1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

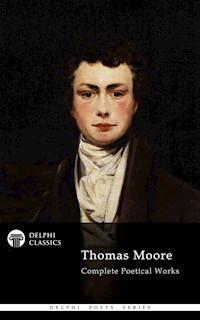

In "The Complete Poems of Sir Thomas Moore," the renowned Irish poet and lyricist offers a rich tapestry of verse that weaves together themes of love, longing, loss, and national identity. Moore's poetic style is characterized by its melodic quality, romantic imagery, and a profound emotional depth, all of which firmly situate his work within the Romantic literary movement of the early 19th century. The collection reflects Moore's mastery in blending personal sentiment with broader cultural narratives, encapsulated in celebrated pieces such as "The Irish Melodies," which reverberate with the strains of Irish folklore and political consciousness. Thomas Moore (1779-1852), a pivotal figure in Irish literature, was influenced by his own experiences as an expatriate and a witness to the socio-political upheaval in Ireland. His education at Trinity College Dublin and friendships with contemporary literary giants fueled his desire to articulate the complexities of the Irish identity through verse. Moore's life was marked by the tension between his English patronage and his loyalty to his Irish roots, a dichotomy that reverberates throughout his poetry. "The Complete Poems of Sir Thomas Moore" is essential for lovers of poetry and those interested in the interplay of nationalism and romanticism. This collection not only charts the evolution of Moore's poetic voice but also invites readers to explore the rich cultural heritage that shaped his work, making it a vital addition to both literary studies and personal libraries. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A comprehensive Introduction outlines these selected works' unifying features, themes, or stylistic evolutions. - The Author Biography highlights personal milestones and literary influences that shape the entire body of writing. - A Historical Context section situates the works in their broader era—social currents, cultural trends, and key events that underpin their creation. - A concise Synopsis (Selection) offers an accessible overview of the included texts, helping readers navigate plotlines and main ideas without revealing critical twists. - A unified Analysis examines recurring motifs and stylistic hallmarks across the collection, tying the stories together while spotlighting the different work's strengths. - Reflection questions inspire deeper contemplation of the author's overarching message, inviting readers to draw connections among different texts and relate them to modern contexts. - Lastly, our hand‐picked Memorable Quotes distill pivotal lines and turning points, serving as touchstones for the collection's central themes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Complete Poems of Sir Thomas Moore

Table of Contents

Introduction

This collection presents, in a single compass, the full range of Thomas Moore’s poetic achievement, from his earliest experiments to his mature sequences and late satirical energies. Its purpose is both archival and interpretive: to preserve the texts, prefaces, and performance cues Moore attached to many works, and to display the breadth of a career that moved with equal fluency among song, narrative, translation, devotion, and political lampoon. Gathered here are pieces intended for music and the parlor, long romances in verse, travel-stirred meditations, and sharp interventions in public debate, offering readers a comprehensive view of a poet who linked literary art to living voice and civic feeling.

The contents span multiple poetic kinds and text types. There are lyric songs and ballads shaped for existing airs; classical adaptations and translations from Greek and Latin; odes, epigrams, and occasional verses; devotional pieces composed as sacred songs; narrative and descriptive poems in extended cantos; travel rhymes; verse epistles and humorous squibs; dramatic addresses and fragments; and a melologue combining recitation with musical interludes. The collection also retains Moore’s prefaces, advertisements, stage or orchestral directions, and other paratexts, illuminating the intended occasions and media for performance and reading. Together these materials show Moore writing for print, voice, and stage, across private, public, and political spheres.

The architecture of the volume reflects Moore’s movement through distinct yet interconnected projects. Early classical studies and juvenile exercises lead into his large song-cycles for national and sacred settings, while narrative works explore imagined geographies and moral fables. A body of poems inspired by travel and residence abroad broadens his compass, and a sustained satirical register addresses contemporary public life in letters-in-verse, parodies, and political fables. Dramatic scenes, glees, and performance pieces reveal his ear for the theater and assembly room. Read sequentially, these groupings mark changes in subject and tone while reiterating his consistent interest in music, memory, and the social circulation of verse.

Unifying themes run through this variety. Music operates not only as accompaniment but as metaphor for feeling, history, and communal identity. Love—ardent, playful, elegiac—provides a lyric center, often entwined with reflections on fidelity, loss, and time. National sentiment appears as remembrance and aspiration, balancing pride in tradition with calls for dignity and reform. Classical and cosmopolitan frames allow Moore to juxtapose antiquity and modern politics, turning translation into dialogue across ages. Travel expands his horizon without abandoning a core attachment to home. Throughout, the poet regards language as a living instrument: to console, to delight, and, when needed, to admonish.

Stylistically, Moore is distinguished by melodic cadence, stanzaic finesse, and clarity of sentiment shaped for the ear. Many lyrics are built on balanced phrases and recurring turns that recall refrains, inviting memory and song. His narratives favor luminous description and swift transitions, while his satires depend on nimble rhymes, topical wit, and deft shifts of persona. Classical pieces display a tactful blend of faithfulness and free adaptation, domesticated into English music without losing learned grace. Performance texts reveal practical craft—stageable rhythms, cues, and tonal contrasts. Across modes, he prizes accessibility without surrendering artifice, uniting polish with direct emotional address.

Taken together, these works remain significant for the way they fuse literature, music, and public discourse. Moore advanced the tradition of lyric designed for existing airs, giving printed poetry a second life in the voice. He modeled how national feeling can be articulated through art without rancor, and how satire can bite while preserving urbanity. His cosmopolitan engagements—classical, Mediterranean, transatlantic—show a writer mediating among cultures, forms, and audiences. The collection also documents the interplay between private song and civic argument in nineteenth-century letters, making it valuable to readers of poetry, cultural history, and the history of performance.

Readers may approach these pages along multiple paths: by following the evolution from youthful exercises to mature cycles; by reading across themes of love, nation, and faith; or by tracing Moore’s alternating voices—minstrel, traveler, fabulist, and satirist. The presence of prefaces and performance notes helps situate each work’s intended sound and occasion. Together they frame a writer attuned to the social life of verse, at home in intimacy and in public contention. This complete gathering aims to preserve that versatility and to make audible the continuity beneath it: a belief that song, in many registers, can carry memory, argument, and delight.

Historical Context

Thomas Moore (1779–1852) came of age in Dublin amid the aftershocks of the 1798 Rebellion and the Act of Union (effective 1801), conditions that framed the political and cultural horizons of his entire career. Educated at Trinity College Dublin (1795–1799), he absorbed both classical training and the nationalist ferment that touched contemporaries such as Robert Emmet (executed, 1803). This dual formation—classical poetics and Irish patriot memory—shaped his translations, songs, and satires alike. The quest to dignify Irish history and feeling, and to reconcile it with metropolitan polish, underlies his later Irish Melodies, much of his political verse, and his recurrent recourse to antique and legendary matter as vehicles for contemporary meaning.

Relocating to London in 1799 under the patronage of Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Earl of Moira, Moore entered Regency literary society and the world of salons and drawing-room song. His Odes of Anacreon (1800) and the playful Poems by Thomas Little (1801) aligned him with the era’s neoclassical taste for Anacreontic lightness, gallantry, and song, while hinting at a capacity for moral and political edge. The prince’s circle, the theatre, and publishers’ networks made him a fashionable performer-poet who sang his verses to the piano. This milieu fostered the blend of melody, classical reference, and social wit that pervades his translations, early lyrics, and much of his occasional verse.

Imperial service drew Moore across the Atlantic in 1803, when he was appointed Registrar of the Admiralty Prize Court at Bermuda. He soon left a deputy in post and travelled through the United States and Canada (1804–1806), visiting Philadelphia, New York, and the northern waterways to sites like the Cohoes Falls. Encounters with the new republic, slavery, indigenous presence, and Anglo-American tensions inform Poems Relating to America and various songs and descriptive pieces. On returning to Britain in 1806, a notorious (and abortive) duel with Francis Jeffrey over a hostile review signaled his entry into a transatlantic world of print, opinion, and reputation that continued to shape his subjects and tones.

The Irish Melodies (issued between 1808 and 1834) answered a post-Union hunger for cultural self-definition. Working chiefly with the Dublin and London music-publishing brothers James and William Power, and with arrangers like Sir John Stevenson and later Henry R. Bishop, Moore supplied new words to old airs drawn from antiquarian efforts such as Edward Bunting’s collections. The cycle merged national sentiment, domestic music-making, and polished lyric into a repertoire for parlour and concert. Written during the Napoleonic Wars and the long campaign for Catholic Emancipation (achieved 1829), these songs—The Minstrel Boy, The Harp That Once Through Tara’s Halls, and many others—project an idealized, elegiac Ireland to both Irish and British publics.

Moore’s long narratives and lyrics of the 1810s–1820s reflect Romantic Orientalism and cosmopolitan classicism. Lalla Rookh (1817), set among Persian and Mughal scenes, answered a fashionable fascination fed by the East India Company’s ascendancy and figures like Sir William Jones. The Loves of the Angels (1823) mined apocryphal lore, testing religious sentiment and sensual allegory. The Epicurean (1827), a late-Roman Egyptian tale, combined Hellenistic philosophy with exotic spectacle. Evenings in Greece (mid-1820s) resonated with European philhellenism during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830). Throughout, Moore merges travel-library learning, musical interludes, and romance-plot frameworks to explore freedom, faith, and desire within imperial and antiquarian frames familiar to Regency readers.

His political verse tracks Britain’s passage from the Regency through the Reform era. Corruption and Intolerance (1808) and The Sceptic (1809) launched a Whig-liberal attack on repression and philistinism. The Twopenny Post-Bag (1813) skewered the Prince Regent, Spencer Perceval’s successors, and ministers like Castlereagh through fictive “intercepted letters,” a method Moore reused in later lampoons. The Fudge Family in Paris (1818) and Fables for the Holy Alliance (1823) satirized Restoration Europe’s police-state diplomacy, while The Fudges in England (1835) surveyed Reform and Catholic Emancipation (1829) from home. Across these works, verse epistle, parody, and song provide a mobile instrument for topical critique that complements the elegiac nationalism of the Melodies.

Music was Moore’s medium as much as his subject. The Melologue upon National Music and companion projects like National Airs (from 1818) and Sacred Songs capitalized on the sheet-music boom and the drawing room as a political-cultural stage. Issued through the Power brothers, these series paired cosmopolitan tunes—Spanish, Italian, Russian, Swiss—with English lyrics, aligning Moore with a Europe-wide vogue for “national” melody cultivated by collectors and arrangers (a fashion that also drew major composers). His practice bridged antiquarian recovery and commercial modernity: songs circulated as parlour prints, concert pieces, and reading texts. This interart poetics—voice, pianoforte, page—binds otherwise disparate love lyrics, translations, and patriotic verse into a coherent career.

From 1817 Moore lived at Sloperton Cottage, Wiltshire, at the centre of a Whig-literary network that included Samuel Rogers, Lord Holland, and, crucially, Lord Byron, whose Letters and Journals he edited with a celebrated biography (1830). His Sheridan life (1825) and social diaries extend the satirist-lyricist’s public role into historian of reputation and conversation. Financial strains, suits from his Bermuda deputy’s defalcations, and the changing taste of the 1830s–1840s narrowed his late output, though political and occasional verse continued. Moore’s death in 1852 closed a career that had fused Irish nationalism, classical and Oriental romance, and salon song, shaping nineteenth-century ideas of “national music” and Ireland’s image at home and abroad.

Synopsis (Selection)

ODES OF ANACREON (including 'To' and 'Remarks on Anacreon')

Moore’s elegant Englishing of the Greek poet’s odes, celebrating wine, love, and song with playful grace; accompanied by an introductory address and brief scholarly remarks on Anacreon’s text and spirit.

ODES OF ANACREON (Odes I–LXXVIII)

A sequence of lyric miniatures—drinking songs, love addresses, and hymns to the lyre—that distill Anacreontic hedonism into polished, singable English.

SONGS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY

Short translations of Greek epigrams and songs, blending tenderness, wit, and pathos in compact lyric forms.

JUVENILE POEMS (including College Fragments and early Anacreontics)

Early love-lyrics, occasional pieces, and playful classical imitations that showcase Moore’s budding musicality and social wit.

POEMS RELATING TO AMERICA

Travel and occasional verses from Moore’s North American sojourn, mixing picturesque nature sketches and river songs with light political and social observation.

IRISH MELODIES (with Preface)

Lyrics set to traditional Irish airs that interweave love, patriotism, and elegy, giving voice to Ireland’s history and sentiment through memorable song.

NATIONAL AIRS (with Advertisement)

Original words fitted to tunes from many nations, exploring themes of love, memory, and homeland while highlighting the character of each melody.

SACRED SONGS

Devotional and biblical-themed lyrics designed for song, balancing intimate piety with lofty imagery and accessible moral reflection.

A MELOLOGUE UPON NATIONAL MUSIC (with musical interludes)

A staged celebration of national airs that argues for music’s power over memory and identity, illustrated through brief narratives and performed tunes.

SET OF GLEES (e.g., The Meeting of the Ships, Hip, Hip, Hurra!)

Part-songs for convivial and dramatic occasions—maritime partings, toasts, and night-watches—crafted for choral performance.

LEGENDARY BALLADS

Romantic narrative poems that recast classical and folkloric tales (e.g., Cupid and Psyche, Hero and Leander) as swift, lyrical story-ballads of love and fate.

BALLADS, SONGS, ETC.

A large miscellany of love-songs, occasional verses, and character pieces—light in touch and melodic in cadence—suited to salon and stage.

UNPUBLISHED SONGS

A small cache of lyrical love-pieces and epigrams preserved outside earlier collections, intimate in tone and songlike in structure.

A SELECTION FROM THE SONGS IN

Stand-alone numbers taken from Moore’s theatrical and entertainment pieces (e.g., glees and stage songs), emphasizing catchy refrains and scene-setting.

MISCELLANEOUS POEMS

Epistles, epigrams, translations, and occasional verses on friendship, art, politics, and taste, showcasing Moore’s versatility beyond song.

POEMS FROM THE EPICUREAN

Embedded lyrics from Moore’s Alexandrian romance, evoking Nile landscapes, mystic rites, and sensuous banquets in highly pictorial verse.

THE SUMMER FÊTE (with Dedication)

A polished society panorama of a grand outdoor fête that shifts from spectacle and flirtation to reflections on taste, fashion, and ephemerality.

EVENINGS IN GREECE

A musical entertainment in two evenings—interweaving dialogues and songs—to celebrate Hellenic culture, domestic sentiment, and the spirit of liberty.

ALCIPHRON: A FRAGMENT (Letters I–IV)

An unfinished epistolary romance set in the ancient Greek world, sketching a philosopher-lover’s quest amid scenes of art, love, and belief that prefigure The Epicurean.

LALLA ROOKH (with Dedication)

An oriental verse-romance framed by a princess’s journey, containing four richly imaged tales of love, faith, and rebellion that converge on a final revelation.

THE LOVES OF THE ANGELS (with Preface)

A visionary poem in which three angels recount earthly loves and lapses, using their stories to meditate on desire, fallibility, and divine mercy.

RHYMES ON THE ROAD (with Introductory Rhymes and Extracts)

A travel-journal in verse from the Continent that mixes picturesque observation with playful satire on manners, letters, and politics.

CORRUPTION (with Preface)

A political poem condemning patronage and moral decay in public life, urging civic virtue over self-interest.

INTOLERANCE

A companion denunciation of religious bigotry and coercion, advocating liberty of conscience and humane governance.

THE SCEPTIC (with Preface)

A reflective argument for heartfelt, practical faith over cold dogmatism and fashionable unbelief, appealing to moral sentiment and experience.

TWOPENNY POST-BAG (with Preface)

A series of mock ‘intercepted’ letters lampooning Regency figures and policies, using epistolary wit to puncture courtly pretension and ministerial folly.

SATIRICAL AND HUMOROUS POEMS

Short squibs, parodies, epigrams, and occasional pieces on topical fashions and politics, turning contemporary incidents into brisk verse-jests.

POLITICAL AND SATIRICAL POEMS

Longer interventions on public events and figures—elegies, addresses, and dialogic satires—balancing indignation, irony, and theatricality.

FABLES FOR THE HOLY ALLIANCE (with Preface)

Allegorical beast-fables aimed at reactionary post-Napoleonic rulers, arguing—through moral parable—for liberty and against despotism.

THE FUDGE FAMILY IN PARIS (with Preface)

A comic-epistolary travel satire in verse, following a British family in postwar Paris whose letters expose snobbery, credulity, and political cant.

THE FUDGES IN ENGLAND (with Preface)

The Fudge clan returns to lampoon domestic politics and society at home, with each correspondent’s voice caricaturing a different contemporary type.

The Complete Poems of Sir Thomas Moore

ODES OF ANACREON

(1800).

TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH VERSE.

WITH NOTES.

TO

HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS

THE PRINCE OF WALES.

SIR—In allowing me to dedicate this Work to Your Royal Highness, you have conferred upon me an honor which I feel very sensibly: and I have only to regret that the pages which you have thus distinguished are not more deserving of such illustrious patronage.

Believe me, SIR, With every sentiment of respect, Your Royal Highness's Very grateful and devoted Servant,

THOMAS MOORE.

REMARKS ON ANACREON

There is but little known, with certainty of the life of Anacreon. Chamaeleon Heracleotes, who wrote upon the subject, has been lost in the general wreck of ancient literature. The editors of the poet have collected the few trifling anecdotes which are scattered through the extant authors of antiquity, and, supplying the deficiency of materials by fictions of their own imagination, have arranged what they call a life of Anacreon. These specious fabrications are intended to indulge that interest which we naturally feel in the biography of illustrious men; but it is rather a dangerous kind of illusion, as it confounds the limits of history and romance, and is too often supported by unfaithful citation.

Our poet was born in the city of Teos, in the delicious region of Ionia, and the time of his birth appears to have been in the sixth century before Christ. He flourished at that remarkable period when, under the polished tyrants Hipparchus and Polycrates, Athens and Samos were become the rival asylums of genius. There is nothing certain known about his family; and those who pretend to discover in Plato that he was a descendant of the monarch Codrus, show much more of zeal than of either accuracy or judgment.

The disposition and talents of Anacreon recommended him to the monarch of Samos, and he was formed to be the friend of such a prince as Polycrates. Susceptible only to the pleasures, he felt not the corruptions, of the court; and while Pythagoras fled from the tyrant, Anacreon was celebrating his praises oh the lyre. We are told, too, by Maximus Tyrius, that, by the influence of his amatory songs, he softened the mind of Polycrates into a spirit of benevolence towards his subjects.

The amours of the poet, and the rivalship of the tyrant, I shall pass over in silence; and there are few, I presume, who will regret the omission of most of those anecdotes, which the industry of some editors has not only promulged, but discussed. Whatever is repugnant to modesty and virtue is considered, in ethical science, by a supposition very favorable to humanity, as impossible; and this amiable persuasion should be much more strongly entertained where the transgression wars with nature as well as virtue. But why are we not allowed to indulge in the presumption? Why are we officiously reminded that there have been really such instances of depravity?

Hipparchus, who now maintained at Athens the power which his father Pisistratus had usurped, was one of those princes who may be said to have polished the fetters of their subjects. He was the first, according to Plato, who edited the poems of Homer, and commanded them to be sung by the rhapsodists at the celebration of the Panathenaea. From his court, which was a sort of galaxy of genius, Anacreon could not long be absent. Hipparchus sent a barge for him; the poet readily embraced the invitation, and the Muses and the Loves were wafted with him to Athens.

The manner of Anacreon's death was singular. We are told that in the eighty-fifth year of his age he was choked by a grape-stone; and however we may smile at their enthusiastic partiality who see in this easy and characteristic death a peculiar indulgence of Heaven, we cannot help admiring that his fate should have been so emblematic of his disposition. Caelius Calcagninus alludes to this catastrophe in the following epitaph on our poet:—

Those lips, then, hallowed sage, which poured along A music sweet as any cygnet's song, The grape hath closed for ever! Here let the ivy kiss the poet's tomb, Here let the rose he loved with laurels bloom, In bands that ne'er shall sever. But far be thou, oh! far, unholy vine, By whom the favorite minstrel of the Nine Lost his sweet vital breath; Thy God himself now blushes to confess, Once hallowed vine! he feels he loves thee less, Since poor Anacreon's death.

It has been supposed by some writers that Anacreon and Sappho were contemporaries; and the very thought of an intercourse between persons so congenial, both in warmth of passion and delicacy of genius, gives such play to the imagination that the mind loves to indulge in it. But the vision dissolves before historical truth; and Chamaeleon, and Hermesianax, who are the source of the supposition, are considered as having merely indulged in a poetical anachronism.

To infer the moral dispositions of a poet from the tone of sentiment which pervades his works, is sometimes a very fallacious analogy; but the soul of Anacreon speaks so unequivocally through his odes, that we may safely consult them as the faithful mirrors of his heart. We find him there the elegant voluptuary, diffusing the seductive charm of sentiment over passions and propensities at which rigid morality must frown. His heart, devoted to indolence, seems to have thought that there is wealth enough in happiness, but seldom happiness in mere wealth. The cheerfulness, indeed, with which he brightens his old age is interesting and endearing; like his own rose, he is fragrant even in decay. But the most peculiar feature of his mind is that love of simplicity, which be attributes to himself so feelingly, and which breathes characteristically throughout all that he has sung. In truth, if we omit those few vices in our estimate which religion, at that time, not only connived at, but consecrated, we shall be inclined to say that the disposition of our poet was amiable; that his morality was relaxed, but not abandoned; and that Virtue, with her zone loosened, may be an apt emblem of the character of Anacreon.

Of his person and physiognomy, time has preserved such uncertain memorials, that it were better, perhaps, to leave the pencil to fancy; and few can read the Odes of Anacreon without imaging to themselves the form of the animated old bard, crowned with roses, and singing cheerfully to his lyre.

After the very enthusiastic eulogiums bestowed both by ancients and moderns upon the poems of Anacreon, we need not be diffident in expressing our raptures at their beauty, nor hesitate to pronounce them the most polished remains of antiquity. They are indeed, all beauty, all enchantment. He steals us so insensibly along with him, that we sympathize even in his excesses. In his amatory odes there is a delicacy of compliment not to be found in any other ancient poet. Love at that period was rather an unrefined emotion; and the intercourse of the sexes was animated more by passion than by sentiment. They knew not those little tendernesses which form the spiritual part of affection; their expression of feeling was therefore rude and unvaried, and the poetry of love deprived it of its most captivating graces. Anacreon, however, attained some ideas of this purer gallantry; and the same delicacy of mind which led him to this refinement, prevented him also from yielding to the freedom of language which has sullied the pages of all the other poets. His descriptions are warm; but the warmth is in the ideas, not the words. He is sportive without being wanton, and ardent without being licentious. His poetic invention is always most brilliantly displayed in those allegorical fictions which so many have endeavored to imitate, though all have confessed them to be inimitable. Simplicity is the distinguishing feature of these odes, and they interest by their innocence, as much as they fascinate by their beauty. They may be said, indeed, to be the very infants of the Muses, and to lisp in numbers.

I shall not be accused of enthusiastic partiality by those who have read and felt the original; but to others, I am conscious, this should not be the language of a translator, whose faint reflection of such beauties can but ill justify his admiration of them.

In the age of Anacreon music and poetry were inseparable. These kindred talents were for a long time associated, and the poet always sung his own compositions to the lyre. It is probable that they were not set to any regular air, but rather a kind of musical recitation, which was varied according to the fancy and feelings of the moment. The poems of Anacreon were sung at banquets as late as the time of Aulus Gellius, who tells us that he heard one of the odes performed at a birthday entertainment.

The singular beauty of our poet's style and the apparent facility, perhaps, of his metre have attracted, as I have already remarked, a crowd of imitators. Some of these have succeeded with wonderful felicity, as may be discerned in the few odes which are attributed to writers of a later period. But none of his emulators have been half so dangerous to his fame as those Greek ecclesiastics of the early ages, who, being conscious of their own inferiority to their great prototypes, determined on removing all possibility of comparison, and, under a semblance of moral zeal, deprived the world of some of the most exquisite treasures of ancient times. The works of Sappho and Alcaeus were among those flowers of Grecian literature which thus fell beneath the rude hand of ecclesiastical presumption. It is true they pretended that this sacrifice of genius was hallowed by the interests of religion, but I have already assigned the most probable motive; and if Gregorius Nazianzenus had not written Anacreontics, we might now perhaps have the works of the Teian unmutilated, and be empowered to say exultingly with Horace,

Nec si quid olim lusit Anacreon delevit aetas.

The zeal by which these bishops professed to be actuated gave birth more innocently, indeed, to an absurd species of parody, as repugnant to piety as it is to taste, where the poet of voluptuousness was made a preacher of the gospel, and his muse, like the Venus in armor at Lacedaemon, was arrayed in all the severities of priestly instruction. Such was the "Anacreon Recantatus," by Carolus de Aquino, a Jesuit, published 1701, which consisted of a series of palinodes to the several songs of our poet. Such, too, was the Christian Anacreon of Patrignanus, another Jesuit, who preposterously transferred to a most sacred subject all that the Graecian poet had dedicated to festivity and love.

His metre has frequently been adopted by the modern Latin poets; and Scaliger, Taubman, Barthius, and others, have shown that it is by no means uncongenial with that language. The Anacreontics of Scaliger, however, scarcely deserve the name; as they glitter all over with conceits, and, though often elegant, are always labored. The beautiful fictions of Angerianus preserve more happily than any others the delicate turn of those allegorical fables, which, passing so frequently through the mediums of version and imitation, have generally lost their finest rays in the transmission. Many of the Italian poets have indulged their fancies upon the subjects; and in the manner of Anacreon, Bernardo Tasso first introduced the metre, which was afterwards polished and enriched by Chabriera and others.

ODES OF ANACREON

ODE I.[1]

I saw the smiling bard of pleasure, The minstrel of the Teian measure; 'Twas in a vision of the night, He beamed upon my wondering sight. I heard his voice, and warmly prest The dear enthusiast to my breast. His tresses wore a silvery dye, But beauty sparkled in his eye; Sparkled in his eyes of fire, Through the mist of soft desire. His lip exhaled, when'er he sighed, The fragrance of the racy tide; And, as with weak and reeling feet He came my cordial kiss to meet, An infant, of the Cyprian band, Guided him on with tender hand. Quick from his glowing brows he drew His braid, of many a wanton hue; I took the wreath, whose inmost twine Breathed of him and blushed with wine. I hung it o'er my thoughtless brow, And ah! I feel its magic now: I feel that even his garland's touch Can make the bosom love too much.

[1] This ode is the first of the series in the Vatican manuscript, which attributes it to no other poet than Anacreon. They who assert that the manuscript imputes it to Basilius, have been mislead. Whether it be the production of Anacreon or not, it has all the features of ancient simplicity, and is a beautiful imitation of the poet's happiest manner.

ODE II.

Give me the harp of epic song, Which Homer's finger thrilled along; But tear away the sanguine string, For war is not the theme I sing. Proclaim the laws of festal right,[1] I'm monarch of the board to-night; And all around shall brim as high, And quaff the tide as deep as I. And when the cluster's mellowing dews Their warm enchanting balm infuse, Our feet shall catch the elastic bound, And reel us through the dance's round. Great Bacchus! we shall sing to thee, In wild but sweet ebriety; Flashing around such sparks of thought, As Bacchus could alone have taught.

Then, give the harp of epic song, Which Homer's finger thrilled along; But tear away the sanguine string, For war is not the theme I sing.

[1] The ancients prescribed certain laws of drinking at their festivals, for an account of which see the commentators. Anacreon here acts the symposiarch, or master of the festival.

ODE III.[1]

Listen to the Muse's lyre, Master of the pencil's fire! Sketched in painting's bold display, Many a city first portray; Many a city, revelling free, Full of loose festivity. Picture then a rosy train, Bacchants straying o'er the plain; Piping, as they roam along, Roundelay or shepherd-song. Paint me next, if painting may Such a theme as this portray, All the earthly heaven of love These delighted mortals prove.

[1] La Fosse has thought proper to lengthen this poem by considerable interpolations of his own, which he thinks are indispensably necessary to the completion of the description.

ODE IV.[1]

Vulcan! hear your glorious task; I did not from your labors ask In gorgeous panoply to shine, For war was ne'er a sport of mine. No—let me have a silver bowl, Where I may cradle all my soul; But mind that, o'er its simple frame No mimic constellations flame; Nor grave upon the swelling side, Orion, scowling o'er the tide.

I care not for the glittering wain, Nor yet the weeping sister train. But let the vine luxuriant roll Its blushing tendrils round the bowl, While many a rose-lipped bacchant maid Is culling clusters in their shade. Let sylvan gods, in antic shapes, Wildly press the gushing grapes, And flights of Loves, in wanton play, Wing through the air their winding way; While Venus, from her arbor green, Looks laughing at the joyous scene, And young Lyaeus by her side Sits, worthy of so bright a bride.

[1] This ode, Aulus Gellius tells us, was performed at an entertainment where he was present.

ODE V.

Sculptor, wouldst thou glad my soul, Grave for me an ample bowl, Worthy to shine in hall or bower, When spring-time brings the reveller's hour. Grave it with themes of chaste design, Fit for a simple board like mine. Display not there the barbarous rites In which religious zeal delights; Nor any tale of tragic fate Which History shudders to relate. No—cull thy fancies from above, Themes of heaven and themes of love. Let Bacchus, Jove's ambrosial boy, Distil the grape in drops of joy, And while he smiles at every tear, Let warm-eyed Venus, dancing near, With spirits of the genial bed, The dewy herbage deftly tread. Let Love be there, without his arms, In timid nakedness of charms; And all the Graces, linked with Love, Stray, laughing, through the shadowy grove; While rosy boys disporting round, In circlets trip the velvet ground. But ah! if there Apollo toys,[1] I tremble for the rosy boys.

[1] An allusion to the fable that Apollo had killed his beloved boy Hyacinth, while playing with him at quoits. "This" (says M. La Fosse) "is assuredly the sense of the text, and it cannot admit of any other."

ODE VI.[1]

As late I sought the spangled bowers, To cull a wreath of matin flowers, Where many an early rose was weeping, I found the urchin Cupid sleeping, I caught the boy, a goblet's tide Was richly mantling by my side, I caught him by his downy wing, And whelmed him in the racy spring. Then drank I down the poisoned bowl, And love now nestles in my soul. Oh, yes, my soul is Cupid's nest, I feel him fluttering in my breast.

[1] This beautiful fiction, which the commentators have attributed to Julian, a royal poet, the Vatican MS. pronounces to be the genuine offspring of Anacreon.

ODE VII.

The women tell me every day That all my bloom has pas past away. "Behold," the pretty wantons cry, "Behold this mirror with a sigh; The locks upon thy brow are few, And like the rest, they're withering too!" Whether decline has thinned my hair, I'm sure I neither know nor care; But this I know, and this I feel As onward to the tomb I steal, That still as death approaches nearer, The joys of life are sweeter, dearer;[1q] And had I but an hour to live, That little hour to bliss I'd give.

ODE VIII.[1]

I care not for the idle state Of Persia's king, the rich, the great. I envy not the monarch's throne, Nor wish the treasured gold my own But oh! be mine the rosy wreath, Its freshness o'er my brow to breathe; Be mine the rich perfumes that flow, To cool and scent my locks of snow. To-day I'll haste to quaff my wine As if to-morrow ne'er would shine; But if to-morrow comes, why then— I'll haste to quaff my wine again. And thus while all our days are bright, Nor time has dimmed their bloomy light, Let us the festal hours beguile With mantling pup and cordial smile; And shed from each new bowl of wine, The richest drop on Bacchus' shrine For death may come, with brow unpleasant, May come, when least we wish him present, And beckon to the Sable shore, And grimly bid us—drink no more!

[1] Baxter conjectures that this was written upon the occasion of our poet's returning the money to Polycrates, according to the anecdote in Stobaeus.

ODE IX.

I pray thee, by the gods above, Give me the mighty bowl I love, And let me sing, in wild delight, "I will—I will be mad to-night!" Alcmaeon once, as legends tell, Was frenzied by the fiends of hell; Orestes, too, with naked tread, Frantic paced the mountain-head; And why? a murdered mother's shade Haunted them still where'er they strayed. But ne'er could I a murderer be, The grape alone shall bleed for me; Yet can I shout, with wild delight, "I will—I will be mad to-night."

Alcides' self, in days of yore, Imbrued his hands in youthful gore, And brandished, with a maniac joy, The quiver of the expiring boy: And Ajax, with tremendous shield, Infuriate scoured the guiltless field. But I, whose hands no weapon ask, No armor but this joyous flask; The trophy of whose frantic hours Is but a scattered wreath of flowers, Ev'n I can sing, with wild delight, "I will—I will be mad to-night!"

ODE X.[1]

How am I to punish thee, For the wrong thou'st done to me Silly swallow, prating thing— Shall I clip that wheeling wing? Or, as Tereus did, of old,[2] (So the fabled tale is told,) Shall I tear that tongue away, Tongue that uttered such a lay? Ah, how thoughtless hast thou been! Long before the dawn was seen, When a dream came o'er my mind, Picturing her I worship, kind, Just when I was nearly blest, Loud thy matins broke my rest!

[1] This ode is addressed to a swallow.

[2] Modern poetry has conferred the name of Philomel upon the nightingale; but many respectable authorities among the ancients assigned this metamorphose to Progne, and made Philomel the swallow, as Anacreon does here.

ODE XI.[1]

"Tell me, gentle youth, I pray thee, What in purchase shall I pay thee For this little waxen toy, Image of the Paphian boy?" Thus I said, the other day, To a youth who past my way: "Sir," (he answered, and the while Answered all in Doric style,) "Take it, for a trifle take it; 'Twas not I who dared to make it; No, believe me, 'twas not I; Oh, it has cost me many a sigh, And I can no longer keep Little Gods, who murder sleep!" "Here, then, here," (I said with joy,) "Here is silver for the boy: He shall be my bosom guest, Idol of my pious breast!"

Now, young Love, I have thee mine, Warm me with that torch of thine; Make me feel as I have felt, Or thy waxen frame shall melt: I must burn with warm desire, Or thou, my boy—in yonder fire.[2]

[1] It is difficult to preserve with any grace the narrative simplicity of this ode, and the humor of the turn with which it concludes. I feel, indeed, that the translation must appear vapid, if not ludicrous, to an English reader.

[2] From this Longepierre conjectures, that, whatever Anacreon might say, he felt sometimes the inconveniences of old age, and here solicits from the power of Love a warmth which he could no longer expect from Nature.

ODE XII.

They tell how Atys, wild with love, Roams the mount and haunted grove;[1] Cvbele's name he howls around, The gloomy blast returns the sound! Oft too, by Claros' hallowed spring,[2] The votaries of the laurelled king Quaff the inspiring, magic stream, And rave in wild, prophetic dream. But frenzied dreams are not for me, Great Bacchus is my deity! Full of mirth, and full of him, While floating odors round me swim, While mantling bowls are full supplied, And you sit blushing by my side, I will be mad and raving too— Mad, my girl, with love for you!

[1] There are many contradictory stories of the loves of Cybele and Atys. It is certain that he was mutilated, but whether by his own fury, or Cybele's jealousy, is a point upon which authors are not agreed.

[2] This fountain was in a grove, consecrated to Apollo, and situated between Colophon and Lebedos, in Ionia. The god had an oracle there.

ODE XIII.

I will, I will, the conflict's past, And I'll consent to love at last. Cupid has long, with smiling art, Invited me to yield my heart; And I have thought that peace of mind Should not be for a smile resigned; And so repelled the tender lure, And hoped my heart would sleep secure.

But, slighted in his boasted charms, The angry infant flew to arms; He slung his quiver's golden frame, He took his bow; his shafts of flame, And proudly summoned me to yield, Or meet him on the martial field. And what did I unthinking do? I took to arms, undaunted, too; Assumed the corslet, shield, and spear, And, like Pelides, smiled at fear.

Then (hear it, All ye powers above!) I fought with Love! I fought with Love! And now his arrows all were shed, And I had just in terror fled— When, heaving an indignant sigh, To see me thus unwounded fly, And, having now no other dart, He shot himself into my heart![1] My heart—alas the luckless day! Received the God, and died away. Farewell, farewell, my faithless shield! Thy lord at length is forced to yield. Vain, vain, is every outward care, The foe's within, and triumphs there.

[1] Dryden has parodied this thought in the following extravagant lines:———I'm all o'er Love; Nay, I am Love, Love shot, and shot so fast, He shot himself into my breast at last.

ODE XIV.[1]

Count me, on the summer trees, Every leaf that courts the breeze; Count me, on the foamy deep, Every wave that sinks to sleep; Then, when you have numbered these Billowy tides and leafy trees, Count me all the flames I prove, All the gentle nymphs I love. First, of pure Athenian maids Sporting in their olive shades, You may reckon just a score, Nay, I'll grant you fifteen more. In the famed Corinthian grove, Where such countless wantons rove,[2] Chains of beauties may be found, Chains, by which my heart is bound; There, indeed, are nymphs divine, Dangerous to a soul like mine. Many bloom in Lesbos' isle; Many in Ionia smile; Rhodes a pretty swarm can boast; Caria too contains a host. Sum them all—of brown and fair You may count two thousand there. What, you stare? I pray you peace! More I'll find before I cease. Have I told you all my flames, 'Mong the amorous Syrian dames? Have I numbered every one, Glowing under Egypt's sun? Or the nymphs, who blushing sweet Deck the shrine of Love in Crete; Where the God, with festal play, Holds eternal holiday? Still in clusters, still remain Gades' warm, desiring train:[3] Still there lies a myriad more On the sable India's shore; These, and many far removed, All are loving—all are loved!

[1] The poet, in this catalogue of his mistresses, means nothing more, than, by a lively hyperbole, to inform us, that his heart, unfettered by any one object, was warm with devotion towards the sex in general. Cowley is indebted to this ode for the hint of his ballad, called "The Chronicle."

[2] Corinth was very famous for the beauty and number of its courtesans. Venus was the deity principally worshipped by the people, and their constant prayer was, that the gods should increase the number of her worshippers.

[3] The music of the Gaditanian females had all the voluptuous character of their dancing, as appears from Martial.