Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Children's Books

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

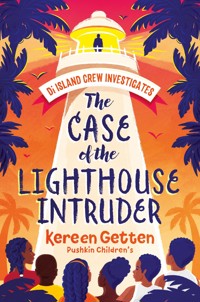

- Serie: Di Island Crew Investigates

- Sprache: Englisch

Fayson has always wanted to be a detective. When her cousins recruit her to their top-secret gang on the island one summer, her dreams seem to be coming true. But the Greatest Gang of All Time don't live up to their name, and keep getting distracted from missions by things like food, falling asleep and a fair bit of squabbling!Guided by her favourite mystery novels, Fayson takes charge and tries to track down clues about the strange shadow that has been appearing in the island's lighthouse. With tensions stirring within the gang, can she use all her smarts to solve the case?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 151

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Chapter 1

Fayson Mayor, the twelve-year-old FBI agent, has been recruited yet again to save the world. It’s getting exhausting, as she has only just stopped a major assassination plot against the King of England.

“I’m tired of fixing your mess,” Fayson says down the phone to the FBI head of division. “I’m not a robot. I need time to be a normal person, just for a day.”

My phone starts to ring for real, and I jump out of my make-believe game and check the number on the screen. I stare at it in disbelief before putting it to my ear and answering hesitantly.

“Hello?”

“Fayson! You have to come to our holiday house for October half term. It’s on a spooky island!” my twin cousins tell me, through rushed voices. They always talk over each other like it’s a race to see who can speak the fastest.

I haven’t heard from them in at least a year, so I’m shocked they’re calling now.

“Yeah, weird things happen, like ghosts and flashing lights and stuff,” one of them says, while the other makes ghost sounds down the phone for effect.

I try to identify who is speaking, but it’s hard to distinguish between their voices right now. When we were younger, I could just about tell them apart because Aaron was taller and Omar had a dimple. Over the phone they sound the same, and it’s been so long since I’ve seen them in real life.

I’ve caught glances of their holiday photos over Mama’s shoulder when she stalks their mother’s social media page. She mumbles, “I suppose I better say something before dey accuse mi of being jealous,” before commenting on their photo, typing That’s nice with a laughing face that she thinks is a happy face.

“Not that one, Mama,” I have to keep correcting her. She will pull a face and say, “But dat one mek me look like me a grimace and I don’t want dem to know what I am actually thinking.”

Mama and her brother, Uncle Edmond, haven’t been close for a while, but I think that maybe it’s because he is never in the country and Mama is always working.

Now the twins are on the phone telling me about some island where they have a holiday home. Their father, Uncle Edmond, is a hot-shot businessman and their mother, Aunty Desiree, is a lawyer. They’ve always lived rich. They have a big house in the city too, with maids, and used to invite me to stay with them in the holidays, until they started travelling abroad.

Now, out of the blue, they’re asking me to come and spend the holidays with them. I’m surprised they still have my number, with all their new rich friends around the world.

“I can’t. I don’t have a passport,” I tell them, because I don’t trust them. All they’ve ever done is play tricks on me.

There’s snorting down the phone.

“What she say?” Omar (I think) says from the other end. Aaron repeats what I’ve said and they both dissolve into hysterical laughter.

“I don’t see what’s so funny,” I snap down the phone. “Not all of us have passports to travel the world!”

“You don’t need a passport,” Aaron says, still snorting. “It’s off Portmore.”

I frown. “In Jamaica?”

“Yes!” they both shout. I still don’t believe or trust them, so I say I’ll think about it, and also I want to get off the phone because I don’t appreciate being laughed at. I have better things to do, like save the world.

“Your mother already said you can go,” Omar says. Which catches me off guard; Mama hasn’t said anything to me.

“I said I’ll think about it,” I snap, and end the call. I collapse on my bed and stare at the ceiling, thinking about what they’ve said. An island that’s not Jamaica but part of Jamaica? It’s probably filled with posh houses with servants and pools, just like the twins’ house in the city. I would feel out of place there. I am so different from all that.

Mama and I live in a small apartment on the top floor of a two-storey building not far from her work at the hospital. Our apartment faces a busy road, but across from that road is the library, my second home, so things are not that bad.

Mama works long hours and Ms Lee, an old lady from the apartment below, is always here watching me until she gets home.

Sometimes Mama will get home for dinner, sometimes I am woken up to her thanking Ms Lee in a hushed voice. Sometimes there are days when I don’t see her at all.

Tonight is one of those evenings when I haven’t seen her, but I stay awake by reading one of the books I borrowed from the library, even though I’ve read it three times already. I turn the light off, so Ms Lee thinks I’m sleeping, and read under the covers using the torch from my phone.

It is well past eleven o’clock when I hear the key in the lock: the familiar sign that Mama is home. There is a quiet exchange between her and Ms Lee. I feel a surge of excitement to hear her voice. Knowing she is home safe, and her comforting tone, usually send me to sleep.

This time I wait until I hear Ms Lee leave, then I open the door a crack and peer into the living room. As I do, Mama collapses into the green sofa with a sigh, dropping her handbag on the floor and starting to peel off her work shoes.

I pad barefooted into the room, and I am standing in front of her when she opens her eyes. She jumps when she sees me.

“Lawd have mercy!” she cries, with her hand pressed against her chest. “Fayson, what are you doing out here?”

“Mama, yuh tell the twins I must go and spend the October holidays with them?” I ask.

She takes a breath and looks at me. “You don’t want to go?”

I shake my head adamantly. “I don’t have anything in common with dem. They too rich and they play too much tricks on me. I don’t like dem.”

She stifles a smile and gets up, walking over to the open kitchen that is part of the living room.

“Well, first of all, I didn’t tell them anything. They begged their mother to ask me.” Mama switches on the kettle. She mumbles something under her breath about her brother getting someone else to do his work, but I barely catch it and she turns her back on me when she says it.

I look up at her. “Why dem do dat?”

She shrugs, reaching for a cup in the cupboard. “Maybe they miss you.”

I know that’s not true. Not with all their rich friends and travelling the world. If they miss anything about me, it’s throwing spiders in my hair and putting water in my bed to make me think I’ve wet myself.

“But why did you tell them yes, when you know I don’t like them?”

She laughs. “Fayson, you don’t like nobody, and that’s the problem.”

I pull up a seat at the breakfast bar and lean on it. “Why is that a problem?”

Her smile fades. “Because ever since Lizzy left, you don’t talk to nobody. And you need friends.”

A picture of Lizzy, my best friend, flickers through my head. We did everything together, until she moved to Kingston with her family. Now it’s just me saving the world alone.

“I have friends,” I tell her, and I start to reel off the characters in my latest book:

Hazley the detective and her dog Barnaby, who is always by her side and may as well be by my side because he feels like my dog too.

It isn’t until I mention the robot Herbert that she realizes what I’m talking about, and the hope in her eyes diminishes like I just told her she won a million dollars and then took it away.

She pours herself some camomile tea, because it helps her sleep. “Real friends,” she says, glancing up at me, “not pretend ones.”

“They’re real to me,” I say, feeling offended.

She shakes her head. “It’s either spend half term with the boys or go to church camp again—if they let you in.” Mama throws me a disapproving look.

I lower my eyes, remembering how I asked so many questions at the camp—like where in the sky God was, if they had a map they could show me, and why astronauts haven’t found him yet—that they called me ‘disruptive’ and told Mama to come pick me up.

She looks at me gravely. “We lucky to get any of these opportunities, Fayson. You can’t keep sabotaging them, because I don’t have no money to pay somebody to look after you.”

“We can go somewhere,” I suggest. “You and me.”

“I have no money to go nowhere,” she says tiredly.

“Or we can go to the beach and get ice cream?”

“Which part of ‘I don’t have no money’ you not getting?” she snaps.

My heart sinks, and the room becomes heavy with silence.

Mama’s shoulders fall and so does her head. “Look,” she says in a strained voice. “I would love to do all dem things with you, but I need to work. I can’t afford to stop working, so this is what we have—church camp or your cousins. You need to pick one, or I will pick one for you.”

Through the dim light of the street lamp shining into my room, I lie in my bed thinking hard about what Mama said. I think about how she works long shifts, six days a week, with only one day off and that day is busy with running errands. I think about how I follow her around to the bank and the supermarket, to the doctors and the hair shop, on that one day, because it’s the only time I have with her.

I think about how we stop off at the patty shop and get my favourite coco bread and patty with fruit-punch box juice. Then sit outside on those iron chairs that are not very comfortable and watch people go by under the harsh heat of the afternoon sun.

I think about how quickly that day always goes and how, before I know it, it’s nighttime and Mama is getting ready for work again. I think about how tired she suddenly looks when she is ironing her uniform and how much it hurts knowing we won’t get this time again for another week.

That’s what I hate about church camp. They take us so far into the Blue Mountains that I don’t even get that one day with her. I don’t see or speak to her for three whole weeks, except for one phone call.

I think about the strict rules the camp has on not contacting home too much, early bedtimes, and annoying group activities that make me want to vomit.

I roll over on to my side and reach for my phone. I dial the last number, knowing Mama only gave me enough credit to call her in an emergency, so I hope this call isn’t a waste.

“Yo,” Aaron answers on the other end. “What time is it?”

“I’ll come,” I tell him. I can hear him rustling around.

“Really?” he says excitedly, and I can just picture all the pranks he’s coming up with in his head right now.

“On one condition…”

“Okay, what is it?”

“You give my mother a job, on your island, for half term.”

There is silence on the other end.

“You hear me?” I demand.

“How am I supposed to give your mother a job?” he asks. “I don’t own the island.”

“Talk to your parents, or your friends’ parents, or whoever. But I’m not coming without her. Got it?”

I hear a sigh down the phone. “Okay,” he says, “I’ll talk to my parents.”

I nod. “Good, then I’ll come.”

Chapter 2

When I enter the living room for breakfast, Mama is rushing around as usual—but this time she seems more irritable.

“Sit down and eat your food before it gets cold,” she says, and turns her back on me to pack her lunch of corn beef and rice. I slide into the seat at the table feeling like I have done something wrong but not knowing what. She packs her lunch in her bag and makes her way over, sitting down across from me.

We eat in silence as the TV plays the news in the background. Outside, the road is already busy and cars whizz past beeping their horns at each other. There is a palm tree in our parking lot that is so tall I can see it framed by the window, its leaves swaying slightly under the morning breeze.

“Mama, did I do something wrong?” I ask eventually, unable to take the silence any more.

“You didn’t do anything wrong,” she says, without looking up from her tea. Then, as if she changes her mind, she places the cup down and glares at me. “Why you think I need you to find me a job?”

I look at her, confused.

“And with my brother!” she says, shaking her head. “You think I want to beg a job from my brother?” Then it clicks: my conversation with Aaron last night.

“I really wanted us to spend October half term together,” I try to explain.

She shakes her head. “How many times, Fayson? I need to work.”

“But if you work on the island, we can see each other,” I tell her. “We can see each other every day, and because it’s family, they might not even make you really work—just, like, sweep the floor or something but still pay you.”

Mama looks at me quietly, her eyebrows wrinkled. She shakes her head slowly. I don’t know what I’ve said now to make her sad, and I try desperately to think of what I could have said wrong.

“You think I should sweep my brother’s floors?” she asks quietly.

My mind races. Is that wrong? Should I apologize? I don’t want her to be mad at me, in case she sends me to church camp instead.

“You think I should give up my job as a nurse to sweep my brother’s floors?” she repeats.

My heart falls into the pit of my stomach. I didn’t mean that. I didn’t mean she should only sweep floors. I go to tell her that’s not what I meant, that all I wanted was for us to be together, when there is a knock on the door.

She pushes her chair back and walks across the tiled floor to open it. Ms Lee is on the other side.

“Good morning,” she says cheerily.

Ms Lee is a retired teacher. She runs a group that is always organizing town meetings and baking cakes for the ‘less fortunate’. She always tries to get Mama to join her group. Every day Mama promises her she will, but she never does.

Mama steps to one side, forcing a smile. “Good morning, Joanne. Come in,” she says with a tired voice.

Ms Lee steps into the apartment with her usual big woven bag that will be filled with food even though Mama keeps telling her we don’t need food, we have enough.

But we don’t. We never have enough.

Mama disappears into her room while Ms Lee enters the kitchen and starts to unpack her bag, showing me everything she has brought. “And your favourite,” she says, showing me a bag of tamarind balls. Normally that would excite me, but all I can think about is Mama being upset with me. I get up from the table and walk over to her bedroom, where I listen with my ear against the door to see if I made her cry. I can’t hear any crying, so I knock gently.

“Come in.”

I open the door and Mama is sitting on the edge of the bed, in front of her long mirror, taking the rollers out of her hair. She looks at me through the mirror.

“What is it, Fayson?”

I slide against the wall by the door with my hands behind me. “I will go to the island with my cousins,” I tell her, even though my heart is heavy. I stare at my feet, so she doesn’t see how sad it is making me to say it. “I will go by myself.”

When she doesn’t answer, I look up. She brushes her hair, then grabs her bag and heads to the door. She stops as she reaches me and kisses me on the forehead.

“Good,” Mama says, “I’ll tell them you’re coming.” She walks by me, then stops and lays a hand on my shoulder. “From what I hear, you won’t even want to come back.”

Then she is gone.

I listen as she tells Ms Lee goodbye and thanks her again for watching me. I hear the door open, then it closes, and I wish it wasn’t like this. I wish Mama was as rich as her brother and we had an island we could go to.

Just me and her.

I wish good things happened to us the way they happen to my cousins all the time. I wish I had all the wishes in the world, and they would come true.

A week later I sit on the balcony outside our apartment, waiting for the twins to come and pick me up. They are due any minute now but Ms Lee has sent me outside so she can clean the floors. The front door of the apartment is open, and she is playing some old-time music and humming along to it.