0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

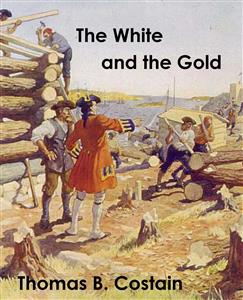

A thorough overview of early Canadian history, told in the matchless style which marks the best of Costain, here is the vast panorama of a mighty land, of its vivid and violent people and of the turbulent centuries through which it grew to greatness. Here is the intimate, living story of the making of Canada!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The White and the Gold: The French Regime in Canada

by Thomas B. Costain

First published in 1954

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

The White and the Gold: The French Regime in Canada

To All My Friends in Canada

Introduction

THERE have been many histories of Canada, and some of them have been truly fine, but it seemed to a group of writers, all of whom were Canadians or of Canadian stock, who met a few years ago, that the time had come for something different. We all felt the need for a version which would neglect none of the essential factors but would consider more the lives of the people, the little people as well as the spectacular characters who made history, and tell the story with due consciousness of the green, romantic, immense, moving, and mysterious background which Canada provides. In addition there was a strong feeling—and this clearly was the governing impulse—that Canada’s rise to nationhood should be traced to the present day, when the land which was once New France and then the Dominion of Canada promises to develop into one of the great powers of the globe.

This, it will be allowed at once, was what might be termed a rather tall order. However, there was considerable discussion about it, both then and later, and the outcome was a plan to do a formidably long version, all the way from John Cabot to St. Laurent. It was to be the joint work of a number of Canadian writers, one for each volume, and perhaps as many as six volumes.

It fell to my lot to begin, and this volume tells the story of the earliest days, the period of the French regime, concluding near the end of the seventeenth century. It has been with me a labor of love. Almost from the first I found myself caught in the spell of those courageous, colorful, cruel days. But whenever I found myself guilty of overstressing the romantic side of the picture and forgetful of the more prosaic life beneath, I tried to balance the scales more properly; to stop at the small house of the habitant, to look in the brave and rather pathetic chapel in the wilderness, to stare inside the bare and smoky barracks of the French regulars. It is, at any rate, a conscientious effort at a balanced picture of a period which was brave, bizarre, fanatical, lyrical, lusty, and, in fact, rather completely unbalanced.

No bibliography is appended because I found, when the time came to prepare one, that the point of no return had been reached. A list of roughly a thousand items—books, papers, extracts, manuscripts—which had been read or, at least, dipped into, would be of small value because of its very size. I shall content myself, therefore, with the perhaps obvious statement that in writing of this period two great sources constitute a large part of the preparation, that uniquely conceived and organized mass of remarkable material, the Jesuit Relations, and the crystal-clear reconstruction in Francis Parkman’s splendid volumes.

The second volume, which will deal with the period of the English and French wars, is now being prepared by Joseph Lister Rutledge, for many years editor of the Canadian Magazine and a fine scholar with the capacity to keep a great event equally great in the telling.

Thomas B. Costain

January 1, 1954

CHAPTER I

John Cabot Speaks to a King—and Discovers a Continent

1

IT MAY seem strange to begin a history of Canada in an English city, a bustling maritime center of narrow streets in a pocket of the hills where the Avon joins the Severn. But that is where the story rightly starts: in the city of Bristol, which had become second only to London in size and was doing a thriving trade with Ireland and Gascony and that cold distant island called Iceland which the Norsemen had discovered. It starts in Bristol because a Genoese sailor, after living some time in London, had settled there with his wife and three sons, one John Cabot, or “Caboote” as the official records spelled it, a sea captain and master pilot of some small reputation. He arrived in Bristol about 1490, when the place was fairly bristling with prosperity and the streets had been paved with stone and the High Cross had been painted and gilded most elaborately, and out on Redcliffe Street the Rudde House stood with its great square tower, the home of those fabulous commoners, the Canynges, as evidence of the wealth which could be gained in trade.

It was not strange that little attention was paid at first to this dark-complexioned, soft-spoken foreigner. Bristol, aggressive and alive to everything, had been fitting out ships to explore the western seas in search of the “Vinland” of the Norse sagas and the legendary Island of the Seven Cities which had been found and settled more than seven centuries before by an archbishop of Oporto fleeing the conquering Moors with six other bishops. The waterfront buzzed with the strange new talk which had been on the tongues of sailors for years, the suddenly aroused speculations as to what lay beyond the gray horizon of the turbulent Atlantic. The men of Bristol doffed their flat sea caps to no one. What had they to learn from a mariner who knew only the indolent ease of southern seas, most particularly of the Mediterranean, where the leveche blew insistently across from Africa with a dank hot scent?

But then it became known that another of these bland-tongued fellows, one Christopher Columbus, had set sail westward from Spain with three small ships and had found land hundreds of leagues across the gray waters, and that because of this Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain were claiming all the trade of Cathay. Bristol recalled that this man John Cabot had been voicing the same theories which had induced Their Most Christian Majesties to gamble a fleet on such a thin prospect. Cabot also had said that the world was round and that the shortest route to Cathay and Cipango led straight west. They got out their charts and compasses now and with new respect listened to him expound his belief that where Columbus had landed was the midriff of Asia and that the way around the world would be found far to the north. This was heady talk. It meant that there were still lands and seas to which Spain could not yet lay claim, that the flag of England could lead the way to equal wealth and glory. It was decided to seek royal sanction for a venture well to the north of the route which the inspired Columbus had taken.

Henry VII was King of England at this time and he was not exactly popular in Bristol. In the year 1490 he had paid the city a ceremonial visit and had received a truly royal welcome; but on leaving he had shocked them by laying a fine of five per cent on all men worth in excess of twenty pounds. Their wives, he said, had broken some dusty and long-forgotten sumptuary law by dressing themselves finely in his honor. He had called this fine a “benevolence,” but the outspoken Bristol men had found other words for it. The seventh Henry, in point of fact, had little gift for winning the hearts of his subjects. The first of the Tudor kings was able and farseeing, but he was cold, withdrawn, hating no man but loving none, incapable of much enthusiasm save for the gold he was accumulating through the efficient raking of the legal fork of Morton, his chief minister.

Henry was eager, it developed, to share in the spoils of the west and so letters patent were issued to John “Caboote” and his three sons, Lewis, Sebastian, and Sancius, to set sail with five ships, to be paid for with their own money, and “to seek out, discover and find whatsoever islands, continents, regions and provinces of the heathens and infidels in whatever part of the world they be, which before this time have been unknown to all Christians.” It was stipulated that they were to raise the flag of England over any new lands they found and to acquire “dominion, title and jurisdiction over these towns, castles, islands and mainlands so discovered.” The only restriction laid upon them seems to have been that they must not venture into the south, where they would be poaching on the Spanish domain.

The parsimonious King had carefully protected himself from any possible loss, but he stipulated nevertheless that he was to receive one fifth of any profits which might accrue. It was provided in return that the Cabootes were to have as their reward a monopoly of trading privileges and that Bristol was to benefit by being the sole port of entry for any ships which engaged in the western trade. This laid the financial responsibility squarely in the laps of the men of Bristol, and it was not until the following year that they were able to organize their resources for the effort. Early in May 1497 a single ship called the Matthew, a ratty little caravel, set out for the west with John Cabot in command and a crew of eighteen men; surely the meanest of equipment with which to make such a hazardous and important venture. It was with stout hearts and high hopes, nevertheless, that the little crew gazed ahead over the swelling waters of the Atlantic, their parrels well tallowed and their topmasts struck to the cap in the expectation—nay, the certainty—of rough weather ahead.

In the fifteenth century the mariner had few instruments to guide him on his course. When the weather was clear he could sail with his eye fixed on the North Star; if it was overcast he had to use the compass. The North Atlantic is more likely to provide fogs and gray skies than clear sunshine, and so it was the compass on which John Cabot had to depend. This meant that he did not sail due west, for the compass has its little failings and never points exactly north. In the waters through which Cabot was sailing the variation is west of north, which meant that the tiny Matthew, wallowing in the trough of the sea, its lateen sail always damp with the spray, followed a course which inclined slightly southward. This was fortunate. It spared the crew any contact with the icebergs which would have been encountered in great numbers had they sailed due west; and it brought them finally, on June 24, 1497, to land which has been identified since as Cape Breton Island.

The anchor was dropped and the little band went ashore gratefully, their hearts filled with bounding hopes. The new land was warm and green and fertile. Trees grew close to the water’s edge. The sea, which abounded with fish, rolled in to a strip of sandy shingle. They saw no trace of natives, but the fact that some of the trees had been felled was evidence that the country was inhabited. All doubts on that score ended when snares for the catching of game were found. Perhaps eyes distended with excitement were watching the newcomers from the safe cover of the trees; but not a sound warned of their surveillance.

John Cabot, raising a high wooden cross with the flag of England and the banner of St. Mark’s of Venice (that city having granted him citizenship some years before), had no reservations at all. He was certain he had accomplished his mission. He knew that his feet were planted firmly on the soil of Cathay, that fabulous land of spices and silks and gold. Somewhere hereabouts he would find the great open passage through which ships would sail north of Cathay and so in time girdle the earth.

2

It is unfortunate that so many of the great men of early Canadian history are little else but names. John Cabot, who thus had become the discoverer of North America, is wrapped almost completely in the mists of the past. A few dates, a phrase or two from letters of the period, an odd detail shining out of the darkness like a welcome ray of sunshine; these make up the sum total of what is known about him. There is no record of his appearance, whether he was tall or short, stocky or thin. His nationality suggests that he was dark of complexion, but even this remains pure speculation. It is not known when and where he died, although it is assumed that he spent his last days in Bristol.

This much is known: that he and his faithful eighteen, all of whom seem to have returned alive, were given a tumultous welcome in Bristol and that all England joined later in the chorus of acclaim. Cabot became at once a national hero. He was called the Great Admiral and wherever he went, according to a letter written by a Venetian merchant residing in London, “the English ran after him like mad people.” He seems to have had a broad streak of vanity in him because he began to dress himself handsomely in silks and, presumably, to affect the grand manner. He distributed conditional largesse with a lavish hand, granting an island (to be chosen and occupied later) to this one, a strip of land to another. He gave it out rather grandiloquently that the priests who had volunteered to accompany the second expedition were all to be made bishops in the new land. From these details it may be assumed that he strutted and posed and made the most of his brief moment of glory.

That much may be said without detracting from the credit due him: he had been cast in the mold of greatness. Before Columbus set out, John Cabot had been expressing the same beliefs and theories as his never-to-be-forgotten countryman and had been striving hard for support in putting them to the test. He had ventured out on the most perilous of voyages in a cockleshell of a ship and with the most meager of crews. He possessed, it is clear, the fullest share of knowledge and courage and resolution. He had mastered the crises of the crossing and had accomplished his purpose before turning homeward. He was entitled to strut a little, to carry his head high, to play the role of destiny’s favorite.

It is probable that he had audience with the King before the letters patent for the first voyage were issued, although there is no record of such. That the Great Admiral was granted a hearing after returning in triumph can be taken for granted; and it is likely that more hearings followed. It is known that both the King and the explorer were in London during the early part of August and that the old city fairly seethed with excitement. On August 10 the King recognized Cabot’s merit by making him a present from the royal purse of ten pounds!

Henry had been King for twelve years only but he had already begun the systematic sequestration of funds in secret places which yielded on his death the sum of £1,800,000, a truly fabulous estate for those days. Already he was entering into the conspiracy of extortion which his various crafty ministers (most particularly Empson and Dudley, who had succeeded Morton, he of the Infallible Fork) were carrying out. He frequently consulted Empson’s Book of Accounts and wrote suggestions on the “margent” for new and tricky methods. It is a measure of the man that out of his amazing hoard he could spare no more than ten pounds for this brave and skillful mariner who had brought to him the prospect of an empire as great as that of Spain.

Henry VII was, however, a man of many contradictions. With his parsimony went a love of ostentation and display. He liked to robe himself with all the grandeur of an eastern potentate, in silk and satin and rich velours, his broad padded coats embroidered with thread of gold and weighed down with precious stones, with massive gold chains around his neck and pearls as big as popcorn on his garters. He maintained a rather brilliant court and he kept a good table, which meant there was an earthy side to him; so good a table, in fact, that Ruy Gonzales de Puebla, the Spanish Ambassador, who was meagerly maintained by that other royal miser, Ferdinand of Spain, dined continuously at the royal board. He encouraged the New Learning and gave passive support at least to Colet and Grocyn at Oxford. He was a steady patron of a commoner named Caxton who was printing books from type for the first time in England. The first king to mint pounds and shillings, which had previously been nothing more than coins of account, he saw to it that his own unmistakable likeness in truly royal raiment was stamped upon them.

Henry was steering the ship of state through waters roiled by hate and conspiracy and imposture, and his success is proof of his capacity for judging men shrewdly. Looking down his quite long Welsh nose with his crafty gray Norman eyes, he must have sized up the Genoese captain, “he that founde the new isle,” as a likely instrument for the further extension of his power and wealth. The ten pounds were followed sometime later by the grant of an annuity of twenty pounds sterling. But Henry was not committing himself to this great extravagance. The annuity was to be paid out of the customs of the port of Bristol, and he was not prepared, one may be sure, to countenance any diminution of the sums which reached him annually from that source. The responsibility was laid on the shipowners and merchants of Bristol, and most particularly on the shoulders of one Richard ap Meryk, who held the post of collector, the same relatively obscure official for whom the absurd claim was made later that the new continent of America had been named in his honor.

The King no doubt had many talks with John Cabot, for his enthusiasm showed a steady rise in intensity. New letters patent were issued by which Cabot could take any six ships from any of the ports of England, paying for them (out of his own pockets or the money chests of his Bristol backers) no more than the amount the owners could expect if their vessels had been confiscated for royal use, which would be a pretty thin price. The right was given also to the Great Admiral to take from the prisons of England all the malefactors he could use in the new venture. The King was to get his commission on any and all profits. Henry went this far in lending his support: he would advance loans from the royal purse to those who fitted out ships for the expedition. It is on record that he loaned on this basis twenty pounds to one Lanslot Thirkill of London and thirty pounds to Thomas, brother of Lanslot.

The winter was spent in preparations which rose to a fever point. Not only did the shipping interests of the country show a willingness to invest, but the desire to participate manifested itself in other ways. Men from all levels of society expressed the desire to be taken along. The merchants of London were eager to share in the trading end of the great adventure and sent to Cabot stores of goods to be used in barter with the inhabitants of the newly discovered land—cloth, caps, laces, points (the leather thongs with which men trussed up their leggings and trousers, the forerunners of the suspender, a most doubtful item of exchange with bare-skinned Indians), and many other items and trifles which were thought likely to attract the heathen eye.

The second expedition, which carried three hundred men and so must have consisted of many ships, sailed from Bristol early in May of the following year, 1498. The bold little ships had their holds well stocked with provisions, and with them went not only the hopes of those who had invested their money in the venture and the ardent expectations of all who had received promises of great estates and island domains from the lavish leader, but the support of every Englishman from the acquisitive King to the humblest denizens of hovel and spital-house.

3

The second expedition proved a failure because it started with a faulty objective. Cabot expected to find open water to the north of the new continent which would provide a route around the world. The ships arrived first at Newfoundland, which the leader called the Isle of Baccalaos because the natives used that name for the fish abounding in the waters thereabouts. Later it was learned that the Basque people used the same word for codfish, and this raised the suggestion that Basque ships had preceded Cabot in reaching this part of the world. From Newfoundland the fleet turned north in pursuit of that mirage, the Northwest Passage. They found themselves soon in seas filled with icebergs. This was disconcerting, but nothing could shake their conviction that they must sail ever northward.

Sebastian Cabot, the second son of the commander, was with his father, and it is from a later document, based entirely on his recollections, that the story of the expedition is drawn. Although the season was now well advanced, the majestic icebergs rode the seas in such numbers that there was constant danger of collision. The shores were bare and inhospitable, becoming less and less like the rich lands of Cathay which they sought. At one point, which was believed later to have been Port of Castles, the commander was convinced that he had discovered the mythical Island of the Seven Cities, and there was much excitement as a result. He had mistaken the high basaltic cliffs for the turrets of castles. He persisted in his error sufficiently to report the occurrence later, but it is clear that at the time no effort was made to get closer to where, presumably, the descendants of the seven bishops still lived.

The weather became so cold and uncertain that the northward probe had to be abandoned. Sick at heart and still convinced that the route around the world lay in the north, they finally gave up the quest and turned back.

A determined effort was made then to find some source of wealth in the lands lying south of Newfoundland. The fleet took a south-westerly slant which carried them to Cape Breton and Nova Scotia. Sebastian Cabot, who later achieved a high reputation as a cartographer and maritime authority generally, seems to have possessed the highly unscientific habit of exaggeration. His report of the last part of the journey leaves the impression that the ships from Bristol sailed as far south as the Carolinas, but this obviously was impossible, for they were back in England before the end of the summer. They had found nothing new, they had not seen a single inhabitant, their reports depicted the new continent as bare and grim and, above everything else, silent. They brought back nothing to compensate for the expense of the expedition save cargoes of fish.

On Cabot’s return England seemed momentarily to lose interest in North America. This strange land had nothing to offer, no silks, no gold, no precious stones. It had no castles save the glistening towers of ice which floated in the sea. The investors had wasted their money and their ships in an unprofitable venture. Lanslot Thirkill and Thomas of that ilk still had loans from the King to pay off, at a good interest, no doubt. The benefactors of Cabot’s freehanded generosity could whistle for their grants of land. The priests who were to have been made bishops returned to much humbler shares in the activities of Mother Church.

Nothing more is known of John Cabot. It is probable that he died within a relatively short time, for there is no record of the payment of the pension beyond the first two installments. His descent into oblivion was rapid and complete. His son Sebastian lived to a ripe old age and held important posts under the rulers of Spain. His boastfulness as to the part he had played in the explorations of his father made him the central figure in bitter controversies centuries after his death; into which it would be unprofitable to enter here.

England had lost a great opportunity. Nothing was done to colonize the lands which Cabot had found, although the fisheries of Newfoundland were developed by enterprising captains from Bristol, St. Malo, and the Basque and Portuguese ports. While Spain was achieving world leadership through the wealth which followed her vigorous conquest of the continent Columbus had discovered, the Tudor monarchs made only ineffectual efforts to follow up the discoveries of Cabot.

Small things have often swayed the course of history. If an arrow shot into the sky had not lodged in Harold’s eye, the Normans might conceivably have been defeated at Hastings. Two centuries after Cabot’s death a merry little tune, whistled and sung to seditious words and called Lillibulero, would play quite a part in ousting a bad king from the throne of England. Perhaps to the list this may be added: that the grant of ten pounds by a parsimonious king to the man who had found a continent may have put a damper on individual enterprise in following up his exploit and so resulted in the temporary loss of this great land which later would be called Canada.

CHAPTER II

Before and after Cabot

1

ALTHOUGH John Cabot had supplemented the discoveries of Columbus by proving the existence of a continent in the North, he was not the first European to set foot on what is now called North America. The Norsemen had discovered Iceland and Greenland long before men of their own race took possession of Normandy, and certainly many centuries before men began to discuss seriously the possibility that the earth was round like the stars in the sky. The rugged men from the North established permanent settlements on both islands. In the year 986 a Viking captain named Bjarne Herjutfson was sailing for Greenland and became lost in foggy weather. He was driven far off his course and came to a land which he knew was not Greenland because it was covered with tall green trees and was very pleasant and warm. Bjarne was so anxious to reach his objective that he made no effort to learn about these strange new shores. After he arrived he told the story of what he had seen and in time it was carried back to Norway. The feeling took hold of the Viking people that some effort should be made to investigate.

In the year 1000, accordingly, a bold young sea captain named Leif, a son of Eric the Red, who had already made his home in Greenland, decided to take the task on his shoulders. He reached Greenland and bought from the less enterprising Bjarne the ship in which the latter had made his voyage, believing, no doubt, that it would bring him luck. With a crew of thirty-five he ventured into the warmer seas which lay to the south and west.

Leif made three landings. The first was on a coast which was cold and flat and snowbound. This he named Helluland and it was, without a doubt, somewhere on the coast of Labrador. After a further venture of several days’ duration into the southward they came to a land of much fairer promise. Here there were tall trees and the air was mild and there were beaches of fine sand. Leif called this country Markland. It might have been Cape Breton or Nova Scotia, although it is hard to believe that the ship could have missed Newfoundland on the way. Finally they came to a delightful coast which seemed to the weary crew like the Valhalla where they all aspired to go after death. It was a land, to quote from the Norse saga, where even the dew on the grass had a sweet taste and the salmon were the largest ever to delight the eyes of men. There were vines along the beaches carrying great crops of grapes, and so they called this gentle country Vinland. They wintered there in great comfort and content and returned to Greenland in the spring.

The Norse settlers in the far North were very much excited by the reports Leif and his men brought back with them. In the course of the next few years other parties set out to cover the same course and some of them succeeded in locating Vinland. Leif’s brother Thorwald was one of the first and he spent two winters in that land of warmth and plenty. It was Thorwald who located the first natives. They were men with copper-colored skins, of great physical strength and savage disposition. These red men were armed with bows and arrows and they had boats made of the skins of animals in which they got around with amazing dispatch. Thorwald was killed in a brush with them and he was buried, in accordance with his wish, under the green sod close to the shore and within hearing of the slow-breaking combers.

A determined effort to settle Vinland permanently was made a few years later, in 1007 to be exact. A young Norseman named Thorfinn organized a fleet of ships and set out with a considerable company. There were one hundred and sixty men in the party as well as a number of women. They took a herd of cattle with them and they built houses and cleared land for cultivation, after which they turned the cattle out to pasture on the thin outcropping of vegetation along the beaches. Thorfinn’s wife had accompanied him, and a son was born to them who was given the name of Snorre and who enjoyed, therefore, the honor of being the first white child born on the continent of North America.

The natives were becoming openly hostile to the efforts of these white-skinned intruders to settle down permanently in their hunting and fishing grounds, and the period during which Thorfinn and his companions remained in Vinland was one long and bloody struggle with the resentful redskins. So many of the Vikings were killed that finally they gave up the effort to remain and returned reluctantly to a grim and iron existence on Greenland’s icy mountains.

Just where Vinland was has never been settled to the complete satisfaction of scholars, although it has been conveniently assumed that it was one of the islands lying south of Rhode Island and Cape Cod. Much of the evidence points that way, although grapes could have been found farther north. The remnants of a stone mill, which has been labeled the Newport Tower, have been found on the southern coast of New England and there are clear indications that it was the work of Scandinavians.

There is one point of evidence which inclines some scholars to a belief that the northern part of Newfoundland was as far south as the wandering Norsemen reached. In the Flateyjarbók, which is the chief authority for the stories of Norse exploration, it is stated that on the shortest day at Vinland the sun remained above the horizon from seven-thirty in the morning until four-thirty in the afternoon. However, the word used to designate the closing hour of daylight is “eykarstad,” and there has been much dispute as to whether this particular word means four-thirty or three-thirty. If the latter is the accurate definition, the shortest day was no more than eight hours long, and that would place Vinland close to Latitude 50. In other words, it must have been somewhere on southern Labrador or the northernmost portion of Newfoundland.

The latest contribution to the controversy has been the finding of mooring holes in rocks on Cape Cod. Now the mooring hole is a device used by the Vikings, and the Vikings only, a hole in the granite boulders of the fiords into which an iron rod would be slipped to keep a vessel fast to shore. This find has been acclaimed by many scholars as proof that Vinland was Cape Cod. It seems a reasonable assumption.

The fact is thoroughly well established, therefore, that the Norsemen found North America and paid many visits to it. Quite recent discoveries hint at more determined efforts on their part to investigate the new continent. There is the Kensington Stone in Minnesota which is covered with runes from the fourteenth century—quite recently relics have been discovered which are unquestionably of Norse origin—heavy battle-axes, swords, spears, a fire-steel of the late Dark Ages. Did the hardy Norsemen, at some date much later than the Vinland adventures, strike far inland and reach the valley of the Red River? It is a fascinating subject for speculation, but until more evidence comes to light it can be nothing more than that.

2

The efforts of the English to follow up the discoveries of Cabot included an expedition sent out in 1501 by the merchants of Bristol. It was headed by three Englishmen, named Ward, Ashhurst, and Thomas, and three Portuguese. Nothing is known about what they accomplished, but it is recorded that Henry VII gave them five pounds on their return. In 1522 there was a different king in England, Henry VIII, and in his forthright way he made it clear to the merchants of London that he expected them to do something about North America. The bluff young king was already spending with a lavish hand the magnificent fortune his father had saved so slowly and carefully, but he had no thought of applying any of it to the proposed expedition. He told the heads of the London guilds that he would be content with nothing less than a fleet of five ships, well manned and provisioned. The merchants were not seafaring men; they were vintners and mercers and goldsmiths, and averse to anything but the management of their countinghouses. They had no stomach for adventure, and it was only in response to the King’s hectoring that they finally equipped two of the smallest ships they could find, named the Samson and the Mary of Guildford. The unlucky Samson, caught in a mid-Atlantic storm, went down with all on board, but the Mary weathered the blow and conducted a reconnaisance of the American coast which ended off the island of Puerto Rico. Here she encountered a welcome from the Spanish in the form of a salvo of cannon fire. The Mary very sensibly turned about and sailed for home.

There was something ephemeral about all the efforts at exploration which followed immediately after the success of Cabot. Many ships crossed the Atlantic without adding anything tangible to the world’s knowledge. The thought of colonization does not seem to have entered the calculations of anyone. They were still looking for the magic passage which would give an entrance to Cathay and the easy rewards of gold and precious stones and rich fabrics. One of the most resourceful of the explorers was a nobleman of the Azores named Gaspar Corte-Real, who sailed from Lisbon and was the first to penetrate into Hudson Strait. He packed the holds of his two ships with natives and took them back to Portugal, where they were sold as slaves.

France had no part in this until Francis I came to the throne in 1515. He was twenty-one years old, ambitious and gifted and spoiled by the atmosphere of adoration in which he had been raised by his mother and his older sister. He had a long straight nose and long straight legs and he was a sybarite by disposition. There were two other youthful monarchs sitting on great thrones at this point in history. The burly Henry VIII had been King of England for six years, and it was acknowledged by all his courtiers that he was the best rider, the best wrestler, the best singer and composer, the best player at cards, the best jouster, in fact the best at everything in the whole kingdom of England. Because of the mortality in the family of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain the succession had come to Charles, son of their second daughter, Joanna, who had married Philip, the heir of the Hapsburgs, and had died in madness. Thus Charles, the fifth of his line, succeeded to all the Hapsburg dominions as well as Spain. He had Austria and Sicily and the Netherlands and all of America, and at the age of twenty for good measure he was elected Holy Roman Emperor. Charles was a reserved young man, with a clear head and a sagacious eye and a jaw which jutted out in an exaggeration of the Hapsburg profile. He might lack the graces of Francis and the swaggerie of Henry, but in point of capacity and unswerving purpose he was without a peer.

Nothing would suit Francis the Sybarite, the finest dresser in all Christendom, but that he must outshine his two rivals. Obviously he could not allow them a monopoly in this matter of opening up the New World in the west. He, the darling of the gods, must project himself into this contest in globe-girdling. Shrewdly enough he fixed his eye on one Giovanni de Verrazzano, who had just returned from a very successful venture in buccaneering in the waters which later became known as the Spanish Main, with plenty of gold and silver in his hold and a price on his head. This bold and able captain was sent out from Dieppe in 1524 with four ships and instructions to establish the claims of France to some slice of the great new continent. Verrazzano found that only one of the vessels, the Dauphine, was seaworthy. Leaving the others behind, he reached the coast of the Carolinas in the Dauphine and from there made his way north to Belle Isle between Newfoundland and Labrador. He noted the possibilities of a harbor where a broad river (later called the Hudson) came down to the sea. He lingered here a short time and then went on, having been visited with no prophetic vision of enormous white towers reaching up into the sky and streets like echoing canyons. He took back to France plenty of evidence that the northern half of America was rich and temperate and ripe for exploitation; and if the new King had been a ruler of determination and singleness of purpose the result would have been an earlier move to acquire this great new country. But by this time Francis had become involved in a struggle with Charles V and was commanding an army in Italy. Within a year the ambitious dilettante was defeated and captured at the battle of Pavia and carried off to Spain as a prisoner. The American project languished for years as a result. In the meantime Verrazzano came to an untimely end, being captured, according to one report, by the Spaniards and hanged in chains as a pirate.

While this went on, of course, fishing boats continued to ply back and forth each year between the western ports of Europe and the waters of Newfoundland. Bristol was supplying a good part of England with the fish brought back in the holds of her sturdy ships, and the port of St. Malo was doing the same for France. As many as a score of ships went out to the Grand Banks every season. They were content with this small share of the wealth of the new-found continent. No one guessed how close they were to a tremendous secret; that just behind the Island of Baccalaos (this name being still commonly used) there was a gulf shaped like a great funnel of the gods into which a majestic river poured. This beautiful river rolled down seaward from a string of the largest lakes in the world through a transverse valley of more than half a million square miles. Its estuary was so vast that its salt waters exceeded all other river systems put together. The fishermen would have been little concerned if they had known that in the two thousand miles of this new continent a new nation would be nurtured, but their eyes would have gleamed with excited speculation if they had been told of the tremendous stores of gold in the Cambrian shield which bordered the northern rim of the basin.

The stout fishermen set their nets and hauled in their heavy catches. They talked of picking up gold someday on the streets of a mythical Cathay, but the words Quebec and Canada were never on their lips.

CHAPTER III

Jacques Cartier Discovers Canada

1

IT WAS a chill and overcast day, April 20, 1534. Gusts of wind swept across the old harbor of St. Malo, so rich in seafaring tradition. They caused a rustling in the sails of two small caravels, taut at their anchor chains. They were even more audacious, these April winds, for they fluttered the tails of the absurdly wide fur-trimmed cloak of Charles de Mouey, Sieur de la Milleraye, and displayed his wine-colored breeches slashed with yellow, and the jeweled bragetto at his belt. This was a great liberty, for Charles de Mouey was a vice-admiral of France and he stood, it was whispered, close to the King.

The explanation of the ceremony which was being carried out at the harborside was this: Francis had regained his liberty by swearing to certain terms which he repudiated soon after reaching his own soil and now he was free to proceed with other plans. Wondering perhaps if his honor, which he cherished like a maiden lady sighing over faded rose leaves, had survived the breakage of his liberation vows, he had decided to bolster it up by making another effort to establish a colonial empire in the West. The two caravels had been fitted out and provisioned, and crews of thirty men had been selected for each. The commander was to be a relatively obscure man who stood beside Charles de Mouey on this occasion, one Jacques Cartier, to whom the sum of six thousand livres had been granted for expenses.

Jacques Cartier stood high in the regard of seafaring men, so high in fact that Messire Honoré des Granches, chevalier and constable of St. Malo, had allowed his own daughter, Marie Catherine, to marry him. He was now forty-three years of age, a stocky man with a sharply etched profile and calm eyes under a high, wide brow; slightly hawk-billed as to mouth, it must be confessed, and with a beard which bristled pugnaciously. It was the face of a man who finds philosophic calm in contemplation of the sea but can be roused easily to violent action.

Jacques Cartier presented a distinct contrast to the fashionably attired admiral. He was dressed in a thick brown cloak, belted in tightly at the waist. The tunic he wore under the cloak was open at the neck, where a white linen shirt showed. This was not the garb of a gentleman; it was intended for hard wear and was as unpretentious as the street sign of an obscure glove merchant. His hat had nothing to distinguish it from the flat cloth caps of the crew save three modest tufts in the brim. A sober man, this, fair in his dealings, capable and without fear, and with a hint of power in his steady eyes. There was a thoughtful air about him as he listened to the silky tones of the admiral, whose chief nautical achievement had been, undoubtedly, to sail close to the wind of royal favor at court.

“It is my intention,” the great man was saying, “to require this of each and every member of the crews, that you stand before me in turn and swear an oath to serve faithfully and truly the King and your commander.”

Everyone knew what was behind this announcement. St. Malo did not favor any further efforts to open up the new continent. It was very pleasant and profitable for them as things stood, with the chance to fish in the most prolific of waters, free of governmental control and supervision. They did not want colonies on the shores of America, and regulations to fetter their movements, and great men like this furred and feathered admiral to keep them in line. Their attitude of sullen opposition was so well known that this oath had been deemed necessary to insure their obedience at sea.

Reluctantly, perhaps, the men came forward one by one and knelt before the admiral. His padded sleeves rustling with each movement he made, Charles de Mouey administered the oath to them. His manner said plainly, “An assistant could do this quite well enough, but I, an admiral of France, desire you to know that I spare myself no effort in the service of our sovereign lord the King, and that the same is expected of you.”

It has been said that the caravels were small. They were, in point of fact, quite tiny, not exceeding sixty tons each. They showed some considerable differences and improvements, however, from the equally diminutive vessels in which John Cabot had set out to sea. They stood higher in the water and the superstructures were elaborately carved. Under the quarter-deck of each caravel protruded four black-muzzled guns. These humble cannon would be of little use in a deadly hull-to-hull sea fight, but they gave Jacques Cartier a fine sense of conviction, that they could be depended on to emit enough heavy smoke and set enough echoes flying to scare all hostile intent out of the copper-skinned natives he expected to encounter.

And so the two little ships took off. The commander, his stocky legs planted firmly on the upper deck, his dark eyes fixed ahead, was convinced that this time there would be results, that he was leading the first practical effort to solve the enigma of the silent continent so far off in the west.

2

It is easy to believe that Jacques Cartier had guessed the great secret of what lay behind the island of Newfoundland. At any rate, he set about the solving of it with a directness which hinted at a sense of the truth. Fortunately he was a man of methodical habit and each night he sat down in his tiny cabin and with stiff fingers and a spluttering pen recorded each step of the voyage. Fortunately, also, he was articulate and so he left for posterity a quite graphic account of what was to prove the discovery of Canada.

It took the two caravels no more than twenty days to come within sight of Newfoundland. It happened that their first glimpse of that mountainous and formidable island was a pleasant one—Cape Bonavista standing up high over the sea with a hint of welcome. Bonavista Bay proved to be blocked with ice, however, and so Cartier found it necessary to shelter in a harbor a few leagues south. In gratitude for the safe ease he found here, the commander named it St. Catherine’s Harbor after the loving woman who had condescended to become his wife. His deep affection for her caused him to apply her name to many of the places he encountered in the course of his explorations.

As soon as the ships had been given an overhauling they started out again, sailing north for the narrow stretch of violent water between the northern tip of Newfoundland and the shores of Labrador. The fishermen, who swarmed around the eastern shore of the tall sentry island, had labeled this strait Belle Isle. Ordinarily it was a rough piece of water with the recession of the tides and the strong flow of the waters of the St. Lawrence seeking an outlet to the sea and, to make matters worse, a most unusual storm was raging when Cartier’s ships reached the eastern entrance. A violent wind from the west was taking hold of the hurrying current and whipping it into a maelstrom. No sailing vessel could make headway under these conditions. The caravels were hauled in to anchorage at what is now Kirpon Harbor and waited there for the storm to subside.

It is easy to believe that the tumultuous flow of waters through the strait had a significance for the commander of the expedition, who was, first of all, a master pilot. It must have appeared to Cartier that he was witnessing the liberation of tremendous waters. Was this, then, the eastern end of the Northwest Passage? One can imagine this man of calm eyes and aggressive jaw pacing his tiny quarter-deck and watching the down-flow with speculative eyes. “This is what I came to find,” he would be thinking. “Once we can get through, we will strike straight into the heart of Cathay.”

It was not until June 9 that the violence of the winds abated and it was possible to turn the noses of the caravels into the narrow passage. They found it plain sailing now and very soon were through the strait with open water ahead of them. They passed an island which the faithful husband named after his wife (Alexander the Great had set an example by naming six cities after himself) and came to Blanc Sablon. These dangerous shoals were described by Cartier as a bight with no shelter from the south and abounding with islands which seemed to afford sanctuary to enormous quantities of birds, tinkers and puffins and sea gulls. They passed the Port of Castles, but it was clear to them that what Cabot had thought were the turrets of great strongholds were no more than natural cliffs corroded to the shape of battlements; and so the story of finding the Island of the Seven Cities was dispelled. One day’s sailing brought them to Brest Harbor, where they dropped anchor. Cartier decided to use the ship’s boats for a further exploration of the north shore.

He came back disillusioned, realizing that this was not the long-sought-for Northwest Passage. It is more than probable that he was beginning to suspect the truth, that it was the mouth of a powerful river. The land of the north shore, moreover, was stony and barren and thoroughly forbidding. In his notes that night he wrote:

I did not see a cartload of good earth. To be short I believe that this was the land that God allotted to Cain.

A deeply religious man could think of nothing more damning to say than that. The land was inhabited in spite of its worthlessness. Cartier had come in contact with natives for the first time. They had followed him at a discreet distance in small and light craft which seemed to be made of the bark of trees. Cartier described them as “of indifferent good stature,” wearing their hair tied on the top “like a wreath of hay.”

At this stage Cartier showed himself the possessor in full measure of vision and daring. He set sail at once down the west of Newfoundland with the determination to locate the southern shore of this mighty river. Newfoundland was cloaked in a continuous fog which would lift occasionally and give awe-inspiring glimpses of high mountain peaks, stark and aloof and mysterious. It was self-evident to a pilot with a shrewd understanding of the movements of water that there must be a second outlet in the south. He was so sure of it that he did not waste any time in seeking it but turned his ships and with daring and imagination struck due west, thus coming in contact with the strong current of the gulf.

His reward came quickly. Sixty miles brought him to an island of such restfulness and beauty that he put into his notes, “One acre of this land is worth more than all the New Land,” meaning the shores which up to this time had constituted the whole of the new continent. Then he continued westward and passed the Magdalen group and the north shore of what would later be called Prince Edward Island, coming at last to what he was convinced must be the mainland.

It was wonderful country. The heat of July had covered the open glades with white and red roses. There were berries and currants in abundance and a wild wheat with ears shaped like barley. The trees were of many familiar kinds, white elm, ash, willow, cedar, and yew. To the north and west were high hills, but these were vastly different from the stern mountains of Newfoundland and the barrenness of the north shore. There was friendliness in their green-covered slopes and a welcome in their approach to the water’s edge.

Because of the heat, which was more intense than they were accustomed to in their own rugged Brittany, Cartier called the bay where they finally came to rest “Chaleur,” and the Bay of Chaleur it has been ever since.

It became apparent as soon as they made their first move to go ashore that eyes had been watching them. Canoes appeared suddenly on the water. They kept appearing until there were as many as fifty of them, filled with fearsome-looking savages who screeched and yelped with what seemed to be warlike intent. It needed no more than a glance to realize that they were different from the dark and somewhat stolid inhabitants of the north shore, who may have been of Eskimo stock. These were woodsmen, lithe and spare and strong. The Frenchmen did not like the look of things at all; and instead of making a landing as they had intended, they turned their boats about and began to row for the ships which were lying at anchor some distance away.

As soon as this happened the paddles of the Indians were dipped into the water with furious energy and the canoes came on in pursuit at a speed which astonished the white visitors. The boat in which Cartier was seated was surrounded in a matter of minutes. The natives were now seen to have faces painted hideously with red and white ocher so that they seemed to be wearing masks.

The commander had prepared for some such contingency and he signaled back to the ships. Watchers in the shrouds had been keeping their eyes open and had already sensed the danger. The tomkins had been stripped from two of the little cannon and the waddings of oakum, which were called fids, had been removed from the black muzzles. As soon as Cartier’s arm was raised the guns were fired.

To ears familiar with gunnery this was no more than a puff of smoke, but to the natives it was as though the voices of all the bad gods had spoken from afar. They took to their paddles in such haste that in a matter of seconds they were plowing paths of retreat in all directions. The white men sighed gustily with relief and leaned to their oars in a desire to attain the safety of the ships.

The Indians were of stouter heart than their panicky retreat would seem to suggest. Finding that no harm had come to them from the horrendous uproar of the guns, they brought their canoes about and began a second approach, this time in a wide and cautious circle. Cartier decided to take no further chances and, before the canoes had come close again, he had his men raise their muskets and fire a volley in the air. This was too much for the redskins. The voice of the distant cannon had been deep and resounding, but the rattle of musketry was sharp and staccato and it shattered the air about their ears with a threat of immediate violence. They made a second retreat, and after that, as Cartier noted in his journal, “would no more follow us.”

The next day the savages recovered from their panic and came back with an obvious desire to trade, although they were careful to come well equipped with the stone hatchets they called cochy and their knives, which they called bacan. There were hundreds of them, including many women and children. They had brought cooked meats with them which they broke into small pieces and placed on squares of wood; and then withdrew to see if their offerings would be accepted. Cartier’s men tasted the meat and found it a welcome change from the fish and salted fare on which they had been living. When the natives saw that their gift had been well received, they danced exuberantly and threw salt water on their heads and shouted, “Napou tou daman asurtat!” with the best good will. The women were less fearful than the men and certainly more curious, for they came up close to these godlike visitors who had, seemingly, dropped from the clouds. They ran their hands over the wondrous costumes, uttering loud cries of astonishment and delight.

The result was that the two groups, the fair-skinned newcomers, garbed in which seemed to be all the hues of the rainbow, and the almost naked redskins, soon got together for a trading spree. It followed the usual course of all such exchanges. The natives parted with valuable furs and received trinkets in exchange—bracelets made of tin and the simplest of iron tools and “a red hat for their captain”—but were certain that they were having all the best of it and went away happy.

The ships turned north again on July 12 and came to another deep bay which Cartier hoped at first would prove to be the passage through which this great volume of water came rolling down to the sea. Finding that he was wrong, but becoming convinced that he had found the mainland, he had his men construct a tall cross of wood. It proved to be an impressive monument, thirty feet high, with a shield nailed to the crossbeam on which the fleur-de-lis had been carved. At the top, in large Gothic characters, the words had been inscribed:

Vive le roy de France

The cross was erected on the shore with great ceremony in the presence of a large gathering of natives who had emerged from the woods or had paddled across the water in their fleet canoes. As soon as it had been securely fixed, the white men dropped to their knees and raised their arms toward the heavens in a gesture of humility and praise.

This was a memorable occasion. To all with an eye for the picturesque and a desire to see the story of the past dressed out in full panoply, it has seemed the real starting point of Canadian history. The exact spot where the cross was raised has never been ascertained. The tall beam with its antique carving soon began to sag from the buffeting of the winds and finally dropped and in time merged with the soil; but the memory of that impressive moment when it was first elevated against the background of green verdure and blue sky will remain forever in Canadian minds.

The watching natives had some of the imaginative quality which would be displayed so often later. They stood in silent ranks, their dark eyes fixed on the symbol of a strange faith. Instinctively they knew that these thickset men in multicolored clothes were claiming the land for themselves. Storms had been raging and so it is possible that the sun was not out; but the apprehensive savages did not need to see the shadow of the cross stretching out over this fair domain to know that their possession was being threatened. They looked at their chief, a very old man who had wrapped his skinny shoulders in a ceremonial blanket. He had turned his gaze up to the skies as though seeking guidance from the gods who dwelt there. As he made no move, his followers began to shout that shrill demand which would be heard so many times later and in so many ways, sometimes expressed in the blood lust of the war cry, the “Cassee kouee!” of the dreaded Iroquois; and always having the same meaning, “Go away! Go away!”

When the ceremony had been completed, the mariners returned to their ships. The Indians followed later in their canoes, and the old chief, standing up in one of them, delivered a long oration. The nature of his talk could be determined from the gravity of his manner and the expressive gestures he used. He was telling the fair-skinned visitors that this land belonged to his people and that they had no intention of sharing it.

Cartier invited the old man and his followers to come aboard the ships. They were feasted and given presents and made much of generally. Two of the chiefs sons were given red cloaks and hats, which they donned with childlike eagerness. In the meantime the French leader had succeeded by the use of gestures in convincing the solemn old orator that the cross was intended only as a guidepost. Then with more gestures he invited the two sons to stay and sail back to the land from which the magic ships had come. They assented without any hesitation.

The status of divinity which the deluded natives were always so willing to grant the newcomers was due to many things but above everything else to the wonder of the white man’s sails. This was a phenomenon which never failed to entrance them; the breaking out of those great squares of color and then the graceful speed with which the monster vessels swayed and dipped with the winds and so faded off into the horizon.

Not more than half convinced of the honesty of the white men, the savages were still entranced by the wonder of the sails as they watched the departure of these strange gods. Cartier, it may be taken for granted, observed everything carefully from his post on the quarter-deck: the activities on deck and the strutting figures of the clownish sons of the old chief, the doubt in the slow dip of the native paddles. He was glad to be away.

The land receded slowly and the tall cross faded back into the black and green of the trees. Filled with the purpose which had brought him here, Cartier could not have doubted that on this momentous day, on this shore to which he had given the name of Gaspé, he had founded an empire for France.

3

Cartier struck north again and came to a very large island which would be known later as Anticosti. The ships passed to the north of this island and reached the west point with great difficulty. The current here was strong and fierce and an August storm was raging. The final stage of the northern passage was attempted in one of the boats while the ships rode uneasily at anchor. The attempt failed. Thirteen men, pulling furiously against the current, were unable to advance more than a very few feet in an effort which lasted for hours. Accordingly Cartier had himself put ashore and went on foot to the westernmost tip of the island. Here he stood for a considerable time, looking full ahead into that great surging mass of water. The distance from Gaspé to Anticosti had proven that the passage had narrowed appreciably. It must have been clear to him by this time that he was in the mouth of a mighty and majestic river.

Returning to his ship, he summoned all the men of the two crews to a council. In his mind there must have been a consciousness that new concepts of democracy would be developed in this land; at any rate, his notes say that he called in “the sailing-masters, pilots and sailors.” They came and stood closely packed about him or on the open deck below, the sailors no doubt in the rear, saying nothing and holding their flat caps in their hands with due respect. The commander outlined the decision which they faced, making it clear first that in his belief they were on the threshold of discovery, that the furiously flowing water against which they had been battling came straight from the heart of this new continent. Conditions made it impossible, however, for them to progress any farther that year. Should they set up winter quarters and be prepared to resume their explorations in the spring, or should they begin at once their return to St. Malo?