3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Sprache: Englisch

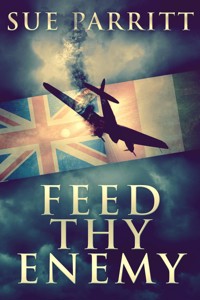

In this heartwarming tale, a British airman risks it all to feed a starving, war-stricken family.

Thirty years after serving in World War II, middle-aged Rob takes a holiday in Italy. Struggling with PTSD and depression, the journey sparks a dream that brings long-stifled memories back to the surface.

Flashbacks to the war days, of Rob's attempts to save a famished family, trigger suppressed memories of war, love, and sacrifice. But can he find the strength to confront the problems in the present?

Based on a true story, Sue Parritt’s Feed Thy Enemy is a raw, heartwarming account of courage and compassion.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

FEED THY ENEMY

SUE PARRITT

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Afterword from the Author

You may also like

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2019 Sue Parritt

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2021 by Next Chapter

Published 2021 by Next Chapter

Edited by Marilyn Wagner

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is based on a true story. The names of all characters have been changed to protect those persons still living. Some places and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

In loving memory of my dear parents, Nick 1913-1978 and Jean 1921-2009

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to Miika Hannila and staff at Next Chapter for enabling me to share my father’s story.

ONE

They are in the garden when the phone rings, he, bent over a spade digging up potatoes, she, pulling out weeds with great gusto and throwing them onto the adjacent lawn. He watches her sprint across the grass and up the concrete path alongside his new wooden shed, her shapely sun-browned legs moving with the same power and grace she displays when swimming or cycling. Fifty-three last birthday, Ivy retains the trim figure Rob admired all those years ago in the goods office at the central railway station. A petite woman, she was and remains, a complete contrast to his first post-war girlfriend, the tall, voluptuous redhead seated at the adjoining desk, long pale fingers tipped with scarlet nails, striking typewriter keys as if her life depended on it. That relationship was over almost before it began, Edna’s avant-garde attire and flamboyant behaviour overwhelming a mild-mannered railway clerk, still recovering from four years of war service. Why had he asked her out in the first place? Almost thirty years on, he still doesn’t know the answer.

Leaning on the spade, Rob smiles as he remembers the day one of the older clerks took him aside following one of Edna’s more colourful tales related over lunch in the cramped staff room. ‘Robert, I think you should know that both girls caused great consternation in the office during the war whenever a troop-carrying train pulled in to the station,’ the fifty-something clerk confided in a low voice, colour dusting his pale cheeks as though the very mention of Edna and Ivy’s exploits made him somehow complicit.

Too late, Rob wanted to say, thinking of his evening date with Ivy, but being a relatively new employee, remained silent.

‘The moment boots were heard marching across the platform,’ the clerk continued, ‘the girls would rise from their desks, fling up the office windows and resting their breasts on the windowsill, wave and shout warm welcomes. Responses were always greeted with requests for billet addresses in exchange for promises of evening outings and a tantalising glimpse of cleavage.’ The clerk leant closer. ‘Summer troop arrivals were the worst, the girls attired in thin blouses or dresses with low necklines during warm weather.’

Rob found it difficult to maintain a serious expression, being fully aware that Ivy had dated men from Commonwealth countries and numerous Americans besides during the war. Prior to the clerk’s disclosure, they had been dating for weeks.

Still smiling at his wife’s wartime escapades, Rob picks up another potato and tosses it in the old enamel basin at his feet. His back is stiff from repeated bending, so he straightens up, wincing as he stretches arthritic fingers. Through the nearby bay window, he can see Ivy perching on the arm of an easy chair, holding the telephone handset to her ear. He’s wondering whether to go inside to make a pot of tea when a familiar gesture, fingers raking through her short curly hair, alerts him to sudden irritation. Displeased, he wants to wrench the handset from her fingers, berate the caller who has destroyed the tranquil ambiance of their shared spring afternoon.

When Ivy returns to the garden, Rob senses her altered disposition long before he notices pursed lips and the heightened colour dusting cheeks already tanned from spring sunshine. Disappointment hangs over her like storm clouds mustering in a summer sky.

‘Our cruise has been cancelled,’ she announces in a clipped voice.

‘Whatever for?’ he asks before she can enlighten him.

‘The shipping line’s gone bankrupt.’

Swearwords froth in his mouth, but before they can be expelled, neighbour Harold appears beside the garden shed that backs on to their shared fence. Harold Jenkins is the epitome of courtesy and never swears. Curses metamorphose into banknotes that hover above Rob’s head just out of reach. ‘Does that mean we’ve lost our money?’

Ivy shakes her head. ‘Only the small deposit. Our travel insurance will cover the rest.’

‘Thank God for that. So, what now, how can we organise another holiday in just a couple of weeks? I imagine the insurance money will take an age to come through.’

Ivy smiles. ‘Not a problem on both counts, love. We’ve been offered a two-week coach tour of Italy and the travel agent said her company is happy to cover the cost until our insurance pays up.’

‘I see.’ He tries to envisage well-ordered olive groves, unspoilt villages clustered on hillsides, ancient ruins shimmering in summer sunlight. He fails, scorched earth and smoking ruins making his eyes water.

‘She wants a definite answer today.’

Frowning, Rob thinks of the friends who suggested he and Ivy join them on the cruise. ‘We’d better phone Alf at once,’ he says, drawing a finger across his left cheek to wipe away moisture. ‘He and Dawn may not have been offered the coach tour and it wouldn’t seem right to go without them.’ Looking down, he studies the potato resting on damp soil at his feet.

‘Our travel agent and theirs have already liaised. Alf and Dawn are happy to take the coach tour.’

Lifting the spade, he slices the potato in half. ‘Decision made then.’

Seated either side of the dining table, a well-ironed cloth disguising its shabby surface, husband and wife concentrate on miniscule lamb chops served with generous portions of home-grown potatoes and broccoli. Silence suits them both, she, dreaming of ancient monuments, art galleries and cathedrals; he trying to blot out disturbing wartime memories.

‘Rome, Florence, Venice,’ Ivy exclaims suddenly, raising her eyes heavenward. ‘It’s going to be wonderful!’

Rob neatly arranges his knife and fork before lifting his head and looking across the table. ‘I’m not certain I want to go.’

Sea-green eyes flash fury. ‘You agreed this afternoon. It’s a bit late now to change your mind. The booking will have been made.’

‘But I wanted to cruise the Aegean, explore tiny islands, experience the wonders of antiquity.’ He sighs. ‘Sun, sea and glorious food.’

Ivy jabs a last potato with her fork. ‘There’ll be plenty of sun and glorious food in Italy, plus countless antiquities. And the travel agent said most of this tour follows the coast. Besides, we can’t let Alf and Dawn down.’

In no mood for argument, Rob picks up his knife and fork to continue eating, each mouthful chewed and swallowed without acknowledgment of taste. Unblinkingly, he endeavours to focus on gradually emerging white china as images of the Italian coastline move in slow procession through his mind. Messina, Salerno, Naples, Anzio – targets on maps for Allied eyes only.

Wartime maps and holiday destinations are far from Rob’s thoughts the following Monday, as he unlocks the small door at the rear of Harrison’s Supermarket and steps into a dark storeroom. After reaching for the light switch, he waits a moment for the fluorescent tube to connect, then lifts a grey dustcoat from a nearby hook, replacing it with his sports jacket. The dustcoat is faded from copious washing and fraying on the hemline but at least it protects the well-pressed navy-blue trousers, white shirt and tie he always wears for work. Unnecessary neatness for a storeman, he acknowledges, but essential for his self-esteem. Buttoned up, he skirts a pile of cardboard boxes to retrieve the hand trolley he had parked out of harm’s way the previous Friday, discovers to his annoyance that someone has shifted it. ‘Damn cleaner most likely,’ he mutters, moving to check the other passageways.

Abandoned in the centre aisle, the trolley lies on its side, waiting for an unsuspecting staff member to trip and skin a leg or ankle on its rough metal base plate. Resisting the urge to aim a kick at its balding tyres, Rob bends to right the beast, gasps as pain shoots through his lower back. Bend your knees and keep your back straight, he thinks, recalling his doctor’s advice. Heavy lifting, bending and stretching have taken their toll during his two years of employment at the supermarket. At the end of each working day, each muscle throbs and he longs to immerse his weary body in a warm bath, an unlikely proposition during summer months when the central heating that also heats water has been turned off and they have to use the immersion heater instead. Baths are a once a week affair in the Harper household, the cost of heating sufficient water daily, prohibitive.

Taking small careful steps, Rob pulls the trolley to the end of the passageway where tomatoes from the Channel Isles wait to be transferred to the vegetable section, then slowly lowers the base plate to the concrete floor. ‘Bend, lift, stack,’ he repeats throughout the wearisome task, the mantra taking his mind off aging muscles. Sounds of imminent opening time filter through the swing doors leading from storeroom to supermarket: high-pitched laughter from teenage cashiers whose mini-skirts leave nothing to the imagination; heavy footsteps in the meat section adjacent to the doors as Terry the butcher, red-faced and rotund, surveys and reorganises his domain.

Trolley piled high, Rob inches his way forward, his breath coming in short sharp bursts, as he navigates an adjoining passageway stacked to the ceiling with cardboard cartons. At the first turn, hecautiously sets the trolley upright to wipe already damp palms on his dustcoat prior to tackling the next aisle. Wooden crates containing trays of Jaffa oranges from Israel arrived late on Friday and are creating an extra hazard by protruding into the walkway. ‘Damn,’ he exclaims when a careless sideways shuffle results in contact with the crates’ rough edges. Pulling up his right trouser leg, he examines the skin above his sock, notes beads of blood decorating a two-inch scratch, an annoying injury only minutes into an eight-hour day.

As he inhales the fragrance of sun-kissed oranges, his gaze shifts to the purple cardboard trays visible through slatted timber. Manufactured with indentations to keep each orange separate from its neighbour, the trays prove useful for storing produce from his own tiny orchard – three apple trees, one plum, one peach, one pear. Mr Harrison has no objection to his taking home any number of trays as non-perishable rubbish is collected from supermarket bins on a weekly basis. Every autumn Rob uses newspaper to wrap apples and pears individually, ensuring his crop keeps for months stored beneath the household’s three beds. Peaches are eaten as they ripen, the old tree rarely producing a decent crop. Ivy bottles some of the Bramley cooking apples for pies, crumbles or sauce; others she leaves under the beds to be cooked at a future date. Baked apples, their cores removed and replaced with sultanas and brown sugar, are one of Rob’s favourite puddings. Licking his lips, he wonders what delight Ivy will serve this evening. His first question on returning home is always, ‘What’s for pudding, love,’ first course of little consequence to a man with a sweet tooth.

After checking that blood hasn’t trickled into his sock, Rob grips the cracked rubber handles and begins to manoeuvre the trolley into the slightly wider passage leading to double swing doors. A tricky right, the operation requires total concentration, so he slows to a crawl, and is almost home and dry when the trolley clips a pile of cartons containing tins of pineapple. They fall sideways in a perfect demolition, crushing several crates of oranges and sending Rob flying. Sacks of King Edward potatoes save him from serious injury, but he feels dazed and remains sprawled on lumpy hessian when the manager rushes in.

‘Not again!’ The man’s bulk towers over the mound of crushed crates and boxes. ‘How many times have I told you to be careful with that trolley?’

‘I’m so sorry Mr. Harrison.’ Rob struggles to his feet.

‘Sorry won’t replace damaged stock, Robert. I’ll see you in my office when you’ve cleaned up this mess.’ And kicking escaped tins aside, he strides towards the doors.

Defeated, Rob sinks to his knees and hangs his head.

Dinner is a subdued affair, Rob seeking the courage to confess he’s been sacked; Ivy distracted by a letter from their daughter, Sally, who lives in a small town fifty miles away. ‘A new sister on the orthopaedic ward is making life difficult for the younger nurses,’ Ivy remarks, looking across the table. ‘Sally says her constant criticism and impatience has led several student nurses to resign before their final exams. Such a waste of all that training.’ She sighs. ‘Poor Sally, if only I could just pop over and give her a hug,’

Rob raises his head, tempted to answer that hugs will be off the menu permanently soon, Sally having decided to join older sister Frances and her husband James in Australia. Reluctant to raise what remains a sensitive subject, she’ll be leaving the country within three months, he concentrates instead on spearing strips of cabbage with his fork.

‘I’d hoped she could get home soon,’ Ivy adds, ‘but she hasn’t a free weekend before we go on holiday.’

Cutlery slips from Rob’s fingers onto the plate, splattering the cream tablecloth with globules of gravy. ‘We can’t go on the tour now,’ he blurts out. ‘I’ve lost my job.’

Ivy flinches, then leans forward, green eyes demanding an explanation.

‘That damn trolley again.’

A long silence follows, Ivy’s mouth moving in slow motion as she digests bad news and a last forkful of cabbage.

‘You could still go,’ he says, relieved to have thought of a solution. ‘Alf and Dawn would keep you company.’

‘And leave you alone for fourteen nights.’

‘I could get some sleeping pills from Doctor Hughes.’

‘Sleeping pills aren’t the answer, Rob. A holiday would do you good.’

‘But I need to find another job.’

‘You need to get out of the house and I don’t mean into the garden or the shed.’

Rob pushes his plate into the centre of the table and gets to his feet. Two steps and he has turned on the television set tucked in a corner away from the fireplace; a further three and he’s seated in his favourite armchair, adjacent to the tiled hearth. The BBC news has already started; he stares at the familiar presenter, ignores the nearby clatter of plates and cutlery, the muttering about having to wash a tablecloth that was clean on this evening.

The national news bulletin, bleak as usual with its reports of industrial disputes, power cuts and IRA bombs, matches his mood, confirming what he has believed ever since the nineteen-seventies began. Everything in Britain is falling apart, the economy crippled by strikes and excessive wage demands, unemployment at its highest level since the war and the Troubles in Northern Ireland out of control. Slumped in the armchair, a draught from the open door leading to the hall, chilling the bare skin between socks and trousers, he shudders at the prospect of searching for work in such a depressed environment. There’s no doubt about it, their daughters are the smart ones, abandoning the sinking ship before it’s too late. When explaining her reasons for emigrating, Sally maintained she saw no future for herself in Britain, a sentiment Rob endorsed. Frances and James have sponsored her, offering a home with them, which speeded up the immigration process. Secure accommodation plus nursing qualifications should ensure a bright future for a twenty-one-year old.

In preparation for her arrival, James, a practical man, has built a room in the space under the house between the garage and laundry, a combination lounge and bedroom with French doors leading out to the rear garden. Meanwhile, Frances has purchased a second-hand wardrobe and bed and is saving up for carpet and a new three-piece suite. Clearly, she expects her sister to stay for some time. For her part, Sally has volunteered to make curtains in between looking for work as Frances detests sewing of any kind.

Rob envisages the whole family gathered together under one roof at some future time, but, before long, reality pulls him up short. Even if he wanted to leave his homeland, there is no point in a sixty-year-old with an unacceptable employment record and a long history of mental illness applying to emigrate to Australia. He sighs loudly and for the first time in years, his thoughts return to a distant decade, a distant land and the crash in the Sahara Desert that should have ended his life.

After a protracted but successful dogfight with a German fighter, they were heading back to their base in south-western Egypt, when a second Messerschmitt appeared from nowhere. The RAF pilot, Colin ‘Smudger’ Smith, veteran of countless desert ops, immediately took evasive action and as the Martin Baltimore levelled out hundreds of feet below, he and his crew believed they had outrun the enemy. But the Messerschmitt 109 had a distinct advantage over its opponent, a fuel injection system that allowed the fighter to dive quickly without losing speed, and Smudger soon realised they were heading straight into the enemy’s path. Prompt action by both pilots avoided a collision, but gunfire from the machine gun mounted on top of the Messerschmitt’s nose cone, peppered the Baltimore, sending it corkscrewing over massive dunes tinted blood-red by the setting sun. As Smudger tried to regain control, black smoke bled into the cloudless Egyptian sky, a stain on an otherwise perfect desert backcloth. A final flash of flame seared the right wing and the Baltimore plummeted earthward, coming to rest, nose first, in a massive wind-moulded sand dune.

Inside the aircraft’s metal and Perspex dorsal turret, rear gunner Sergeant Robert Harper gingerly lifted his head and surveyed his surroundings before descending into the smoke-filled fuselage. Minutes later, his head, still encased in flying helmet and goggles, emerged from a side hatch. Gripping the edge of the hatch, he levered himself out and jumped on to the sand. He landed on hands and knees close to the blackened wing and quickly manoeuvred into a sitting position, his back to the now silent aircraft. Incessant desert wind wailed a sorrowful refrain that filtered through his Mae West life-jacket and blue-grey battledress, even penetrating the black boots half-buried in sand. Scrambling to his feet, he turned to grab the wing, thick flying gloves protecting his hands from heated metal, and pulled himself back to the fuselage. ‘Smudger, Jim, Stuart,’ he called, peering through the open hatch, his voice hoarse as though he had been shouting throughout the entire afternoon.

There was no response, so he forced his body back into the aircraft, determined, despite the risk of imminent explosion, to rescue his injured colleagues. After a brief interval, he resurfaced ashen-faced, blood smeared over bare hands, fell to his knees in a futile posture of prayer. Anger oozed from every pore, sizzled on exposed skin. ‘They’ve bloody well abandoned me,’ he yelled, finding his voice at last. ‘Left me alone in this godforsaken desert. What the hell did they think they were doing?’ He straightened his back, shook his fist at the empty sky. ‘We were a team, a bloody good team, so why didn’t you take me with you, you selfish bastards?’

Barely conscious of the slim fingers stroking his wrist, Rob continues to stare at the television screen. ‘Please come to Italy with me,’ Ivy pleads, her breath a wisp of breeze on his sun-reddened cheek. ‘How can I celebrate our twenty-sixth wedding anniversary on my own?’

At last Rob raises his head but can’t bring himself to turn and face her. ‘You deserve a medal putting up with me for so long,’ he mutters, glancing at the framed photograph on the mantelpiece – small daughters and parents enjoying a long-ago holiday on the Channel island of Guernsey.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ she counters.

‘No, I mean it. Our marriage hasn’t exactly been a bed of roses. All those years when I was in and out of hospital and you were left alone with the girls, struggling to manage on the sickness benefit. And even when I was working, the jobs were poorly paid. Remember?’

Ivy remains silent.

‘We couldn’t have bought this house if you hadn’t earned extra cash by taking in guests from the hotel next door to the flat when they’d overbooked. I’ll never forget how you slept on a blow-up mattress on the lounge floor with Frances night after night, so I could have her bed. And what about all those foreign students you cared for once we’d moved here? Washing, ironing, cooking, taking them on outings. It must have been a chore, summer after summer. There’s no doubt about it, Ivy, you’re the one who’s kept the family together.’

Stroking stops and the pads of her fingertips press into his skin. ‘Oh Rob, please don’t bring up all that again. Just come with me to Italy. The holiday is paid for and afterwards we can manage for a while with my job and your war pension.’

It took them long enough to give me my dues, he reflects, recalling annual train journeys to a shabby London office, where he had to plead his case before three grim-faced military men sitting, stiff-backed, behind a heavy wooden table. Fifteen years of deliberations, fifteen years after demob to achieve a minor victory. The RAF medic’s upper-crust voice repeats in his head: ‘Mr. Harper, we shall be recommending to the Ministry of Pensions that the further disability Depressive State be accepted as attributable to service and added to Stomatitis Ulcerative, which has already been accepted. You will be informed within six months of the Ministry’s decision and your War Pension Order Book annotated as necessary.’

‘A pittance,’ he says aloud, twisting around to face his long-suffering wife. ‘Twelve shillings a week for nearly four years of war service.’

‘Better than nothing,’ Ivy answers in her usual optimistic manner. ‘How about a cup of tea and a slice of cake while we study the tour itinerary?’

TWO

The remainder of the evening passes without further discord, a favourite comedy programme diverting Rob’s attention from the wartime memories evoked by photographs in a holiday brochure Ivy picked up from the travel agent. Night is another matter, quietness and darkness joining forces to create an unbearable atmosphere that only minutes after climbing into bed, infiltrate a mind still reeling from the unexpected events of the past forty-eight hours. Questions come thick and fast, lacking sufficient space between them for considered responses. A limited timeframe – only fifteen days remain before they’re due to fly to Italy – providing an inadequate period for Rob to consider employment options. There’s no way he can register for unemployment benefits and then announce he’ll be unavailable for job interviews due to a two-week holiday abroad. Age is another concern that dominates his restless thoughts. By the time they return home he will be sixty-one, too old to apply for any job requiring sustained physical work. Previous occupations come to mind, a lengthy list proclaiming to anyone perusing his employment history, his inability to retain a position for, at the most, more than a couple of years.

Beside him, Ivy snuffles in her sleep, a reminder of his own insomnia. The prospect of sleep unlikely, he slides out of bed, quietly locates slippers and dressing gown and creeps from the room. At the foot of the stairs, he spends a few moments deciding whether to make a hot drink or try reading the library book commenced a few days earlier. Cocoa wins out, a heaped teaspoon of sugar added to enhance the flavour. He carries the steaming mug into the dining room and positions it on the hearth tiles while he draws back the curtains. Bathed in pale moonlight and deep shadow, his beloved garden slumbers peacefully. The evening breeze has died away, nothing stirs in vegetable beds or fruit trees. For several minutes, he stands leaning against the wide curved windowsill, calmed by the thought of runner beans, carrots and tomatoes growing quietly, proof he can contribute something to the household.

Seated in his armchair, he cradles the mug in both hands and sips slowly, grateful for the soothing full-cream milk warming throat and stomach. A digestive biscuit would add to the comfort, but he has left his dentures in a glass on the bedside cabinet and can’t risk waking Ivy by retrieving them. Dunking would solve the problem, but for some reason, tonight he doesn’t relish the thought of soggy biscuit floating in cocoa.

After replacing the empty mug on the hearth, he lies back in the chair, hoping to doze until dawn, but his eyes feel gritty as though sand has blown from beach to cliff-top, through municipal gardens and winding streets into the dining room. He blinks rapidly to dispel the irritation, sighs as a second wave of sand distorts his vision. Reading is also out of the question; he wouldn’t be able to focus. He tries to relax, push unbidden thoughts into the garden where shadows can swallow black bitterness.

Pinpricks of light begin to flicker behind closed eyelids, portents of migraine that threaten to destroy even a modicum of peace. Annoyed by this additional sign of neurological weakness, he rises quickly and with scant regard for the early hour, stomps through dining room and kitchen to what the family refer to as the back door, even though it’s situated in the centre of a side wall. He pauses to pluck the key for the shed, from a hook by the sink, before crossing to the door. The old lock groans as he turns the key always left in situ; then, as he pulls the door towards him, hinges creak despite the care and attention he regularly gives them. Undeterred, he walks out into the cool night air, avoiding contact with the Ford Anglia parked behind high latticed gates and approaches the shed with quickening steps. After fumbling in his dressing gown pocket for the key, he manages to open the well-oiled padlock and slide back the bolt with barely a sound. Automatically, he reaches for the light switch, taking care not to trip over the step as he moves inside. Light from a one hundred-watt lamp floods the small space, shutting out dreaded darkness. He pulls the door shut and exhales deeply.

Before long he’s perched on an old stool facing the single window, his hands resting on the workbench he constructed from old floorboards found in the loft, his mouth concentrating on the squares of Cadbury’s dairy milk chocolate melting on his tongue. He keeps a bar or two in an old biscuit tin stored on the shelf beneath the bench, chocolate perfect for wet weekend afternoons when gardening proves impossible and Ivy sits chatting in the dining room with her friends. He could join the women for afternoon tea, there’s always a good spread of homemade cakes and biscuits. No one would mind, he’s known most of the women for years, Ivy having a predilection for long-term friendships, but he can’t face the inevitable questions about work or health.

He’s peeling silver foil from the last two squares of chocolate, when a sound on the roof stays his hand. More a beat than a flap, the noise continues at regular intervals, becoming louder as though the neighbour’s cat has climbed onto the shed and is drumming its paws on the green roofing felt. Furious, he slips off the stool and makes his way outside, careful to close the door behind him. There’s no way he’ll allow the detested feline sanctuary in his shed; it causes enough havoc in the garden. Looking up, he spots the reason for chocolate interruption – a piece of roofing felt has come loose on a corner and is banging against a rafter in pre-dawn breeze. Quickly retracing his steps, he selects nails and a hammer from the workbench drawer, places them in his dressing-gown pocket before picking up the stool and carrying it out to the concrete pad in front of the door.

Slippered feet carefully balanced on the stool, he has finished securing the roofing felt and is gazing up at a myriad of stars when footsteps behind him induce a total body freeze. Light from the shed illuminates the scene, no chance of slipping unnoticed into shadow.

‘Come on Rob, that’s enough star-gazing for tonight,’ Ivy urges, her soothing voice a welcome panacea for night terrors.

Fingers release their grip, the hammer clatters to the ground. Holding on to the doorframe, he eases himself into a sitting position, then slides off the stool and stands in the pool of light as though uncertain what to do next.

Smaller fingers reach around him, switch off the shed light and close the door. A bolt slides into place, a padlock clicks shut. Perfectly composed, despite being woken in the early hours by the sound of hammering, Ivy slips her left arm around Rob’s waist and leads him into the house.

The following afternoon, Doctor Hughes accedes to Rob’s request for medication to calm anxiety, although he refuses the request for a stronger anti-depressant. ‘My advice is to leave your worries behind for two weeks and enjoy the holiday,’ he says, reaching for a prescription pad.

‘That’s what my wife says,’ Rob remarks as the doctor scrawls.

‘She’s right you know.’ The doctor smiles as he hands over the prescription. ‘Italy in early summer will be marvellous.’

Rob manages a fleeting smile.

Three nights of dreamless sleep improve Rob’s mood and restore his energy levels to such an extent that, by Friday afternoon, he has dug over two garden beds, mown the lawn and planted more vegetables. Eager to help Ivy, who works two full and three half-days a week as a secretary in the office of a large department store, he has also taken advantage of fine weather to do several loads of washing. Standing by the dining room window, he looks out at clothes and sheets flapping in the breeze, pleased with his day’s work. If the weather remains fine the following day, he’ll suggest a drive in the country. They can pack a picnic lunch and folding canvas chairs, sit in dappled sunlight in one of the nearby New Forest’s picnic grounds. The purchase of a second-hand Ford Anglia five years earlier has broadened their horizons and Rob will be forever grateful to his late mother-in-law for the legacy that enabled them to pay off the remaining mortgage and buy their first car.

Soon after the primrose-yellow car was installed behind the driveway gates, he sold the moped used for travelling to and from work, relieved he no longer had to face journeys up and down the lengthy bypass, exposed to wet or freezing weather. Two years later, daughter Frances drove them both to work in the opposite direction, Rob having secured a temporary clerk’s position with the company she’d joined as a clerical officer at age seventeen. Sharing the car didn’t bother him – Frances often asked to borrow it on Friday and Saturday evenings – she was a good driver and he understood why her boyfriend James couldn’t afford a car on an apprentice electrician’s wages.

Despite fine weather, the picnic fails to eventuate, Edna, Ivy’s friend from their railway office days, being home on leave from Zambia where her husband works as an engineer. Rob declines the invitation to afternoon tea, knowing the two women will appreciate having time to catch up on news and waves Ivy goodbye as she pedals off on the short ride to her friend’s bungalow near the beach.

Gardening, followed by watching cricket, occupies the entire afternoon. On warm summer days, Rob carries the television set into the garden, threading an extension lead through an open window. In between weeding and planting, he sits in a deckchair, retrieved from the shed, to watch play. Sometimes neighbour, Harold, leans over the fence to ask the score, but that seems to be the extent of his interest in the game; he never accepts Rob’s invitation to join him.

Engrossed in the English captain’s well-played century, Rob fails to hear the side gates open or a bicycle trundle towards the shed, and almost jumps out of the deckchair when Ivy calls a bright, ‘hello, I’m back.’ She leans the bicycle against the shed before walking towards him. ‘Good match, love?’

‘Excellent. We should win this one.’

Behind him, Ivy places her hands on his shoulders. ‘Good afternoon then.’

He reaches up to pat her right hand. ‘I haven’t been sitting here all afternoon, you know. I weeded a patch by the pear tree as well.’