Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

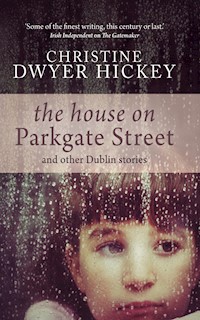

A child wandering alone through a racecourse; an elderly lady grasping at a thread of memory; a young girl watching prostitutes from her window as they ply their trade; an Indian taxi driver living in his cab: these are some of the fractured lives and fragile hearts we meet in The House on Parkgate Street and Other Dublin Stories. Set in various eras, at various times of life, each story is a unique and perfectly carved gem embedded in the city of Dublin. With her customary wit and empathy, Christine Dwyer Hickey brings us an intimate portrayal of the city and some of its people in these beautifully observed stories, collected here for the first time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 267

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The House on Parkgate Street

THE HOUSE ON PARKGATE STREET

First published 2013

by New Island

2 Brookside

Dundrum Road

Dublin 14

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Christine Dwyer Hickey, 2013

The author has asserted her moral rights.

P/B ISBN 978-1-84840-290-4

ePub ISBN 978-1-84840-291-1

mobi ISBN 978-1-84840-292-8

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island received financial assistance from

The Arts Council (An Comhairle Ealaíon), Dublin, Ireland

IN MEMORY OF BILL

Contents

Across the Excellent Grass

Absence

La Straniera

Saint Stephenses Day

Esther’s House

Windows of Eyes

Bridie’s Wedding

Teatro La Fenice

The House on Parkgate Street

The Yellow Handbag

Across the Excellent Grass

For a while she believed the racecourse was in a different country, so strange it seemed from her own house, just twenty minutes ago. Each suburb passed was a city crossed, each mile a thousand covered. It was as if she’d been on a day out with Mary Poppins and had placed a button-booted foot down on a chalk-drawn scene, watching it melt into the pavement as the picture grew to life about her, making her part of a mystery that was not her own.

And this is how small she was then and always walking with the left arm raised and the left hand held by a power greater than hers, that guided and pulled and shrugged her through the crowds, and coming face to face with nothing except for handbags square and smooth or binoculars, badges bunched swing-swong from their straps. Flutter – ‘I have been here’. Flutter – ‘I have been there’. And no one to see their gold-cut letters save the child that tagged behind.

And then her head would be skimmed by a dealer’s stall, fruit upon fruit laid out on sun-sharpened cobbles. And it could have been the roof of a Catalan house. And it could have been a Spanish voice that cried in words harsh and almost familiar, ‘AAAPPLEANORRINGE. OOORINGEANAPPILL …’

And then the arm could come down and wrap itself around her and she would be raised legs loose little stork, eyes squealing at the two bubbled toes of freshly whitened sandals. Flying yet higher for a moment in a soar so glorious. Then swing. And then swoop. And how would they land? Please not on the bars of the iron-cruel turnstile or not so the dust rises over their straps. Veer to the concrete clean and hard and the spark that shoots up through the legs won’t matter. Just keep the white white, little stork. Keep the white white.

And then the loud grunt beside her head.

‘She’s getting big, eh? She’s getting big.’

‘I’ll have to be paying for her soon enough.’

Sometimes the crowd, so sure before, would hesitate and stop and the drum of hooves would come from behind the trees, passing in a string so fast they might be caught in a photograph, so fast no individual movement could be seen.

‘Quick. What was the first number you saw?’

And, quick, she would lisp the first number that came into her head, never really able to pick out any one in the streak of saddle and flesh and the long, bright blur of colour mixed.

‘What did she say? What did the child say?’

And for once she could be heard and welcome, face puffed pink from her own importance.

‘Ah yes. The luck of the child. Number 3, did she say?’

‘What’s that in the next …? Ah yes. The child brings him luck.’

But he keeps a little black man in the boot of the car for that. Not a full body, just a head and a neck. He said he lost his legs at the Curragh and his hips at Fairyhouse and his arms and his chest at Cheltenham and he could have lost his willy anywhere. Longchamps, maybe Ascot. And once a man sitting in the front of the car had said, ‘He wouldn’t be the first fella to lose his willy at one of those places.’

Now all the luck was in his head and his brains were in his neck. She said he must have been very small anyway even when he had all his bits and bobs. ‘Ah, but you see,’ the man in front had said, ‘his mother was a pygmy and his father was a jockey and so it was bound to be.’

And now the head as small as a fist came everywhere, an eye on either side and cut like a tadpole and being able to see east and west at the same time. Able to see you no matter which side of the car you were on. And scratches on the pointed chin and across the mushroom nose where the luck had chipped off over the years, and she must chip off even more, graze her hands raw if need be, so important it was to the day. Feeling his hard head on her palm when, after her father, she would rub her hands in rotation, roundy round, and copy the chant that extracted the luck. But she was afraid of him: the little black man that was in charge of the luck. For yet she might see her father’s elbows sharp above her move like scissors in the air, and yet she might see fall to her feet the slow, coloured confetti of torn-up dockets drop disappointment on their day.

And she would think of him now, his mean black head stuck in the hole of the spare tyre where she had left him, upside down. How angry he would be. How spiteful, if he chose.

But the horses are past now and the men in grocers’ coats flip back on either side leaving a gap for the feet to move through. The crowd begins to spread itself apart leaving spaces where she can see now, the familiar and the wonderful. Here on the right, and penned in by shiny white fence, the ring of careful grass and its outer ring of clay scuffed like brown meringue, where delicate hooves have tipped themselves upward on parade. And here, too, another brim with stool after tiny red stool, the exact amount of space from each to each, and the spongy seat tight clung with artificial leather. But not hers now. Not yet. Now a bottom droops over each one. Later on, when the spots and flowers and the salad and whirls of female colour have taken themselves off, and later on when the men in straw or donkey-brown hats have led the way to celebration or condolences. Then. Then they would be hers, to spin like tops or talk to as a teacher to her pupils. And she can watch them from the seat that travels around the tree amongst the green and the quiet and the dots of dockets, thin as tissue and as useless now. She might eat a bar of chocolate while she waits, square by square and slowly, like the mouth on the television. Or the other one, the one that runs in pyramids down a pale yellow tunnel of paper and foil, the points of chocolate catching on the roof of her mouth at first, then melting into almonds and honey and secret crunchings. So long, it may take all year to eat it. So long.

But that would be later and now is now and her father’s thick, warm hand is ever pulling.

First walk up to the little house in the middle that looks like a wooden tent, the one whose floorboards moan beneath the feet, and the woman with the white fluffy hair and the chalky lips, penicillin pink. And waiting. Always waiting for the talk to stop.

Up in the air and only some words heard, ‘claiming this and carrying that and ground too this and proved form here and no chance there and Barney Chickle in the long bar says sure fire certainty from the brother’s yard and sure fire certainty to lose if that eejit’s and …’

Oh, hurry up. Hurry … and she grabs the cloth of his trousers making ding-dong bells from the baggy bits behind his knee.

Turns on his heels and nearly knocks her.

‘Got to go.’

‘Good luck.’

‘Yeah. Good luck.’

Now at last outside and there they are. Up above and skirting the balcony, cloaks red and navy hanging across shoulders and more navy in the hats neat as bricks on top of their heads and raising instruments like golden toys from the raw knees squeezed up from woolly socks to pursed lips that push and pull sound into shape for the crowd below. And making a change to the mood too, and the step. The men a little looser at the knee, the women a little heavier at the hip. And hooop – a flash of brass stands up and caws and here and there a human hums in recognition. These are the Bold Boys. The boys from Artane. The boys who look no one in the eye unless he too wears a cloak and an instrument. The boys who will come down the wooden steps and march red-necked and eyes down before the off, to point their brass to the sky and herald den den derrran … the horses are coming, they are coming … here they are.

Oh, what did they do that was so bold? No one tells. Is it as bold as her bold? Is it as great? Could she end in a place where sins are hidden under the fall of a cloak. Could she play music so sweet?

And now turn to the clock standing like a giant’s watch with hands so long and spear-tipped pointing at lines. No numbers. Behind it the bushy tails of the Garden Bar peep green through the fence. Women move and stop. Move and stop. Eyeless under brims so wide. Except for lips – pink and orange and red, one rosebud on each plate.

And more knees to greet and more possibilities to be swapped and sometimes stop and, ‘My, she’s getting big,’ and, ‘That can’t be her – I wouldn’t know her, soooo big.’ And a child could be a giant before the day is done and a child could wear the watch that is a clock with lines. No numbers. But the child smiles tiny through one eye and dips the other scraping off the trousered leg she knows.

‘And do you want to go wee-wee, love?’ Mini’s rosebud asks, and lowers down a hand with fingers knotted and striped with gold, stretching out nails that have been dipped in blood.

And no one looking down to see her shake her head. No wee-wees.

‘Take her, Min, as sure as J she’ll want to go in the middle of the race.’

So unfair, big fat lie, she never would. She never did. She can go by herself. Big girl.

‘See you in the Weigh-Inn so.’

‘Thanks, Min, thanks.’

Then he turns away to Mini’s husband, little man, leprechaun face. Used to ride himself before – now he talks his way over every furlong to the post, she heard a woman’s voice say.

Min never says a word when they’re alone. Just pulls. The trinkets at her wrist tinkle softly. A fruit basket, a star, a moon, two little balls on a chain. Always talks and buys her crippsanorange, crippsanorange, when daddy’s there.

Only one woman in the ladies’ room looks different. Only one of so many. She wears a dress like a pillowslip with a zip up the front and her hair like a woolly hat pulled down around her ears. She is always busy opening doors and handing out pins, eyes looking slyly through the mirror at big brown pennies drop, drop, dropping into the ashtray.

They line up by the sinks and all their twins line up in the mirrors and all the while pencils and puffs and brushes touching this and that on upturned faces. And silence. Mostly silence. There is nothing to hear but toilets clear their phlegmy throats and tick-tack heels move and stop. Move and stop. And, ‘Thank you, Ma’am, thank you,’ as the pennies drop.

She hates the smell. The pushy perfume smell, heavy on the air. It makes her want to vomit. She is afraid she’ll be too sick for her chocolate. Her eyes sting because of the smell or because she wants to cry. Why? She doesn’t know the why.

Mini comes out plucking at her skirt. There is blood on her heels. Min asks the woman for a plaster. She takes out a foot that is big and mushy, blood between heel creases, tough and brown. She spreads the Band-Aid onto the wound. Min doesn’t say thank you. Nor does she wash her hands. She puts on more lipstick though and then they leave. Min doesn’t notice that she hasn’t done her wees.

They walk into garden of the gnomes. Her father sits amongst the furrowed faces of the little men. But they all stand, feet firm and legs in archways like plastic cowboys.

There is no laughter now. Just talk. From earnest mouths that still manage to hang a tipless cigarette from one corner, making it dance with words. Everyone owns dark-brown bottles. Some held, some tilted, some left standing for the light to shine through. Her father points his upside down into a glass. He makes black porter crawl up and leave a tide. Through his lips he sucks the black. Ahhhh, and the tide falls down to the bottom of the glass then clings. The little men have funny names. Nipper and Toddy and one called The Pig. The Pig runs messages for her father. Slow winks and wise nods. They pass rolls of money and whisper. He laughs when her father laughs.

This place makes her think of the city at night when it should be dark but is not. The balls of light hang from the ceiling like streetlamps and the crowds shove at each other, unafraid. Her father stands up. He is as tall as the highest shopfront.

‘I’ll go up so and take a look at this one.’

He fingers through his pocket and takes out a note. He points it at The Pig. ‘Get a drink for the lads,’ he says. When she looks back she sees The Pig nodding at each one and asking what he’ll have, as if the money were his own.

And now up the stairs. She pulls herself by the wooden banisters hand over hand. She must stretch her knees up to her shoulder so as not to delay. The man with the loudest voice calls out across the course. Somewhere outside she can hear the Bold Boys denden derren the start. She can see nothing. Only if she droops her head to where feet stand with feet, down step after step. Or if she leans right back and looks up to the inside-out roof that lets in no sky. She is too small, a flower in this forest.

The man with the loudest voice draws one long word out across the course. It is a word with a thousand syllables, screechy and pulled through his nose. The crowd begin to join him muffling out names of place and colour and unlikely title.

She lifts back her head to look for the bird. She knows he is here somewhere, huge and still, his head turned in profile, his wings spanned over painted flames that rise like feathers from his feet. Then she remembers. He is on the other side of the roof, the bit that slopes like a wooden fringe, where he can see the fences bend and the horses roll along the grass.

The woman on the step below her wears bright-red shoes with heels as long as scarlet pencils. She begins to bounce now, her dress flouncing slightly and her feet clicking up and down again. She stops for a moment. She starts again. This time she lifts one foot altogether from the ground. There are scratches on the sole of her shoes and a name in gold that is beginning to fade. Letters from her own name. She shuffles to the edge of the step to take a closer look. The foot starts to come back to the ground, heel first. This time it doesn’t return to its own step. This time it pauses in the air and then falls, landing on the step above where her white sandals perch waiting on the edge.

It is like a sword flung from a height onto her toes. She calls out but her voice is silent amongst the urging and the pleading amongst the …

‘Go on, ye good thing. Go on.’

She cannot reach for her leg because her foot is trapped beneath the sword. She is pinned to the step by the point of it, stabbed between her big toe and the next toe. She is afraid to move in case the sword slips and cuts off one of her toes. The tears pop out by themselves and roll like rain down a windscreen. A pain pushes down from her stomach and she screams. She knows what is about to happen now. The woman moves her heel away and her foot is free. But it is too late. She lowers her head. She watches the water trickle down the inside of her legs, down, down it goes, staining the hem of her upturned socks. She opens her legs and lets the rest fall down in little splashes, darkening the concrete with its pool.

The roar of the crowd cuts to silence; the last dribble drops. People begin to turn round towards her and start up the steps to the bar at the back. The woman in the red shoes looks at her, then at the pool, then back at her. Her rosebud tightens in disgust.

*

Afterwards she clutches her chocolate like a staff and walks through the crowd to the green outside. She can hear her father laugh loudly behind her. She can hear him change his voice to say, ‘Stay on your tree-seat, I’ll be out in ten minutes. Good girl.’

She walks on feet she must keep soft and sneaky, laying one before the other as though it were a game. She is unheeded by the stragglers and the dealers. She keeps her head down, watching the frozen splashes on her sandals and the dent so deep that it is almost a hole. Her thighs smack kisses off each other, rubbing the rash that is beginning to rise. Between them she feels her knickers dry hard and crisp, like knives cut into butter.

And in her little head, just for a while, she forgets her name and this place through which she walks. Though somewhere before her she knows there’s a little black man waiting to be unstuck. And behind her the Bold Boys are folding instruments silver and gold into themselves and watching her from a height wade slowly away from the wooden house, across the excellent grass.

Absence

The first thing he notices is the silence. He’s in the back of a cab, a few minutes out of Dublin airport, on a motorway he doesn’t recall; cars to the left and right of him, drivers stiff as dummies inside. And he thinks of the Mumbai expressway: day after day, people hanging out of windows, exchanging complaints or pleading with the sky. The outrage of honking horns. And the way, for all the complaining and head-cracking noise, there is a sense of something being celebrated.

Frank had known not to expect an Indian highway – youngfellas piled on motorbikes and leathery-faced old men wobbling along with the luggage on top of buses – but what he hadn’t expected was this. This emptiness.

He has the feeling they may be going in the wrong direction and, when a sign comes up for Ballymun, wonders if the driver could have misheard him. Frank thinks about asking but doesn’t want to be the one to break their silence. At the airport there had been a moment, while lifting the luggage in, when a word might have been enough to start up a conversation. But a look had passed between them for a few tired seconds, and somewhere inside that look they’d agreed to leave each other alone.

He’d been expecting the descent through Drumcondra anyhow. Had it all in his head how it would be. The escort of trees on both sides, the black spill of shadow on the road between. There would be the ribbed underbelly of the railway bridge and then, where the light took a sudden lift, a farrago of shop and pub signs running down into Dorset Street. He’d been half looking forward to playing a game of spot-the-changes with himself.

A memory comes into his head then: a day from his childhood, upstairs on the bus with Ma. They were on the way to the airport, not flying anywhere of course, just one of those outings she used to devise as a way to keep them ‘off the road’ during school holidays. They’d spend the day out there, hanging around, gawking. At the slant of planes through the big observation-lounge windows. Or the destination board blinking out names of places that vaguely recalled half-heeded geography lessons. Or outside the café drooling over the menu where one day, when Susan had demanded to know why they couldn’t just go in, Miriam had primly explained, ‘Because it’s only for the fancy people.’

Miriam loved the fancy people – passengers with hair-dos and matching clothes. Johnny had no time for them. too showy off, he said, flapping their airline tickets all over the place like they thought they were it. And because Johnny had felt that way, Susan and Frank had too. In any case, they preferred to look at the pilots and air hostesses who really were it: striding through the terminal, mysterious bags slung over their shoulders, urgent matters on their minds. Not a hair out of place, as Ma always felt the need to say.

Upstairs on the bus – three kids kneeling up at the long back window. Ma sitting on the small seat behind. In the reflection of the glass her head sort of see-through like a ghost’s. He’d kept turning around to check she was still there, with a solid head and real brown hair on top of it. Her hands were in their usual position – right one for smoking, left one for her kids: to stop a fall or wipe a nose or give a slap, depending. He’d been holding onto the picnic, the handles of two plastic bags double-looped around his wrist. Minding it and making a big deal out of minding it too, because the last time when Susan had been in charge she’d left the bag at the bus stop. A low throb in his wrist, he’d the handles wound that tight, and the farty smell of egg sandwiches along with the fumes of the bus making him feel a bit sick.

In the memory he doesn’t see Susan, and this bothers him now as it bothered him then. That was the thing about his big sister: it was a relief when she wasn’t with them, riling Ma up and agitating the atmosphere with her general carry-on. Yet when she wasn’t there, he always felt the lack of her. She was being punished, most likely, left behind with one of the tougher aunties or locked into the box room for the day. Punished by exclusion. Because as Ma would often say, ‘Slapping Susan was a complete waste of time.’ Not that it ever stopped her.

And that’s it – the memory. No beginning, no end, meaning little or nothing. Yet it still manages to catch him by the throat.

Frank leans forward, ‘Actually, that was Ballyfermot I wanted, not Ballymun,’ he says.

‘Yeah, I know,’ the taxi man grunts.

The first Dublin accent he’s heard, apart from his own, in nearly twenty years – and that’s about all he’s getting of it.

*

The road sign for Ballyfermot gives him a start, like spotting the name of someone he once knew well in a newspaper headline. A few minutes later they are passing through the suburb of Palmerstown and Frank is struck by the overall beigeness: houses, walls, people, their faces.

At Cherry Orchard Hospital, the traffic tapers to a crawl. The hospital to the right, solid and bleak as ever and, still firmly in place, the laundry chimney that had been his view and constant companion during his three months there when he was a kid. He can feel Da now. Trying to get inside his head, shoulder up against it, pushing.

They draw up alongside the hospital gate, walls curving into the entrance, and it comes back to Frank, the lurch of the ambulance that night, the pause and stutter of the siren as if it had forgotten the words to its song. And him coming out of his delirium just long enough to see snowflakes turning against the black glass of the ambulance window and wondering how come he was sweating so much when outside it was cold enough for snow. He had asked where they were, and when the ambulance man said Cherry Orchard he’d thought it the loveliest name he’d ever heard.

The taxi man tuts at the traffic then switches on the radio. A voice comes out talking about money. Another voice over a phone line, shaking with nerves or possibly rage. The taxi man reaches out and switches the silence back on.

Frank remembers now the sound of the ambulance doors whacking back and the sensation of being hoisted up and lifted into the darkness and the cooling air. And looking up into the muddle of snow, he had got it into his head it was cherry blossom falling down on him.

He must have been ranting about it all during the illness anyhow, because after he got better Da bought him a book of the Chekov play. He was a fourteen-year-old youngfella who fancied himself as a bit of a brain, mainly because that’s what everyone kept telling him. Yet he couldn’t get beyond the first few pages of, what seemed to him, a boring old story about moany-arsed people with oddly spelt names. He’d kept turning back to Da’s inscription – To Francis, my namesake, who, unlike the author, got out alive. With fondness, Frank Senior – and trying to understand at the time what the hell did it mean or why – why would his da write to him like that? Like he was a grown up, like they were strangers?

The taxi begins to move again; the cars break away from each other and Ballyfermot comes into view. Frank looks out the window. As far as he can see, nothing much has changed, apart from one modern-looking lump of a building further down the road. It looks like the same old, bland old Ballyer that it always was. Rows of concrete-grey shops under a dirty-dishcloth sky. Even the weather is utterly familiar: stagnant and damp. The threat of rain that might or might not bother to fall.

He can’t remember the address. Not the name of the road, not even the number of the door – it just seems to have fallen out of his head.

He can remember everything else though: that the road is long and formed into a loop, and that the house is on the far end of the loop, and that the turn for the road is coming up soon. He begins to feel queasy; in his gut, the Aer Lingus breakfast shifts. And he wonders again, as he wondered while eating it, what had possessed him to order it because it certainly hadn’t been hunger. Nostalgia then? For what? Sunday mornings, bunched up together in the little kitchen, steam running down the walls? Or Saturday nights when Ma and Da would come rolling home from the pub? Ma slapping rashers onto the pan. Da voicing the opinions he hadn’t had the nerve to express in the pub, hammering them out on the Formica table. Ma agreeing with each revision, laughing at just the right moment. The waft crawling upstairs into Frank’s half-sleep: black pudding, burnt rashers. Shite talk.

He presses his fingertips into his forehead, rotating the loose flesh against the bone of his skull. The skin on his face feels greasy and thick for the want of a shave, and even though his nose is stuffed from the flight, he can tell he doesn’t smell the sweetest. He should really go to the house first, clean himself up a bit. A quick shave, a change of shirt. But he isn’t ready for the family, the neighbours – all that.

‘What time is it there?’ Frank asks the driver, whose finger even manages to look sardonic when it points to the clock on the dashboard. Frank looks down at his own watch, sees that it agrees.

Three minutes to eleven. All he has to do is say, ‘If you wouldn’t mind taking the next right – just up along here.’

He holds the sentence in his head for a moment. But the car skims past the turn and the moment has gone.

The taxi man speaks, startling Frank with the sudden rasp of his voice.

‘Where to?’

‘Oh. Let’s see, you know the church just up the road there? If you could just –’

‘Right.’

‘Actually, maybe if you could, you know, pull in around the corner down the road a bit and –’

‘Right.’

‘Or –’

He sees the eyebrows go up in the rear-view mirror.

‘No, that’ll be fine. Down that road there, near the school, grand, that’s grand.’

The car takes the broad corner, passing the slate-grey church. Frank looks down at his feet.

The shock of the taxi fare: he feels like saying, Christ you could travel from one end of India to the other for that. He hands over a note and says nothing. The taxi man picks up a pouch and begins pecking at coins. He opens it wider and peers down into it. ‘You home for good or a holiday?’ he mutters as if he’s talking to some little creature in the bottom of it.

‘A fortnight,’ Franks says, holding out his hand for the change.

‘Listen – I do the the airport run, so when you’re headin’ back give us a shout – right? I’m only down the road. And I’ll do you a good deal,’ he pokes a business card at Frank, ‘off the meter, like.’

‘Oh, thanks,’ Frank says, ‘that’s good of you.’

The taxi man shrugs. ‘Yeah, well, business is crap is all.’

Frank slips the card into his pocket.

He pushes the haversack back into the seat, opens the front zip and edges his hand in. The haversack is bloated, the space tight. He can feel the taxi man watch as he rummages around. He pulls out a black tie, bit by bit, holding it up for a moment like a dead eel between his fingers. Through the mirror their eyes meet. The taxi man nods. Frank nods back.