0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

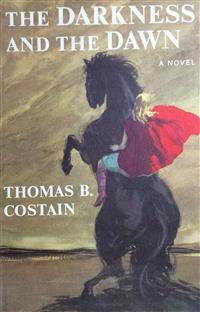

A thrilling tale of suspense centering around a blonde girl and a black horse during the invasion of Europe by Attila the Hun!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Darkness and the Dawn

by Thomas B. Costain

First published in 1959

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

The Darkness and the Dawn

by

Book I

CHAPTER I

1

Of all the myriad dawns which had broken over the dark Wald this one was the most beautiful, because never before had nature been afforded so much assistance. Three mounted figures occupied the crest of the hill: Macio of the Roymarcks, who had been the handsomest man on the plateau in his day, and his two daughters, both of whom were lovely enough to aid the sun in achieving a moment of transcendence. The morning vapors, which the natives called the rawk, had been dispelled and the long grass looked almost blue. The hills behind them were a rich blending of colors, gray and mauve and purple and even a hint of red. The silence was complete, as it should be at such a moment.

The three riders were not concerned, however, with the beauty about them. They sat their horses in a motionless group, gazing fixedly in the direction of the flat meadows to the east.

“I hear them,” exclaimed Laudio, the elder of the two daughters. She was a slender girl, dark and vivid and with the fine eyes of her father.

A faint thud of horses’ hoofs sounded in the distance. Macio nodded his head with its rather noble brow and ran his fingers excitedly through his beard, which was turning white. “As soon as Roric passes that clump of trees,” he said, “he will give Harthager his head. And then we will be able to judge.”

“I see them!” cried Ildico, the younger daughter. Her voice was a light and pleasant treble. Occasionally the dark race which peopled the plateau produced a phenomenon, a daughter with hair like the sun and eyes like the vibrant blue of Lake Balaton at midday. Ildico was one of these. Laudio would rank as a beauty anywhere; save in the company of her younger sister, where she went unnoticed.

After a few moments of intense concentration, Macio sighed with deep content. “We may put our doubts aside,” he said. “Look at the action! He has much of strength and will. I am almost ready to declare that this morning we shall crown a new king of the Roymarck line.”

“Ah, Harthy, my sweet Harthy!” breathed Ildico in an ecstatic whisper. The delight she felt caused the tips of her red leather riding shoes to curl up more than even the cobbler had intended.

An interruption occurred at this point. Despite the intensity of Macio’s concern in the performance of the two-year-old Harthager, he turned to look in the opposite direction. A second horseman was approaching them, riding at an easy gallop. The head of the family looked back at his daughters with a disturbed and angry air.

“Who can this be, spying on us?” he asked. “I decided to start the test before dawn so that no one would be around. If we have ever had a secret which needs keeping, this is the time. I don’t want anyone to know yet how fast the black is.”

“Can we signal Roric to stop?” asked Ildico.

“It’s too late to do anything.”

Roric was already riding across the flatlands at a speed which seemed to increase with each stride. Harthager, a black thunderbolt, was in his full stride. Macio looked at a strange device he carried in the palm of one hand which might have been called the rude forefather of the sandglass. He whistled shrilly. “I can hardly believe it!” he exclaimed.

“It’s Ranno of the Finninalders,” said Laudio, who had continued to watch the leisurely approach of the other horseman. “I thought it might be and now I recognize the feather in his cap.”

“Young Ranno!” cried her father. “I would rather share our secret with anyone else on the plateau than young Ranno. What brings him here at this hour? How did he know we were going to have the test this morning?” A flush of irritation had spread over his handsome features. “Someone must have given it away.”

“You are wrong if you think I did,” said Laudio. “But I don’t see why you are so upset about his coming. He can’t do us any harm.”

“You think not? It’s not only our chance in the races which is at stake. Don’t you realize that we are under the thumb of a man who claims everything for himself? If Attila gets wind of the speed of this youngster, he won’t wait to take him off our hands.”

“Ranno is honorable!” cried Laudio, indignantly.

“Honor does not count when it comes to horses. I have learned that through bitter experience.” Macio looked suspiciously at his dark-haired daughter. “Are you sure you did not invite him?”

Laudio stared at him defiantly. “Why do you always suspect me? I have already said I had nothing to do with it. But I am glad he has come. He is paying us a neighborly visit. That’s all.”

She tapped the flank of her mount with the blue leather of her heel and rode off to meet the visitor. Although she had neither saddle nor bridle, she sat her horse with ease and mastery. It was the proud custom of the people of the plateau to ride bareback and there was not a single bit of equipment among the five of them, Macio and his two lovely daughters, his son on Harthager, and the visitor riding in from the south.

The pounding of the black’s hoofs was now like thunder from the hills. Macio looked again at the device in his hand. “It passes all belief. It is a miracle.” He scowled back over his shoulder. “What a bad stroke of luck that he is here! He always looks after his own interests. They have always been that way, the Finninalders. Do you think this is just a friendly call, Ildico? At this hour of the morning? Mark my words, young Ranno has heard something.”

“Do you think you should express doubts of him before Laudio?” The younger daughter looked unhappy over the situation which had developed. “I am afraid you have hurt her feelings badly.”

“I am upset myself.”

Harthager was nearing the end of his run and Macio did not raise his eyes from the device. “Another hundred yards and we will know!” he said, in a tense whisper.

“Will it be a new record?” asked the younger daughter, excitedly.

“I can’t be sure yet. But I think so. Yes, yes! It is certain now. He will be well ahead.”

Ildico clapped her hands exultantly. “Harthager the Third!” she said.

“Yes, Harthager the Third.”

Using only his knees, Roric checked the speed of the black two-year-old and brought him up the slope of the hill to reach a standstill in front of them. He nodded his head at his young sister and grinned broadly.

“How did you like that?” he asked. He was a taller copy of Laudio, slender and handsome and with a poetic darkness about him. “Didn’t I predict we would win everything this spring at the Trumping of the Baws? That is exactly what we are going to do.” Then he turned to face his father and his manner became anxious and solicitous. “Well? Was the time good, Father? Good enough?”

Macio leaned over his horse’s neck to pat his son’s shoulder. “Yes, my boy. The time was better than good. It was remarkable.”

Roric smiled eagerly. “I thought it was. But I could not be sure.”

“I began the count when you turned that clump of trees. There can be no doubt about it. He was well ahead of the record. I was particularly careful because I did not want to deceive myself.”

The three exchanged smiles of delight over the result of the test. “I knew he could do it,” said Roric. “In spite of what Brynno says, I didn’t find him hard to ride, Father.”

“Of course not!” cried Ildico, indignantly. “He’s as gentle as a lamb.”

Macio turned sharply in the direction of his golden-haired daughter. “Have you been disobeying me?”

The girl shook her head. “No, Father. But it has been a great temptation. You haven’t been fair to me. Because I am a girl, you tell me I mustn’t ride him. But he likes me. I think he likes me better than anyone. As soon as he sees me, he neighs and comes running to me. I am sure I would find him gentle.”

Her father snorted indignantly. “You will never find out because you are not to try. If you show any tendency to disobey me, I shall have you locked up.” His voice took on an appealing tone. “Ildico, my beloved daughter, can you not see how dangerous it is?”

Laudio and the visitor had reached the crest of the hill by this time. Ranno of the Finninalders tossed one long and muscular leg over the neck of his horse and dropped to the ground. He had arrayed himself in considerable grandeur for this early morning visit: a tall peacock feather in his cap, a riding tunic of a lustrous green, wide trousers of yellow, a belt of gold coins so heavy that they clanked as he moved, shoes of green fretted leather, each fret stamped with the tree and raven of the Finninalders. Roric, who disliked this young neighbor, said to himself: “He has the look of a suitor in his eye. Which of my sisters does he come courting?”

“I offer you my most humble respects, Macio of the Roymarcks,” said Ranno, bowing to the head of the family. He then turned to the younger daughter. “And to you, Ildico. You are looking more lovely than ever.”

“We bid you welcome,” said Macio. “But you come at a very early hour.”

“I have had no sleep. Some visitors arrived last night from—from a point not far east. We talked through half of the night about what we may expect since a certain man of great power has planted his sword in the ground again. I then took horse and rode over, feeling that you would be interested in what they told me.” He nodded his head and smiled. “It was a fortunate time I selected for my arrival. I have seen something this morning the equal of which I may never see again as long as I live.”

The black was showing impatience at the inactivity in which he was being held. Macio leaned over and laid a reassuring hand on his moist withers. He then looked at his visitor. “You think well of him?”

“I thought I had a promising lot this spring,” answered Ranno. “But having seen this one perform, I am out of conceit with all of mine. Did you make a count of his time?”

Macio nodded in assent. With a slight pressure of his knee, he brought his mount around until he faced the east. He raised one hand in the air.

“Listen to me, all of you,” he said, with an almost fanatical gleam in his eye. “You, Roric, my son. And you, my two daughters. And you also, Ranno of the Finninalders, son of my old friend, who has happened to be here on this great occasion.

“You may think,” he went on, “that I am making too much of what has happened before our eyes this morning. But I must say what is in my mind. It is known to all of you that the records of our race have been preserved only by word of mouth. That is why we have so little certain knowledge of our beginnings. We know that we come from the very far east, that at one time we lived within sight of the Snowy Mountains and that we migrated with the seasons. We have always been breeders of fine horses. Even in the days when we held out our arms to the Snowy Mountains on rising, it was so. We strove always to improve the breed. When we were forced to leave our ancestral grounds—for reasons long forgotten—and moved to the west, it was so. When we passed the Valleys of the Korama, of the Upper Volga, of the Urals, it was still so. The breed grew stronger when we sojourned in Sarmatia and later when we settled for many generations in Illyricum. Now we have lived for centuries on this fruitful plateau. We are few in numbers and so we could not hold out against the might of Rome. Today we are a part of the empire of Attila. In spite of our political misfortunes, we have never ceased to strive for supremacy in the breeding of horses.”

He paused and looked in turn at each of his listeners. “This morning we have accomplished at last what we have striven for so long: the goal of our ancestors, even when they were harried westward and left their footmarks in unfamiliar sands. I declare to you, after an accurate count of the time, that we have raised in Harthager the fastest horse the world has ever seen.”

There was a moment of silence and he then turned to young Ranno. “We have had the honor of raising him and we are proud of it. But in the end he will belong to our people and not to us. And that means, young Ranno, that the secret must be kept close. We do not want him taken away from us. That is what will happen if a whisper of today’s test gets out.”

The representative of the Finninalders bowed soberly. “You can depend on me to say nothing of what I have seen,” he said.

2

What followed was in keeping with certain customs which had been developed over the years in the family of the Roymarcks. Ildico, as the youngest, took the lead. Her hair, showing a slightly reddish tinge under the warm morning sun, streamed out behind her as she set her horse to a triumphant caracoling. Her father had dismounted and walked proudly at the black’s head.

“Stand back!” Ildico cried to the handlers and field workers who came running out as soon as they arrived in sight of the horse sheds. “No one is to go in yet except Justo, who will heat the water.”

The overseer, who was withered with age, asked in a quaver, “Then we have a new king, Lady Ildico?”

She gave a proud nod and her eyes beamed at him. “Yes, Brynno.” Her voice was high-pitched with excitement. “A new king indeed! A great king, an emperor! The fastest we have ever had. My father says he is the fastest of all time. Tell Justo to hurry.”

By the time they reached the sheds Justo had placed red-hot stones in the water trough and it was hissing furiously and sending up clouds of steam. Not knowing the custom, Ranno followed the members of the family inside and was unceremoniously ushered out by Ildico.

“I am sorry,” she said, giving his arm a shove. “This is for Roymarcks only. Finninalders stay outside.” Then she laughed. “It’s what we have always done. No one else is allowed to touch the horse or to watch.”

Roric and the two sisters dipped pieces of soft cloth (for nothing rough must touch the hide of the new king) in the warm water and proceeded to give the black a rubdown which could only be described as reverent. They hummed an air as they worked, a monotone which repeated itself over and over, with curious quirks and twists. The head of the family intoned words to the air. It might have seemed that he was telling of the great deeds of the Roymarcks but instead he was reciting the story of the fine horses they had raised. He told of a powerful black on which an emperor of Cathay had ridden (until he became frightened and fell off), of a gallant roan which had carried his master across all of Sarmatia in three days, of Harthager the First and a mad gallop he made to Vindobona (which later became a famous city named Vienna) without a single pause to take the word of Roman legions approaching, and who had died of his efforts. At the finish Macio said, with a hint of moisture in his eyes, “The bones of these kings have moldered away and today a new king stands in their stead.”

When the glossy coat of the new king had been thoroughly rubbed and dried, and he had been patted and made much of, and a lump of saccharum had been secretly conveyed to him on the palm of Ildico’s hand, he was given the smallest kind of a drink of water. Then a basin of oats was placed before him and he began to eat with finicky tremors of his mouth and nostrils.

In the meantime the head of the household had been searching in a chest of extreme age and dilapidation, which looked as though it had originated within sight of the Snowy Mountains also. He emerged with a jeweled headpiece and a pair of ancient combs. While he adjusted the headpiece, his two daughters employed the combs in smoothing out the mane and tiring it with silken tassels.

The toilet of the monarch having been finished, Macio walked to the entrance and threw the door open. He said to the servants who had pressed against it in a state of intense excitement, “You may come in.” Ranno followed them into the shed and, giving Ildico the benefit of a wink, he asked, “May a mere Finninalder enter now?”

Macio walked slowly to the other end of the long, dark shed. He took down a silver chain from a section of the wall where mementos of the past were hanging. It was a handsome thing, heavily studded with opals and turquoises and squares of carnelian and sardonyx, and suspended from it was a silver figure of the Roymarck horse with rubies for eyes.

Harthager seemed to sense what was coming. He ceased eating and raised his head high in the air. The head of the family walked close to him and placed the chain around his neck.

“Harthager the Third,” he said, with as much solemnity as a bishop anointing a king in a great domed cathedral. “May you be worthy of the Roymarck chain which so many of your forefathers have worn. We expect great things of you. We believe you are destined to be remembered—perhaps for all time.”

Then he stepped back and stood in an expectant attitude, listening. The members of his family followed his example, turning their heads toward the door through which they could see a corner of the fenced meadows where all of the Roymarck horses had been collected. There was a long moment of silence. Then from the fields came the single neigh of a horse, a high, triumphant note. Another followed and then, almost instantaneously, the rest joined in.

Macio’s face lost the look of doubt which had been settling over it. He waved an arm in the air. “They know!” he cried. “They know what we have done. And they approve.”

Laudio was smiling delightedly but Ildico gave full rein to her emotions. She did not care that tears began to stream down her cheeks when the black monarch pawed at the ground and trumpeted an answer to his fellows in the fields. She put a hand under her brother’s arm and leaned her yellow head against his shoulder.

“Look at him, Roric!” she whispered. “See how high he holds his head. See the look in his eyes. He knows he’s a king!”

When the excitement had subsided to some extent, Ranno came to Ildico and studied her face with a puzzled frown.

“It’s true,” he said. “You actually were crying. You seem to take this seriously.”

“Of course I take it seriously,” said the girl, turning on him, angrily. “It is the most important thing in the world to us. No, not quite that. It is the second most important thing. And let me tell you this, Ranno, I shall always remember this morning as one of the great moments in my life.”

The visitor shook his head. “Do you look on me as a friend?” he asked. “An old enough friend to be honest with you? I am very much afraid that you are a fraud, my pretty Ildico. Consider for a moment that uproar from the meadows. Do you really believe it was a—a tribute from the rest of the stock? Latobius and Laburas, hearken to me, and all the other gods!”

Ildico looked at him so fiercely that for a moment he thought she was going to spring at him. He even took an involuntary step backward.

“Of course, I believe it!” she said. “Now I will be honest with you. Do you know why you have never been able to raise horses as good as ours? You don’t love them and you don’t understand them. You don’t believe they have strange powers, that they can feel and hear things in the air. It’s true. We believe it, all of us, we know it is true.”

In spite of her earnestness, Ranno continued to regard her with an amused grin. “Have it your way, then,” he said. “I accept the reproof. But I did see that ancient overseer of yours leave the shed before this—this touching ceremony began. Of course we should not be skeptical and say that he was going out to the meadows to be there at just the right time; in other words, to make sure that the uproar began at the exact moment.”

“It is not true!” cried Ildico. “I hate you, Ranno of the Finninalders, for saying such things!”

He grew serious at this point. “No, no, not that, Ildico. I will get down on my knees and beg your pardon. I will accept anything you tell me. But you must not hate me. That I could not bear.”

The ceremony over, the company walked slowly out of the shed. Ildico, beside her father, was aware that the black eyes of Ranno were still fixed on her with a disturbing intentness. She said to herself: “Why doesn’t he look at Laudio? He must not behave this way. There will be nothing but unhappiness for all of us.”

3

It was a time of crisis in the kitchen, which constituted with the long dining hall the largest part of the low red-roofed home of the Roymarcks. The last smoked shoulder of ham hung from an otherwise empty rafter. The casks which had held the salted fish were empty. The supplies of vegetables buried in pits for winter use were exhausted. It was a difficult thing to feed so many mouths on dishes made of crushed grain and on eggs and old hens no longer capable of laying eggs.

Ildico was in the kitchen, discussing what could be done with a rather meager catch of fresh fish from a nearby stream when she was summoned to attend her father. It might have been expected that on the death of their mother the older sister, who seemed most capable in her quiet way, would have assumed charge of the household. Laudio was of a dreamy disposition, however, and not as practical as her beautiful younger sister; and so the largest part of the burden had fallen on the decorative shoulders of Ildico.

“Where is the master, Nateel?” she asked, giving her remarkable hair a quick upward twist and binding it in place with a red ribbon.

“In his room, Lady Ildico.”

The life of the household centered in the dining hall and the kitchen. The rest of the space in the house was given over to tiny cubicles where the members of the family, the servants, and such guests as might be on hand spent the hours of darkness. They were small, dark, and airless, and the furnishings consisted of pallets of straw and pillows (for feminine use only) of feathers. The room of the master, however, boasted a chair, a bed, and a small tapestry on one wall. He was lying stretched out on the bed when his daughter answered his summons.

“Sit down, my Ildico,” he said. “We have things to talk about. I have just said farewell to the young man. He asked me to say that he would have paid his respects to you and Laudio before leaving but that he had a very busy day ahead of him.”

“He seems to be a very practical young man,” remarked Ildico.

“He is indeed. I will come back to that later.” The master of the household seemed unusually grave. “I had a talk with him after breakfast. The news from the Hun court is serious, my child. Attila has decided to make war—against Rome, according to most reports. He is going to raise the largest army the world has ever seen and he will demand from us, from the people of the plateau, all the men and money we can supply.”

Ildico felt a sudden contraction of the heart. “Will Roric have to go?” she asked.

Macio gave a somber nod of affirmation. “I am afraid that he will be expected to command the men we send. A score, in all probability. He must have his baptism of fire sooner or later but it wrings my heart to think of him fighting in such a cause. Some men are saying that the time of the twelfth vulture is over and that now Rome must fall. Perhaps they are right. But must the mastery of the world be yielded into the hands of the Hun?”

There was a long pause and then Ildico sighed. “Will we be expected to supply horses?” When her father nodded his head in affirmation, she said, quickly, “But they won’t take Harthager!”

It might have seemed that the prospect of losing the new king was as distressing as the certainty that the son of the house would lead a company in the fighting. Macio looked thoroughly unhappy. “How can we tell? They may demand from us everything which runs on four legs. Yes, they may take Harthager.”

“Won’t they realize that he represents centuries of careful selection and breeding?”

“I doubt if that will mean anything to Attila. He is more likely to say, ‘What better ending for a fine horse than to carry one of my men into battle?’ I am very much afraid, my child, that we must reconcile ourselves to losing our new king. His reign is going to be a brief one.”

“My poor Roric!” said Ildico, her eyes swimming with tears. Then she added, “My poor Harthager!”

As though this were not enough trouble for one day, Macio proceeded then with another explanation. “I am not sure that this will be a complete surprise to you, my small one,” he said. “You are very observant and I think you are wise as well. My talk with young Ranno was not limited to the matter of Attila’s exactions. He has asked me for your hand in marriage.”

“No, no!” cried Ildico. Her father’s surmise had been correct. She had been more than half expecting some such announcement but this did nothing to lessen the distress she now felt. “It is Laudio he must ask for, not me. It has always been understood he would ask for Laudio.”

“That is true. I discussed the match with old Ranno several times before he died and it was always Laudio then. She was our first daughter and you were no more than a very small and saucy child. But it seems that young Ranno has been thinking it over. It is you he wants. He made that very clear to me this morning.”

“I won’t marry him, Father!” Ildico spoke with a passionate earnestness. “I won’t! He must be brought to his senses. He must be told that he is expected to marry Laudio, that it was so arranged between you and his father.”

Macio was surprised at her vehemence. “But, my child,” he said, “I cannot dictate to the young man and tell him who he should want as a wife. He is a very determined young man and knows exactly what he wants. What are your objections to him as a husband?”

“I don’t like him!” Ildico’s eyes, which ordinarily seemed soft and completely feminine, were now filled with a determination the equal of anything her suitor could have produced. “I have never liked him. I think—I actually think, Father, that I hate him!”

Macio was completely at a loss. He stroked his long beard and frowned as he studied her face. “But why this dislike? He seems to me a handsome man. He is managing his lands as well as his father did. He has ambition as well as ability.”

“And what more could a girl ask?” Ildico indulged in a short and far from amused laugh. Her eyes had turned as cold as blue jewels and the line of her nicely cleft chin had become a study in self-will and determination. “Don’t you know, Father, how generally he is disliked? Roric grew up with him and has always hated him. The son of the Ildeburghs, the boy who was carried off and sold as a slave——”

“And who escaped and is now in the service of Attila,” said her father.

“He was a gentle boy, Nicolan of the Ildeburghs. I liked him very much. They say he has become a splendid soldier. He was the same age as Roric and Ranno of the Finninalders. He and Roric were close friends but they could not get along with Ranno. His servants are afraid of him. Make no mistake about Ranno, Father. If the time should ever come when we are free again, Ranno of the Finninalders would try to take your place as leader of our people.”

“Now you are indulging in wild speculations. How can you tell what ideas the young man has in his head?”

“Look at him. Watch him. You can read his designs in those calculating eyes of his.” Ildico had fallen into a breathlessness of speech in her desire to convince her father. “There is another reason. When that terrible governor was put over us by the Hun——”

When she paused, her father supplied the name. “Vannius?”

“Yes, Vannius. When he seized the Ildeburgh lands and killed the owner, old Ranno came to terms with him and took over the estates. I know you never speak of it but everyone in the plateau knows about it. Everyone knew it was an injustice and he was hated for taking advantage of a friend’s misfortune. Young Ranno has shown no intent to right the wrong. He still holds the Ildeburgh lands.” She got to her feet and looked down at her father with eyes which blazed. “Do you think I would marry him as long as he holds the lands of that unfortunate family?”

Macio rose in his turn. “You must not fret your pretty head, my Ildico,” he said. It was clear he still regarded her as a child and not as a forceful member of the small family circle. “I did not know your feelings were so strong. But I confess I am still puzzled. Does Laudio feel as you do?”

The girl’s face clouded over. After a moment she gave her head a shake. “No, Father,” she answered. “I am very much afraid that Laudio loves him.”

4

Macio was awakened that night by a steady pounding on the gate of the palisade which surrounded the house. He sat up on his bed and listened for a moment. There was not a sound in the house but this did not mean that everyone was sleeping. It was certain that many of the servants had heard and were lying on their pallets in silent terror, their heads tucked under the bed-clothes.

The head of the household, who would have been the head of the little nation of plateau dwellers if they had been strong enough generations before to maintain their independence, had little more stomach for venturing out into the darkness than his people. A stout Christian, he still believed that the night belonged to the Devil, as indeed did all the good priests in the world, all the way up to the great bishop in Rome who was called the pope. When Bustato, the major-domo, had closed all the doors and windows for the night and had bolted them securely on the inside, the master was as willing as the most apprehensive servant or the sulkiest groom to leave the great outdoors to the powers of evil. When the shutters rattled, he was as likely as any of them to say to himself that it was not the wind, that it was the Tailed One, the Flame-spitter, Old Horny (a few of the names they had for the Prince of the Underworld), trying to force his way in.

But there was something insistent about the pounding on the outside gate, a regularity which was human and not to be mistaken for the haphazard efforts of an angry devil to break through barriers before riding off on the wind to find some less careful victim.

Macio got out of his bed. “This must be seen to,” he said. He reached in the dark for a winter robe lined with bearskin and slipped it over his shoulders. Outside the door he picked up a bow and pounded with it on a metal shield hanging on the wall. The sound reverberated through the silent household.

“Get up!” he cried, angrily. “There is someone at our door who seeks entrance.”

The first to answer the summons was Bustato, the major-domo, looking thoroughly frightened.

“I am sure, Master,” he said, “that it is no human hand knocking so loudly. It is the Devil demanding to be let in.”

“I will open the gate myself,” declared Macio. He glanced around him at the other members of the household who were beginning to gather. Their faces were moist with sleep and every bit of hair they possessed was standing on end with fright. “But you will all go with me.”

“Who is it?” he asked, when they reached the gate in the outer palisade.

“It is not the Old One, Macio of the Roymarcks.” The voice on the other side of the gate displayed no impatience at having been kept waiting so long.

“Ah, it is you, Father Simon,” said Macio. He reached for the bar which kept the gate clamped securely in place. “What brings you to our door at such a late hour? Is there trouble?”

“There is always trouble, my son. But I think that on this occasion my motives are mostly selfish.”

The gate swung in and the midnight visitor stepped into the compound with a readiness which demonstrated his desire for some supper and a couch for the balance of the night. It was very dark, there being no stars in the sky, and the low-burning torch, which Macio had taken from a sconce in the dining hall as he came through, gave no clear outline of the visitor’s appearance, save that he was small and attired in a priestly robe. A water bottle was swung over one shoulder and he leaned on a pastoral staff.

“I came afoot,” said the priest. “I thought it the safer way.”

Macio led him into the house. The servants were already scattering with eagerness to finish their sleep. Bustato had closed the gate and was driving the bolt back into place. He struck with great vigor. Fear rode on open gates when night came down and the stars were hidden.

“You are here because of Stecklius,” said Macio, when he and his guest had seated themselves in the hall where no one else could hear.

The priest nodded his head. “It is indeed because of Stecklius. He thinks he will win his way back into the good graces of Attila by making a determined effort to wipe out Christianity here.”

“We have been hearing rumors about it. Has he any conception how many Christians there are on the plateau? You have been a faithful evangel, Father Simon.”

“I doubt if he has a full list. But of that we cannot be sure. It was to warn you that I came. It is quite possible that his first move will be against you and your household.” The priest indulged in a deep sigh. “Stecklius has sent me notice that I am to leave or face the consequences. Well, my good friend Macio, I do not intend to leave the plateau country which I have come to love. I have had such orders before and have paid them no heed. But this time I must go into seclusion, I think.”

“I am happy to receive you in my house, Father Simon,” declared Macio. “You will stay here with me and together we will laugh at Stecklius, that ugliest of all the dwarfs, that thick-skulled Hun.”

“There was a hint in the message I had from the worthy Stecklius,” said the priest, “that I should be wise enough to return to my own people and so cease from causing dissension and trouble in the realm of the great Attila. It is twenty years since I left the island of Britain and, if I returned now, I would find all my old friends and brethren dead or scattered. It is an odd thing that in the blessed island from which I came we cannot sleep at nights for thinking of all the wicked heathen here in the land of the Alamanni and up north where the Norsemen live. It is so easy to see the evil in other people and never recognize it in ourselves. If I went back I would not be content to try my hand at saving the unregenerate among my own people—where they exist in great numbers, I assure you—but I would soon be caught again with the old desire to be about my Master’s work in distant fields. I would come back; and so there is no sense in my going away at all. No, I have lived here so long that I think that now I must remain, even if I have become obnoxious in the sight of Stecklius.”

Ildico made her appearance at this moment, carrying a lighted lamp in her hand. Her hair was very much disheveled from sleep.

“I was told Father Simon had come,” she said, “and so I had to welcome him, without waiting to attire myself properly.”

The priest got to his feet. “I am happy to see you, my daughter. It is a long time since I have been here and our little yellow bird seems to have been growing up in my absence.”

Macio addressed his daughter. “Our good friend has come to stay with us. He will be welcome to remain here as long as he can stand our tendency to think more of the welfare of our horses than the comfort of our guests.”

“For a few days only,” declared the priest, firmly. “As soon as I have made certain necessary arrangements, I shall retire into the sanctuary where I spent so much of my time years ago.”

“The cave in Belden Hill?”

The lamp held by Ildico made it possible for them to see that the priest looked very tired. He nodded his head, which, after the fashion of the earliest missionary orders, was shaven in front.

“It is a dry haven I have on the Belden,” said the priest, “and it is so well hidden away that I can stay there in peace. Do you think I would bring down the wrath of the Attilas and the Steckliuses on my dear friends by settling myself in their midst? No, it is kindly thought but in a very short time I must be on my way. In the meantime I shall be very happy to stay in that little room behind the hearth about which no one but you has any knowledge.”

“And all the servants on the place,” said Ildico.

“You know how little we have to fear from them, Father Simon,” declared Macio. “You will be at least as safe in our dark hideaway as in the cave on Belden.”

“And there is always food here,” said Ildico. “I will see that something is prepared for you at once.”

Through a suspiciously quiet house, the master conducted his nocturnal visitor to his own room. His groping hand found a particular place in the paneling and pressed down firmly on it. There was a sound of creaking and straining and then a section of the wall opened. A small room lay behind. It was large enough to contain a pallet and a narrow table with a pitcher and other domestic articles; and, because it was located between Macio’s apartment and the great hearth in the dining room, it had the advantage of being warm at all times.

The apparatus which moved the paneling was cumbersome and rusty and as easy to detect as the drawstrings in a magician’s cloak. The little priest placed the candle, which Macio had given him, on the table and looked about him with a reminiscent smile.

“This is the fourth time I have been a guest in the hideaway,” he said. “I think it likely that I have been the only one to seek the security it offers.”

“You, and the children when they were small enough to play games of make-believe.”

Ildico entered at this point with a platter of food. The little priest smiled. “Whenever I begin to imagine myself above the weaknesses of the flesh,” he said, “my stomach takes me in hand and shows me my folly. I confess, my daughter, that I am very hungry. I have eaten nothing today save a piece of cheese and a swallow of goat’s milk.” He looked up at her with affectionate approval. “Ah, time is such a disrupter of families! It turns little girls into beautiful women and then tears them away from those who love them. You will not have this daughter of the sun with you much longer, my old friend.”

“Very little longer, I fear,” answered Macio. “I had a reminder of it this morning and have not yet fully recovered from the blow.” He turned to his daughter. “The good father has come a long way and is very weary. We must leave him to his supper, and then the comfort of his couch.”

The next evening, as soon as the sun had vanished from the western sky, Bustato went over the house with two helpers and proceeded to close all the shutters and lock the doors, ending in the dining hall where he fastened the bolts with a particular vigor. Then he set torches alight in iron sconces along the walls and placed lighted candles on the table.

Bustato then drew a bench away from the table and seated himself comfortably in the center. The two helpers placed themselves with equal nonchalance on each side of him.

Almost immediately thereafter the servants began to stream in. A stranger to plateau ways would have been amazed by the number of them. There were cooks and their assistants, chamber women, cellarers and wine drawers, ax and, as well, chimney men, horse trainers, grooms, field hands and workers from the manure pits who very humbly took seats at a distance from everyone else. They all wore the Roymarck livery, a band of blue around the neck of the tunic and the Roymarck horse embroidered on the right sleeve. There were enough of them to make it certain that no one had to work very hard: there were, clearly, three pairs of hands for every job. The ruddy-faced men and the buxom women looked well fed and content.

When Macio came in, followed by the three members of his family, the servants were seated in a solemn semicircle. They did not get up nor did they indulge in any form of greeting. A bench had been kept clear in the center and here the head of the household seated himself with Roric on one side and Laudio on the other. Ildico had changed from the rose-colored riding clothes which she had worn all day into a white pallium which almost reached the floor and allowed no more than an occasional glimpse of her white sandals. She chose to seat herself beside Brynno, the overseer. They carried on a discussion in whispers, her blonde head with a pink ribbon around it nodding earnestly, until the head of the family turned a stern and reproachful face in their direction.

Macio looked about him then and broke the silence officially. “Is everyone here?”

Craning necks uncovered the fact that only old Blurki had not put in an appearance. He was a misshapen, ill-tempered curmudgeon with a sharp tongue in his head who served as jester for the household and further enhanced his value by doing sundry chores about the place. He was responsible for bait for the fishermen, he kept the hearths blazing when once lighted and, if he failed to earn one loud and general laugh during the course of an evening, he would have to stay up to wash and dry all the flagons and drinking mugs and hang them up on nails in a beam across one end of the long room. Whenever this happened he would mutter bitterly over the task about the knuckleheads, the ninny-noodles, the suetguts who did not know a good joke when they heard it.

“I placed him outside as lookout,” said Bustato. To justify his choice, he added, “He always sings off the pitch.”

“Then give the signal,” said Macio.

The man who sat nearest the hearth tapped with his knuckles on the wall. There was the same sound of creaking and straining as the dilapidated machinery proceeded reluctantly to do its work. In a moment Father Simon in his full robes stepped out into the light of the long dining hall and walked slowly to a position in from of the rows of benches. The whole company rose and began to sing a hymn, one of the very early ones which had been falling into disuse as ritual had developed in the services of the Church.

The little priest, singing louder than any of them in a bass voice surprisingly robust in one of his stature, looked about him and felt his heart fill with a deep sense of happiness.

“How firm they are in the faith!” he thought. “I was right to come here and to stay, even in the face of the early discouragements. My poor efforts have been bounteously rewarded. No longer do they worship their Wotan, the All-Father, or Thor the Thunderer. They have lost all belief in Asgard, the city of the Alamanni gods, and all fear of the coming of Ragnarok, the day of dreadful strife. They are Christians and happy in the teachings of the Lord Jesus Christ. Stecklius may harry me from the plateau but he cannot dim the belief and the peace I read in every pair of eyes before me.”

CHAPTER II

1

The Man Who Wanted the World was moody and irritable. In the murky closeness of the partially subterranean room where he worked, sprawling on a bench without a back, he glared at Onegesius, his chief minister and aide.

“You say the last of them, this German prince, has arrived. Why are you sure he is the last?”

It was his custom to demand explanations many times and, if any divergence could be detected from previous versions, he would explode into rage. “Even you—the only one I have trusted—you are now trying to deceive me!” Knowing this, Onegesius proceeded warily with what he had to tell. “Mursa, there are ten of them in my hands now. The German arrived this morning in chains. Our men are watching in all parts of the empire for any further signs of disobedience. But there have been none. The other rulers are showing readiness to meet the full demands you have laid on them for soldiers, horses and money. But be sure of this, O King of Kings: our men have not lost any of their vigilance. They are watching. They see everything, they hear everything. If there is any sign of change, we will know at once.”

They were referring to the heads of states which had been submerged in the conquering advance of the Huns; first under Rugilas and now under the great, the omnipotent, Attila. The ten prisoners were chiefs of Teutonic countries or kings of racial pockets in Scythia or even skiptouchoi, the barons of the Sarmatian people. They had refused to supply Attila with the sinews of war.

For the better part of a year the Scourge of God (a title which Attila accepted with considerable inner satisfaction when it was first applied to him) had been working without cessation on his plans to assemble the largest army the world had ever seen. The strain had not impaired the strength of his thickset body but it had taken toll of his nerves. His eyes had always been sunk deep beneath his bushy brows; and now they gleamed like a wild beast’s in the darkness of its lair or, more nearly perhaps, like fireflies in the eye sockets of a skull.

“They must die!” he cried, in a sudden fury. “There must be no delay in teaching the world a lesson.”

“They have not been tried, Great Tanjou.”

“Their guilt is clear to me. Nothing else matters.”

Onegesius was a man of good address but he was a subordinate by nature and a timeserver by acquired instinct. He had never pitted his ideas or his convictions against those of his master. But on this occasion he was shocked into a hasty word of protest.

“But surely, O Lord of the Earth and the Skies, it would be wise not—to be too hasty. Some of them, as you know, are the heads of powerful states. If their guilt could be established before you took their lives——”

“No!” Attila’s heavy fist fell on the flimsy table at which he sat. “There is no time. In six weeks, in two months at the most, I must have my army ready. I must be prepared to march. To hold a trial and then see that the evidence was used to influence the minds of people would take all of that time. It is a swift lesson they need. A sharp and terrible one. These heads of states who disregarded my orders must pay the price of their treason at once. Then there will be haste to obey me.”

He got to his feet and began to pace up and down. His legs were short in proportion to the rest of his body and the extreme heaviness of his torso made the disparity seem greater. He was in a physical sense a Hun of Huns: his head was as round as a melon, his eyes were small and with an almost porcine suggestion about them, his nose was short and with a slightly comic upturn. He was not in any sense a comic figure, however. There was power, cruel and inexorable, in every line of him. Men felt terror on seeing him rather than an inclination to laugh.

“What I shall do”—he spoke as though he had a full audience of his subordinate rulers about him instead of one subservient official—“is to make of their deaths a great spectacle. Listen to me, Onegesius, and make certain that you carry out my orders without slip or omission. Summon everyone tonight to the square. There must be a special place, raised above the rest, for the heads of states who have obeyed me, and for the generals and the officers of my household. There must be another space kept clear where all eyes can rest on it. Here there will be a row of ten seats and the block will be set up in front of them. I shall not be there. For the moment I have ceased to be one of you. I am the power above who has decreed the punishment.” He suddenly threw out both of his arms and cried in an angry voice, “I am too weighed down with burdens caused by the disloyal conduct of these men to waste time in seeing them die!”

He fell into a silence while he continued to pace the room, with a rolling gait like a sailor’s.

“The first night—tonight—only two of them will die. Lots will be drawn beside the block while the ten traitors watch. The two whose names come out will have their heads chopped off at once. Tomorrow night there will be the same ceremony and two more will die by lot. This will continue until they have all paid the penalty of their disobedience. Onegesius, you are to find ways of making this a spectacle which no one in the world will forget. Perhaps it should be decreed that the ten traitors sit in that grim and uneasy row in sackcloth. I leave all that to you.”

Onegesius did not venture any further opposition. “It is your will, Great Tanjou,” he said. “It shall be done.”

2

At noon each day Attila repaired to the Court of the Royal Wives. Hun women were not subjected to the strict rules of the East which confined women to the harem and turned them into closely swathed wraiths with faces hidden from alien eyes. The wives of Attila’s bowlegged warriors were free to come and go, to gossip, to stand in their doorways and toss insults at passers-by. But these rules had to be amended where the royal household was concerned. The leader of the Hun people had too many wives for that. Infidelity would soon raise its head if this large accumulation of neglected womankind were allowed to mix freely with the world. Accordingly they were kept in a town within a town, a collection of small houses behind a twelve-foot log wall. Behind this wall they were allowed every liberty accorded the wives of general or councilor or bowman.

Usually Attila donned his best attire for this pleasant daily function, a tunic of blue silk which fell to his knees and was elaborately embroidered with gold, and a three-cornered hat centered with a large ruby and an eagle’s feather. But it had been most unseasonably hot and all through his hours of toil that morning the great conqueror had worn nothing to cover his thick torso. He rose slowly to his feet and scowled at the sun.

“I am pressed for time and in any event it is too hot to dress,” he grumbled. “My little lotus blossoms will have to take me as I am.” He looked about him and called in a sharp tone: “Giso!”

His personal attendant, who had not been visible for hours, appeared instantaneously. He was fat and greasy and, even in a race noted for the flatness of its snouts, he had undisputably the ugliest of all human noses. He walked with a stiffness of gait which would have puzzled anyone who did not know that Giso had been born a slave. It was the amiable custom of the Huns to cut the sinews in the heels of their slaves to prevent them from running away.

The attendant stopped short and regarded his master with a questioning eye.

“Has the blue tunic worn out at last?”

“The blue tunic is as good as ever.” Attila was parsimonious to an extreme degree, grudging every coin which had to be spent for anything save the maintenance of his great army. The garment in question was the only one he possessed which had any pretensions to elegance. It had served on all state occasions for many years.

Giso was the only man in the Hun empire who dared to trifle with the white-hot temper of Attila. He grinned broadly. “What a pleasure this is going to be!” he said in a low tone, but one loud enough to carry to the imperial ears. “What a treat for all the little hearts fluttering so furiously behind the high wall.”

Attila eyed him with every evidence of distaste. “I sicken of your stale jokes,” he said. “Someday soon—it may be this very day—a spirit will make its way up into the clouds. The head it carries tucked under its arm will be yours.”

Giso always knew when he had gone too far. He was prompt to make his peace. “I will not care,” he said, “if it is from one of the seven hills of Rome that my spirit takes its departure. But I must see you standing there with all the world at your feet before I die.”

They turned their steps, debating bitterly as they went, to the center of the huge clutter of plain log buildings which made up the capital of Attila. Guards with drawn swords stood outside the gate of the Court of the Royal Wives and they shouted, “The Lord of the Earth, the Mighty Tanjou!” as soon as the half-naked figure of Attila appeared there. The cry could be heard repeated from all parts of the temple of femininity until the loud beating of a brass gong drowned out other sounds.

It had once been the custom for all of the wives to rush out from their small houses on his arrival, dressed in their best, and most shrill and excited in their welcome. Attila had enjoyed this kind of reception at first. He liked to pat and pinch the ones nearest him and to bandy coarse jokes with them. Gradually, however, he had lost his taste for it, finding it easier to select his wife for a day and a night without all of them clamoring for his attention. It happened that he had taken forcible possession of a Grecian city in the course of his quarrels with Constantinople some two years before and one of the prisoners was a Roman official named Genisarius. It was known to Attila, who gleaned every little bit of information which might be useful from the reports of his spies, that Genisarius had been in charge of a royal household and had kept it in ease and quiet. The apprehensive prisoner was placed accordingly in charge of the busy village of the conqueror’s wives, and with the use of systems of his own had brought peace out of chaos.

Attila was conscious that scores of bright eyes were watching him from the corners of windows and by other surreptitious methods. This pleased him and he strutted a little and puffed out his deep chest. He was not well pleased, however, when he saw that a member of his huge establishment had seen fit to disobey the order openly. In a small back yard there was a patch of red which resolved itself on closer scrutiny into the figure of one of his wives. She was leaning on the bark fence and watching him intently.

The fact that this particular wife was the possessor of a dark and lively eye and was moreover of a pleasant plumpness did nothing to diminish Attila’s displeasure. He racked his mind to recall her name and finally succeeded.

“That is Attamina, is it not?”

Giso nodded. “Attamina it is, and if you have any desire for my opinion, she is one of the best of the lot.”

“I seldom desire your opinion, and certainly not in this.”

Not daunted in the least, Giso volunteered some information about the solitary and somewhat pathetic figure in the bare yard. “You got her in one of those towns in Moesia that we sacked so thoroughly. The place had been burned and we thought everyone was dead. The officer you sent to investigate came across this one hunting through the refuse for food. Her face was black and she was nearly naked and she spat like a wolf cub when he dragged her in so you could look her over.” Giso gave his head an admiring nod. “Ah, Mighty Tanjou, what an eye you have for them! You said at once, ‘She will be worth while when she has been cleaned up. Bring her back after she has been washed and fed.’ ”

“She was worth looking at,” declared Attila, with a reminiscent twinkle.

“You have not sent for her,” said Giso, after making a mental calculation, “for more than three years.”

The good humor which had been slowly winning its way to the surface in the royal mind deserted him completely at this. “Oaf and slave!” he cried. “Is it concern of yours what I do about my wives? I will not have you spying and keeping count on me in this way!” He looked in the direction of the disobedient wife and was startled to see her raise her hand in a wave of greeting. “She has never learned to obey,” he said, in a grumble of annoyance. “Still, I must call her in again. I’ve been forgetting how diverting she used to be. She was like a wolf cub.” He frowned at Giso as an indication that his lack of tact had not been forgiven. “Go and warn her that the laws of the household are not to be broken in this way.”

Most of the houses were small, containing not more than one room, but there was one which towered above the others and had rounded pillars at each corner. This was the house of Cerca, who had been the favorite wife for some years because she was the mother of his oldest son, Ellac. There were many rooms in Cerca’s house and the furnishings were quite luxurious. She was not subject to the rules which bound the other wives. This was made evident when she came down the steps to greet him as he passed.

Cerca was no longer young. There were wide streaks of white in her hair (apparently she scorned the use of dye to which most women resorted) but she had kept herself slender. Her richly embroidered dress of scarlet and gold was in good taste. She smiled invitingly.

“I have seen little of you of late, O Great Tanjou,” she said. Her voice was pleasantly modulated.

Attila stopped. “Has it not come to your ears that I am raising the largest army the world has ever seen? That I am on the point of embarking on the greatest war in all history?”

The favorite wife smiled. “I listen eagerly to everything I can hear about your plans. But, O Mighty King, you so seldom see me when you visit us now. Sometimes you notice me and smile. Sometimes you brush past me as though I do not exist.”

“My mind is filled with many things,” muttered Attila. It was clear that he was uneasy. It was no secret to those about him that this fierce and unforgiving man was indecisive in matters which pertained to his wives. He often tried to evade the issues which the size of his household created.

The fine dark eyes of Cerca compelled him to look at her. “I must talk with you,” she said, in a tone half pleading, half insistent. “Have you forgotten the long talks we used to have? There was a time when you thought my opinion worth while and you liked to tell me about yourself. You even told me how much you hated that Roman boy Aetius, and how you became uncomfortable and silent when he was around and displaying his graces. I think perhaps, O Mighty Lord and Master, I was the only one you ever confided in to that extent.”

Attila frowned at her impatiently. “Why are you stopping me to tell me this?” he demanded.