7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

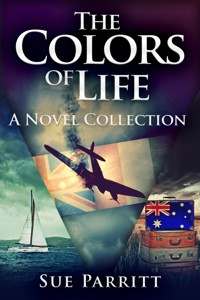

A collection of three novels by Sue Parritt, now available in one volume!

A Question Of Country: In 1969, newlyweds Anna and Joseph Fletcher receive a life-changing letter from Australia House. Their idealistic dreams lead them to fall in love with their adopted land, but tragedy strikes just months later. As time passes, Anna finds solace in a fictional world she has crafted. However, when a new challenge emerges, she must decide whether to confront it with courage or retreat into her fantasy realm. Will she dare to face reality or remain in the safety of her imagination?

Feed Thy Enemy: In this heartwarming tale based on a true story, a British airman's act of kindness during World War II resonates decades later. As middle-aged Rob embarks on a holiday in Italy, he grapples with the ghosts of war and his own inner battles. Flashbacks to his heroic attempts to help a starving family evoke suppressed memories of love and sacrifice. With PTSD and depression weighing on him, Rob must find the strength to confront his present challenges. Sue Parritt's Feed Thy Enemy is a poignant and inspiring account of courage and compassion that will touch your heart.

Re-Navigation: In the atmospheric setting of a Welsh island, Julia embarks on a Spiritual Development course, seeking answers and a sense of purpose. Surrounded by new friends, she begins to question the emptiness she feels inside. As relationships grow and secrets emerge, Julia is confronted with life-altering choices that come with a price. With passion and uncertainty intertwining, Julia must decide the true value of her desires and the sacrifices she is willing to make.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

THE COLORS OF LIFE

A NOVEL COLLECTION

SUE PARRITT

CONTENTS

A Question of Country

Acknowledgments

1. The Letter

2. No Turning Back

3. Learning Australian Ways

4. The Good Weekend

5. Bush, Scandal and the Vagaries of Language

6. Lunch and an Unexpected Development

7. Christmas Day Australian Style

8. Wild Weather

9. New Year Celebration

10. Late Summer Shock

11. Mid-winter Woes

12. Hopeful Horizons

13. The Best Laid Plans…

14. …of Mice and (Wo)men Often Go Awry

15. A Surreal Homecoming

16. Trials and Other Tribulations

17. The perils of Efficiency

18. Harrow Street

19. Shangri-La Shocks

20. Resurgence

21. Rejection

22. Fight or Flight

23. Acceptance

24. Consolidation

25. Suburban Shocks

26. A Means to an End

27. A Limited Season

28. New Decade, New Direction

29. Change of Scene, Change of Pace

30. Slow Progress

31. Success and Complications

32. Changeable Weather

33. The Consequences of Climate Change

34. Unravelling

35. Retreat

36. Intrusion

Feed Thy Enemy

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Afterword from the Author

Re-Navigation

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2023 Sue Parritt

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2023 by Next Chapter

Published 2023 by Next Chapter

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

A QUESTION OF COUNTRY

To Mark, beloved husband for more than fifty years (November 1969-) and fellow migrant (July 1970)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to Miika Hannila and the team at Next Chapter for having faith in my writing.

THE LETTER

Anna remembered arriving home that drab December day with all the clarity of freshly washed glass, details of those long-ago hours embedded deep in her blood and bone. They marked the birth of a tempestuous relationship that, after fifty years, still coloured the palette of her life.

A pile of Christmas post greeted her sleet-sodden shoes, precipitating a clumsy dance away from new doormat to threadbare carpet. After depositing her handbag and shopping bag on the hall stand, she picked up the letters and skimmed through the small envelopes, smiling at the still unfamiliar address written by friends and relatives. At the bottom of the pile, a brown foolscap envelope caught her attention and her smile broadened as she noted the typed delivery details and London postmark. Gripping the envelope between gloved fingers, she made no attempt to retrieve the seasons' greetings that fell like giant snowflakes over the faded floral carpet. A draught from the open door prompted swift action from her right foot, while her left hand reached for the light-switch, positioned for some unknown reason at least three feet from the door. Spread-eagled, she slid on Aunt Maud's Christmas greetings, smudging the spidery fountain pen script, then tilted towards the hall-stand. Grateful for heavy Victorian furniture, she grabbed the polished edge to prevent a fall. Bird-light, the brown envelope fluttered down to join paler varieties on the carpet.

Balance restored, Anna kicked off her shoes and bent to pick up the scattered post. There seemed little point in holding the brown envelope up to the light; the hall was too dingy to see anything useful at this hour of the winter afternoon. Besides, they had agreed one shouldn't know before the other; they must open it together, share the welcome or unwelcome news. Unfortunately, she knew Joseph would be late home, as his area manager's monthly visit was bound to culminate with drinks in the pub on the Friday before Christmas.

* * *

Two hours and ten minutes later, dinner ready and kitchen cosy from gas cooker and paraffin stove, she was still waiting to slit the thick brown paper. Propped on the kitchen bench next to salt and pepper, the envelope seemed to mock her deliberate busyness, its glued-down flap and unknown contents never far from thought or eye.

Suddenly, she heard the front door hit the wall with a thud. A second thump and footsteps pounding up the narrow hall confirmed Joseph's arrival.

'I'm home, darling,' he called as usual, entering the lounge.

From the kitchen doorway Anna watched him toss his coat onto a lounge chair and walk sleet-softened leaves across the cracked kitchen linoleum. Chilled lips kissed, whisky breath warmed, wet hair dripped over her candy-striped apron.

'What's for dinner?' he asked, releasing her and walking over to the cooker.

'It's arrived,' she answered breathlessly, steering him away from saucepans and frying pan.

'What?' he asked, then noticed the envelope.

Side by side, they perched on the yellow kitchen stools he had made just weeks before, their heads close together, the letter held taut between winter-pale fingers.

'Yes!' he cried.

'Yes,' she echoed.

He lifted her lightly, twirling her away from kitchen claustrophobia. Elated, they danced through sparsely furnished lounge and across narrow hall to cluttered bedroom. In the kitchen, boiled potatoes cooled, baked beans congealed, sausages stuck to shiny aluminium. The letter from Australia House lay abandoned on the kitchen bench.

NO TURNING BACK

A taxi transported the young couple from station to docks, depositing them opposite a series of tin sheds that leant against one another for support. Anna could just make out the word Customs on the peeling sign above a half-open door. After unloading their two suitcases, the driver wished them good luck and sped away in a cloud of black exhaust fumes.

Behind the customs shed, the ship loomed large against a hazy summer sky, her sleek white lines punctured by portholes. Anna noted the yellow funnel, the lifeboats strung like lanterns along the starboard deck, and had to look away, not from regret at leaving homeland, family and friends, but to restore her identity. The ship overwhelmed her, snatching her insignificant life, all her dreams and fears reduced to numbers typed on a blue shipping contract. Last minute nerves, she presumed, recalling her parents' barely concealed tears at the station, their forced smiles as the train pulled away from the platform. They had declined a dockside farewell, her father maintaining it would be too upsetting for her mother.

Joseph's parents lived more than a hundred miles from the port and didn't own a car, so coming to Southampton docks wasn't an option. In-law goodbyes had been made weeks earlier, at the end of a difficult weekend cramped in a small terraced house along with Joseph's three siblings and a smelly dog. Since their engagement a year before, Anna had tried to become friends with Alan and Stella, but it proved an uphill battle, her mother-in-law in particular making no secret of the fact she disapproved of Joseph's choice.

At first, Anna had been miffed by the snide comments on her lack of style, her penchant for reading serious literature, her parents' Methodism, but as the wedding day drew near, she had taken refuge in the clandestine appointment scheduled for the second day of their brief London honeymoon. A late November wedding offered limited locations for newly-weds keen to preserve their savings, so they had booked three nights in a modest London hotel, their primary objective being ease of travel to Australia House in the Strand. Months earlier, they had completed emigration forms in the privacy of Joseph's bedroom – he shared a flat with two friends – and, following a swift response from Australia House, attended a specified doctor's surgery for medicals. A letter advising that both of them met Australian health standards followed soon after. By mid-October, the would-be migrants had progressed to the final hurdle, according to the cheerful young man Joseph had spoken to on the telephone when arranging the obligatory interview to coincide with their honeymoon.

Anna anticipated a formal atmosphere, stuffy civil servants sitting behind a desk firing questions, but the two immigration officers – youthful and genial – had spent most of the time enthusing about life in the 'lucky' country, their speech peppered with enticing descriptions of beach and bush. Joseph's queries about job prospects were answered with a casual, 'No worries, mate, plenty of work for those willing to work hard,' followed by friendly advice to 'learn Aussie ways quick smart' and 'don't whinge.' Listening to subsequent dialogue, Anna surmised that 'whingeing Poms' were a despised breed, destined to be ostracised at social events and in the workplace.

'Just remember, comparing Australia with Britain is a futile exercise,' the younger officer declared towards the end of the interview. 'In my book, the two countries represent opposite ends of the spectrum. Britain is an old, overcrowded nation that has had its day. Empire in tatters, high unemployment, industry in decline, grim-faced people struggling to make ends meet. Australia, on the other hand, is racing up the achievements ladder, a vibrant new nation destined for greatness.'

Although Anna admired his enthusiastic patriotism, she couldn't help feeling his views were somewhat biased. Thousands of Britons might be seeking a life elsewhere, but fifty-five million remained. Prudently, she remained silent, playing the role of compliant new wife that the officials appeared to require. There would be time later, in the privacy of their hotel room, to chew over the interview, laugh about over-embellished language and, if necessary, express long-held feminist views. The final question almost proved her undoing and it took immense effort to remain serene and respond to what she considered downright impertinence.

'How many children do you plan to have?' the older man asked, leaning towards her.

Anna and Joseph exchanged glances. Babies were not on their immediate agenda. They had discussed children but agreed that starting a family could wait for some years, with Anna being just twenty-two and Joseph twenty-four next birthday.

'Three at least,' Anna replied, in what she hoped was a convincing tone.

'Sooner rather than later?' A supercilious smile sauntered over the official's thin lips. 'Populate or perish, you know.'

'Give us a chance,' Joseph retorted. 'We've only been married for two days!'

* * *

Waiting in the customs queue, Anna recalled the officials' laughter and thought of the packets of contraceptive pills safely stored in her capacious shoulder bag. The previous week, a visit to her local doctor had secured a prescription for three months' supply, to cover the travel period plus give her time to register with an Australian GP. There would be no unplanned pregnancy in the Fletcher household.

The queue shuffled forward, the occasional suitcase opened for inspection, passports scrutinised, or, in some cases, the documents of identity supplied by Australia House at no cost to those without a current passport. One-way ticket, Anna mused as Joseph handed over the document, their particulars hand-written and two unsmiling faces glued inside black-bordered boxes at the bottom. It had taken Anna several attempts to acquire suitable photographs. Cramped in a photo booth, her sombre expression twice dissolved into giggles as the camera snapped. 'What the hell are you doing in there?' Joseph had asked, standing on the other side of the curtain clutching his strip of four acceptable snaps.

'Make your way to the ship now,' the customs official instructed, indicating a door to his left.

Joseph reached for her hand. 'This is it, my girl.'

Anna grinned. 'No turning back now, we're signed and sealed.'

* * *

Once on board, they shuffled along narrow, crowded corridors, searching identical doors for their allotted cabins. B deck contained mostly four-berth cabins; families were housed on lower decks. Married couples without children were segregated, four wives in one cabin, four husbands in the next. A ten-pound assisted passage didn't cater for the appetites of newly-weds. In the heady days of mass migration, it was a case of cramming in as many as possible. Every week, a ship carrying hundreds of hopeful emigrants left Southampton for the long journey south.

They didn't linger to meet cabin mates, preferring to be on deck when the ship sailed. According to Anna's much-travelled Aunt Maud, departure would bring ceremony and celebration. Streamers, a brass band, ship's horn booming, crowds on the wharf waving, cries erupting the moment a tough little tug began to tow the huge ship away from the dock.

A sailor pressed a coloured streamer into Anna's free hand as Joseph pulled her along the deck. An unbroken line of passengers stood by the rail waiting for the signal to throw. Anna would have to toss her streamer high and hope the wind carried it down to the dock, not into some stranger's backcombed tresses.

'In here!' Joseph shouted, pushing her through a tiny gap.

She clutched the rail and glanced at the upturned faces gathered for farewell. Thank God her parents had decided against coming to see them off. Uninhibited, she could relish the moment, punch the air in triumph, jump for joy, yell until her lungs were fit to burst. 'Goodbye, goodbye! Off with the old, on with the new, Australia, here we come!'

Yachts shared the liner's passage down Southampton Water, heading for the Isle of Wight or out into the Channel for a run down the coast. The island slipped by; patchwork quilt fields edged with high white cliffs. Open water from now on, first port of call the Canary Isles, specks of rock in the wide Atlantic. No cruise through the Mediterranean for their batch of migrants, as the Suez Canal had been closed to shipping since the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Nowadays, the voyage to Australia took five weeks instead of the pre-war four, heading down the west coast of Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean, with only two stops before reaching the western Australian port of Fremantle.

The first few days passed in a blaze of sunshine, the hours between meals occupied with swimming in the pool, deck games and exploring the ship. During the brief visit to Tenerife, largest of the seven Canary Isles, Anna and Joseph, along with others from the ship, took advantage of a cheap coach tour to view Mount Teide, the third largest volcano in the world. Other passengers opted to walk the streets of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, admiring well-preserved colonial buildings.

One week into the lengthy voyage, many passengers remained afflicted with seasickness and on several occasions Anna and Joseph sat alone in their section of the dining room, much to the disappointment of waiters trying to offload five courses. For the first time in their lives, they ate grilled steak, relishing each succulent mouthful. Joseph demolished four pieces at one meal, delighting the Italian waiter. 'Troppo sottile,' he said, indicating Joseph's thin arm. 'Eat, eat!'

Crossing the Equator brought fun and celebration, Anna volunteering to be one of half-a-dozen young women dressed in grass skirts, bikinis and floral garlands, cavorting on deck for the 'crossing the line' ceremony. Her reward was an ornate certificate written in Latin, featuring Neptune astride a horse, trident in hand.

But three days into the Southern Hemisphere, the Lord of the Sea shook his three-pronged spear, scattering passengers to the safety of bar and coffee lounge. Cold rain lashed empty decks and sun and stars retreated behind dark storm clouds as the ship ploughed through huge seas.

Barriers appeared around the dining tables as the ship neared the Cape of Good Hope, but food, especially soup, still had to be consumed quickly to avoid spillage. Once again, beanpole Joseph enjoyed copious portions.

Cape Town harbour provided two days respite from the wild seas, yet for Anna, the majestic Table Mountain and beautiful coastal scenery were marred by the ever-present injustice of apartheid. From the moment she stepped onto South African soil, the consequences of racial segregation smothered her like a malevolent cloud. Twenty-two years of living in a prosperous seaside town had not prepared her for the sight of children begging in the streets.

In the doorway of a large department store, a young black woman clad in a ragged cotton dress sat on the ground, holding out a tiny baby swaddled in sackcloth. Behind the woman, fluorescent lights illuminated rack after rack of tailored coats, sleek jersey dresses and jaunty hats. Shocked, Anna stood staring, unable to raise her eyes from the infant's puckered face. Wind gusted up the street from the harbour, lifting the veil of her youthful naiveté, tossing it high into the charcoal clouds shrouding city and flat-topped mountain.

'Not this shop,' Joseph said, unaware of her distress. 'We need a supermarket for washing powder.'

Still focused on extreme poverty, she allowed him to lead her down the street, remembered too late her failure to augment the few coins in the woman's begging bowl.

In the supermarket, it took some time to locate laundry products, as the first shopper Anna approached muttered, 'No speak white woman,' before scurrying away. Joseph said perhaps the woman hadn't understood the question, but Anna thought this unlikely.

Back on board for lunch, the young couple from Yorkshire whom they had befriended didn't seem to share Anna's horror and bewilderment. Small boys begging in the street had annoyed rather than upset Clive and Janette, as had the sign in the post office, which prevented them joining the shorter Blacks Only queue.

Later that evening, the absence of a similar sign caused further irritation when the two couples tried to enter a city nightclub and were refused entry by a scowling doorman of gigantic proportions. Through the windows, crowds of brightly dressed people could be seen dancing to a jazz band. 'Pity about that,' Joseph remarked as they retreated, 'the music sounded fabulous.'

'Bloody stupid rules,' Clive retorted. 'Thank God we're not moving here.'

Janette slapped his wrist. 'Keep your voice down, we don't want to upset him.'

By contrast, the Whites Only venue further up the road had recorded music – a poor selection, the English couples considered, having grown up on the Beatles and Rolling Stones. Bored, they left after an hour and decided to walk back to the ship, rather than take a taxi.

As they neared the wharves, the distance between streetlights widened, traffic diminished, and shop windows became grey shapes in the dim moonlight. They walked briskly, jacket collars turned up against the cold night air. Not far from the ship, a group of young men stood talking and smoking in a darkened shop doorway. The English foursome passed by without giving them a second glance, half-a-dozen youths congregating on a Saturday evening being a not uncommon sight in their respective hometowns. Footsteps quickening behind them were barely discernible above friendly chatter; within minutes, they were surrounded.

The men were tall and thin, dark faces and clothing melding with the shadowed street. Black hands clutched the white men's lapels, pulled them apart, plunged deep into inside pockets. Anna saw Clive tense in anticipation of a blow that never came; Joseph stood immobile, his face a mask of stoicism. Expletives sliced the night sky when hands surfaced empty of coin or note. Anna stood to one side, staring straight ahead, the handbag containing their cash and identity document slung across her chest. Cursing intensified, becoming vivid descriptions of what the men wanted to do with white women's bodies. Only words, Anna told herself, letting them float over her head. Beside her, Janette blanched, fear flooding her blue eyes like white-hot tears.

Still swearing, the young men retreated, leaving the four British migrants shaken but unharmed. Later, leaning on the ship's rail gazing at a star-filled sky and twinkling city lights, Anna found it hard to reconcile the beauty of place with the ugliness of manmade prejudice and privilege. But greater than fear, shock or sadness was the sense of indignation she experienced during a coach trip around the city the following day. Halfway through the tour, the coach slowed to allow tourists a good view of Groot Sur Hospital where Doctor Christian Barnard was performing the first heart transplant operations. After gazing at the white monolith for a few moments, a middle-aged woman sitting in the aisle seat opposite Anna asked the driver several questions about the long-term prognosis for transplant patients. The driver supplied only vague answers, unwilling or unable to deviate from his set spiel.

The coach moved on past grand houses surrounded by high walls topped with barbed wire, then descended a steep hill to a group of buildings reminiscent of the customs sheds on Southampton docks. Slowing a little, the driver explained proudly, 'This is the hospital we have provided for the blacks.'

The woman opposite leapt to her feet. 'It's a dilapidated tin shack! You should be ashamed of yourselves. How can you condone this appalling apartheid?'

'You English don't understand the situation here,' the driver retorted, putting his foot on the accelerator.

The woman began to speak again, but this time the man beside her placed his hands firmly on her shoulders and, pushing her back down in the seat, said softly, 'Now is not the time to be a good Quaker, Ruth.'

Other words burned in Anna's mouth. She wanted to jump up and congratulate the woman for saying what was surely on all their minds, but something held her back. It was not fear of the driver reporting inappropriate remarks to the authorities, or risking an accident by flying around sharp bends, but rather the embarrassment of standing out and causing a scene. So instead, she reached for Joseph's hand, squeezed it and swallowed hard to dislodge the impotent words stuck in her throat.

Discussing the incident later over coffee in a bar on A deck, Joseph remarked that while there was a need for action, there was also the need to know the right time for action. Anna agreed, little knowing his words would return to haunt her in the Nineties' post-apartheid world.

* * *

Boredom set in after the Cape Town interlude, with the vast Indian Ocean needing to be crossed before they reached land. They had to endure two weeks of bad weather, the swimming pool closed, walks around the deck reduced to brief, wind-jarring forays. Alone at night in her narrow top bunk, Anna longed for Joseph's arms, lingering kisses, fingers fondling soft breasts.

One evening, they struck up a conversation with an Australian couple who were returning home following a year working in England. After the usual pleasantries and discussion of the apartheid regime in South Africa, talk turned to the ship in general and cabin accommodation in particular. As paying passengers, the Australians had a cabin to themselves and offered to lend it for an hour or two, following Joseph's remark on shipboard separation. He accepted the unusual offer without hesitation, forcing a blushing Anna to flee to the nearest bathroom.

* * *

Naked on a top bunk – they didn't like to use the lower bunks inhabited by the Australians – Anna and Joseph giggled like adolescents snatching sex behind absent parents' backs. Limbs became entangled, Joseph's feet kept hitting the cabin wall and Anna couldn't get comfortable. It wasn't a total waste of time, but they decided not to request the cabin again. Making love to order in the cramped confines of a top bunk lacked appeal.

Next morning, the Australian couple approached them on deck. 'Have a good one, mate?' the husband asked, digging Joseph in the ribs.

Mortified, Anna looked at her feet, wishing the wind would whisk away Joseph's reply.

* * *

The port of Fremantle provided the migrants' first glimpse of Australia. Busy wharves, ugly warehouses, sea gulls cawing; it could have been Southampton docks all over again, except for blue sky of a brilliance seldom experienced during an English summer, let alone winter.

Along with numerous other passengers, Anna and Joseph caught a train to Perth, rattling through pockets of industry and rundown houses to the city centre. The shops were similar to those they'd left behind, although Anna was bemused to find “Manchester” meant sheets and towels. In Kings Park, they sat on a bench eating egg and lettuce sandwiches for lunch, the plain fare enjoyable after weeks of rich shipboard meals. Admiring tropical flora occupied the remainder of the afternoon, Anna revelling in the lush foliage. Foolishly, she ignored the gravel paths, staining her white canvas shoes as she ran across freshly watered lawns.

Returned to confined ship space, Anna wished they had disembarked permanently, like the passengers they observed standing on the wharf with suitcases at their feet. Impatient, she wanted to embrace Australian life without delay. 'Two more stops before we can begin our new life,' she moaned to Joseph, as they tramped the deck. 'Why do days at sea pass so slowly?'

'Patience is a virtue,' he began, reciting the first line of a poem Anna had once quoted to him. 'Besides, as far as I'm concerned, our new life began the moment we stepped on board.'

'We could have come by air,' she muttered, recalling Joseph had been the one to insist that travelling by ship would be the better option because they could bring all their belongings, rather than one suitcase each. Not that they possessed a great deal. Their first home had been fully furnished, a set of yellow kitchen stools the only addition.

'And leave our wedding presents behind?' he countered.

She thought of the hideous dinner-set Stella had given them for Christmas: thick china, gaudy colours, odd-shaped cups and bowls. 'I'm pleased we could bring that beautiful little table your uncle made,' she said, choosing tact over criticism. 'All the same, I'll be glad to reach our final destination.'

'Me too.' Joseph slowed his pace. 'My main concern is employment. Our savings won't last long if we don't find work quickly.'

Anna reached for his hand. 'Don't worry, I'm sure we'll land something within a couple of weeks. There were plenty of vacancies listed in that newspaper we read this morning.' During breakfast, the purser had announced that Australian newspapers from several states were available in the main lounge and advised passengers to peruse the relevant publication.

Joseph looked over her head at interminable blue water. 'I know, but I can't apply for a job from the middle of an ocean.'

Anna almost quoted the patience poem, thought better of it and said instead, 'Don't forget that chap behind the counter at Australia House said Brisbane is a city on the move.'

Joseph squeezed her hand. 'I love your cheerful optimism, darling.'

* * *

Brisbane, located halfway up Australia's eastern seaboard, had been chosen as the Fletchers' new home not for climate or job prospects, but because their sponsors, Roger and Mary Gittens, lived there. In 1970, childless married couples who migrated to Australia needed a sponsor to vouch for their good character and provide accommodation on arrival. Families were sponsored by the Australian government.

After completing his electrical engineering apprenticeship, Joseph had secured a position in the small company where Roger worked. The two soon developed a good working relationship, so Roger's announcement that he was emigrating to Australia with his family had been disappointing. Interested in working abroad at some future date, Joseph had asked Roger if they could correspond. Two years later, Roger and Mary had readily agreed to sponsor the Fletchers, even though they hadn't met Anna.

Rough weather buffeted the ship as it crossed the Australian Bight and Bass Strait, sending all but the hardiest hurrying below decks. Passengers breathed a collective sigh of relief on leaving the heaving Southern Ocean behind at the narrow entrance to Port Philip Bay. Winter rain squalls swept the exposed decks, the sky gunmetal grey, but at least the water remained relatively calm. For Anna and Joseph, the day in port – the city of Melbourne was located at the head of the bay – turned into almost a repeat performance of Perth. After taking a train from the docks into the city, they looked around the shops, munched sandwiches in the Botanical Gardens, then clattered past factories and small brick houses back to the ship. The weather proved the exception, showers and a cold wind bending the bare-limbed trees that lined the city streets. More like England than sunny Australia, Anna thought, thankful their sponsors didn't reside in Melbourne.

After leaving the expanse of Port Philip Bay, the ship headed east, travelling parallel to the Victorian coast. Whatever the weather, Anna ventured on deck for hours, marvelling at golden beaches, wild surf and grey-green forests stretching as far as the eye could see. How she longed to leave her footprints on those pristine beaches, dive into foaming waves, hike through unfamiliar trees. Admittedly, she felt a little apprehensive at the sight of immeasurable eucalypt forests. Oak, ash, elm and birch were the trees she knew, the solid legacy of a tenth-century Norman conqueror desiring a place to hunt. The New Forest of childhood picnics, wandering ponies and timid deer had held no fear for her, its roads and paths leading to thatched-roofed cottages, old stone churches and cosy pubs. However, the dense Australian forests appeared to have no beginning or end; a tangled labyrinth she felt sure would foil even the most intrepid adventurer.

Before long, the ship turned the corner and made its way up the east coast towards Sydney. Small towns and what looked from a distance like farmland, dissected the previously endless forests. The beaches remained the same, miles and miles of sand fringed with white surf. Every now and then, a headland jutted into the ocean, breaking the line of surf. Anna leaned on the rail, drinking in details of the immense continent she soon would call home.

* * *

Fast asleep in their separate cabins, Anna and Joseph missed the ship's passage through the heads into Sydney Harbour and would have also missed the Coat-hanger bridge if the captain hadn't announced its approach as they ate breakfast. There was an immediate mass exodus from the dining room, every migrant wanting to be on deck when the ship steamed under the famous bridge.

Just before they reached the bridge, the woman standing beside Anna at the rail pointed out the controversial – in her opinion – opera house under construction on Bennelong Point, a mass of scaffolding, exposed concrete beams and unusual shapes. Anna nodded and smiled, unwilling to comment on a structure she knew nothing about. Beyond the bridge, tower blocks stood sentinel as ferries scurried over blue water, transporting workers to offices and shops. Then, as the ship approached its Circular Quay berth, the same woman squealed with delight and began waving. 'That's our Eric down there!' she exclaimed. 'Come all the way from Parramatta to meet us.'

Long after the engines had ceased their relentless throb, Anna and Joseph waited impatiently for the signal to disembark. Officials organised the migrants into three groups: those destined for Sydney hostels, those being met by family or friends at the quayside and those travelling beyond Sydney. Last to leave were migrants destined for Queensland. Following disembarkation and customs processing, they were crammed into an ancient bus and driven to a migrant hostel, there to while away the hours until the overnight train for Brisbane left Central Station.

Villawood was a rude awakening. Anna's romantic dreams of the new land began to crumble as she carried her suitcase to the Women's accommodation – the shipboard separation order remained in force – one of half-a-dozen rusting Nissen huts dotting dusty ground. Metal-framed bunks lined the walls and metal chairs with torn vinyl seats leaned against a shabby Formica-topped table. Most of the bunks were occupied by older, grey-haired women who stared at the newcomers with grim expressions. No one spoke or raised a hand in greeting, so Anna dumped her suitcase in a corner and fled the sorry scene.

Joseph was waiting for her outside the Men's hut, his face a picture of misery. 'I feel like an enemy alien interned for the duration,' he said, as she took his hand.

Anna leaned closer and said quietly, 'Just now, I saw some inmates sitting outside a hut. Stout middle-aged women wearing frumpy dresses, thick black stockings and headscarves, jabbering away in a language I didn't even recognise.'

'Probably Eastern European or Russian.'

'How long do you think they have to live here?'

'Dunno. Weeks, months maybe. I suppose it depends on available accommodation and whether they've got a job.'

'Thank God for your friend Roger. If I had to stay in this dump, I'd head straight for the airport and catch a plane out of here.'

Joseph smiled and mussed her hair with his free hand. 'We've got to stay for two years, darling, that's part of the deal. If we return home before then, we have to pay back the fare for the outward journey.'

'I know, I know.' She pouted. 'But I do think we could have been taken to a less depressing place. Villawood doesn't exactly give a positive first impression of Australian life.'

'Cheer up, it's only for a few hours.' Joseph squeezed her hand. 'Let's check out that large hut. Might be a chance of a cup of tea over there.'

'We should be so lucky,' Anna muttered.

The ruddy-faced official who'd escorted their group emerged as they reached the building. 'Good timing,' he said, holding the door open. 'Lunch is on now. Bit stodgy, but I guess you Poms are used to that sort of food.'

Anna stiffened and was about to utter a curt response when Joseph pushed her forward. 'Bloody cheek,' she said through clenched teeth, as they entered the dining area.

Long and narrow, with few windows and furnished with two rows of rectangular tables separated by an aisle, the room reminded Anna of the hut left over from the war where she'd endured school dinners at secondary school. Almost all the tables were occupied, but, after collecting their meals from a couple of sour-faced women standing behind a stainless-steel counter, Joseph located a space at the end of a table near the kitchen.

Several headscarves nodded in their direction as they took their seats and an elderly man offered a toothless grin. Anna smiled back, then turned her attention to the mess of food fast congealing on a thick white plate: grey-tinged mashed potato, slices of fatty meat, peas and a bright orange item of unknown origin. Gingerly, she scooped up some potato and peas, swallowing without tasting. The food was bland and overcooked; she toyed with a piece of meat but baulked at the orange mash. Soon, defeated, she put down her knife and fork and sat back in the seat to wait for Joseph to finish his meal.

Suddenly, a woman on Anna's left snatched the discarded plate and flashed a smile before hoeing into the leftovers. Anna tried hard not to stare at the loaded fork shovelling food into fleshy lips. Several loud belches followed the final mouthful. Fortunately, Joseph responded without delay to a tug on his shirt sleeve, ensuring a quick exit.

Late in the afternoon, the same ancient bus transported the new migrants from Villawood to the central railway station, where they boarded shabby wooden carriages resembling museum pieces. The train travelled north through unknown, unseen territory, uncomfortable seats and crying children making the night seem endless.

Dawn brought a modicum of relief, pale light revealing vistas of grey-green trees, brown grasslands and grey road ribbons. It looked to Anna as though someone had shaken a giant feather duster over the entire countryside. Devoid of primary colours, the land appeared worn, a crumbling continent locked in ancient ways. The promised golden future faded like a Polaroid photograph left too long in the sun.

Called to the dining car for breakfast, Anna dismissed her pessimistic thoughts and turned her tired eyes to toast and tea. Standing in a long queue, jostled by weary parents with fractious children, she counted the hours that lay ahead of them on the drab cattle-truck train and hoped Brisbane would present a brighter picture. She had just reached the head of the queue when the woman behind the counter knocked a jug in her direction, sending milk cascading over her blue linen coat. Almost in tears – the coat was brand new – Anna dabbed at the sodden linen with a handkerchief.

'Please could I have a cloth to wipe this up?' she asked.

A dirty dishcloth flew over the counter without an apology in tow.

Back in her seat, Anna tried to ignore the smell of drying milk, pressed her face against Joseph's chest and closed her eyes.

* * *

The next thing she knew, Joseph was shaking her awake. 'Nearly there, darling. Have a look at our new home.'

She peered out at cloudless sapphire sky, swaying green palms, red iron roofs, white fences. Turning to face him, she smiled her relief.

South Brisbane Station continued the vibrant colour scheme. Baskets filled with exotic blooms hung from an iron roof, palm trees in large pots dotted the platform, huge tropical ferns clung to wooden posts. Delighted and amazed, Anna lingered in the train doorway, much to Joseph's annoyance as he'd spotted Roger on the platform.

Warm greetings further revived Anna's spirits and she followed Roger and Joseph, already deep in conversation, out of the station to a large estate vehicle she would learn was known by the initials HG. Roger, clad in a bright open-necked shirt, tailored shorts and socks to the knees, made Anna feel overdressed in her linen “summer” coat. If this was Brisbane winter attire, what did Roger wear in summer?

The final segment of their interminable journey across the world, entailed a forty-minute drive north through the city centre and sprawling suburbs. In the back seat, Anna craned her neck to observe the vagaries of Brisbane architecture. Most of the houses were raised above ground level on wooden or concrete piers – “stumps” in Australian, Roger said. Some were high enough to store a car underneath while others sat close to the earth. Verandas varied from large structures with fancy wrought-iron edging, to narrow strips barely wide enough to hold a chair. Painted steps with handrails led from front gardens to verandas; at the top of older dwellings stood a pair of doors supported by large posts. A fence surrounded each house, top and bottom wooden rails painted white with wire mesh in between. Occasionally, a brick wall broke the pattern.

Front gardens – she couldn't see into the rear – were a bit of a disappointment after the station's tropical flora. Lawn predominated, with a few shrubs dotted about or a single tree in the middle. Concrete or gravel paths led straight from gate to steps; in some instances, two adjacent strips with grass in between served as tracks for a car parked under the house.

Roger and Mary's front garden was a welcome surprise: flowering shrubs behind a low brick wall; two squares of grass each containing several trees and a mass of bright green ferns peeping out from under the veranda and steps. Mary, slim and tanned, stood leaning on the veranda rail, her smile and sleeveless summer dress radiant as the garden foliage.

After brief introductions – neither Joseph nor Anna had met Mary before – the new arrivals were ushered into a large, open plan room, comprising a lounge with a dining area behind. 'Make yourselves comfortable,' Mary said, gesturing towards the two armchairs placed opposite a settee. 'I'll go and make tea.'

'Thanks. I didn't go much on train tea.'

Mary smiled and disappeared behind a short wall, into what Anna presumed was the kitchen.

The two men remained standing, having resumed the conversation begun at the station, so Anna took the chair furthest from the front door and sat quietly surveying her surroundings, like a potential house purchaser. Unlike most British homes, the front door led straight into the living room and, from the distinct sounds of tea-making coming from behind the wall, no door separated kitchen and dining area. The layout reminded Anna of the holiday house in Cornwall her parents rented year after year; a flimsy structure designed for summer living. From her chair near a side window, she could see a hallway leading, she imagined, to bedrooms and bathroom. She remembered that Roger and Mary had two children and wondered if they had a spare bedroom.

'Tea's up,' Mary announced, interrupting her thoughts of sleeping arrangements.

Anna accepted the proffered mug and slice of cake with well-meant thanks.

'I'll show you to your room when we've had this,' Mary said, sitting in the adjacent chair after distributing her wares. 'It's downstairs. You'll be the first visitors to use the rumpus room. Roger's only just finished it.'

Her mouth full of delicious moist orange cake, Anna could only nod.

'It's a good thing you were coming to stay,' Mary confided, leaning towards her guest. 'Otherwise the room still would be a bare concrete floor covered with piles of fibro sheets and timber.'

Anna's eyes widened. 'Roger actually built the room?'

'Oh yes, everyone's building under the house these days. It's a great way to gain space without spending a fortune. The bed folds up, so when we don't have visitors, the kids can use the space as a playroom.'

'What a good idea.'

'I've built a padded bench seat on one wall,' Roger added. 'Lift up the seat and there's storage underneath for the kids' toys.'

'Brilliant,' Joseph remarked. 'I had no idea you were into DIY.'

Roger grinned. 'I've learned lots of new skills, mate, since living in Australia. Over here, neighbours muck in to get a job done. Share a few stubbies and put on a barbie afterwards, that's all they ask.'

'Sounds like real community spirit.'

Roger nodded. 'The Aussies are good sorts, pretty laid back. They love a beer and a yarn. It doesn't take too long for them to accept newcomers, although you must be prepared for a bit of teasing, especially about your accent. And for God's sake don't criticise the place or you'll get tagged “a whingeing Pom”.

'Thanks for the advice.' Joseph turned back to his tea.

Mary patted Anna's arm. 'You're looking tired. I don't suppose you got much sleep on that ancient train?'

'No, what with children crying, people coughing and terribly hard seats.'

'You sat up all night? Why didn't you pay for a sleeper?'

'We didn't realise you could,' Joseph replied. 'Besides, we've got to be careful with our money. Who knows how long it'll take to get jobs?'

'Talk to you about that this evening,' Roger remarked, rising to his feet. 'I must get back to work now or the boss will be spitting chips.'

'Thanks for everything, Roger. I don't know what we'd have done without you. That migrant hostel in Sydney where we spent the day was pretty grim.'

'No worries, and it's Rog here, mate. You'll be Joe, Aussies abbreviate everything!'

Anna smiled, but secretly hoped she wouldn't become Ann. It would remind her of a fat girl in sixth form: clammy hands, greasy hair and terrible BO. Poor thing. No one ever wanted to partner Ann Levin during dance lessons.

* * *

The newly built room under the house served the visitors well during their two-week stay. The only snag was the lack of insect screens – the room wasn't quite finished – but they soon learned to apply a spray called Aerogard before going to bed. Apart from the occasional mosquito – swarms in summer, Roger maintained – there were few insects, much to Anna's relief. Adopting the Aussie penchant for teasing those once-termed “new chums”, over succeeding days Roger regaled his visitors with stories of dangerous snakes hiding in piles of timber and huge spiders lurking in shoes, waiting to pierce unsuspecting Pommy skin. Never again would Anna put on a pair of shoes without shaking them first.

LEARNING AUSTRALIAN WAYS

Spring arrived on the first of September, according to the local radio, but as far as Anna and Joseph were concerned, the season remained the same: warm sunny days with only occasional rain and cool nights. Each morning, on opening the Venetian blinds in their first-floor flat, they exclaimed anew at the brilliant blue sky and golden sunlight.

Weekdays allowed scant time for sky-gazing. Dawn meant quick showers, a hurried breakfast and dressing in clothes suitable for their respective work places. Their visions of pounding city streets day after day looking for work had proved erroneous, Joseph filling a vacancy for an associate engineer in Roger's office immediately, and Anna slotting into an administrative position at a city college two weeks later.

Finding a flat to rent was also accomplished without angst. Blocks of flats known as “six-packs” were being constructed throughout the suburbs within a five-mile radius of the city centre to cater for the burgeoning population and most were affordable. Roger – Anna couldn't bring herself to call him Rog – had taken them flat-hunting on the Saturday after they arrived and, apart from one decidedly grotty place in an older block, all seemed suitable.

They chose a one-bedroom furnished flat at the rear of a recently completed block. The kitchen was poky, with only a couple of cupboards above and below the sink, a cooker and a huge white refrigerator that looked ridiculous in the small space. The furniture was basic but sound: a vinyl-covered lounge suite, a Formica-topped kitchen table with four metal-legged chairs and a Formica bedroom suite. But far more important to Anna than style, or even comfort, was the fact that everything was brand new. No one had slouched on the chairs or settee, no one had slept in the bed, the tiles around the shower gleamed and the linoleum floor tiles were clean and bright.

Back in Britain, their first home together, a two-bedroom flat on the ground floor of a formerly grand nineteenth-century house, had reeked of age and neglect. The bathroom walls ran with condensation, the lounge suite was so filthy and worn that Anna's mother had insisted on buying loose covers, and underneath peeling wallpaper, a previous tenant had pasted strips of aluminium foil in an attempt to keep out the damp. The rent had been exorbitant, almost half of Joseph's wages, but they'd had little choice, rental accommodation being scarce in the town. The alternative, beginning their married life in her parents' home, had been dismissed as unworkable.

Roger thought the rent for the new flat rather steep and urged them to look around a bit longer, but Anna insisted it was worth every dollar and Joseph concurred, as the large garage underneath the flat was an unexpected bonus for a practical man. Anna was more intrigued by the dual concrete washing tubs located at the rear of the garage behind a concrete block screen. The letting agent referred to this space as 'the laundry' and advised that washing clothes in the bathroom or having a washing machine in the kitchen were forbidden. The landlord, a cheerful, rotund Italian who owned the entire block, didn't seem the type to instigate such a rule. Later, Anna learnt from a neighbour that state regulations stipulated a separate laundry room in every dwelling. At the rear of the block, two large metal rotary washing lines, an Australian invention known as a Hill's Hoist, stood in the middle of a patch of grass.

Like the Gittens' home, the flat's front door opened directly into an open plan living room and lacked the familiar letter slot. The post, referred to as “mail”, was delivered to a brick wall studded with numbered metal boxes located to one side of the driveway, by a “postie” on a motorbike. Such a different world over here, Anna mused, as she hung out washing or collected mail from their box.

Although the bus stop for the city route was only five minutes' walk from the flat, Anna and Joseph soon realised that a car, far from being a luxury, was an absolute necessity in a sprawling city where, apart from small blocks of flats, detached houses set on quarter-acre blocks were the norm. The few shops within walking distance supplied only meat, bread, and newspapers; the nearest supermarket involved a ten-minute bus ride.

Transport to work was also a consideration. Buses, although frequent, took their time to reach the city centre, meandering through numerous suburbs instead of taking a direct route. The friendly chap in the neighbouring flat, Davo, suggested they use the suburban rail, as the nearest station was only a short drive away and the train would have them in the city in half the time. He offered them a lift to and from the station in his gleaming Holden Monaro until they acquired their own car. Anna accepted gratefully, but the times didn't suit Joseph, so he continued to take the bus.

Several weeks after moving into the flat, they set off by bus to visit the car yards that displayed their merchandise on both sides of the main road a few miles north. Excited by the prospect of owning a car at last and, if she was honest, influenced by rides in Davo's magnificent Monaro, Anna wanted to buy something sporty, preferably red, but as usual Joseph had more sober ideas, reliability and value for money being his primary concerns. The first major argument of their married life took place on the pavement outside Value Vehicles, with Anna extolling the virtues of a red convertible and Joseph defending the suitability of a grey Holden sedan. Eventually, after she had flounced off, threatening to catch the bus home and Joseph had shouted after her that acting like a spoilt adolescent would get her nowhere, they both apologised and, hand in hand, crossed the road to Mighty Motors, “home of Brisbane's best car deals”.

After inspecting numerous cars and test-driving two, they settled on a 1965 white two-door Vauxhall Viva with red seats. Joseph handed over the hundred-dollar deposit and arranged to bring the balance of three hundred the following Monday after work. 'It's no trouble keeping the office open late,' the salesman assured them. 'Good to have an excuse to miss the kids' bath time.'

Isn't that just typical of a man? thought feminist Anna.

The car purchase put a dint in their Commonwealth Bank savings account, but at least they knew the money could be replaced quickly. Their initial wage packets had astounded them, containing almost twice what they'd earned in England and living costs, especially groceries, were cheap. For their first Sunday dinner in the flat, Anna had walked to the local butcher and purchased an enormous leg of lamb for a ridiculously small sum. It had taken all week to eat the leftover roast meat, so she made a mental note to invite Roger, Mary and the children to share a meal on the next occasion she purchased a joint of meat.

Fruit, vegetables, meat, fish, everything grew to enormous proportions in Queensland, the result, she assumed, of a sub-tropical climate. The same seemed to apply to the Australian people, as most of the passengers on the train, or those seen during the occasional lunchtime spent sitting on a bench in the Botanical Gardens, were well above what Anna considered average height and weight. Sharing her observations with Joseph one evening, she felt rather foolish when he gave a rational response that should have been obvious. 'Not climate, silly, diet. Cheap top-quality meat, cheese, fish, plus fresh fruit and veg guarantee healthy growth. Don't forget we grew up on post-war rations.' He grimaced. 'Remember overcooked cabbage, mashed potato and a single slice of stringy meat if you were lucky?'

'As if I could forget!'

'And we were fortunate,' he continued, wagging his finger at her as though addressing an ungrateful child. 'Think of the thousands of displaced people stuck in camps all over Europe after the war. What they would have given for our rations.'

'A Jewish family moved into the flat up the road when I was eight,' Anna said quietly. 'When I asked why Mum was giving them clothes and taking them the vegetables Dad had grown for us, she said they had survived years of harsh living in camps, so they needed help. I couldn't understand why living in a camp was so bad until Dad explained.'

Joseph glanced at the discarded piece of steak – a bit tough – on his dinner plate. 'A friend at school came from Holland. He told me his parents had survived the war by eating tulip bulbs. I didn't believe him at first.'

Anna reached across the table to take his hand. 'We're fortunate on two fronts. Firstly, to have grown up never knowing hunger, and secondly, to have been given the opportunity to come to Australia.'

Joseph nodded, stabbed the meat with his fork and began to chew thoughtfully.

* * *

The small Vauxhall Viva looked lost in a garage built for the sizable Fords and Holdens favoured by most Australians. Nevertheless, Joseph proudly showed it off to Davo and ignored his comment that it was a sheila's car. Anna named the car Vivienne after an old school friend, but Joseph referred to her as Viv, in deference to the Australian penchant for abbreviation.

The Saturday following her arrival, Viv inadvertently caused an embarrassing incident when Joseph decided a wash and polish would improve her appearance. By ten o'clock, the temperature had already climbed to twenty-eight degrees Celsius, so he donned a pair of the brief shorts known as “stubbies”, a confusing label for a Pom who had just learnt that small bottles of beer went by the same name.

Already sporting a decent tan, Joseph looked appealing as Anna emerged from the garage carrying a full laundry basket and made her way to a Hill's Hoist. In between pegging clothes and towels, she watched his firm brown body bend and stretch over the white car, noting the way the sun had bleached his thick curly hair, and the line of pale skin revealed when he leaned over the bonnet.

Balancing the empty laundry basket on her hips, she sauntered towards the car. A moist kiss on the base of his spine sent the sponge flying and the bucket of soapy water rolling down the driveway. Twisting around, his frown evaporated when he saw Anna standing close by, dressed in her Saturday morning cleaning outfit of brief shorts and singlet top with no bra underneath. She gave a seductive smile, stepped forward and ran a warm hand over his chest. 'I should go and get the camera, you look gorgeous!'

He took her face in his wet hands and kissed the tip of her nose, her forehead, her laughing mouth.

'Not just gorgeous,' she murmured when he released her, 'but good enough to eat.' His cheeks reddened, and she wondered why, since no one else was about. Then she saw the reason for his embarrassment. The tight shorts did little to disguise his erection and the landlord was fast approaching up the driveway!

'Can you hold this for a minute?' she asked, pushing the empty laundry basket into his arms. 'I've just remembered something else I meant to wash.' Barely stifling a giggle, she fled across the concrete driveway and up the steps into the flat.

'Buon giorno, Joe,' she heard Mr Martelli call. 'Nice car you are having but basket, she no good for cleaning, mate, too much holes!'

Anna crept out of the flat and stood by the balcony rail, determined to hear Joseph's response.

'I was just going to retrieve the bucket.' Joseph dumped the basket on the bonnet and pointed to the bucket lodged against the driveway wall halfway down.

'She is bella,' Mr Martelli remarked.

'Yes, not bad for a first car.' Joseph stepped away from Viv.

The landlord laughed, a deep-throated rumble that shook his round belly, making it strain against already taut shirt buttons. 'No car, Joe, I am talking wife!'

Anna retreated inside, loath to be caught eavesdropping.

THE GOOD WEEKEND

The acquisition of Viv the Vauxhall Viva enabled not only travel beyond local shops or city centre, but also allowed the new migrants to embrace that sacrosanct Australian tradition, 'the good weekend.' The first question Anna was asked at work on a Monday morning was, 'Did you have a good weekend?' the words slurred together into a string of barely comprehensible syllables. Without exception, her colleagues lived for the weekend, spending Friday morning tea break and lunchtime discussing what they had planned and Monday's breaks relating what they had accomplished. There appeared to be various categories of good weekend, with sport – watching it, mainly – being number one and visits to the coast coming a close second. “Coast”, Anna soon learnt, was a general term applied to both the Gold Coast south of Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast to the north.

Viv, gleaming in spring sunlight, transported her owners north for their initial good weekend to a small island connected to the mainland by a bridge. According to Anna's colleagues, Bribie Island was a popular destination and not too far for a first venture into the unknown. As they drove over the bridge, Anna could hardly believe the magnificent vista unfolding before them. Sparkling turquoise water lapped a lengthy strip of white sand, while behind the beach stood a tangle of trees, interspersed at intervals by the linear lines of small holiday houses. Sailing boats skimmed over the water, fishing dinghies bobbed beside the bridge, children splashed in the shallows.

Anna wanted to find a parking spot the moment Viv reached the island, but Joseph had other ideas. 'This is the passage side,' he said, in an authoritative tone. 'Families favour this side, it's safe for children. We're going to the other side, the ocean proper. Surf's good over there.'

'I hope it isn't too rough.'

'You'll be fine. Anyway, we'll be swimming between the flags today. I wouldn't want to take any risks on our first day at the coast.'

Anna considered asking the significance of flags but kept quiet, reluctant to show her ignorance. Conversation turned to suntan cream, hats and the need to purchase a beach umbrella before their next visit.

Soon, they were striding along a wide beach, the fine white sand tickling their bare toes. Umbrellas of varying sizes and colours dotted the beach; beneath each one a polystyrene or metal box, an “esky” in Australian parlance. Packed with ice, eskies kept beer and food cool and were deemed essential for beach or bush outings. Umbrella owners reclined on beach towels or low folding chairs within arms' reach of their eskies, their faces tilted to the warm spring sunshine.