce and keeping an eye out for the wildlife in her garden.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 321

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

ANN KELLEY is a photographer and prize-winning poet who once nearly played cricket for Cornwall. She has previously published a collection of poetry and photographs, a book of photos of St Ives families and an audio book of cat stories.

She lives with her second husband and cats on the edge of a cliff in Cornwall where they have survived a flood, a landslip, a lightning strike and the roof blowing off. She runs writing courses for medics and has spoken about her work with patients at several medical conferences. She also runs courses for aspiring poets at her home.

The Bower Birdis the sequel toThe Burying Beetle was shorlisted for the Brandford Boase Award and was selected for the WHSmith New Talent Initiative.

The Bower Bird won the 2007 Costa Children's Award and the UK literacy Association Book Award. The Bower Bird also won the 2008 Cornish Literary Guild's Literary Salver.

Other Books in the Gussie Series

The Burying Beetle

Inchworm

A Snail’s Broken Shell

Other Books by Ann Kelley, published by Luath Press

Runners

The Light at St Ives

The Bower Bird

ANN KELLEY

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

Thanks to Jutta Laing and the RD Laing Trust for permission to reproduce material from Conversations With Children; and to Curtis Brown, on behalf of the Estate of AA Milne, for permission to quote from Winnie Ille Pu.

First published 2007

This edition 2007

eBook 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1-906307-32-5 (children)

ISBN (print): 978-1-906307-45-5 (adult)

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-49-6

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Scottish Arts Council towards the publication of this volume.

© Ann Kelley 2007

For my wonderful family

Table of Contents

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

CHAPTER FORTY

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

CHAPTER FORTY-TWO

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR

CHAPTER FORTY-FIVE

CHAPTER FORTY-SIX

CHAPTER FORTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER FORTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER FORTY-NINE

A note from Ann Kelley

Enjoyed The Burying Beetle?

Inchworm Extract

Other Books from Ann Kelley & Luath Press

PROLOGUE

I’m not dead yet.

CHAPTER ONE

WE’VE BEEN HEREfor two weeks. I’m still not well enough to start at the local school. But the weather has been barmy – or is it balmy? Yes, it probably is balmy. Barmy means daft. The sun has shone on us most days since we moved, and I feel that my heart is going to mend enough to have the operation that could give me a few more years of life.

It’s a cold night and the sky is clear. Stars are appearing one by one. I wear my distance specs to see them otherwise it’s all a beautiful blur. I sit in my window on a stripy cushion and feel… happy.

The lights of the little town are twinkling below me, and there is a nearly full moon – its blue-white wedding veil draped across the bay. The lighthouse winks its bright eye every ten seconds.

I did have a bedside lamp on but moths kept coming in the window to commit suicide. Why do insects that choose to fly around in total darkness have a fatal attraction for hot light bulbs? They must be barmy. Or maybe a hot bulb gives off a smell like female moths and the male moths are attracted to it for that reason.

Even in the middle of the night seagulls are flying all around us, calling to each other in the dark. The wind has got up and the gulls are lifting on invisible currents and then swoop fast like shooting stars.

Our young gull is crouched on the ridge of the roof, his head poking out over the top, watching the adults and whining pathetically. There must be some juvenile gulls up there learning how to fly and land cleanly on the rooftops and chimneys, just as if they are alighting on cliff ledges.

I scrunch up under a warm woolly blanket with my feet up, and Charlie keeps trying to get comfortable but there’s no horizontal bit. She prefers me to be flat in bed so she can warm herself on my tummy, or my chest. She shouldn’t really sit on my chest as I have trouble breathing at the best of times and anyway, I had open-heart surgery last year, when I was eleven, and the healing process hasn’t finished yet. The operation was a waste of time. It was supposed to be one of three procedures to repair the various heart defects. When I was opened up they could see that I had no pulmonary artery, not even an excuse for one, and there was nothing to build on. So the surgeon just closed me up again. I now have an amazing scar that cuts me in half almost, as if I have survived a shark attack.

Poor Charlie, she doesn’t understand why I don’t want her on my chest.

I reluctantly leave the starlit night and get into my bed. I’m reading a really good book by Mary Webb calledGone to Earth. It’s about a girl who has a pet fox. Mary Webb has written several other books. I’ll have to look out for them at car boot sales or in the second-hand bookshop, as they are so old they are probably out of print.

As usual, the three cats wake me. Charlie is the noisiest and the most demanding. As soon as there’s a glimmer of daylight she starts on at me to get up and feed her. She meows loudly and jumps on the bed and marches up and down on one spot, as if I am her mother and she is trying to make the milk come. She sound quite cross. If I pretend to sleep she gets really irate. The other two are more patient but they stare, accusingly. I can feel their eyes on me. Flo sits on the chest of drawers and Rambo on the window seat.

I wake to a completely pink dawn. Outside everything is saturated with an intense rosy glow. Pink sky, sea and bay. Pink roofs, candy sand. I yearned for a party dress when I was five or six, of exactly this shade – to match my Barbie doll’s outfit.

By the time I find my specs, put on a dressing gown and flip-flops, load a film into my camera and lean out the window, the pink has paled and silvered, but the sun now hangs heavily above the dunes, like a red balloon full of liquid. One small boat chugs out of the harbour dragging a pink wake and gulls are following in a raucous rush.

I am surrounded by hungry cats. I better give in. Charlie is jubilant, running ahead down the stairs, calling me to hurry up. The others follow behind me.

I have to go to the bathroom first, and this really makes Charlie cross. She never knows whether to come in with me at this point, because she usually spends bath-time with me, but now she can only think about her rumbling stomach.

Mum is in the bathroom for longer and longer every morning. What does she do in there? She told me once that she hadn’t had a decent crap since I was born. First I screamed all the time, then as I got bigger I banged on the door and yelled. When I was a baby I screamed for twenty-one hours once – she wasn’t in the bathroom all that time, of course. She says I’m lucky to be alive as she nearly strangled me several times. Sleep deprivation makes you go barmy apparently.

‘Mum, I have to wee, I’m desperate.’

She’s looking into a magnifying mirror and doing some- thing disgusting with scissors up her nose.

‘Ohmygod, Mum, that’s gross. You’ll slice through your mucus membranes.’

‘They’re blunt-ended, Gussie. You wait until you get hairy nostrils. See how you like it.’

Hopefully I won’t live that long.

She does all this other stuff, too, to her face, plucking and scraping and applying various very expensive unguents. What a lovely word – unguents.

‘Is it worth it, Mum?’

‘Probably not, but I’m not giving up just yet.’

She’s actually quite cool looking, I think, but because she had me when she was forty-one she is quite old now. It doesn’t bother me much, but it bothers her. She’s shaving her armpits now. What a palaver. I don’t have any pubic hair yet, as I am small for my age – my heart wants me to be small, so it doesn’t have to work too hard.

‘Mum, can I help unpack something today?’

‘Yeah, why not? We’ll have a look in some of the smaller boxes from Grandma’s.’

Grandma was small and plump and she knitted and sewed, tatted, smocked and embroidered. You never saw her without something in her hands that she was working on. Their garden was a fruit bowl of gooseberries and blackcurrants, redcurrants and raspberries, loganberries and strawberries. I used to throw a tennis ball up onto the roof of their bungalow and catch it when it bounced off the gutter. Another game with the ball was to roll it along the wavy low brick wall, which went around the front garden, and see how far it would go before it fell off. I got quite good at that.

They lived in Shoeburyness, quite close to London, where we lived when we were still a family, before Daddy left.

Like me, he’s an only child. His parents, who I never met, came from this town.

Mum doesn’t have any brothers or sisters either, so I have no aunts, uncles or cousins on her side of the family. There’s only Mum now. Except that we are called Stevens and there are at least a hundred Stevenses in St Ives. I am determined to find my lost Cornish family, somehow.

Daddy isn’t being at all helpful. He keeps saying he’ll let me have his family tree, but he hasn’t even given me a leaf yet. Mum is being positively obstructive: she doesn’t want anything to do with Daddy’s family and assumes they won’t want anything to do with us. Anything Daddy related is a no-no. She has the screaming abdabs if I even mention him.

There’s a wildlife warden we met out at Peregrine Cottage – the house we rented on the cliff – who said she has some relations called Stevens, but I’ve sort of lost touch with her since we moved. Ginnie.

It’s sad how people drift in and out of our lives. Like my London friend Summer. I call her my friend, but I haven’t seen her since we came to Cornwall. Maybe now we’re settled in our own house, she will come and stay during school holidays. Or maybe I’ll never see her again.

I don’t suppose I’ll ever see Shoeburyness again. Or smell the smell of it: cockle shells and seaweed and mud. The tide comes in very fast from a long way out, where the longest pier in the world ends. The water is a muddy brown colour though, not like the clear blue-green of St Ives. But there were wooden breakwaters to climb and balance on and I liked the pebbly beach, and finding white quartz stones to rub together to make a spark. Illuminations and neon lights shone all along the Golden Mile at Southend, where we bought fish and chips. Under the arches of a bridge there’s a row of cafés with striped awnings and plastic tables and chairs set out on the pavement. Cafés with nautical names like The Mermaid, The Barge, Captain’s Table. That was where I had my first experiences of eating out: sausage and mash or egg and chips, always with a cup of tea.

Grandpop and Grandma would take me to the pebbly beach and they’d hire deckchairs and we’d have fish-paste sandwiches and apples for tea. I could still run and climb then, and I would jump from roof to roof of the beach huts. (The beach huts had names too:Sunny Days, Happy Days, Cosy Corner, Chez Nous. That’s French forOur House.)

Grandma was scandalised and tried to stop me, but Grandpop would cheer me on.

‘You can do it, princess.’

I don’t look like a princess. I am small for my age and skinny and my skin is rather mauvish, I think. My hair Mum calls dark blonde, but to be honest it’s mouse. ‘Nothing Wrong with Mouse.’

‘Oh, the elephants!’ I unpack a troupe of elephants, three of them, each one a bit bigger than the one before, all with turned up ivory tusks and mother of pearl toes. I remember them standing on a window ledge. They are made of some heavy black wood, and carved. Looking closely, I see that they are slightly damaged – a piece of ear gone here, a tusk there. I remember them as being perfect, and Grandma saying, ‘Be careful, my love.’ I used to invent journeys for them across Africa, searching for greener pastures. I imagined them as a family – father, mother and baby. That was before I learned that the bull elephant doesn’t hang around to bring up his baby. The mother has to do that on her own.

There’s a pink-brown stone Buddha too, which I always loved to hold as it felt cold even on the hottest day, as if it contained something otherworldly. It has a smiling face, as if this god has a sense of humour. You don’t get that impression about Jesus or God.

‘Where shall we put them, Mum?’

‘Have them in your room if you want.’

I put them on the stairs so I can carry them up next time I climb to my attic room. There are little piles of towels and sheets, clothes and books there already, waiting to be carried to their homes, like travellers in family groups at a bus station.

Grandpop travelled all over the world when he was in the Royal Navy and brought back lots of exotic souvenirs. We unpack a Japanese tea set they used to keep safe in a glass cabinet, thin porcelain coloured red and gold with little figures and landscapes.

‘We’ll use these,’ Mum says.

‘But aren’t they terribly precious and worth lots of money?’

‘No, it’s only Japanese export stuff. We should enjoy them. What’s the point of having pretty things gathering dust?’

Mum’s good about stuff like that. She never makes a fuss if I break something. They’re Only Things and Accidents Happen. I pick up a cup and look through it at the sun shining. It’s a lovely thing.

‘No dishwasher for these, Gussie, you’ll have to wash them by hand.’

‘No probs, Mum.’ I am learning how to speak Strine – Australian – for when and if my new friend Brett comes to see me. No Worries. Crikey.

Mum sleeps in the main bedroom, the master bedroom, or I suppose it should be called the mistress bedroom, on the floor below me. There’s a big bay window and the same view that I have, but slightly lower of course. The terrace faces south, there’s plenty of sunshine all day long, and there’s a little slab of concrete along the front path that gets the last of the sun. We sit there together on cushions and she drinks her whisky and I have a freshly squeezed orange juice or elderflower juice and we talk.

I think we talk more easily because we are not looking at each other. It’s as if we are in a car, sitting next to each other, but looking ahead, and it’s easier to say important things if you are not looking into each other’s eyes. We have our eyes closed, because the sun is still so bright, and it’s as if we are in a dream. I feel close to Mum when we talk like that.

‘Don’t you still love Daddy just a little bit?’ I sometimes ask.

‘No I bloody don’t. He slept with other women. Why should I love him?’

‘Okay, okay. I only asked.’

‘I still feel very hurt, Gussie. Bastard! He betrayed me – us. He betrayed us.’

‘Yeah, but if he wanted you to forgive him and he wanted to be with us, here, now, what would you say?’

‘Fuck off, probably.’ She sniffs. ‘Anyway, we’re okay on our own, aren’t we?’

‘I suppose.’

CHAPTER TWO

MUM HAS GONEout for the evening with Dr Dobbs – Alistair.

I’m playing Scrabble with Mrs Lorn. She is letting me win without much of a fight. Also I keep getting good letters – the high scoring C, Q and X so far. I put down all my letters straight away – QUIXOTIC, how about that! That’s got to be the best score I’ve ever had. Probably the best score anyone has ever had in the entire history of Scrabble – 72, as it was on a double word score, plus 50 for putting down all my letters at once. She’s getting all the rubbish, lots of vowels. She calls me ‘my girl’ with an extra ‘r’ in girl. Mrs Lorn has this habit of whistling when she’s thinking – hymns, mostly. Sometimes she breaks into song. I do like Scrabble. I wish I wasn’t winning so easily though. She’s so old, she has probably given up the idea of winning.

‘How old are you, Mrs Lorn?’

‘As old as my feet but younger than my teeth and hair.’

She cackles like an old witch. ‘Anyway, my girl, don’t you know it’s bad manners to ask a lady her age?’

‘Why is it? Mum says she’s fifty-two but her tits are only thirty-nine.’

Mrs Lorn screams with shocked laughter.

I like old people, apart from when they hug me or do that thing with my lips, you know, pinch them together so your mouth is an O and they make you say ‘Sausages’. Though no one’s done that to me for years. It’s a torture aimed solely at small children who can’t defend themselves. Like when they pull off your nose and show it to you and put it back again before you realise it’s only their thumb and your nose is still where it always was, in the middle of your face. You’ve got to be very young to believe that. When you get to five it’s too late, except for Father Christmas and fairies.

When I was three I can remember sitting at the window on Christmas Eve and I saw Father Christmas’s sleigh pulled by reindeer in the sky. I really believed I saw it.

It must be wonderful to grow old like Mrs Lorn and know so much and have experienced a lot of life. It must make you wise if you can remember all those things you have heard and seen and read.

There’s a old man who has three retriever dogs on leads accompanying him as he braves the roads at Carbis Bay in his electric wheelchair. He looks very heroic, as if he’s in a horse-drawn chariot or on a dog sledge. I haven’t seen him for a while, not since we left the cottage. We used to wave to him from the car but he didn’t wave back. Probably he isn’t able to. I wonder what he knows, and what he used to be before he became lopsided? And another very old man, always dressed immaculately in tweed suit and pork pie hat, straw hat in summer (Mr Dapper we call him), walks with the help of a stick all the way from Carbis Bay to St Ives and back each morning along the main road. He looks sad. Lonely. He’s a guest at an old people’s home.

Why do they put old people’s homes in out of the way places? If I were old I would want to be in the middle of things, not on the outside ready to be shoved out of life when the time came. I suppose that’s what I felt like when I was in the wilderness out at the cottage on the cliff. Apart from society. An outcast, cast away. Here in St Ives there’s human life all around me.

Mum and Alistair have come back and he’s off again, giving Mrs Lorn a lift home. She was delighted.

Mum looks flushed and smells of cigarettes and whisky and other people’s beer. Her hair looks good. Her skirt’s a bit short though. She must like him a lot.

Alistair’s not half as handsome as Daddy. Daddy looks like a cross between Keanu Reeves and Bob Geldof, but not as scruffy as Bob Geldof. Alistair looks like a Dobbin horse, with his big ears and long face and nose. But he has kind eyes and a nice smile and always wears interesting ties. It must be difficult being a man and having to wear boring suits to work. I suppose a tie is one item you can decorate yourself with.

Like the bower bird. I think they attract females by making their nests, or bowers, look interesting.

‘Bed, Gussie, Bed. Off You Go, Late. Late. Late.’

‘Where did you go, Mum? Did you have a good time?’

‘Sloop Inn. Fun, it was fun.’

‘Did you meet anyone?’

‘Alistair knows everyone.’

‘Might he know Dad’s relations, do you think?’

‘Gussie. It’s not the sort of thing you ask a man the first time he takes you out. You ask him. I’m going to bed, and You Should Too. Tired. You Look Tired.’

‘Okay, okay, I’m going.’

I take my time getting upstairs, stop halfway to stroke Flo, who is on guard on the landing. She is such a school prefect, always keeping the other two cats in order, on their toes. I would be too, in their shoes. On their toes, in their shoes… interesting, these foot metaphors or whatever. Standing up for your beliefs. Filling his shoes. Knocking the socks off… Language is interesting.

I’d like to go to a school where they teach Latin, so I could study the roots of words. The local school is good apparently, but doesn’t have Latin. I’ll have to teach myself if I really want to learn. There was aWinnie the Poohin Latin at our last house.Winnie ille Pu.

Lucus Lucubris Jorisis Eeyore’s Gloomy Place, which istristis et palustris, rather boggy and sad.

Locus inondatus– floody place.

Domus mea– my house.

What about this one!Fovea insidiosa ad heffalumpus catandos idonea(Pooh trap for heffalumps).

I wrote those down so I could remember them. They were on the maps at both ends of the book. I like maps. There are lovely maps on the end pages of the Swallows and Amazons books too.

Mum said she entered her O-level German oral exam only knowing two phrases. One of them was –Ich erkannte ihn an seinem Bart– I recognised him by his beard. And the other phrase was –Ich muss nach Hause gehen– I must go home now. She managed to incorporate both into her conversation, and charmed the examiner with her knowledge of art – there was a Pieter Brueghel print to talk about. She spoke in English for most of the time and still passed.

I don’t believe everything she tells me. She’s a dreadful exaggerator.

Mum potters about downstairs, filling the dishwasher and putting the washing in the drier. Then she comes up too, carrying her hot water bottle. She feels the cold almost as much as me.

It’s comforting having her in the room below, moving about, snoring in her sleep.

Our gulls are settled on the roof, hunkered down for the night, their heads tucked under their wings. There’s no moon tonight and it’s very cloudy. The wind is coming from the back of the house, the west, so I can open the front window without it rattling.

Tomorrow I’ll go to the library and look for poetry books. There were loads at our last place.

I wonder if I’ll ever meet Mr Writer – that’s my name for the man who owns Peregrine Cottage. Maybe he’s a murderer doing time. Or a famous poet on a world tour. He could be a bank manager, or a drug dealer, or a gunrunner. So many possibilities. Does anyone ever want to grow up to be a gunrunner or a car park attendant or a dinner lady?

I always wanted to be a cowboy until I realised, because I was a girl I could never ever be a cowboy. I was devastated that God had done this to me. It wasn’t fair.

It didn’t stop me dressing as a boy for quite a while afterwards though. I felt I had to gradually dissolve my boyhood and think myself slowly into being a girl. It wasn’t easy.

I find it hard to go to sleep sometimes. I feel it’s a waste of time, sleeping, when I could be reading or living. But then, dreaming is a sort of living, I suppose. I often have an exciting time in my dreams, more so than in my ordinary life. Sometimes in the middle of a dream one of the cats wakes me (chasing and killing something usually) and I get frustrated by the interruption. I usually forget an interrupted dream. Why is it so difficult to remember dreams? I feel cheated if I can’t remember what happened.

Last night there were two birds. One was a little white owl sitting quietly on top of the book shelf in my room. The other was a miniature rail, buff and apricot coloured with black sharp beak, black legs and wide spread long black toes. It became scarlet and emerald, and stepped carefully across my books, as if they were water lily leaves. I think there is a bird called a Jesus bird – because it looks like it’s walking on water. It might have been one of those.

My own room: I do like it. All my babyhood is on the top shelf of the large book case: faded and worn Teddy, who has never had another name; Panda, from a trip Daddy made to Germany; Nightie Dog, that used to be Mum’s and has a zip in its tummy for pyjamas; several knitted toys, including Noddy, that Grandma made for me. He’s very old and his colours have faded but his bell still rings on the end of his night cap. And Rena Wooflie, my favourite, a soft stuffed girl dog with checked dress and apron. Mum bought her for me in Mombasa the very first time we went to Africa, because I had lost my cuddly comfort blanket on the journey.

I love Rena Wooflie and she has to come with me to hospital. It’s for her sake, not mine. She gets lonely, as she doesn’t talk the same language as Panda or Teddy or Nightie Dog. Rena Wooflie and I speak Swahili together.

jambo– hello

abari? – how are you?

msuri– good

paka– cat

malaika– angel

kuku– fowl

simba– lion

nyuki– bee

kidege– a little bird

kufa tutakufa wote– as for dying, we shall all die.

That’s all I know really but I do still have a phrase book so I could in theory learn some more.

That first winter in Africa there was a family with a little boy about my age – three – and he was desperate for my Rena Wooflie. No matter that he had hundreds of teddies and soft toys, he wanted my one and only. My mum bought another one and gave it to him. Its head wasn’t at quite the same angle as my Rena Wooflie’s and he started to moan and grizzle, and he threw it and yelled, and his mother picked it up and yanked its head around and said – Is that better? And I could tell she was pretending it was her little boy’s head she was twisting, not the toy’s.

I would never abuse my Rena Wooflie.

On top of my wardrobe, looking down at me is Horsey.He was my baby walker, a horse on wheels. Mum tried to throw him away once because the metal neck pole had pushed through the straw and fur and his head was in danger of coming off. She placed Horsey by the dustbins the day before dustbin day, and then it started to rain so she brought him in again. That was years ago. He’s still here, mended of course with a new patch of different coloured fake fur. He’s part of the family now.

Noah’s Ark completes childhood on the high shelf. It was Mum’s when she was little. There are pairs of little wooden hand-painted lions and elephants, sheep and cows, hippos and zebra, and I’ve added other tiny animals found over the years – a lead crocodile, a glass cat, a wooden cat, and my favourite, a giraffe made of bone.

CHAPTER THREE

MORNINGS IN MIDSeptember smell fresher than August, and there’s lots of swirling white mist over the water, hiding the dunes and estuary. But the air is still and somehow you know it’s going to be sunny later. The heavy band of mist is chrome and silver; the clouds are the colour of lavender leaves and steamed up mirrors. The sea is hammered pewter and the low waves are mercury creeping up the beach. Where the sun breaks through, it explodes on the water in a firework burst of sparkling stars. On the other side of the bay, battleship clouds float above the dunes and hills of Gwithian and Godrevy.

September is like a wonderful monochrome photograph or the opening credits of an obscure French movie. Like the ones Daddy used to take me to.

Yesterday evening we went to Porthmeor Beach to see the really high tide. Waves clapped like thunder on the walls of the studios and apartments on the beach and rolled up and over in a constant tumult. We hung over the wall with lots of other people and watched boys and girls run along the top of the sand racing the waves and getting soaked. Most of the tourists had gone home to get ready for dinner.

It was as if the holidaymakers had been swept away and the sand wiped clean of summer. The Island (which isn’t really an island but that’s what it’s called) turned from green to orange in the setting sun. It has a little chapel on the top and reminds me of the Paula Rega painting –The Dance. Maybe it isn’t a painting. She did huge pastel drawings. Mum has loads of books on painters and we’ve unpacked some already.

Our new house in St Ives is not new new, it’s Victorian – a terraced house on three floors. I love having the attic room – I know it’s crazy for me to want to climb all these stairs, but it’s worth it for the view: right over the grey and orange roofs down to the harbour and across the bay to the lighthouse and beyond.

I have a white painted cast iron bed and a new quilt, pink and blue cotton stripes and roses. I chose it from a catalogue. It’s very girlie. Not my usual style at all.

The ceiling slopes to the roof and I have a real watercolour painting on the wall, which shows almost the same scene I see from the window but from a slightly different angle. The walls and ceiling are white and I have white cotton curtains. When the light changes, as it does all the time, the room turns blue or pink or pale green or mauve. A small roof window sheds a square of light on my bed.

On my chest of drawers there’s a photograph of Grandpop and Grandma made by Daddy. There’s also a photograph of Daddy and Mum getting married that Mum won’t have in her room, so I’ve got it. I think it’s because she doesn’t want to be reminded of how happy they were together. And there’s a photograph of our three cats lying on a sofa together – a rare event.

We are just far enough away from the main streets not to hear the holidaymakers, though we do hear the fishing trip boatman calling out over his loud speaker. ‘Seal Island. Boat leaving in ten minutes for Seal Island.’

We are close enough to get to the shops and beaches very easily. Getting back up again is another story. But I can see people coming up the hill from my window. People! It’s wonderful to be near people again. I had begun to talk to myself at Peregrine Cottage, or anyway, to the cats. There were no people to talk to out on the cliff.

I don’t count Mum of course. She’s not terribly good at talking to me, except to tell me what not to do – Don’t Overdo it, Don’t go for Walks along the Cliff, Don’t Wear that Hat – that sort of thing. I was quite ill before we left, and she was really worried about me. I think she’s happier too, now we are in the town.

I miss the badgers coming to the kitchen door for peanuts at night, and the sight of gannets folding back their wings and plunging like arrows into the sea just off the point. I miss the crickets climbing up the wooden walls, and the slowworms, which would appear mysteriously on the sitting room floor or on the doormat.

I expect the cats will soon forget all those dear little harvest mice and voles they used to kill. At least the wildlife population will increase, now the cats have left.

I hope the robins and blue-tits and greenfinches will survive the coming winter without us feeding them sunflower seeds. Maybe the owner will return from wherever he has been all these months.

Up on the cliffs we could hear oystercatchers and curlews calling to each other.

Herring gulls nest on the roof here. Or rather, they were nesting earlier in the year, and their one chick is making the most mournful noise imaginable. He hunches his shoulders so his neck disappears and he makes this awful rasping noise. I want to give him an inhaler. He keeps nearly sliding off the roof, and it’s a long drop to the garden or to the little lane behind the house. He’s flapping his speckled wings and jumping up and down, trying to copy all the other gulls that are circling the town, screaming and chuckling and murmuring to each other. They are very sociable creatures. It’s wonderful to see and hear so many of them. There’s even a pair of Great Black-backed gulls on a roof nearby.

Every roof of the little town has its own gull family who tuck themselves into valley-gutters or next to chimneys, out of the wind. They are good parents, feeding their young even when they are as big as they are and making this horrible racket. The mother or father bird lands on the roof and the chick immediately goes up to it and starts pecking at the scarlet spot on the beak. The parent eventually throws up – that’s what it looks like – regurgitates the food for the young bird to eat.

It’s wonderful to be on the same level as the nesting birds and to watch their everyday life. The male is larger and more powerful looking than the female herring gull, but they both have a vast vocabulary. They seem to communicate in all sorts of ways. They have a companionable chuckling call, a loud angry screech, a mewing, sad, lonely call and sometimes you hear them grumbling to themselves while flying. Our parent gulls get really angry and throw their heads back and scream a warning if others try to land on the same roof.

Most of them have left the summer nests on the roofs now, but our gulls have to hang around a while longer until their offspring has learned to fly. He must have been a late summer baby.

Like me.

Mum is unpacking our stuff from London that never got unpacked at our rented place. She insists I rest every afternoon, so that’s why I am up here and she is downstairs. I can hear her singing. She must be feeling happy. I hope so.

Mrs Lorn is helping out with washing the crockery. There are newspaper words over every plate and cup. I think we should leave them like that to make mealtimes more interesting but Mum insists they are washed. Mrs Lorn is whistling loudly, like she does. We sort of inherited her from Peregrine Cottage. She’s Mr Lorn’s wife: he was the gardener there. We don’t need a gardener here. The garden is Not Big Enough to Swing a Cat in, but there’s a washing line and a little square of grass, and a pretty fence that looks like it should be metal but it’s wooden. The wooden gate (which also looks like it’s made of metal) opens onto a path, which goes along the front of this terrace and reaches a dead end after number nine. We look down over a steep little hill over the harbour and town. I think it’s perfect.

Mum bought the house while I was being ill. She had been looking for months for the right property in St Ives. I was desperate to get into the town so I could make friends and get about more. I am quite recovered now. Or rather, I’m feeling much better than I was a few weeks ago.

Actually, I am waiting for a heart and lung transplant. I can still get around, more or less, but I get very out of breath and go rather bluer than normal. Not that it’s normal to be blue, just normal for me. The hill is a challenge, but there’s an old bench halfway up, and I can always sit on the steps when I need to.