Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

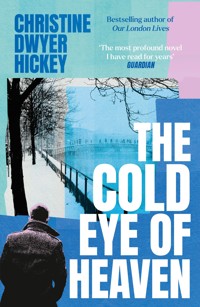

Winner of the 2012 Kerry Group Irish Novel Award The Cold Eye of Heaven: the stunning new novel from Christine Dwyer Hickey, bestselling author of Last Train from Liguria. Farley is an elderly Irishman, frail in body but sharp as a tack. Waking in the middle of the night he finds himself lying paralyzed on the cold bathroom floor. And so his mind begins to move backwards, taking us with him into his past. As Farley unravels the warp and weft of his life, he relives the loves, losses and betrayals with the darkly comic wit of a true Dubliner. For this is also Dublin's story, the city Farley has seen through poverty and prosperity, boom and bust - each the other's constant companion throughout his seventy-five years. Epic in scope, rich in detail, and shot through with black humour, The Cold Eye of Heaven is a bitter-sweet paean to Dublin and a unique meditation on the life of one of its citizens.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2025 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Christine Dwyer Hickey, 2011

The moral right of Christine Dwyer Hickey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 80546 440 2

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 416 8

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground Floor, 71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland. www.arccompliance.com

Praise for Christine Dwyer Hickey:

‘One of Ireland’s most lauded modern writers’ Daily Mail

‘A national treasure’ Paul Lynch

‘A talented and original writer’ Irish Independent

‘Christine Dwyer Hickey writes such beautifully poised prose’ Graham Norton

‘Hickey’s writing is gorgeously lyrical’ Sunday Business Post

‘Christine Dwyer Hickey is nuanced and exceptional at character and voice’ Sinead Gleeson

‘Everything about the writing is so carefully balanced – thought and action, feeling and movement, drama and suspense. She leaves space on the page, giving her characters the freedom to behave unexpectedly and to occupy the mind of the reader even when they are offstage’ Irish Times

Also by Christine Dwyer Hickey

Our London Lives

The Narrow Land

The Lives of Women

Snow Angels

The House on Parkgate Street and Other Dublin Stories

The Cold Eye of Heaven

Last Train from Liguria

Tatty

The Gatemaker (The Dublin Trilogy 3)

The Gambler (The Dublin Trilogy 2)

The Dancer (The Dublin Trilogy 1)

*

Christine Dwyer Hickey was born in Dublin and is a novelist and short story writer. Her recent novel The Narrow Land won two major prizes: the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction and the inaugural Dalkey Literary Award. In 2020 her 2004 novel Tatty was chosen for UNESCO’s Dublin: One City One Book, having been previously longlisted for the Orange Prize. In 2012 The Cold Eye of Heaven won the Kerry Group Irish Novel of the Year. Her work has been widely translated into European and Arabic languages. She is an elected member of Aosdana, the Irish academy of arts.

For Desmond, with love

The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse

– The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused – nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Philip Larkin, ‘Aubade’

Tak, tak. Zaden, zaden.

15 January 2010

FARLEY IS AWARE OF a blur in his right eye. A bauble of light in the darkness. It fills up, then drains off. Every few minutes it does this – as if he has his own little cistern inside his head. A recurring blur. He chances a couple of words: hello, then blur. He tries them again – nothing. And so he begins to take stock. It’s the middle of the night, he’s in the jacks – one side of his face shoved into the linoleum, right shoulder pressed into the radiator. His nose is a few inches from the pedestal of the toilet, and his body, in an awkward curl, lies in the space around it like a dog that’s outgrown its kennel. He may have fallen and broken something – that could be it. But there’s no pain. There is no feeling at all. He remembers the dark space of a dreamless sleep. Otherwise nothing. It’s as if he was born here, with his face nuzzled into the bowl of this jacks.

The thing to do now would be relax. Just relax. Not to go thinking the worst. Get the mind steady before thinking at all. That would be the thing to do now. Like that time years ago, when he fell off the boat into the Shannon. Young then, not that long after he’d started working for Slowey, in fact. The middle of winter, a sparkling cold day, he’d been dressed in thick jumper and boots. Not much of a splash when he fell overboard, down between the side of the boat and the slimy dock wall. The sensation of the water suckling on him. Nobody had been able to believe their eyes when he bobbed back up, un-fucking-drowned, as they had all kept saying later in the pub – unfuckingdrowned! And why was that? Because he’d refused to panic. He had surrendered to the water, let it pull him all the way down. And then, as if it had just got fed up with him, it had spat him right back up again. Slowey had often mentioned it after; at the Christmas do or other speechy occasions: ‘And from that moment on,’ he’d say, ‘I knew our man Farley was a survivor. Not even the Shannon could keep the bastard down!’

Farley takes in a deep breath. That’s it – relax. He has a feeling he has to be somewhere tomorrow, or – depending on what time it is now – that could be today. Somewhere important. He seems to remember collecting his suit from the cleaner’s anyhow, soft in its cellophane wrapper. And the girl behind the counter with the eyes like a goat. The heat and hiss from the machines behind her. The little moustache of sweat on her lip and how it had crossed his mind that he’d love to lean across the counter and lick it clean. And how shot through that thought had been smaller threads, like was it normal for a man of his age to be thinking that way? And if it was, should he be proud of himself or ashamed? He can remember all that now. But the reason for needing a clean suit?

The dark. The dark still holding the room. Through it he can smell the toilet; layers of old piss-splashes around it. His splashes – it would have to be – no one else had used this toilet in years. It consoles him to know this – he never could bear the stench of the herd. As far as he recalls, the last time a stranger would have used this room was the day of Martina’s funeral. Thirty odd years ago that would have been. A queue halfway down the stairs then. Men only. Ladies had to go to the house next door. A sign on the gate had told them so: ‘Ladies This Way’ with an arrow pointing at the house of – whatever this her name was. Brown eyes she had in anyway. She’d made the sign herself, knocking in first thing to show him. ‘Martina would have preferred ladies to have their own facilities,’ was how she had put it. And Farley, on the morning of his wife’s funeral with rolled-up shirtsleeves, one hand tucked into one half-polished shoe and a blot of tissue on his chin where he’d cut himself shaving and a grin in his eyes from something he’d been listening to on the radio, had opened the door without thinking. For a few long seconds he’d stood gawking at the sign, wondering what he was expected to say. Until Mrs Brown-eyes had finally prompted, ‘Ah, you know what she was like.’ And Farley then duly responded, ‘O God, yes I do.’

By the end of the night the sign for the Ladies had fallen on the ground. Slowey’s big brown brogue stamped on it as he stood with Bren Conroy waving a sombre goodbye. As if they weren’t going to sprint down to the County Bar for last orders, the second they got round the corner. Nowadays people don’t hang about at funerals. Nowadays, they say their piece and scurry back to work. Except those with nothing better to do; old folks or garglers glad of the excuse. You’d even see some dressed in tracksuits and trainers. Conroy’s son, for example, a few months ago. Turning up to his own father’s funeral with his junkie pals in tow. The bony hand when you shook it, the old woman’s voice when he accepted condolences, the swivel eye. Better no son than the likes of that.

Farley regrets. What? He isn’t quite certain. It could be that he hadn’t thought to turn on the light before stepping up to the toilet. It could be something more distant. But he can see all he wants to see for the moment by the light of a lamp post outside; looking in at him like the cold eye of heaven.

The outline of the bathroom around him; the hump of his dirty laundry; the dressing gown, ghoulish on the back of the door. The murky long mirror. And what good would a full 60-watt be to him now? What could it show him? Ancient bottles of shampoo and other squirty stuff that’s been lying there for years? His reflection in the bottom of the mirror? A wall of white tiles like a cul-de-sac to the imagination? At least the dark allows him to wander.

His headache resumes. He feels it like a red-hot bulge in the corner of his head. His thoughts return to Mrs Brown-eyes. He wonders why. Why he should keep thinking about the oulone next door? A woman he hasn’t seen these years. Not dead though, not so far as he knows. But in a nursing home someplace. The house let out by her grown-up children, to foreigners. He realizes then, it’s not the woman he’s been thinking of, but the house she lived in. The house next door. Ah right.

For a moment Farley can see her kids. Three of them; standing on his doorstep with cards in their hands, looking to be sponsored for something or other. Plain, timid, little things, rigid in their clothes, always looked like they were coming from Sunday Mass. He’d had a few jars on him, tried being friendly, saying the sort of things he thought you were supposed to say to kids. About school and Santy and how old are you now?

Pardon? They’d said pardon a lot.

Martina used to love buying them presents. Pencil cases in September, masks at Halloween, selection boxes at Christmas. Seasonal stuff. She seemed to get a kick out of doing that. He’d never say but he’d often felt it made her look a bit needy.

He tries to remember the man next door. The father of the three little stiffs. The husband of Mrs Brown-eyes herself. A little chap. Tight arse running for the 79a bus, holding the button of his jacket into his belly. He can see the most of him, the knob of his elbow, his little shoes rising and falling as he trots along, his little grey suit even. But the face?

His own father comes into his mind then. Face unfortunately clear. Died of a stroke, or six months after a stroke, though the stroke was the cause of it. A surly bastard anyway, who hadn’t time or a word for anyone. A snarler. He’d snarl at his newspaper, snarl at the radio, snarl if you spoke to him while he was having his dinner. Yet anything like the crowd at his funeral. Standing room only. People his mother had never seen or even heard of before. Later back in the house one of them had made a speech, clipping his whiskey glass for order! Order! Farley and his brother left looking at each other. It was like he was talking about a man they had never met – a raconteur. A wit. A great family man. An honour to have known. A pleasure to have worked with. A fly-fisher.

Farley listens to the beat of his heart. The only thing of movement or sound in the bathroom. A good strong beat, not too fast, maybe a bit on the slow side. The headache has subsided again. Not gone, just taking a little breather. He pictures it like a big thick tongue, hanging over a rock, heaving.

His father had worked as some sort of court clerk, a runner for a judge or a barrister maybe. Farley never knew much about his job, beyond the fact that he’d hated it. And he only knew that because any chance his father got, he reminded them of the fact. No matter what childish gripe you’d come up with; going to school in the rain, or out to the shed in the dark for the coal, he’d come right back at you with his – and what about me? How do you think I feel? Do you not think I’d rather be elsewhere, doing elsewhat? Instead of going into that kip every day. I hate that bloody job. Hate it! Hate it! But then his father had hated most things. Except for flyfishing. ‘The love of his life,’ his mother used to call it, with a look on her face Farley had never quite been able to read.

He’d be gone for the day. Sometimes a weekend. Loading up his fishing gear first, wrapping up sandwiches he’d made himself, while Farley looked on and tried his best not to whinge; ‘Ah Da, you promised me, you did.’

Farley sees his young self for a moment, clutching the bars of the garden gate, with his brown hair and sticky-out ears, like a little monkey in short pants, bawling his brains out. The sound of the old Morris tittering off up the road, rods sticking out the rear windows, wobbling goodbye. And his mother waiting with a biscuit in one hand and the corner of her pinny in the other, ready to wipe his eyes. ‘Ah, he’ll bring you, another time. Didn’t he promise, he would? There, there now, you’ll be grand.’

Back in the house, she would sigh into the kitchen, a warm sunny sound, pressing her hands down on the draining board.

The love of his life.

His brother had been indifferent to it all; what do you care where he goes or what he fishes? And he didn’t care, not really. He’d just wanted to see what his father was like, happy. And the sandwiches of course. He was curious to see what sort of sandwiches a man like his father might make. By the time he was eleven he’d stopped asking to go. By the time he was twelve the promise had slipped from everyone’s mind. Soon enough after came the stroke.

Farley decides to stop thinking about his father. To concentrate instead on a plan. A strategy – that’s what he needs. He knows he can’t move. That every bone, every inch of his flesh is locked into the floor and that he’ll have to rely on his voice. He’s confident that there’s plenty still in there. It just needs a bit of a rest, that’s all. The thing to do would be to wait. Allow the energy to recharge of its own accord. Let it gather and thicken. That would be the thing to do now. When it gets bright, or almost bright. When the youngone from the house next door goes to take her bike out of the shed. That’s when he’ll let it go. Then.

The house next door. The youngone living there now. The tenant. That’s right. An early riser, thankfully. A busy, early girl. Off every morning to work in the fish market except Sunday and Monday. He often wonders how she survives down there with her pointy face and dainty ways, in among all those targers. Sonya – was that her name? Sonya or Sofia maybe. Silvia, that was it. From Poland anyhow, or one of those places.

The minute he hears her. Whatever strength he will have managed to save up by then, he’ll muster it up, give her a roar. He wonders how many times he’ll need to call out? A few times, probably. He’ll have to ration himself so, not throw it all out first go.

He imagines her now, unclenching her bike from the other bikes in the shed, and drawing it towards her. Then pushing it a little way up the garden path, a strip of white polyester from her overalls showing under the hem of her green tweed coat. Her wellies in the basket, the Fagan-style gloves on her hands with her little pink fingers poking out. He imagines her stopping just before the side entrance. Cocking up a delicate ear – what? what was that? – reversing her steps and the wheels of the bike. She’ll frown. Then listen again. She might think she’s imagined it. In which case she’ll have to call on her housemates for verification. Three Polish blokes coming out to the garden then; tall, high-arsed, fairish. A touch of the Luftwaffe about them. ‘What?’ they’ll say. ‘What?’ (or whatever the Polish equivalent would be). ‘Where? Up there? I can’t hear no thing. Are you sure? Are you certain?’

He’d have to be ready for round two then, just at that precise moment to collect, aim, and fire: ‘Help…’

And she’d go, ‘Now – hear it now?’

‘Ah wait now – yes. Yes, yes.’

‘Tak,’ they might say. (He thinks that could be Polish for yes.) He seems to remember she told him one day across the back garden wall. Tak is for yes, zaden – was it? Zaden means no. Or maybe it was the other way round.

Farley knows that it must be freezing. A sugary frost on the window-pane, a scrap of old snow on the cill. He should be freezing all over. He should be able to feel the radiator like a block of ice behind him. But he can’t. Only on his left side can he feel anything, where the cold is lifting the skin from his flesh. The right side doesn’t even notice. It’s as if half of him has been cut away and moved to another room. More than anything else – the headache switching on and off; the recurring blur in his eye; the refusal of his voice to come out of its box – it’s this uneven distribution of cold that gets to him.

He brings himself back to the matter on hand. The Polish bird – yes. She leaves around six. Unless it’s a Sunday or Monday when the fish market is shut. But it can’t be Monday if he collected the suit yesterday because the cleaner’s doesn’t open on Sunday. But it could be Sunday, in which case he’s fucked. But he won’t think about that, it could be any day as far as he’s concerned, except Sunday or Monday. So – she’ll leave around six. And she’ll hear his call and she’ll bring the Luftwaffe out to the garden. The Polish blokes, being blokes, will be reluctant to intrude. They’ll have to stand in a circle and have a discussion. They’ll probably have to have a cigarette to help the discussion along. Tak, tak. Zaden, zaden. Should they call the police? Should they kick the door in? Get a ladder and look in the window? They won’t want to involve the police. One of them might ask if she has a key to his house. Then she’ll have to explain herself. At this point he could try sending down another shout.

Tumbling ashes. Soft grey light hatching out of the darkness. Farley notes the sudden rush of wind outside, the swish of the trees. He listens for sounds of traffic from the Kylemore Road. A squawk of a near-empty bus, the infrequent snore of a car, a motorbike’s buzz. In between, the long silence. For a minute he thinks he’s in his grandmother’s house, the house where he spent so much of his childhood. Bang up against the wall of the Phoenix Park. When he was a boy the silence never seemed complete. You’d always hear something. Owls or other nocturnals, horses neighing from the army barracks up the way. Even the night sounds from the animals in the zoo. A lonely sound that. It used to make him fret, the thought of an animal howling alone in a cage, no one to heed or help it. He used to have to go to sleep with his pillow over his ears. But he’s in a different house now. The house of his adulthood. Another area altogether. For all he knows they’re still howling in their cages.

His headache is back, in full form now, pushing to break its own record. Farley feels the bulge rise and expand, rise and expand. A little stronger each time, a little hotter. Lava.

*

He opens his eyes, the light has lifted again, and he thinks he may have passed out for a while and if so, wonders where to and how long he’s been gone. Then he wonders about the state of his pyjamas. Whatever way he has fallen, the top has risen and rolled under his arm. He knows this. But he can’t remember when he last changed the bottoms and hopes the brown streak up the inside is a memory from a different pair, on a different occasion.

A day last summer comes back to him. The Polish girl hunkered down in the garden, hacking something out of the ground. He’d been busying himself in the shed, keeping an eye on her through the little window. Her dress had been flowery, her shoes made of rubber and he’d been thinking to himself how old-fashioned these people were, with their vegetables in the back garden and their cycling everywhere and their knitting and their second-hand shops where they buy their flowery frocks. Nothing wasted. Like people you’d see years ago. Or people during the war. When he came out of the shed, she had looked up and smiled at him. Then stood and came over to the wall for a chat. She was going later to have a picnic in the Park, near the Furry Glen. And that had seemed so old-fashioned too, a picnic in the Park, something he hadn’t seen anyone doing in years. She’d been picking radishes to bring. ‘Look,’ she had said, holding the bunch up, fresh clay dribbling out of it. ‘Everybody, they bring something. I have also a bread I make this morning and chocolate I buy in the new Aldi store.’

He had liked that she told him all that.

Then she had asked if he had plans for the weekend himself and for some reason the question had embarrassed him. ‘Ah you know,’ he had shrugged, ‘just the usual.’ And she had cocked her head at him as if she expected more. As if she expected him to explain what ‘the usual’ meant.

‘Well, good luck now, enjoy the picnic,’ he had said and began to walk off, afraid that she might think he expected, or even hoped, to be asked in for a taste of her bread.

She had called after him. ‘I just wanted to say, if you want you could. You know, give me a key, in case maybe there is ever—’

‘Sorry?’

‘In case you have. Or you need. If I have your key then I can? In my country is usual when an old person is a neigbour…’

For some reason the suggestion had winded him. He hadn’t been able to think of a way to respond, so he just looked at her. And then began to step back.

‘Does that mean you don’t want to give me the key?’ she asked, her face colouring up.

He turned his back to her and kept walking until he was inside the house again, the door closed behind him. He’d been offended. But more than that – he’d been hurt. Hurt and even humiliated. Why though?

Because he had looked over the wall at an old-fashioned girl and liked what he’d seen? Because the truth was he’d had a little smack for her? Not that he would have expected or even wanted anything to happen. He had just liked having the possibility there on the air over the wall, between the two houses. Not that it had made him feel any younger, just a little less old.

Almost light. He can see more clearly now, the rusty bolt that fixes the toilet to the floor, and the white porcelain rise of the bowl’s exterior, like a dowager’s throat. He can see the pallor of the tiles on the wall, the faded beige folds of his dead wife’s dressing gown on the back of the door. And the architecture of himself in the bottom of the full-length mirror on the wall beside it. He follows the curves and angles; the sole of his foot to the cap of his knee, above it a length of thigh. The bottom of his pyjamas are slightly down, flap wide open. It takes him a moment to understand the grey fleshy bloom lolling over his groin and inner thigh. He draws his eye upwards, sees an elbow, a part of a grubby vest, the tip of one shoulder. The jaw then, which looks broken and twisted off to one side. The view from the mirror shows one eye. It blinks at him, then blinks again.

Farley listens. There’s a click from the side gate of the house next door. Footsteps. Then the thud of the shed door. The rattle of a bicycle being pulled from the tangle. And Sofia, or Sonya or Silvia down there, unravelling the lock from her bike, standing in a moment to wheel it down the path towards the gate. In a few moments she could be standing right here, in this room. Standing above him, looking down. At him curled like a dog around the toilet, bollix hanging out of his dirty pyjamas. Drooling gob twisted off to the side. One weeping eye.

He opens his mouth, then closes it. It seems uneven, the lips not quite meeting. He goes to open it again then changes his mind. For some reason the dry-cleaned suit comes into his head. He searches for the colour, the texture of cloth. The pinstripe navy? The charcoal grey? Or was it the black – funeral black?

The Suit

14 January 2010

EVERY DAY HAS ITS purpose; a structure on which to pin up his hours. Thursday – the pension; Wednesday – his visit to Jack. On Tuesday he feeds Mrs Waugh’s cat while she visits her sister in Skerries. Friday he goes into Thomas Street; buys his few messages, has his weekly ration of pints. And Saturday; Saturday is his day for the garden. Sunday and Monday are a bit loose for his liking. At least, whenever he’s looked back on a time to regret, it always seems to have fallen on one of those days. Boredom, he supposes. Other factors too that he doesn’t care to put a name on. Before he so much as opens his eyes he rummages for the day and the date. Then he draws up a map of the hours in his head. It’s a habit left over from his working days – scheduling was what Slowey used to call it – the ticking off of a list, the margin at the side for the where, what and when of it all. But he knows there’s a touch of his mother there too, preferring one thing to belong to one specific day, from Monday a stew day, to Sunday a roast; week in week out, month after month, all the years of her housewifey life.

Today is unique; a day of preparation. He’ll be run off his feet. For a start the clothes brush will have to be located, ditto his black overcoat. And in case he decides to go up to the altar, he’ll have to check on the soles of his black leather shoes. The two white shirts he left steeping last night will need to be rinsed out and hung up to dry – one for the removal tomorrow evening, the other for the Mass the following morning. That’s the thing about funerals, they derail the whole week, giving rise to an entirely different batch of errands; a Mass card, the clothes brush, the shoes, and flowers – he’d better see about getting a few flowers. A wreath or maybe one of those oval-shaped jobs? He’d leave it to the girl in the shop to decide.

Farley stands in the hall, the suit rolled into a bag at his feet, his fists inserted into his good black shoes, turned upside down for inspection. The first safe day after snow. Nothing in the house but cornflakes and butter. He’d better get a few messages while he’s at it. A list; maybe he should have considered making a list. He studies the shoes. Just as he thought – a hole in the right foot, the shape of an eye. The left one is perfect. Would he get away with just bringing the one shoe in to be soled, or would that seem like he was just trying to save a few bob? Should he bring both in then, just to prove he’s not? He weighs the shoes, stepping them up and down on the air. But what sort of a fool would only get one shoe soled anyway unless only one shoe needed it? He tilts the shoes now to see what they’d look like on feet attached to legs in the kneeling position. The eye still glaring out. He feels a bit agitated, sort of itchy all over, but on the inside of his skin where it can’t be scratched. And the light of snow is making his eyes a bit wonky. A short flare of anger warms up his chest. So what if they think he’s a skinflint? They either want his business or not. And come to think of it – why is he even considering going up to the altar in the first place? It’s not as if he’s believed in that fucking eejit for more than forty years.

Farley pulls in a long breath and looks at himself in the mirror. Even under his good tweed hat and over the knot of his maroon cashmere scarf, his face has a greyish hue. A small round stain of resentment on each cheek. Cabin fever. Cabin fever on top of a bad’s night sleep plus a lack of nourishment. That’s all that’s wrong with him. Nothing a bit of air, a decent bit of grub wouldn’t sort out. He plonks the right shoe into the bag on top of the suit and drops the left shoe onto the floor. And as for going up to the altar? Why wouldn’t he go, if he feels like it? What or who’s stopping him? It’s not a question of believing anyhow, it’s a question of belonging. He gives himself a nod in the mirror and repeats the phrase in his head. A question of belonging. Then he tucks the bag under his arm and releases the first chain on the door.

He notices the bag comes from Clery’s then and can’t imagine why, because to the best of his memory, he hasn’t been there these years. A woman was with him last time – maybe as far back as his first suit for work. In which case it wasn’t a woman as such; it was his mother.

The phone catches his eye, sitting up there on its crescent-shaped table. He reminds himself that in the past twenty minutes, he’s checked it twice already for messages. Once after he’d been upstairs having a shave, in case, just in case. And again when he’d come back in from doing the rounds of his snow-injured garden. No point in checking again. He sets to work on the door bolts, shoving and grinding until, reluctant as old bones, they eventually give and he draws them back; one, two and three. Then, as if to catch himself off guard, he skips back to the table and snatches the receiver from the phone. The earpiece cold on his ear. He listens for the broken signal that means a message is waiting. But all he can hear is the relentless eeeehhhhhhh jeering down into his earhole. He replaces the receiver and pulls on his gloves. You’d think one of them, even one of them, would have bothered their arses to pick up a phone.

Outside the cold air grabs a hold of his face. His hand, clumsy in its glove, stays on the doorknob. Maybe they left him a note? He toes the corner of the doormat back – nothing but a light skim of ice. Then he checks the letter box from the outside in, in case – alright, a very small note – had somehow got jammed there. But all he can see is a clear view of the hall he’s just left, the curly iron legs on the hall table, the shoe on the floor, the smug, silent phone. The mirror.

A dark blue car comes around the corner, a quiff of old snow on its roof. An Audi it looks like, a good car in anyway; something one of the Sloweys would drive. Farley feels his heart reach out to it. That could be one of them now, come to break the news to him in person. The car slips by, a stranger’s face at the wheel. No. No, of course not. He’d had to hear it from Mrs Waugh last night. And she’d only phoned because the cat had gone missing: ‘I can’t stop thinking the worst,’ she had said. ‘I mean, every time I open the back door, I keep expecting to find him frozen stiff on the step, like that poor man in Wexford found at his own back door – imagine.’

He hadn’t liked to point out that it was hardly the same thing; a man, a cat. And that anyway a cat would be far more likely to survive with its pelt of fur and its natural slyness, than some poor snow-bewildered fool who’d probably just locked himself out of his house by mistake.

‘Ah, he’ll be back, Mrs Waugh,’ he’d said, ‘don’t you worry, he’s just gone off on a ramble, cats are like that, you know.’

‘He’s been neutered,’ she’d sniffed, like he’d been trying to insult the cat’s character. And then just as she’d been about to ring off, like an afterthought she could just as easily have forgotten: ‘Ah, comere you’ll never guess who’s after dyin!?’

The way she had said it. Detached but affectionate – the way people are when an old actor or television personality pops off. A distant death anyhow. For some reason Bruce Forsyth had come dancing into his head.

‘Who would that be, Mrs Waugh?’ he had asked, wondering how much longer he was going to have to stand freezing his balls off in the hall.

‘Ah, you know, your man, what’s his name? Always drove the big car – even when no one else had a car. Ah God, what’s this his name was?’

An alarm went off in his head – the car.

Mrs Waugh cackled, ‘Ah, what am I talkin about – sure you probably know all about this already – didn’t you used work for him?’

Silence. He couldn’t think of the smallest word to break out of his silence. He was sure she would notice and wonder.

‘Slowey!’ she squealed, all delighted with herself for remembering. ‘That’s right, Mister Slowey. Of course, I didn’t know him meself, just to see, like in passing, he might give a wave out the car and that. Fine-looking man but. They had the house with all the extensions on it – that’s right. A few kids – hadn’t they? Two boys and a girl? No, three boys. One of the boys emigrated – am I right? ’

‘Yes,’ he’d said. ‘No, yes. I mean, no.’

‘How old would he have been – in his seventies anyway, I suppose – was he?’

‘Seventy-seven last week.’

‘Go away! Well, he didn’t look that now. Not a bit. Harriet got the impression the removal was Friday, which struck me as a bit funny because you’d think it’d be tomorrow. Like if he died this morning? The snow maybe, delayed matters.’

‘Harriet…?’

‘Ah, you know Harriet?’

‘O, of course,’ he had lied, just to avoid a big long explanation of whoever Harriet and all belonging to her might be.

‘She heard it in Centra. Anyway. There you go! Another one gone! Which one of us will be next, I ask! So listen – won’tin you not forget now to give us a ring if Shifty turns up?’

‘Who?’

‘Shifty, the cat. If he turns up. And meanwhile if he comes home I’ll be sure to let you know straight away.’

‘O, please do,’ he’d said, as if he gave a fuck about her or her stupid cat.

Farley looks into the snowy estate and slowly lets go of the front door knob – there will be nothing to hold onto for the ten steps or so that it will take to get him from here to the gate. He looks up at the sky, a fragile blue curve above the dark houses that puts him in mind of a china bowl from a long-ago sideboard; his mother’s or maybe his grandmother’s. Then he pulls his hand through the loop of the bag, settling it in at his elbow. Martina hadn’t thought much of Clery’s – a dear hole, was what she always called it.

He won’t fall, he won’t fall. He imagines what he must look like now, dithering along the garden path like a half-pissed tightrope walker, testing each step as he goes. He wonders should he keep his foot light, in case he needs to regain his balance, or should he put the weight down on it, to secure his position? He thinks of the two boy scouts who called to the door during the last big snow in the eighties and tries to remember what’s this they’d said was the trick to keeping the balance? Something about turning the toes of one foot inwards or was that outwards? A picture comes into his head then; an upright skier padding along in the snow. He turns in his right foot and proceeds.

At the gate Farley pauses, holding on to it for a moment while he peers up and down the endless road. A mile and a half long – someone once told him. He sees others who have ventured out, moving at intervals, gingerly along, keeping close to the railings. Even the younger ones seem a bit wary, although most of the snow has skulked off during the night. Only a few grey humps remain, along the shaded side of the road, caught against a wall or tucked into a kerb, like mounds of dirty underwear waiting to be brought to the laundry.

You’d think they would have sent someone. A grandchild, a neighbour, a lackey even. Or had the Sloweys run out of lackeys by now?

He moves off. Gaining a bit more confidence as he goes, he loosens his stride and firms up his footfall. The lukewarmness of a fizzy sun on his face. No boy scouts this time to see how the old folk are faring. Conroy would have said that’s on account of all the child molesters that’s going these days. Kiddie fiddlers, Conroy used call them; a term Farley always found a bit hard to stomach. Years ago they’d say a child was interfered with. But then again, that’s probably not strong enough either. He straightens his toe, his two feet realign – he won’t fall, he won’t fall.

His eye grazes ahead, pausing on houses where he knows old people live on their own. People he might never have even spoken to, beyond an occasional nod or a ‘not a bad day after’ in passing. But he watches out for them just the same, the way he knows they watch out for him. Older people are like that, he reckons. A combination of concern and competitiveness. Who gets through a cold spell, who perishes. Who’s been unlucky, who’s been a fool. It keeps them going. That touch of glee in Mrs Waugh’s voice last night when she broke the news about Frank, for example. Or the way you’d see some fellas in the pub hop on the obituaries in the paper before they’d so much as read another word. Often it would be the fellas in the worst shape who’d be keenest to read, like they were half-expecting to find their own names in there. There was a time you could rely on the house itself to keep you informed. A wisp of smoke from the chimney; a bottle of milk not lifted from the doorstep. Now bar banging down a door and sticking your nose right in, it’s near impossible to guess who’s in and who’s out. Who’s lying on their own at the bottom of the stairs. Who’s turning into a human iceberg right outside their own back door.

He leaves the estate for the main road where he waits at the kerb for a pause in the traffic. Farley knows he could stand here all day waiting like Moses for the Red Sea to cut him a passage. Or he could walk on down the road to the pedestrian crossing maybe fifty yards or so away. But he feels tired, a bit weak even, and fifty yards just seems way too far. All the sudden fresh air, he supposes. One tingling cheek, like a dentist’s anaesthetic beginning to wane. He’s as happy to have the traffic as an excuse to stay put. His eye relaxes into the blur of moving cars, his ear is lulled by the dull arrhythmia of passing sounds. He thinks about snow; man’s strange relationship with it, almost romantic. The way it lures you into a false sense of serenity with its beauty and silence, and yet would do you, given half the chance.

A few days ago, enchanted as a child, he had stood at the window, watching its dainty arrival. Twilight, and as the light had diminished, the snow had gained momentum. And a sort of yearning had come over him that it would stick to the ground, stay and expand until all the houses and gardens in the estate were swollen with snow. It had grown dark, but he hadn’t turned on the light. He wanted to stay gawking out, without the neighbours seeing him. Even though all over the estate, grinning like simpletons out from dark houses, there were probably others just like him; Mr Kerins around the corner, Mrs Waugh in the house backing onto his; the youngone next door. By morning it had already started to turn vicious, devouring his garden, killing his little plants, freezing the blood in his body. Laying siege to him too, making him afraid, making him worry. About food and fuel and the fact that he’d no candles if the electricity went. About the fact that boy scouts don’t call any more. Nobody did, nobody would. Not even the girl next door. And yet for all that? He had stood out in the back garden mourning all that had perished, while at the same time he’d been filled with an inexplicable belief in life, feeding the birds with bits of fruit pulled out of the back of the fridge – stupid fuckin tears in his eyes! He had said out loud, ‘I don’t want to leave this; I don’t want this to be my last snow.’ Wherever that morbid thought had come from! Of course, he hadn’t known about your man in Wexford at that stage or he probably wouldn’t have chanced going out in the first place. Garden or no garden. Birds or not. Elderly, the news had said the man was. Sixty-five years old? Since when did sixty-five become elderly?

Behind him a bus screeches and stops. From the corner of his eye the shapes of passengers alighting, tiny and blurred, spilling out of his eyes like tears. He blinks and his vision almost settles. Two youngones, school bags to bosoms, step up beside him, faces turned to the traffic, knees slightly bent as if waiting to jump into the turn of a skipping rope. He decides to take the lead from their young eyesight, placing one foot off the kerb onto the road. But the youngones are too quick for him, and are across the road before he can think, in the careless half-run, half-walk of limbs that don’t have to worry about falling. Two men come up behind him, yoddling to each other in foreign voices. Farley wonders if maybe they’re his neighbours, the housemates of the little gnome next door. They step around and stand right in front of him as if he just isn’t there. Big brawny lumps smelling of baby talc. They don’t even break their stride as they cross over, in fact one car has to slow down to facilitate them. Finally, there’s a father holding his daughter’s hand, patiently listening with a tilted ear. The child breathless to report every inch of her story which they take between them across the wide busy road. Leaving Farley alone.

He looks up the road. Traffic herding over a crest in the distance. There’s definitely something the matter with his eyes. The cold maybe? Because it feels like he’s looking through a skin of ice. Shapes tumbling into one another, breaking into pieces, then re-forming again. He closes his eyes and shakes his head. When he opens them again, one side of his vision is completely blotted out. A speck of dirt maybe. He pulls his right eyelid to one side, stretching it out, until bit by bit the darkness disperses. He steps back up onto the kerb and passes over the grass verge towards the pavement that leads to the pedestrian crossing fifty yards or so down the road. Yet another thing he knows he will never do again – is stand at that particular section of the kerb, taking his chances, cheating the traffic. He walks slowly under the lean winter trees.